Abstract

Background

In Canada, many diverse models of integrative oncology care have emerged in response to the growing number of cancer patients who combine complementary therapies with their conventional medical treatments. The increasing interest in integrative oncology emphasizes the need to engage stakeholders and to work toward consensus on research priorities and a collaborative research agenda. The Integrative Canadian Oncology Research Initiative initiated a consensus-building process to meet that need and to develop an action plan that will implement a Canadian research agenda.

Methods

A two-day consensus workshop was held after completion of a Delphi survey and stakeholder interviews.

Results

Five interrelated priority research areas were identified as the foundation for a Canadian research agenda:

Effectiveness

Safety

Resource and health services utilization

Knowledge translation

Developing integrative oncology models

Research is needed within each priority area from a range of different perspectives (for example, patient, practitioner, health system) and in a way that reflects a continuum of integration from the addition of a single complementary intervention within conventional cancer care to systemic change. Strategies to implement a Canadian integrative oncology research agenda were identified, and working groups are actively developing projects in line with those strategic areas. Of note is the intention to develop a national network for integrative oncology research and knowledge translation.

Conclusions

The identified research priorities reflect the needs and perspectives of a spectrum of integrative oncology stakeholders. Ongoing stakeholder consultation, including engagement from new stakeholders, is needed to ensure appropriate uptake and implementation of a Canadian research agenda.

Keywords: Integrative oncology, research priorities, consensus development, Canada, complementary medicine, cam

1. INTRODUCTION

With more than half of all cancer patients using complementary therapies1–5, numerous innovative models for integrative oncology care have emerged across Canada and internationally. Integrative oncology is typically defined as an evidence-based whole-person approach to cancer care that responds to the increasing tendency among cancer patients to combine complementary approaches such as naturopathic medicine, acupuncture, and meditation with conventional medical care to manage their cancer experiences6,7. In practice, however, the structure and form of integrative oncology models vary widely. In Canada, there are examples of programs that are community-based and others that are hospital-based; some are led by medical doctors, and others, by naturopathic doctors or nurses; some are privately funded, and others receive public funds. Each program seems to offer a different combination of therapies and to place a different level of emphasis on patient care, research, and education. A recent systematic review of published examples of integrative oncology programs internationally demonstrated wide variation in administrative, operating, and funding structures and concluded that there is no “gold standard” model8.

The current structure of integrative oncology in Canada provides great opportunity for innovation, but the increasing interest in, and development of, diverse integrative oncology models emphasizes the need to coordinate efforts and to study established models to learn what is working well and what is not. There is a need to engage a broad range of relevant stakeholders and to work toward consensus with respect to research priorities and a collaborative research agenda to best guide Canadian practice and policy moving forward.

In 2008, a consensus-building workshop was held to develop a vision, principles, and research priorities for integrative oncology in Canada. The workshop was organized by the Cancer and Complementary and Alternative Medicine Research Team, which was established in 2001 by the Sociobehavioural Cancer Research Network with funds from the Canadian Cancer Society. As a result of the workshop, interdisciplinary partnerships were formed that are intended to motivate Canadian practice and policy change to reflect the integrative oncology approach.

Workshop participants articulated a draft vision and guiding principles for integrative oncology in Canada and identified several barriers to implementing the vision. The guiding principles focused on a series of needs:

To be inclusive of multiple disciplines and perspectives

To ensure effective communication between patients and health care providers

To ensure that evidence includes science-based knowledge and practitioner-based wisdom

To acknowledge patients as experts concerning their own health and experiences living with cancer

Several recommendations related to the development of a conceptual framework and research agenda for integrative oncology also emerged, and most have been implemented since the 2008 meeting. For example, a national working group—the Integrative Canadian Oncology (icon) Research Initiative—was formed out of the Cancer and Complementary and Alternative Medicine team. The new group has a mission to facilitate the creation, synthesis, and translation of evidence-informed integrative oncology to motivate practice and policy change within Canada. A primary activity for the icon Research Initiative has been to further develop Canadian integrative oncology research priorities and a research agenda, as recommended at the 2008 meeting. Assisted by a Meetings, Planning and Dissemination grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, a consensus-building process inclusive of a broad range of stakeholders was initiated.

