Abstract

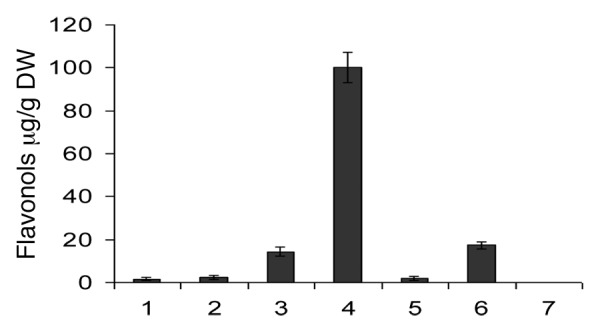

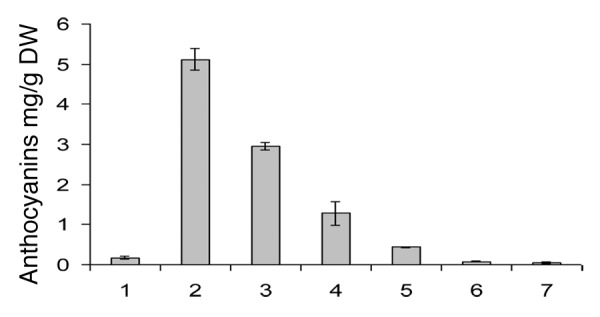

Illicium verum (badiane or star anise), Crataegus oxyacantha ssp monogyna (hawthorn) and Allium cepa (onion), have traditionnally been used as medicinal plants in Algeria. This study showed that the outer layer of onion is rich in flavonols with contents of 103 ± 7.90 µg/g DW (red variety) and 17.3 ± 0.69 µg/gDW (white variety). We also determined flavonols contents of 14.3 ± 0.21 µg/g 1.65 ± 0.61 µg/g for Crataegus oxyacantha ssp monogyna leaves and berries and 2.37 ± 0.10 µg/g for Illicium verum. Quantitative analysis of anthocyanins showed highest content in Crataegus oxyacantha ssp monogyna berries (5.11 ± 0.266 mg/g), while, inner and outer layers of white onion had the lowest contents with 0.045 ± 0.003mg/g and 0.077 ± 0.001 mg/g respectively.

Flavonols extracts presented high antioxidant activity as compared with anthocyanins and standards antioxidants (ascorbic acid and quercetin). Allium cepa and Crataegus oxyacantha ssp monogyna exhibited the most effective antimicrobial activity.

Keywords: flavonoids, flavonols, anthocyanins, antioxydant activity, antibacterial activity

Introduction

Plants produce a wide range of secondary metabolites that exhibit antioxidant activities such as phenolic compounds (phenolic acids, flavonoids, quinines and coumarins), nitrogen compounds (alkaloids and amines), vitamins, terpenoids and others.

Free radicals (FR) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced through physiological and biochemical processes in the human body.1 ROS includes a number of chemically reactive molecules derived from oxygen such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2-), hydroxyl radical (OH-), etc. Overproduction of such free radicals might lead to oxidative damage of biomolecules in the body (e.g., lipids, proteins and DNA), that can initiate diseases such as atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, cancer and heart and neurodegenerative diseases.2

As polyphenols were found to be beneficial as strong antioxidants,3 the evaluation of polyphenols and antioxidant activity has become important to understanding the healing property of medicinal plants that provide opportunities for new drugs.

Among secondary metabolites produced by vegetables, flavonoids constitute an important group of natural polyphenols among which flavonols and anthocyanins are recognized to exhibit a vast range of biological effects.

A number of plants have therapeutic potential, such as Illicium verum (badiane or star anise), Crataegus oxyacantha ssp monogyna (hawthorn) and Allium cepa (onion). I. verum (Schisandraceae) is a little tree that grows in the south of China and north of Viêt-Nam. It is an aromatic plant which produces oils such as anethol and contains some polyphenols, including flavonols (quercetin and kaempferol), anthocyanins, tanins and phenolics acids like shikimic and gallic acid.4 Antimicrobial, antifungal and antioxidant5 activities have been reported for I. verum.

