Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Raised intracranial pressure (ICP) has been proposed as an isolated cause of retinal hemorrhages (RHs) in children with suspected traumatic head injury. We examined the incidence and patterns of RHs associated with increased ICP in children without trauma, measured by lumbar puncture (LP).

METHODS:

Children undergoing LP as part of their routine clinical care were studied prospectively at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and retrospectively at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Inclusion criteria were absence of trauma, LP opening pressure (OP) ≥20 cm of water (cm H2O), and a dilated fundus examination by an ophthalmologist or neuro-ophthalmologist.

RESULTS:

One hundred children were studied (mean age: 12 years; range: 3–17 years). Mean OP was 35 cm H2O (range: 20–56 cm H2O); 68 (68%) children had OP >28 cm H2O. The most frequent etiology was idiopathic intracranial hypertension (70%). Seventy-four children had papilledema. Sixteen children had RH: 8 had superficial intraretinal peripapillary RH adjacent to a swollen optic disc, and 8 had only splinter hemorrhages directly on a swollen disc. All had significantly elevated OP (mean: 42 cm H2O).

CONCLUSIONS:

Only a small proportion of children with nontraumatic elevated ICP have RHs. When present, RHs are associated with markedly elevated OP, intraretinal, and invariably located adjacent to a swollen optic disc. This peripapillary pattern is distinct from the multilayered, widespread pattern of RH in abusive head trauma. When RHs are numerous, multilayered, or not near a swollen optic disc (eg, elsewhere in the posterior pole or in the retinal periphery), increased ICP alone is unlikely to be the cause.

Keywords: intracranial pressure, papilledema, retinal hemorrhage

What’s Known on This Subject:

Retinal hemorrhage (RH) is an important sign of pediatric abusive head trauma. Raised intracranial pressure (ICP) is sometimes proposed as an alternate cause of RH in children being evaluated for possible child abuse.

What This Study Adds:

Nontraumatic, markedly elevated ICP rarely causes RH in children. When it does, RH are superficial intraretinal and located adjacent to a swollen optic nerve head. This pattern does not match the widespread pattern seen in abusive head trauma.

Retinal hemorrhages (RHs) are an important sign of pediatric abusive head trauma (AHT), present in an estimated 85% of cases.1–9 A range of RH findings may be present, with increasing severity of RHs being associated with an increasing specificity for AHT.1,10,11 This range includes no RH; a few intraretinal hemorrhages confined to the posterior pole of the eye; multilayered, too-numerous-to-count RHs extending into the retinal periphery; and hemorrhagic macular retinoschisis (splitting of the retinal layers) with or without retinal folds. Vitreoretinal traction injury to the retinal vessels caused by repetitive deceleration injury is the leading and most-supported hypothesized mechanism underlying these findings, based on clinical, autopsy, laboratory, and finite element modeling evidence.1,12 Additional proposed mechanisms have included venous occlusion from raised intrathoracic or intracranial pressure (ICP) and tracking of intracranial blood along the optic nerves.1

Increased ICP has been proposed as an isolated cause of RH in children with suspected traumatic head injury.1,13 Because ICP may be elevated in children being evaluated for AHT, understanding the association between increased ICP and RHs, and more specifically the RH patterns observed with raised ICP, is important because the diagnostic specificity of RHs for trauma may be altered. The extensive clinical experience of pediatric ophthalmologists suggests that isolated raised ICP rarely causes RH, and that RH due to raised ICP is limited to the peripapillary RHs sometimes seen with papilledema.13 However, there are limited published data describing RH findings associated with raised ICP in children.

The goal of the current study was to determine the incidence and patterns of RH associated with increased ICP in children, as measured by using lumbar puncture (LP).

Methods

This 2-center cohort study was conducted at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. Data were collected as part of a prospective study of children undergoing LP during their routine clinical care in Philadelphia between January 2007 and February 200914; the data were collected retrospectively in Columbus. In both centers, subjects were enrolled consecutively. Subjects in Columbus were identified from a clinical database of all patients seen in an outpatient ophthalmology clinic, using a diagnosis search of headache, intracranial hypertension, papilledema, or RHs, between January 2009 and December 2011; nearly all of these patients were seen as an emergency department consultation or urgent outpatient visit. Portions of data unrelated to RH from a previously published study of children with optic nerve head swelling were included in the current analysis because these children were enrolled in the prospective study.15 These data included medical history and opening pressure (OP) on LP.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both institutions and was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects for inclusion in the prospective study and was waived for the retrospective review. All ophthalmologic examinations were performed as part of routine clinical care and did not require separate informed consent.

