Abstract

We use a nationally representative survey of Indian households (NFHS-3) to conduct the first study that analyzes whether son preference is associated with girls bearing a larger burden of housework than boys. Housework is a non-negligible part of child labor in which around 60 % of children in our sample are engaged. The preference for male offspring is measured by a mother’s ideal proportion of sons among her offspring. We show that when the ideal proportion increases from 0 to 1, the gap in the time spent on weekly housework for an average girl compared to that of a boy increases by 2.5 h. We conduct several robustness analyses. First, we estimate the main model separately by caste, religion, and family size. Second, we use a two-stage model to look at participation into housework (as well as other types of work) in addition to hours. Third, we use mother’s fertility intentions as an alternative measure of son preference. The analysis confirms that stated differences in male preference translate in de facto differences in girl’s treatment.

Keywords: Son preference, Child labor, Housework, India, National Family Health Survey

Introduction

Besides playing, learning, and socializing with peers, children in less developed countries are frequently involved in a variety of labor activities that are generally referred to as child labor. Some of these activities are geared to the production of marketable outputs, such as working for pay in a factory or helping with farming and selling produce in the market. Others involve the provision of services for family members that are not for market exchange. In this paper we focus on the latter: the household chores children undertake for their families. In particular, this paper analyzes whether son preference is associated with larger gender gaps in the hours of housework children undertake in Indian families. In many societies sons are favored both for cultural or religious reasons and because of their potentially larger future contribution to household income and parental support. As a result, the literature has shown different ways in which girls are discriminated against and receive differentially low human capital investments in health or education, among other things (Pande 2003; Lee 2008; Connelly and Zheng 2003; Mishra et al. 2004). Little research has been done on the role of gender preference in child labor (except for Koolwal 2007), and to our knowledge this is the first study that examines the ramification of son preference for children’s housework. Understanding the role parental attitudes play in children’s time and gender disparities of time allocation should be of great interest both for academic and policy reasons.

Housework is a non-negligible part of child labor in which approximately 60 % of children in our sample are engaged. In fact, recent research has adopted a more generous definition of child labor to include household chores (Kurosaki et al. 2006; Edmonds 2006; Basu et al. 2009). Helping with chores is an integral part of children’s life in many parts of the world (Zelizer 1985; Montgomery 2009), perhaps the most common form of labor provided by children. Pooling the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) data of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) for over 30 developing and under-developed countries, Edmonds (2009) shows that children aged 10–14 spend more time on household labor than in market-oriented work. Ignoring household labor would “frequently understate total hours worked by a child by a factor slightly>2” (Edmonds 2009, p. 15). Edmonds (2009) shows that children who are heavily involved in market work (e.g.,>12 h per week) tend to perform a few additional hours of domestic chores, but not vice versa. Despite its prevalence, housework has been an elusive area in the study of child work since most of the previous studies focus exclusively on market-oriented activities (e.g., wage employment) or production for the household’s own consumption (e.g., farm labor).

In this paper we use the National Family Health Survey of India, 2005–2006 (NFHS-3), a nationally representative sample of Indian households, to examine the relationship between son preference (SP) and the level of children’s housework. India is a relevant case since child labor remains common (Basu et al. 2003, 2009) and a preference for sons still prevails with varying intensity across society (Das Gupta et al. 2003; Chung and Das Gupta 2007; Bhat and Zavier 2003; Jayaraman et al. 2009; Gaudin 2011). Worldwide, girls have traditionally performed more household tasks than boys, but in this paper we hypothesize that this gap grows with son preference, as parents reduce boys’ burden of household chores. We construct a measure of son preference based on mother’s ideal proportion of sons (Clark 2000; Koolwal 2007; Lin 2009). To test our hypothesis, we use both OLS and random-effects models of hours of housework for all children and run a set of robustness test to see how the results vary across family size, religion, cast, and specification of the SP variable. Son preference in all these models is correlated with an increase in girls’ relative burden of housework of around 2.5 h per week. Next, we implement a two-stage model to take into account participation in housework and also on other types of work, separately. Finally, we use intended fertility as an alternative way to measure son preference in a restricted sample of families that have one boy and one girl.

Section “Conceptual Framework” presents the conceptual framework of our hypothesis. The description of the data and the construction of the index are included in “Data and Variables.” Section “Empirical Analysis” presents all of the different analyses and “Discussion and Conclusion” concludes with a brief discussion of the implications of results and possible extensions.

Conceptual Framework

In societies where boys are preferred over girls, the literature has shown ways in which girls are discriminated against, such as through excess female infant mortality due to neglect and malnutrition (Das Gupta 1987; Kishor 1993; Rosenblum 2013) and differentially lower human capital investments in health (Pande 2003) or education, among other things (Lee 2008; Connelly and Zheng 2003; Mishra et al. 2004). No research has been done on the role of gender preference in housework, the most prevalent form of child labor. India is a relevant case to use for this analysis since both child labor (Basu et al. 2003, 2009) and son preference remain relatively common (Das Gupta et al. 2003; Bhat and Zavier 2003; Jayaraman et al. 2009).

In many Indian households, it is customary that children help with farming or the family business, or engage in domestic chores (such as cooking and fetching water) for three main reasons.1 First, over two-thirds of the population still live in rural areas and many households lack sufficient infrastructure such as running water (International Institute for Population Sciences 2007; World Bank 2012). Families need to spend additional time to maintain the basic functioning of daily life, and children with appropriate physical strength become involved in many of these chores as they grow up (such as washing clothes or fetching water). Second, the Indian workforce remains largely agricultural, nearly 50 % in 2009 (Ministry of Labor and Employment, Government of India 2010). Agricultural production in India is labor-intensive and dominated by small holders (Edmonds 2003; Birthal et al. 2007); thus, children become the natural helpers when farming requires more labor input. Third, despite rapid economic growth since 2000, the distribution of income and wealth has remained highly unequal; a large proportion of Indians still live below the country’s poverty line (World Bank 2012). Because of poverty or near-poverty, children may need to engage in economic activities (helping with farming or family business) to ensure family survival (Basu and Van 1998) and since household appliances (e.g., washer, stove) may not be affordable to many families, children’s manual labor must substitute instead.

Definitions of “children’s work” or “child labor” are not uniform in the literature. Earlier literature (e.g., Basu and Van 1998) defined “work” or “child labor” as activities that strictly resulted in marketable outputs, such as wage employment or helping with family business. Lately research papers have adopted a more liberal definition which also includes household chores (e.g., Kurosaki et al. 2006; Edmonds 2006; Basu et al. 2009). This broader definition seems to be a better choice in assessing how children’s welfare is influenced by different types of activities. For example, in assessing how labor influences schooling, there is no reason to define “work” as market work exclusively, because children cannot study when they are engaged in housework even if it does not generate marketable outputs. Also, there is little evidence suggesting that one type of work is more “benign” or “harmful” to children than other types of work. Last but not the least, excluding housework as a part of the definition of child labor would grossly underestimate the burden on girls; worldwide, girls perform more housework than boys (Edmonds 2009).

A number of microeconomic studies have examined factors associated with children’s work in South Asia, including household wealth (Basu et al. 2009), siblings’ contribution/substitution (Edmonds 2006), exogenous shocks such as trade reform (Edmonds and Pavcnik 2005), mothers’ education (Kurosaki et al. 2006), and mother’s labor force participation (Self 2011). Other research has investigated the extent to which children’s work and schooling are substitutes, including Hazarika and Bedi (2006), or Kurosaki et al. (2006). Few studies have focused exclusively on housework as the outcome variable, except for Webbink et al. (2011). Webbink et al. (2011) examined factors associated with housework performed by children in 16 developing countries, including India. They used the mean difference in age between a husband and wife and the proportion of married women living with the husband’s original family to indicate “traditionalism” of an area. Interestingly, these two variables are significantly associated with housework only among boys but not girls in Asia. We pursue this line of analysis here. We focus, however, on how son preference mediates the intra-household allocation of children’s chores to boys versus girls.

