Abstract

Organic dust exposure within agricultural environments results in airway diseases. Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 only partly account for the innate response to these complex dust exposures. To determine the central pathway in mediating complex organic dust–induced airway inflammation, this study targeted the common adaptor protein, myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88), and investigated the relative contributions of receptors upstream from this adaptor. Wild-type, MyD88, TLR9, TLR4, IL-1 receptor I (RI), and IL-18R knockout (KO) mice were challenged intranasally with organic dust extract (ODE) or saline, according to an established protocol. Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) was assessed by invasive pulmonary measurements. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was collected to quantitate leukocyte influx and cytokine/chemokine (TNF-α, IL-6, chemokine [C-X-C motif] ligands [CXCL1 and CXCL2]) concentrations. Lung tissue was collected for histopathology. Lung cell apoptosis was determined by a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling assay, and lymphocyte influx and intercellular adhesion molecule–1 (ICAM-1) expression were assessed by immunohistochemistry. ODE-induced AHR was significantly attenuated in MyD88 KO mice, and neutrophil influx and cytokine/chemokine production were nearly absent in MyD88 KO animals after ODE challenges. Despite a near-absent airspace inflammatory response, lung parenchymal inflammation was increased in MyD88 KO mice after repeated ODE exposures. ODE-induced epithelial-cell ICAM-1 expression was diminished in MyD88 KO mice. No difference was evident in the small degree of ODE-induced lung-cell apoptosis. Mice deficient in TLR9, TLR4, and IL-18R, but not IL-1IR, demonstrated partial protection against ODE-induced neutrophil influx and cytokine/chemokine production. Collectively, the acute organic dust–induced airway inflammatory response is highly dependent on MyD88 signaling, and is dictated, in part, by important contributions from upstream TLRs and IL-18R.

Keywords: MyD88, lung, Toll-like receptor, IL-1R/IL-18R, organic dust

The inhalation of organic dusts or bioaerosols in agricultural environments can result in inflammatory respiratory diseases, including asthma, chronic bronchitis, and obstructive lung disease (1). Exposure to these organic dusts results in airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) to methacholine, neutrophil influx, and increases in TNF-α, IL-6, and neutrophil chemoattractants (human CXCL8, and murine CXCL1 and CXCL2) (1). However, children raised on farms were reported to be protected against the development of atopy and IgE-mediated asthma (2). These organic dust exposure environments are increasingly recognized as complex, comprising a wide diversity of microbial motifs (1). However, the mechanisms underlying the host’s airway immune response remain unclear.

The activity of endotoxin, a cell-wall component of Gram-negative bacteria, does not completely explain the consequences of organic dust–induced respiratory disease, particularly within animal feeding operations (1, 3, 4). Indeed, upon the removal of endotoxin, organic dust extracts retain a significant ability to elicit proinflammatory mediator production from various cell types (1, 5, 6). Human endotoxin inhalation and swine barn exposure challenges do not produce similar inflammatory responses, even when the concentration of pure endotoxin was 200-fold higher than the measured swine barn endotoxin concentration (4). Mice deficient in the endotoxin-recognition receptor, Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), demonstrate an incomplete reduction in swine barn air–induced neutrophil influx, with no reduction in exposure-induced cytokine/chemokine production or AHR (7). However, persons with a TLR4 variant (299/399) demonstrate modest protection against cross-shift lung function decline after a high endotoxin, but not low endotoxin, swine barn exposure challenge (8). These studies suggest that non-endotoxin–mediated pathways are important in responding to complex organic dust exposures.

Recent studies identified an abundance and diversity of Gram-positive bacteria in animal feeding confinement operations (6, 9–11). Furthermore, Archaeobacteria and fungi have also been detected in varying amounts, depending on the geographic region (2, 12). TLR2, which forms heterodimers with TLR1 or TLR6 to recognize and respond to peptidoglycans, lipoproteins, and lipoteichoic acids of Gram-positive bacteria, has been implicated in mediating organic dust–induced airway disease (13–15). More specifically, swine facility organic dust extract (ODE)–induced airway neutrophil influx, cytokine/chemokine production, and lung parenchymal infiltrates were reduced, but not completely abrogated, in TLR2-deficient mice (14). These observations suggest that targeting one pattern-recognition receptor pathway may not fully explain the airway inflammatory response to complex organic dust exposures. These observations further suggest that alternative pathways (i.e., non-TLR) mediate airway inflammatory responses.

A potential downstream pathway to account for the airway response to organic dust exposures involves the adaptor protein myeloid differentiation factor–88 (MyD88), which is used by all TLRs, except for TLR3 (16). In addition to TLR signaling, receptors for the IL-1 family (e.g., IL-1IR and IL-18R) use the MyD88 adaptor protein to transduce activation signals (16). We hypothesized that a MyD88-dependent pathway was primarily responsible for mediating acute organic dust–induced airway inflammatory consequences. To test this hypothesis, MyD88 knockout (KO) mice were treated with ODE, and dust-induced airway inflammatory consequences, including AHR, leukocyte influx, cytokine/chemokine production, and histopathology, were evaluated. Because our studies demonstrated a central role for MyD88, the relative contributions of several potential upstream targets, including TLR9, TLR4, IL-1R, and IL-18R, were also investigated. Important roles for TLR9, TLR4, and IL-18R, in addition to the previously reported role for TLR2 (14), were also found.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) and IL-1R (KO, Il1r1tm1Roml−/−) and IL-18 (Il18tm1Aki−/−) KO mice on a C57BL/6 background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). MyD88, TLR9, and TLR4 KO mice on a C57BL/6 background were provided by Dr. S. Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). Animal procedures were approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, according to guidelines from the National Institutes of Health for the use of rodents.

