Abstract

Background

It is suspected that early gastric carcinoma (GC) is a dormant variant that rarely progresses to advanced GC. We demonstrated that the dormant and aggressive variants of tubular adenocarcinomas (TUBs) of the stomach are characterized by loss of MYC and gain of TP53 and gain of MYC and/or loss of TP53, respectively. The aim of this study is to determine whether this is also the case in undifferentiated-type GCs (UGCs) of different genetic lineages: one with a layered structure (LS+), derived from early signet ring cell carcinomas (SIGs), and the other, mostly poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas, without LS but with a minor tubular component (TC), dedifferentiated from TUBs (LS−/TC+).

Methods

Using 29 surgically resected stomachs with 9 intramucosal and 20 invasive UGCs (11 LS+ and 9 LS−/TC+), 63 genomic DNA samples of mucosal and invasive parts and corresponding reference DNAs were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues with laser microdissection, and were subjected to array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), using 60K microarrays, and subsequent unsupervised, hierarchical clustering. Of 979 cancer-related genes assessed, we selected genes with mean copy numbers significantly different between the two major clusters.

Results

Based on similarity in genomic copy-number profile, the 63 samples were classified into two major clusters. Clusters A and B, which were rich in LS+ UGC and LS−/TC+ UGC, respectively, were discriminated on the basis of 40 genes. The aggressive pattern was more frequently detected in LS−/TC+ UGCs, (20/26; 77%), than in LS+UGCs (17/37; 46%; P = 0.0195), whereas no dormant pattern was detected in any of the UGC samples.

Conclusions

In contrast to TUBs, copy number alterations of MYC and TP53 exhibited an aggressive pattern in LS+ SIG at early and advanced stages, indicating that early LS+ UGCs inevitably progress to an advanced GC. Cluster B (enriched in LS−/TC+) exhibited more frequent gain of driver genes and a more frequent aggressive pattern than cluster A, suggesting potentially worse prognosis in UGCs of cluster B.

Background

Gastric carcinoma (GC) have been classified histologically into intestinal, diffuse and unclassified types by Lauren [1] and the unclassified type was further divided into solid and mixed types by Carneiro [2]. The undifferentiated-type gastric carcinoma (UGC) according to the Japanese classification [3] mostly overlaps poorly differentiated GC, which comprises not only the diffuse type including signet ring cell carcinoma (SIG) but also the solid type and the mixed type with minor tubular component (TC).

Recently it has been proposed that advanced diffuse-type GC may derive from either early diffuse-type or intestinal-type GC. Well differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma (TUB) can transform into poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (POR) after the silencing of cell adhesion-related genes including CDH1[4,5]. Carneiro’s mixed type carcinomas may thus overlap dedifferentiated TUBs. It has been reported that the survival rate of the patients with mixed-type GCs was significantly lower than that of the patients with GCs of other types [2], whereas the survival rate of early GC patients with SIG was higher than that of GC patients without SIG [6]. Thus UGCs may be divided into subgroups with different prognosis. Recently, a mass-screening program for neuroblastomas [7-9] was suspended in Japan because a discontinuous genetic lineage was observed between the early- and the late-presenting neuroblastomas. Negative and late-presenting (≥1 year) neuroblastomas exhibited near-diploidy with terminal 1p deletion, whereas positive neuroblastomas in infants exhibited near-triploidy without 1p deletion [10,11]. To perform such subgrouping, we have classified UGCs based on the continuity of genetic lineages as well as the expression of morphological lineage markers.

Our lineage analysis using chromosomal comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) was based on distinctive morphological lineage markers. A layered structure (LS) represents an incipient phase of SIG development [12] and is commonly retained even at an advanced stage in the human stomach. In tumour regions with LS, the mode of cell proliferation resembles that in the normal gastric mucosa. And it is believed that tumour cells remain confined to the mucosa as far as they grow to form the LS [13]. Our lineage analyses confirmed that POR with LS was derived from intramucosal SIG, whereas POR without LS and with a minor TC (< 30%), was derived from TC [14,15]. However, the TC was not always derived from early TUB but could also be derived from SIG, whereas LS was scarcely derived from TUB [15]. Therefore, as a morphological lineage marker, LS may take priority over TC. In addition, UGCs without LS or TC due to secondary loss of these markers are observed, which prompted us to adopt array CGH (aCGH) and unsupervised cluster analyses of the aCGH data to classify UGCs solely on the basis of similarity in the genomic copy number profile.

In differentiated-type gastric carcinomas (DGCs), our recent aCGH-based lineage analyses revealed two genetic lineages: one with copy-number loss of MYC and copy-number gain of TP53 (MYC− and TP53+), a dormant pattern, and the other with the copy-number gain of MYC and/or copy-number loss of TP53 (MYC+ and/or TP53−), an aggressive pattern. The dormant pattern accounted for 70% of intramucosal carcinoma samples and a half of the intramucosal part samples of invasive carcinomas. The invasive parts of invasive carcinomas mostly exhibited the aggressive copy number alteration (CNA) pattern. When the intramucosal part of an advanced cancer was dormant, the lineage was discontinuous between the mucosal and invasive parts. Therefore, the MYC−/TP53+ and MYC+ and/or TP53− CNA patterns may be signatures of dormant and aggressive TUBs, respectively [16].

In the present study, genomic DNA samples from the mucosal and invasive parts of early and advanced UGCs were prepared and subjected to gene copy-number analyses using aCGH, followed by unsupervised cluster analysis of the aCGH data. Based on these results, we examined relationship between morphological and genetic lineage markers and identified several useful lineage marker genes for UGC.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board on Medical Ethics at Shiga University of Medical Science approved this study on the condition that the UGC samples used were anonymous. Written informed consent was not required because this retrospective study used archival samples.

Tissue samples

This study included 29 surgically resected, buffered formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded UGCs: 20 with LS in at least part of the tumour (LS+, 9 intramucosaltumours and 11 invasive tumours) and 9 without LS but containing a small TC (LS−/TC+, all invasive tumours) (Table 1). TC was defined as a well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma component comprising ≤ 30% of the entire tumour [15]. All samples were selected from GC cases diagnosed in our department from 1997 to 2011. Intramucosal LS+ UGC patients averaged 57.6 years of age (range, 48–79) and patients with invasive LS+ UGCs 60.2 years (range, 48–79) and patients with invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs 62.2 years (range; 50–75). The macroscopic classification was determined according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Cancer with TNM staging [3].

