Abstract

Introduction

Recent evidence demonstrates increasing rates of violence involvement among adolescent girls. The objective of this study was to describe the types and sources of violence experienced within social contexts of adolescent girls at high risk for pregnancy.

Method

Qualitative data for this analysis are drawn from intervention summary reports of 116 girls participating in Prime Time, a youth development intervention for adolescent girls. Descriptive content analysis techniques were used to identify types and sources of violence experienced by girls within their daily contexts.

Results

Types of violence included physical fighting, witnessing violence, physical abuse, gang-related violence, verbal fighting, verbal abuse and sexual abuse. Sources of violence included family, peers and friends, romantic partners, community violence, and self-perpetrated. Many girls in this study experienced violence in multiple contexts.

Discussion

It is imperative that efforts to assess and prevent violence among adolescent girls pay attention to the social contexts in which these adolescents live.

Keywords: adolescent girls, violence, social context

Introduction

Violence involvement among adolescent girls is a significant public health issue. Recent evidence demonstrates increasing rates of violence among adolescent girls (Chesney-Lind, 2011; Puzzanchera, Stahl, Finnegan, Tiernery & Snyder, 2003; Moretti, Catchpole & Odgers, 2005). National data from the 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Survey indicate that among 9-12th grade girls, 22.9% had been in a physical fight and 21.2% had been bullied on school property within the past 12 months (CDC, 2008). To date, few studies have examined risk factors associated with violence among girls (Adamshick, 2010). Relatively little is known about contexts that contribute to girls’ involvement in violence (Moretti et al., 2005).

In addition to increasing risk for physical injury and emotional harm, violence involvement is known to cluster with other problem behaviors (USDHHS, 2001). Involvement in physical violence increases adolescent girls’ likelihood of engaging with aggressive peer groups, having antisocial romantic partners, becoming pregnant and giving birth as a teen, and engaging in aggressive parenting practices (Kirby, 2007; Pepler at al., 2004). Furthermore, patterns of violence involvement during adolescence have important implications for violent behavior during adulthood. Specifically, adolescents who are exposed to high levels of violence are at increased risk of developing trajectories of violence that persist into their adult years. Among serious adolescent violent offenders, up to 70% of girls continue to engage in aggressive and violent behaviors in adulthood (USDHHS, 2001).

Among mixed-gender groups of adolescents, risk factors for violence occur within family, peer, and community contexts. Within families, child maltreatment, harsh and inconsistent disciplinary practices, physical punishment, parental aggression, and high levels of family conflict and violence have all been linked to aggressive and violent behaviors during adolescence (DiClemente et al., 2001; Herrenkohl et al., 2000). Within peer contexts, adolescents whose friends engage in substance use, violent and criminal behaviors are more likely to be involved in violence (Hawkins et al., 1998; Lipsey & Derzon, 1998). At a community level, adolescents who live in neighborhoods and communities characterized by high levels of social disorganization, poverty, crime and gang activity, scarcity of economic opportunities, and low levels of citizen engagement are at increased risk for involvement in violence (Hawkins et al., 1998; Kramer, 2000; Kroneman, Loeber, & Hipwell, 2004; Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002; Valois, MacDonald, Fischer, & Drane, 2002; Yonas, O’Campo, Burke, & Gielen, 2007).

As noted previously, few studies have specifically examined factors that increase girls’ risk for violence involvement. Known risk factors for violent behaviors among girls include history of violence victimization, experiences of physical and sexual abuse, mental health problems, family disruption, and high levels of neighborhood disorganization (Moretti et al., 2005; Odgers & Moretti, 2002; Molnar, Browne, Cerda & Buka, 2005; Burman, 2003). Findings from Adamshick’s (2010) qualitative study examining the experience of girl-to-girl aggression suggest that for marginalized girls, involvement in violence provides self-protection, expresses identity, and offers a means for finding attachment, connection and friendship.