Organic Dust Extract

Aqueous ODE was collected from swine confinement feeding operations and prepared as previously described (14), and as detailed in the online supplement.

Murine Model

Mice received an intranasal inhalation of 50 μl sterile saline (PBS) or 12.5% ODE, according to an established protocol (17). No mice exhibited respiratory distress throughout the treatment period.

Invasive Pulmonary Function Measurement

AHR was invasively assessed by direct airway resistance, using a computerized small-animal ventilator (Finepointe; Buxco Electronics, Wilmington, NC), as previously described (17). Dose responsiveness to aerosolized methacholine (0–96 mg/ml) was obtained, and is reported as total lung resistance (RL).

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid Cell and Cytokine/Chemokine Analysis

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was achieved using 3 × 1 ml PBS, and the total cell number recovered from pooled lavages was enumerated and differential cell counts were determined, using cytospin-prepared slides (Cytopro Cytocentrifuge; Wescor, Inc., Logan, UT) stained with Diff-Quik (Siemens, Newark, DE). From the cell-free supernatant of the first lavage, TNF-α, IL-6, keratinocyte chemoattractant (CXCL1), and macrophage inflammatory protein–2 (CXCL2) were quantitated via ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) with sensitivities of 10.9, 7.8, 15.6, and 7.8 pg/ml, respectively.

Histopathology

Whole lungs were excised and inflated to 20 cm H2O pressure with 10% formalin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (17). Entire lung sections (4–5 μm) were microscopically reviewed and semiquantitatively assessed for the degree and distribution of lung inflammation by a pathologist blinded to the treatment conditions, using a previously published scoring system (14, 17). Each inflammatory parameter was independently assigned a value from 0–3, with higher scores reflecting greater inflammatory changes in the lung.

Immunohistochemistry and Apoptosis Assay

Lung-section slides were analyzed for CD3 (pan-T cell marker; rabbit anti-CD3, 1:300; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) and CD45R/B220 (pan-B cell murine marker; rat anti-CD45R/B220, 1:200; BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) and intercellular adhesion molecule–1 (ICAM-1) expression (rat anti-CD54, 1:300; Biolegend, San Diego, CA) by immunohistochemistry methods, as previously described (17). Apoptotic lung cells were determined by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining of tissue sections, using the ApopTag Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slide scanning and scoring are described in the online supplement.

Statistical Methods

Data are presented as the means and standard errors of the mean. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA and the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, where appropriate. For methacholine dose-response curves, two-way ANOVA was applied (because two independent variables are involved, i.e., treatment group and methacholine dose), followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests when group differences were significant (P < 0.05). GraphPad version 5.01 software (La Jolla, CA) was used.

Results

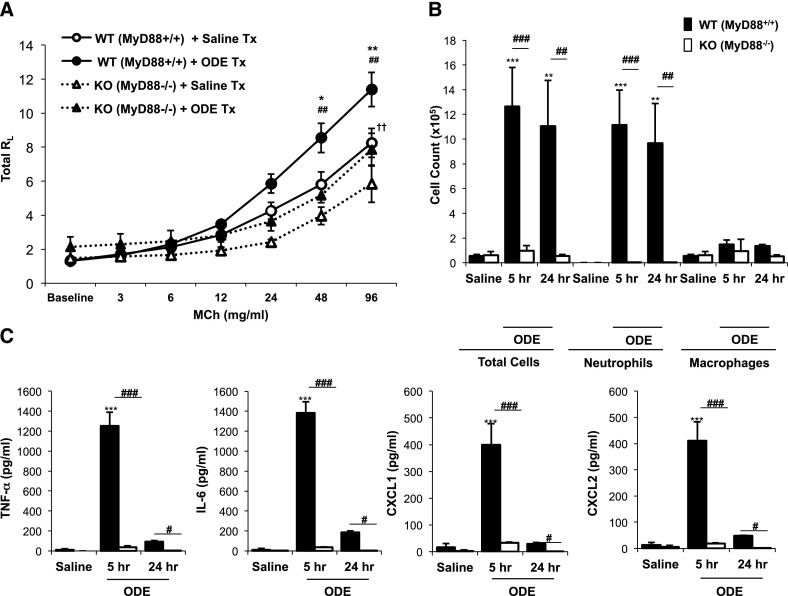

Organic Dust–Induced AHR Is MyD88-Dependent

AHR after acute swine facility organic dust exposure is a feature observed in humans and modeled in mice (4, 17). MyD88 KO mice displayed a significant reduction in ODE-induced AHR, compared with WT mice (P < 0.05; Figure 1A). In addition, MyD88 KO animals demonstrated a generally diminished AHR response to methacholine, because saline-treated MyD88 KO mice manifested significantly reduced AHR, compared with saline-treated WT mice (P < 0.05; Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Organic dust extract (ODE)–induced airway hyperresponsiveness, neutrophil influx, and cytokine/chemokine production are reduced in myeloid differentiation factor–88 (MyD88) knockout (KO) mice. (A) Wild-type (WT, circles and solid lines) and MyD88 knockout (triangles and dotted lines) mice were treated with ODE (solid symbols) or saline (open symbols), and total lung resistance (RL) was directly measured at 3 hours after exposure (mean ± SEM, n = 4–5 mice/group). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, compared with WT + ODE/WT + saline mice. ##P < 0.01, compared with WT + ODE/KO + ODE mice. ††P < 0.01, compared with WT + saline/KO + saline mice. WT and MyD88 KO mice were treated with saline or ODE, and their bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected at 5 and 24 hours after exposure. Total cells and cell differentials (B) and BALF supernatant cytokines/chemokines (C) are shown (mean ± SEM, n = 4–5 mice/group). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, compared with saline/ODE mice. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001, compared with WT/KO mice as noted by line. MCh, methacholine; Tx, treatment.

