Abstract

Background

The systemic surveillance of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (IRAB) from multicenters in Taiwan revealed the emergence of isolates with blaOXA-72. This study described their genetic makeup, mechanism of spread, and contribution to carbapenem resistance.

Methods

Two hundred and ninety-one non-repetitive isolates of A. baumannii were collected from 10 teaching hospitals from different geographical regions in Taiwan from June 2007 to September 2007. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by agar dilution. Clonality was determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Plasmid was extracted and digested by restriction enzymes, and subsequently analyzed by electrophoresis and Southern blot for blaOXA-72. The flanking regions of blaOXA-72 were determined by inverse PCR. The contribution of blaOXA-72 to imipenem MIC was determined by transforming plasmids carrying blaOXA-72 into imipenem-susceptible A. baumannii.

Results

Among 142 IRAB in Taiwan, 27 harbored blaOXA-72; 22 originated from Southern Taiwan, 5 from Central Taiwan, and none from Northern Taiwan. There were two major clones. The blaOXA-72 was identified in the plasmids of all isolates. Two genetic structures flanking plasmid-borne blaOXA-72 were identified and shared identical sequences in certain regions; the one described in previous literature was present in only one isolate, and the new one was present in the remaining isolates. Introduction of blaOXA-72 resulted in an increase of imipenem MIC in the transformants. The overexpression of blaOXA-72 mRNA in response to imipenem further supported the contribution of blaOXA-72.

Conclusions

In conclusion, isolates with new plasmid-borne blaOXA-72 were found to be disseminated successfully in Southern Taiwan. The spread of the resistance gene depended on clonal spread and dissemination of a new plasmid. BlaOXA-72 in these isolates directly led to their imipenem-resistance.

Keywords: Imipenem-resistant, Acinetobacter baumannii, Carbapenemase, BlaOXA-72

Background

Acinetobacter baumannii has become an important nosocomial pathogen throughout the world because of its drug resistant phenotype [1]. The resistance to carbapenems is the most troublesome due to a limited number of efficacious drugs and the association with poor prognosis [2]. The mortality associated with imipenem-resistant A. baumannii (IRAB) is higher than that caused by susceptible strains, which is attributable to the higher rate of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy [3,4]. Although modification of antibiotic targets, overexpression of efflux pumps, and loss of porins leads to carbapenem resistance, the main mechanism in the Acinetobacter species is production of carbapenemases, including Ambler class B metallo-β-lactamases and class D β-lactamases [5]. Compared with other Acinetobacter species, class D β-lactamases in A. baumannii, including the intrinsic blaOXA-51-like as well as acquired blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-24-like, blaOXA-58-like, and blaOXA-143 genes are more commonly identified as the cause of resistance [5,6]. The distribution of class D β-lactamases varies among countries, even among regions in the same country [7]. Isolates with blaOXA-23 spread over a wide geographical range [8], whereas those carrying blaOXA-24, though relatively less common, have emerged in France, Italy, South Korea, and Brazil [9-12]. In Taiwan, one pilot study described the spread of isolates with blaOXA-72, a member of the blaOXA-24 family, within a single medical center [13]. Thus, in this study, we collected clinical isolates of A. baumannii from 10 medical centers in different areas in Taiwan during 2007 and found the different geographic distribution of isolates carrying blaOXA-24/72. Therefore, this multicenter study aimed to describe their genetic makeup, mechanism of spread, and contribution to carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii in Taiwan.

Methods

Bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Two hundred and ninety-one non-repetitive isolates of A. baumannii were retrospectively collected from 10 teaching hospitals from different geographical regions in Taiwan from June 2007 to September 2007. Four hospitals are located in Northern (N1-N4) Taiwan, 3 are located in Central (C1-C3) Taiwan, and 3 are located in Southern (S1-S3) Taiwan (Additional File 1). All isolates were taken as part of standard patient care and investigators retrospectively collected these isolates. This microbiological study without patient data was exempt from full review by our institutional review boards.