Although the link between violence involvement and negative health outcomes is well established, less is known about the social contexts of adolescent girls that either encourage or discourage violent behaviors. The purpose of this qualitative descriptive study is to identify the types and sources of violence experienced within social contexts of adolescent girls at high risk for negative health and social outcomes. A clear understanding of the social contexts associated with violent behaviors among high risk adolescent girls can be used to design relevant clinic services and interventions.

Methods

Overview of Prime Time Intervention Study

Qualitative data about types and sources of violence for this paper were drawn from intervention summary reports of girls participating in a randomized controlled trial of Prime Time, a youth development intervention to reduce multiple risk behaviors including violence involvement, sexual risk taking, and school disconnection among high risk adolescent girls. Designed for use by clinics, the Prime Time intervention included a combination of one-on-one case management and peer leadership programming over an 18-month period. During the 18-month intervention, case managers met regularly with individual participants and established consistent, trusting relationships in which they and the teen could address risk and protective factors targeted by the intervention. Case management visits focused on a core set of topics including emotional and social skills and positive family, school and community involvement. Case managers’ practice followed mandated reporting laws.

Evaluation of Prime Time utilized multiple data collection strategies including quantitative survey data from participants and qualitative intervention summary reports from intervention staff. Research design, inclusion criteria, intervention and evaluation methods, and outcomes from the Prime Time randomized controlled trial are described elsewhere (Tanner, Secor-Turner, Garwick, Sieving, & Rush, 2010; Sieving et al., 2011a; Sieving et al., 2011b; Shlafer, McMorris, Sieving, & Gower, in press). All study procedures were approved by university and participating clinics’ institutional review boards.

Sample

The sample for the current study consists of intervention condition participants for whom a qualitative intervention summary report - including entries at 6, 12, and 18 months following study enrollment – was available. Thus, this study’s sample included 116 girls (92% of all intervention condition participants). Intervention summaries were not available for ten intervention participants who did not engage in intervention activities.

Baseline characteristics of the sample for the current study are in Table 1. Similar to the full Prime Time study sample, this subsample had a mean age of 15.7 years at study enrollment. The sample was racially and ethnically diverse, including girls who reported being African American, American Indian, Asian, Euro-American, Latina and from multiple racial/ethnic backgrounds. Girls’ self-reports indicated relatively high levels of social risk: less than half (39%) were living in two-parent homes, 41% moved households one or more times in the past six months, and 42% had immediate family members receiving public assistance. While 96% of the sample were enrolled in school at study baseline, over one-third (37%) had a history of school suspension. Participants’ baseline self-reports suggest high levels of involvement in physical fighting and violence compared to national and statewide samples of girls of similar ages (CDC, 2008; Minnesota Department of Health, 2013). For example, while 14.7% of 9th and 12th grade girls in Minnesota reported hitting or beating someone up in the past 12 months, 42% of girls in this sample noted hitting or beating someone up in a shorter time interval of the past 6 months (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample baseline characteristics (N=116)

| Characteristic | Mean or % |

|---|---|

| Age (range 13-17 years) | 15.7 years |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| American Indian/Native American | 3% |

| Asian/Asian American | 11% |

| Black/African/African American | 47% |

| Hispanic/Latina | 16% |

| White/Euro American | 5% |

| Mixed/Multiple | 18% |

| # Adults/guardians in homea | |

| No adult guardian | 4% |

| 1 adult guardian | 45% |

| 2 adult guardians | 39% |

| Other arrangements | 12% |

| # Places lived, past 6 months | |

| 1 place | 59% |

| 2 places | 25% |

| 3 or more places | 16% |

| Receipt of public assistance, past yearb | |

| No | 33% |

| Yes | 42% |

| Unsure | 25% |

| Currently enrolled in school | 96% |

| Ever suspended from school (%Yes) | 37% |

| Hit or beat someone up in past 6 months | |

| Never | 58% |

| Once or twice | 33% |

| 3 to 5 times | 7% |

| 6 or more times | 2% |

| Used or threatened to use a weapon in past 6 months | |

| Never | 87% |

| Once or twice | 7% |

| 3 to 5 times | 1% |

| 6 or more times | 5% |

Adults/guardians included biological or adoptive mother, biological or adoptive father, stepmother, stepfather, foster mother, foster father, grandmother, grandfather, other guardian