Table 1.

Summary of clinicopathological characteristics of 29 UGCs

| Case no | Age/sex | Size of mucosal lesion (cm) | Macroscopic type* | Histological type* |

Sampling region for aCGH |

Depth of invasion† | LN meta† | Stage† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intramucosal part |

Invasive part | ||||||||||

| LS | not LS | TC | |||||||||

| M101 |

79/F |

8.5 × 4.0 |

0(IIc) |

SIG > TC |

+ |

NT |

NT |

|

T1 (m) |

N0 |

IA |

| M102 |

48/F |

9.5 × 5.0 |

0(IIc) |

SIG > POR1 |

+ |

NT |

- |

|

T1 (m) |

N0 |

IA |

| M103 |

57/M |

1.4 × 0.8 |

0(IIc) |

SIG |

+ |

NT |

- |

|

T1 (m) |

N0 |

IA |

| M104 |

76/F |

6.0 × 5.0 |

0(IIc) |

SIG |

+ |

NT |

- |

|

T1 (m) |

N0 |

IA |

| M105 |

50/M |

1.5 × 1.2 |

0(IIc) |

SIG |

+ |

NT |

- |

|

T1 (m) |

N0 |

IA |

| M106 |

60/F |

1.2 × 1.0 |

0(IIc) |

SIG |

+ |

- |

- |

|

T1 (m) |

N0 |

IA |

| M107 |

49/F |

4.0 × 2.5 |

0(IIc + III) |

SIG > POR1 |

+ |

NT |

- |

|

T1 (m) |

N0 |

IA |

| M108 |

48/F |

6.0 × 2.8 |

0(IIc) |

SIG > POR1 > TC |

+ |

POR |

NT |

|

T1 (m) |

N0 |

IA |

| M109 |

51/M |

5.3 × 3.3 |

0(IIc + III) |

SIG |

+ |

SIG |

- |

|

T1 (m) |

N0 |

IA |

| SM101 |

71/F |

0.9 × 0.8 |

0(IIc) |

SIG > POR2 |

+ |

NT |

- |

NT |

T1 (sm2) |

N2 |

II |

| A102 |

72/F |

5.0 × 3.0 |

0(IIc + IIb) |

POR2 > POR1 > SIG |

+ |

SIG |

- |

POR2 |

T2 (mp) |

N1 |

II |

| A103 |

79/F |

12.0 × 8.5 |

0(IIa + IIb) |

POR1 > TC > SIG > POR2 |

+ |

POR |

NI |

NT |

T2 (mp) |

N1 |

II |

| A104 |

49/M |

2.8 × 2.5 |

0(IIc + III) |

SIG > POR2 > TC |

+ |

NT |

NT |

POR2 |

T2 (ss) |

N1 |

II |

| SM105 |

59/F |

11.5 × 7.0 |

0(IIa + IIc) |

SIG > TC > POR2 |

+ |

TUB2 |

NT |

POR2 |

T1 (sm) |

N1 |

IB |

| SM106 |

72/M |

3.7 × 2.3 |

0(IIc) |

SIG > POR1 |

+ |

POR |

- |

NT |

T1 (sm2) |

N0 |

IA |

| A107 |

48/F |

12.0 × 6.5 |

0(IIc + III) |

SIG > POR2 > POR1 > MUC |

+ |

POR |

- |

POR2 |

T3 (se) |

N2 |

IIIB |

| A108 |

46/M |

4.0 × 2.8 |

0(IIc + III) |

POR2 > POR1 > SIG |

NI |

NI |

- |

POR2 |

T2 (mp) |

N2 |

IIIA |

| A109 |

55/M |

3.8 × 3.3 |

0(IIc + III) |

SIG > POR1 |

+ |

POR |

- |

SIG |

T1 (sm2) |

N0 |

IA |

| A110 |

57/M |

5.5 × 2.2 |

0(IIc) |

POR2 > SIG > TC |

+ |

POR |

- |

POR2 |

T2 (mp) |

N1 |

II |

| A111 |

54/F |

8.0 × 7.0 |

3 |

POR2 > SIG |

+ |

POR |

- |

POR2 |

T3 (se) |

N2 |

IIIB |

| SM201 |

75/F |

3.7 × 3.0 |

2 |

POR1 > TC |

- |

POR/TUB2 |

+ |

POR |

T1 (sm2) |

N0 |

IA |

| A202 |

60/M |

4.0 × 3.8 |

0(IIc) |

POR2 > POR1 > TC > SIG |

- |

POR/TUB2 |

+ |

POR |

T2 (mp) |

N0 |

IB |

| SM203 |

71/M |

4.5 × 2.0 |

0(IIa + IIc) |

POR1 > TC > SIG |

- |

POR/TUB2 |

+ |

POR |

T1 (sm2) |

N0 |

IA |

| A204 |

65/F |

5.5 × 3.0 |

3 |

POR2 > TC > POR1 |

- |

POR/TUB2 |

+ |

POR |

T3 (se) |

N3 |

IV |

| A205 |

54/M |

7.4 × 5.8 |

5 |

POR2 > TC > POR1 |

- |

POR/TUB2 |

+ |

POR |

T3 (se) |

N0 |

II |

| A206 |

67/F |

5.5 × 4.0 |

4 |

POR2 > TC > POR1 |

- |

POR/TUB2 |

+ |

NT |

T4 (si) |

N2 |

IV |

| A207 |

52/M |

6.0 × 4.0 |

4 |

POR1 > POR2 > SIG > TC |

- |

POR/TUB2 |

+ |

POR |

T3 (se) |

N3 |

IV |

| A208 |

75/M |

9.0 × 7.0 |

2 |

POR1 > TC |

- |

POR/TUB2 |

+ |

POR |

T2 (mp) |

N1 |

II |

| A209 | 50/F | 2.3 × 0.8 | 3 | POR2 > SIG > POR1 > TC | - | POR/TUB2 | + | POR | T2 (mp) | N2 | IIIA |

*Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma, modified.

†TNM classification.