Acute Dust-Induced Airway Neutrophil Influx and Cytokine/Chemokine Release Is Nearly Abolished in the BAL Fluid of MyD88 KO Mice

ODE treatment induced neutrophil recruitment and cytokine/chemokine production in WT mice at 5 hours. However, minimal evidence was found of neutrophil recruitment or TNF-α, IL-6, CXCL1, and CXCL2 release in the BAL fluid (BALF) of MyD88 KO animals after a single exposure to ODE (Figures 1B and 1C). No significant increases in macrophages or lymphocytes were evident in either WT or MyD88 KO mice at these early intervals (Figure 1B, and data not otherwise shown). We also determined whether MyD88 mice would exhibit a delayed increase in airway neutrophil influx and/or cytokine/chemokine production after ODE exposure. However, no compensatory increase in these inflammatory indices was evident at 24 hours after ODE treatment (Figures 1B and 1C). ODE-induced cytokine/chemokine production was reduced in WT animals at 24 hours compared with 5 hours, consistent with the kinetics of these mediators (14). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the MyD88 signaling pathway is central in responding to acute swine facility organic dust exposure in the airway.

Exploring the Involvement of Alternative MyD88-Dependent Receptors in Mediating Airway Inflammation in Response to ODE

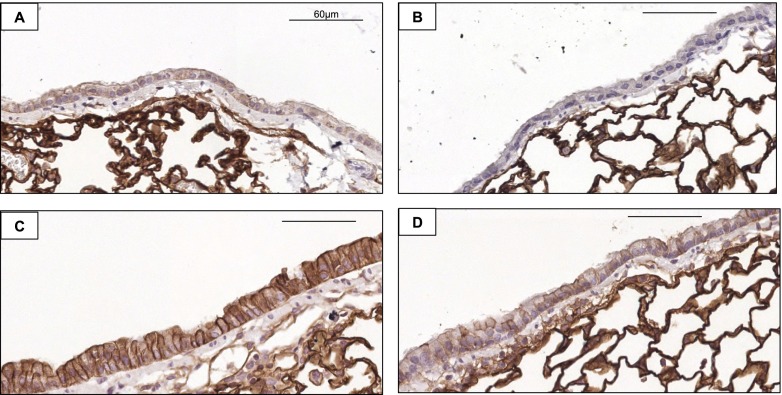

Because TLR2 and TLR4 only partly accounted for swine barn organic dust–induced airway inflammatory consequences (7, 14), alternative receptors that also use MyD88 were investigated for a further delineation of other important contributors to the observed MyD88-dependent response. Because organic dusts from swine confinements contain bacterial DNA (9, 11, 12) and TLR9 recognizes unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) oligodeoxynucleotides motifs in bacterial DNA (18), we hypothesized that TLR9 would perform a functional role. was Although we observed no statistically significant reduction in neutrophil, macrophage, and lymphocyte influx in ODE-treated TLR9 KO mice compared with WT mice (P > 0.05; Figure 2A, and data not otherwise shown), partial but significant reductions in TNF-α, IL-6, CXCL1, and CXCL2 concentrations were detected in BALF after ODE challenge in TLR9 KO mice compared with WT animals (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Toll-like receptor–9 (TLR9) affects acute ODE-induced airway inflammation. Wild-type (WT) and TLR9 knockout (KO) mice were treated once with saline or ODE, and the BALF was collected 5 hours later. Total cells and cell differentials (A) and cytokines/chemokines in BALF (B) are shown (mean ± SEM, n = 4 mice/group). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, compared with saline/ODE mice. ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001, compared with WT/KO mice.

Although others have shown that endotoxin-resistant mice are partly protected from swine barn air–induced airway inflammation (7), we investigated the acute airway inflammatory response in TLR4 KO mice, using our intranasal inhalation model for purposes of direct comparisons. We observed partial but incomplete reductions in ODE-induced airway inflammatory responses in TLR4 KO mice compared with WT mice (Figures E1A and E1B in the online supplement). More specifically, we observed significant reductions in neutrophil influx (∼ 40%), TNF-α release (∼ 60%), and IL-6 (∼ 25%), but no reductions in CXCL1 and CXCL2 release, as determined in BALF from ODE-treated animals between TLR4 KO and WT mice.