Public assistance includes welfare payments, M-FIP, public assistance, or food stamps

Procedure and Instrument

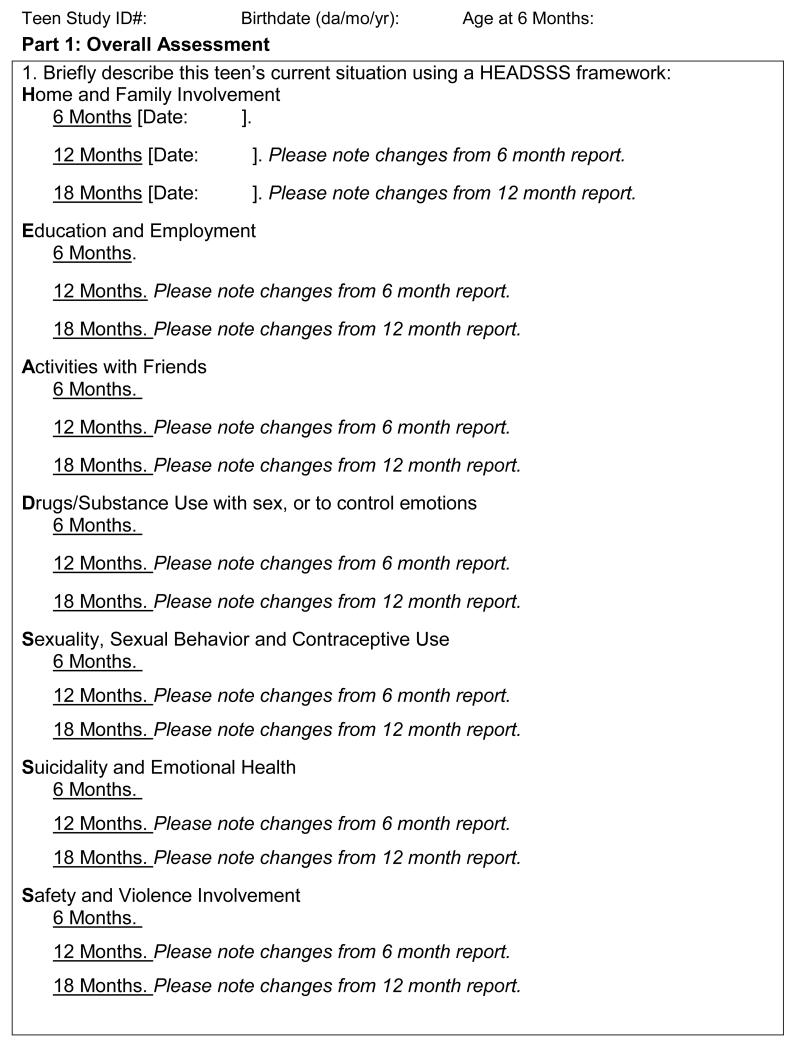

Case managers were trained to systematically complete a qualitative intervention summary report for every participant after 6 months of intervention involvement and to update this summary at a girl’s 12- and 18-month intervention points. This intervention summary used a structured assessment pneumonic (HEADSSS; Goldenring & Rosen, 2004) to frame the case managers’ assessment of risk and protective factors in psychosocial domains including Home and Family Involvement, Education and Employment, Activities with Friends, Drugs/Substance Use, Sexuality, Sexual Behavior and Contraceptive Use, Suicidality and Emotional Health, and Safety and Violence Involvement. With individual participants, case managers were instructed to assess each psychosocial domain and describe changes observed in that domain over the previous 6 months. Intervention summary reports were audited by supervisory staff for completeness. Figure 1 depicts a Prime Time intervention summary report. For this qualitative study, narrative descriptions about experiences of violence were primarily found in the Home and Family Involvement, Education and Employment, and Safety and Violence Involvement sections of intervention summary reports. However, references to violence found in other sections were also included in this analysis.

