Abstract

Positive association between cardiovascular diseases and osteoporosis is important because it concerns two major public health problems. Men and women with cardiovascular diseases (including severe abdominal aortic calcification (AAC) and peripheral arterial disease) tend to have lower areal and volumetric bone mineral density (BMD) as well as faster bone loss, although findings vary according to skeletal site. On one hand, severe forms of cardiovascular diseases (heart failure, myocardial infarction, hypertension, severe AAC) are associated with higher risk of osteoporotic fracture, especially hip fracture. This link was found in the studies based on healthcare databases and the cohort studies. On the other hand, low BMD, history of fragility fracture, vitamin D deficit and increased bone resorption are associated with higher risk of major cardiovascular events (myocardial infraction, stroke, cardiovascular mortality). Moreover, osteocalcin secreted by osteoblasts may be involved in the regulation of energetic and cardiovascular metabolism. The association between both pathologies depends partially on the shared risk factors, and also on the mechanisms that are involved in the regulation of bone and cardiovascular metabolism. Interpretation of the data should take into account methodological limitations: representativeness of the cohorts, quality of the registers and the information obtained from questionnaires, severity of diseases, number of events (statistical power) and their temporal closeness, availability of the information on potential confounders. It seems that patients with severe form of osteoporosis would benefit from assessment of the cardiovascular status and vice versa. However, official guidelines for the clinical practice are still lacking.

Many studies published over the past 20 years show a significant positive association between cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and osteoporosis. This association is important because it concerns two major public health problems. The investigation of shared biomarkers (clinical, radiological, biochemical) may improve identification of subjects at high risk of both diseases. The investigation of shared pathophysiological mechanisms may help to understand the pathophysiology of these diseases and to establish new treatments that could be efficient in both diseases. Below, I have tried to analyze various groups of clinical studies to better understand the association between osteoporosis and CVD as well as discrepancies between the studies. My review is focused on the epidemiological studies of the general population, and I have not analyzed the association between bone and CVD in chronic renal failure.

Association between cardiovascular diseases and bone mineral density

Several studies showed that CVD and arterial calcification are associated with decreased bone mineral density (BMD), although findings vary according to skeletal site and gender. Severe abdominal aortic calcification (AAC) was associated with lower BMD at the spine and hip in older women,1 at the hip and whole body (but not spine) in older women (but not men),2 at the lumbar spine (but not femoral neck) in a cohort of men and women,3 at the femoral neck in women4 and at whole body and distal forearm (but not at the spine or hip) in older men.5 Severe AAC was associated with lower trabecular volumetric BMD at the spine in postmenopausal women,6 in peri- and postmenopausal black and white women,7 and in men and women aged ⩾45 years.8 In a group of siblings concordant for type 2 diabetes, severity of the coronary and aortic calcification was correlated negatively with spine volumetric BMD.9 In other studies, the association between AAC severity and BMD was weak or non-significant.10,11,12,13

Limited data also suggest a weak but significant association between severe peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and lower BMD at the hip.14,15,16 Elevated diastolic (but not systolic) blood pressure was associated with lower BMD at the total body, trochanter and Ward's triangle in a small group of 47 men aged 24 to 77 years.17

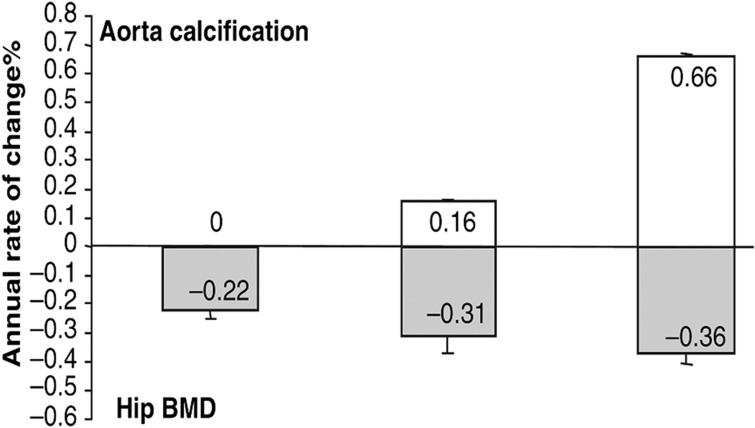

CVD were also associated with the accelerated bone loss. Faster progression of AAC was associated with faster bone loss at the hip in older women,1 at the lumbar spine (but not femoral neck),3 at the spine in postmenopausal women,7 at the metacarpal in women followed up across the menopause,18 and at the metacarpal in women, but not men19 (Figure 1). Hypertension was associated with faster bone loss in elderly white women.20 Moreover, in the MrOS cohort, the elderly men with PAD had faster bone loss at the total hip and its components.21

Figure 1. Annualized rate of change (%) in total hip bone mineral density (grey bars) according to the tertiles of change in the abdominal aortic calcification score (white bars) in 2662 older women from the PERF study followed up prospectively for 7.5 years on average.