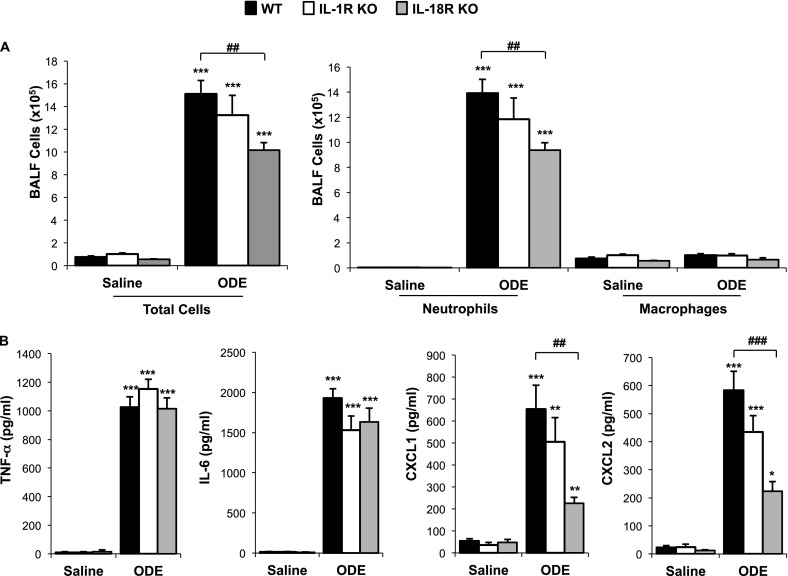

MyD88 is also used as a signaling adaptor for the IL-1I and IL-18 receptors, and therefore we investigated whether these receptors would be important contributors in the MyD88-dependent response to ODE. We observed a statistically significant reduction in ODE-induced neutrophil recruitment in IL-18RI KO mice (P < 0.001), but not IL-1R KO mice (P > 0.05), compared with WT mice (Figure 3A). Moreover, significant reductions were observed in ODE-stimulated CXCL1 and CXCL2 BALF concentrations in IL-18R KO mice, but not IL-1RI KO mice, compared with WT mice (P < 0.05; Figure 3B). Together, these experiments demonstrate that the MyD88-pathway upstream receptors TLR9, TLR4, and IL-18R, in addition to TLR2 as implicated in previous work (14), are contributing to acute organic dust–induced airway responses.

Figure 3.

Effects of IL-1 receptor (R) and IL-18R in mediating acute ODE-induced airway inflammation. Wild-type (WT), IL-1RI knockout (KO), and IL-18R KO mice were treated with saline or ODE once, and the BALF was collected 5 hours after exposure. Total cells and cell differentials (A) and BALF supernatant cytokines/chemokines (B) are shown (mean ± SEM, n = 4 mice/group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, compared with saline/ODE mice. ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001, compared with WT/KO mice.

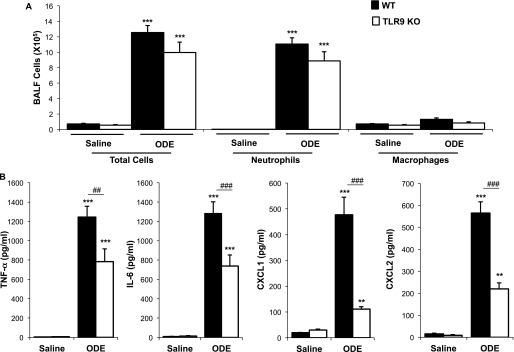

Neutrophil Influx and Cytokine/Chemokine Release in BALF Remains Blunted in MyD88 KO Mice after Repeated ODE Treatments

Because MyD88-deficient mice demonstrated a strong phenotype in response to a one-time challenge with ODE, we focused the remainder of our experiments on these mice, for a fuller understanding of their altered airway response. In these experiments, we determined whether the reduction of airway inflammatory indices in MyD88 KO mice after a single ODE treatment (Figure 1) would persist after repeated ODE challenges. WT and MyD88 KO animals were treated daily for 3 or 7 days with ODE or saline, whereupon BALF was collected 5 hours after the final treatment. As compared with saline, repeated ODE challenges resulted in increased neutrophil, macrophage, and lymphocyte influx into the airways of WT mice (Figure 4A). We also observed a small but statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase in BALF leukocytes in MyD88 KO mice after repeated ODE challenges, compared with saline (Figure 4A). However, the magnitude of the ODE-induced neutrophil influx remained significantly reduced in MyD88 KO animals compared with WT animals (P < 0.001 at 3 days, and P < 0.01 at 7 days; Figure 4A). In addition, ODE treatment increased cytokine/chemokine concentrations at 3 and 7 days in WT mice, but we observed little evidence of TNF-α, IL-6, CXCL1, and CXCL2 production in the BALF of MyD88 KO animals after repeated ODE administrations (Figure 4B). These experiments demonstrate that MyD88-deficient mice produce a near-absent inflammatory cellular influx and cytokine/chemokine release in lavage fluid after repetitive ODE treatments.

Figure 4.

BALF airway inflammatory indices remained reduced after repeated ODE challenges in MyD88 KO mice. Wild-type (WT) and MyD88 knockout (KO) mice were treated with ODE for 3 or 7 days, and BALF was collected at 5 hours after the final ODE exposure. Total cells and cell differentials (A) and cytokines/chemokines in BALF (B) are shown (mean ± SEM, n = 4–6 mice/group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, compared with saline/ODE mice. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001, compared with WT/KO mice.