All isolates were identified to the species level using a multiplex PCR method to confirm the specific intergenic spacer region in A. baumannii[14]. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of imipenem, meropenem, ticarcillin, piperacillin, ceftazidime, cefepime, sulbactam, ciprofloxacin, and colistin was determined using the agar dilution method according to the guidelines provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [15]. The testing and interpretation were in accordance with the guidelines of CLSI breakpoints or manufacturer’s instructions. A. baumannii isolates that were resistant to imipenem were subjected to the experiments described below.

Identifying Ambler class B metallo-β-lactamases and class D β-lactamases

PCR methods were used to detect blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-24-like, blaOXA-58-like, blaISAba1-OXA51-like, blaOXA-143,blaIMP-like, blaVIM-like, blaGIM-1, blaSPM-1 and blaSIM-1 as previously described [6,16,17]. The PCR products were then sequenced at Mission Biotech, Taipei, Taiwan. Primers of ISAba1F and ISAba1R were used to detect the presence of ISAba1, whereas the ISAba1F and OXA-likeR primers against the different genes described above were used to confirm the presence of ISAba1 upstream of the carbapenemase gene [16].

Determination of clonality by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of isolates with blaOXA-72

The clonality of strains with blaOXA-72 was determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis after digestion with ApaI as previously described [18]. The stained gel was photographed and analyzed by BioNumerics software (Applied Maths) to generate a dendrogram of relatedness among these isolates. Isolates with similarity > 85% was designated as one clone.

Determination of the plasmid localization of blaOXA-72 by Southern blot

The plasmid localization of blaOXA-72 was visualized as previous reported [19]. The plasmid was extracted with a plasmid DNA Miniprep Kit (Bioman, Taipei, Taiwan) or a plasmid Maxiprep Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The extracts were treated with EcoRI and subjected to electrophoresis. After transfer to the hybridization transfer membrane (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) and hybridization with a PCR-generated probe derived from primers targeting blaOXA-72 (Additional File 2), the band was visualized with a digoxigenin (DIG) DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequencing of flanking region of plasmid-borne blaOXA-72 by inverse PCR

Inverse PCR was performed as previously reported [20]. Briefly, the plasmid extracted from isolates carrying blaOXA-72 was digested with EcoRI, HindIII, or BglII, respectively. After overnight incubation and subsequent purification, T4 DNA ligase (Promega Corp., Madison, USA) was added in each extract according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Outward amplification with PCR primers (Additional File 2) covering portions of the blaOXA-72 region was carried out under standard conditions. The product was then sent for sequencing at Mission Biotech, Taipei, Taiwan.

Determination of the contribution of blaOXA-72 to carbapenem MIC

The blaOXA-72 was cloned into the shuttle vector pYMAb2 [21], which carries a kanamycin resistant determinant. The recombinant plasmid (pYMAb2:: blaOXA-72) and control plasmid (pYMAb2) were then transformed into the kanamycin-susceptible Ab290 strain by electroporation using an gene pulser electroporator (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and 2 mm electrode gap cuvettes. The antimicrobial MICs of Ab290 (pYMAb2:: blaOXA-72) and Ab290 (pYMAb2) were determined as previously described [15]. Ab290 was an A. baumannii clinical isolate that was susceptible to multiple antimicrobial agents from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and has been used for transformation in the previous study [19]. After incubation without or with antimicrobial agents, the OXA-72 mRNAs in Ab290 (pYMAb2:: blaOXA-72) were compared using quantitative PCR [21]. Briefly, bacterial RNA was extracted using an RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent and RNeasy mini-kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). After elimination of genomic DNA by RNase-free DNase (Qiagen) treatment, reverse transcription was performed using random hexamers (Qiagen). Real-time PCR for blaOXA-72 was carried out with recA as an internal control on an ABI 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) These experiments were performed in at least triplicate.

Results

Bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

One-hundred and forty-two A. baumannii strains were resistant to imipenem. Among them, 27 (19.0%) carried blaOXA-72, including 22 of 38 isolates from Southern Taiwan (57.9%) and 5 of 62 isolates from Central Taiwan (8.1%). The number of isolates with blaOXA-72 was significantly higher in those obtained from the southern area than those from other areas (57.9% vs. 4.8%, respectively; P < 0.001 by χ2 test). All of the A. baumannii isolates carrying blaOXA-72 were resistant to carbapenems (Table 1). In addition, they were all multidrug resistant [22], but were susceptible to colistin.