In many societies sons are favored over daughters for a variety of social, economic, and religious reasons (Arnold et al. 1998; Das Gupta et al. 2003; Pande and Astone 2007). There are two primary determinants of the differential treatment of men and women in these cultures. The first is related to cultural or religious traditions (Arnold et al. 1998; Chakraborty and Kim 2010). Since many of these societies are patrilineal, only men can continue the family lineage, and daughters after marriage traditionally move in with their husband’s family. Also, men or sons play unique roles in many religions. For example, according to Hindu tradition, sons are “needed for cremation of the deceased parents, because only sons can light the funeral pyre” (Arnold et al. 1998, p. 301). Bhat and Zavier (2003) show how, in India, Hindus and particularly Sikhs display the highest levels of son preference. Similarly, across castes, the behavior of those that have achieved high ritual status (“Sanskritized”) usually conforms to male preference with regard to dowry, and marriage, among other things (Chakraborty and Kim 2010). Lately, families of lower castes with high economic resources have also imitated those behaviors that reflect son preference (Agnihotri 2000; Gaudin 2011).

The second reason is related to the instrumental value of sons, or more broadly, to socio-economic consequences of the male dominance in many areas of a society. Sons (or men) may have higher earning potential and may be perceived as better providers of old-age support to parents than daughters (or women). In agricultural societies, sons are an important source of labor for family farming. Labor market opportunities for women remain more constrained worldwide than men’s in most countries regardless of their development stage (Rosenzweig and Schultz 1982; Kishor 1993; Berik and Biglinsoy 2000; Bhattacharya 2005).

If parents are interested in eventually realizing (and, potentially, benefiting from) the value of a son, they need to invest in their sons’ human capital. Doing housework contributes little to sons’ human capital buildup. Thus, parents would rather have sons engaged in education or other training activities (such as acquiring skills from family businesses) that are expected to help to generate income for the family in the future. An implication of this claim is that children with higher earning potential will be treated more favorably and receive more family resources (Rosenzweig and Schultz 1982). This may take the form of better quality of care, more time of play and leisure, and potentially fewer household chores. On the assumption that excessive housework is unhealthy, parents will refrain from assigning much housework to sons in order to maintain their health capital. Sons’ health is instrumental to higher earnings in the future, and to greater assistance to parents as they age, and to continuation of the family lineage.

Accordingly in those societies that display son preference, a daughter is not expected to be the primary source of old-age supports, regardless of prior parental investments. In patrilineal societies, a daughter is expected to leave her biological family once she is married, and to typically assume the responsibility of caring for the husband’s family (Das Gupta et al. 2003). The expected loss of daughters after marriage further reduces the incentives of parents to involve daughters in education or in other long-term investments. Helping with daily chores is a way parents ask daughters to contribute to the family.

Of course a relatively higher burden of housework among girls may simply result from parents’ belief that a girl should be good at housework skills in order to be socially fit once she enters adulthood. Those gender role attitudes are closely related to both son preference and the division of housework, generally viewed as a woman’s realm. Naturally, “gender role” ideology also influences the demand for sons. If parents strongly believe that the best role women can play is homemakers but not breadwinners, they may prefer to have more sons to ensure old-age support. However, it is important to note that gender role ideology is not a synonym for son preference: a mother may have no differential preference on the gender of her offspring, while she still insists that girls should learn housekeeping to be socially fit. Because of its strong linkage with son preference (Shu 2004) and gender division of housework (Coltrane 2000), in robustness analysis we explore the role of media exposure as a proxy for gender role orientation.

Finally, it should be clear from the previous discussion that preference for sons does not result from a “taste for discrimination” against girls (Folbre 1984). An excessive amount of housework may be unhealthy for both boys and girls, but there is no evidence suggesting that parents welcome daughters’ housework burden on their time and health while opposing housework assignments to sons. The preference for sons does not result from parents benefiting from daughters’ disutility, but rather from their lower earning potential or their secondary status in patrilineal family systems (Das Gupta et al. 2003).

As a result of all the different considerations of how parents perceive the instrumental values of sons discussed in this section, we expect a greater gender difference in time spent on housework among children in families that display strong son preference than in those where there is no such preference (or where there even is a “daughter preference”).

Data and Variables

We use the National Family Health Survey of India, 2005–2006 (NFHS-3), a survey administered to a nationally representative sample of Indian households, which follows the structure of the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). NFHS-3 collected information from 109,041 households within over 3,000 primary sample units (PSU)—villages in rural areas and census blocks in cities—across all Indian states. In each household, individual interviews were conducted among all men and women aged 15–49 regardless of their marital status. A total of 124,385 eligible women were interviewed and asked about their fertility preferences, among other things. In addition to the basic demographic characteristics, more extensive information was also provided about children aged 6–14 in the household. Given the structure of the survey and our research questions, the units of analysis in this paper are children aged 6–14 who live in the same household with their mothers. Our sample includes a total of 85,831 children, born to 46,070 eligible women. Mothers in our sample have on average 3.3 children, although only 1.9 children with complete interviews, because many of their children fall outside the 6–14 age range.

The outcome variable is mother-reported hours of housework performed by her children during the survey week, as recorded in the “Child Labor Module” of the survey. Housework refers to tasks that are necessary to maintain the functioning of a family, but are not intended for market exchange nor involve any payment for performance. In this study, we use the terms “housework,” “household chores,” or “household labor” interchangeably. Examples of housework include cleaning, shopping, collecting firewood, or caring for younger children. The original wording of the relevant questions in the survey is as follows: (1) “during the past week, did (name) help with household chores, such as shopping, collecting firewood, cleaning, fetching water, or caring for children?” (If yes, go on to the next question). (2) “Since last (day of the week), about how many hours did he/she spend doing these chores?”

The module that the NFHS-3 adopted in this survey was synchronized with and is similar to that of UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (UNICEF 2011), widely used by researchers who study child labor worldwide. Note that unpaid work in farm labor or helping with a family business does not count as housework by UNICEF’s or in the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS). Consistent with general patterns found by previous research (see Edmonds 2007 for a review), the majority of children’s labor input in India took the form of domestic work; <15 % of Indian children were involved in market work, including working for household or non-household members. In the distribution of hours of housework during the survey week, there is a cluster of responses at 0 h for about 50 % of the boys and close to 40 % of the girls. To address this issue, in the empirical section we will study both the intensive and the extensive margin of housework. Further to address the right-skewedness of the distribution, we will use a lognormal model in the statistical analysis. Finally, the data exhibit evidence of heaping, with a systematic pattern of clustering at multiples of seven, presumably because people tend to report the hours of work per week by multiplying the hours per day by seven. This is not unusual in self-reported hours of work and, as long as there is no bias in clustering, the point estimators will remain unbiased, although with a larger standard deviation. Results in the paper are robust to running the analyses separately only for those clustering hours.

Son Preference

Our predictor variable of interest is the extent of son preference of the mother. In this paper we measure it by the ideal proportion of sons calculated with the method employed in Clark (2000), Koolwal (2007) and Lin (2009), among others. We use information from the following two separate questions on fertility preferences included in the survey to construct it.

“If you could go back to the time you did not have any children, and you could choose exactly the number of children to have in your whole life, what number would that be?”

“How many of these children would you like to be boys? How many would you like to be girls? For how many would gender not matter?”