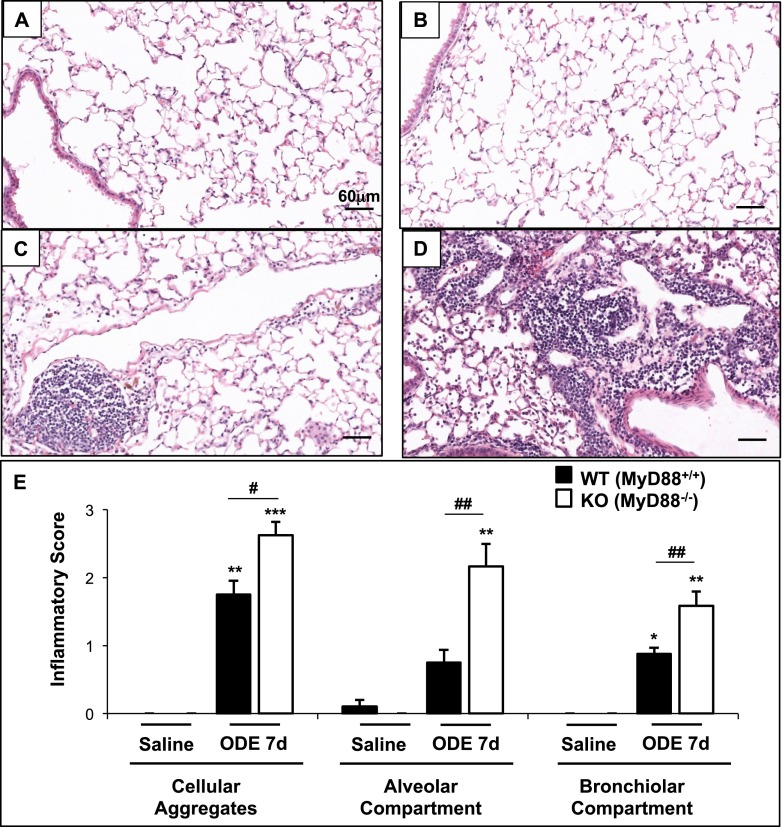

MyD88 KO Mice Display Increased Lung Inflammatory Histopathology after Repeated ODE Challenges

We next investigated whether the loss of MyD88 would affect repeated ODE-induced lung parenchymal inflammation at 7 days after repeated ODE exposure, because this time point demonstrated significant lung parenchymal inflammatory changes in WT mice. ODE treatment increased lung inflammatory histopathology, compared with saline (Figures 5A–5D). To assess the ranges of ODE-induced histopathologic changes semiquantitatively, tissue inflammatory scores were determined. ODE-treated MyD88 KO mice displayed significant increases in all inflammatory parameters, including cellular aggregates and alveolar and bronchiolar compartment inflammation, compared with WT animals (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Organic dust–induced inflammation in the lung parenchyma is augmented in MyD88 KO mice. Representative murine lung sections (hematoxylin-and-eosin stain, ×20 magnification) treated for 7 days illustrate saline-treated WT (A) and MyD88 KO (B) mice, and ODE-treated WT (C) and MyD88 KO (D) mice. (E) Semiquantitative lung inflammatory scores (mean ± SEM, n = 4–6 mice/group) are shown. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, compared with saline/ODE mice. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01, compared with WT/KO mice.

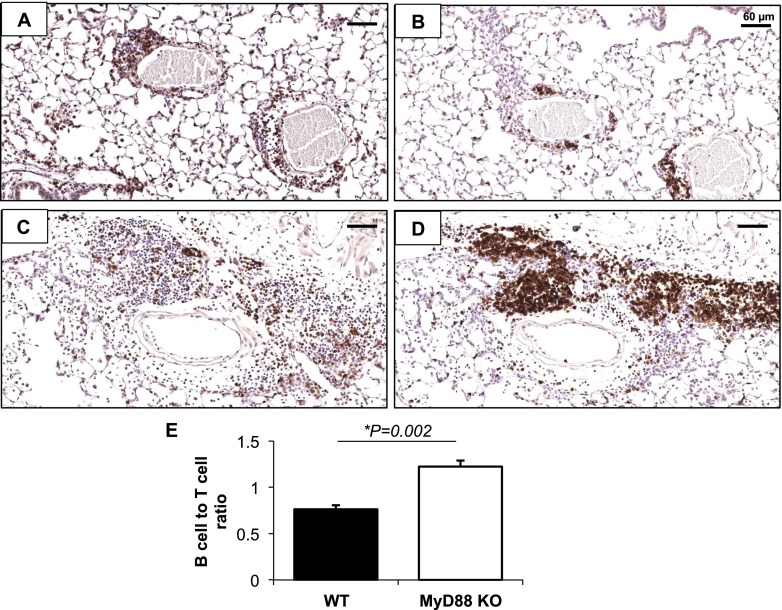

Composition of Lung Parenchymal Cellular Aggregates

Based on enhancements in the distribution, number, and size of cellular aggregates in the lung parenchyma of ODE-exposed MyD88 KO mice compared with WT mice, we determined the composition of these cells by immunohistochemical staining. Similar to previous findings (17), ODE-induced cellular aggregates represented an admixture of T cells and B cells (Figures 6A–6E). In comparison with WT animals, a significant increase was evident in the proportion of B cells to T cells in the aggregates of ODE-exposed MyD88 KO mice. A small number of apoptotic lung cells were detected in the aggregates after repeated ODE challenges. However, we observed no significant differences in the frequency of apoptotic lung cells between MyD88 KO and WT mice (see Figures E1A–E1C in the online supplement). Collectively, these experiments demonstrated an enhanced lung parenchymal inflammatory response after repeated ODE exposures in MyD88 KO mice, despite a profound reduction in lavage fluid inflammatory mediators and cells.