Bars show mean±s.e.m. P-value for trend=0.019 after adjustment for age and baseline BMD. Reproduced from Bagger et al.1 with permission from Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Thus, the cross-sectional studies show an association between CVD and BMD. The observed differences between the studies may be related to the various populations, age range, sex, skeletal site and method of BMD measurement. The associations of lumbar spine BMD, measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry, with AAC are weak and not reliable because of the frequent arthritis in the elderly. The associations are similar for the predominantly cortical and predominantly trabecular skeletal sites. The difference in BMD is greater for subjects with more severe CVD or severe AAC. Adjustment for confounders may influence the results. In particular, adjustment for the shared risk factors of both diseases (for example, smoking, sedentary lifestyle) may falsely attenuate the existing relationship. The association between CVD and bone loss is stronger in women, probably because in postmenopausal women bone loss is faster than in older men. Therefore, estimation of bone loss may be more accurate in women than in men (because the effect of the measurement error is smaller). Lower BMD and faster bone loss at the lower limbs in patients with the PAD suggest that the local effect related to the decreased blood flow may also contribute to this association.

Association between the prevalent cardiovascular pathology and incident fracture

Epidemiological studies on the association between CVD and fractures can be divided into two groups. The first group is based on the healthcare databases and large epidemiological studies, which were not specifically designed to study osteoporosis. These studies show that severe forms of CVD are associated with higher risk of fragility fracture.

In the Swedish Twin Registry, individuals with heart failure, ischemic heart disease or PAD had significantly, two- to fourfold higher risk of hip fracture.22 In a study that was a part of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, myocardial infarction was associated with higher risk of all types of osteoporotic fracture.23 In a large Danish study carried out in about 500 000 individuals using the data from the National Health Service, a trial fibrillation was associated with higher risk of the fracture of hip, distal forearm or spine during the first 3 years after the incident.24 In addition, patients with myocardial infarction had higher risk of hip fracture (but not spine or forearm fracture), during first 3 years. Finally, elderly patients with heart failure and patients with other cardiovascular diagnoses were identified in the healthcare databases of the province Alberta, Canada.25 The controls with CVD were selected because they can share some cardiovascular risk factors and potentially be eligible for similar medications. Patients with heart failure had a fourfold higher risk of sustaining any fracture requiring hospitalization compared with other cardiovascular diagnoses.

The advantage of the population-based studies is the large representative cohort, large number of individuals with different forms of CVD, in particular, large number of subjects with severe forms of CVD and large number of fractures. Follow-up data are available instantly and the investigated group is not influenced by participation bias, which is quite frequent in the cohort studies.

However, these studies also have limitations. The quality of the data depends on the quality and the exhaustiveness of the register and on the completeness of the follow-up. There is no formal ascertainment of the investigated diseases, both false positives and false negatives are possible. The use of the same diagnostic criteria for a given disease is not guaranteed; they change with time over long follow-ups and may vary according to the physician or hospital. Such studies capture better hip fractures (almost all hospitalized) than other peripheral fractures (often treated on the outpatient basis). In many studies, the low number of investigated covariates may have a confounding role in a study of fracture, especially BMD, circumstances of the fracture, prevalent fractures, prevalent falls or use of vitamin D and calcium, which may be available without prescription. Similar to other long-term prospective studies, these studies cannot account for changes in medications during the follow-up. It is a limitation in case of the study on fractures, because some medications may induce bone loss or increase the risk of falling.

The second group comprises epidemiological studies focused on osteoporosis or CVD. Most of them show that CVD are associated with a higher risk of fragility fracture. In a cohort of home-dwelling men and women followed up prospectively for 11.5 years, incident heart failure conferred higher subsequent risk of hip fracture26. After adjustment for confounders, the relative risk slightly attenuated and marginally lost statistical significance. Thus, the association between heart failure and hip fracture may be partly explained by shared risk factors. However, BMD was not measured. Interestingly, in a cohort of 45 509 subjects followed up for up to 10 years, recently diagnosed heart failure remained significantly associated with a higher risk of fragility fracture after adjustment for confounders including baseline BMD at the spine or hip.27

In a cohort of older Caucasian women (SOF study) followed up prospectively for 3.5 years, higher resting heart rate was associated with a progressive increase in the risk of fragility fracture (vertebra, hip, pelvis, rib) after adjustment for confounders.28 Heart failure and rapid heart rate may reflect poor health status and/or frailty. However, the adjustment for the measures of general health and frailty had a limited impact on these associations.