From these two questions we obtain three numbers: (1) the ideal number of sons, (2) the ideal number of girls, and (3) the number of children whose gender would not matter to mothers. Then the ideal proportion of sons is calculated as

For a woman desiring more sons than daughters this measure is >0.5 and suggests a preference for sons. For any child whose mother states that “sex doesn’t matter,” we assign an equal weight of 0.5 to the number of desired sons and daughters. Thus, if a woman feels indifferent about the sex of all her children, her “son preference index” (SP) is 0.5, regardless of her total desired number of children. This method represents an improvement over simply calculating the share of sons in the ideal family size by taking the number of sons wanted over the total number of children, as done in Bhat and Zavier (2003). It allows for a larger dispersion of the measure of son preference and discriminates over different family structures and preferences on the number of girls. In that regard, our index of son preference has similar advantages as the SP measure employed by Gaudin (2011), namely the difference between ideal number of boys and ideal number of girls divided by the ideal family size. It is noteworthy that in the NFSH-3 survey a significant minority (13.7 %) of the women explicitly state that her children’s sex does not matter. In the distribution of the SP index there are large clusters at 0.5 (preference for balanced gender distribution) and 0.67 (when two-thirds of the children are sons) with, respectively, 68 and 22 % of the responses at those values in the weighted sample. Around 2.5 % of the respondents express some extent of girl preference (SP < 0.5). For some of the analyses, we create a dummy variable that equals one for those who express son preference (who account for 29.5 % of the sample) and pool together those who prefer more daughters (i.e., ideal proportion < 0.5) and those who prefer a balanced composition (i.e., ideal proportion = 0.5) in the reference group.2

A natural concern with these measures as with any measure that uses subjective answers from individuals is that the subjects may provide a socially desirable answer instead of their true preference when asked about their ideal sex composition for children. For example, a well-educated woman with strong son preference may claim that she desires one boy and one girl, even if in fact she wants all her children to be boys. This kind of bias is inherent to the question. However, it is difficult to measure what types of women are more likely to misreport preferences (e.g., either mothers with high education or those with low education). In addition, these measures are exposed to the risk of ex-post rationalization when women’s answers are affected by the current composition of their offspring. An extensive literature notes that the concern of rationalization can be addressed by introducing appropriate controls in the models as we do (Bhat and Zavier 2003; Pande and Astone 2007; Gaudin 2011). In “Measuring Son Preference with Fertility Intention” we supplement the main analysis that employs SP as defined here with another variable that indicates whether women who already have two children desire additional children. This measure based on fertility intention is likely less subject to women’s intentional misreporting or ex-post rationalization than the ideal proportion of sons (Bankole and Westoff 1998).

Control Variables

Our models include a large set of control variables. First, we add several interaction terms among children’s sex, place of residence, and age. We do so to control for the fact that there are urban–rural and gender divides in hours spent on household chores and those gaps widen as children grow older. In general, at any given age, girls in rural areas spend the most hours on housework, followed by girls in urban areas, boys in rural areas, and finally boys in urban areas.

Further we use available information regarding whether a child has ever attended school in the previous year, as well as the time in the survey week that a child spent on market-oriented work and farming, for both family members and non-family members separately. Although we expect these activities to be negatively associated with the level of housework children undertake, the literature notes that it is unclear whether these activities are real substitutes among themselves or whether, in many instances, they occur simultaneously (Edmonds 2007). Wealth measures, the number of brothers and sisters, and the number of family members are also included in the questionnaire. We expect the need of housework to be positively associated with the size of the family and negatively associated with improving material conditions (Basu and Van 1998). We use the survey’s wealth index to represent household material conditions, and rescale it by dividing by 10,000. The wealth index, ranging from –18 to 24, is generated directly by NFHS using factor analysis calculated over the full sample of households and its units have no direct interpretation. We control for whether the family is Muslim to take into account their traditionally larger family sizes and to analyze whether the impact of son preference on unequal treatment of boys and girls is different for this group. Following original research by Dyson and Moore (1983) we create a variable North that combines families living in Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh (including Delhi), Rajasthan, and Gujarat.3 Son preference is particularly strong in Northern India and we are interested to see whether our findings prevail once we control for this regional difference (Miller 1981; Arnold et al. 1998; Dyson and Moore 1983; Bhat and Zavier 2003). Finally, all models include a set of state-level measures: GDP per capita, infant mortality, and population density.

Descriptive Analysis

The first rows of Table 1 present descriptive statistics of the variables included at the family level, comprising fertility preferences of the mother, parents’ characteristics, and other family background characteristics. Regarding our main variable of interest, the mean desired proportion of sons, 0.56 indicates a moderate level of preference for sons over daughters: the average woman wants slightly more than half of her children to be male.

Table 1.

Summary statistics, family and child level (NFHS-3, 2005)

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Obs. | Weighted N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family level | ||||||

| Son preference (ideal proportion of sons) | 0.56 | 0.12 | 0 | 1 | 44,349 | 47,168 |

| Mother’s education (in years) | 3.5 | 4.5 | 0 | 23 | 46,066 | 48,851 |

| Indifferent about children’s sex | 0.14 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 | 44,786 | 47,638 |

| Mother’s age | 33.6 | 5.9 | 18 | 49 | 46,070 | 48,853 |

| Father’s education (in years) | 6 | 5 | 0 | 24 | 45,630 | 48,405 |

| Number in household | 6.3 | 2.9 | 2 | 35 | 46,070 | 48,853 |

| Number of living children | 3.4 | 1.5 | 1 | 15 | 46,070 | 48,853 |

| Wealth index (scaled) | −3.5 | 9.2 | −18 | 24 | 46,070 | 48,853 |

| Household head is Muslim | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 | 46,070 | 48,853 |

| Exposure to media | 5.8 | 5.5 | 0 | 21 | 46,011 | 48,789 |

| Living in rural area | 0.7 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 | 46,070 | 48,853 |

| North | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | 46,070 | 48,853 |

| State-level GDP p.c. (rupee) | 25,480 | 11,368 | 8,151 | 85,299 | 46,070 | 48,853 |

| State infant mortality rate | 56 | 16 | 13 | 76 | 46,070 | 48,853 |

| Population density (people/km2) | 620 | 1,066 | 15 | 10,319 | 46,070 | 48,853 |

| Child level | ||||||

| Age | 9.8 | 2.5 | 6 | 14 | 85,831 | 92,968 |

| Girl | 0.48 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 85,831 | 92,968 |

| Number of sisters | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0 | 9 | 85,831 | 92,968 |

| Number of brothers | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0 | 9 | 85,831 | 92,968 |

| Number of siblings aged 5 or under | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0 | 4 | 85,831 | 92,968 |

| Number of elder sisters | 0.8 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 85,831 | 92,968 |

| Number of younger brother | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0 | 6 | 85,831 | 92,968 |

| Ever attended school in 2005 | 0.79 | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 85,683 | 92,837 |

| Helped with household chores | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 85,285 | 92,472 |

| Hours spent on household chores, among those who helped | 9.6 | 8.1 | 0.5 | 95 | 48,130 | 55,011 |

| Hours spent on household chores, all children | 5.7 | 7.9 | 0 | 95 | 85,258 | 92,455 |

| Worked for household members | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0 | 1 | 85,228 | 92,437 |

| Hours worked for household members, all children | 0.9 | 4.7 | 0 | 95 | 85,208 | 92,414 |

| Worked for non-household members | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0 | 2 | 85,342 | 92,517 |

| Hours worked on non-household members, all children | 0.9 | 5.8 | 0 | 95 | 85,267 | 92,435 |

Most families (70.5 %) live in rural areas, a third of them live in the North and the head of the household is Muslim in only 14.8 % of them. These figures are slightly higher but quite close to the national profiles in 2005 (International Institute for Population Sciences 2007). The high share of rural families accounts for both the large number of individuals (6.3) and large number of children (3.4) in the household. The average educational attainment of parents is not high: 3.5 years of schooling for mothers and 6.0 years for fathers. Further, only 35–40 % of the mothers are literate. The variation in all state-level characteristics is substantial.

In the second part of Table 1 we include variables regarding children’s characteristics, including age, sex, school attendance, and whether and how long they have participated in different types of work during the survey week. Slightly more than half (51.8 %) of these children are boys, and the average age of the sample children is 10. Most (79.4 %) of the children had some schooling in 2005, although the survey did not inquire whether the children attended school regularly.

The majority (59.5 %) of children helped their families with household chores during the survey week; <7.2 % worked for non-household members and <7.4 % worked with household members on activities such as farm labor, family business, or street vending. The high prevalence of household labor and the low frequency of market work—either working for household or non-household members—are consistent with the pattern reported in other child labor research. Among those who helped their families with housework, on average they provided 9.6 h of household labor per week. For the entire sample, the average hours spent on household chores is 5.7 h. The average number of hours worked for non-household members as well as for household members for all children is only 0.9 per week.