The seeds of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna (Rosaceae) are rich in flavonoids,6 and the plant is considered as a cardiotonic, diuretic and an antispasmodic.7

A. cepa L (Amaryllidaceae), contains many flavonoids, with quercethin as the most abundant flavonol, oils, organosulfuric compounds and saponins. It has been attributed with anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antimicrobial, antispamodic and antioxidant8,9 activities.

The aim of this study was to determine antioxidant and antibacterial effects of aglycones (flavones/flavonols) and anthocyanins extracts from I. verum, C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna and A. cepa.

Results

Total flavonols and anthocyanins content

Quantitative spectrophotometric study of the extracts of I. verum (badiane), C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna (hawthorn) and A. cepa (onion), showed total flavonols contents ranging from 103 µg/g to 1.65 µg/g. Inner layers extract of the red onion had the highest content (103 ± 7.90 µg/g), followed by outer layers of the white onion (17.3 ± 0.69 µg/g) and the leaves of hawthorn (14.3 ± 0.21µg/g). The berry extract of the C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna (hawthorn) (1.65 ± 0.61 µg/g), outer layers of the red onion (2.37 ± 0.10 µg/g) and the inner layers of the white onion (negligible) exhibited the lowest flavonol contents (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Flavonols content in µg/g “quercetin” expressed as (DW). 1, Illicium verum; 2, C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna berries; 3, C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna leaves; 4, inner layers of red onion; 5, outer layers of red onion; 6, inner layers of white onion; 7, outer layers of white onion.

The anthocyanins content varied between 5.11 ± 0.27 and 0.045 ± 0,003 mg/g C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna (hawthorn) berry extract presented the highest content (5.11 ± 0.266 mg/g), followed by hawthorn leaves (2.96 ± 0.9 mg/g) and the outer layer of red onion (1.283 ± 0.569 mg/g). The white onion had the lowest content with 0.045 ± 0.0335 mg/g for the inner layer and 0.077 ± 0.001 mg/g for the outer layer (Fig. 2). The outer layer of white and red onion had the highest proportions in flavonols with 27.76% and 7.73%. The respective proportions in anthocyanins were 72.23% and 92.56%.

Figure 2. Anthocyanins content mg.g−1 “Cyanidin-3-glucoside” (DW). 1, Illicium verum; 2, C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna berries; 3, C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna leaves; 4, inner layers of red onion; 5, outer layers of red onion; 6, inner layers of white onion; 7, outer layers of white onion.

Evaluation of anti-oxidant capacity

The antioxidant activity of plant extracts was expressed as IC50 (half inhibitory concentration). The results were compared with those of quercetin and ascorbic acid. For flavonols lowest IC50 was obtained for the berries of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna (5.67 × 10−7 mg/ml) followed by I.verum (2.89 10−6 × mg/ml), leaves of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna (IC50 = 2.36 × 10−5 mg/ml) and outer layer of red onion (IC50 = 2.91 × 10-5 mg/ml). The comparison with quercitin as antioxidants showed that extract from berries of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna were 1000-fold more efficient, I. verum was 100-fold more efficient and C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna leaves and the external tunic of red onion 10-fold more efficient. The anthocyanin extract of outer and inner layers of white onion showed high free radical scavenging activities with respectively IC50 = 2.69 × 10−5 and 5.89 × 10−5 mg/mL, followed by the I.verum with IC50 = 4.06 × 10−5 mg/mL. The anthocyanins extracts of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna berries and the outer and inner layers of the white onion exhibited a 10-fold higher antioxidant scavenging activity as compared with ascorbic acid. Extracts of leaves and berries of the C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna had a lower activity than ascorbic acid (Table 1).

Table 1. Free radical scavenging activity and reducing power in tested plants on dry weight basis.