Figure 1.

Prime Time Intervention Summary

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive content analysis techniques were used to identify the range of types (or forms) and sources (or places) of violence experienced within the social contexts of adolescent girls at high risk for early pregnancy. After reading each intervention summary report in its entirety, the first author used open coding strategies to identify and categorize the types and sources of violence found within intervention summaries. Based on this preliminary analysis within cases she compiled a codebook of categories organized by types and sources of violence utilizing Crabtree and Miller’s (1999) template approach to coding. This codebook was used by two raters to independently and systematically code each unique episode of violence first by type and then by the source of violence as described in the intervention summaries.

Trustworthiness of the data was established by maintaining an audit trail and by having more than one rater code the data. A third research team member with extensive qualitative research experience reviewed and used the coding scheme to resolve a couple of disagreements between coders by clarifying the operational definition of the gang violence coding category.

Results

Descriptions of one or more unique episodes of violence were found in 69 of this study’s 116 intervention summary reports. Examples of each type of violence recorded by case managers within individual participants’ intervention summaries are included in Table 2. As seen in Table 2, violence episodes were categorized into seven types of violence. Types of violence included both physical and relational forms of violence and included experiences of violence as perpetrator or victim. The most prevalent type of violence was physical fighting, recorded in 33 cases. The second most prevalent type was witnessing violence such as domestic abuse or neighborhood violence, which was recorded in 27 cases. A total of 22 cases of physical abuse were noted including physical abuse or punishment by a parent or caregiver. Gang-related violence such as witnessing gang-related fighting or gun violence was noted in 17 cases. Verbal fighting, including arguing and yelling, was reported in 10 cases. Verbal abuse and sexual abuse were the least prevalent types of violence reported in intervention summaries from these participants, with each being recorded in 6 cases.

Table 2.

Types of violence involvement by case.

| Type of Violence | Intervention Summary Exemplar | Number of Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Physical fighting | “Continues to fight at school. ” | 33 |

| “Reports fighting with friends. ” | ||

| “Kicked out of high school for fighting. ” | ||

| “Gets in lots of fights with friends and physical fights with mom and boyfriend. ” |

||

| Witnessing violence (e.g., domestic abuse) | “ Domestic violence involving mother. ” | 27 |

|

“

Reports witnessing shootings at people she

was with. ” |

||

| Physical abuse | “ Mother uses beatings as punishment. ” | 22 |

| “Recently assaulted by ex-boyfriend. ” | ||

|

“

Physical abuse by mother and brother

because she is dating a gang member. ” |

||

| Gang-related violence | “Involved in gang violence. ” | 17 |

| “Teen and friends involved in gang. ” | ||

|

“

Gang violence in home due to brother’s

involvement. ” |

||

| Verbal fighting/arguing | “Teen reports lots of fighting with her sister over an ex-boyfriend.” |

10 |

| “Repeatedly runs away from foster home due to fighting with foster mom. ” |

||

| “Verbal fighting with mom. ” | ||

| Verbal abuse |

“

Verbal and emotional abuse from mom’s

boyfriend. ” |

6 |

|

“

Involved in verbally abusive relationship

with older man. ” |

||

| “Verbal abuse from brother at home. ” | ||

| Sexual abuse | “History of sexual abuse by uncle. ” “History of rape from her best friend. ” |

6 |

|

“

Sexually abused as a child, now prostituting

for housing. ” |

In terms of sources of violence, the most common place that violence was documented was at home within families. A total of 50 cases of violence within families were noted (Table 3). The second most common source of violence was peers and friends. This source included peers and friends at school, in the community, and in other social settings such as organized recreation or sports activities. Violence from romantic partners was the source of violence in 18 cases. Participants also reported community violence, including physical fighting and gang-related violence as previously described. Self-perpetrated violence, namely cutting, was least prevalent among this sample and recorded in only 3 cases.