We start by examining a basic cross-tabulation between son preference and children’s housework labor during the survey week. Consistent with our hypothesis, the gap in the time spent on housework between a boy and a girl increases substantially with son preference. When the ideal proportion is zero, boys actually do a bit more housework than girls. But as son preference increases, girls do increasingly more housework. The difference between girls and boys in hours of housework grows to 2.66 h on average among those with SP between 0 and 0.5, and to 3.81 h among those with SP over 0.5 (both significant at the 0.001 level). In addition, total hours of housework performed (the work of boys and girls combined) are larger as the measure of son preference increases. Since son preference is likely endogenous, it is bound to be jointly determined with other household decisions. The observed increase in hours of housework is likely associated with wealth and urban-rural differences in the demand for housework. Families in rural areas tend to have worse material conditions and require more housework labor for their daily activities than those in urban areas, both of which are associated with an increase in overall hours of housework performed by children. Similarly, these families tend to report a stronger preference for male offspring. We expect that some of the observed differences will be less pronounced as we control for wealth and rural residence in the statistical analysis.

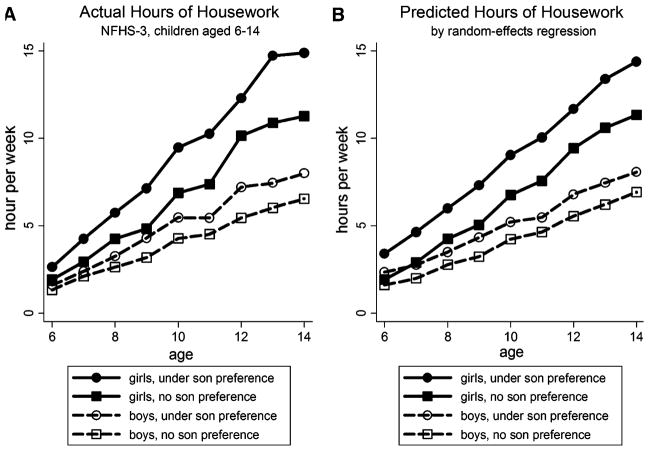

We suspect that the manifestation of son preference is more explicit as children get older, since older children can undertake more physically strenuous tasks. To explore this idea, the left hand side of Fig. 1 plots at each age the average hours of housework during the survey week, broken down by children’s sex and level of son preference expressed by the mother (with either SP > 0.5 or SP ≤ 0.5). Figure 1 shows that at any given age, girls (the two solid lines) spend more time on housework than boys (the two dash lines). Furthermore, the boy-girl difference, within-girl difference (between those in households with son preference and the others), and within-boy difference (between those in households with son preference and the rest) grow largely in proportion to age. Thus, a model that focuses on proportional change (such as a log-normal model) may be appropriate to examine the relationship between son preference and hours in housework. For both boys and girls, son preference is associated with more hours of housework, but girls perform proportionally more additional hours than boys under son preference. This pattern is consistent with the fact that the increase in housework among girls is substantially greater than boys’ as the ideal proportion of sons grows from zero to one.

Fig. 1.

Actual and projected weekly hours of housework, by children’s sex, age, and son preference. Estimates used in the predictions employ the dichotomous definition of son preference (SP = 1 if SP >0.5). Estimates are available upon request. Source NFHS-3, 2005

Empirical Analysis

Basic Models of Hours of Housework

To investigate the effect of parental son preference on children’s housework, we start with basic OLS estimates of the following model.

where Yhij represents hours of housework performed by child j in family i in PSU h, SP is our index of son preference, Girl refers to the gender of the child, X is a vector of control variables, and uhij is the error term. Our hypothesis states that the gap between the hours a girl spends on housework over boys’ grows with son preference. The change in the difference between hours of work of girls over boys is captured by the interaction term, b2. In the models presented in this section we use both specifications of son preference described in “Data and Variables” either a continuous scale or an indicator for whether the desired proportion of sons is strictly > 0.5.

Table 2, columns (1)–(4), displays OLS estimates of hours of housework undertaken by children aged 6–14 using a continuous index of SP. The model in column (1), which includes only the three basic variables indicate that SP is associated with more hours of housework and that girls in families with a higher index of SP also undertake a relatively higher load than boys: around 4.2 h more per week for families with a SP equal to one compared to those with SP equal to zero. Column (2) includes a set of interactions among the gender, age, and place of residence of the child. In the following column, an additional set of covariates controls for the child’s school attendance and hours employed in other forms of work as well as family composition, religion, wealth, and parental education. Column (4) presents the most complete specification, which also encompasses state characteristics and controls for North India and its interaction with the gender of the child. As more covariates are added into the model, the coefficient for the interaction between SP and Girl decreases somewhat in size but remains highly significant at p < 0.1. Consistent with the hypothesis, results in column (4) indicate that after the child, family and geographic controls are included; the gap in time devoted to housework between girls and boys is 2.65 h larger in families with high son preference than in those with strong daughter preference.

Table 2.

Son preference and children’s weekly hours of housework in India, OLS and linear random-effects regressions

| Variables | (1) OLS |

(2) OLS |

(3) OLS |

(4) OLS |

(5) Random effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girl | 0.202 (0.255) | −1.901*** (0.250) | −1.862*** (0.247) | −1.779*** (0.245) | −1.735*** (0.233) |

| Son preference (SP) | 1.553*** (0.265) | 0.978*** (0.260) | −0.128 (0.260) | −0.407 (0.259) | −0.821*** (0.272) |

| SP * Girl | 4.246*** (0.463) | 3.770*** (0.439) | 3.110*** (0.431) | 2.654*** (0.428) | 2.520*** (0.362) |

| Age | 0.511*** (0.016) | 0.537*** (0.017) | 0.529*** (0.017) | 0.593*** (0.020) | |

| Age * Girl | 0.457*** (0.027) | 0.481*** (0.027) | 0.483*** (0.027) | 0.494*** (0.027) | |

| Rural * Girl | 0.447*** (0.138) | 0.496*** (0.137) | 0.474*** (0.136) | 0.414** (0.165) | |

| Rural | 0.369*** (0.085) | −0.900*** (0.094) | −0.847*** (0.093) | −0.720*** (0.150) | |

| Rural * Age | 0.273*** (0.024) | 0.235*** (0.024) | 0.245*** (0.024) | 0.267*** (0.025) | |

| Rural * Age * Girl | 0.132*** (0.040) | 0.123*** (0.039) | 0.129*** (0.038) | 0.150*** (0.035) | |

| Ever attended school 2005 | −1.303*** (0.091) | −1.199*** (0.091) | −1.012*** (0.067) | ||

| Hours worked for hh members | 0.213*** (0.016) | 0.211*** (0.017) | 0.170*** (0.006) | ||

| Hours worked for non-hh members | 0.012 (0.008) | 0.012 (0.008) | −0.011** (0.004) | ||

| Number of sisters | 0.130*** (0.031) | 0.058* (0.031) | −0.013 (0.027) | ||

| Number of brothers | 0.430*** (0.035) | 0.296*** (0.035) | 0.196*** (0.032) | ||

| Indifferent about children’s sex | −0.017 (0.083) | −0.016 (0.082) | 0.068 (0.082) | ||

| Ideal # of children ≥4 | 0.372*** (0.090) | 0.569*** (0.090) | 0.388*** (0.082) | ||

| Mother’s age | −0.045*** (0.006) | −0.038*** (0.006) | −0.047*** (0.006) | ||

| Mother’s education | −0.074*** (0.009) | −0.040*** (0.009) | −0.028*** (0.009) | ||

| Father’s education | 0.031*** (0.008) | 0.007 (0.008) | −0.011 (0.008) | ||

| Number of family members | −0.007 (0.011) | −0.033*** (0.011) | −0.051*** (0.011) | ||

| Wealth index | −0.075*** (0.005) | −0.068*** (0.005) | −0.066*** (0.005) | ||

| Muslim | −1.045*** (0.095) | −1.028*** (0.094) | −0.731*** (0.119) | ||

| Muslim * Girl | 0.602*** (0.140) | 0.566*** (0.138) | 0.576*** (0.120) | ||

| GDP per capita (10,000 rupee) (state) | −0.285*** (0.028) | −0.291*** (0.042) | |||

| Pop density (1,000 people/km2) (state) | 0.179*** (0.021) | 0.144*** (0.034) | |||

| Infant mortality rate (state) | 0.020*** (0.002) | 0.018*** (0.003) | |||

| North India | 0.522*** (0.088) | 0.870*** (0.138) | |||

| North India * Girl | 0.758*** (0.112) | 0.703*** (0.097) | |||

| Constant | 3.016*** (0.151) | 0.544*** (0.148) | 3.038*** (0.208) | 2.733*** (0.259) | 3.512*** (0.063) |

| ln(SD(PSU level)) | 1.034*** (0.016) | ||||

| ln(SD(family level)) | 1.112*** (0.014) | ||||

| ln(SD(residual)) | 1.850*** (0.003) | ||||

| Observations | 81,707 | 81,707 | 80,657 | 80,657 | 81,707 |

| Number of groups | 3,847 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.030 | 0.150 | 0.197 | 0.208 |