| CI50 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (mg.g−1DW) Plants |

1 |

2 |

||

| Star Anis |

2.89 × 10−6 |

4.06 × 10−5 |

||

| Hawthorn |

Berries |

5.67 × 10−7 |

7.66 × 10−4 |

|

| |

Leaves |

2.36 × 10−5 |

3.22 × 10−4 |

|

| Red onion |

Outer layer |

2.91 × 10−5 |

7.53 × 10−4 |

|

| |

Inner layer |

6.06 × 10−3 |

3.52 × 10−4 |

|

| |

Outer layer |

3.21 × 10−4 |

2.69 × 10−5 |

|

| White onion |

Inner layer |

NI |

5.89 × 10−5 |

|

| Quercetin |

1.33 × 10−4 |

|||

| Ascorbic acid | 2.75 × 10−4 | |||

1, flavonols; 2, Anthocyanins

Antibacterial activity

Antibacterial activity of the plant extracts was evaluated in vitro against four bacterial test species known to cause humans infections. Extracts of A. cepa L and C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna were the most effective (Table 2). The largest inhibition zone was observed with flavonols of the inner layer of A. cepa L “Red Onion” (40 mm), inhibiting the Gram-negative Escherichia coli. Flavonols extracts from I. verum and C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna were slightly effective against Escherichia coli with an inhibition zone of 18 mm and 12 mm, respectively. Extracts of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna berries and sheet of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna (flavonols and anthocyanins) were also effective (30 mm), but only inhibited the growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. None of the extracts from C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna and I. verum inhibited S. aureus.

Table 2. Diameters of inhibition zones (mm).

| Bacteria species | Allium cepa “Red Onion” | Allium cepa “White Onion” | Crataegus oxyacantha | Illicium verum | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner layers |

Outer layers |

Inner layers |

Outer layers |

Leaves Berries |

|

|||||||||

| 1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

||

|

Eschericia coli ATCC 25992 |

12 |

- |

- |

- |

40 |

- |

- |

13 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

18 |

- |

|

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27852 |

9 |

- |

12 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

30 |

20 |

25 |

30 |

- |

- |

|

S. aureus ATCC 25923 |

10 |

- |

- |

16 |

- |

- |

- |

11 |

- |

- |

12 |

- |

- |

13 |

|

S. aureus ATCC 43300 |

- | - | 12 | 18 | 13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

1, Flavonols; 2, Anthocyanins; –, no activity.

Discussion

It is generally expected that, when antimicrobial activity is measured, most of the materials tested would be active against Gram-positive bacteria.10-12 In this study, extracts inhibited especially Gram-negative bacteria.

Plants contain a wide range of phenolic compounds, including simple phenolics, phenolic acids, anthocyanins, hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives and flavonoids. All have drawn considerable attention because of their physiological functions including free radical scavenging. Our results showed that white and red onions had the highest contents of aglycones, while the berries and leaves of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna had the highest anthocyanin contents. Red onion contained more aglycones than the white variety and was rich in anthocyanin. Flavonoid content was higher in the outer layer than in the inner layer. This difference could be explained partly by the age of the tissue (the outer layer is older than the inner layer) and partly by the protective role of the outer layer against radiation.13,14

Leaves of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna were richer in flavonoids than the berries as aglycones accumulate in epidermal cells of leaves where they protect the parenchyma against the harmful effects of UVB radiation in the 280–315 nm range.15 Anthocyanins are responsible for the color of flowers and fruits, which explains the richness of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna berries in anthocyanin.16

Our results confirm data from the literature reporting that onion contains more aglycones than hawthorn.14,17,18 Flavonic extracts of the three plants exhibited very high antioxidant properties as compared with standard antioxidants (quercetin and ascorbic acid). But flavonoid contents were not correlated with the anti-reducing power for the different species. Flavonoids seem to be effective donors of hydrogen to DPPH radical, because of their ideal chemical structure. Flavonols (e.g., quercetin), are considered as an antioxidant model due to their ability to scavenge free radicals.19 The extracts showed a higher antioxidant activity than quercetin that could be explained by the presence of other phenolic compounds (phenolic acids, flavanols and flavones), also endowed with a significant antioxidant activity. However, the highest antioxidant activity of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna extracts could be attributed to the presence of epicatechine (flavan-3-ol) which is present in very high amounts as compared with quercetin.18

For I. verum, anti-oxidant activity could be attributed to gallic acid present in higher amount than the other phenolic compounds such as quercetin and kaempherol.20 Flavonols of the outer layer of the red onion had the highest antioxidant activity as compared with the white variety. This result could be linked to its richness in quercetin.14 Overall, aglycones had a higher antioxidant activity as compared with anthocyanins, which could be due to the structure of flavonols. In fact, the ability to scavenge free radicals depends on many structural factors.21 Flavonols are considered powerful compounds, particulary quercetin which contains all criteria previously described (antioxidant and anti-inflammatory). Anthocyanins differ from other flavonols by the absence of the double bond C2-C3 and the function 4-oxo, which could explain their lower antioxidant activity. Therefore, the antioxidant activity depends on the concentration, the structure and the nature of the flavonic compounds.