UGCs, Undifferentiated gastric carcinomas; aCGH, Array CGH; LN, Lymph node, LS, Layered structure; TC, Tubular component; SIG, Signet ring cell carcinoma; POR, Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma; POR1, Solid POR; POR2, Non-solid POR; TUB2, Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma; MUC, Mucinous adenocarcinoma; m, mucosa; sm, submucosa; mp, muscular propria; ss, subserora; se, serosal exposure; si, invasion to adjacent structures; M, Male; F, Female; NT, Not tested; NI, Not informative.

LS evaluation

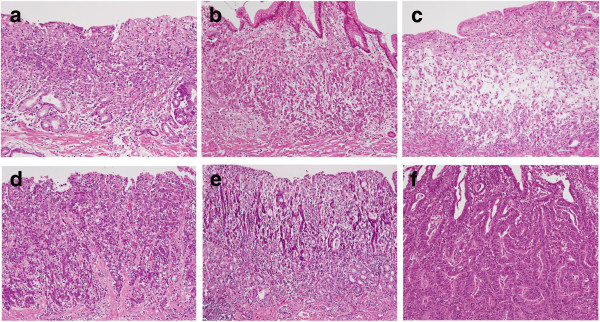

LS was defined as in a previous study [17]. In brief, LS+ regions had small carcinoma cells confined to the stroma at the gland-neck level that gradually differentiated to signet ring cells in the superficial (and deep) lamina propria (Figure 1a). The absence of LS in intramucosal regions of the tumour was defined by four patterns: 1) contact of small carcinoma cells to the muscularis mucosae in SIG, 2) mucinous adenocarcinoma, 3) POR and 4) the presence of a TC (Figure 1b-f).

Figure 1.

Histological appearances of intramucosal parts of undifferentiated-type gastric carcinomas (UGCs). A signet ring cell carcinoma (SIG) component with a layered structure in case A107 (a). Small carcinoma cells are distributed in the deeper part just above or in the muscularis mucosae in a SIG component in case M109 (b). A mucinous adenocarcinoma component in case A107 (c). A poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma component in case SM106 (d). Minor tubular components in cases SM105 and SM201, respectively (e, f).

Laser microdissection and DNA preparation

Tumour tissue samples were obtained from 5-μm-thick tissue sections using a LMD6000 laser microdissection system (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). For invasive cancers, DNA samples were obtained from both the intramucosal and invasive parts. For each sample, cancer tissues were obtained from an area >6 mm2, in which cancer cells accounted for ≥70% of the total cell count. Tissue samples were digested in 200 μg/ml proteinase K solution for approximately 72 hours at 37.0°C and genomic DNA extracted with phenol/chloroform.

Whole genome amplification

Sample DNA was amplified using the GenomePlex Whole Genome Amplification Kit (WGA2 Kit; Sigma, St. Louis, USA) [18]. For some DNA samples that could not be sufficiently amplified, the WGA5 Kit (Sigma) was employed.

Array CGH

An oligo CGH microarray (60K, 60-mer) (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) was used in this study, according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the amplified tumour and control DNA samples were non-enzymatically labelled with Cy5 and Cy3, respectively, using the Genome DNA ULS Labelling Kit (Agilent) and competitively hybridized to the microarray. The hybridized array images were captured using a DNA microarray scanner (Agilent) and then the fluorescence intensity of the tumour and control at each probe dot was calculated by Feature Extraction Ver.9.5.3 (Agilent). The array data were normalized using Genomic Workbench software Ver.5.0 (Agilent). The positions of oligomers are based on the Human Genome February 2009 assembly (hg19). Copy-number gains and losses were defined as changes in the logarithm to the base 2 of the tumour to reference signal intensity ratio (T/R) greater than 0.3219 and less than −0.3219, respectively.

Cluster analysis

To perform novel subtyping of UGC samples based on genomic profile similarity in this study, an unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis was applied across 63 samples from 29 UGC cases by using the Cluster 3.0 and TreeView software programs. The clustering algorithm was set to complete linkage clustering using an uncentered correlation. To enable unsupervised cluster analysis, we performed unbiased reduction in probe number from around 60,000 to several thousands of probes. For this purpose, we selected large genes because the greater number of corresponding probes resulted in improved signal-to-noise ratio of the representative gene copy numbers. The unsupervised strategy enabled us to set an internal standard to validate clustering results; the copy number profiles in samples of the same tumour should be more similar than any copy number profiles from another tumour because the gene alterations in the process of carcinogenesis are largely common among the samples from the same tumour.

Statistical analyses

Differences in contingency tables were assessed for statistical significance using Fisher's exact test. A P < 0.05 (2-sided) was considered statistically significant. The Welch’s t test was used to evaluate the difference in mean DNA copy number for each probe between two clusters of samples. The Bonferroni correction was used to correct for multiple comparisons.

Results

Samples analysed with array CGH

Tissue samples were excised from 29 archived GC specimens by laser microdissection. The tissue sample population included 11 regions (from 9 intramucosal SIGs), of which 9 regions were LS+ and the other two LS−, 26 regions (from 11 LS+ invasive UGC), of which 10 were LS+ mucosal regions, 8 were LS− mucosal regions and 8 were invasive regions, and 26 regions (from 9 LS−/TC+ invasive UGCs): 9 intramucosal POR, 9 intramucosal TC and 8 invasive regions.

Genome wide copy number alterations

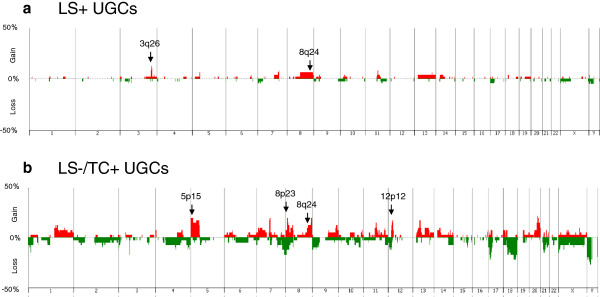

A plot of the genetic aberration penetrance for all chromosomes is shown for LS+ UGCs and LS−/TC+ UGCs in Figure 2a and Figure 2b, respectively. Copy-number gains and losses were more common in LS−/TC+ UGCs than in LS+ UGCs. The most frequent copy-number gains were detected at 3q26 (7/63 samples), 5p15 (8/63), 8p23 (9/63), 8q24 (7/63) and 12p12 (6/63), while the most frequent copy-number losses were found at 7q36 (5/63) and 12p12 (5/63).

