Abstract

Background

Transposable elements (TEs) have the potential to produce broad changes in the genomes of their hosts, acting as a type of evolutionary toolbox and generating a collection of new regulatory and coding sequences. Several TE classes have been studied in Neotropical cichlids; however, the information gained from these studies is restricted to the physical chromosome mapping, whereas the genetic diversity of the TEs remains unknown. Therefore, the genomic organization of the non-LTR retrotransposons Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 in five Amazonian cichlid species was evaluated using physical chromosome mapping and DNA sequencing to provide information about the role of TEs in the evolution of cichlid genomes.

Results

Physical mapping revealed abundant TE clusters dispersed throughout the chromosomes. Furthermore, several species showed conspicuous clusters accumulation in the centromeric and terminal portions of the chromosomes. These TE chromosomal sites are associated with both heterochromatic and euchromatic regions. A higher number of Rex1 clusters were observed among the derived species. The Rex1 and Rex3 nucleotide sequences were more conserved in the basal species than in the derived species; however, this pattern was not observed in Rex6. In addition, it was possible to observe conserved blocks corresponding to the reverse transcriptase fragment of the Rex1 and Rex3 clones and to the endonuclease of Rex6.

Conclusion

Our data showed no congruence between the Bayesian trees generated for Rex1, Rex3 and Rex6 of cichlid species and phylogenetic hypothesis described for the group. Rex1 and Rex3 nucleotide sequences were more conserved in the basal species whereas Rex6 exhibited high substitution rates in both basal and derived species. The distribution of Rex elements in cichlid genomes suggests that such elements are under the action of evolutionary mechanisms that lead to their accumulation in particular chromosome regions, mostly in heterochromatins.

Background

Transposable elements (TEs) have the potential to produce broad changes in the genomes of their hosts [1,2], acting as a type of evolutionary toolbox and generating a collection of new regulatory and coding sequences [3,4], and have the potential to generate biodiversity and evolutionary transitions through lineage-specific mutations and molecular domestication [5]. In addition, TEs can be transferred between reproductively isolated species through horizontal transfer and can trigger a series of events that actively shapes genomic architecture, as for example through illegitimate recombination between TE copies leading to chromosomal duplications, deletions or inversions, providing raw material for adaptive genomic innovations [6].

Based on their structure and transposition mechanisms, mobile genetic elements are divided into two classes: class I includes transposable elements that have RNA as an intermediate (retrotransposons) that is subsequently copied into cDNA by a reverse transcriptase and integrated into a new genomic site; class II includes the transposons that are directly transposed from DNA to DNA without another intermediate molecule [7-10]. Retrotransposons can also be grouped according to presence or absence of long terminal repeats (LTR). LTRs are necessary for cDNA transcription and integration after reverse transcription; these sequences contain domains for proteinase, integrase, reverse transcriptase, and RNAse. Non-LTR retrotransposons use internal promoters for their transposition and encode a reverse transcriptase and RNAse; these retrotransposons are also known as LINEs (long interspersed elements) or TP (target-primed) retrotransposons. Additionally, SINEs (short interspersed nucleotide elements) fall within the non-LTR category; these retrotransposons do not encode the enzymatic machinery necessary for transposition but probably obtain functionality via LINEs [11].

Various transposable elements are found in genomes and the same type of TE can have very different invasive success in diverse species [11]. TEs have been proposed to be involved in the biodiversity and speciation of Teleost fish. Teleost diversity is also reflected in the diversity of their genome size and structure, which have been considerably affected by retroelements [12,13]. All of the previously described retrotransposon types have been observed in fish genomes [14-17], and among the non-LTR retrotransposons, Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 were active during the evolution of teleost fish [16,18,19]. The Rex1 TE is related to the CR1 clade of LINEs and encodes a reverse transcriptase, which is frequently removed by incomplete reverse transcription [18]. Rex3 is related to the RTE family and essential features of the element in fish are (i) coding regions for an endonuclease and a reverse transcriptase, (ii) 5’ truncations of most of the copies, (iii) a 3’ tail consisting of tandem repeats of the sequence GATG, and (iv) short target site sequence duplications of variable length [16]. Rex6 encodes a reverse transcriptase and a putative restriction enzyme-like endonuclease and is a member of the R4 family of non-LTR retrotransposons [16].

Fish belonging to the family Cichlidae (Perciformes) are considered an excellent evolutionary model due to their adaptive radiation and their ecological and behavioral diversity [20,21]. Among the cichlids, only the subfamily Cichlinae is found in the Neotropical region. Analysis combining the morphological and nucleotide sequence characteristics allowed the subfamily Cichlinae to be recovered as monophyletic and partitioned into seven tribes: Cichlini (basal tribe), Retroculini, Astronotini, Chaetobranchini, Geophagini, Cichlasomatini, and Heroini (derived tribe). Chaetobranchini and Geophagini was resolved as the sister group of Heroini and Cichlasomatini. The mono-generic Astronotini was recovered as the sister group of these four tribes. Finally, a clade composed of Cichlini and Retroculini was resolved as the sister group to all other cichlines [22]. To date, 135 species of cichlids have been cytogenetically analyzed, the diploid number of chromosome is predominantly 2n = 48 (more than 60% of the studied species), although variations ranging from 2n = 38 to 2n = 60 have been described. For African species, the modal diploid number of chromosome is 2n = 44. In the other hand, for Neotropical cichlids, the most common chromosome number is 2n = 48, which is considered to be the ancestral characteristic for all cichlids [23,24].

In the Amazon region some species of cichlids are important in recreational and subsistence fishing, aquaculture, and aquarium-hobby, as Cichla monoculus (Cichlini), Astronotus ocellatus (Astronotini), Geophagus proximus (Geophagini), Pterophyllum scalare and Symphysodon discus (Heroini). Cichla species have karyotypes with 2n = 48 subtelo/acrocentric (st/a) chromosomes, few heterochromatin and nucleolus organizer regions located on one chromosome pair [25]. This pattern is described as basal to the Neotropical cichlids [23,26]. Although A. ocellatus, G. proximus and P. leopoldi also have 2n = 48 chromosomes, they differ in karyotype formula, with meta/submetacentric (m/sm) chromosomes due to chromosomal inversions, and accumulation of heterochromatin in the pericentromeric regions [27]. The highest diploid number described for Cichlinae is found in species of the genus Symphysodon, which has 2n = 60 chromosomes, as well as large heterochromatic blocks. These heterochromatic regions are rich in the Rex3 TE that seems to have been active in the karyotype evolution of Symphysodon, being probable involved in translocation events [28].