The antibacterial activity study showed that extracts of A. cepa L and C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna were the most effective. However, flavonols of the inner layer of red onion had a larger inhibiting activity on the growth of Escherichia coli than those of I. verum and C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna. Flavonols and anthocyanins of leaves and berries of C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna were active on the growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Their strong antibacterial activity against Gram-negative bacteria could be explained by the effect of these molecules (flavonols and anthocyanins) on the parietal cells and the cytoplasmic membrane activity. They inhibit the activity of some extracellular and intracellular enzymes such as deshydrogenase important for the bacterial metabolism and the synthesis of compounds essential for their growth. They can also chelate some heavy metal necessary for the enzymatic reactions such as iron.17,22 The outer layers of red onion were slightly effective against Staphylococcus aureus, but none of the extracts obtained from C. oxyacantha ssp monogyna and I. verum had an inhibitory effect against these species. This resistance could be related to the organization and structure of the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria, which have a lipopolysaccharides-rich membrane forming a barrier against the penetration of active molecules, whereas Gram-positive bacteria do not possess such a structure.12

Materials and Methods

Chemicals compound

2,2- diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, (DPPH) ascorbic acid (AA) and quercetin

Plant materials

We used three species considered as healing plants: Allium cepa (onion) with two varieties (red and white), including the inner and the outer layers, Crataegus oxyacantha ssp monogyna (hawthorn), which is encountered in the north of Algeria, and Illicium verum (star anise or badiane), whose used part is the fruit (commercial variety).

Flavonols determination

We used the protocol of Kundan and Anupam23 that relies on acid hydrolysis of glycosides of plant material. The flavonols are extracted by ethyl ether, evaporated and taken up in methanol. A differential spectrophotometric assay allowed the flavonoid estimation at 420 nm in the presence of AlCl3. The amount is expressed as equivalent microgram of quercetin.

Anthocyanins determination

Total anthocyanin contents in the extracts were determined according to Lebreton et al.24 After extraction with methanol (1%) and centrifugation, the absorbance was measured at λ = 530 nm and λ = 657 nm. The formula A = (A530 - 0.25 A657) was used to compensate for absorption of chlorophyll and its degradation products at 530 nm. The anthocyanin content was expressed as milligrams of cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalent per gram.

Evaluation of antioxidant capacity

DPPH radical scavenging activity was followed by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 517 nm that occurs due to the reduction by the antioxidant or reaction with a radical species. DPPH is widely used to test the ability of compounds to act as hydrogen donors or free radical scavengers and to evaluate antioxidant activity of foods. Different levels of methanol extract (10, 25, 50, 100 and 200 μg/ml) were reacted with 2 ml of DPPH solution (0.004% w/v). The mixture was allowed to settle in the dark for 30 min and then absorbance (A) was read at 517 nm, against the blank (methanol) used to take into account the samples color. The radical-scavenging activity was expressed as percentage of inhibition.25 Inhibition (%) = (A control - A sample) X100/A control. EC50 and anti-radical power (ARP) were also estimated and calculated.26,27

Antibacterial activity

We used the well diffusion method (NCCLS, 2002). Four bacterial strains were used: Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27852, Escherichia coli ATCC 25992, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 43300. Strain were cultivated in nutrient broth and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Then, dilution (10−2) was prepared in sterile physiological water for each culture and Muller-Hinton agar (Difco) plates were inoculated and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. Wells, 4 mm in diameter, were cut in the agar and filled with 100 µl of extract solutions. As a control, 100 µL of quercetin and ascorbic acid were poured into a well in the center of each 118- Petri dish. The diameter of the inhibition zone was measured after 24 h of incubation at 119- 37°C and the activity determined as reported,10 by Meena and Sethi10 and Kroyer.27

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the BCM Laboratory and LBPO of the FSB/USTHB. The authors thank also Pierre Roger for his comments on the manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/bioe/article/24435

References

- 1.Ao C, Li A, Elzaawely AA, Xuan TD, Tawata S. Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Ficus microcarpa L., fil extract. Food Contr. 2008;19:940–8. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2007.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun AY, Wang Q, Simonyi A, Sun GY. Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. 2nd ed. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arumugam S, Thandavarayan RA, Arozal W, Sari FR, Giridharan VV, Soetikno V, et al. Quercetin offers cardioprotection against progression of experimental autoimmune myocarditis by suppression of oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress via endothelin-1/MAPK signalling. Free Radic Res. 2012;46:154–63. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.647010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang GW, Hu WT, Huang BK, Qin LP. Illicium verum: a review on its botany, traditional use, chemistry and pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chouksey D, Sharma P, Pawar RS. Biological activities and chemical constituents of Illicium verum hook fruits (Chinese star anise) Der Pharmacia Sinica. 2010;1:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prakash D, Singh BN, Upadhyay G. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of phenols from onion (Allium cepa) Food Chem. 2007;102:1389–93. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.06.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma SK, Jain V, Verma D, Khamesra R. Crataegus oxyacantha- A Cardioprotective Herb. J Herb Med Toxicol. 2007;1:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aguirre L, Arias N, Macarulla MT, Gracia A, Portillo MP. Beneficial Effects of Quercetin on 241 Obesity and Diabetes. J Nutraceuticals. 2011;4:189–98. doi: 10.2174/1876396001104010189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulzomi P, Galluzzo P, Bolli A, Leone S, Acconcia F, Marino M. The pro-apoptotic effect of quercetin in cancer cell lines requires ERβ-dependent signals. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:1891–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meena MR, Sethi V. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils from spices. Jour Food Sci Technol. 1994;31:68–70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman M, Henika PR, Mandrell RE. Bactericidal activities of plant essential oils and some of their isolated constituents against Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella enterica. J Food Prot. 2002;65:1545–60. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-65.10.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shan B, Cai YZ, Brooks JD, Corke H. The in vitro antibacterial activity of dietary spice and medicinal herb extracts. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;117:112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCutcheon AR, Ellis SM, Hancock RE, Towers GH. Antibiotic screening of medicinal plants of the British Columbian native peoples. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992;37:213–23. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90036-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ela F, Kara S, Varani G. Structure of HIV-1TAR RNA in the absence of ligands reveals a novel configuration of the trinucleotide bugle. Nud Acids Res. 1996;24:3974–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.20.3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benkeblia N. Free-Radical Scavenging Capacity and Antioxidant Properties of Some Selected Onions (Allium cepa L.) and Garlic (Allium sativum L.) extracts. Braz Arch of Biol Techn. 2005;48:753–9. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132005000600011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prakash D, Upadhyay G, Pushpangadan P. Antioxidant Potential of Some Under-Utilized 290- Fruits. Indo-Global Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011;1:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Middleton E, Jr., Kandaswami C, Theoharides TC. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:673–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pérez-Gregorio RM, García-Falcón MS, Simal-Gándara J, Rodrigues AS, Almeida DPF. Identification and quantification of flavonoids in traditional cultivars of red and white onions at 288- harvest. J Food Compost Anal. 2010;23:592–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2009.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harborne JB, Williams CA. Advances in flavonoid research since 1992. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:481–504. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruneton J. Pharmacognosie, phytochimie, plantes medicinales. 4th ed. Paris (France); Lavoisier: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernatonienė J, Masteikova R, Majiene D, Savickas A, Kevelaitis E, Bernatoniene R, et al. Free radical-scavenging activities of Crataegus monogyna extracts. Medicina (Kaunas) 2008;44:706–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milane H. La quercétine et ses dérivés: molécules à caractère pro-oxydant ou capteurs de radicaux libres; études et applications thérapeutiques [doctorate thesis]. [(Strasbourg, France)]: Université Louis Pasteur Strasbourg I; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kundan SB, Anupam S. Phytochemical Constituents and Therapeutic Potential of Allium cepa l. PHCOG Rev. 2009;3:170–80. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lebreton P, Jay M, Voirin B. Sur l’analyse qualitative et quantitative des flavonoïdes. Chim Anal. 1967;49:375–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen GC, Duh PD. Scavenging effect of methanolic extracts of peanut hulls on free radical and active oxygen. J Agric Food Chem. 1994;42:629–32. doi: 10.1021/jf00039a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. L W T- Food Sc Techn. 1995;28:25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroyer GT. Red clover extract as antioxidant active and functional food ingredient 2004. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2004;5:101–5. doi: 10.1016/S1466-8564(03)00040-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]