Figure 2.

Frequency of copy-number alterations at the chromosome level. The percentage of the samples that have CNAs for each chromosome in the LS+ UGCs (a) and LS−/TC+ UGCs (b). Gains and losses are indicated with red and green, respectively.

Copy-number alterations (CNAs) common to all the samples from the same tumour were called stemline changes [14] and estimated to occur at the earliest stage of tumourigenesis and to be inherent into tumour lineage. Stemline gains of 3q26 were detected in 2/20 cases of invasive LS+ UGCs and none of invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs. In contrast, stemline gains of 5p15, 8p23 and 12p12 were detected in 2/9 cases of invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs but in no case of invasive LS+ UGCs. No stemline losses were detected in any cases of UGCs.

Previous studies using chromosomal or array CGH analyses [19-27] reported that frequent CNAs in gastric cancers (common to both UGC and DGC) were chromosomal gains at 3q, 5p, 7p, 8q, 13q, 17q, 20p and 20q, and losses at 4q, 5q, 6q, 9p, 17p, 18q and 21q. In the UGCs examined in the present study, all previously reported CNAs were observed except gains at 17q and 20p and losses at 5q and 6q. Gains at 8p and 12p were common in LS−/TC+ UGCs. Copy-number gains at 8q24 were common in both types of UGCs, with 4/20 cases of LS+ UGCs and 3/9 cases of invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs, but these were not stemline changes.

Impartial selection of genes reflecting the whole genome profile

To classify UGC samples based on the overall similarity in the profile of gene copy number changes, we used unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis. For this purpose, it was necessary to reduce the number of gene probes used in the cluster analysis from 60K to several thousands. The reduced number of genes should still reflect the whole genome profile if impartially selected. To fulfil these conditions, we selected genes based solely on the size of genes (the numbers of corresponding probes). After repeated trials of cluster analyses using genes of various minimum sizes (or probe numbers per gene), we observed that most CNAs from the same tumour were clustered more closely together than any samples from another UGC case when we analysed only genes with 3 or more probes per gene: a total of 5019 genes.

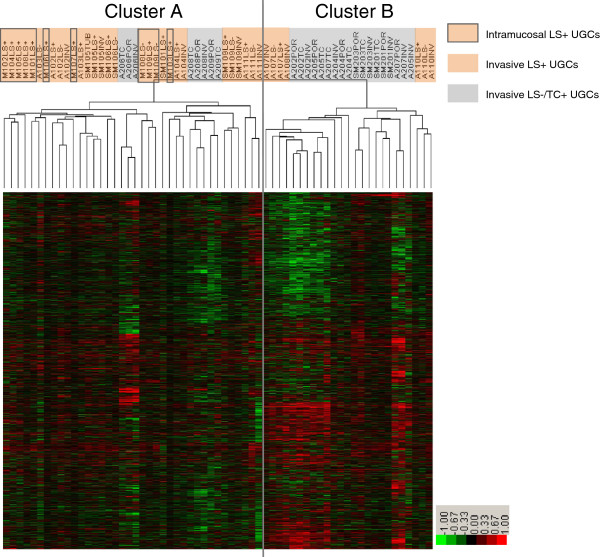

Classification of UGC using hierarchical cluster analysis

We applied an unsupervised two-dimensional hierarchical clustering algorithm, to a total of the 63 DNA samples from 29 UGCs. The samples were classified into two major clusters A and B, based on similarity in the genome profile (Figure 3). Of 63 samples, 30 LS+ UGCs were classified into cluster A and only 7 into cluster B. For LS−/TC+ UGCs, 8 samples were classified into cluster A and 18 into cluster B. All Intramucosal LS+ UGCs were included in cluster A. Clusters A and B had significantly different proportions of morphological subtypes (P = 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis of array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) data. Gene copy-number gains and losses are indicated by red and green, respectively. A total of 63 samples from 29 UGCs were classified into two major clusters: A and B. Most samples of LS+ UGCs were included in cluster A and most LS−/TC+ UGCs samples were in cluster B. All the Intramucosal LS+ UGCs were included in cluster A.

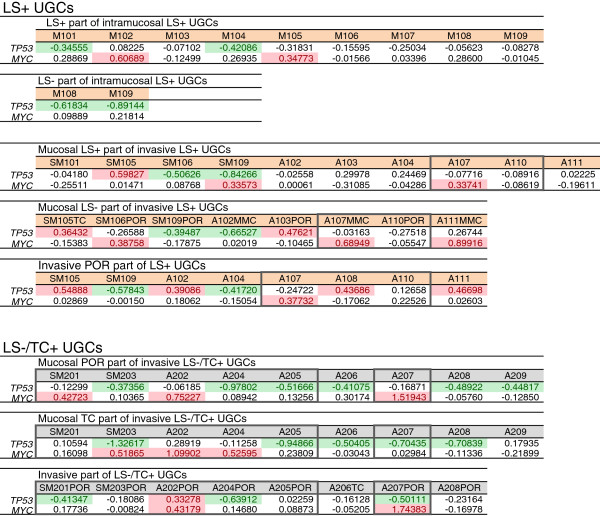

Copy number alterations of MYC and TP53

Gains at 8q24 were common alterations for both LS+ and LS−/TC+ UGCs. The representative genes located at this locus is MYC. Gains of MYC were detected in 2/11 of Intramucosal LS+ UGCs (18.2%), 6/26 of LS+ UGC (23.1%) and 8/26 of invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs (30.1%). The aggressive pattern (MYC+ and/or TP53−) was detected in 6/11 of Intramucosal LS+ UGCs (54.5%), 11/26 of invasive LS+ UGCs (42.3%) and 20/26 of invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs (76.9%; Figure 4). Therefore, the aggressive pattern was more frequently detected in invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs than in LS+ UGCs (P = 0.0195). The dormant pattern (MYC− and TP53+) was not detected in any of the UGC samples, even those from intramucosal GCs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Array CGH data of MYC and TP53 in LS+ UGCs and LS−/TC+ UGCs. LS+ UGCs are divided into intramucosal cancers and invasive cancers. Numerals mean the base 2 logarithm of the test/reference signal intensity ratios of array CGH data. Significant gains and losses are indicated with red and green, respectively. The samples marked with and without grey margin are included in cluster B and cluster A, respectively, in Figure 3.

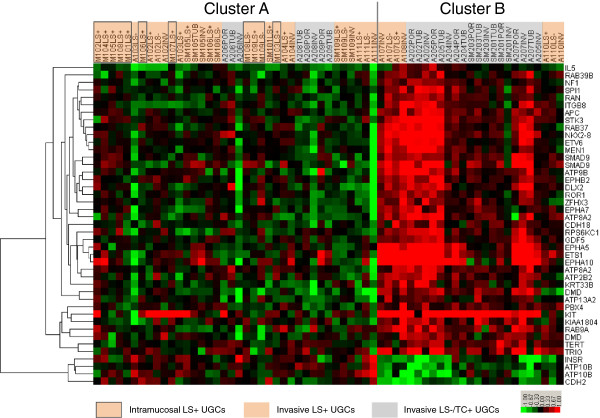

Copy number alterations of genes other than MYC or TP53

As mentioned above, 5p15 was one of the most frequent gain sites in invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs (8/26; 30.7%), but was not detected in any of the 37 intramucosal and invasive LS+ UGCs (Figure 2). The target genes located at this locus may include the telomerase reverse transcriptase gene (TERT) because a TERT gain was more frequently detected in invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs than intramucosal and invasive LS+ UGCs (16/26 vs. 1/37, P < 0.0001) (Figure 5). In contrast, losses of TERT were detected in 4/37 samples of intramucosal and invasive LS+ UGCs (10.8%) but not in invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs.

Figure 5.

Array CGH data of genes other than MYC and TP53 with significantly different T/R ratio between clusters A and B. UGCs are divided into clusters A and B that were determined in Figure 3. The heat map indicates the base 2 logarithm of the test/reference signal intensity ratios of array CGH data. Gains and losses are indicated with red and green, respectively.

Welch’s t test was performed to compare the mean T/R ratio between the samples in cluster A and those in cluster B at each 2756 probe loci of 979 cancer-related genes. Fourty-three gene probes, belonging to 40 genes, had significantly different mean T/R ratios between Clusters A and B at a level of P < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction (Table 2). Of the 40 genes, 6 genes (KIT, RAN, RAB39B, RAB9A, RAB37 and TERT), including proto-oncogenes, have been implicated in enhanced tumour growth, and 8 genes (ETS1, SPI1, ETV6, EPHA7, EPHA5, EPHB2, EPHA10 and TRIO) in invasion/metastasis and 3 genes (APC, NF1 and MEN1) in tumour suppression (Table 2). Most of log2 T/R ratios of the 43 distinguishing gene probes were of opposite sign between clusters A and B, with greater in absolute values in cluster B (Figure 5).

Table 2.

List of 40 genes that have CNAs significantly different between clusters A and B

| Probe name | Location | Name of Gene | Description | P-value | P value after Bonferroni correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A_16_P41637097 |

Xp21.2 |

DMD |

dystrophin |

4.541E-08 |

1.251E-04 |

| A_14_P133591 |

5q21-q22 |

APC |

adenomatous polyposis coli |

5.774E-08 |

1.591E-04 |

| A_14_P130973 |

4q11-q12 |

*KIT |

v-kit Hardy-Zuckerman 4 feline sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