OLS estimates in columns (1)–(4) and random-effects model in column (5)

Robust standard errors in parentheses

p <0.01;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.1

In column (5) we estimate the most complete specification in column (4) with a random-effects regression (xtmixed procedure in Stata 11), as frequently done by labor economists when analyzing hours of work (e.g., Lundberg and Rose 2000), to study how sensitive our results are to alternative methods. We consider a three-level hierarchy formulation, including children, family, and primary sampling unit (PSU) and redefine the error term in our model as follows uhij = ph + ahi + ehij, where ph are the random effects at the PSU level, ahi are random effects at the family level, and ehij is the error term. Measurements within the same family may be correlated because of shared family environments, and measurements within the same PSU may be correlated due to common social customs. The random-effects model, however, assumes multivariate normality (Teachman et al. 2001), a condition rarely met in most empirical data. It also imposes the strong assumption that the family and PSU specific effects are uncorrelated with the other covariates in the model. Still, the significant coefficient of 2.52 for the interaction of SP and Girl in column (5) is in line with OLS results. In column (1) of Table 3 we run the same random-effects model with the binary definition of son preference. The estimated coefficient implies that son preference (SP > 0.5) is associated with a 0.86 h increase in the gender gap. The magnitudes of random effects are appreciable in both models, indicating a high level of between-family and between-PSU heterogeneity (or within-family and within-PSU correlation). Further, these findings are robust to alternative methods, including negative binomial regression and zero-inflated negative binomial regression (available from authors).

Table 3.

Son preference and children’s weekly hours of housework in India: robustness analysis

| Variables | (1) SP = 1 if SP > 0.5 |

(2) No Educ. |

(3) Child 0–5 |

(4) SP * Age |

(5) Caste |

(6) Muslim |

(7) Non-Muslim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girl | −0.548*** (0.135) | −1.787*** (0.233) | −1.720*** (0.233) | −0.354 (0.370) | −1.810*** (0.259) | −1.319** (0.618) | −1.599*** (0.252) |

| Son preference (SP) | −0.833*** (0.272) | −0.699*** (0.271) | −1.300*** (0.454) | −0.968*** (0.312) | 0.428 (0.778) | −0.912*** (0.291) | |

| SP * Girl | 2.565*** (0.362) | 2.471*** (0.361) | −0.094 (0.646) | 3.040*** (0.410) | 0.918 (1.009) | 2.796*** (0.387) | |

| Son preference (=1 if SP > 0.5) | −0.160** (0.081) | ||||||

| SP (=1 if SP >0.5) * Girl | 0.862*** (0.099) | ||||||

| Ever attended school 2005 | −1.005*** (0.066) | −0.987*** (0.066) | −1.005*** (0.066) | −1.005*** (0.066) | −1.213*** (0.148) | −0.957*** (0.075) | |

| Number of sisters | −0.014 (0.027) | −0.010 (0.027) | −0.013 (0.027) | −0.013 (0.027) | −0.091 (0.060) | 0.007 (0.031) | |

| Number of brothers | 0.187*** (0.032) | 0.207*** (0.032) | 0.196*** (0.032) | 0.195*** (0.032) | 0.203*** (0.066) | 0.198*** (0.037) | |

| # of siblings under age 5 | 0.584*** (0.041) | ||||||

| High caste | −0.232 (0.354) | ||||||

| High caste * Girl | 0.732 (0.483) | ||||||

| High caste * SP | 0.722 (0.615) | ||||||

| High caste * Girl * SP | −2.644*** (0.864) | ||||||

| Age * SP | 0.133 (0.095) | ||||||

| Age * Girl * SP | 0.683*** (0.140) | ||||||

| Constant | 2.550*** (0.282) | 2.391*** (0.318) | 2.104*** (0.324) | 3.246*** (0.376) | 3.008*** (0.331) | 0.210 (0.803) | 3.093*** (0.340) |

| Observations | 80,657 | 80,768 | 80,657 | 80,657 | 80,653 | 12,885 | 67,772 |

| Number of groups | 3,847 | 3,847 | 3,847 | 3,847 | 3,847 | 1,127 | 3,690 |

Random-effects estimates that include all mother and children’s characteristics, state characteristic, and regional and religious controls as in column (5) of Table 2

Robust standard errors in parentheses

p <0.01;

p <0.05;

p <0.1

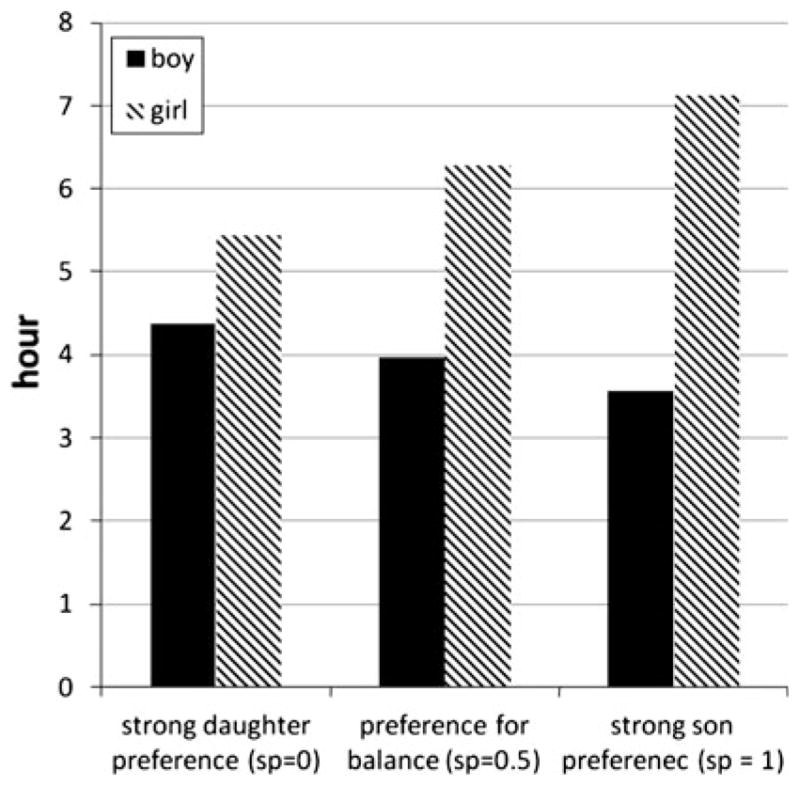

To better visualize the implied association between son preference and housework, we predict the hours of housework for each child based on the random-effects model in column (5) of Table 2, with covariates set at their observed values and random effects at zero. Then we aggregate the hours of housework by children’s sex and level of son preference. Figure 2 clearly shows that son preference is associated with a relative greater burden of housework for girls. It also indicates another interesting pattern: the total hours of housework, for boys and girls combined, increases with the level of son preference, although the gap is not as pronounced as in the simple cross-tabulation comparison where household material conditions or rural residence are not controlled for. Furthermore, the change in the difference in the time spent on housework comes largely from girls’ increasing housework input. As Fig. 2 illustrates, when the ideal proportion for sons grows from 0 to 1, the time an average girl spends on housework increases by 1.7 h (from 5.4 to 7.1), but the hours for boys decrease only by 0.8 h (from 4.4 to 3.55). One post-hoc explanation for the additional hours among girls is that families with a preference for sons adhere more to traditional gender roles, tend to live more in rural areas, and consider it essential for females to be skillful in housework. Thus, to train their daughters to be “socially fit,” parents in these families tend to involve girls in additional household responsibilities, regardless of household material conditions. Predictions using estimates of column (1) in Table 3 produce the same pattern: boys in families with son preference (SP > 0.5) work 0.15 fewer weekly hours of in the house than those living in families with no son preference, whereas girls work around 0.7 more hours.