Figure 6.

Composition of organic dust–induced cellular aggregates. Lung sections from WT and MyD88−/− mice, treated for 7 days with ODE, were stained for T cells (CD3) and B cells (CD45R/B220). Representative images show CD3 staining of WT (A) and KO (B) mice, and B220 staining of WT (C) and KO (D) mice (×20 magnification). (E) Quantitative assessment of B-cell/T-cell ratio (n = 4 mice/group).

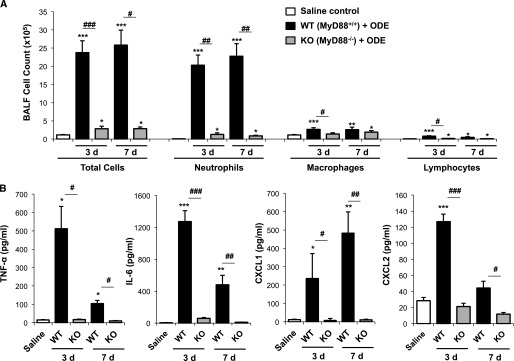

ODE-Induced Epithelial Cell ICAM-1 Expression Is Reduced in MyD88 KO Mice

In addition to the role of chemoattractant molecules in directing leukocyte migration to the airway, adhesion molecules are also recognized as important in orchestrating leukocyte migration, and moreover, previous studies reported increased bronchial epithelial-cell ICAM-1 expression after exposure to hog barn extracts (19). For these reasons, we investigated epithelial-cell ICAM-1 expression by immunohistochemical methods because we hypothesized that ICAM-1 expression would be reduced in ODE-treated MyD88 KO animals, potentially explaining our observations of reduced inflammatory cellular influx into the airspace (lavage fluid). Our experiments revealed that epithelial-cell ICAM-1 expression was reduced in MyD88 KO mice repeatedly exposed to ODE for 7 days, compared with WT animals exposed to ODE (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Organic dust–induced epithelial-cell expression of intercellular adhesion molecule–1 (ICAM-1) is reduced in MyD88 KO mice. Lung sections from WT and MyD88−/− mice, treated for 7 days with saline or ODE, were stained for ICAM-1 (CD54) expression. Representative images show airway epithelial-cell staining of saline-treated WT (A) and saline-treated KO (B) mice, and ODE-treated WT (C) and ODE-treated KO (D) mice, at ×40 magnification. Scale bars represent 60 μm.

Discussion

We report that the TLR/IL-1RI/IL-18R adaptor protein MyD88 is central in mediating the airway inflammatory response to ODE. This MyD88 dependence was demonstrated by a reduction in AHR and a near absence of neutrophil influx and cytokine/chemokine release detected in the BALF after ODE treatments. In addition to the previously described roles for TLR2 and TLR4, our experiments indicated contributory roles for additional MyD88-depdendent receptors, including TLR9 and IL-18R. Interestingly, despite the near absence of airway inflammation in MyD88 KO animals after ODE treatments, lung parenchymal histopathology was significantly increased in MyD88 KO mice, suggesting impairment in the transepithelial migration of inflammatory cells into the airspace of MyD88 KO animals. Collectively, these are the first experiments to establish that the acute organic dust–induced airway response is dependent on MyD88 signaling.

Organic dusts from industrialized, large concentrated animal feeding operations are complex, and this complexity has posed challenges to an understanding of host defense mechanisms. Previous studies demonstrated that endotoxins and peptidoglycans are found within these environments, and that these agents can mediate airway inflammatory consequences (1). Moreover, we and others have reported that mice deficient in TLR2 (7, 14) or TLR4 (7) are partly, but not completely, protected from organic dust–induced airway inflammation. In an effort to better understand the airway response to organic dust, we chose to target MyD88, a downstream adaptor protein common to all TLRs (except TLR3), as well as IL-1R and IL-18R (16). BALF experiments showed the near absence of an airway inflammatory response to organic dusts in MyD88 KO animals, suggesting that the MyD88 pathway is central to the organic dust response. Our experiments also revealed a modest role for TLR9, where only ODE-induced cytokine/chemokine production, but not neutrophil influx, was partly reduced in TLR9-deficient mice (Figure 2). Because TLR9 elicits inflammatory responses upon sensing unmethylated CpG oligodeoxynucleotides from bacteria (1), these findings suggest a role for environmental bacterial DNA in eliciting airway inflammation. The presence of bacterial DNA has been described by others in various agricultural environments (9, 11, 12). Our experiments would support a functional role for bacterial DNA in mediating complex organic dust–induced airway disease. Finally, Charavaryamath and colleagues previously reported a partial role for TLR4 signaling in mediating swine barn air–induced airway inflammation (7). Our experiments, using a different exposure model (i.e., the intranasal inhalation of swine confinement ODE), also demonstrated a partial but not complete reduction in airway inflammatory consequences after organic dust exposure (Figure E1 in the online supplement).