1.047E-07 |

2.886E-04 |

| A_14_P125447 |

13q12-q14 |

SMAD9 |

SMAD family member 9 |

1.373E-07 |

3.784E-04 |

| A_14_P100439 |

12q24.3 |

*RAN |

member RAS oncogene family |

1.876E-07 |

5.171E-04 |

| A_14_P102616 |

20q11.2 |

GDF5 |

growth differentiation factor 5 |

2.828E-07 |

7.794E-04 |

| A_14_P133647 |

11q23.3 |

**ETS1 |

v-etserythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 1 (avian) |

5.603E-07 |

0.0015 |

| A_14_P138640 |

5p14.3 |

CDH18 |

cadherin 18, type 2 |

6.138E-07 |

0.0017 |

| A_14_P128664 |

18q23 |

ATP9B |

ATPase, class II, type 9B |

6.474E-07 |

0.0018 |

| A_14_P124801 |

19p12 |

PBX4 |

pre-B-cell leukemia homeobox 4 |

1.010E-06 |

0.0028 |

| A_14_P118423 |

Xq28 |

*RAB39B |

member RAS oncogene family |

1.573E-06 |

0.0043 |

| A_14_P134602 |

17q11.2 |

NF1 |

neurofibromin 1 |

1.802E-06 |

0.0050 |

| A_14_P120351 |

5q31.1 |

IL5 |

interleukin 5 (colony-stimulating factor, eosinophil) |

1.988E-06 |

0.0055 |

| A_14_P125637 |

6q16.1 |

**EPHA7 |

EPH receptor A7 |

2.153E-06 |

0.0059 |

| A_14_P100300 |

13q12-q14 |

SMAD9 |

SMAD family member 9 |

2.525E-06 |

0.0070 |

| A_14_P201681 |

7p21.1 |

ITGB8 |

integrin, beta 8 |

2.589E-06 |

0.0071 |

| A_14_P130112 |

Xp22.2 |

*RAB9A |

RAB9A, member RAS oncogene family |

2.949E-06 |

0.0081 |

| A_14_P120484 |

1q41 |

RPS6KC1 |

ribosomal protein S6 kinase, 52 kDa, polypeptide 1 |

3.052E-06 |

0.0084 |

| A_16_P16709446 |

4q13.1 |

**EPHA5 |

EPH receptor A5 |

3.584E-06 |

0.0099 |

| A_14_P201127 |

2q32 |

DLX2 |

distal-less homeobox 2 |

3.703E-06 |

0.0102 |

| A_14_P126957 |

11p11.2 |

**SPI1 |

spleen focus forming virus (SFFV) proviral integration oncogene |

4.334E-06 |

0.0119 |

| A_14_P104667 |

8q22.2 |

STK3 |

serine/threonine kinase 3 |

4.386E-06 |

0.0121 |

| A_14_P137889 |

14q13.3 |

NKX2-8 |

NK2 homeobox 8 |

5.393E-06 |

0.0149 |

| A_14_P109970 |

1p36.1-p35 |

**EPHB2 |

Eph receptor B2 |

6.637E-06 |

0.0183 |

| A_14_P118116 |

Xp21.2 |

DMD |

dystrophin |

8.087E-06 |

0.0223 |

| A_16_P01378894 |

5q34 |

ATP10B |

ATPase, class V, type 10B |

8.165E-06 |

0.0225 |

| A_14_P139456 |

17q25.1 |

*RAB37 |

member RAS oncogene family |

1.001E-05 |

0.0276 |

| A_14_P111361 |

17q21.2 |

KRT33B |

keratin 33B |

1.069E-05 |

0.0295 |

| A_14_P134909 |

19p13.3-p13.2 |

INSR |

insulin receptor |

1.110E-05 |

0.0306 |

| A_16_P02740008 |

13q12 |

ATP8A2 |

ATPase, aminophospholipid transporter, class I, type 8A, member 2 |

1.129E-05 |

0.0311 |

| A_14_P102858 |

1q42 |

KIAA1804 |

mixed lineage kinase 4 |

1.155E-05 |

0.0318 |

| A_14_P113857 |

12p13 |

**ETV6 |

ets variant 6 |

1.172E-05 |

0.0323 |

| A_14_P115054 |

16q22.3 |

ZFHX3 |

zinc finger homeobox 3 |

1.180E-05 |

0.0325 |

| A_14_P138431 |

1p32-p31 |

ROR1 |

receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1 |

1.209 E-05 |

0.0333 |

| A_18_P22746653 |

3p25.3 |

ATP2B2 |

ATPase, Ca++ transporting, plasma membrane 2 |

1.282E-05 |

0.0353 |

| A_14_P105811 |

11q13 |

MEN1 |

multiple endocrine neoplasia I |

1.318E-05 |

0.0363 |

| A_14_P136621 |

18q11.2 |

CDH2 |

cadherin 2, type 1, N-cadherin (neuronal) |

1.420E-05 |

0.0391 |

| A_14_P103176 |

1p34.3 |

**EPHA10 |

EPH receptor A10 |

1.455E-05 |

0.0401 |

| A_16_P17370843 |

5q34 |

ATP10B |

ATPase, class V, type 10B |

1.556E-05 |

0.0429 |

| A_14_P108129 |

5p15.33 |

*TERT |

telomerase reverse transcriptase |

1.584E-05 |

0.0436 |

| A_16_P19750359 |

13q12 |

ATP8A2 |

ATPase, aminophospholipid transporter, class I, type 8A, member 2 |

1.586E-05 |

0.0437 |

| A_14_P200005 |

1p36 |

ATP13A2 |

ATPase type 13A2 |

1.586E-05 |

0.0437 |

| A_16_P01183532 | 5p15.2 | **TRIO | trio Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor | 1.786E-05 | 0.0492 |

In the column of gene name, “*” indicates genes related to tumour growth and “**” those related to invasion and metastasis.

Discussion

Based on chromosomal CGH analysis, we have reported that there are two distinct UGC lineages: the LS+ lineage derived from early SIG and LS−/TC+ lineage dedifferentiated from TUB [15]. The former is characterized by LS and the latter by a small TC. However, there are also UGCs without these morphological lineage markers. In the present study, we classified UGC based on similarity in the whole genome copy number profile among samples using unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis and examined the correlation between this gene-based classification and morphological lineage markers.

Using 5019 large genes and aCGH data from 63 DNA samples from 29 UGCs, we confirmed that most of the samples examined from the same tumour were clustered more closely together than in any other sample, thus fulfilling the criteria for our internal standard. On the basis of this observation, we performed an unsupervised two-dimensional hierarchical cluster analysis. All the samples were classified into two major clusters A and B (Figure 3). Cluster A was rich in LS+ UGCs, whereas cluster B was rich in LS−/TC+ UGCs. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.0001) and indicates that the classification by the presence or absence of LS and TC is well correlated with the genomic-profile-based classification and validates the LS+ and LS−/TC+ as lineage markers.

All the intramucosal LS+ UGCs were included in cluster A, suggesting that most of UGCs in cluster A were derived from intramucosal SIG, and that the LS−/TC+ UGCs in cluster A may have secondarily lost LS. The LS−/TC+ UGCs in cluster A may also be derived from SIG, as suggested by chromosomal CGH studies [15]. In contrast, LS in advanced LS+ UGCs in cluster B (A107, A108 and A110) was virtually indistinguishable morphologically but showed genomic constitutions different from LS in cluster A. This may be a kind of phenocopy; a fraction of LS+ UGCs were considerably similar in genomic profile to LS−/TC+ UGCs. Although LS exhibits regular cell proliferation and differentiation and a superficially spreading dormant growth [13], it is suggested that LS itself is not a marker of persistent tumour dormancy but has the potential to progress to an advanced stage with the prognosis as poor as that for LS−/TC+ UGCs. This situation may resemble that in chronic myeloid leukaemia, in which blastic transformation occurs after a dormant phase of well retained cellular differentiation.

Most UGCs exhibited the aggressive genomic pattern (TP53− and/or MYC+), even 55% of intramucosal LS+ UGCs, an incidence comparable to that in invasive UGCs. The dormant pattern (MYC− and TP53+) was not detected in any of the UGC samples, even in intramucosal UGCs. These intramucosal UGCs are distinct from early DGCs, in which 70% are of the dormant type [16]. Therefore, TP53 and MYC are not as useful prognostic markers for UGCs.

To explore other genes important for differentiation of genetic lineage and for UGC prognosis, we first compared the profiles of chromosomal copy-number alterations (CNAs) between LS+ and LS−/TC+ UGCs. As shown in Figure 2, CNAs detected in LS+ tumours but not in LS−/TC+ tumours, include 3q26 gain, a locus likely to include SKIL because the average SKIL copy number was greater in LS+ tumours than in LS−/TC+ tumours (P = 0.0060). SKIL encodes SnoN protein that is proto-oncogenic by antagonizing cytostatic responses of TGF-β [28,29] and anti-oncogenic by activating p53 [30]. Those CNAs with the opposite pattern (present in LS−/TC+ tumours but not in LS+ tumours) were gains at 5p15, 8p23 and 12p12. The target genes at 5p15 and 12q12 include TERT, and KRAS, respectively because gains of TERT, and KRAS were more frequently detected in invasive LS−/TC+ UGCs than intramucosal and invasive LS+ UGCs (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0032, respectively). No target gene was detected at 8q23.

Our second approach to identify lineage-specific CNAs was a screening of genes (from 979 cancer-related genes) that indicated significantly different mean T/R ratios between the samples of clusters A and B. We selected 40 genes that were significantly different between clusters (using t test after Bonferroni correction), of which 6 were related to enhanced tumour growth and 8 to invasion/metastasis (Table 2). As shown in Figure 5, genes that drive tumourigenesis were more common in cluster B and showed larger amplitude CNAs. Thus, UGCs in cluster B may be more dependent on oncogenic genomic alterations and less on environmental and epigenetic alterations than those in cluster A.

The possible drivers of tumour growth screened included KIT, TERT, and RAS family genes. KIT encodes a receptor tyrosine kinase that is activated by stem cell factor binding and initiates numerous signal transduction pathways linked with the process of apoptosis, proliferation and tumorigenesis [31]. RAS family genes encode small GTPase that plays a key role in transduction of signals from receptor kinase to the pathways of various cellular processes [32]. TERT encodes the telomerase catalytic subunit that plays not only an important role in cellular immortalization by telomere elongation [33,34] but also activates cell proliferation [35]. The possible drivers of invasion and metastasis screened include ETS1 and Ephrin receptor genes. ETS1 encodes a transcription factor, Ets1 proto-oncoprotein that promotes invasiveness and is an indicator of poor outcome in epithelial cancers through regulation of MMP1, MMP3, MMP9, uPA, VEGF and VEGF receptor expression [36]. Ephrin receptor genes, EPH39B, A7, A5 and A10 genes encode the ephrin receptor with tyrosine kinase activity that affects tumor growth, invasiveness, angiogenesis, and metastasis [37].

There were no significant differences in the mean copy number of CDH1 and its transcriptional repressor genes (SNAI1, SNAI2, ZEB1, ZEB2, TWIST1, etc.) between the clusters A and B, although these genes were reportedly associated with a poorly differentiated phenotype and poor clinical outcome [38]. However, these genes may still participate in UGC tumourigenesis through epigenetic silencing [39].

We are now extending this study to to validate UGC-associated genes as indicated by aCGH by quantitative PCR and to correlate their genomic copy number to gene expression and prognosis. Thereafter, using quantitative PCR analyses instead of aCGH, similar analyses should be applied to a greater number of tumour cases with known outcomes.

Conclusions

Unsupervised cluster analyses of aCGH data of multiple samples from early and advanced UGCs have demonstrated that early UGCs, including LS+ types in which polarity of cell proliferation and differentiation is well retained, have aggressive potential. Therefore, eradication of UGCs at early stages may thus contribute to better patient survival. In addition, it was observed that the two UGC lineages, one derived from early SIG and the other from TUB, have different genomic copy-number alteration profiles, resulting in different sets of genes contributing to tumourigenesis. The latter lineage from TUB may be more dependent on genomic copy-number alterations and have a poorer outcome than UGCs derived from SIG.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AS performed most of the experiments, participated in the experimental design performed most of the data analyses and drafted the manuscript. KM participated in sample preparation for array CGH. TN participated partly in cluster analysis. VTND participated in varying selections of genes for cluster analysis, and TH, AA and YF provided critical comments and suggested revisions to the manuscript. HS conceived the study, designed the research route, and guided the experiments and the data analyses. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Ayano Sonoda, Email: ayano@belle.shiga-med.ac.jp.

Ken-ichi Mukaisho, Email: mukaisho@gmail.com.

Takahisa Nakayama, Email: 330601@belle.shiga-med.ac.jp.

Vo Thi Ngoc Diem, Email: votngocdiem@gmail.com.

Takanori Hattori, Email: hattori.takanori@gmail.com.

Akira Andoh, Email: andoh@belle.shiga-med.ac.jp.

Yoshihide Fujiyama, Email: fujiyama@belle.shiga-med.ac.jp.

Hiroyuki Sugihara, Email: sugihara@belle.shiga-med.ac.jp.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express cordial thanks to Professor Yataro Daigo, Shiga University of Medical Science, for several suggestions on hierarchical cluster analysis. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C-21590369, C-25460454) from the Japan Society of the Promotion of Science.