Specific objectives of the consensus-building process were these:

To identify specific research questions that form a coherent research program related to models of integrative oncology

To strengthen existing relationships and develop new ones so as to ensure a coordinated and collaborative approach to the study of integrative oncology models and to facilitate uptake of research results

To develop practical research initiatives to motivate further practice and policy change

To prioritize an action plan and a timeline

The purpose of the present paper is to describe the methods used within the consensus-building process and to report on progress made in relation to the stated objectives. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research had no role in data collection, analysis, or interpretation and did not have the right to approve or disapprove publication of this manuscript.

2. METHODS

Members of the icon Research Initiative and the Ottawa Integrative Cancer Centre organized a two-day consensus workshop to achieve the stated objectives. The workshop was preceded by a Delphi survey and stakeholder interviews, as described next.

2.1. Pre-Workshop Delphi Survey

A 3-round Delphi survey9,10 was conducted before the workshop with a wide range of stakeholders to obtain input and to work toward consensus on integrative oncology research priorities. The Delphi technique involves seeking the opinion or judgment of a panel of individuals knowledgeable about the subject under consideration by presenting a series of structured questionnaires to the panelists. The responses from each round of questionnaires are then returned to all participants in a summarized form, with a request to communicate further judgments anonymously back to the group. The process continues until consensus is reached, typically in 3 or 4 rounds.

Conducting a Delphi survey in advance of the workshop ensured the engagement of a broad range of participants beyond those able to physically attend and also facilitated a productive discussion during the workshop. Delphi participants were recruited from attendees at the 8th Annual Conference of the Society for Integrative Oncology, an e-mail list maintained by the Canadian Interdisciplinary Network for Complementary and Alternative Medicine Research, and the personal contacts of the workshop organizers. To be eligible, participants had to self-identify as actively engaged in the integrative oncology field. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board.

In round 1, participants selected up to 3 priority research areas from a pre-identified list and provided suggestions for priority topics within each area. Allowance was made for the addition of topics that participants might feel were missing from the pre-identified list. In round 2, participants revisited their selections for priority research areas based on round 1 results and then selected up to 3 priority research topics within each area. In the final round, participants ranked the priority research areas and topics in their perceived order of importance to Canadian integrative oncology practice and policy. Between the Delphi rounds, responses were collated and summarized before being presented to participants for the subsequent round. Most Delphi communication was electronic, facilitated through a Canadian Web-based survey tool: FluidSurveys (http://www.fluidsurveys.com).

2.2. Pre-Workshop Stakeholder Interviews

Before the workshop, telephone interviews were conducted with 6 workshop participants to explore emergent ideas about integrative oncology and related research in Canada, and to identify any possibly divergent perspectives among participants and stakeholder groups. Interviewees were selected to ensure representation from all stakeholder groups and a variety of professional backgrounds. Interviews were semi-structured, lasted between 20 and 30 minutes, and were conducted by the facilitator as part of workshop preparation. During the interviews, participants were asked to reflect on the priority research areas and topics that emerged from the Delphi survey and to give an opinion about the ranking of the areas and topics, including whether they felt that any areas or topics were missing. Participants were further asked how they envisioned integrative oncology in Canada, the barriers to making integrative oncology happen, and the most important research questions that need answering.

2.3. Two-Day Stakeholder Consensus Workshop

The two-day workshop—held April 24–25, 2012, in Ottawa, Ontario—attracted 19 participants (Table i). The workshop objectives were these:

Reaffirm the essential elements of integrative oncology, including a vision and guiding principles.

Reach consensus on Canadian integrative oncology research priorities and a research agenda.

Develop strategies and an action plan to implement a Canadian integrative oncology research agenda.

TABLE I.

Workshop participants, in alphabetic order

| Participant | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Lynda Balneaves rn phd | UBC School of Nursing, Vancouver, BC |

| Bob Bernhardt med llm phd | Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine, Toronto, ON |

| Maya Bobrowska bsc | Patient advocate, Ottawa, ON |

| Heather Boon bscphm phd | University of Toronto, Toronto, ON |

| Ruth Carriere mpa | Patient advocate, craniosacral and energy practitioner (Retired) director, Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON |

| Catherine Caule ab mba | Patient advocate, Ottawa, ON |

| Gary Deng md | Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center, NY, U.S.A. |

| Paula Doering rn | Cancer Care Ontario regional vice president, Champlain Regional Cancer Program |

| Dean Fergusson mha phd | Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, ON |

| Hal Gunn md | InspireHealth, Vancouver, BC |

| Fatima Haggar mph | The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON |

| Anne Leis phd | University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK |

| Doreen Oneschuk md ccfp | Grey Nuns Hospital, Edmonton, AB |

| Stephen Sagar mb mrcp frcr frcpc | Juravinski Cancer Centre, Hamilton, ON |

| Dugald Seely msc nd fabno | Ottawa Integrative Cancer Centre, Ottawa, ON |

| Burleigh Trevor Deutsch phd llb mphil | Consultant in ethics, Ottawa, ON |

| Marja Verhoef phd | University of Calgary, Calgary, AB |

| Shailendra Verma md frcpc facp | Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre, Ottawa, ON |

| Laura Weeks phd | Ottawa Integrative Cancer Centre, Ottawa, ON |

| Bonita Ford ma | Workshop Facilitator |

One week before the workshop, participants were given a set of background readings to facilitate their equal understanding of current directions in integrative oncology and related research in Canada. Readings included a book chapter describing the evolution of integrative oncology from its beginnings within “complementary and alternative” health care11, a report describing the process and results of the 2008 consensus-building workshop, and a summary of the Delphi survey methods and results.

During the workshop, a variety of formats were used to facilitate egalitarian and productive dialogue, including small group work, facilitated group discussions, and a brainstorming exercise using a paired “speed-dating” format. Two brief didactic presentations were offered to set the stage and provide background for the workshop, and to describe the Delphi survey and results.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Pre-Workshop Delphi Survey

The Delphi survey attracted 81 participants for round 1, 52 for round 2 (64.2% response from prior round), and 48 for round 3 (92.3% response from prior round). Throughout the 3 rounds, consensus was achieved concerning 5 priority research areas thought to best advance integrative oncology practice and policies in Canada:

Clinical effectiveness

Development of practice models

Education and training

Cost effectiveness

Safety

There was clear consensus throughout all the Delphi rounds that clinical effectiveness is a top research priority, but consensus was not obtained about the relative importance of the remaining 4 priority areas. After clinical effectiveness research, participants who identified themselves as researchers, oncologists, and other health care practitioners tended to place greater importance on studying the development of practice models; educators tended to place greater importance on studying education and training.

Tables ii and iii summarize the Delphi results, which include the results of the round 3 (final) ranking process. The boldface type in each table helps to indicate the ranking or relative priority given to each research area. In cases in which consensus was not achieved for an overall rank within a research agenda, more than one table entry uses boldface type. For example, after the three Delphi rounds, it was not clear whether education and training should be the third or fourth priority within a research agenda, and so the text in the entries for both rank 3 and rank 4 appears in boldface in Table ii.

TABLE II.

Round 3 results of a Delphi survey to rank Canadian integrative oncology research priorities

| Research areaa |

Round 3 priority rankings [n (%)]

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Clinical effectivenessb | 43 (90) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Developing practice modelsc | 3 (6) | 22 (46) | 7 (15) | 5 (10) | 11 (23) |

| Education and trainingd | 0 (0) | 10 (21) | 16 (33) | 17 (35) | 5 (10) |

| Cost effectivenesse | 0 (0) | 10 (21) | 13 (27) | 13 (27) | 12 (25) |

| Safetyf | 2 (4) | 4 (8) | 11 (23) | 12 (25) | 19 (40) |

Four of the five priority research areas emerging from this Delphi process were renamed after discussions at the 2-day consensus workshop as further described in Table vi.

Includes defining the aspects of care that enhance effectiveness, the mechanisms involved, and the methods for investigating effectiveness, and identifying appropriate outcomes from the perspective of key stakeholders.

Includes defining key steps to establishing and evaluating care, stakeholder involvement, and facilitators and barriers to the practice and uptake of integrative oncology.

Includes strategies to educate practitioners, patients, their caregivers, and the community to ensure safe and effective integrative oncology.

Includes financial and other resource allocations and their relationships to patient outcomes, emphasizing in part the comparative cost-effectiveness of integrative and conventional cancer care.

Includes defining the aspects of integrative oncology that enhance patient safety, the mechanisms by which safety is improved, and methods for assessing patient safety in integrative care models. Direct events (for example, adverse events) and indirect events (for example, diverting a patient from other therapies that may be beneficial) are both considered.

TABLE III.