Fig. 2.

Predicted weekly hours of housework by son preference and children’s sex. Predictions based on column (5) in Table 2 using a continuous variable to measure SP. Source NFHS-3, 2005

With regard to the additional covariates, the results underscore the importance of jointly considering children’s age, sex, and whether they live in rural or urban areas. Consistent with descriptive statistics, older children perform more housework; the coefficient for children’s age is around 0.5 and highly significant (p < 0.001). The coefficient for Girl is negative, primarily because of three large interaction effects: (a) the large and significant interaction coefficient of Girl with age, around 0.49, (b) of Girl and with rural residence, around 0.41, and (c) for the coefficient for the three-way interaction among age, sex, and rural areas, around 0.15 (all at p < 0.001). Similarly, the main effect of rural areas becomes negative once child and family characteristics are included. Taken together, these interactions suggest that the burden of housework is the greatest among girls in rural areas and that both the urban–rural and gender gap in housework grows with children’s age.

Overall, the estimated coefficients for family characteristics are slightly smaller in the random-effects models than in OLS and fall within expectations. Children perform fewer household chores in families with better material conditions, if they have attended school in 2005, or if they have a better educated mother. To address the concern that school attendance is potentially jointly determined with hours of work and that this may affect our estimate, in column (2) of Table 3 we exclude this variable from the model and show that our coefficient of interest remains stable. A mother’s indifference about children’s gender is not significantly connected with more children’s housework, but desiring more than four children is correlated with 0.40 more hours of children’s housework. The number of siblings is positively associated with hours of work in OLS estimates, but the number of sisters is insignificant in the random effect regressions. In robustness analysis we include instead either the number of younger brothers and older sisters of each child or the number of children aged 0–5 in the household. Research shows that the presence of an elder sister is associated with a lower level of housework and the reverse is true when a child has a younger brother or younger siblings (Emerson and Souza 2007). The literature suggests that the burden is particularly high for the eldest sister, who spends extra time looking after younger sibling or supplementing family income (Parish and Willis 1993). In robustness analyses not presented here, we find that having one older sister is associated with 0.54 fewer hours of housework, but having one younger brother with 0.55 more hours (both at p < 0.001). In column (3) of Table 3 the number of young children aged 0–5 in the household significantly correlates with increases in the amount of housework for children in our sample.

Consistent with Edmonds’ analysis (Edmonds 2007), it is unclear whether different types of labor activities are substitutes for each other. Working one additional hour for non-family members is associated with only 0.01 fewer hours of housework, but working one additional hour for family members on market production is associated with 0.17 more hours of household labor in the random-effects models. Finally, children in Muslim families, both boys and girls, perform less housework than their counterparts in non-Muslim families (most of which are Hindu). Conversely, children in North India, where severe son preference has been documented (Miller 1981; Arnold et al. 1998; Dyson and Moore 1983; Bhat and Zavier 2003) undertake more household tasks than those in other areas. Boys in the North undertake 0.87 more hours of housework than boys in other regions, and the parallel figure for girls is 1.57 (=0.87 + 0.7, p < 0.001). Finally, children in states with higher population density and infant mortality rates devote more hours to housework and those in relatively richer states do less.

Robustness

In the last columns of Table 3 we explore more in-depth some nuanced relationships between son preference, housework, and other children’s characteristics.

Age

To better understand the role of age, in column (4) of Table 3 we insert both an interaction between the child’s age and maternal son preference and a three-way interaction of those covariates with the gender of the child. As expected, the estimated coefficient for the three-way interaction is highly significant and implies widening of the gap between girls and boys living in families with a strong son preference, as compared to those with a girl preference, of 0.68 h of work per year of age. We obtain similar results in a specification with the binary SP index (not presented here), and produce the predictions of total hours of housework by son preference (ideal proportion of sons > 0.5 or ≤ 0.5) and children’s sex displayed in the right hand side of Fig. 1. The projected pattern fits nicely the observed data (the left panel), except for some underestimations among girls aged 12–14. Parental sex preference exerts little influence on boys’ provision of housework, but such a preference is clearly associated with higher levels of girls’ involvement in household labor, which increases in relative terms as girls age.

Caste

Another important dimension that has been shown to explain variation in son preference as well as sex ratios is caste (Arnold et al. 1998, Chakraborty and Kim 2010, Gaudin 2011). We define a high-caste variable that includes individuals who do not belong to a scheduled caste, scheduled tribe, or other backward class. Caste is missing in 9 % of the observations in the survey. The reference category of this variable includes both low-caste and no-caste families (such as Muslim or Christian). High-caste families in our sample do not have a significantly higher level of son preference than the rest. Not surprisingly in high-caste families children do less housework than in the other families and the gender gap is slightly smaller. Average hours of housework in high-caste families are 5.96 h for girls and 3.62 h for boys, a 2.3 h difference, whereas in the others, the average for girls is 7.51 h compared to 4.42 h for boys, a 3.1 h difference.

In column (5) of Table 3 we introduce in the model a control for whether children live in a high-caste household and three interactions of this variable: with son preference, Girl, and both son preference and Girl in a three-way interaction. Although positive, the coefficients for the two-way interactions of high caste with Girl and with son preference are not significant. Only the three-way interaction is highly significant and negative with a value of –2.64. The main coefficient for SP * Girl increases with respect to its original value in column (5) of Table 2 from 2.5 to 3.04, indicating that on average the gender gap is slightly larger in the separated sample of non-high-cast families. In net terms, however, son preference is still associated with a positive, though smaller, gender gap in high-caste families.

Religion

Previous literature has highlighted important religious differences in the intensity of the parental preference for male offspring. In general, results suggest that Hindus and, particularly, Sikhs (mostly concentrated in Northern India) have stronger son preference than Christians and Muslims (Bhat and Zavier 2003; Gaudin 2011). As a result, we hypothesize that the relevance of maternal son preference is likely to be less associated with actual differences in household behavior among the large minority of Indian Muslim than among other groups. In columns (6) and (7) of Table 3 we run the most complete specification separately for the sample of Muslims and non-Muslims. Findings confirm that in the sample of Non-Muslim children the estimated coefficient for the interaction of SP and the gender of the child is highly significant and larger than in previous estimates. Conversely, son preference is not associated with an increase in the gender gap of housework among Muslim children.

Family Size

Next we analyze whether the association between son preference and the gender gap in housework varies by number of children in the family. There are several reasons for conducting this analysis. First, the relationship between fertility outcomes and fertility preferences is dynamic. Preferences predict outcomes; but outcome themselves (i.e., the birth of a daughter or a son) impact the way many mothers rationalize them, particularly if they do not accord to their initially stated preferences. Unfortunately we lack longitudinal data to examine this dynamic process. However, by breaking down the sample by parity, we hope to obtain a snapshot of the extent/level of son preference at different levels of fertility.

Second, a separate analysis by family size reduces the complexity of controlling for sibling structure. The total number of children in the household and their sex composition by rank may influence how parents allocate household duties, as shown in Tables 2 and 3. In the full sample, however, it is difficult to control for the precise sibling structure since we observe 736 unique sex combinations of children across families. When we restrict the analysis to families of either two or three children the number of possible sex compositions across families drops to either 4 or 8, respectively.4

A caveat to conducting the analysis separately by family size is the sample selection bias introduced by not partitioning the sample randomly. Breaking down the current sample by family size is certainly not a random partition, as family size depends on factors such as parents’ age and fecundity. Furthermore, the number and sex composition of children is endogenous since families trying to have a boy may stop once they achieve it (Clark 2000; Arnold et al. 2002). In that regard a large family size may indicate a family’s search for sons and larger families are more likely to have more daughters. A recent paper by Rosenblum (2013) uses the sex of the first child as an instrument of family size to look at the implications of these stopping rules on the health and mortality of boys and girls. Moreover, a relatively smaller variation in son preference expected among larger families may bias the estimates of the impact of son preference on differential housework assignment downwards. Of course, the presence of sex selective abortion, another means to achieve a desired number of boys, reduces both the share of girls in the family and the overall household size (Das Gupta 1987;Das Gupta et al. 2003; Arnold et al. 1998, 2002; Bhat and Zavier 2003).