Subjects were children between 1 and 17 years of age undergoing an LP with OP, as part of routine clinical care. Children were excluded if they had head trauma, an indwelling ventricular shunt or lumbar drain (because the active drainage of cerebrospinal fluid from a shunt or drain would reduce the OP), a brain tumor, active cancer treatment, or medical instability such that the additional time required to obtain OP would compromise patient safety. At both centers, the LP was performed in the lateral recumbent position, with or without sufficient sedation to ensure no agitation.

OP was measured with a standard manometer and defined as the highest resting level sustained for 10 seconds. Despite 2 pediatric studies suggesting a normal OP in children can be as high as 28 cm of water (cm H2O),14,16 we defined thresholds for an elevated OP as both 20 cm H2O and 28 cm H2O to avoid potentially excluding children with a mildly elevated OP. In both centers, when the OP was beyond the length of the manometer, the clinician recorded a “greater than” reading. In Philadelphia, an OP higher than 55 cm H2O was recorded as “OP >55 cm H2O.” In Columbus, early in the study period, the manometer used was only 35 cm tall, while later in the study period, the manometer was 55 cm tall. Therefore, there was variability in terms of the OP level for which the clinician recorded only a “greater than” reading (>35 cm early in the study period, >55 cm later in the study period). For the purposes of calculating descriptive statistics for this study, for data from both institutions, the OP was considered to be equal to 1 cm higher than the “greater than” level recorded by the clinician (eg, an OP >55 cm H2O was considered to be equal to 56 cm H2O). The etiology of elevated OP was categorized as demyelinating disease, rheumatologic disease, infectious disease, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, or other.

All children underwent a dilated fundus examination with indirect ophthalmoscopy performed by a pediatric ophthalmologist or neuro-ophthalmologist, completed in most cases within 24 to 48 hours of the LP but with a maximum limit set at 96 hours. The types, locations, and number of RHs and the presence of disc swelling or other fundus findings were recorded.

Results

One hundred children met inclusion criteria, 44 in Philadelphia and 56 in Columbus. The mean age was 12 years (range: 3–17 years). The mean ± SD OP was 35 ± 6.4 cm H2O (range: 20–56 cm H2O). Thirty-two children had an OP of 20 to 28 cm H2O, and 68 children had an OP >28 cm H2O. Overall, 88% of children had symptoms of raised ICP, including nausea, vomiting, headache, back pain, lethargy, or diplopia. The etiology of elevated OP was most commonly idiopathic intracranial hypertension (n = 70 children [70%]) but also included infectious (n = 6), rheumatologic (n = 3), or demyelinating disease (n = 4), dural venous sinus thrombosis (n = 6), and “other” in 11 children. Of the 11 children classified as other, 1 child had Guillain-Barré syndrome, and 10 children had an unknown etiology. Aside from those subjects with venous sinus thrombosis, none of the children had identified coagulation or clotting abnormalities.

Ninety-three percent of fundus examinations were completed within 48 hours of the LP. Optic disc swelling was present in 74 (74%) children. Among children with an OP 20 to 28 cm H2O, 18 (56%) had disc swelling; among children with an OP >28 cm H2O, 56 (82%) had disc swelling. Sixteen (16%) children were found to have splinter optic disc hemorrhages or peripapillary nerve fiber layer (superficial intraretinal) hemorrhages. All 16 children with RHs had optic disc swelling described as moderate to severe. Eight of the 16 children had only splinter hemorrhages directly on the optic disc; their mean OP was 40 cm H2O. The remaining 8 children also had superficial intraretinal hemorrhages located adjacent to a floridly swollen optic disc (Fig 1). All 8 children had markedly elevated OP (mean: 44 cm H2O). Four children had associated cotton wool spots and lipid exudates. No children had RH in the central or temporal macula, along the retinal vascular arcades distal to the peripapillary region, or in the retinal periphery, nor did any children have preretinal or subretinal hemorrhages, retinoschisis, or macular folds. The etiology of elevated OP in the children with RHs was idiopathic intracranial hypertension in 15 children and Guillian-Barré syndrome in 1 child. None of the 6 children with dural sinus venous thrombosis had RHs.