Top three ranked research topics within each of 5 Canadian integrative oncology research priorities emerging from a 3-round Delphi surveya

| Research area | Research topics | Round 3 rankings [n (%)]b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Clinical effectiveness | 1. Impact of integrative oncology on symptom management and quality of life (for example, dyspnea, nausea, fatigue) | 37 (77) | 5 (10) | 0 |

| 2. Impact of integrative oncology on cancer progression (for example, mortality, recurrence, metastasis) | 5 (10) | 26 (54) | 11 (23) | |

| 3. Identifying appropriate clinical and patient-reported outcomes to assess clinical effectiveness of integrative oncology | 2 (4) | 6 (13) | 21 (44) | |

| Developing practice models | 1. Interdisciplinary collaboration, including identification of team members and their relationships, and strategies to promote effective collaboration | 31 (65) | 9 (19) | 3 (6) |

| 2. Essential steps to establishing and evaluating an integrative oncology program | 8 (17) | 15 (31) | 12 (25) | |

| 3. Strategies to facilitate acceptance and uptake of integrative oncology | 4 (8) | 15 (31) | 13 (27) | |

| Education and training | 1. Developing and evaluating evidence-informed standards and guidelines for integrative oncology practice | 37 (77) | 7 (15) | 2 (4) |

| 2. Developing and evaluating knowledge translation strategies to enable evidence-informed integrative oncology practice | 4 (8) | 24 (50) | 7 (15) | |

| 3. Developing and evaluating practitioner-focused education resources relevant to integrative oncology | 3 (6) | 9 (19) | 20 (42) | |

| Cost effectiveness | 1. Impact of integrative oncology on conventional health care utilization | 26 (54) | 17 (35) | 2 (4) |

| 2. Short- and long-term cost effectiveness of integrative oncology | 14 (29) | 22 (46) | 3 (6) | |

| 3. Describing direct and indirect financial and other resources required to provide integrative oncology | 3 (6) | 7 (15) | 30 (63) | |

| Safety | 1. Understanding and describing interactions and contraindications | 40 (83) | 4 (8) | 0 |

| 2. Better defining components of integrative oncology that contribute to (and are essential for) patient safety | 2 (4) | 28 (58) | 11 (23) | |

| 3. Identifying situations in which harm might result from avoidance of conventional therapy | 2 (4) | 8 (17) | 21 (44) | |

Four of the five priority research areas emerging from this Delphi process were renamed after discussions at the 2-day consensus work-shop as further described in Table vi.

Only the three highest-ranked research topics within each priority area are presented, together with the number and percentage of participants assigning those topics a ranking of 1, 2, or 3.

3.2. Pre-Workshop Stakeholder Interviews

Interview participants agreed that the five priority research areas from the Delphi survey were a strong foundation for a Canadian research agenda, but opinions about the rankings varied: Some interviewees agreed with the rankings, some offered different rankings, and one participant found ranking difficult and thought that all areas “go hand-in-hand.” Opinions about how a research agenda could, or should, prioritize specific topics within each priority area similarly varied. It was clear there would be nearly as many opinions about how to move forward as participants in the two-day workshop. With respect to the workshop, many interview participants emphasized that all integrative oncology stakeholders needed to be equally represented, including patient advocates.

3.3. Two-Day Stakeholder Consensus Workshop

The 19 workshop participants represented a broad stakeholder group, inclusive of cancer researchers, biomedical and complementary medicine practitioners, patient advocates, knowledge users, and an ethicist. The agenda was organized around the three workshop objectives. Workshop results are summarized next, according to each pre-defined workshop objective.

3.3.1. Objective 1

To meet the objective “Reaffirm the essential elements of integrative oncology, including a vision and guiding principles,” participants reflected on the vision and guiding principles that resulted from the 2008 consensus-building workshop (Table iv). There was agreement that the previously articulated vision included many of the essential elements of integrative oncology, including a focus on the patient and practitioner as equal partners in a healing journey, guided by empowerment, patient choice, and evidence. Participants also agreed that the previously articulated vision was too long and instead should focus on the elements that distinguish integrative oncology from standard oncology practice. Common themes and elements that potentially distinguish integrative oncology from standard practice, raised in both small- and full-group discussions, were patient- and whole-person–centered practice; collaboration and teamwork; empowerment; and evidence, wisdom, and trust (Table v). Further, a need to clarify an overall goal for integrative oncology was recognized. For example, it is unclear whether the goal is to work toward a new model of cancer care, to have integrative oncology emerge as a specialty form of care offered to those who want it or who might benefit most, or something else entirely. Overall, there was agreement that continued discussion is warranted and should be inclusive of a larger and more representative group of Canadian integrative oncology stakeholders. Further, the discussion should be particularly informed by the proposed distinguishing elements of integrative oncology.