The relative contributions of the IL-1R and IL-18R signaling pathways were next examined, because these members of the IL-1 family also use MyD88 to transduce activation signals (16). However, the IL-1RI signaling pathway does not appear to play a major role in eliciting inflammation after acute organic dust exposure. This observation is consistent with work demonstrating that an endotoxin alone–induced airway inflammatory response is independent of IL-1R (20). In contrast, the IL-18R pathway does appear to affect lung inflammation, because neutrophil influx and neutrophil chemokine production were significantly reduced in IL-18R–deficient mice after ODE treatment. These results differs from those in previous work with endotoxin, wherein IL-18R signaling was not found to be important in the ensuing airway inflammatory response (20). However, the IL-18/IL-18R pathway has been shown to play an important role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary inflammation and emphysema in mice exposed to cigarette smoke (21). The IL-18 pathway has also been associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)–like parenchymal, airway, and vascular remodeling (22). Thus, future investigations may be warranted to determine the importance of the IL-18 pathway in organic dust–induced airway diseases.

Previous studies established that repetitive organic dust exposures result in the formation of peribronchiolar/perivascular and lung aggregates, comprised predominately of T cells but also of B cells (17). In the present study, MyD88-deficient animals displayed an increased proportion of B cells to T cells in the lung parenchyma compared with WT mice at 1 week after ODE treatment. Transient roles for TLRs and MyD88 in B-cell responses have been reported, including germinal-center reactions, class switching, and neutralization and long-term antibody responses against infections (23). Earlier studies reported positive correlations with specific swine antigen concentrations (e.g., swine epithelial antigen and urinary antigen) and specific serum anti-IgG responses in exposed workers, implicating a humoral response (24). In COPD, oligoclonal B cells are increased and organized into lymphoid follicles (25). Although the nature of the antigens eliciting this COPD immune response remains unknown, microbial antigens, cigarette smoke–derived antigens, apoptotic cells, breakdown products from the extracellular matrix, and autoantigens have been suggested (25). Because MyD88 deficiency has been associated with increased lung cell apoptosis after bleomycin lung injury (26), we investigated here whether lung-cell apoptosis was enhanced in MyD88-deficient animals exposed to organic dust, as a potential explanation for the dysregulated inflammatory response. However, no difference in the minimal degree of ODE-induced lung cell apoptosis was evident between MyD88-deficient and WT mice (Figure E1).

The paradoxical observation of a near-absent airway luminal response, with an enhanced lung parenchymal response, to ODE in the setting of MyD88 deficiency was demonstrated, suggestive of an impairment of appropriate transepithelial cell migration. To offer a potential explanation for this observation, ODE-induced neutrophil chemokine production (i.e., CXCL1 and CXCL2) was nearly absent in MyD88 KO mice, implying a disruption in the chemoattractant gradient. In addition, the epithelial expression of the adhesion molecule ICAM-1 was reduced after ODE treatment in MyD88 KO animals (Figure 6). Together, these experiments suggest an important role for MyD88 in airway epithelial cell function in response to organic dust. Others have reported that MyD88 deficiency is associated with early tight-junction disruption and enhanced permeability in intestinal epithelial cells (27). MyD88 deficiency was also recently shown to promote tracheal epithelial-cell metaplasia (28). Of note, ex vivo stimulated lung slices from MyD88 KO mice demonstrated appropriate responses to a MyD88-independent inflammatory agent, phorbol 12–myristate 13–acetate, but not ODE (Figure E2), demonstrating the ability of MyD88-deficient lung cells to respond to non-MyD88–dependent stimuli. Others have also shown that major cellular functions remain intact in MyD88-deficient neutrophils (29).

In conclusion, this study demonstrates several new aspects related to organic dust–induced airway inflammation. Specifically, MyD88 is central to the acute, complex organic dust–induced AHR and airway inflammatory response, and moreover, the upstream receptors TLR9 and IL-18R are added to TLR2 and TLR4 as important contributors to explain this response. Interestingly, MyD88-deficient mice also showed an impaired transepithelial migration of inflammatory cells into the airway lumen, with a resultant increase of lung histopathology marked by increased lymphocytes, and particularly B cells. This observation could evoke renewed interest in measuring the humoral or antibody response in organic dust–exposed workers. Finally, future studies may also be warranted to examine whether known polymorphisms of this MyD88-dependent signaling pathway contribute to airway responses in exposed workers.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jane DeVasure and Elizabeth Klein for technical assistance, and David Wert (Facility Supervisor, Department of Pathology and Microbiology at the Tissue Science Facility of the University of Nebraska Medical Center) for assistance with lung-tissue processing and sectioning, hematoxylin-and-eosin staining, and preparation of the digital microscopy images that illustrate the present study. The authors also thank Lisa Chudomelka for assistance with preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This declaration includes all sources of funding for the research reported in this study. The work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (2R01ES019325 to J.A.P.), the National Institute of Occupational Safety Health (2R01OH008539-01 to D.J.R., and 1U54OH010162-01 to J.A.P. and T.A.W.), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (5R01NS40730 to T.K.) through the national Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0479OC on March 14, 2013

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Poole JA. Farming-associated environmental exposures and effect on atopic diseases. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ege MJ, Mayer M, Normand AC, Genuneit J, Cookson WO, Braun-Fahrlander C, Heederik D, Piarroux R, von Mutius E, Transregio GABRIELA. 22 Study Group: exposure to environmental microorganisms and childhood asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:701–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Senthilselvan A, Beach J, Feddes J, Cherry N, Wenger I. A prospective evaluation of air quality and workers’ health in broiler and layer operations. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:102–107. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.045021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundblad BM, von Scheele I, Palmberg L, Olsson M, Larsson K. Repeated exposure to organic material alters inflammatory and physiological airway responses. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:80–88. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00105308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demanche A, Bonlokke J, Beaulieu MJ, Assayag E, Cormier Y. Swine confinement buildings: effects of airborne particles and settled dust on airway smooth muscles. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2009;16:233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poole JA, Alexis NE, Parks C, MacInnes AK, Gentry-Nielsen MJ, Fey PD, Larsson L, Allen-Gipson D, Von Essen SG, Romberger DJ. Repetitive organic dust exposure in vitro impairs macrophage differentiation and function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charavaryamath C, Juneau V, Suri SS, Janardhan KS, Townsend H, Singh B. Role of Toll-like receptor 4 in lung inflammation following exposure to swine barn air. Exp Lung Res. 2008;34:19–35. doi: 10.1080/01902140701807779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senthilselvan A, Dosman JA, Chenard L, Burch LH, Predicala BZ, Sorowski R, Schneberger D, Hurst T, Kirychuk S, Gerdts V, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 variants reduce airway response in human subjects at high endotoxin levels in a swine facility. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1034–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nehme B, Letourneau V, Forster RJ, Veillette M, Duchaine C. Culture-independent approach of the bacterial bioaerosol diversity in the standard swine confinement buildings, and assessment of the seasonal effect. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:665–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poole JA, Dooley GP, Saito R, Burrell AM, Bailey KL, Romberger DJ, Mehaffy J, Reynolds SJ. Muramic acid, endotoxin, 3-hydroxy fatty acids, and ergosterol content explain monocyte and epithelial cell inflammatory responses to agricultural dusts. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2010;73:684–700. doi: 10.1080/15287390903578539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Letourneau V, Nehme B, Meriaux A, Masse D, Duchaine C. Impact of production systems on swine confinement buildings bioaerosols. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2010;7:94–102. doi: 10.1080/15459620903425642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nehme B, Gilbert Y, Letourneau V, Forster RJ, Veillette M, Villemur R, Duchaine C. Culture-independent characterization of archaeal biodiversity in swine confinement building bioaerosols. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:5445–5450. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00726-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey KL, Poole JA, Mathisen TL, Wyatt TA, Von Essen SG, Romberger DJ. Toll-like receptor 2 is upregulated by hog confinement dust in an IL-6–dependent manner in the airway epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L1049–L1054. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00526.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole JA, Wyatt TA, Kielian T, Oldenburg P, Gleason AM, Bauer A, Golden G, West WW, Sisson JH, Romberger DJ. Toll-like receptor 2 regulates organic dust-induced airway inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:711–719. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0427OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Scheele I, Larsson K, Palmberg L. Budesonide enhances Toll-like receptor 2 expression in activated bronchial epithelial cells. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:493–499. doi: 10.3109/08958370903521216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casanova JL, Abel L, Quintana-Murci L. Human TLRs and IL-1Rs in host defense: natural insights from evolutionary, epidemiological, and clinical genetics. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:447–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poole JA, Wyatt TA, Oldenburg PJ, Elliott MK, West WW, Sisson JH, Von Essen SG, Romberger DJ. Intranasal organic dust exposure–induced airway adaptation response marked by persistent lung inflammation and pathology in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L1085–L1095. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90622.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumagai Y, Akira S. Identification and functions of pattern-recognition receptors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:985–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathisen T, Von Essen SG, Wyatt TA, Romberger DJ. Hog barn dust extract augments lymphocyte adhesion to human airway epithelial cells. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1738–1744. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00384.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Togbe D, Aurore G, Noulin N, Quesniaux VF, Schnyder-Candrian S, Schnyder B, Vasseur V, Akira S, Hoebe K, Beutler B, et al. Nonredundant roles of TIRAP and MyD88 in airway response to endotoxin, independent of TRIF, IL-1 and IL-18 pathways. Lab Invest. 2006;86:1126–1135. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang MJ, Choi JM, Kim BH, Lee CM, Cho WK, Choe G, Kim DH, Lee CG, Elias JA. IL-18 induces emphysema and airway and vascular remodeling via IFN-gamma, IL-17A, and IL-13. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1205–1217. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1545OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakajima T, Owen CA. Interleukin-18: the master regulator driving destructive and remodeling processes in the lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1137–1139. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0590ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerutti A, Puga I, Cols M. Innate control of B cell responses. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crook B, Robertson JF, Glass SA, Botheroyd EM, Lacey J, Topping MD. Airborne dust, ammonia, microorganisms, and antigens in pig confinement houses and the respiratory health of exposed farm workers. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1991;52:271–279. doi: 10.1080/15298669191364721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brusselle GG, Joos GF, Bracke KR. New insights into the immunology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2011;378:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60988-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Mascarenhas MM, Garg HG, Quinn DA, et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med. 2005;11:1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brandl K, Sun L, Neppl C, Siggs OM, Le Gall SM, Tomisato W, Li X, Du X, Maennel DN, Blobel CP, et al. MyD88 signaling in nonhematopoietic cells protects mice against induced colitis by regulating specific EGF receptor ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19967–19972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014669107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giangreco A, Lu L, Mazzatti DJ, Spencer-Dene B, Nye E, Teixeira VH, Janes SM. Myd88 deficiency influences murine tracheal epithelial metaplasia and submucosal gland abundance. J Pathol. 2011;224:190–202. doi: 10.1002/path.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu X, Zhang H, Song Y, Lynch SV, Lowell CA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Caughey GH. Strain-dependent induction of neutrophil histamine production and cell death by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91:275–284. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0711356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]