Abstract

There are some key figures in medical history whose achievements can be regarded as crucial in the definition of new knowledge and in setting new standards for clinical practice. This manuscript depicts the lives and work of three eminent physicians who were forerunners in the foundation of orthopaedics as an independent medical specialty. They are: Nicholas Andry, Jean-Andrè Venel, and John Ball Brown. The first was the inventor of the name of our discipline, whereas the other two, besides being renowned practitioners, were also the founders, respectively, of the first orthopaedic institutions in Europe and the United States. Therefore, they can be included among the illustrious fathers of modern orthopaedic practice.

“FIAT ORTHOPAEDIA”: Introduction

Medicine can be regarded as the “human science” par excellence. The development of medical knowledge has always been a topic of particular interest since medical history is not just a source of attractive anecdotes and curious biographies—looking back to the great medical figures of the past it is possible to find some true geniuses whose intuition helped to shape the world as we know it and whose contribution opened new paths of research, responsible for the great achievements of the present. Although some of these personalities are well known and properly remembered, there are others who are less celebrated, even if their lives often made a remarkable contribution to setting new standards of medical practice, thus marking a radical shift with respect to tradition. Nowadays “medicine” is a generic word; it includes all the clinical and surgical specialties, but it was not so in the past. In fact, for example, there were no clear distinctions among the various surgical branches and the “old-school” surgeon was able to perform abdominal procedures as well as urological, orthopaedic, and vascular operations [1]. But as medical knowledge drastically increased over time with incredible technological improvement, specific skills required specific professional figures to ensure the best scientific and clinical outcome—that is the foundation of medical specialties, which are the basis of modern health systems. There are some eminent figures who can be considered “fathers” or the “forerunners” of some particular medical or surgical branches. Their work, their discoveries, and their achievements were so astounding that they impressed future generations and inspired them to follow those peculiar areas of research and practice. In the case of orthopaedic surgery it is possible to identify several “pioneers”, but some of them are less well known and deserve recognition: to their devotion and commitment we owe the brightness of our current discipline. Orthopaedic practice dates back to the very origins of human civilisation, with some orthopaedic reports coming from Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece [2]. However, the path to achieve “independence” from other medical specialties was very long. The word “orthopaedics” itself was first established in the early 18th century and, strangely, it does not contain any direct reference to muscles, tendons and bones, which are the subject of orthopaedic practice. In this paper we describe the lives and the works of three Masters, two from Europe and one from the USA; for different reasons, their pioneering contributions helped to establish modern orthopaedics, and their examples deserve to be properly remembered to give us greater awareness of the roots of our discipline.

“IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD”: Nicholas Andry

The name of Nicolas Andry is at the top of every general textbook about orthopaedics, it is the ice pick used to start a basic level of learning, often no more than an anecdote, a curiosity regarding the name of our scientific field.

Andry was born in Lyon in 1658 as the third son of a modest family of merchants [3]. Because of his humble beginnings he might have become a priest, but his strong and opinionated character prompted him to study medicine at the Faculty of Rheims, in 1690, at the age of 32.

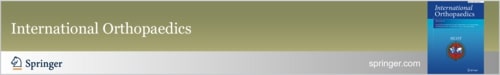

Whether Andry is the ‘father of orthopaedics’ is a moot point, as according to several important scholars [4], he just got lucky about the name and the iconic symbol of the crooked tree (Fig. 1). Without this fortunate insight his name and works would have been soon forgotten; however, there are such a vast amount of papers and studies about him, that we cannot really disregard him as a marginal note in our history.

Fig. 1.

“L’Orthopédie” by Nicholas Andry (original French titled page) and the “Crooked Tree”, symbol of Orthopaedics and many orthopaedic organisations

Andry was a conflicted man, eager to make a name for himself among his contemporaries; we know more about his polemic writings than about his life. The information we have is mostly from his enemies who were far from sympathetic about his character and personality: haughty, contemptuous, ignorant, burdensome, quick-tempered, and envious… just to quote a few of them [5].