TABLE IV.

2008 Draft vision and guiding principles for integrative oncology in Canada

| The consensus-building workshop described in the present report builds on a 2008 consensus workshop also organized by the icon Research Initiative, then known as the Cancer and Complementary and Alternative Medicine Research Team. During the 2008 workshop, stakeholders gathered and articulated a vision and guiding principles for integrative oncology in Canada, as outlined here. |

|

|

| A Canadian vision for integrative oncology |

| In Canada, integrative oncology is an approach to delivering cancer care and services that privileges the patient’s voice, places the patient and family at the centre of the decision-making process, and acknowledges the patient as a whole person—mind, body, and spirit. |

| It is based on a specialized body of knowledge generated through a well-funded research agenda and focused on evaluation of cancer care in real-world settings. The evaluation includes cost-effectiveness and quality-of-life outcomes in addition to safety and efficacy. |

| Aligned with Canadian national health care principles and reimbursement strategies, integrative oncology is accessible and affordable for any patient living with cancer, and is based on a set of widely accepted, clearly communicated standards of practice. It supports patients to integrate a therapy or practice from any health belief system that is assessed to be safe and effective for that individual. |

| Health care professionals who practice integrative oncology have a greater satisfaction in their work than many health professionals because they feel supported to provide health care that more closely matches the needs and desires of their patients. They see themselves as patient and family guides who understand that cancer can be a personally transformative experience and that delivering biomedical cancer treatment within a true healing environment enhances outcomes, including hope. |

| Guiding principles |

|

TABLE V.

Proposed elements that distinguish integrative oncology from standard oncology practice

| Distinguishing element | Description |

|---|---|

| Patient- and whole-person centred | Integrative oncology care ensures that the unique and individualized needs of each patient are met at every step during their experience with cancer, within one seamless health care system that includes both complementary and conventional therapies. |

| Collaboration and teamwork | Effective collaboration and teamwork across a diverse range of professions and disciplines, including both conventional and complementary disciplines, is essential to provide continuous and seamless integrative patient care. |

| Empowerment | In an integrative model, the role of the health care practitioner is to empower patients to become active participants in their healing. The role of administrators is to empower health care practitioners to fulfill that role, while offering integrative care that includes a range of therapies regardless of philosophic origin. |

| Evidence, wisdom, and trust | Although research evidence must guide integrative practice and policies, the traditional notion of “evidence” should be expanded to reflect practitioner wisdom and a trust in the patient to make informed choices. |

3.3.2. Objective 2

In meeting the objective “Reach consensus on Canadian integrative oncology research priorities and a research agenda,” participants agreed that the 5 priority research areas that emerged from the Delphi survey should form the basis of a Canadian integrative oncology research agenda and should guide individual studies within the agenda. Diverse studies within each research area are clearly needed, and participants agreed that, when planning any particular study, it would be beneficial, where feasible, to include experts from each area and to assess outcomes across the entire spectrum.

Each stakeholder group initially placed different emphases on the importance of each priority area, but in a facilitated group discussion, consensus was reached that the 5 identified areas are interrelated and that a ranking should not be imposed. Throughout the discussion, participants offered several points of clarification to refine the priority research areas within the framework, including renaming 4 of the 5 areas to better reflect priority research in the field (see Table vi). An important discussion point was that the priority areas are not unique to integrative oncology and instead relate to oncology more broadly; however, participants were clear that the development of a Canadian research agenda should be guided by the distinguishing elements of integrative oncology as described earlier.

TABLE VI.

Participant suggestions to refine Canadian integrative oncology research priorities within a research framework

|

Priority research area

|

Reason for name change | |

|---|---|---|

| Before consensus workshop | After consensus workshop | |

| Education and training | Knowledge translation | To reflect the need to synthesize, disseminate, and exchange knowledge between researchers and knowledge users, and not only to educate and train professionals. |

| Clinical effectiveness | Effectiveness | To reflect a need to focus on outcomes within integrative oncology beyond clinical outcomes—for example, within the community and broader health care system. |

| Cost effectiveness | Resource and health services utilization | To ensure that the effects on resources other than health care dollars are assessed as part of studying integrative oncology models. |

| Developing practice models | Developing integrative oncology models | To reflect a focus on research and education, in addition to practice, within integrative oncology. |

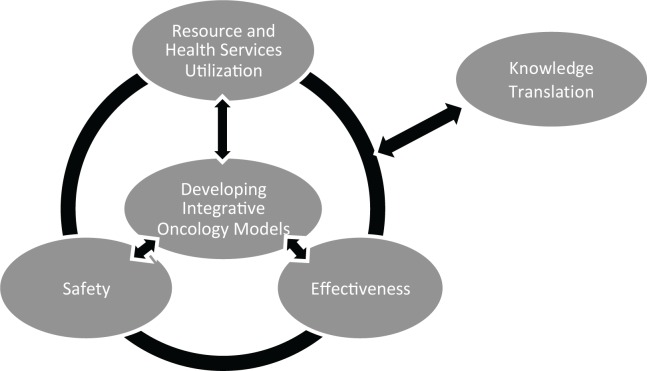

Participants also suggested drafting a framework diagram to illustrate the interrelatedness of the research areas and, in particular, the iterative relationship between research and knowledge translation. Figure 1 presents a preliminary diagram. Within the preliminary diagram, “Developing Integrative Oncology Models” is placed in the middle to indicate that established models should be the focus of a research agenda, because they represent the sites where studies in all other areas will take place and where results will be implemented. “Knowledge Translation” is placed on its own to indicate its separation from knowledge creation related to “Safety,” “Effectiveness,” and “Resource and Health Services Utilization” within integrative oncology models, but also to indicate the iterative relationship between knowledge creation and translation in those areas.

FIGURE 1.

Draft diagram of Canadian integrative oncology research priorities.

3.3.3. Objective 3

In meeting the objective “Develop strategies and an action plan to implement a Canadian integrative oncology research agenda,” participants took an opportunistic approach to develop an action plan for implementing the emerging research agenda. Rather than articulate a set of specific studies that reflect the priority research areas, participants agreed that it would be more productive to take advantage of the expertise in the room and to capitalize on existing research programs and opportunities. In essence, participants chose to identify the “low-hanging fruit” so as to make short-term progress while planning a longer-term sustainable research program.

In an exercise that used a paired “speed-dating” format, each participant was given a few minutes to talk with every other participant and to explore the potential for collaboration between existing projects and organizations. Participants were asked to record their top three strategies on sticky notes, which were then applied to the wall under the relevant priority research areas. Each participant then individually voted (with coloured stickers) for the strategies or projects that they would be most interested in pursuing. Table vii outlines the 6 strategies that attracted most of the votes, in order from most to least votes.

TABLE VII.

Participant-identified strategies to begin implementing a Canadian integrative oncology research agenda, and progress to date

| Identified strategy | Progress to date | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Develop a national network for integrative oncology research and knowledge translation. | Working group members are pursuing opportunities to develop a national network by

|

| 2. | Conduct a needs assessment to explore the unmet needs of patients and providers as they relate to integrative cancer care. | No new projects have been developed to date. |

| 3. | Describe and evaluate existing interdisciplinary, collaborative, and team-based health care models. | A protocol is being developed and will be submitted for funding to conduct a scoping review to explore elements of successful team-based health care models and their relevance to integrative oncology. |

| 4. | Identify relevant outcomes of the integrative oncology approach from the perspective of a range of stakeholders. | A collaborative team, including researchers, educators, and an ethicist, has formed and will meet in 2013 to develop an action plan. |

| 5. | Link health records across established integrative oncology programs to streamline and facilitate research and outcomes measurement. | Building on the scoping review of established models of team-based care (see item 3), there is interest in developing a collaborative pilot study between a hospital-based cancer program and a community-based integrative oncology program to assess the potential of linking health records across these sites to improve patient safety, communication, and satisfaction. |

| 6. | Develop decision-aids to facilitate patient-centered, evidence-based integrative oncology care | Ongoing research funded by the Canadian Breast Cancer Research Alliance has led to the development of an innovative computer-based decision aid to support women with breast cancer to make complementary treatment decisions tailored to their individual clinical situation and their values. The foregoing work will provide a platform for the development of further interactive decision aids to support personalized decisions within a wide variety of clinical populations and issues related to integrative oncology. |

Reflecting on the emergent strategies, participants agreed they represent the action plan or “pilot” initiatives necessary to more clearly define a vision and implement the emerging research agenda. In addition, a clear need was recognized to conduct at least one, if not multiple, scoping type exercises as a component of the action plan to ensure that integrative oncology, as a discipline, can benefit from the extensive literature surrounding interdisciplinary and interprofessional team-based care.

Seven working groups were formed to pursue development of collaborative teams and a detailed action plan: one for each of the 6 strategies outlined in Table vii, and one to further refine the overall emerging research framework. Projects within most strategic areas are being developed, as further detailed in Table vii.

3.3.4. Participant Workshop Evaluation

All participants contributed to an evaluation of the workshop by completing a questionnaire designed for the purpose. Overall, evaluations were positive, with a median rating of 6 of a possible 7 (range: 5–7). All participants indicated that their investment in the day was worthwhile, that the networking was valuable, and that all stakeholder opinions had been equally heard throughout the workshop. Further, most participants felt that the workshop objectives were achieved and that, after the workshop, implementation of a Canadian research agenda is closer. Pre-workshop communication, workshop facilitation, and workshop facilities were likewise highly ranked. A lack of clarity regarding the overall workshop objectives, some duplication of workshop content, and the food served were identified as areas that could have been improved.

4. DISCUSSION

The consensus-building process—including the Delphi survey, stakeholder interviews, and the two-day consensus workshop—facilitated articulation of research priorities within a framework specific to integrative oncology in Canada and production of a preliminary action plan to begin implementing a research agenda. Within integrative oncology, opinions about appropriate leadership, structure, therapies, and funding are many and varied, as evidenced by the diversity in established models in Canada and internationally. The same variety of opinions was evident among the broad group of stakeholders who participated in the consensus-building process. The use of the formal Delphi consensus method allowed for those diverse opinions to be shared and managed within a controlled structure to find the common ground. The result is a set of research priorities within a framework that reflects the needs and perspectives of a spectrum of stakeholders who have a direct interest in the integrative oncology field. Given the diversity of opinions, the achievement of consensus emphasizes the relevance, potential, and need for research within the emergent priority areas to guide Canadian practice and policy in the future.

The identified research priorities and framework are reflective of priorities for integrative oncology internationally, but they are also uniquely Canadian. For example, a similar exercise conducted by the National Institute of Complementary Medicine (Australia) used a 3-round Delphi survey to identify consensus-based priority research priorities. Randomized controlled trials relating to clinical effectiveness (specific to herbal medicine and nutritional supplements) emerged as the top priority, followed by investigation of appropriate knowledge translation strategies and studies relating to the safety of biologic complementary treatments when used alongside conventional cancer treatments12. In an international survey, studies to examine the clinical effectiveness and safety of complementary therapies and appropriate research methods similarly emerged as research priorities13. The Canadian research priorities that materialized through the consensus-building process are focused on integrative and not complementary medicine. That choice was deliberate and reflects an emerging trend in Canada to recognize that complementary therapies are often combined with conventional medical treatments in a shift toward integrative care. Within integrative oncology, high-quality evidence for the safety, effectiveness, and costs of individual therapies is needed, but evidence is also needed to support a safe, effective, and efficient process to combine complementary and conventional treatments14. An integrative oncology research agenda therefore also requires a focus on the unique issues raised in the provision of interdisciplinary team-based care—for example, scope of practice, communication, and infrastructure15. The research framework we propose not only prioritizes research on individual complementary therapies, but also on the means by which those therapies are integrated within a coherent health care system.

Some limitations to our consensus-building approach must be noted. The response rate between rounds 1 and 2 of the Delphi survey was a bit lower than the 70% threshold often quoted as ideal to maintain the rigour of the technique16; however, the rate remained well above the threshold—at 92.3%—between rounds 2 and 3. Reasons for the initial low response rate included an unplanned delay in administering round 2 because of the winter holidays, which likely contributed to decreased momentum among panel members. Illegible e-mail addresses on some round 1 paper-based questionnaires also made follow-up with certain participants impossible. The high response for the follow-up rounds and the broad representation across stakeholder groups within the final panel suggests that a wide range of opinions and perspectives are indeed reflected in the results; however, the current lack of coordination within the integrative oncology field makes it difficult to judge how representative of the broader community of Canadian stakeholders our sample was. Our recruitment strategy focused on two established networks of complementary and integrative oncology experts, which suggests that the stakeholders who participated in our project might hold more positive opinions about the need to advance integrative oncology in Canada than do those who did not participate. However, the proposed research priorities and framework emerged separately from the articulation of a vision and therefore do not attach value to any particular role for integrative oncology in the health care system. Instead, they outline a framework required to guide future decisions about what a potential role might look like. Further work is required to define the level of evidence needed within each of the priority areas to apply research results clinically or to meaningfully affect policy15.

To ensure that integrative oncology research can best guide practice and policy, engagement of the spectrum of Canadian integrative oncology stakeholders is strongly needed. Perhaps most important for ensuring sustainable results is the need to engage stakeholders less familiar with, and perhaps resistant to, complementary therapies and the integrative approach—for example, conventional oncologists and policymakers. In addition to ensuring relevance and acceptability, ongoing stakeholder consultation and engagement will be crucial to ensuring an effective knowledge-to-action process that facilitates the provision of safe and effective care17. Publication of the results of this consensus-building process is intended to help initiate the required engagement by raising awareness of the need to coordinate efforts in such a diverse field and by encouraging related communication and collaborations. The development of a national network related to research and knowledge translation in this field was identified as a key strategy in the implementation of a Canadian research agenda, and members of the icon Research Initiative are actively pursuing that opportunity as a means to address many needs within the integrative oncology field. For example, the network infrastructure could enable the development of meaningful collaborative relationships among diverse stakeholders, groups, and organizations in Canada and could support appropriate knowledge synthesis, dissemination, and exchange. A well-connected network comprising diverse stakeholders, representative of both conventional and complementary health care, would also be well positioned to advocate for the infrastructure and research support required to advance Canadian integrative oncology practice and policy. Finally, over time, such a group could meaningfully contribute to the development of a realistic and feasible vision for integrative oncology in Canada, something that appears impossible at the moment. By definition, integrative oncology is a collaborative exercise, and for that reason, we invite anyone involved in integrative oncology—as a practitioner, researcher, decision-maker, patient, or otherwise—to contact us to comment on the consensus-building process and the results presented here or the action plan moving forward.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Through the consensus-building process reported here, research priorities unique to integrative oncology in Canada were identified and strategies to begin implementing a Canadian integrative oncology research agenda are being pursued. However, to ensure appropriate uptake and implementation, ongoing stakeholder consultation, including engagement from new stakeholders, is needed. Interested individuals are invited to contact the authors with their ideas.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a Meetings, Planning and Dissemination grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and by an in-kind contribution from the Ottawa Integrative Cancer Centre.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Astin JA, Reilly C, Perkins C, Child WL, on behalf of the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation Breast cancer patients’ perspectives on and use of complementary and alternative medicine: a study by the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006;4:157–69. doi: 10.2310/7200.2006.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balneaves LG, Bottorff JL, Hislop TG, Herbert C. Levels of commitment: exploring complementary therapy use by women with breast cancer. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:459–66. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eng J, Ramsum D, Verhoef M, Guns E, Davison J, Gallagher R. A population-based survey of complementary and alternative medicine use in men recently diagnosed with prostate cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2003;2:212–16. doi: 10.1177/1534735403256207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molassiotis A, Fernadez–Ortega P, Pud D, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:655–63. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gansler T, Kaw C, Crammer C, Smith T. A population-based study of prevalence of complementary methods use by cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;113:1048–57. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng GE, Frenkel M, Cohen L, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: complementary therapies and botanicals. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2009;7:85–120. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sagar SM. Integrative oncology in North America. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006;4:27–39. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seely DM, Weeks LC, Young S. A systematic review of integrative oncology programs. Curr Oncol. 2012;19:e436–61. doi: 10.3747/co.19.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, Brook RH. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:979–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.74.9.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMurray AR. Three decision-making aids: brainstorming, nominal group and Delphi technique. J Nurs Staff Dev. 1994;10:62–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leis A, Sagar S, Verhoef M, Balneaves L, Seely D, Oneschuk D. Shifting the paradigm: from complementary and alternative medicine (cam) to integrative oncology. In: Sutcliffe S, Elwood M, editors. Cancer Control. Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 239–58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robotin M, Holliday C, Bensoussan A. Defining research priorities in complementary medicine in oncology. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20:345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melchart D, Ernst E. Priorities for research in complementary medicine. J R Soc Med. 2001;94:608. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1520039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leis AM, Weeks LC, Verhoef MJ. Principles to guide integrative oncology and the development of an evidence base. Curr Oncol. 2008;15(suppl 2):S83–7. doi: 10.3747/co.v15i0.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng G, Weber W, Sood A, Kemper KJ. Research on integrative healthcare: context and priorities. Explore (NY) 2010;6:143–58. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–15. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507865102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tetroe J. Knowledge Translation at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research: A Primer. Austin, TX: U.S. National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research; 2007. Technical Brief No. 18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]