Table 3.

Sources of violence involvement by case.

| Source of Violence | Intervention Summary Exemplar | Number of Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Family | “ Domestic violence involving mother. ” | 50 |

| Peers/Friends | “Reports fighting with friends. ” | 31 |

| Romantic Partner | “Recently assaulted by ex-boyfriend. ” | 18 |

| Community |

“

Exposure to lots of violence in housing

complex. ” |

10 |

| Self-perpetrated | “History of cutting behavior. ” | 3 |

To assess participants’ aggregate experiences with violence, we coded the number of sources and types of violence for each participant for whom violence was described in her intervention summary. As depicted in Table 4, more than half (n=69/116; 59.5%) of study participants were noted to experience one or more types of violence. Case managers documented two or more types of violence in the lives of nearly one-third (n=35/116; 30.2%) of participants. For example, one participant’s intervention summary indicated the teen was engaged in fighting with peers at school (physical fighting), witnessing domestic violence in her home (witnessing violence), and living in a neighborhood in which drive-by shootings regularly occurred (gang-related violence). Over one-quarter (n=33/116; 28.5%) of girls had two or more sources of violence in their daily lives. For instance, the participant described in the previous example experienced violence among friends and peers, within her family, and in her community.

Table 4.

Aggregate experiences of violence.

| Types of Violence | Total # of Cases | Cumulative % of Total Sample (N=116) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 type | 34 | 29.3% |

| 2 types | 18 | 44.9% |

| 3 types | 15 | 57.8% |

| 4 or more types | 2 | 59.5% |

| Sources of Violence | ||

| 1 source | 36 | 31% |

| 2 sources | 20 | 48.2% |

| 3 sources | 11 | 57.7% |

| 4 or more sources | 2 | 59.5% |

Discussion

Aggressive and violent behaviors were prevalent among this sample of high-risk adolescent girls, as evidenced by their baseline self-reports. Indeed, girls’ violent behaviors may have been a reflection of the violence in their daily lives. Intervention summary reports indicate that violence was a pervasive aspect of these girls’ social contexts. More than half (59.5%) of this sample experienced at least one form of violence in their everyday lives; nearly one-third (30.2%) experienced two or more types of violence. Furthermore, participants experienced violence in multiple contexts, including at home, in school, and within their communities. Over half (59.4%) of participants reported violence in at least one of their everyday contexts; over one quarter (28.5%) experienced violence in two or more of their regular social contexts. These adolescents’ families as well as their peers and friends were the most common sources of violence.

Findings from this study highlight known risk factors for girls’ involvement in violence and underscore the complex nature of the link between girls’ violence exposure and involvement. Among girls in this sample, exposure to violence was ubiquitous. Witnessing violence and experiences of physical abuse were among the most common types of violence. Previous research indicates that witnessing violence, physical abuse and other forms of violence victimization are potent risk factors for violence perpetration during adolescence (Borowsky, Widome, & Resnick, 2008; Moretti et al., 2005; Odgers & Moretti, 2002). Previous research also identifies a link between social contexts fostering violence and violent behavior among adolescents. For example, routine exposure to violence within the community and lower quality home environments are well-established risk factors for youth violence (Borowsky et al., 2008). Over 60 cases of violence occurring within family and community contexts suggests that exposure to violence in these environments was commonplace within this sample of 116 adolescent girls. Within this sample, the pervasiveness of such exposures helps to explain the high prevalence of self-reported fighting and violent behaviors.

Given findings from this study and from previous research, it is imperative that efforts to address violence among adolescent girls pay attention to the social contexts in which these adolescents live that may promote violence involvement. Understanding the compounding effects of experiencing multiple forms of violence is important in developing effective violence prevention programs and policies (Krug et al., 2002). Adolescent girls living in contexts where violence is normative at individual, relational and community environmental levels need clear social messages, role models and skills that explicitly support alternatives to violence (Borowsky et al., 2008; Resnick, Ireland, & Borowsky, 2004).

Limitations

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting study findings. First, reports of violence were from the standpoint of the case manager in intervention summaries updated at 6-month intervals over a period of 18 months. Thus findings reflect the types and sources of violence emphasized by the girls in working with their case managers, rather than representing the actual occurrence of specific violence episodes. Second, several forms of violence, including physical and sexual abuse, required mandatory reporting by the case managers. This requirement may have limited girls’ reports of these forms of violence, resulting in underestimation by case managers. Despite these limitations, case managers’ observations (as recorded in intervention summary reports) are an important source of data supplementing girls’ self-reports. These observations provide a systematic assessment of the types and sources of violence experienced by adolescent study participants in their daily social contexts.

Implications for Practice

While additional research is needed to fully understand risk factors and pathways to violence among adolescent girls, findings from this study have important implications for nurses and other health professionals providing direct services to youth. Given striking recent increases in the prevalence of relational aggression and physical violence among girls, routine screening about types and sources of violence in girls’ lives is warranted. Having a complete picture of the ways in which an adolescent girl is experiencing violence is critical for assessing her risk for violence involvement and for developing effective prevention strategies. For girls who note multiple types and sources of violence in their lives as well as for those who describe regular involvement in violent behavior, further intervention is warranted.

The externalizing of relational and physical aggression among adolescent girls may reflect social contexts characterized by multiple types and sources of violence. A 2001 U.S. Surgeon General’s Report on Youth Violence (USDHHS, 2001) called for adoption of evidence-based approaches to preventing youth violence, including programs that employ dual strategies of addressing risks while building protective factors that buffer adolescents from violence involvement. Existing research suggests that programs addressing known risk and protective factors for youth violence at individual and social contextual levels are more effective than programs that address isolated risk behaviors or do not address issues within the larger social context (Flay, Graumlich, Segawa, Burns, & Holliday, 2004; Jagers, Morgan-Lopez, Flay, & Aban Aya Invesigators, 2009). To effectively address pervasive violence that occurs at individual, relational, and community levels requires comprehensive, sustained approaches including effective prevention strategies at each of these levels (Prevention Institute, 2010). For young people from urban neighborhoods characterized by deep poverty, residential mobility and violence, multifaceted, sustained preventive interventions may be particularly important (Flay et al., 2004; Limbos et al, 2007; Jagers et al., 2009).

Acknowledgment

This project was supported with funds from the National Institute of Nursing Research (5R01NR008778; R. Sieving, PI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Molly Secor-Turner, North Dakota State University, Department of Nursing, 2670, PO Box 6050, Fargo, ND 58108, molly.secor-turner@ndsu.edu.

Ann Garwick, University of Minnesota, School of Nursing, 308 Harvard St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414, garwi001@umn.edu.

Renee Sieving, University of Minnesota, School of Nursing, 308 Harvard St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414, sievi001@umn.edu.

Ann Seppelt, University of Minnesota, School of Nursing, 308 Harvard St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414, siec0007@umn.edu.

References

- Adamshick PZ. The lived experience of girl-to-girl aggression in marginalized girls. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20(4):541–555. doi: 10.1177/1049732310361611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky IW, Widome R, Resnick M. Young people and violence. In: Heggenhougen K, Quah S, editors. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Academic Press; San Diego: 2008. pp. 675–684. [Google Scholar]

- Burman M. Challenging conceptions of violence: A view from the girls. Sociology Review. 2003;13(4):2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(SS-4):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney-Lind M. Are girls closing the gender gap in violence? 2011 Retrieved April, 2011, from http://www.abanet.org/crimjust/cjmag/16-1/chesneylind.html.

- Crabtree HF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research: Research Methods for primary care. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingwood G, Crosby R, Sionean C, Cobb BK, Harrington K, Davies S, Hook E, III, Oh M. Parental monitoring: association with adolescents’ risk behaviors. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1363–1368. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Graumlich S, Segawa E, Burns JL, Holliday MY. Effects of 2 prevention programs on high-risk behaviors among African American youth: A randomized trial. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:377–384. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenring JM, Rosen DS. Getting into adolescent heads: An essential update. Contemporary Pediatrics. 2004;21:64–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Herrenkohl T, Farrington DP, Brewer D, Catalano RF, Harachi TW. A review of predictors of youth violence. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 106–146. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl T, Maguin E, Hill K, Hawkins J, Abbott R, Catalano R. Developmental risk factors for youth violence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26:176–186. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ, Morgan-Lopez AA, Flay BR, Aban Aya Investigators The impact of age and type of intervention on youth violent behaviors. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30:642–658. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Emerging Answers 2007: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer RC. Poverty, inequality, and youth violence. Annals of the American Academy of Political & Social Science. 2000;567:123–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kroneman L, Loeber R, Hipwell AE. Is neighborhood context differently related to externalizing problems and delinquency for girls compared with boys? Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review. 2004;7:109–122. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000030288.01347.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World report on violence and health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Limbos MA, Chan LS, Warf C, Schneir A, Iverson E, Shekelle P, Kipke MD. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent youth violence: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Derzon JH. Predictors of violent or serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood: a synthesis of longitudinal research. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Department of Health [Accessed January 21, 2013];Minnesota Student Survey. 2007 http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/chs/mss/statewidetables/

- Molnar BE, Browne A, Cerda M, Buka SL. Violent behavior by girls reporting violent victimization: A prospective study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(8):731–739. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti M, Catchpole RE, Odgers C. The darkside of girlhood: Recent trends, risk factors and trajectories to aggression and violence. The Canadian Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Review. 2005;14(1):21–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Moretti MM. Aggressive and antisocial girls: Research update and challenges. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 2002;1:103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Prevention Institute UNITY Road Map: A Framework for Effectiveness and Sustainability. 2010 Available online at www.preventioninstitute.org/UNITY.html.

- Pepler D, Craig W, Yuile A, Connolly J, Putallaz M, Bierman KL. Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls: A developmental perspective. Guilford Press; New York: 2004. Girls who bully: A developmental and relational perspective; pp. 90–109. [Google Scholar]

- Puzzanchera C, Stahl AI, Finnegan TA, Tierney N, Snyder HN. Juvenile Court Statistics 1998. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD. Protective factors, resiliency, and healthy youth development. Adolescent Medicine: State of the Art Reviews. 2000;11(1):157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Ireland M, Borowsky IW. Youth violence perpetration: What protects? What predicts? Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:424.e1–424.e.10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlafer R, McMorris BJ, Sieving RE, Gower A. The impact of family and peer protective factors on girls’ violence perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.015. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, Resnick M, Garwick A, Bearinger L, Beckman K, Oliphant J, Plowman S, Rush K. A clinic-based, youth development approach to teen pregnancy prevention. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2011a;35:346–358. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.3.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, McMorris BJ, Beckman K, Pettingell SL, Secor-Turner M, Kugler K, Garwick A, Resnick M, Bearinger LH. Prime Time: 12-month sexual health outcomes of a clinic-based intervention to prevent pregnancy risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011b;49(2):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner A, Secor-Turner M, Garwick A, Sieving R, Rush K. Engaging high risk youth in Prime Time: Perspectives of case managers. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2012;26(4):254–265. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Youth violence: A report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Valois RF, MacDonald JM, Fischer MA, Drane JW. Risk factors and behaviors associated with adolescent violence and aggression. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2002;26:454–464. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.6.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonas MA, O’Campo P, Burke JG, Gielen AC. Neighborhood-level factors and youth violence: Giving voice to the perceptions of prominent neighborhood individuals. Health Education and Behavior. 2007;34(4):669–85. doi: 10.1177/1090198106290395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]