We do not even know what he looked like; there is a dubious [5] portrait of him by De Troy in the collection of the Paris Faculty of Medicine. The only real representation of Andry is a satirical cartoon at the French National Library depicting him as the ‘Homini Verminoso’ because of his studies on parasitology. Maybe Andry is not the father of orthopaedics, but he is the father of parasitology [3]. His 1700 book “De la géneration des vers dans le corps de l’homme. De la nature et des espèces de cette maladie, les moyens de s’en preserver et de la guérir” [6] is the origin of that science.

Going back to the ‘debate’, in 1741, a year before his death in Paris, Nicolas Andry published a meaningful book about a medical field that was, until that moment, without name or boundaries: ‘Orthopédie’ or the ‘art of correcting and preventing deformities in children’ [7]. A neologism coined by combining two Greek words: orthos (straight, correct) and paidos (children).

That ill-spoken man, the object of many mockeries and taunts, wrote a book aimed not at surgeons or scientists, but at loving parents, giving advice and suggestions of how to take care of their sons and daughters.

“…one must not neglect the body and let it become deformed, this would be against the intention of the Creator; this is the basic principle of orthopaedics […] this book is aimed exclusively at fathers and mothers and all people bringing up children who must try to prevent and correct any deformed part of the child body” [7].

The book is divided into four parts, and the first edition is published in two volumes: the first part is “an Introduction to the other three, and contains a general Notion of the external Parts of the Body”, where many of the ideas at the origin of Andry’s theories come from the research by Leonardo Da Vinci [8]; the following part “has for Object the Art of preventing and correcting, in particular, the Deformities of the Shape, with respect to the trunk of the Body”, the third “concerns the Deformities of the Arms, the Hands, the Legs and the Feet”. This is the part that contains a very well-known quote, in many ways the real legacy left by Andry to modern orthopaedics: “[…] In a word, the same Method must be used in this Case, for recovering the Shape of the Leg, as is used for making straight the crooked trunk of a young Tree”, the famous illustration of the Crooked Tree (Fig. 1), reminiscent of Alexander Pope rhyme “Tis education forms the common mind: just as the twig is bent, the tree’s inclined” [9]. We cannot really disprove the bad traits in Andry’s lifestyle, but we can certainly attest he was not an ignorant or a cold-hearted man. We remember his book for its title, some great figures and a quote or two, nothing more truly resonates in modern orthopaedics, but the impressions and feelings evoked by those symbols are beyond any doubt landmarks in the history of our discipline.

The fourth part of his treatise is dedicated to the head and face. The whole book is filled with notions that today we would call ‘paediatric orthopaedics’, but they were not less modern and revolutionary for their time, and still pertinent for whoever wants to understand, to fully grasp the meaning and purpose of orthopaedics.

“AND LET THE DRY LAND APPEAR”: Jean Andre’ Venel

The other ‘father’ of orthopaedics [10], the founder of the first orthopaedic institution in medical history, was Jean-André Venel (Fig. 2), an obstetrician turned orthopaedist to give a new and more dedicated impetus to the development of the branch of medicine named by Nicolas Andry.