Basic cross-tabulations indicate that larger families are overrepresented in rural areas where the need for children’s input in the household is greater and the conventional gender division of work more prevalent. Only around 60 % of families with two children in our sample live in rural areas, whereas the same proportion is 73 % for those with four children. Similarly, the average ideal proportion of sons (SP index) increases with the number of children, from 0.53 in families with two children to 0.56 in families with four, whereas the share for whom the children’s gender does not matter moves down from 22 to 9 %.

Table 4 presents OLS estimates for one-child families, and a linear model with random effects for families with more than one child. For ease of comparison, column (1) includes the results for the entire sample presented earlier in column (1) of Table 3. The interaction between Girl and the binary index of son preference (SP > 0.5) is significant for all family sizes, though only at 5 % in the sample of single-child families. The magnitude of the coefficient decreases with family size. Single girls in families with son preference undertake around 1.6 h more of work than boys in similar families. The gender gap in families with son preference moves down from 1.1 h in those with two children, 0.73 h in those with three children, and to only 0.6 in those with four children. The decrease in size is possibly related to the fact that family size is endogenous to son preference, and to the larger availability of siblings to share the housework.

Table 4.

Weekly hours of housework in India by family size

| Variables | (1) All |

(2) 1 Child |

(3) 2 Children |

(4) 3 Children |

(5) 4 Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girl | −0.548*** (0.135) | 0.006 (0.472) | −0.158 (0.206) | −0.314 (0.268) | −0.747* (0.389) |

| Son preference (=1 if SP > 0.5) | −0.160** (0.081) | −0.442 (0.344) | −0.135 (0.161) | −0.160 (0.145) | −0.071 (0.196) |

| SP (=1 if SP >0.5) * Girl | 0.862*** (0.099) | 1.594** (0.628) | 1.109*** (0.244) | 0.735*** (0.175) | 0.603*** (0.222) |

| Constant | 2.550*** (0.282) | 1.075 (0.786) | 0.527 (0.402) | 0.503 (0.504) | 0.509 (0.681) |

| Observations | 80,657 | 2,752 | 18,483 | 22,003 | 16,151 |

| R2 | 0.142 | ||||

| Number of groups | 3,847 | 3,400 | 3,471 | 2,771 |

OLS in the sample of families with one child and linear model with random effects for all other columns. Models include all mother and children’s characteristics, state characteristic, and regional and religious controls as in column (5) of Table 2

Standard errors in parentheses

p <0.05;

p <0.01;

p <0.001

Source NFHS-3, 2005

Results from the sibling structure suggest that older children (in terms or their rank in their family) undertake more household tasks than younger ones. Consistent with the estimate from the full sample, the presence of a sister is in general associated with fewer hours of housework in families of three and four children. The older sister disadvantage is particularly strong in families of four children that are more likely to reside in rural areas. Detailed results are available online.

Media Exposure

As noted in the conceptual section, gender role attitudes may mediate the relationship between the preference for sons and gender differentials in children’s housework. Egalitarian gender roles are often emphasized in mass media, and watching TV exposes people to new ways of thinking, and leads to attitudinal change (Bhat and Zavier 2003; Barber and Axinn 2004; Chung and Das Gupta 2007). Jensen and Oster (2009) find that the introduction of cable TV in selected rural areas closes large part of the difference in son preference in those villages as compared with urban areas. Since the NFHS-3 does not explicitly inquire parents about gender role orientation; we use mother’s exposure to media (TV, radio, and newspaper) as a proxy.5 Over 20 % of the families report having no access to any of the three types of modern media. Mothers’ low media exposure is closely associated with a larger gender gap in housework as well as with girls spending more hours on housework. When we introduce this covariate in the models, both alone and interacted with Girl, the coefficient for SP * Girl decreases somewhat in size (around 15–20 %), but remains highly significant. We recognize that media exposure is likely an endogenous variable correlated with son preference-which likely accounts for this finding. Because of its exogenous nature, Jensen and Oster (2009) are able to use the timing of the introduction of cable TV in a panel of Indian villages as an instrument for the increased autonomy of women. Unfortunately, the available regional detail and sample size in NFHS-3 precludes us from using a similar type of instrument and we choose to omit this covariate from the main tables in the paper. However, results are available upon request.

A Two-Part Model of Children’s Work

As mentioned in the descriptive analysis, 40 % of the eligible children did not contribute any housework during the survey week and only 7.2 and 7.4 % worked for non-household members and household members, respectively, on alternative activities such as farm labor, family business, or street vending. Although the validity of the findings of the paper does not depend on the level of children’s participation in these activities, the high frequency of zero hours of work in the sample cannot be ignored. To better investigate the relevance of son preference on both the extensive as well as the intensive margin of child labor and whether it is correlated in a distinct way across different types of labor, we estimate a set of models of participation (whether the child does any work at all or not), hours of work for the whole sample, and hours of work among those who exert positive effort in one activity. Each column in Table 5 presents the coefficient for the interaction of SP and Girl for the three types of labor and for different estimation methods. In the first row, the gender gap in children’s participation in some form of work among families with son preference is significant only in the logistic models of housework. The second row of Table 5 shows that in the sample of all children, the gender gap in hours of housework is positive, but the gap for market-related work (both with household and non-household members) is negative and marginally significant at 10 %. This is consistent with the hypothesis presented in the conceptual framework that families with strong son preference choose to devote boys’ time to more productive activities (preferably to build their human capital). When the sample is limited to children with positive hours in an activity, the gender gap is positive and significant in all models of housework and negative (but not significant) for other types of work.

Table 5.

Son preference and children’s participation and weekly hours in different types of work

| Estimated coefficient SP (=1 if SP > 0.5) * Girl | Housework | Work for household members | Work for non-household members |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||

| Participation (Logit) | 0.234*** (0.037) | 0.016 (0.071) | −0.003 (0.004) |

| Hours—all children (random effects) | 0.862*** (0.099) | −0.112* (0.062) | −0.141* (0.081) |

| Hours—children with positive hours | N = 45,397 | N = 4,558 | N = 5,372 |

| Hours (OLS) | 0.672*** (0.165) | −0.543 (0.769) | −1.529* (0.911) |

| Hours (random effects) | 0.667*** (0.136) | −0.242 (0.626) | −0.728 (0.624) |

| ln hours (random effects) | 0.031** (0.013) | −0.028 (0.046) | −0.058 (0.048) |

Each coefficient for SP (=1 if SP > 0.5) * Girl corresponds to a separate model (Logit, OLS, or random effects) that also includes all mother and children’s characteristics, state characteristic, and regional and religious controls as in column (5) of Table 2

The sample size for the models in the first two rows is N = 80,678. Standard errors in parentheses

p <0.1;

p <0.05;

p <0.01

Source NFHS-3, 2005

To better illustrate how participation matters, we employ a two-part model (Pohlmeier and Ulrich 1995) to produce the predictions for an average boy or girl at different levels of son preference in Table 6.6 First, we estimate whether a child provides household labor or not using a random-effects logistic model. Then, among those who help with household chores, we estimate how many hours they spend on chores, using a log-normal model with random effects. We assume the random effects in the first stage are independent of those in the second stage.7 The estimated interaction between son preference and girl is positive and significant at the 1 % level in both stages (see the supplementary material Appendix). Predictions in the first row of Table 6 show how son preference (SP > 0.5) is associated with a large gender difference in the probability of providing household labor during the survey week. When the ideal proportion of sons is ≤0.5, there is a 17-point gender difference in the probability of performing housework. When the ideal proportion is >0.5, it significantly doubles to 36 points. In the second stage, son preference is correlated with a wider gender gap in hours of household labor during the survey week. When there is no son preference, the gender difference in housework totals 1.99 h. When the ideal proportion of sons is <0.5, the difference increases significantly to 2.38. By combining predictions from stage 1 and 2 we obtain the expected hours of housework among all children. When there is no son preference, the gender difference amounts to 2.99 h, but it significantly increases to 4.34 h when there is preference for boys.

Table 6.

Participation in housework and weekly hours of housework: predictions from a two-part model, by sex and level of son preference

| No son preference (ideal proportion ≤ 0.5) | Son preference (ideal proportion > 0.5) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Boy | Girl | Girl–Boy | Boy | Girl | Girl–Boy | |

| Stage 1: probability of performing housework | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.49 | 0.85 | 0.36 |

| Stage 2: hours of housework, among those with positive hours | 7.54 | 9.53 | 1.99 | 7.62 | 10.00 | 2.38 |

| Stage 1 and 2 combined: predicted hours of housework | 4.46 | 7.45 | 2.99 | 4.41 | 8.76 | 4.34 |

Source Predictions based on a two-stage model: (1) random-effects logistic model of participation in housework among all children (N = 80,678, Groups = 3,847) (xtmelogit in Stata); (2) random-effects log-normal model of hours of work among those with positive hours (N = 45,397, Groups = 3,722) (xtmixed in Stata). The coefficients for the interaction SP * Girl in each stage are 0.319 and 0.031 both significant at 1 % level. Complete estimates are available in the supplementary material Appendix. The models include all mother and children’s characteristics, state characteristic, and regional and religious controls as in column (5) of Table 2

Source NHSF-3, 2005

Measuring Son Preference with Fertility Intention

As explained before, using the ideal proportion of sons as a measure for son preference has two potential problems. First, women may provide socially desirable answers rather than report their actual preference. Second, as Bankole and Westoff (1998) first noted, this measure may suffer from a problem of time-consistency at the individual level, although at the aggregate level it is consistent with fertility outcomes.

To address this issue, we employ another measure to gauge son preference, namely fertility intention as suggested by Bankole and Westoff (1998). An intention to have another child, especially when there is an equal number of boys and girls, is likely to be driven by a desire for sons over daughters. Few Indian parents want more daughters than sons, and our preliminary analysis has confirmed the association between fertility intention and the foregoing son preference index.

We limit the analysis of fertility intention to families with exactly one son and one daughter, for two reasons. First, we want the initial number of boys and girls to be equal in the family (otherwise the intention may suggest preference for balanced sex composition). Second, since most Indian women nowadays desire 2 or 3 children, few women who are already mothers of four or more children remain interested in bearing another child. The sample size (10,059) is much smaller than the original one (80,647) and there are only 435 children in this subsample whose families intend to have another child. We estimate the following linear equation using both OLS and random-effects regression,

where the main variable of interest in this analysis is the interaction between the mother’s intention to have more children and the child’s gender (Girl). Results in Table 7 are consistent with our hypothesis. The first two columns present estimates for the full sample and columns (3) and (4) restrict the sample to non-Muslim children. Fertility intention, a surrogate for son preference, is associated with close to 1 h increase in the additional time a girl spends on housework relative to a boy when the mother desires more children, though the coefficient is only marginally significant in the random-effects estimates in column (2). When the sample is limited to non-Muslim children we find that the intention to have an additional child is significantly associated with an increase of the gender gap in workload of 1.5 h in both columns (3) and (4).

Table 7.

Mother’s fertility intention and children’s weekly hours of housework in India

| Variables | (1) All |

(2) All |

(3) Non-Muslim |

(4) Non-Muslim |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girl | −0.120 (0.173) | −0.154 (0.254) | −0.080 (0.179) | −0.116 (0.264) |

| More children | 0.084 (0.528) | −0.107 (0.431) | 0.181 (0.635) | −0.082 (0.479) |

| More children * Girl | 0.971 (0.685) | 0.991* (0.515) | 1.547* (0.857) | 1.565*** (0.585) |

| Constant | 1.143** (0.511) | 1.298** (0.535) | 1.041* (0.545) | 1.164** (0.558) |

| ln(SD(PSU)) | 0.755*** (0.051) | 0.759*** (0.052) | ||

| ln(SD(family level)) | 1.106*** (0.032) | 1.094*** (0.033) | ||

| ln(SD(residual)) | 1.470*** (0.012) | 1.461*** (0.013) | ||

| Observations | 10,059 | 10,059 | 9,254 | 9,254 |

| R2 | 0.170 | 0.176 | ||

| Number of groups | 2,828 | 2,639 |

Sample of families with exactly one boy and one girl. OLS in columns (1) and (3) and random-effects model in columns (2) and (4). The models include all mother and children’s characteristics, state characteristic, and regional and religious controls as in column (5) of Table 2

Robust standard errors in parentheses

p <0.01;

p <0.05;

p <0.1

Overall, the predicted hours of housework for boys and girls, both in families that intend to have more offspring and in those who do not, from the model in column (2) is lower than those in Fig. 2, which are based in the entire sample. The average boy does a fairly similar number of hours regardless of whether his mother intends to have a third child (2.76 if she does not and 2.63 if she does), whereas the average girl does about 1 h more if the mother wants more children (5.1 h up from 4.1 h if the mother does not). A likely explanation for this is that the demand for housework is positively associated with family size and that large families tend to live in rural areas. Since the analysis of fertility intention is restricted to two-child families here, the total burden of housework is smaller in this subsample than in the full sample.8

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper is the first study to analyze whether son preference correlates with larger gender gaps in the hours of housework children undertake in Indian families. Close to 50 % of children in our sample are involved in housework, a number much larger than for other types of work (around 7–8 %). Understanding the role that social norms and parental attitudes play in children’s time use is a matter of interest both for academics and policy makers. A large literature has studied the determinants of son preference such as absolute and relative, wealth, religion, or kinship (Dyson and Moore 1983; Arnold et al. 1998; Bhat and Zavier 2003; Chakraborty and Kim 2010; Gaudin 2011). Son preference is pervasive in India, a country with a large proportion of missing women (Sen 1992) and abnormal sex ratios (Das Gupta 1987; Agnihotri 2000; Agnihotri et al. 2002; Murthi et al. 1995; Jha et al 2006). We construct an index of son preference based on a mother’s ideal proportion of sons that allows for a larger dispersion of son preference than Bhat and Zavier’s (2003) and discriminates over different family structures and preferences on the number of girls in a similar way as Gaudin’s (2011). With it we estimate both OLS and random-effects models of hours of housework for all children and find that son preference is correlated with an increase in girls’ relative burden of housework of around 2.5 h (and of around 0.7 h when a dichotomous measure of SP is employed). This association is significant across different family sizes, weaker but still significant for high caste and not significant among Muslims. Girls in families with son preference are relatively more likely to exert positive hours of housework, but not of other types of work.

The SP index has several limitations. Without longitudinal data and given the retrospective nature of the questions, we cannot ascertain whether the gender preferences a woman reports in the survey are affected by her current satisfaction with her own children. Second, subjects’ intentional misreporting may bias our estimates of the relationship between son preference and the gap in the time spent on housework between boys and girls by introducing some measurement error in our son preference variable that we cannot assess with our data. If more educated women, who live mostly in urban areas, were more likely to hide their genuine son preference than less educated women, the observed variation in (self-reported) son preference would be primarily driven by subjects in rural areas. The robustness of the result to both running the models separately for urban and rural areas as well as for different educational attainments and the use of the alternative measure of son preference based on fertility intentions (“Measuring Son Preference with Fertility Intention”) indicates that if it exists, the bias is not driving fundamentally our findings.

In this study, we compare the gender gap in housework among children in families with son preference and the rest. Future extensions should focus more in-depth on within-household time allocation of different activities such as study, leisure, formal employment, or participation in family business (Beblo 2001). For a complete understanding of within-household decisions, the contribution of the mother to household tasks should be accounted for, since adult females in the family may take a larger burden, especially in the absence of girls, if they perceive that boys’ time should be allocated either to more productive activities to gain human capital or to leisure. Unfortunately this information is not available. Similarly, we are unable to control for either children’s leisure time or their time for education that may be affected when the family’s demand for labor rise (Edmonds 2007). Most studies consider schooling as the only relevant opportunity cost of work (Emerson and Souza 2007), even when in most cases children undertake both tasks simultaneously, but forget about leisure and its relevance for children. Thus a larger burden of housework for girls may decrease their playtime and their ability to be just children. In the future, the use of time diaries may provide a fuller picture of which children’s activities suffer when they engage in more housework. Finally, we lack data on what kind of additional chores parents assign to girls when there is male preference, whether traditional feminine tasks, such as cooking and caretaking of family members, or rather some more masculine tasks, such as fixing furniture, that would more strongly suggest that considerations other than gender socialization are at work (Blair 1992).