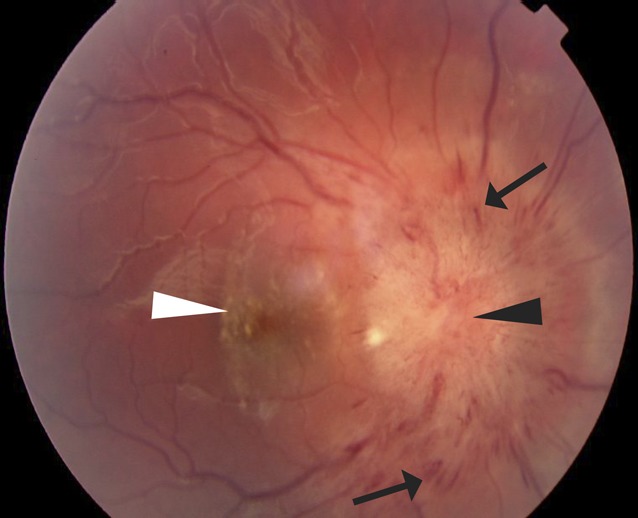

FIGURE 1.

Fundus photograph of the right eye of a child with papilledema and vision loss severe enough to require optic nerve sheath fenestration. There are nerve fiber layer intraretinal hemorrhages (arrows) on and near a floridly swollen optic nerve head (black arrow head) and lipid exudates (white arrow head) in the central macula. The OP was >56 cm H2O on initial LP.

Discussion

We found that a small proportion of children with elevated OP on LP had RHs, which were uniformly associated with florid papilledema and were limited to peripapillary superficial nerve fiber layer intraretinal hemorrhages. These findings are consistent with the anecdotal but extensive experience of ophthalmologists who have examined children with increased ICP over decades.17–19

The RHs observed in association with raised ICP were not consistent with the severe hemorrhagic retinopathy seen in many victims of AHT (Fig 2). Even when children had severe papilledema and markedly elevated OP, the RHs were neither widespread nor numerous, were not present in the peripheral retina, and did not even extend throughout the posterior pole of the fundus. Instead, the RHs were limited to the peripapillary (perioptic nerve head) region. The types of hemorrhage were limited to optic disc and intraretinal hemorrhage, in contrast to the multilayered RHs often seen in children with AHT. Finally, splitting of the retinal layers (retinoschisis) and perimacular retinal folds were not observed in the study, even in a case of papilledema causing vision loss severe enough to warrant optic nerve sheath fenestration (Fig 1).

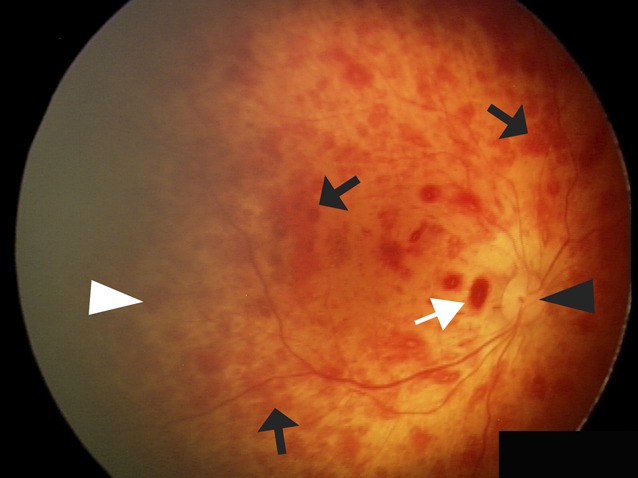

FIGURE 2.

Comparative fundus photograph of the right eye of a child with AHT not enrolled in the current study. The optic disc appears healthy without swelling (black arrowhead). There are too-numerous-to-count diffuse intraretinal blot hemorrhages (black arrows) throughout the posterior pole and extending into the retinal periphery (white arrowhead). There are also a few small preretinal hemorrhages (white arrow).

There are also differences between some of the milder RH patterns that can be seen with accidental or AHT and the RHs observed in this study. The intraretinal hemorrhages in children with raised ICP were superficial, nerve fiber layer hemorrhages, whereas children with head trauma commonly also have deeper, dot-and-blot intraretinal hemorrhages (Fig 2).1 In addition, all of the study children with RHs had severe papilledema, but disc swelling is an uncommon finding in children with AHT, present in <9% of cases.8,20

Although intracranial monitoring is considered the gold standard for measuring ICP, it carries a significant risk of intracranial hemorrhage and infection, and is therefore typically reserved for cases of malignant ICP requiring acute medical or surgical intervention. Most children’s ICP is indirectly measured by using the OP measure during an LP. Historically, an abnormal OP in children was believed to be ≥20 cm H2O, although standardized prospective studies had not been performed.21 Recently, 1 prospective14 and 1 retrospective16 pediatric study demonstrated that children without other evidence of elevated ICP can have OP as high as 28 cm H2O, suggesting that an OP >20 cm H2O may not necessarily be abnormal. We chose to include children who met the traditional threshold for elevated OP (≥20 cm H2O) to avoid excluding children who may have had a mildly elevated OP. However, none of the children with an OP 20 to 28 cm H2O had RH, and even among children with OP >28 cm H2O, RHs were limited to the peripapillary superficial RH pattern seen in a minority of children.

Strengths of our study include a relatively large cohort of children with elevated OP, prospective data collection in the Philadelphia cohort, and dilated fundus examinations performed by pediatric ophthalmologists and neuro-ophthalmologists with expertise in examining children with optic nerve abnormalities and RH. In addition, enrollment rates at the centers were very high. In Columbus, all eligible patients were included retrospectively. In Philadelphia, 96% of eligible children were enrolled in the prospective LP study.14 A number of limitations need to be considered as well. The children in the study were older than children who usually suffer AHT. However, infants have open cranial sutures and fontanelles and are therefore thought to be less likely to develop papilledema22 and therefore associated RH. The exact duration of elevated ICP could not be determined in our study population, although symptoms ranged from days to months, and most patients at both centers presented with acute or subacute onset of symptoms. Not knowing precisely the cases in which the rise in ICP was acute or chronic limits our ability to hypothesize how the mechanism of RHs differs between AHT and the subjects in our study with isolated, nontraumatic elevated ICP. Of note, the hemorrhage pattern observed in Terson syndrome, which is thought to arise from a sudden increase in ICP due to intracranial hemorrhage, is primarily that of preretinal and vitreous hemorrhage and rarely resembles the patterns of hemorrhage seen in AHT.23–27 The exclusion of patients too unstable to allow time for OP to be measured might bias the prevalence estimate of RH downward if sicker patients are assumed to be more likely to have RH, but the validity of this assumption is not clear, and there is no reason to suspect that the RH patterns associated with elevated ICP would differ in such children. Finally, in a small minority of cases, the eye examination preceded or followed the LP by up to 96 hours, a time period during which intraretinal hemorrhages might begin to resolve. However, 93% of examinations occurred within 48 hours, and preretinal and subretinal hemorrhage take weeks to resolve and would still have been present.

Conclusions

Isolated nontraumatic increased ICP, as measured according to OP, uncommonly causes RH in children. When RHs are present, they are associated with markedly elevated ICP and appear as superficial, intraretinal hemorrhages, invariably located adjacent to a swollen optic nerve head. Disc hemorrhages may appear on the swollen nerve head itself as well. When RHs are numerous, widespread in extent, multilayered, or not near a swollen optic disc, such as in the periphery or elsewhere in the posterior pole, increased ICP alone is unlikely to be the cause, and alternative causes, including trauma, should be considered.

Glossary

- AHT

abusive head trauma

- ICP

intracranial pressure

- OP

opening pressure

- RH

retinal hemorrhage

Footnotes

Dr Binenbaum conceptualized and designed the overall study, collected data at 1 center, collated data from both centers, performed the initial analysis, co-wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and made editing decisions for the final draft of the manuscript; Dr Rogers conceptualized and designed the study at 1 center (retrospective portion), collected data at 1 center, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Forbes contributed to the design of the overall study, assisted with interpretation of the data, co-wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Levin contributed to the design of the study, assisted with interpretation of the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Clark collected data at 1 center and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Christian contributed to the design of the overall study, assisted with interpretation of the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Liu contributed to the design of the study at 1 center (the prospective portion), assisted with interpretation of the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Avery conceptualized and designed a portion of the study at 1 center (the prospective portion), assisted with interpretation of the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Dr Levin has consulted as an expert witness for both the defense and the prosecution in cases related to child abuse; Dr Liu has consulted for Ipsen Pharmaceuticals regarding elevated intracranial pressure arising from the use of recombinant human insulin-like growth factor; Dr Christian provides medical-legal expert work in child abuse cases; and the other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by National Institutes of Health grants (K12 EY-015398 [Dr Binenbaum] and 1T32NS061779-01 [Dr Avery]) and its Loan Repayment Program (Dr Binenbaum, Dr Avery). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Levin AV. Retinal hemorrhage in abusive head trauma. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):961–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman RL, Kutscher ML, Brand DA. The “shaken-baby syndrome.” N Engl J Med. 1998;339(18):1329–1330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duhaime AC, Christian CW, Rorke LB, Zimmerman RA. Nonaccidental head injury in infants—the “shaken-baby syndrome.” N Engl J Med. 1998;338(25):1822–1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green MA, Lieberman G, Milroy CM, Parsons MA. Ocular and cerebral trauma in non-accidental injury in infancy: underlying mechanisms and implications for paediatric practice. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80(4):282–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harcourt B, Hopkins D. Ophthalmic manifestations of the battered-baby syndrome. BMJ. 1971;3(5771):398–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kivlin JD. Manifestations of the shaken baby syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12(3):158–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levin AV. Ocular manifestations of child abuse. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1990;3:249–264 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morad Y, Kim YM, Armstrong DC, Huyer D, Mian M, Levin AV. Correlation between retinal abnormalities and intracranial abnormalities in the shaken baby syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134(3):354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao N, Smith RE, Choi JH, Xu XH, Kornblum RN. Autopsy findings in the eyes of fourteen fatally abused children. Forensic Sci Int. 1988;39(3):293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhardwaj G, Chowdhury V, Jacobs MB, Moran KT, Martin FJ, Coroneo MT. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of ocular signs in pediatric abusive head trauma. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(5):983–992.e17 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Binenbaum G, Mirza-George N, Christian CW, Forbes BJ. Odds of abuse associated with retinal hemorrhages in children suspected of child abuse. J AAPOS. 2009;13(3):268–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coats B, Binenbaum G, Peiffer RL, Forbes BJ, Margulies SS. Ocular hemorrhages in neonatal porcine eyes from single, rapid rotational events. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(9):4792–4797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiau T, Levin AV. Retinal hemorrhages in children: the role of intracranial pressure. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(7):623–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avery RA, Shah SS, Licht DJ, et al. Reference range for cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure in children. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(9):891–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avery RA, Licht DJ, Shah SS, et al. CSF opening pressure in children with optic nerve head edema. Neurology. 2011;76(19):1658–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee MW, Vedanarayanan VV. Cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure in children: experience in a controlled setting. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;45(4):238–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzekov C, Cherninkova S, Gudeva T. Neuroophthalmological symptoms in children treated for internal hydrocephalus. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1991–1992;17(6):317–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nazir S, O’Brien M, Qureshi NH, Slape L, Green TJ, Phillips PH. Sensitivity of papilledema as a sign of shunt failure in children. J AAPOS. 2009;13(1):63–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinchon M, Delestret I, DeFoort-Dhellemmes S, Desurmont M, Noulé N. Subdural hematoma in infants: can it occur spontaneously? Data from a prospective series and critical review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26(9):1195–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kivlin JD, Simons KB, Lazoritz S, Ruttum MS. Shaken baby syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(7):1246–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rangwala LM, Liu GT. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(6):597–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen ED, Byrd SE, Darling CF, Tomita T, Wilczynski MA. The clinical and radiological evaluation of primary brain tumors in children, part I: clinical evaluation. J Natl Med Assoc. 1993;85(6):445–451 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutierrez Diaz A, Jimenez Carmena J, Ruano Martin F, Diaz Lopez P, Muñoz Casado MJ. Intraocular hemorrhage in sudden increased intracranial pressure (Terson syndrome). Ophthalmologica. 1979;179(3):173–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schultz PN, Sobol WM, Weingeist TA. Long-term visual outcome in Terson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(12):1814–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhn F, Morris R, Witherspoon CD, Mester V. Terson syndrome. Results of vitrectomy and the significance of vitreous hemorrhage in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(3):472–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogawa T, Kitaoka T, Dake Y, Amemiya T. Terson syndrome: a case report suggesting the mechanism of vitreous hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(9):1654–1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhardwaj G, Jacobs MB, Moran KT, Tan K. Terson syndrome with ipsilateral severe hemorrhagic retinopathy in a 7-month-old child. J AAPOS. 2010;14(5):441–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]