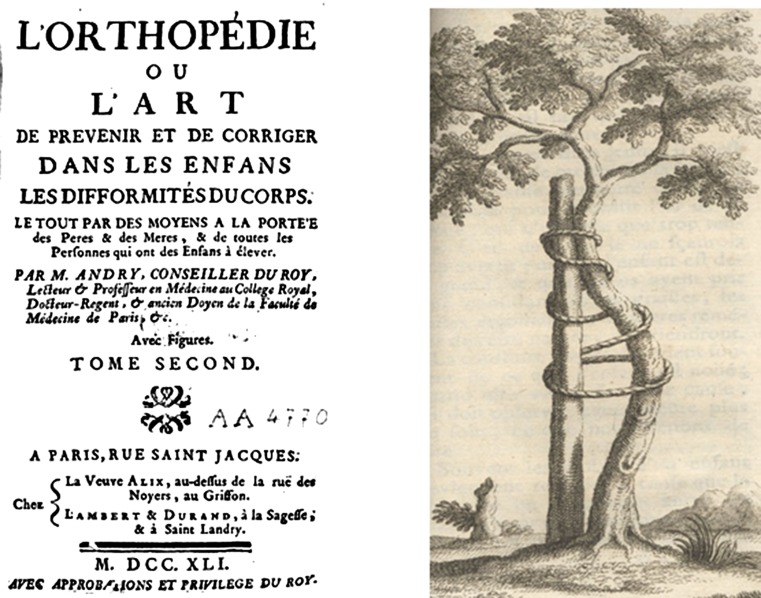

Fig. 2.

Jean Andrè Venel, 1790 portrait by Christoph Bock, and The Great Abbaye of Orbe, the first orthopaedic hospital in history

Venel was born in Morges (Switzerland) in 1740, son of a surgeon-barber. In 1756 he moved to Geneva to study surgery and was an obstetrician under Francois-David Cabanis (1727–1794). Years later, he started to feel scorn for the poor education of midwives, their lack of training and the many avoidable accidents involved in childbirth. Venel’s attitude is important to understand all his career and life choices: he wrote a book [11], which was a manual aimed at teaching the art of midwifery. He fought the government and won the right to open a school of midwifery. By outstanding determination he strove to improve his time and society, to take every necessary step to guarantee the circulation of medical knowledge and better training for medical operators.

The story goes [12] that in 1776, a friend of Venel brought him his seven-year-old son, afflicted by severe deformities (clubfoot on the right and pes valgus on the left side) that nobody could fix. After a year of treatment under the care of Dr. Venel, the deformities were perfectly corrected. Venel began to master his knowledge of anatomy and the still nebulous topic of orthopaedics, by recognising that here was a situation similar to that of midwifery that he had addressed earlier. He bought Abbaye, an old building above the town of Orbe in the Swiss canton of Vaud and in 1780 established the first orthopaedic hospital in history.

A brief description of the institution was reported by English historian William Coxe [12]:

“It is an infirmary for the reception of those objects who are born with distorted limbs, or owe that misfortune to accident […] The children are lodged and boarded in the house, under the care of his (Venel’s) assistant, who charges himself with all detail of housekeeping, and instructing those, whose age renders it requisite that their education should not be neglected. […] Though he (Venel) chiefly confines his attempts to infants and children, […] he has performed several cures on adults. His most efficacious remedy is a machine which he has invented to embrace the patients’ limbs when in bed, and which is contrived to act without disturbing their rest. Ingenious as his method is, yet he acknowledges, that much of his success depends on mild treatment and continual inspection. I was convinced indeed of the mildness of his treatment, by observing several of these children, from four to ten years of age, crawling about the ground, and diverting themselves with great cheerfulness, although cased up in their machinery. […] Such establishment redounds highly to the honour of M. Venel, and the government who protects it, and is worthy of imitation in all countries.”

…as we shall see later.

Venel’s hospital quickly became known throughout Europe and around the world, thus showing the long-time necessity for orthopaedic specialists and experience, and even attracting the attention of the prince of Nassau who requested help.

Unfortunately, the hospital was far too dependent on Venel and failed to survive long after his death in 1791 from pulmonary tuberculosis, and closed in 1820.