Table 1.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antimicrobial agents for Acinetobacter baumannii carrying blaOXA-72

|

Antimicrobial agents |

Isolates carrying blaOXA-72 (n = 27) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50 (mg/L) | MIC90 (mg/L) | Resistance rate (%) | |

| Imipenem |

128 |

128 |

100.0% |

| Meropenem |

>128 |

>128 |

100.0% |

| Ticarcillin |

>128 |

>128 |

100.0% |

| Piperacillin |

>128 |

>128 |

100.0% |

| Ceftazidime |

>128 |

>128 |

100.0% |

| Cefepime |

64 |

>128 |

96.3% |

| Sulbactam |

32 |

32 |

63.0% |

| Ciprofloxacin |

128 |

>128 |

100.0% |

| Colistin | 1 | 1 | 0.0% |

Identifying Ambler class B metallo-β-lactamases and class D β-lactamases

All isolates with blaOXA-72 had the blaOXA-51-like. The blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-58-like, blaOXA-143,blaIMP-like, blaVIM-like, blaGIM-1, blaSPM-1 and blaSIM-1 genes were not detected by PCR methods. In addition, ISAba1 was not detected in any of the strains.

Determination of clonality by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

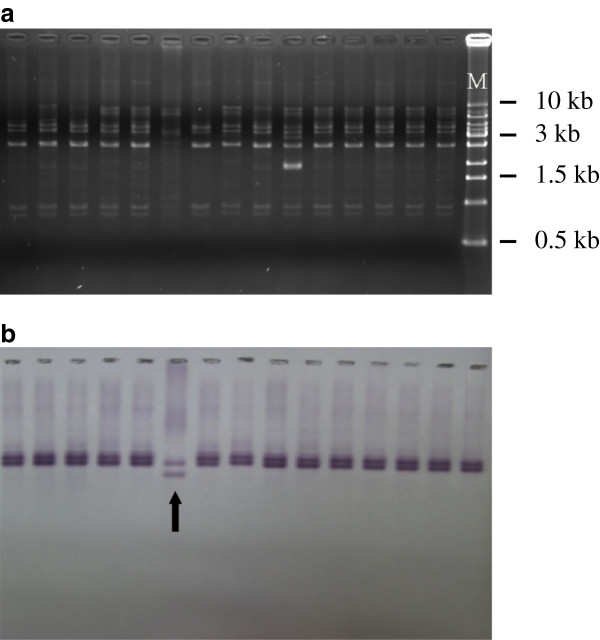

To determine whether emergence of these isolates with blaOXA-72 was due to clonal spread, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis was performed (Figure 1). Twenty-one isolates (77.8% belonged to 2 major clones (A1 and A2) (Figure 1). The other six isolates carrying blaOXA-72 (including isolate 1765) did not belong to the two major clones and had only 65-75% homology related to the major clones. The A1 clone comprised all (5/5, 100%) of the isolates from Central Taiwan and 5 isolates (5/10, 50.0%) from S3 hospital, whereas the A2 clone comprised 10 isolates (10/12, 83.3%) from S2 and 1 isolate (1/10, 10%) from S3 hospital.

Figure 1.

Molecular characteristics of Acinetobacter baumannii carrying blaOXA-72 in Taiwan. The results of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis are shown, followed by the hospitals of the isolates, pulsotype, presence of ISAba1 upstream of blaOXA-51, localization of blaOXA-72, flanking regions of blaOXA-72 (delineated in Figure 3), and results of PCR using primers previously described.

Determination of the plasmid localization of blaOXA-72 by Southern blot

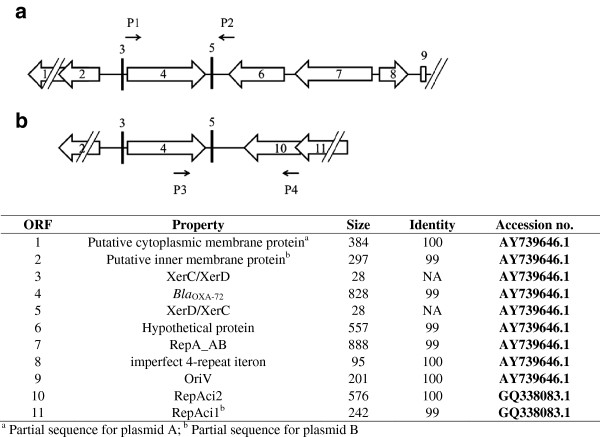

Electrophoresis showed minor differences in plasmid patterns among isolates (Figure 2). Southern blot using a blaOXA-72 probe further revealed the presence of blaOXA-72 in the plasmids obtained from 27 isolates. However, Southern blot also detected two types of segments flanking blaOXA-72 after EcoRI digestion. One was present in isolate 1765 and the other was present in the remaining 26 isolates.

Figure 2.

Electrophoresis (a) and Southern blot (b) of isolates carrying blaOXA-72. The pattern of plasmid electrophoresis and Southern blot was very similar among isolates. However, Southern blot revealed blaOXA-72 in isolate 1765 (arrow) may be located in a different genetic background. All isolates were tested but only the results of 15 isolates (from Lane 1 to 15) were presented. M, marker (Bio-1KBTM Mass DNA Ladder, Protech Technology Enterprise Co., Ltd, Taiwan).

Sequencing of the flanking region of plasmid-borne blaOXA-72 by inverse PCR

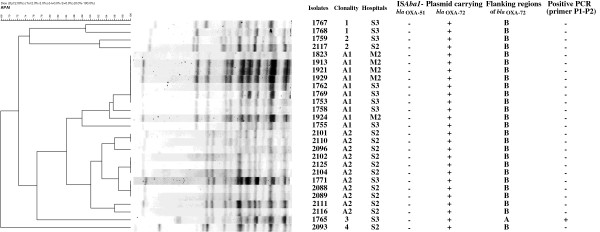

Based on the Southern blot results, we anticipated that there were at least two genetic structures flanking the blaOXA-72 gene. Inverse PCR of isolate 1765 and randomly selected isolates revealed two types of genetic structures flanking the gene (Figures 3a and 3b, fragment A of 3596 bp and B of 2325 bp). An identical 967 bp region containing blaOXA-72 in both fragment A and B was flanked by XerC/XerD and XerD/XerC. The 3596 bp fragment A had 99% similarity to pAB02 (GenBank accession no. AY228470.1) and contained a region with 100% similarity to the plasmids reported from the same teaching hospital (828 bp, accession no. AY739646.1) [13]. In fragment B, the 1195 bp region upstream of XerD/XerC had 99% similarity to that in fragment A, but the region downstream of XerD/XerC was similar to other plasmids without blaOXA-72 (accession no. GQ338083.1), indicating possible recombination between the plasmids. Using a specific primer pair (P3 and P4, Additional File 2) for fragment B (Figure 3), the PCR result was positive in 26 isolates, except isolate 1765. The specific primers used to confirm the presence of fragment A were similar to those used in a previous study (primers P1 and P2, respectively; Figure 3) [13]. Only one isolate (isolate 1765) was positive for fragment A. The mutual exclusion of fragment A and B indicated that they were located on different plasmids, designated as plasmid A and B, respectively.

Figure 3.

Schematic map of the partial flanking region of blaOXA-72 in two types of plasmids (plasmid A and B, Figures3a and3b, respectively) in Taiwan. The arrows indicate the predicted open reading frames (ORFs) and their transcriptional directions. The names of various features are indicated below the map. The sequenced fragment in plasmid A shared 99% similarity to the previously prevalent plasmid (accession no. AY739646.1), whereas the region downstream of XerD/XerC in plasmid B was identical to another plasmid (accession no. GQ338083.1). P1 and P2 primers are specific for plasmid A and P3 and P4 primers are specific for plasmid B.

Determination of the contribution of blaOXA-72 to carbapenem MIC

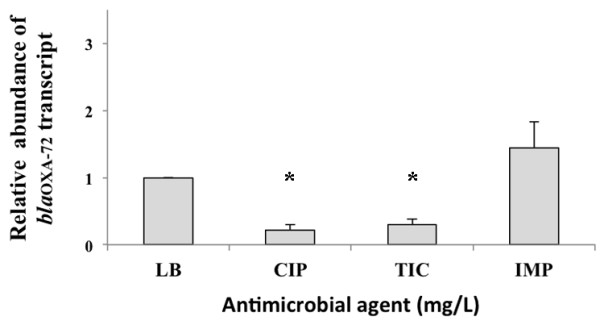

To determine the contribution of blaOXA-72, A. baumannii strain Ab290 was transformed with pYMAb2 and pYMAb2::blaOXA-72, respectively. Compared to Ab290 (pYMAb2), transformation with blaOXA-72 resulted in an increase in the MICs of imipenem, meropenem, ticarcillin, sulbactam, and ampicillin (Table 2). We were interested in determining if the addition of carbapenems would increase OXA-72 expression. Thus, strain Ab290 (pYMAb2::blaOXA-72) was treated with ciprofloxacin, imipenem, and ticarcillin. Quantitative PCR showed that the RNA expression of the gene increased by 8-fold after addition of imipenem compared to addition of ciprofloxacin or ticarcillin (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (mg/L) of antimicrobial agents for Acinetobacter baumannii with or without plasmids carrying blaOXA-72

| Isolates | Imipenem | Meropenem | Ticarcillin | Ampicillin | Sulbactam | Cefepime | Ceftazidime | Ciprofloxacin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ab290 |

0.25 |

0.5 |

8 |

128 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0.5 |

| Ab290 (pAbYM2) |

0.25 |

0.5 |

8 |

128 |

4 |

2 |

4 |

0.25 |

| Ab290 (pAbYM2::blaOXA-72 ) | 32 | 32 | >1024 | >1024 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 |

Figure 4.

Results of quantitative PCR of mRNA levels of OXA-72 in Acinetobacter baumannii carrying blaOXA-72 in response to different antibiotics. The A. baumannii isolate carrying blaOXA-72 was treated without antibiotics (Luria-Bertani broth, LB), or with ciprofloxacin (CIP) at 0.25 mg/L, ticarcillin (TIC) at 1024 mg/L, and imipenem (IMP) at 8 mg/L for 7 hours. Quantitative PCR revealed higher mRNA levels of OXA-72 in isolates treated with imipenem compared to those treated with ciprofloxacin or ticarcillin. * P value < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and by the Scheffe post-hoc method.

Discussion

The resistance rate to carbapenems in A. baumannii has been increasing worldwide. Ambler class D β-lactamases are responsible for the main mechanism of resistance in A. baumannii. BlaOXA-72, which was first discovered in Thailand, has since spread rapidly to other areas of Asia and Europe [9-13]. In this study we collected 142 IRAB from different geographical regions of Taiwan. Among them, 27 IRAB carrying blaOXA-72 gene had successfully spread throughout Southern Taiwan and extended into Central Taiwan. One new type of plasmid, which harbored a different genetic structure compared to that previously reported, not only existed in the two major clones, but also disseminated to other clones. We also found evidence that blaOXA-72 contributed to carbapenem resistance. The mRNA levels of OXA-72 increased in response to the addition of imipenem.

Many studies have demonstrated an association of carbapenem resistance and the presence of blaOXA-72. One study [23] revealed that the plasmid carrying blaOXA-72 modestly increased the MICs of imipenem and meropenem in Escherichia coli (0.125 to 0.25 and 0.016 to 0.032, respectively). Another study [9] showed that transformation of susceptible strains with the entire plasmid carrying blaOXA-72 extracted from clinical isolates resulted in resistance to carbapenems, but not cephalosporins. However, the increase of carbapenem MIC might be attributed to other genetic determinants also present in the transformed plasmid in that study. In our study, we only cloned the blaOXA-72 gene into the plasmid without other resistance mechanisms against carbapenems. The transformation greatly increased the MICs of carbapenems (64-128–fold), which was further supported by the elevated mRNA levels of OXA-72 in response to the addition of imipenem. Moreover, our study has revealed for the first time that the transformation also increased the MICs of ticarcillin, ampicillin, and sulbactam.

The molecular epidemiology of Ambler class D β-lactamases differs among geographical regions [7]. Our previous study showed prevalence of blaOXA-23 in Central Taiwan [24], whereas the current study showed the blaOXA-72 was mainly disseminated in Southern Taiwan. Our study revealed that the clonal spread and plasmid dissemination were important for blaOXA-72, similar to previous studies [13,23,25]. The mechanisms of spread of different carbapenemase genes seemed to be different, as our previous study showed that a transposon may be the main reason of spread of blaOXA-23 in Central Taiwan [24].

Lu et al. found that the plasmid carrying blaOXA-72 was positive for PCR in half of the isolates (49.2%, 29/59) in one teaching hospital in Southern Taiwan using P1 and P2 primers [13]. Our study recovering isolates from multiple centers only identified one isolate from the same hospital assessed in a previous study [13] that may harbor the same plasmid (plasmid A). This suggests that plasmid A may have been replaced by plasmid B during this period. Plasmid B shared part of the genetic structure with plasmid A. The shared regions included not only regions between XerC/XerD binding sites, which were presumed to be responsible for mobilization of blaOXA-72[23,25,26], but also regions upstream from it. This may suggest that these plasmids have undergone a recombination event.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study has revealed that the dissemination of IRAB isolates carrying the blaOXA-72 gene may be due to clonal spread and dissemination of a new plasmid. The blaOXA-72 gene contributed to carbapenem resistance.

Abbreviations

CLSI: Clinical and laboratory standards institute; MIC: Minimal inhibitory concentration; IRAB: Imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SCK and SPY conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and drafted the manuscript. YTL and HCC participated in the sequence alignment, and drafted the manuscript. CPC and CLC carried out the laboratory assays. PLL and PRH collected the clinical isolates. TLC and CPF designed and supervised the study, participated in data analysis and interpretation, and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Distribution of Acinetobacter baumannii carrying bla OXA-72 among 291 A. baumannii isolates collected from 10 teaching hospitals in Taiwan (N, northern; C, central; S southern).

Primers used in this study.

Contributor Information

Shu-Chen Kuo, Email: ludwigvantw@gmail.com.

Su-Pen Yang, Email: spyang@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Yi-Tzu Lee, Email: s851009@yahoo.com.tw.

Han-Chuan Chuang, Email: hanchuan@tzuchi.com.tw.

Chien-Pei Chen, Email: sw5351.chen@msa.hinet.net.

Chi-Ling Chang, Email: alice730109@gmail.com.

Te-Li Chen, Email: tecklayyy@gmail.com.

Po-Liang Lu, Email: d830166@cc.kmu.edu.tw.

Po-Ren Hsueh, Email: hsporen@ntu.edu.tw.

Chang-Phone Fung, Email: cpfung@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Health Research Institute and the National Science Council (98-2314-B-010-010-MY3).

References

- Neonakis IK, Spandidos DA, Petinaki E. Confronting multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a review. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken M, DeCorby M, Fuller J, Loo V, Hoban DJ, Zhanel GG, Mulvey MR. Identification of multidrug- and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Canada: results from CANWARD 2007. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:552–555. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon KT, Oh WS, Song JH, Chang HH, Jung SI, Kim SW, Ryu SY, Heo ST, Jung DS, Rhee JY, Shin SY, Ko KS, Peck KR, Lee NY. Impact of imipenem resistance on mortality in patients with Acinetobacter bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:525–530. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karageorgopoulos DE, Falagas ME. Current control and treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:751–762. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Nordmann P. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms and epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:826–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YT, Kuo SC, Chiang MC, Yang SP, Chen CP, Chen TL, Fung CP. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant non-baumannii species of Acinetobacter harboring a blaOXA-51-like gene that is intrinsic to A. baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1124–1127. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00622-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P. Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:24–38. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01512-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werneck JS, Picao RC, Carvalhaes CG, Cardoso JP, Gales AC. OXA-72-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in Brazil: a case report. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:452–454. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnaud G, Zihoune N, Ricard JD, Hippeaux MC, Eveillard M, Dreyfuss D, Branger C. Two sequential outbreaks caused by multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates producing OXA-58 or OXA-72 oxacillinase in an intensive care unit in France. J Hosp Infect. 2010;76:358–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Kim MN, Choi TY, Cho SE, Lee S, Whang DH, Yong D, Chong Y, Woodford N, Livermore DM. Wide dissemination of OXA-type carbapenemases in clinical Acinetobacter spp. isolates from South Korea. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33:520–524. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Popolo A, Giannouli M, Triassi M, Brisse S, Zarrilli R. Molecular epidemiological investigation of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains in four Mediterranean countries with a multilocus sequence typing scheme. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:197–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PL, Doumith M, Livermore DM, Chen TP, Woodford N. Diversity of carbapenem resistance mechanisms in Acinetobacter baumannii from a Taiwan hospital: spread of plasmid-borne OXA-72 carbapenemase. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:641–647. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TL, Siu LK, Wu RC, Shaio MF, Huang LY, Fung CP, Lee CM, Cho WL. Comparison of one-tube multiplex PCR, automated ribotyping and intergenic spacer (ITS) sequencing for rapid identification of Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:801–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility testing; Twenty-First Information Supplement. Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2011. (CLSI document M100-S21). [Google Scholar]

- Turton JF, Ward ME, Woodford N, Kaufmann ME, Pike R, Livermore DM, Pitt TL. The role of ISAba1 in expression of OXA carbapenemase genes in Acinetobacter baumannii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;258:72–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington MJ, Kistler J, Livermore DM, Woodford N. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding acquired metallo-beta-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:321–322. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LY, Chen TL, Lu PL, Tsai CA, Cho WL, Chang FY, Fung CP, Siu LK. Dissemination of multidrug-resistant, class 1 integron-carrying Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in Taiwan. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:1010–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TL, Wu RCC, Shaio MF, Fung CP, Cho WL. Acquisition of a plasmid-borne blaOXA-58 gene with an upstream IS1008 insertion conferring a high level of carbapenem resistance to Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2573–2580. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00393-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo SC, Fung CP, Lee YT, Chen CP, Chen TL. Bacteremia due to Acinetobacter genomic species 10. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:586–590. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01857-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TL, Chang WC, Kuo SC, Lee YT, Chen CP, Siu LK, Cho WL, Fung CP. Contribution of a plasmid-borne blaOXA-58 gene with its hybrid promoter provided by IS1006 and an ISAba3-like element to beta-lactam resistance in Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3107–3112. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00128-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian GB, Adams-Haduch JM, Bogdanovich T, Pasculle AW, Quinn JP, Wang HN, Doi Y. Identification of diverse OXA-40 group carbapenemases, including a novel variant, OXA-160, from Acinetobacter baumannii in Pennsylvania. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:429–432. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01155-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Chen TL, Lee YT, Huang L, Kuo SC, Yu KW, Hsueh PR, Dou HY, Su IJ, Fung CP. Dissemination of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii carrying blaOXA-23 from hospitals in central Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012. Sep 22 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- D'Andrea MM, Giani T, D'Arezzo S, Capone A, Petrosillo N, Visca P, Luzzaro F, Rossolini GM. Characterization of pABVA01, a plasmid encoding the OXA-24 carbapenemase from Italian isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3528–3533. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00178-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino M, Acosta J, Poza M, Sanz F, Beceiro A, Chaves F, Bou G. OXA-24 carbapenemase gene flanked by XerC/XerD-like recombination sites in different plasmids from different Acinetobacter species isolated during a nosocomial outbreak. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:2724–2727. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01674-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Distribution of Acinetobacter baumannii carrying bla OXA-72 among 291 A. baumannii isolates collected from 10 teaching hospitals in Taiwan (N, northern; C, central; S southern).

Primers used in this study.