References

- Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histoclinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro F. Classification of gastric carcinomas. Curr Diagn Pathol. 1997;4:51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0968-6053(97)80008-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh Y, Tamura G, Watanabe H, Ajioka Y, Motoyama T. The common 18-base pair deletion at codons 418-423 of the E-cadherin gene in differentiated-type adenocarcinomas and intramucosal pre cancerous lesions of the stomach with the features of gastric foveolar epithelium. J Pathol. 1999;189:201–206. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199910)189:2<201::AID-PATH409>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Shimoda T, Nakanishi Y, Ochiai A, Toda G. Histologic heterogeneity and mucin phenotypic expression in early gastric cancer. Pathol Int. 2001;51:165–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2001.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuji E, Yamaguchi T, Sawai K, Takahashi T. Characterization of Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma of the Stomach. J Surg Oncol. 1998;67:216–220. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199804)67:4<216::AID-JSO2>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada T, Nakata T, Takasugi N, Maeda K, Hanawa Y, Shimizu K, Hirayama M, Takeda T, Mori T, Koide R, Tsunoda A, Nagahara N, Yamamoto K. Mass screening for neuroblastoma in infants in Japan. Interim report of a mass screening study group. Lancet. 1984;2:271–273. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada T, Sugimoto T, Tanaka T, Kawakatsu H, Ishii T, Matsumura T, Horii Y. Number and cure rate of neuroblastoma cases detected by the mass screening program in Japan: future aspects. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1987;15:14–17. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950150104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SB, Cohn SL, Craft AW, Woods WG, Sawada T, Castleberry RP, Levy HL, Prorok PC, Hammond GD. Do children benefit from mass screening for neuroblastoma? Consensus Statement from the American Cancer Society Workshop on Neuroblastoma Screening. Lancet. 1991;337:344–346. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90957-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y, Kanda N, Maseki N, Sakurai M, Tsuchida Y, Takeda T, Okabe I, Sakurai M. Different karyotypic patterns in early and advanced stage neuroblastomas. Cancer Res. 1987;47:311–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y, Kobayashi H, Watanabe N, Tomioka N, Nakagawara A. Biology of neuroblastomas that were found by mass screening at 6 months of age in Japan. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:285–291. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara H, Hattori T, Imamura Y, Noriki S, Fukuda M, Katsura K, Tsuchihashi Y, Fujita S. Morphology and modes of cell proliferation in earliest signet ring cell carcinomas induced in canine stomachs by N-ethyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1991;117:197–204. doi: 10.1007/BF01625425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara H, Hattori T, Fukuda M, Fujita S. Cell proliferation and differentiation in intramucosal and advanced signet ring cell carcinomas of the human stomach. Virchows Arch A. 1987;411:117–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00712735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng DF, Sugihara H, Mukaisho K, Tsubosa Y, Hattori T. Alterations of chromosomal copy number during progression of diffuse-type gastric carcinomas: metaphase- and array-based comparative genomic hybridization analyses of multiple samples from individual tumours. J Pathol. 2003;201:439–450. doi: 10.1002/path.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng DF, Sugihara H, Mukaisho K, Ling ZQ, Hattori T. Genetic lineage of poorly differentiated gastric carcinoma with a tubular component analysed by comparative genomic hybridization. J Pathol. 2004;203:884–895. doi: 10.1002/path.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama T, Ling ZQ, Mukaisho K, Hattori T, Sugihara H. Lineageeanalysis of early and advanced tubular adenocarcinomas of the stomach: continuous or discontinuous? BMC Cancer. 2010;10:311–321. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsagdorj L, Sugihara H, Bamba M, Hattori T. Intratumoural heterogeneity of intestinal expression reflects environmental induction and progression-related loss of induction in undifferentiated-type gastric carcinomas. Histopathology. 2008;53:685–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SE, Vuononvirta R, Reis-Filho JS, Natrajan R, Iravani M, Fenwick K, Mackay A, Ashworth A, Pritchard-Jones K, Jones C. Array CGH using whole genome amplification of fresh-frozen and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor DNA. Genomics. 2006;87:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi Y, Tanaka S, Mou R, Koganei H, Kokawa A, Kitamura R, Yamauchi H, Ookubo K, Saito T, Tominaga S, Matsumura K, Shimada H, Tsuchida N, Sekihara H. Changes in DNA copy number in primary gastric carcinomas by comparative genomic hybridization. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:1067–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakura C, Mori T, Sakabe T, Ariyama Y, Shinomiya T, Date K, Hagiwara A, Yamaguchi T, Takahashi T, Nakamura Y, Abe T, Inazawa J. Gains, losses, and amplifications of genomic materials in primary gastric cancers analyzed by comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;24:299–305. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199904)24:4<299::AID-GCC2>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Grieken NC, Weiss MM, Meijer GA, Hermsen MA, Scholte GH, Lindeman J, Craanen ME, Bloemena E, Meuwissen SG, Baak JP, Kuipers EJ. Helicobacter pylori-related and -non-related gastric cancers do not differ with respect to chromosomal aberrations. J Pathol. 2000;192:301–306. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH697>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y, Noguchi T, Kawahara K, Kashima K, Daa T, Yokoyama S. Genetic alterations in 102 primary gastric cancers by comparative genomic hybridization: gain of 20q and loss of 18q are associated with tumor progression. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1328–1337. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka S, Yasutake T, Kondo M, Takeshita H, Yano H, Haseba M, Tsuji T, Sawai T, Nakagoe T, Tagawa Y. Frequent gains of 20q and losses of 18q are associated with lymph node metastasis in intestinal-type gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3353–3357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada H, Imoto I, Tsuda H, Sonoda I, Ichikura T, Mochizuki H, Okanoue T, Inazawa J. Screening of DNA copy-number aberrations in gastric cancer cell lines by array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:100–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Jeung HC, Jeong HJ, Choi YH, Kim JE, Jung JJ, Rha SY, Yang WI, Chung HC. Identification of genes with correlated patterns of variations in DNA copy number and gene expression level in gastric cancer. Genomics. 2007;89:451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan B, Dachrut S, Coral H, Yuen ST, Chu KM, Law S, Zhang L, Ji J, Leung SY, Chen X. Integration of DNA copy number alterations and transcriptional expression analysis in human gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi E, Klersy C, Manca R, Zuffardi O, Solcia E. Correlation between genomic alterations assessed by array comparative genomic hybridization, prognostically informative histologic subtype, stage, and patient survival in gastric cancer. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1937–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deheuninck J, Luo K. Ski and SnoN, potent negative regulators of TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:47–57. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahchan NS, Luo K. SnoN in mammalian development, function and diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10(6):670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahchan NS, Ouyang G, Luo K. Expression Profiles of SnoN in Normal and Cancerous Human Tissues Support Its Tumor Suppressor Role in Human Cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich MC, Rubin BP, Longley BJ, Fletcher JA. Biology and genetic aspects of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: KIT activation and cytogenetic alterations. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:484–495. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.124124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal R, Jurisica I, Mills GB, Cheng KW. The Emerging Role of the RAB25 Small GTPase in Cancer. Traffic. 2009;10(11):1561–1568. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SB, Graham ME, Lovrecz GO, Bache N, Robinson PJ, Reddel RR. Protein composition of catalytically active human telomerase from immortal cells. Science. 2007;315:1850–1853. doi: 10.1126/science.1138596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgin LM, Reddel RR. Telomere maintenance mechanisms and cellular immortalization. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:97–103. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin KY, Cheung P, Gilison D, Lee E, Tennen RI, Wang E, Artandi MK, Oro AE, Artandi SE. Conditional telomerase induction causes proliferation of hair follicle stem cells. Nature. 2005;436:1048–1052. doi: 10.1038/nature03836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgen D. The Biology of the Ets1 Proto-Oncogene. Mol Cancer. 2003;2:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer: bidirectional signaling and Beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(3):165–180. doi: 10.1038/nrc2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humar B, Guilford P. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: a manifestation of lost cell polarity. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1151–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont N, Wilson MB, Crawford YG, Reynolds PA, Sigaroudinia M, Tlsty TD. Sustained induction of epithelial to mesenchymal transition activates DNA methylation of genes silenced in basal-like breast cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14867–14872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807146105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]