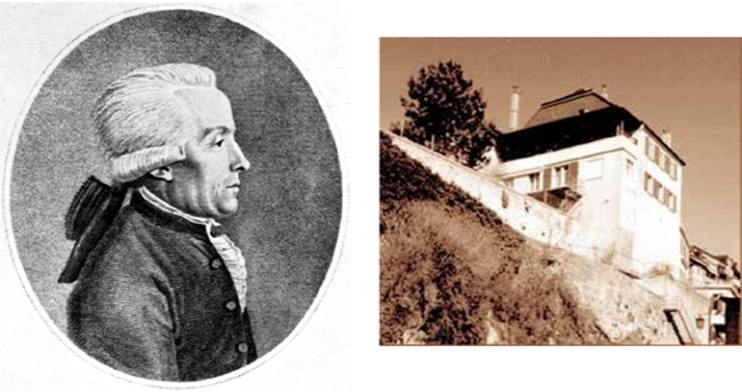

Following in Andry’s footsteps, Venel’s orthopaedic theories and studies focused on the treatment of deformities, particularly through the use of machines and orthotics of his own invention; he was a mechanical genius who produced machinery of every kind, from the hydraulic system of the hospital [13] to chimneys [14], and from chemical ovens [15] to instruments designed to extract foreign bodies from the oesophagus [16].

In orthopaedics, this talent and ingenuity led to the invention of the ‘press of Venel’ (later known as the ‘sabot of Venel’) to reduce the clubfoot; this instrument was used for 200 years and consisted of two parts: ‘a rod along the outside of the lower part of the leg’ and ‘a plate fixed to the end of this rod that attached to the foot and pushed it slowly into the desired position’ [12].

Venel was also the creator of the ‘Appareil du jour’ (daytime apparatus), a system of braces to treat scoliosis that, for the first time in history, allowed the lateral deviations and torsions of the spine to be reduced together. This machine, according to Venel, would have to be used jointly with another of his inventions—the first orthopaedic bed in the world, or ‘Appareil de nuit’ (nighttime apparatus). The innovation of Venel’s treatment for scoliosis was to switch to a 24-hour care of the deformity, by applying little but constant force to reduce it more successfully (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Venel’s inventions: Appareil du jour; Appareil de nuit; Press/Sabot of Venel

Venel’s influence was felt throughout the 19th century and even today we can still find elements of modernity in his ideas and theories: he was the true Father of Orthopaedics.

“BE FRUITFUL, AND MULTIPLY”: John Ball Brown

The American father of orthopaedics was John Ball Brown (1784–1862), who in 1838 founded the Boston Orthopaedic Institution (initially called the Orthopédique Infirmary), located two blocks from the Massachusetts General Hospital.

The son of a surgeon, Brown graduated from Brown University in 1806 and began his career in Dorchester before returning to Boston in 1812 [17]. A skilled physician, he gained fame rapidly and became a reference point for the entire medical community of the city.

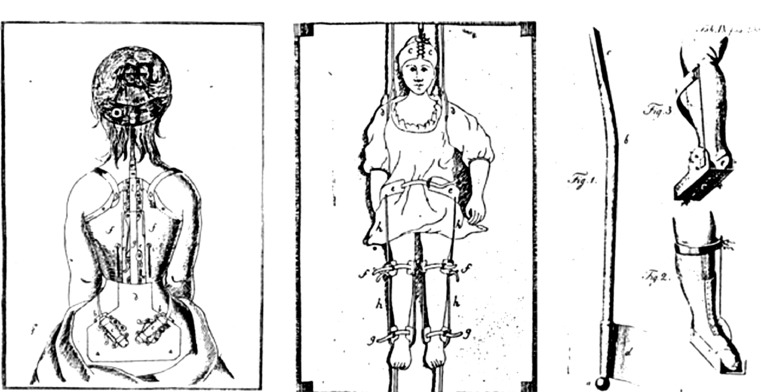

In 1837, he lost his elder son to spinal disease, and his younger son was afflicted by a severe spinal deformity. In 1838, pushed by the concern for the lack of medical focus on skeletal deformity, Dr. Brown devoted himself to the still new field of orthopaedic surgery; in 1839 he performed the first New England operation for the cure of clubfoot by the subcutaneous section of the contracted tendons [18], apparently the first tenotomy in the United States (Fig. 4). In the same period he performed a multitude of surgical procedures to treat distortion of the neck, spine and limbs, with patients coming from all over the United States to submit to his unique care.