Some,1,4,5 but not all,2,29,30 prospective studies showed that severe AAC is associated with higher risk of fragility fracture. This association was found both in men and in women, for various types of fracture (hip, vertebra, all osteoporotic fractures) and remained significant after adjustment for BMD. However, the increased fracture risk was found mainly in the individuals with severe AAC, but not in the subjects with mild (limited) AAC. In addition, the results of the analyses are influenced by the higher mortality in the subjects with severe AAC and by the duration of the follow-up. Similar positive association between the presence of fragility fracture and calcifications in the abdominal aorta or carotid artery was also found in the cross-sectional studies.6,31,32

In the elderly men (MrOS cohort), PAD was associated with higher risk of peripheral fracture.21 The association lost marginally the significance after adjustment for hip BMD and falls, which indicates that it may partly depend on the lower BMD and higher risk of fall in men with impaired blood flow in the lower limbs. By contrast, in the Rancho Bernardo Study, PAD was not associated with the fracture risk in men or in women.33 However, the number of individuals followed up prospectively and the number of incident fractures were relatively low, most of the subjects had mild form of PAD and the individuals with PAD were less likely to return for the follow-up visit.

Finally, studies using large administrative registers showed that hypertension is associated with a higher risk of fracture (especially during the first 3 years after diagnosis).22,24 By contrast, such association was not found in a study based on self-reported data on hypertension obtained using self-administered questionnaires.34

Sennerby et al.35 compared postmenopausal women having sustained a hip fracture with controls from the same region. The information on the cases and the controls was based on questionnaire and hospital records. Heart failure, cerebrovascular lesion and hypertension were associated with higher risk of hip fracture. More importantly, the risk of hip fracture increased progressively with the number of hospitalizations for CVD before the study and was highest during the first 6 months after hospitalization.

Jointly, these studies show that various types of CVD are associated with higher risk of fracture. These studies allow us to assess this association in a well-characterized cohort and to include in the statistical models a large number of confounding factors. In such cohorts, it is possible to use standardized methods to assess and to ascertain the investigated variables. However, participation bias may limit representativeness of the cohort. In particular, the elderly with severe diseases often decline to participate in epidemiological follow-ups. In addition, such studies necessitate long follow-ups. This relationship holds mainly for severe CVD and for major osteoporotic fractures (especially hip fracture). It remains significant after adjustment for BMD, which indicates the existence of shared mechanisms underlying both diseases, which are not explained by BMD. This association attenuates after adjustment for shared risk factors, which indicates that it depends partially on the risk factors that are common for both diseases. The relationship between prevalent CVD and fracture incidence has been studied more thoroughly in women than in men. In addition, it seems to be more significant in women; however, the incidence of fragility fractures in men is lower, which results in poorer statistical power.

Association between the prevalent bone abnormality and incident CVD

Similarly, a substantial number of studies have assessed for the past 20 years the risk of CVD in patients with low BMD, fragility fractures, vitamin D deficit and abnormalities of bone turnover. In a cohort of American elderly women, low calcaneus BMD was associated with higher risk of stroke during a 2-year follow-up.36 Similarly, in a cohort of Swedish elderly men and women, low femoral neck BMD was associated with higher risk of stroke during a follow-up of 5.5 years.37

In the placebo branch of the MORE study, osteoporosis (T-score <−2.5 at the spine or the femoral neck) was associated with a fivefold higher risk of cardiovascular event (for example, stroke, myocardial infarction).38 In a group of 6800 men and women (MONICA and Västerbotten Intervention Programme databases), low hip BMD was associated with higher risk of myocardial infarction.39 In men, this association remained significant after adjustment for confounders including cardiovascular risk factors. In the Framingham cohort, lower cortical mass of the second metacarpal was associated with a higher incidence of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women but not in older men.40 In the Health ABC cohort, incident CVD was defined as the onset of coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, PAD or carotid artery disease.41 In this cohort, low hip BMD was associated with higher incidence of the above CVD in black, but not white, women. Moreover, low lumbar spine volumetric BMD was associated with higher CVD incidence in white, but not black, men.

Finally, in postmenopausal Danish women recruited for various clinical studies, low bone mass was also associated with higher cardiovascular mortality after adjustment for confounders, including age and cardiovascular risk factors.42

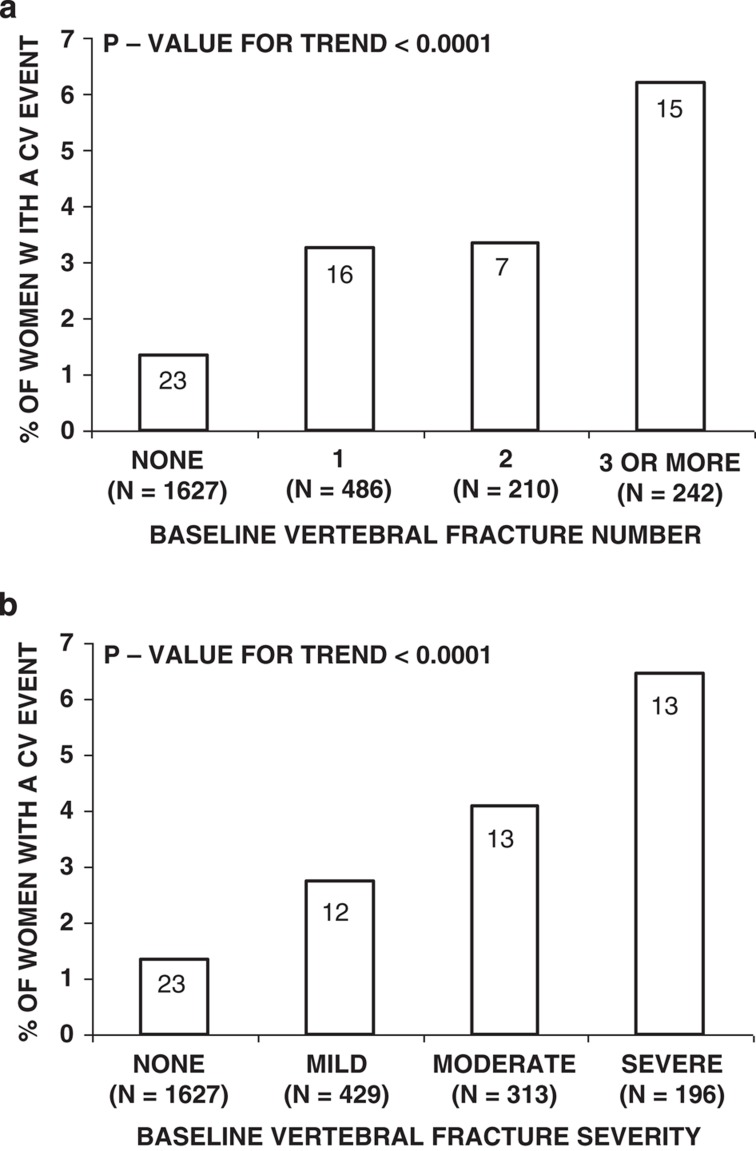

Furthermore, presence of fragility fracture is predictive of CVD. In the MORE study, the risk of cardiovascular event was higher in women with prevalent vertebral fractures and increased progressively with the number and with the severity of vertebral fractures38 (Figure 2). In the above Danish study, presence of vertebral fracture was associated with higher cardiovascular mortality.42 In a case–control study conducted in 8404 men and women identified in the Taiwanese healthcare database, the history of hip fracture conferred 50% higher risk of stroke after adjustment for heart disease, diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia.43 Given the design of the study, BMD or negative lifestyle factors were not assessed. Finally, in the Rochester Epidemiology Project, history of hip fracture was associated with higher risk of heart failure.44

Figure 2. Relationship between the (a) number and (b) severity of osteoporotic vertebral fractures and the risk of cardiovascular events in 2565 postmenopausal women from the placebo branch of the MORE study.

P-value is from Cochrane–Armitage trend test. Numbers in bars represent number of women with a cardiovascular event. Cardiovascular event is defined as the incident myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, or a stroke. Vertebral fractures were diagnosed using the semiquantitative method described by Genant. Fracture severity is shown in terms of magnitude of vertebral height reduction. Reproduced from Tanko et al.38 with permission from the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Lower 25OHD level is associated with higher incidence of CVD, especially myocardial infarction, and faster progression of AAC.45,46,47,48 This relation was observed in various populations, in both sexes and regardless of the design of the study (prospective cohort study, prospective nested case–control study, case–control study). This association remained significant after adjustment for potential confounders, which can be associated with bone and cardiovascular status independently of each other, such as age, exposure to sunlight, physical activity, smoking and season. Moreover, low 25OHD level was associated with higher cardiovascular mortality in a large group of men and women scheduled for coronary angiography and followed up prospectively for 7.7 years.49

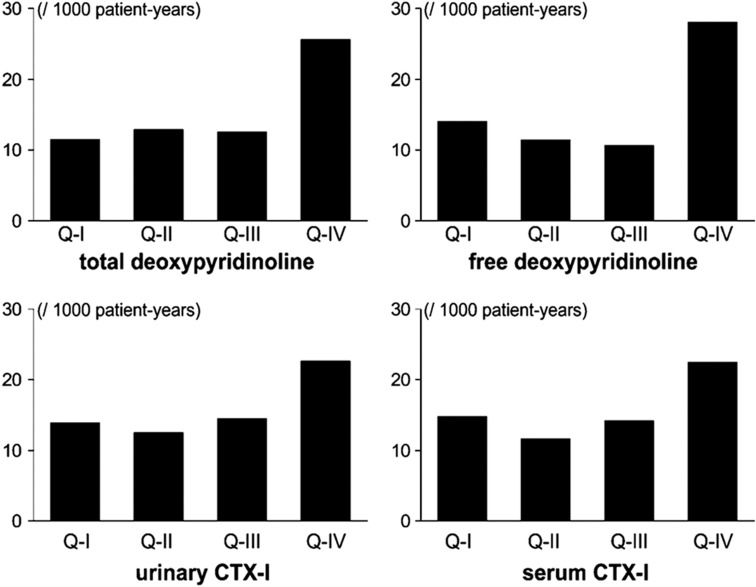

In a cohort of 744 men aged 50 years and older and followed up for 7.5 years, elevated levels of bone resorption markers were associated with higher risk of major cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke) after adjustment for confounders50 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Age-adjusted incidence of the major cardiovascular event in 744 men from the MINOS cohort according to the quartiles of the urinary excretion of total deoxypyridinoline (DPD) (top left graph), free DPD (top right graph), urinary CTX-I (bottom left graph) and serum CTX-I (bottom right graph).

Reproduced with permission from Szulc et al.50 with permission from the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

An important point that has emerged recently is the hormonal role of osteocalcin (OC) as a regulator of energetic metabolism. Experimental studies show that OC, especially its undercarboxylated form, promotes β-cell proliferation, insulin β-cell secretion and insulin sensitivity.51 Some,52,53,54 but not all,55 clinical studies showed that lower OC level is associated with higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, more severe AAC, higher brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and higher intima-media thickness.52,53,54 In Chinese men and women, higher OC level was associated with lower prevalence of ischemic heart disease.56 In a cohort of elderly men, men in the highest OC quintile and those in the lowest OC quintile had higher all-cause mortality compared with the second quintile.57 Cardiovascular mortality was also significantly higher in the highest OC quintile, whereas in the lowest OC quintile, the risk of cardiovascular mortality was not significant (HR=1.35, 95% CI: 0.82–2.22). Until now, clinical data on the association between OC and cardiovascular morbidity are scanty; however, they raise an interesting possibility of the pathophysiological pathway: bone–glucose metabolism–CVD.

Osteoporosis and CVD—consistency and inconsistency

The association between osteoporosis and CVD is driven by severe forms of both diseases. The associations are significant in the studies, which assess fragility fractures, mainly hip fracture on the side of osteoporosis and, on the side of CVD, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure or severe AAC.1,5,6,25,35,38,43 By contrast, the results are less consistent in the studies in which mild forms of these pathologies were also taken into account.2,10,11,21,41 More importantly, concomitant heart failure is a risk factor of mortality in hip fracture patients, whereas hip fracture confers a risk of mortality in patients with heart failure.58,59,60

The associations between CVD (especially AAC) and measures of osteoporosis (BMD, rate of bone loss, fracture incidence) are stronger in women than in men. In postmenopausal women, bone loss is faster than in men. Thus, in women, BMD and fracture risk depend more strongly on the postmenopausal bone loss, whereas in older men, BMD is more strongly determined by the peak BMD. This difference between men and women may accentuate the importance of the aging-related factors as the determinants of the association between osteoporosis and CVD. Obviously, the importance of the genetic and growth-related factors should not be underestimated; however, their role in the pathogenesis of these disease in older individuals remains to be established.61

Furthermore, the sufficient number of events and temporal closeness are necessary to detect the association. The association has not been detected in small groups, especially composed of younger individuals without severe CVD, or in the long-term follow-up with a large time-lapse between the cardiovascular event (or the assessment of cardiovascular status) and fracture event. In addition, low BMD, fragility fractures, severe AAC and CVD, especially major cardiovascular events, are all associated with higher mortality. Thus, the individuals with severe forms of these diseases are less likely to survive and this differential survival can make the association harder to detect.

The association between both diseases remains significant after adjustment for shared risk factors. However, the presence and intensity of some risk factors (for example, lifestyle factors or comorbidities) are self-reported and not further ascertained. Then, in the analysis, they are often dichotomized or categorized into a small number of classes. Comorbidities are most often dichotomized and their duration and severity are not taken into account. Treatment and its duration as well as dose of drug and compliance to treatment are not taken into account either. However, in some types of CVD for which various classes of medications are available, for example, hypertension, medication as well as its dose and duration of treatment may also impact on the fracture risk.62

The assessment of some risk factors, such as hyperlipidaemia or inflammatory markers, is based on one measurement. Thus, their real effect cannot be correctly appreciated. This limitation of the statistical analyses may underestimate the role of the shared risk factors and falsely overestimate the strength of the part of the link between osteoporosis and CVD, which is independent of the shared risk factors.

Many studies show the role of the 'bone risk factors' in the regulation of cardiovascular metabolism and vice versa. Vitamin D deficit may be associated with higher activity of the renin–angiotensin system and impaired glucose tolerance.63,64 Some factors may have parallel, independent negative effects on bone and cardiovascular metabolism. For instance, homocysteine may promote aortic calcification and reduce bone resistance.65,66 Higher levels of the glycation end products (AGEs), for example, pentosidine, were associated with poor bone and cardiovascular status. On one hand, accumulation of pentosidine in the trabecular bone was associated with lower bone strength after adjustment for BMD.67 On the other hand, higher AGE levels were associated with higher risk of cardiovascular event.68

General summary and conclusions

The experimental and clinical studies show a significant positive association between severe forms of osteoporosis and of CVD. They suggest that this association depends partially on the shared risk factors, for example, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, hormonal deficits, vitamin D deficit, AGE accumulation. From the clinical point of view, it seems that patients with severe form of osteoporosis would benefit from a detailed assessment of the cardiovascular status, whereas patients with severe CVD would benefit from the assessment of BMD and other bone-related parameters. However, official guidelines that could be recommended for the clinical practice are still lacking.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bagger YZ, Tankó LB, Alexandersen P, Qin G, Christiansen C. Radiographic measure of aorta calcification is a site-specific predictor of bone loss and fracture risk at the hip. J Intern Med 2006;259:598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TK, Bolland MJ, Pelt NC, Horne AM, Mason BH, Ames RW et al. Relationships between vascular calcification, calcium metabolism, bone density, and fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2010;25:2501–2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naves M, Rodríguez-García M, Díaz-López JB, Gómez-Alonso C, Cannata-Andía JB. Progression of vascular calcifications is associated with greater bone loss and increased bone fractures. Osteoporos Int 2008;19:1161–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajzbaum G, Roger VL, Bézie Y, Chauffert M, Bréville P, Roux F et al. French women, fractures and aortic calcifications. J Intern Med 2005;257:117–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szulc P, Kiel DP, Delmas PD. Calcifications in the abdominal aorta predict fracturesin men: MINOS study. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz E, Arfai K, Liu X, Sayre J, Gilsanz V. Aortic calcification and the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:4246–4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat GN, Cauley JA, Matthews KA, Newman AB, Johnston J, Mackey R et al. Volumetric BMD and vascular calcification in middle-aged women: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. J Bone Miner Res 2006;21:1839–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyder JA, Allison MA, Wong N, Papa A, Lang TF, Sirlin C et al. Association of coronary artery and aortic calcium with lumbar bone density: the MESA Abdominal Aortic Calcium Study. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:186–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divers J, Register TC, Langefeld CD, Wagenknecht LE, Bowden DW, Carr JJ et al. Relationships between calcified atherosclerotic plaque and bone mineral density in African Americans with type 2 diabetes. J Bone Miner Res 2011;26:1554–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat GN, Strotmeyer ES, Newman AB, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Bauer DC, Harris T et al. Volumetric and areal bone mineral density measures are associated with cardiovascular disease in older men and women: the health, aging, and body composition study. Calcif Tissue Int 2006;79:102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi K, Ross PD, Orloff J, Davis JW, Katagiri H, Wasnich RD. Low bone density is not associated with aortic calcification. Calcif Tissue Int 2001;69:20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Bielak LF, Streeten EA, Ryan KA, Rumberger JA, Sheedy PF 2nd et al. Relationship between vascular calcification and bone mineral density in the Old-order Amish. Calcif Tissue Int 2007;80:244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye MA, Melton LJ 3rd, Bryant SC, Fitzpatrick LA, Wahner HW, Schwartz RS et al. Osteoporosis and calcification of the aorta. Bone Miner 1992;19:185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Klift M, Pols HA, Hak AE, Witteman JC, Hofman A, de Laet CE. Bone mineral density and the risk of peripheral arterial disease: the Rotterdam Study. Calcif Tissue Int 2002;70:443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SY, Kwok T, Woo J, Lynn H, Griffith JF, Leung J et al. Bone mineral density and the risk of peripheral arterial disease in men and women: results from Mr and Ms Os, Hong Kong. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:1933–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche M, Pouilles JM, Ribot C, Bendayan P, Bernard J, Boccalon H et al. Comparison of the bone mineral content of the lower limbs in men with ischaemic atherosclerotic disease. Clin Rheumatol 1994;13:611–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz JA, Morris CD, Roberts LA, McClung MR, McCarron DA. Blood pressure and calcium intake are related to bone density in adult males. Br J Nutr 1999;13:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hak AE, Pols HA, van Hemert AM, Hofman A, Witteman JC. Progression of aortic calcification is associated with metacarpal bone loss during menopause: a population based longitudinal study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000;13:1926–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel DP, Kauppila LI, Cupples LA, Hannan MT, O'Donnell CJ, Wilson PW. Bone loss and the progression of abdominal aortic calcification over a 25 year period: the Framingham Heart Study. Calcif Tissue Int 2001;13:271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio FP, Meilahn E, Zmuda JM, Cauley JA. High blood pressure and bone-mineral loss in elderly white women: a prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Lancet 1999;354:971–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins TC, Ewing SK, Diem SJ, Taylor BC, Orwoll ES, Cummings SR et al. Peripheral arterial disease is associated with higher rates of hip bone loss and increased fracture risk in older men. Circulation 2009;119:2305–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sennerby U, Melhus H, Gedeborg R, Byberg L, Garmo H, Ahlbom A et al. Cardiovascular diseases and risk of hip fracture. JAMA 2009;302:1666–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber Y, Melton LJ 3rd, Weston SA, Roger VL. Association between myocardial infarction and fractures: an emerging phenomenon. Circulation 2011;124:297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Hypertension is a risk factor for fractures. Calcif Tissue Int 2009;84:103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Diepen S, Majumdar SR, Bakal JA, McAlister FA, Ezekowitz JA. Heart failure is a risk factor for orthopedic fracture: a population-based analysis of 16,294 patients. Circulation 2008;118:1946–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone L, Buzková P, Fink HA, Lee JS, Chen Z, Ahmed A et al. Hip fractures and heart failure: findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Eur Heart J 2010;31:77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar SR, Ezekowitz JA, Lix LM, Leslie WD. Heart failure is a clinically and densitometrically independent risk factor for osteoporotic fractures: population-based cohort study of 45,509 subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:1179–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kado DM, Lui LY, Cummings SR. Rapid resting heart rate: a simple and powerful predictor of osteoporotic fractures and mortality in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flipon E, Liabeuf S, Fardellone P, Mentaverri R, Ryckelynck T, Grados F et al. Is vascular calcification associated with bone mineral density and osteoporotic fractures in ambulatory, elderly women? Osteoporos Int 2011;23:1533–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samelson EJ, Cupples LA, Broe KE, Hannan MT, O'Donnell CJ, Kiel DP. Vascular calcification in middle age and long-term risk of hip fracture: the Framingham Study. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:1449–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto J, Matsumoto H, Takeda T, Sato Y, Uzawa M. A radiographic study on the associations of age and prevalence of vertebral fractures with abdominal aortic calcification in Japanese postmenopausal women and men. J Osteoporos 2010;2010:748380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Kim YM, Cho MA, Rhee Y, Hur KY, Kang ES et al. Echogenic carotid artery plaques are associated with vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. Calcif Tissue Int 2008;82:411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mühlen D, Allison M, Jassal SK, Barrett-Connor E. Peripheral arterial disease and osteoporosis in older adults: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Osteoporos Int 2009;20:2071–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison EM, Compston JE, Flahive J, Siris ES, Gehlbach SH, Adachi JD et al. Effect of co-morbidities on fracture risk: findings from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Bone 2012;50:1288–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sennerby U, Farahmand B, Ahlbom A, Ljunghall S, Michaëlsson K. Cardiovascular diseases and future risk of hip fracture in women. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:1355–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browner WS, Pressman AR, Nevitt MC, Cauley JA, Cummings SR. Association between low bone density and stroke in elderly women. The study of osteoporotic fractures. Stroke 1993;24:940–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordström A, Eriksson M, Stegmayr B, Gustafson Y, Nordström P. Low bone mineral density is an independent risk factor for stroke and death. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;29:130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tankó LB, Christiansen C, Cox DA, Geiger MJ, McNabb MA, Cummings SR. Relationship between osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 2005;20:1912–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiklund P, Nordström A, Jansson JH, Weinehall L, Nordström P. Low bone mineral density is associated with increased risk for myocardial infarction in men and women. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samelson EJ, Kiel DP, Broe KE, Zhang Y, Cupples LA, Hannan MT et al. Metacarpal cortical area and risk of coronary heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat GN, Newman AB, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Matthews KA, Boudreau R, Schwartz AV et al. The association of bone mineral density measures with incident cardiovascular disease in older adults. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Recke P, Hansen MA, Hassager C. The association between low bone mass at the menopause and cardiovascular mortality. Am J Med 1999;106:273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JH, Chung SD, Xirasagar S, Jaw FS, Lin HC. Increased risk of stroke in the year after a hip fracture: a population-based follow-up study. Stroke 2011;42:336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber Y, Melton LJ 3rd, Weston SA, Roger VL. Osteoporotic fractures and heart failure in the community. Am J Med 2011;124:418–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scragg R, Jackson R, Holdaway IM, Lim T, Beaglehole R. Myocardial infarction is inversely associated with plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels: a community-based study. Int J Epidemiol 1990;19:559–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Hollis BW, Rimm EB. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of myocardial infarction in men: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1174–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, Jacques PF, Ingelsson E, Lanier K et al. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2008;117:503–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naves-Díaz M, Cabezas-Rodríguez I, Barrio-Vázquez S, Fernández E, Díaz-López JB, Cannata-Andía JB. Low calcidiol levels and risk of progression of aortic calcification. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:1177–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobnig H, Pilz S, Scharnagl H, Renner W, Seelhorst U, Wellnitz B et al. Independent association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d levels with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1340–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szulc P, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP, Delmas PD. Increased bone resorption is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events in men: the MINOS study. J Bone Miner Res 2009;24:2023–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, Ferron M, Ahn JD, Confavreux C et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell 2007;130:456–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem U, Mosley TH Jr, Kullo IJ. Serum osteocalcin is associated with measures of insulin resistance, adipokine levels, and the presence of metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010;30:1474–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Confavreux CB, Szulc P, Boutroy S, Varennes A, Vilayphiou N, Goudable J et al. Association of serum osteocalcin and aortic calcifications in men from the MINOS study. Osteoporos Int 2012;23 (Suppl 2): S360, Poster P668. [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa I, Yamaguchi T, Yamamoto M, Yamauchi M, Kurioka S, Yano S et al. Serum osteocalcin level is associated with glucose metabolism and atherosclerosis parameters in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker BD, Bauer DC, Ensrud KE, Ix JH. Association of osteocalcin and abdominal aortic calcification in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Calcif Tissue Int 2010;86:185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Qi L, Gu W, Yan Q, Dai M, Shi J et al. Relation of serum osteocalcin level to risk of coronary heart disease in Chinese adults. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:1461–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeap BB, Chubb SA, Flicker L, McCaul KA, Ebeling PR, Hankey GJ et al. Associations of total osteocalcin with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in older men. The Health In Men Study. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen MW, Gullerud RE, Larson DR, Melton LJ 3rd, Huddleston JM. Impact of heart failure on hip fracture outcomes: a population-based study. J Hosp Med 2011;6:507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost SA, Nguyen ND, Black DA, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Risk factors for in-hospital post-hip fracture mortality. Bone 2011;49:553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia SC, Gross CP, Chaudhry SI, Ning YM, Leo-Summers L, Van Ness PH et al. Impact of Comorbidity on Mortality Among Older Persons with Advanced Heart Failure. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:513–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini F, Brandi ML. Genetic determinants of osteoporosis: common bases to cardiovascular diseases? Int J Hypertens 2010;pii:394579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon DH, Mogun H, Garneau K, Fischer MA. Risk of fractures in older adults using antihypertensive medications. J Bone Miner Res 2011;26:1561–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Kong J, Wei M, Chen ZF, Liu SQ, Cao LP. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest 2002;110:229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittas AG, Lau J, Hu FB, Dawson-Hughes B. The role of vitamin D and calcium in type 2 diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:2017–2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Campenhout A, Moran CS, Parr A, Clancy P, Rush C, Jakubowski H et al. Role of homocysteine in aortic calcification and osteogenic cell differentiation. Atherosclerosis 2009;202:557–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Marumo K. Collagen cross-links as a determinant of bone quality: a possible explanation for bone fragility in aging, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos Int 2010;21:195–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viguet-Carrin S, Roux JP, Arlot ME, Merabet Z, Leeming DJ, Byrjalsen I et al. Contribution of the advanced glycation end product pentosidine and of maturation of type I collagen to compressive biomechanical properties of human lumbar vertebrae. Bone 2006;39:1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nin JW, Jorsal A, Ferreira I, Schalkwijk CG, Prins MH, Parving HH et al. Higher plasma levels of advanced glycation end products are associated with incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in type 1 diabetes: a 12-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care 2011;34:442–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]