Several TE classes were cytogenetically mapped on the Neotropical cichlid genome: Tc1 transposons in Cichla kelberi, which showed conspicuous blocks in the centromeric regions and small clusters scattered throughout the chromosomes [29]; RCk, which exhibits clusters scattered throughout the C. kelberi chromosome; AoRex3 and AoLINE, which are clustered in the centromeric heterochromatin of all of the chromosomes of the complement in Astronotus ocellatus[29]; and Rex elements were mapped in few species [28-31]. Furthermore, these findings are restricted to physical chromosome mapping, and the genetic diversity of these retroelements remains unknown.

Rex1, Rex3 and Rex6 are widely distributed among fish genomes, thus enabling comparative analysis among species. Therefore, comparative analyses encompassing basal and derived species are of particular interest for understanding the role of retroelement dynamics in the genomic evolution of new world cichlids. This study aimed to evaluate the genomic organization of three non-LTR retrotransposons, Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6, in five Amazonian cichlids of different tribes, comprising basal and derived species, using the combination of physical chromosome mapping and DNA sequencing in the way to provide information about the role of TEs in the evolution of cichlid genomes.

Results

Physical chromosome mapping of TEs

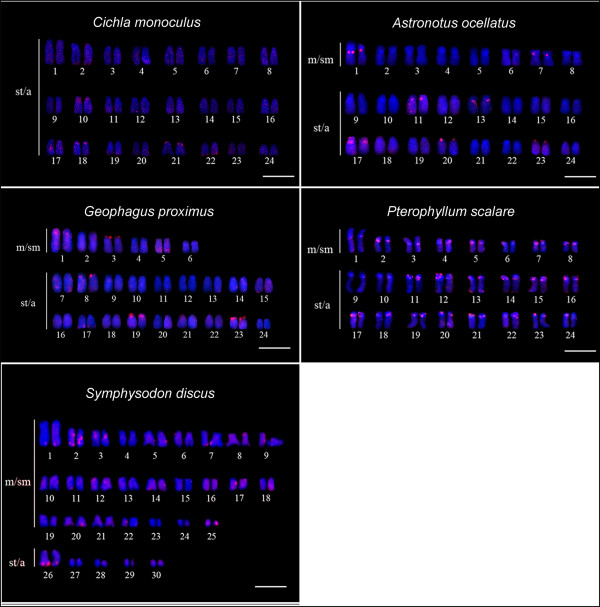

For a better comparison of the physical chromosome location of Rex retroelements in relation to the pattern of constitutive heterochromatin, chromosome distribution of telomeric sequences, and ribosomal sites described for the five species, we followed karyotypic organization recently proposed for these species [27]. The chromosomes were separated into classes (meta/submetacentric – sm/sm, and subtelo/acrocentric – st/a), matched on the basis of hybridization patterns and organized in descending order of size. The Rex1 retroelement was scattered throughout the chromosomes of Cichla monoculus, Astronotus ocellatus, Geophagus proximus, Pterophyllum scalare, and Symphysodon discus. Furthermore, Astronotus ocellatus exhibited pairs 11, 17, and 23 with extensive distribution of this retroelement; similar results were observed for pairs 1, 5, 7, 8, 14, 15, 19, 20, 21 and 23 of Geophagus proximus and for most of the chromosome pairs of Symphysodon discus. However, all the species exhibited more conspicuous clusters in the terminal and/or centromeric regions with more markings in Pterophyllum scalare (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cytogenetic mapping of Rex1 retrotransposon (red signals). Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI. m/sm = meta/submetacentric chromosomes; st/a = subtelo/acrocentric chromosomes. Bar = 10 μm.

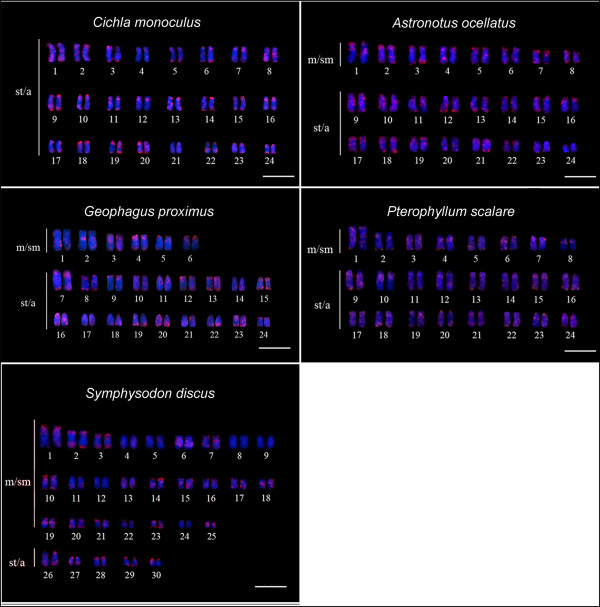

Multiple and intense sites of hybridization were obtained for the Rex3 and Rex6 retroelements in the five species assessed. These TEs appear to have an almost pan-genomic distribution with larger clusters in terminal regions of most chromosomes from the five species, as well as in the centromeric, pericentromeric and interstitial regions. In the other hand, few unlabeled chromosomes were visualized (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Cytogenetic mapping of Rex3 retrotransposon (red signals). Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI. m/sm = meta/submetacentric chromosomes; st/a = subtelo/acrocentric chromosomes. Bar = 10 μm.

Figure 3.

Cytogenetic mapping of Rex6 retrotransposon (red signals). Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI. m/sm = meta/submetacentric chromosomes; st/a = subtelo/acrocentric chromosomes. Bar = 10 μm.

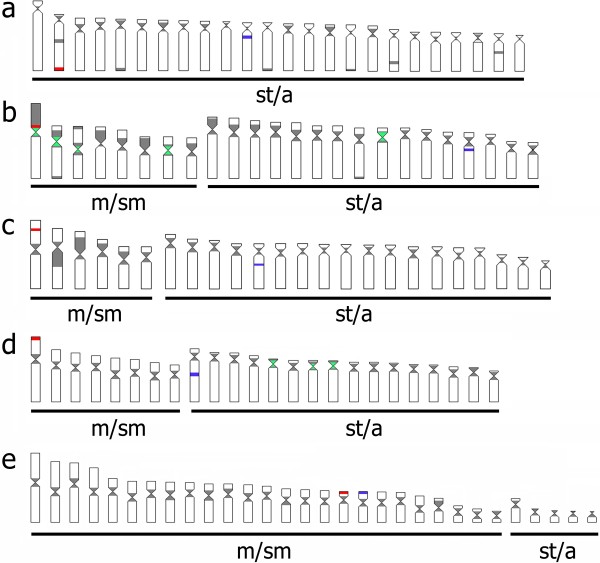

Based in the comparative analysis of the cytogenetic mapping results obtained in the present work with heterochromatin/euchromatin distribution previously published for the same species [25,27-29] it is clear that most Rex clusters are indeed located in heterochromatic chromosomal areas. However, small clusters of Rex1, Rex3 and Rex6, seem also to be located in euchromatic areas (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Representative idiograms of Neotropical cichlid species. (a) C. monoculus, (b) A. ocellatus, (c) G. proximus, (d) P. scalare, (e) S. discus; in gray heterochromatic regions; in red 18S rDNA; in blue 5S rDNA; green, interstitial telomeric sites (ITS).

Molecular diversity of TEs

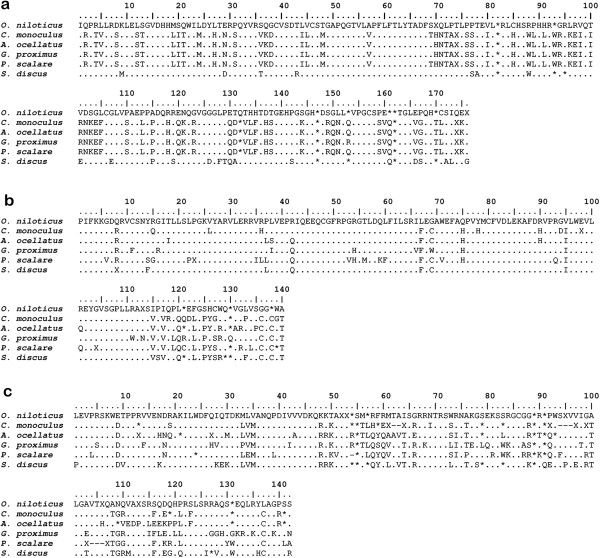

A total of 49 Rex1 clones were sequenced: 11 of C. monoculus, 8 of A. ocellatus, 10 of G. proximus, 12 of P. scalare, and 8 of S. discus. Sequences of 573- to 575-bp (base pairs) long were obtained. Nucleotide substitutions were observed more frequently in the derived species (P. scalare and S. discus) and less so in the basal species (C. monoculus and A. ocellatus). No substitutions were observed in C. monoculus, whereas the following nucleotide substitutions were observed in the other species: 1 transition in A. ocellatus; 2 transitions in G. proximus; 2 transitions and 3 transversions in P. scalare; and 18 transitions, 7 transversions, and 4 indels (insertions/deletions) in S. discus. Compared with the Rex1 sequence of other cichlids available in Genbank, a 91% genetic identity with Hemichromis bimaculatus [GenBank: AJ288479] and a 94% genetic identity with Oreochromis niloticus [GenBank: AJ288473] were observed. It was also possible to identify conserved blocks corresponding to the reverse transcriptase coding region, with corresponding similarity between S. discus and O. niloticus, as well as similarity among the others (Figure 5a). The phylogenetic tree of Rex1 element clones indicated separation between Symphysodon discus and the remaining species, as indicated by two branches (Figure 6). These tree clustering do not reflect the phylogenetic relationship of the species assessed. However, all cichlid Rex1 sequences form a monophyletic group (containing two branches) divergent from the marine Perciformes species. The branch 1: grouped S. discus and Cichlasoma labridens, (both Neotropical cichlids), and form a sister group with Oreochromis niloticus and Hemichromis bimaculatus (African cichlids). The branch 2: encompasses sequences of C. monoculus, A. ocellatus, P. scalare and G. proximus. The average genetic distance between species varied from 0.33 to 0.68% among C. monoculus, A. ocellatus, P. scalare and G. proximus. This value is lower compared to the data detected by comparing these species with S. discus, which ranged from 36.37 to 37.06%. The latter are similar to the average genetic distance between branch 2 (C. monoculus, A. ocellatus, P. scalare and G. proximus) and African cichlids, which ranged from 34.95 to 38.11% (Additional file 1).

Figure 5.

Alignment of aminoacid sequences of TEs among cichlids: a) Rex1 reverse transcriptase domain of analyzed species compared with O. niloticus (accession number AJ288473); b) Rex3 reverse transcriptase domain compared with O. niloticus (accession number AJ400370); c) Rex6 endonuclease domain of analyzed species compared with O. niloticus (accession number AJ293545). Dots indicate similarity in sequence and asterisks indicate stop codons.

Figure 6.

Bayesian tree for reverse transcriptase nucleotide sequences revealing two monophyletic lineages of Rex1 retroelement. Numbers above the branches represent Bayesian posterior probability values. In red Neotropical cichlid species; in blue African cichlid species; in green Perciformes marine species.

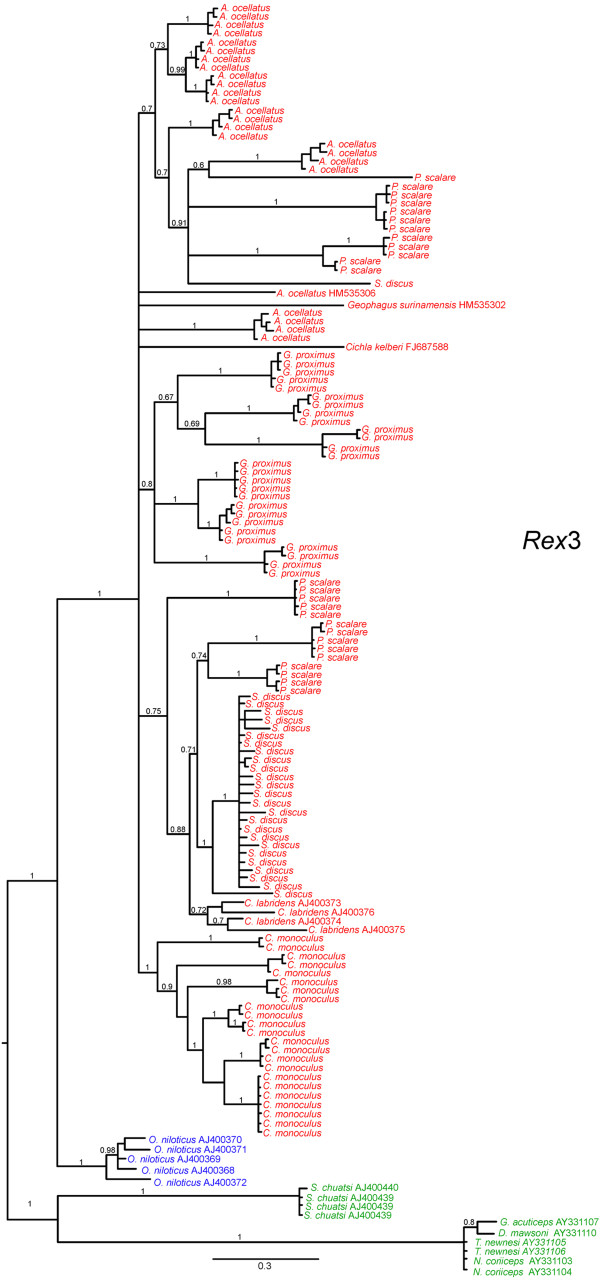

Sequences of 418-475 bp in length were obtained from the 126 Rex3 clones assessed. There were a total of 23 clones of C. monoculus, 24 of A. ocellatus, 27 of G. proximus and 26 clones of P. scalare and S. discus. The Rex3 retroelement was highly variable in all of the species assessed with the following multiple nucleotide substitutions: 114 in C. monoculus (79 transitions, 25 transversions, and 10 indels), 159 in A. ocellatus (83 transitions, 19 transversions, and 57 indels), 215 in G. proximus (89 transitions, 34 transversions, and 92 indels), 242 in P. scalare (130 transitions, 58 transversions, and 54 indels), and 245 in S. discus (133 transitions, 58 transversions, and 54 indels). When compared with Rex3 sequences from other cichlids available in Genbank, an 87% genetic identity with Oreochromis niloticus [GenBank: AJ400370], a 91% genetic identity with Cichla kelberi [GenBank: FJ687588], and a 92% genetic identity with Geophagus surinamensis [GenBank: HM535302] were observed. Even with wide variations in the cloned sequences, it was possible to identify conserved blocks corresponding to the Rex3 reverse transcriptase coding sequence (Figure 5b). Rex3 sequences of marine Perciformes clustered separated from all cichlids species, and O. niloticus (African cichlid) appeared as sister group of the South American cichlids. With exception of C. monoculus, the other species formed paraphyletic branches and were not grouped into exclusive clades (Figure 7). Regarding the genetic distance between species, the values ranged from 6.96 to 16.35% in Neotropical cichlids, values which are close to those found when compared with African cichlids (Additional file 2).

Figure 7.

Bayesian tree for reverse transcriptase nucleotide sequences of Rex3 retroelement. Numbers above the branches represent Bayesian posterior probability values. In red Neotropical cichlid species; in blue African cichlid species; in green Perciformes marine species.

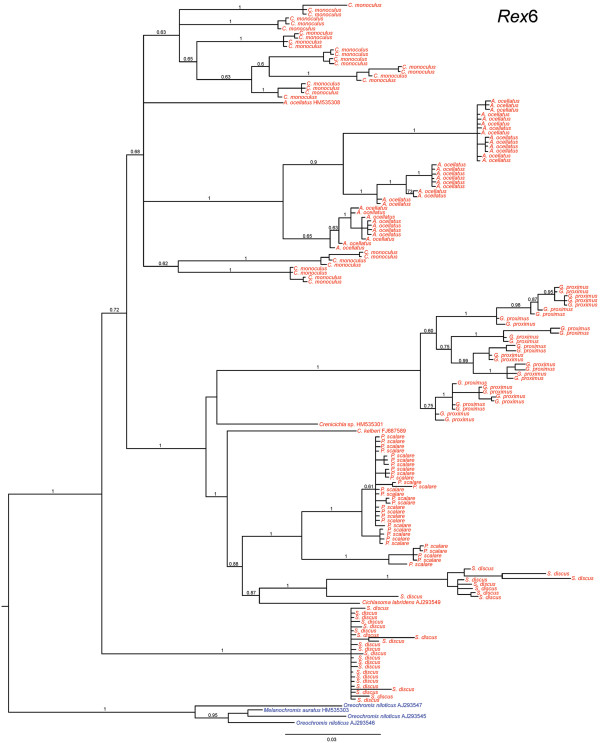

Fragments between 459 and 505 bp in length were generated for the 156 Rex6 retroelement cloned sequences. A total of 30 C. monoculus clones, 34 A. ocellatus clones, 30 G. proximus clones, 30 P. scalare clones, and 32 S. discus clones were sequenced. In addition, C. monoculus and S. discus showed high nucleotide substitution rates: 214 (81 transitions, 63 transversions, and 70 indels) and (103 transitions, 88 transversions, and 23 indels), respectively. Nucleotide substitutions were also observed in the other species: 78 (48 transitions and 19 transversions and 11 indels) in G. proximus, 67 (41 transitions, 17 transversions, and 9 indels) in A. ocellatus and 54 (36 transitions, 7 transversions, and 11 indel) in P. scalare. When compared with the other Rex6 cichlid sequences available in Genbank, the following sequence identities were observed: an 81% identity with Oreochromis niloticus [GenBank: AJ293545], an 83% identity with Melanochromis auratus [GenBank: HM535303], and an 88% identity with Crenicichla sp. [GenBank: HM535301]. The sequences exhibited a region of homology with the Rex6 endonuclease domain (Figure 5c). The pairwise genetic distance between species ranged from 6.52% (between the African species Melanochromis sp. and Oreochromis sp) to 24.63% (observed between Neotropical species A. ocellatus and S. discus) (Additional file 3). The clones of each species were grouped into distinct branches on the phylogenetic tree for the Rex6 element in which A. ocellatus appears grouped of all C. monoculus clones. African cichlids form a sister group to all South American species. All C. monoculus and A. ocellatus clones formed a sister group to the remaining derived species. Geophagus proximus formed a sister group of Crenicichla sp., which is a basal clade to the one that includes P. scalare, S. discus and Cichlasoma labridens. In addition, two lineages of Rex6 are evident in S. discus. One lineage related to sequences of C. labridens and another forming the basal group to the all analyzed species (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Bayesian tree for endonuclease nucleotide sequences of Rex6 retroelement. Numbers above the branches represent Bayesian posterior probability values. In red Neotropical cichlid species; in blue African cichlid species.

Discussion

Chromosomal distribution of TEs clusters

Recent studies have indicated that cichlids have a dynamic karyotype, with variations being observed in the chromosome number, karyotype structure, and in relation to the distribution of repetitive DNA, with differences in the number and location of rDNA sites, presence of interstitial telomeric sites in some taxa and pattern of TEs distribution among species, which vary between dispersed and compartmentalized [24,27,28,31]. Among the repetitive elements, TEs stand out due to their ability to generate evolutionary change through various processes, including gene inactivation, the combining of exons, and gene conversion [for review, see [32]. In addition, ectopic homologous recombination between nonallelic copies of TEs can lead to the formation of deletions, duplications, inversions and translocations, and the process of transposition itself can induce various types of rearrangements at the target site [13]. It has long been known that cryptic and non-autonomous TEs accumulate in heterochromatic regions of the genome, including in fish [27-29,31,33]. However, in certain species, these transposable elements are found in euchromatic regions [28,30,34]. Unlabeled chromosomes visualized for Rex3 and Rex6 suggests that the TEs could have been lost due to molecular processes that erode repetitive DNA sequences, or to the presence of few TE residues could have escaped detection by FISH. All specimens here investigated had their heterochromatic pattern previously described [27] and presented accumulation of Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 clusters mostly in heterochromatic regions, but small clusters were also detected in euchromatic areas. This result indicates at least two hypotheses: i) the chromosomal distribution of these TEs can be driven by particular evolutionary mechanisms and may evolve differentially from other repetitive sequences commonly present in the heterochromatin; ii) these TEs could have acquired structural/regulatory functions and their movement to euchromatic regions could bring advantage to the host genome or have been maintained according to neutral mechanisms.

The movement and accumulation of TEs has a great influence of host genomes, and it is becoming clear that TEs form part of the regulatory toolkit of the genome and play important roles in controlling gene expression [35,36], although the relationship between TEs and regulatory function is not always straightforward and easily visualized. Nevertheless, correlation between karyotypic rearrangements and retrotransposon activity was observed in the marine Perciformes, for which compartmentalized distribution with accumulation in the pericentromeric regions is observed among the derived species, such as Notothenia coriiceps[37].

Chromosomal rearrangements are evident in Cichlinae evolution, and interstitial telomeric sites (ITS) are recognized in Astronotus ocellatus[27]. These ITS are probably associated with various classes of repetitive DNA, and these TEs may have possibly acted in the chromosomal rearrangements of A. ocellatus because the retroelements Rex1, 3, and 6 appear in the same chromosomal regions where the ITSs were observed [27]. The accumulation of TEs in particular genomic regions of cichlids has been associated to possible events of chromosome rearrangements [28-31,38].

TEs can insert into virtually any portion of the host genome; however, certain preferred insertion regions have already been reported, such as in ribosomal genes [39,40]. An association between Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 and the 18S and 5S ribosomal sites was observed in all of the species assessed in this study. This association between TE and rDNA in cichlids may have had a role in the generation of multiple 18S rDNA sites found in P. scalare[27] and the 18S rDNA site variability observed in Symphysodon aequifasciatus[41]. Analysis of the 18S rRNA gene distribution in the Oreochromis niloticus genome reveals that 18S copies are always surrounded by TEs, suggesting that such elements could be acting in the dispersion of 18S copies generating higher number of clusters and sites variability [42].

Diversity and evolution of Rex1, Rex3 and Rex6 TEs

Although little is known about the genomic evolution and the effects of retroelements in fish, these elements appear to be responsible for the karyotype dynamism that has been recently revealed in cichlids [23,24,27,28,30]. This dynamism is also exemplified by an examination of Neotropical cichlid TE sequences. Rex1 exhibited two evolutionary lineages, even being the most conserved TE with few nucleotide substitutions. High values of genetic distance were found for Rex1 among Neotropical species (C. monoculus, A. ocelatus, G. proximus and P. scalare) and (C. labridens and S. discus). But the genetic distance was lower when compared S. discus (Neotropical species) and O. niloticus (African species).

The presence of various Rex1 lineages has been observed previously in fish genomes with four reported lineages for this retroelement [18]. The clones assessed in this study correspond to lineage 4, which is commonly observed in the genome of fish from superorder Acanthopterygii [18].

The emergence of lineages may be the result of the frequent loss or rapid divergence of these retroelements [43]. In addition, the high level of similarity among the Rex sequences of some teleost fish species suggests relatively recent activity of this retroelement [19]. However, the Rex sequences of cichlids showed a high degree of variability and Rex3 showed a paraphiletic Bayesian tree that does not reflect the phylogeny proposed for the group. In this case, probably several Rex3 strains invaded the genome of these species and have been retained, with gain and loss of sequences within each species. Furthermore, the presence of stop codons in the TE aminoacid sequences suggests that these sequences correspond to inactive elements. If considered the group evolutionary history, perhaps Rex TEs have acted shaping karyotypes, but are no longer active. This fact can be reinforced because it is possible to observe conserved blocks corresponding to the reverse transcriptase domain of Rex1 and Rex3 and to the endonuclease for Rex6.

Rex1 and Rex3 nucleotide sequences were more conserved in the basal species (C. monoculus) than in the derived species (S. discus). This result is possibly associated with the selective forces that tend to stabilize the genome, which frequently eliminates TE families from the genome of some species [11], as the repression mechanisms in each host may be different [44]. Furthermore, the genomic evolution of Symphysodon is complex and involves hybridization events among the species [45], which may have caused instability in the TEs and led to transposition events that resulted in multiple chromosomal rearrangements [28]. In contrast, Rex6 exhibited high substitution rates in C. monoculus (basal clade) that were similar to those observed in S. discus (derived). Rex6 presents a remarkable characteristic with two clearly defined subfamilies in S. discus. The accumulation of mutations may be associated with TE senescence, which is usually characterized by an accumulation of mutations followed by the probable stochastic loss of the element [46].

Studies have demonstrated that TE sequences evolve independently in the genomes of their hosts [47,48], and this evolutionary pattern can be a consequence of horizontal transfer, which causes incongruence between the host and TE phylogenies [49]. In this view, the phylogenetic trees of Rex1, Rex3 and Rex6 do not reflect the species phylogenetic tree [22], and it is likely that horizontal transfer events occurred in these retroelements during the evolutionary history of the species that were assessed. Although previous studies have suggested that Rex elements could have suffered the action of horizontal transfer [30,37], ancestral polymorphism and different TE evolutionary rates among the hosts, including loss and gain of TE copies, cannot be disregarded. Although advances in undertanding the evolutionary dynamics of TEs in cichlids have been achieved, the increase in sampling species and sequences is still necessary to have a better view of the organization and function of TEs in the fish genomes.

Conclusions

The distribution of Rex elements in cichlid genomes suggest that such elements are under the constraining of evolutionary mechanisms that lead to their accumulation in particular chromosome regions (mostly in heterochromatins). There was no congruence between the trees generated in this study based on TEs and proposed phylogenetic hypothesis for the group, suggesting that horizontal transfer, emergence or elimination of specific TE lineages, could have had important effects in the evolutionary history of Rex elements in the cichlid genomes.

Methods

Specimens belonging to four Cichlidae tribes of the subfamily Cichlinae from the central Amazon region were analyzed. The tribes included Cichlini: Cichla monoculus (3 males and 3 females), Astronotini: Astronotus ocellatus (3 males and 5 females), Geophagini: Geophagus proximus (2 males and 3 females), and Heroini: Pterophyllum scalare (3 males and 3 females) and Symphysodon discus (2 males and 2 females). The tribes sampled include basal and derived clades [22]. The specimens were caught in the wild with sampling permission (ICMBio SISBIO 10609-1/2007). Basic kayotypic analyses with the same s species were previously conducted to describe the diploid number, karyotype formula, pattern of constitutive heterochromatin distribution, number and location of ribosomal sites and sequences telomeric [27].

Chromosomes preparation

Mitotic chromosomes were obtained from kidney cells using an air drying protocol [50], that consists in injecting intraperitoneally colchicine 0.0125% in the proportion of 1 mL per 100 g of animal weight. After 40 minutes the specimens were killed by immersion in ice water and the anterior portion of the kidney was removed, and transferred to a plate with 8 mL of hypotonic solution of 0.075 M KCl. The tissue was disaggregated with a glass syringe and the supernatant (cell suspension) was transferred to a centrifuge tube and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The suspension was pre-fixed with 6 drops of Carnoy fixative (methanol: acetic acid 3:1) and resuspended. After 5 minutes, itwas added 8 mL of Carnoy and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 900 rpm. The supernatant was discarded and 6 mL of Carnoy was added. The material was resuspended and again centrifuged for 10 minutes at 900 rpm, and this wash was repeated twice. After the last centrifugation and removal of supernatant, 1.5 mL of fixative was added and the material carefully resuspended. The cell suspension was then stored in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube and stored in a freezer at -20°C.

DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification

Total DNA was extracted from muscle tissue using phenol-chloroform [51] and quantified in a NanoVue Plus spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications of the retroelements were conducted using the primers RTX1-F1 (5’-TTC TCC AGT GCC TTC AAC ACC-3’) and RTX1-R1 (5’-TCC CTC AGC AGA AAG AGT CTG CTC-3’) to amplify the Rex1 segments corresponding to the coding domains of the reverse transcriptase gene [18]; the primers RTX3-F3 (5’-CGG TGA YAA AGG GCA GCC CTG-3’) and RTX3-R3 (5’-TGG CAG ACN GGG GTG GTG GT-3’) were used to amplify the coding domains of the reverse transcriptase gene of the Rex3 retrotransposon [16]; the primers Rex6-Medf1 (5’-TAA AGC ATA CAT GGA GCG CCA C-3’) and Rex6-Medr2 (5’-GGT CCT CTA CCA GAG GCC TGG G-3’) were designed to amplify the C-terminal part of the endonuclease domain of the Rex6 retrotransposon [19]. All primers were first described for Xiphophorus maculatus. The PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 25 μL containing genomic DNA (200 ng), 10x buffer with 1.5 mM magnesium, Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μL), dNTPs (1 mM), primers (5 mM), and Milli-Q water. The cycling conditions for the Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 reactions included the following steps: 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 2 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were analyzed using electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels, quantified in a spectrophotometer NanoVue Plus (GE Healthcare) and used for cloning and as probes to perform FISH.

Cloning, sequencing and sequence analysis

The PCR products of the retrotransposon elements Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 were inserted in the plasmid pGEM-T Easy (Promega). Ligation products were transformed into DH5α Escherichia coli competent cells. Clones carring the insert of interest were sequenced on an ABI 3130 XL DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer), and the resulting sequences were submitted to the NCBI database under the following accession numbers: Rex1, GenBank: JX576302-JX576350; Rex3, GenBank: JX576351-JX576400; KF131681-KF131756; and Rex6, GenBank: JX576401-JX576459; KF131757-KF131853. Each clone was used as a query in BLASTn searches against the NCBI nucleotide collection (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and the searches against the Repbase [52] at the Genetic Information Research Institute (Giri) (http://www.girinst.org/repbase/) using CENSOR software [53]. Nucleotide sequences were aligned using the ClustalW program package [54] implemented in the BioEdit 7.0 program package [55]. A Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was conducted using MrBayes 3.2 [56]. For this analysis, Markov Chain Monte-Carlo sampling was conducted every 20000th generation until the s.d. of split frequencies was <0.01. A burn-in period equal to 25% of the total generations was required to summarize the parameter values and trees. Parameter values were assessed based on 95% credibility levels to ensure the analysis had run for a sufficient number of generations. For Bayesian analysis, sequences of the Rex1, Rex3, and Rex6 retroelements of all Perciformes (corresponding to the TE segment isolated for cichlids by PCR), available in GenBank, were included. To estimate divergence between species, a genetic distance matrix was constructed using the MEGA5 program and Kimura-2 parameter model [57]. Aminoacid sequences were deduced from nucleotide sequences using BioEdit 7.0 program package [49].

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

The retroelements (Rex1, 3, and 6) were labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Dig- Nick Translation mix; Roche) by nick translation according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and anti-digoxigenin rhodamine (Roche) antibody was used to detect the probe signal. Homologs and heterologs fluorescence in situ hybridizations were carried with 77% stringency (2.5 ng/μL of DNA, 50% deionized formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, and 2x SSC at 37°C for 18 h) [58]. The chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI (2 mg/ml) in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector). Four slides and a minimum of 30 metaphases were analyzed per species.

Microscopy/image processing

Chromosomes were analyzed in objective of 100x using an Olympus BX51 epifluorescence microscope, and the images were captured with a digital camera (Olympus DP71) using the Image-Pro MC 6.3 software. Mitotic metaphases were processed in Adobe Photoshop CS3 program, and the chromosomes were measured using Image J. Karyotypes were arranged in order of decreasing chromosome size [59].

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CHS, MCG and MLT collected the samples, collaborated on all genetic procedures, undertook the bibliographic review, and coordinated the writing of this paper. EJC participated in developing the laboratory techniques performed cloning of TEs. CM and EF coordinated the study, participated in its design and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Kimura-corrected average pairwise distances (intersection between line and column) between aligned sequence of Rex1 partial reverse transcriptase sequences from Cichlids and Perciformes marine species. Above diagonal, average genetic distance within species.

Kimura-corrected average pairwise distances (intersection between line and column) between aligned sequence of Rex3 partial reverse transcriptase sequences from Cichlids and Perciformes marine species. Above diagonal, average genetic distance within species.

Kimura-corrected average pairwise distances (intersection between line and column) between aligned sequence of Rex6 partial endonuclease from Neotropical and African species. Above diagonal, average genetic distance within species.

Contributor Information

Carlos Henrique Schneider, Email: schneider.carloshenrique@gmail.com.

Maria Claudia Gross, Email: m.claudia.gross@gmail.com.

Maria Leandra Terencio, Email: leandrabio2@gmail.com.

Edson Junior do Carmo, Email: edsonjuniorbio@yahoo.com.br.

Cesar Martins, Email: cmartins@ibb.unesp.br.

Eliana Feldberg, Email: feldberg@inpa.gov.br.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa and Desenvolvimento Tecnológico (CNPq 140816/2009-7 CHS scholarship), Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia/Biologia de Água Doce e Pesca Interior (INPA/BADPI), Fundação de Amparo de Pesquisas do Amazonas (PRONEX FAPEAM/CNPq 003/2009), Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 2009/05234-4) and the Center for Studies of Adaptation to Environmental Changes in the Amazon (INCT ADAPTA, FAPEAM/CNPq 573976/2008-2).

References

- Kidwell MG, Lisch DR. Transposable elements and host genome evolution. Tree. 2000;15:95–98. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01817-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell MG, Lisch DR. Perspective: transposable elements, parasitic DNA, and genome evolution. Evolution. 2001;55:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JN. Turning junk into gold: domestication of transposable elements and the creation of new genes in eukaryotes. Bioessays. 2006;28:913–922. doi: 10.1002/bies.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque G, Leong B, Vega VB, Chen X, Lee YL, Srinivasan KG, Chew JL, Ruan Y, Wei CH, Ng HH, Liu ET. Evolution of the mammalian transcription factor binding repertoire via transposable elements. Genome Res. 2008;18:1752–1762. doi: 10.1101/gr.080663.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blass E, Bell M, Boissinot S. Accumulation and rapid decay of non-LTR retrotransposons in the genome of the three-spine stickleback. Genome Biol Evol. 2012;4:687–702. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaack S, Gilbert C, Feschotte C. Promiscuous DNA: horizontal transfer of transposable elements and why it matters for eukaryiotic evolution. Trends Ecol Evol. 2010;25:537–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sluys MA, Scortecci KC, Costa APP. In: Biologia Molecular e Evolução. Matioli SR, editor. São Paulo: Holos Editora; 2001. O genoma instável, sequências genéticas móveis; pp. 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tafalla C, Estepa A, Coll JM. Fish transposons and their potential use in aquaculture. J Biotechnol. 2006;123:397–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins C. In: Fish cytogenetics. Pisano E, Ozouf-Costaz C, Foresti F, Kappor BG, editor. Enfield: Science Publisher; 2007. Chromosomes and repetitive DNA: a contribution to the knowledge of the fish genome; pp. 421–453. [Google Scholar]

- Levin HL, Moran JV. Dynamic interactions between transposable elements and their hosts. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:615–627. doi: 10.1038/nrg3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhne A, Brunet F, Galiana-Arnoux D, Schultheis C, Volff JN. Transposable elements as drivers of genomic and biological diversity in vertebrates. Chromosome Res. 2008;16:203–215. doi: 10.1007/s10577-007-1202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JF, Bouneau L, Ozouf-Costaz C, Fischer C. Diversity of retrotransposable elements in compact pufferfish genomes. Trends Genet. 2003;19:674–678. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JN. Genome evolution and biodiversity in teleost fish. Heredity. 2005;94:280–294. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada N, Hamada M, Ogiwara I, Ohshima K. SINEs and LINEs share common 39 sequences: a review. Gene. 1997;205:229–243. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulter R, Butler M, Ormandy J. A LINE element from the pufferfish (fugu) Fugu rubripes which shows similarity to the CR1 family of non-LTR retrotransposons. Gene. 1999;227:169–179. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00600-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JN, Korting C, Sweeney K, Schartl M. The non-LTR retrotransposon Rex3 from the fish Xiphophorus is widespread among teleosts. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:1427–1438. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio S, Chapman J, Stupka E, Putnam N, Chia JM, Dehal P. et al. Whole genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science. 2002;297:1301–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.1072104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JN, Korting C, Schartl M. Multiple lineages of the non-LTR retrotransposon Rex1 with varying success in invading fish genomes. Mol Bio Evol. 2000;17:1673–1684. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JN, Körting C, Froschauer A, Sweeney K, Schartl M. Non-LTR retrotransposons encoding a restriction enzyme-like endonuclease in vertebrates. J Mol Evol. 2001;52:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s002390010165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher TD. Adaptive evolution and explosive speciation: the cichlid fish model. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:288–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Fernández H, Honeycutt RL, Winemiller KO. Molecular phylogeny and evidence for an adaptive radiation of geophagine cichlids from South America (Perciformes: Labroidei) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;34:227–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WL, Chakrabarty P, Sparks JS. Phylogeny, taxonomy, and evolution of Neotropical cichlids (Teleostei: Cichlidae: Cichlinae) Cladistics. 2008;24:625–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00210.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldberg E, Porto JIR, Bertollo LAC. In: Fish adaptation. Val AL, Kapoor BG, editor. Enfield, USA: Science Publishers; 2003. Chromosomal changes and adaptation of cichlid fishes during evolution; pp. 285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Poletto AB, Ferreira IA, Cabral-de-Mello DC, Nakajima RT, Mazzuchelli J, Ribeiro HB, Venere PC, Nirchio M, Kocher TD, Martins C. Chromosome differentiation patterns during cichlid fish evolution. BMC Genet. 2010;11:50–62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-11-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves-Brinn MN, Porto JIR, Feldberg E. Karyological evidence for interspecific hybridization between Cichla monoculus and C. temensis (Perciformes, Cichlidae) in the Amazon. Hereditas. 2004;141:252–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.2004.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brum MJI. In: Séries Monografias. Sociedade Brasileira de Genética. Ribeirão Preto SP, editor. Brasil: Sociedade Brasileira de Genética; 1995. Correlações entre a filogenia e a citogenética dos peixes Teleósteos; pp. 2–5-42. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CH, Gross MC, Terencio ML, Artoni RF, Vicari MR, Martins C, Feldberg E. Chromosomal evolution of Neotropical cichlids: the role of repetitive DNA sequences in the organization and structure of karyotype. Rev Fish Biol Fisher. 2013;23:201–214. doi: 10.1007/s11160-012-9285-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross MC, Schneider CH, Valente GT, Porto JIR, Martins C, Feldberg E. Comparative cytogenetic analysis of the genus Symphysodon (Discus Fishes, Cichlidae): chromosomal characteristics of retrotransposons and minor ribosomal DNA. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2009;127:43–53. doi: 10.1159/000279443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzuchelli J, Martins C. Genomic organization of repetitive DNAs in the cichlid fish Astronotus ocellatus. Genetica. 2009;136:461–469. doi: 10.1007/s10709-008-9346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira WG, Ferreira IA, Cabral-de-Mello DC, Mazzuchelli J, Valente GT, Pinhal D, Poletto AB, Venere PC, Martins M. Organization of repeated DNA elements in the genome of the cichlid fish Cichla kelberi and its contributions to the knowledge of fish genomes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2009;125:224–234. doi: 10.1159/000230006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente GT, Mazzuchelli J, Ferreira IA, Poletto AB, Fantinatti BEA, Martins C. Cytogenetic mapping of the retroelements Rex1, Rex3 and Rex6 among cichlid cish: new insights on the chromosomal distribution of transposable elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;133:34–42. doi: 10.1159/000322888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazazian HH Jr. Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution. Science. 2004;303:1626–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1089670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C, Bouneau L, Coutanceau JP, Weissenbach J, Volff JN, Ozouf-Costaz C. Global heterochromatic colocalization of transposable elements with minisatellites in the compact genome of the pufferfish Tetraodon nigroviridis. Gene. 2004;336:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terencio ML, Schneider CH, Gross MC, Nogaroto V, Almeida MC, Artoni RF, Vicari MR, Feldberg E. Influence of repetitive sequences in the evolution of the W chromosome in fish of the family Prochilodontidae. Genetica. 2012;140:505–512. doi: 10.1007/s10709-013-9699-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield J. The ecology of the genome-mobile DNA elements and their hosts. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;5:128–136. doi: 10.1038/nrg1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin RK, Martienssen R. Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:272–285. doi: 10.1038/nrg2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozouf-Costaz C, Brandt J, Körting C, Pisano E, Bonillo C. Genome dynamics and chromosomal localization of the non-LTR retrotransposons Rex1 and Rex3 in Antarctic fish. Antarct Sci. 2004;16:51–57. doi: 10.1017/S0954102004001816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira IA, Poletto AB, Kocher TD, Mota-Velasco JC, Penman DJ, Martins C. Chromosome evolution in African cichlid fish: contributions from the physical mapping of repeated DNAs. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2010;129:314–322. doi: 10.1159/000315895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Eickbush TH. Dong, a non-long terminal repeat (non-LTR) retrotransposable element from Bombyx mori. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1318. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.5.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M, Matoso DA, Vicari MR, De Almeida MC, Margarido VP, Artoni RF. Physical mapping of 5S rDNA in two species of Knifefishes: Gymnotus pantanal and Gymnotus paraguensis (Gymnotiformes) Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;134:303–307. doi: 10.1159/000328998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross MC, Schneider CH, Valente GT, Martins C, Feldberg E. Variability of 18S rDNA locus among Symphysodon fishes: chromosomal rearrangements. J Fish Biol. 2010;76:1117–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima RT, Cabral-de-Mello DC, Valente GT, Venere PC, Martins C. Evolutionary dynamics of rRNA gene clusters in cichlid fish. BMC Evol Biol. 2012;12:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzic A, Capy P. In: Transposons and dynamic genome. Lankenau DH, Volff JN, editor. Berlin: Springer Verlag Berlin Heidelberg; 2006. Theoretical approaches to the dynamics of transposable elements in genomes, populations, and species; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Capy P, Login T, Bigot Y, Brunet F, Daboussi MJ, Periquet G, David J, Hartl D. Horizontal transmission versus ancient origin: mariner in the witness box. Genetica. 1994;93:161–170. doi: 10.1007/BF01435248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amado MV, Farias IP, Hrbek T. A molecular perspective on systematics, taxonomy and classification amazonian discus fishes of the genus Symphysodon. Int J Evol Biol. 2011;1:16. doi: 10.4061/2011/360654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsker W, Haring E, Hagemann S, Miller WJ. The evolutionary life history of P transposons: From horizontal invaders to domesticated neogenes. Chromosoma. 2001;110:148–158. doi: 10.1007/s004120100144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerat E, Biémont C, Capy P. Codon usage and the origin of P elements. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:467–468. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerat E, Capy P, Biémont C. Codon usage by transposable elements and their host genes in five species. J Mol Evol. 2002;54:625–637. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-0059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JC, Kidwel MG. Horizontal transfer and selection in the evolution of P elements. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:1542–1557. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertollo LAC, Takahashi CS, Moreira Filho O. Cytotaxonomic considerations on Hoplias lacerdae (Pisces, Erythrinidae) Braz J Genet. 1978;1:103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. New York: Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Pavlicek A, Klonowski P, Kohany O, Walichiewicz J. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohany O, Gentles AJ, Hankus L, Jurka J. Annotation, submission and screening of repetitive elements in Repbase: Repbase submitter and censor. BMC Bioinforma. 2006;7:474. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higging DG, Gibson TJ. ClustalW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/96/NT. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkel D, Straume T, Gray JW. Cytogenetic analysis using quantitative, high-sensitivity, fluorescence hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2934–2938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levan A, Fredga K, Sandberg AA. Nomenclature for centromeric position on chromosomes. Hereditas. 1964;52:201–220. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Kimura-corrected average pairwise distances (intersection between line and column) between aligned sequence of Rex1 partial reverse transcriptase sequences from Cichlids and Perciformes marine species. Above diagonal, average genetic distance within species.

Kimura-corrected average pairwise distances (intersection between line and column) between aligned sequence of Rex3 partial reverse transcriptase sequences from Cichlids and Perciformes marine species. Above diagonal, average genetic distance within species.

Kimura-corrected average pairwise distances (intersection between line and column) between aligned sequence of Rex6 partial endonuclease from Neotropical and African species. Above diagonal, average genetic distance within species.