“Having lost my eldest son […] by inflammation of the great spinal cord, and having now my second son confined to his bed by a lateral curvature of the spine, my attention has been forcibly drawn to the study and treatment of spinal disease generally, and to the correction of other deformities of the human body, such as distortion of the limbs, club feet, etc. etc.”

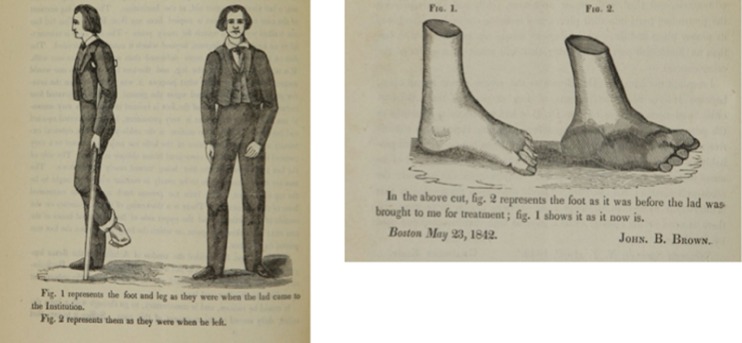

Fig. 4.

Drawings depicting a patient of Dr. John Ball Brown, before and after the treatment to correct club foot [23]

Orthopaedic surgery as a medical specialty began in the United States with John Ball Brown [19].

In 1845, the Boston Orthopaedic Institution had an outpatient infirmary and about 60 in-patient beds; inside the hospital, the best techniques and devices from Europe were used to treat the sick and, as at Venel’s hospital, treatment was mostly by braces, traction and daily manipulations, but not only that: Brown was a great defender of the peculiarity and importance of orthopaedic surgery.

In his own words: “[…] deformities of the human frame cannot be conveniently and judiciously treated except in a hospital or institution expressly devoted to this object. It is not for the interest of any general practitioner of medicine and surgery to be at the expense of furnishing himself with the variety of apparatus (some of which is very expensive) required in treating these deformities” [20].

John Ball Brown’s legacy was left directly to his son, Buckminster Brown (1819–1891) who, despite being affected by scoliosis, continued his father’s work with the same devotion and success. He was the first surgeon in the United States to entirely devote his practice to orthopaedics and he was also responsible for the foundation of an Orthopaedic Ward at the House of Good Samaritan in Boston (1861). He died in 1891 and his $40,000 donation to Harvard University was used to establish the “John Ball and Buckminster Brown Professorship of Orthopaedic Surgery” [21], a prestigious chair that still exists today.

Conclusions

Paying tribute to the most talented minds in medical history is a way of putting medical conquests into perspective and understanding the basics of current clinical practice. The aforementioned individuals contributed greatly to the establishment and development of orthopaedics in Europe and the United States. They were “stage setters” and they were the first to understand that musculoskeletal medicine needed its own recognition and a dedicated approach to provide the best care for patients. Venel and Brown were the founders of independent institutions where they provided both conservative and surgical management of common orthopaedic conditions. Their commitment was so strong and their ideals so great that their fame spread throughout Europe and the United States, and made a real contribution to the making of the history of our discipline. Their deeds were soon emulated, which led to the flourishing of orthopaedics. As we have seen, at the beginning our discipline mostly focused on the correction of children's deformities, but it took just a few decades to increase the range of conditions treated and procedures performed, becoming what we know today. Understanding the origins of our practice is a way of reinforcing our belief that a lot has been done but a lot still needs to be discovered. This concept was masterly expressed by the great English poet, Alfred Tennyson, in his masterpiece poem, Ulysses: “Tho’ much is taken, much abides” [22]. This should be the motto of any good surgeon and researcher, who should be aware that the experience and conquests of the past are just the foundation for future progress.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Liliana Draghetti (Donazione Putti, Biblioteche Scientifiche, Rizzoli Orthopaedic Institute) and Keith Smith (Task Force, Rizzoli Orthopaedic Institute) for their help.

References

- 1.Di Matteo B, Tarabella V, Filardo G, Viganò A, Tomba P, Marcacci M (2013) Thomas Annandale: the first meniscus repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013 Apr 11. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Donati D, Zolezzi C, Tomba P, Viganò A. Bone grafting: historical and conceptual review, starting with an old manuscript by Vittorio Putti. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(1):19–25. doi: 10.1080/17453670610013376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohler R. Nicolas Andry de Bois-Regard (Lyon 1658-Paris 1742): the inventor of the word ‘orthopaedics’ and the father of parasitology. J Child Orthop. 2010;4:349–355. doi: 10.1007/s11832-010-0255-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peltier LF. Nicolas Andry. The designer of orthopedic iconography. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;200:54–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonola A. Ricerche sulla Vita, le Opere ed il Ritratto di Nicolas Andry. La Chirurgia degli Organi in Movimento. 1937;22:385–399. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andry N (1700) De la génération des vers dans le corps de l’homme. De la nature & des espèces de cette maladie, de ses effets, de ses signes, de ses prognostics: Des moyens de s’en préserver, des remèdes pour la guérir. Paris, Chez Laurent d’Houry, 1700, 1st ed.

- 7.Andry N (1741) L‘orthopédie ou l’art de prevenir et de corriger dans les enfants les difformités du corps. A Paris, chez la Veuve Alix et chez Lambert et Durand, 1st ed.

- 8.Burrows HJ. Leonardo da Vinci and Nicholas Andry on Posture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1952;34-B(4):541–544. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.34B4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pope A (1735) Moral Essays, Epis 1

- 10.Peltier LF (1994) Ortopedia. Storia e Iconografia. Roma, CIC Ed, pp 23–25

- 11.Venel, JA (1778) Précis d’instruction pour les sages-femmes. Yverdon

- 12.Böni TH, RÜttimann B, Dvorak J, Sandler ABS (1994) Historical perspectives Jean-André Venel. Spine 19;17:2007–2011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Venel JA (1789) Description d’une nouvelle machine hydraulique, inventée et exécutée à Orbe. Historie et mémoires de la Société des sciences physiques de Lausanne 2:81–88

- 14.Venel JA (1769) Sur la meilleure construction des poeles et cheminées. Mémoires et observations recueillies par la Société oeconomique de Berne 1:105–172

- 15.Venel JA (1769) Sur la construction des fourneaux de chimie. Mémoires et observationns recueillies par la Société oeconomique de Berne 2:5–78

- 16.Venel JA (1769) Nouveaux secours pour les corps arretés dans l’oesophage, ou description de quelques instruments plus propres qu’aucun des anciens moyens à retirer ces corps par la bouche, inventé par M. Venel. Lausanne, F. Grasset (ed)

- 17.Massachusetts Medical Society (1862) Obituary: John Ball Brown. Medical Communications of Massachusetts Medical Society 10:158–159

- 18. No Author Given (1862) Obituary. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 66:362–364

- 19.Cohen J (1958) The Boston Orthopedic Institution. J Bone Joint Surg. 40/A:1176–1178 [PubMed]

- 20.Rutkow IM (1992) The history of surgery in the United States 1775–1900. S. Francisco, Norman Publ, pp 148–149

- 21.Bick EM. American Orthopedic Surgery: the first 200 years. N Y State J Med. 1976;76:294–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tennyson A (1842) Poems: Ulysess

- 23.Brown JB (1844) Reports of cases in the Boston Orthopedic Institution: or Hospital for the Cure of Deformities of the Human Frame. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal