Abstract

Introduction

We investigated the predictive and prognostic effects of VeriStrat®, a serum or plasma based assay, on response and survival in a subset of patients enrolled on the NCIC Clinical Trials Group (CTG) BR.21 phase III trial of erlotinib versus placebo in previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients.

Methods

Pretreatment plasma samples were available for 441 of 731 enrolled patients and were provided as anonymized aliquots to Biodesix. The VeriStrat test was performed in a CLIA-accredited laboratory at Biodesix, Inc. Results (Good, Poor) were returned to NCIC CTG, who performed all statistical analyses.

Results

VeriStrat testing was successful in 436 samples (98.9%), with 61% classified as Good. VeriStrat was prognostic for overall survival in both erlotinib-treated patients and those on placebo, independent of clinical covariates. For VeriStrat Good patients, the median survival was 10.5 months on erlotinib vs. 6.6 months for placebo (HR 0.63, 95% C.I. 0.47–0.85, P=0.002). For VeriStrat Poor patients, the median survival was 4 months for patients receiving erlotinib, and 3.1 months for placebo (HR: 0.77, 95% C.I. 0.55–1.06, P=0.11). VeriStrat was predictive for objective response (P =0.002), but was not able to predict for differential survival benefit from erlotinib (interaction p-value 0.48). Similar results were found for progression-free survival (PFS).

Conclusion

We were able to confirm that VeriStrat is predictive of objective response to erlotinib. VeriStrat is prognostic for both OS and PFS, independent of clinical features, but is not predictive of differential survival benefit vs. placebo.

Keywords: erlotinib, proteomics, metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, biomarkers

Introduction

BR.21 was a randomized placebo-controlled study of erlotinib in previously treated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The overall response rate was 8.9% in the erlotinib arm compared to <1% for placebo, and both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were prolonged by erlotinib.1 Correlative studies performed in patients with available tissue showed that EGFR protein expression, the presence of activating EGFR mutations and high EGFR copy number were predictive of response. EGFR mutations were prognostic for OS, but were not predictive, while increased EGFR copy number was both prognostic and predictive for OS benefit.2,3 Tumor tissue was not available in all patients, highlighting the need for less invasive predictive tests such as serum or plasma biomarkers. A recent exploratory study on plasma samples from BR.21 reported amphiregulin as a prognostic marker and transforming growth factor-α as a biomarker predictive of OS benefit from erlotinib4; these observations remain to be validated in prospective clinical trials.

VeriStrat is a commercially-available serum- or plasma-based test utilizing matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry methods. Testing is conducted by Biodesix, Inc in their CLIA-accredited laboratory. It was developed using a training set of pretreatment serum samples from patients who experienced long-term stable disease or early progression on gefitinib therapy.5 Mass spectra (MS) from these patients’ serum samples were used to define eight MS features (i.e. peaks), differentiating these two outcome groups. An algorithm utilizing these features and based on a k-nearest neighbors (KNN) classification scheme was created and its parameters were optimized using additional spectra from the training cohort. The current commercial test uses a fixed set of parameters established during the development phase. VeriStrat assigns each spectrum a binary classification of Good or Poor. Validation studies were performed in a blinded fashion using multiple single-arm cohorts of patients undergoing EGFR TKI therapy. Two independent cohorts of patients who were treated with gefitinib or erlotinib confirmed that patients classified as Good had better outcomes than patients classified as Poor (HR of death 0.47, P=0.009 and HR of death 0.33, P=0.0007).5 In other control cohorts, VeriStrat status did not correlate significantly with clinical outcome following chemotherapy (HR 0.74, P=0.42 and HR 0.81, P=0.54) or in the post-surgery setting (HR 0.90, P=0.79) 5. Based on these results, it was postulated that VeriStrat might be a predictive marker specifically for EGFR TKI therapy.

The primary goal of the current study was to test VeriStrat’s ability to predict response and survival benefit (PFS and OS) from erlotinib, using pretreatment plasma samples from BR.21.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Plasma Samples

In BR.21, 731 patients were randomized (2:1 ratio) to receive erlotinib or placebo. The clinical trial database resides at NCIC CTG. Full details of the methodology have been published previously1. Blood samples were collected from consenting patients for pharmacokinetic assays and for banking and stored at the Tumour Tissue Repository of the NCIC CTG, in Kingston, Ontario. Patients provided separate written consent for this optional tissue banking. Baseline pretreatment samples from consenting patients were anonymized using a unique ID, aliquoted, and provided to Dr. David Carbone for analyses. No clinical data were sent. The Research Ethics Board at Vanderbilt University approved this study.

VeriStrat Analysis

VeriStrat analysis was conducted on 441 available plasma samples by Biodesix (Broomfield, CO). Samples were thawed on wet ice and aliquots diluted 1:10 in HPLC-grade water (Burdick & Jackson, Muskegon, MI) then combined with an equal volume of sinapinic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) solution (25 mg/ml sinapinic acid prepared in 50% acetonitrile/0.1% [Burdick & Jackson, Muskegon, MI] trifluoroacetic acid [Sigma,St. Louis, MO]). Each sample-matrix mixture was spotted in triplicate at randomly assigned positions on polished stainless steel MALDI plates (BrukerDaltonics, Bremen, Germany). Positive ion mass spectra for all samples and replicates were acquired in linear mode using the BrukerAutoflex III mass spectrometer. Averaged spectra, consisting of 2000 independent spectrum acquisitions, from each sample replicate were used for processing and classification. Spectral processing included background (BG) and noise estimation, BG subtraction, normalization to partial ion current and alignment. The classification algorithm, a KNN classifier based on eight distinct m/z features,5 was applied to the averaged, processed spectra. A VeriStrat label of Good or Poor was produced for each sample when all replicates from a sample gave the same classification. When replicates from a sample gave discordant classifications an indeterminate label was assigned. Results were sent to NCIC CTG where they were merged with the clinical trial database.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis plan was agreed prior to any analyses being conducted. Exploratory analyses were performed to characterize the relationship between VeriStrat status and baseline characteristics and outcomes. Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess the association between categorical variables; the Kaplan-Meier product limit method and the log-rank test were used to estimate and compare the distributions of time to event outcomes. A Cox regression model with interaction terms included was used to verify VeriStrat’s prognostic and predictive effect on the primary endpoint of OS while adjusting for other baseline factors, including sex, age (≤60 vs. >60), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status (PS) (0,1 vs. 2,3), pathologic subtype (adenocarcinoma vs. squamous vs. others), response to prior therapy (CR/PR vs. PD vs. SD), number of prior regimens (1 vs. 2/3), prior platinum, EGFR expression by IHC (positive vs. negative vs. unknown), race (Asian vs. other), EGFR gene mutation status (exon 19 or 21 vs. not mutated + other mutation vs. unknown), time from diagnosis to randomization (<12 months vs. ≥ 12 months), weight loss (< 5% vs. ≥ 5%), smoking status (non-smoker vs. ever smoked vs. unknown) and EGFR FISH status: (high copy/amplified [FISH+] vs. low copy [FISH−] vs. unknown). Prognostic analyses were performed on patients enrolled to the placebo arm only. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All reported P values are two-sided and levels of significance taken to 0.05.

Results

VeriStrat

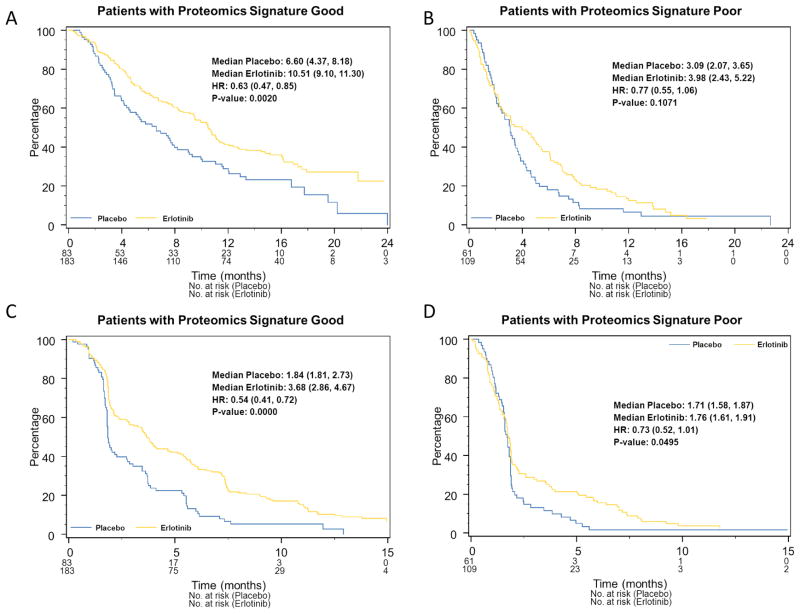

Of 441 plasma samples available, 436 (98.9%) could be classified as Good or Poor. Table S1 summarizes the baseline factors for patients with evaluable results. The evaluable cohort had significantly more male patients (P=0.03) and derived better OS benefit from erlotinib (HR: 0.67, 95%C.I.: 0.54–0.83, P=0.0003, Figure 1) compared to the non-evaluable cohort (HR: 0.93, 95%C.I. 0.73–1.22, P=0.61). In the Cox regression model the test of interaction was 0.06. The reason for the differential benefit is unclear.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots of OS for patients A) with or B) without available plasma.

Baseline characteristics for evaluable patients classified as Good and Poor are summarized in Table S2. Patients classified as Good were more likely to have characteristics usually associated with better prognosis: female sex (P=0.02), asian race (P=0.005), good PS (P<0.0001), adenocarcinoma (P<0.0001) and weight loss <5% (P<0.0001). There was no significant correlation between classification and smoking status or response to prior chemotherapy. Although there was a correlation between classification and EGFR IHC status, as in previous studies6,7 no significant correlations were found with EGFR or KRAS mutation status, or EGFR gene copy number. Although the differences were not significant most patients who had EGFR exon 19 or 21 mutations were in the Good cohort (71%) as were lifetime non-smokers (65%).

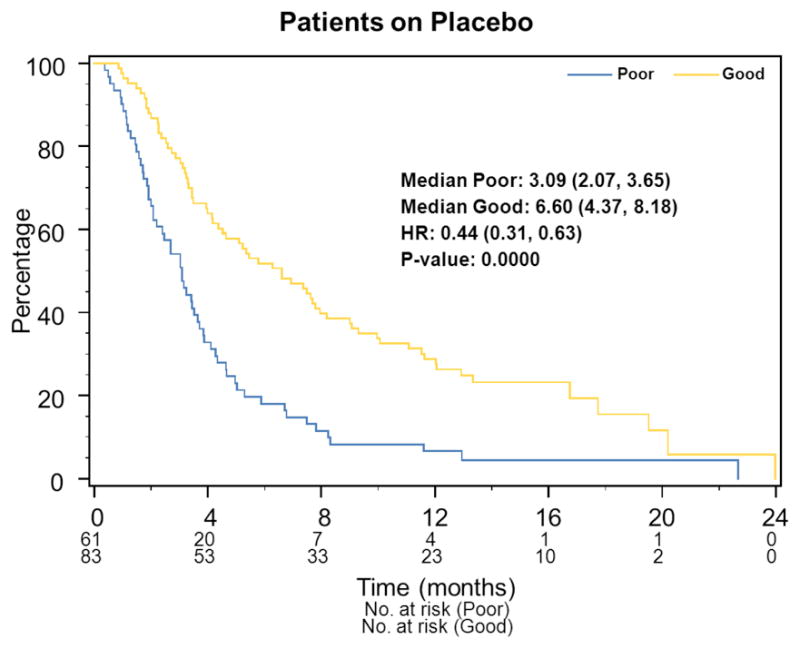

Prognostic Properties of VeriStrat

OS for the 144 placebo patients is shown in Figure 2. VeriStrat was prognostic with Good patients (median survival 6.6 months, 95% CI: 4.4–8.2) surviving significantly longer than Poor patients (3.1 months, 95%CI: 2.2–3.7; HR 0.44, 95% CI: 0.31–0.63, P<0.0001). VeriStrat remained prognostic (P=0.05) in multivariate analysis (Table 1). Similar results were obtained for PFS (data not shown); HR Good versus Poor 0.59 (95%CI: 0.42–0.83, P=0.0016) in both univariate and multivariate (P=0.001) analysis (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Prognostic Analysis: Kaplan-Meier plots of OS.

Table 1.

Multivariate Prognostic Analyses of OS and PFS for the Placebo Arm

| Variable | OS | PFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| VeriStrat | ||||

| Poor | 1 | 1 | ||

| Good | 0.67 (0.45–1.01) | 0.05 | 0.56 (0.40–0.80) | 0.001 |

| PS | ||||

| 0,1 | 1 | |||

| 2,3 | 1.77 (1.14–2.76) | 0.01 | ||

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 | |||

| Squamous | 1.71 (1.11–2.63) | 0.015 | ||

| Other | 0.80 (0.45–1.24) | 0.25 | ||

| Weight Loss | ||||

| Less than 5% | 1 | |||

| 5% or more | 2.03 (1.31–3.15) | 0.0015 | ||

| Unknown | 0.60 (0.23–1.56) | 0.29 | ||

| FISH | ||||

| FISH− | 1 | 1 | ||

| FISH+ | 2.23 (1.03–4.83) | 0.04 | 2.01 (1.04–2.23) | 0.04 |

| Unknown | 1.51 (0.84–2.70) | 0.17 | 1.58 (0.93–2.66) | 0.09 |

| Time from diagnosis to randomization | ||||

| ≤ 12 months | 1 | |||

| > 12 months | 0.50 (0.34–0.74) | 0.0005 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 | |||

| Male | 1.52 (1.04–2.23) | 0.03 | ||

Missing items indicate that a variable was not significant and so was not used in the analysis.

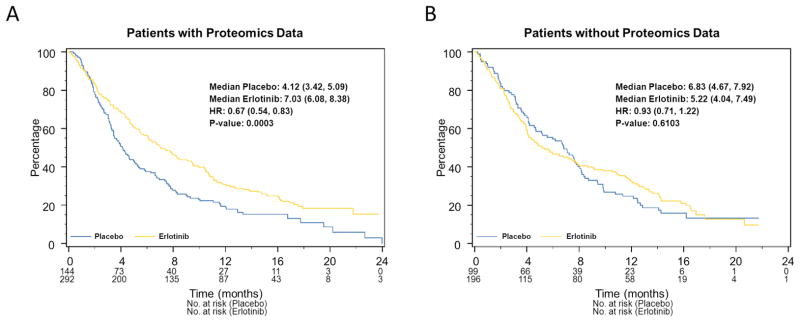

Predictive Properties of VeriStrat on Survival

The interaction term comparing relative benefit in the two cohorts was not significant (P=0.48), indicating that both the Good and Poor cohorts derived similar relative benefit from erlotinib. Median survival was 10.5 months for Good patients treated with erlotinib versus 6.6 months for those on placebo (HR 0.63, 95%CI 0.47–0.85; P=0.002) (Figures 3 A and B) while in the Poor cohort, the median survival for erlotinib was 3.98 months and 3.09 months for placebo (HR 0.77, 95%CI 0.55–1.06, P=0.11). Similar results were found in multivariate analyses (Table 2) adjusted for potential confounding factors and other predictive markers with a non-significant interaction test (P=0.50). In unplanned exploratory analyses EGFR copy number (FISH +) was predictive of erlotinib benefit (P=0.05).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier plots of OS by treatment arm for A) VeriStrat Good patients and B) VeriStrat Poor patients. Kaplan-Meier plots of PFS by treatment arm for C) VeriStrat Good patients and D) VeriStrat Poor patients

Table 2.

Multivariate Predictive Analyses of OS and PFS for the Patients with Evaluable Blood Samples

| Variable | OS | PFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Placebo | 1 | 1 | ||

| Erlotinib | 0.98 (0.51–1.90) | 0.96 | 1.40 (0.75–2.61) | 0.29 |

| VeriStrat | ||||

| ’Poor’ | 1 | 1 | ||

| ’Good’ | 0.52 (0.35–0.76) | <0.0006 | 0.71 (0.50–1.02) | 0.06 |

| Treatment x VeriStrat Interaction | 0.86 (0.55–1.34) | 0.50 | 0.77 (0.51–1.18) | 0.23 |

| PS | ||||

| 0,1 | 1 | |||

| 2,3 | 1.62 (1.27–2.06) | 0.0001 | ||

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Ever Smoker | 1 | 1 | ||

| Never Smoker | 0.59 (0.44–0.78) | 0.0003 | 0.72 (0.56–0.93) | 0.01 |

| Unknown | 0.73 (0.45–1.17) | 0.19 | 0.82 (0.53–1.28) | 0.38 |

| Weight Loss | ||||

| Less than 5% | 1 | 1 | ||

| 5% or more | 1.63 (1.27–2.09) | 0.0001 | 1.44 (1.14–1.82) | 0.0025 |

| Unknown | 0.59 (0.31–1.13) | 0.11 | 0.90 (0.52–1.55) | 0.70 |

| FISH | ||||

| FISH− | 1 | 1 | ||

| FISH+ | 1.64 (0.82–3.28) | 0.16 | 2.48 (1.27–4.83) | 0.008 |

| Unknown | 1.30 (0.75–2.23) | 0.35 | 1.70 (1.01–2.88) | 0.047 |

| Treatment x FISH+ | 0.39 (0.15–0.99) | 0.05 | 0.22 (0.09–0.54) | 0.0009 |

| Treatment x FISH unknown | 0.75 (0.38–1.47) | 0.40 | 0.51 (0.27–0.96) | 0.04 |

| Time from Diagnosis to Randomization | ||||

| ≤ 12 months | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 12 months | 0.69 (0.55–0.86) | 0.0009 | 0.82 (0.67–1.00) | 0.05 |

| Prior Regimen | ||||

| 1 | 1 | |||

| 2+ | 1.25 (1.01–1.55) | 0.04 | ||

Missing items indicate that a variable was not significant and so was not used in the analysis.

Similar results were seen for PFS (Figures 3C and 3D). Both Good and Poor patients had significant PFS benefit from treatment (P=0.0000 and 0.05, respectively, interaction P=0.36). In multivariate adjusted analyses, the interaction p-value again was not significant (Table 2).

Predictive Properties of VeriStrat for Objective Response

Response data for patients on the erlotinib arm8 are summarized in Table 3. Of 252 erlotinib-treated patients evaluable for response, 157 (62%) were classified as Good and 95 (38%) as Poor. Good patients had a significantly higher response rate than Poor patients (11.5% vs. 1.1%, P=0.002), with a Good classification remaining independently significantly correlated with response after adjustment for potential confounding factors (Table S3).

Table 3.

Objective Responses in Erlotinib-treated patients by VeriStrat Status.

| VeriStrat Good | VeriStrat Poor | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients Evaluable for Response | 157 | 95 | 252 |

| Patients not Evaluable for Response | 26 | 14 | 40 |

| PD/SD (%) | 139 (89%) | 94 (99%) | 233 (92%) |

| PR/CR (%) | 18 (11%) | 1 (1%) | 19 (8%) |

Exploratory Subgroup Analyses

In analyses of patients without detected activating EGFR mutations (exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R) and patients without adenocarcinoma histology, there was no significant interaction, indicating no evidence of differential benefit for either subgroup (P=0.51 and P=0.73 respectively). The median OS for Good patients was 10.5 vs. 6.3 months (HR 0.63 in patients without detected activating EGFR mutation, P=0.004) and 10.5 vs.5.8 months, (HR 0.60 for non-adenocarcinoma P=0.02) respectively, and for Poor patients, 4.0 vs.3.1 months, (HR 0.78 in patients without detected activating EGFR mutation P=0.13) and 4.9 vs. 3.1 (HR 0.71 non-adenocarcinoma, P=0.11).

Discussion

Biomarker-based selection of patients for specific targeted therapies is becoming a standard of care9,10. One example of this is patients whose tumors carry activating EGFR mutations..11,12 The Iressa Pan-Asia Study (IPASS) trial (gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel as first-line treatment for pulmonary adenocarcinoma among an Asian population of never-smokers or former light smokers) clearly demonstrated the superiority of gefitinib versus chemotherapy in terms of PFS and response rate (although not OS), for those with EGFR mutation-positive tumors13,14. The results of trials performed after at least second-line treatment also confirmed the predictive effect of EGFR mutations on tumor response and PFS; however, the predictive effect of mutations on OS remains unclear, as patients with EGFR mutant tumors appear to survive longer regardless of therapy. While this is usually attributed to the effects of post-progression crossover to TKI treatment, trials of unselected patients have demonstrated survival benefit in patients without such mutations15. An analysis of BR.21 showed that EGFR mutations and high EGFR copy number are predictive of response to erlotinib, but mutation status was not predictive of OS benefit compared to patients with wild-type EGFR tumors, although the number of patients with mutations probably was too low to demonstrate significant quantitative interaction3. The Iressa Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Trial Evaluating Response and Survival against Taxotere (INTEREST), a randomized study comparing second-line treatment with docetaxel or gefitinib, also showed the predictive role of EGFR mutations in response and PFS to gefitinib, while no measured biomarker was predictive of differential survival benefit10,16. Interestingly, the Sequential Tarceva in Unresectable NSCLC (SATURN) trial of maintenance erlotinib showed statistically significant OS benefit only in patients without EGFR mutations17, and in BR.19, where unselected patients were randomized to gefitinib vs. placebo as post-operative adjuvant therapy, there was no survival benefit in the overall study population, nor in patients with EGFR mutated tumors18.

Activating EGFR mutations are present in approximately 30–40% of Asian patients, but only 5–15% in Caucasians19,20. While large scale mutation screening is feasible21, sample collection and successful mutation analysis in most large multisite clinical trials typically have been low, (20–30%). This may be due to many factors including scanty tissue from cytology diagnostic slides, tissue-quality requirements for the biomarker assay, and the capacity and infrastructure of the investigational site22. In recent publications, it has been highlighted that while DNA sequence abnormalities may appear to be very readily and reliably measured, in practice the observed discordance of mutation status assessment is highly dependent on sample quality and the method of analysis, and can reach 30%. This may affect the outcome of treatment23. Thus, the presence of EGFR mutations, while now widely accepted as the basis for choosing an EGFR-TKI for front-line therapy of advanced NSCLC, does not identify the entire population of NSCLC patients who may benefit from these drugs. Especially useful would be biomarkers that that can be measured using samples obtained by non-invasive procedures in every patient.

As a blood-based test, VeriStrat, is reproducible, readily available and has the potential to overcome the difficulties of obtaining fresh biopsy tissue from patients. In published studies using samples from patients not enrolled in randomized controlled trials, it was suggested that VeriStrat might be predictive of EGFR inhibitor benefit even in a population of smokers and in those with squamous carcinoma.5 Further studies in other tumor types also reported different survival outcomes in VeriStrat Good and Poor subsets that was independent of the specific anti EGFR agents used.7 In squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN), VeriStrat Good designation was associated with longer survival in patients treated with gefitinib (HR Good vs. Poor 0.41, P=0.007) and in studies of patients treated with erlotinib/bevacizumab (HR 0.2, P=0.02), and cetuximab (HR 0.26, P=0.06). The patients in these analyses were not part of randomized trials with control arms that did not include EGFR therapy; however, two chemotherapy-only cohorts of lung cancer patients5, a chemotherapy-only cohort of SCCHN patients7, and a surgery-only cohort of lung cancer patients5 showed no statistically significant survival difference when classified by the VeriStrat test. In another cohort study of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients treated with cetuximab, PFS was significantly longer for Good compared to Poor patients (HR 0.51, P=0.0065).7 In a study of NSCLC patients treated second-line with a combination of erlotinib and bevacizumab, patients classified as Poor were shown to have extremely poor OS and PFS24 compared to those classified as Good (HR 0.14, P=0.007 and HR 0.045, P=0.0003 for OS and PFS, respectively). Similar results were obtained in a first-line study of the same combination of targeted treatments in non-squamous NSCLC, which reported a median PFS of 16.5 weeks in Good patients and 9.3 weeks in Poor patients and median OS of 79.1 weeks in Good patients and 12.5 weeks in Poor patients25. A study of NSCLC patients treated with first-line erlotinib and sorafenib found a HR of 0.30 (95% CI 0.12–0.74; P=0.009) for OS and 0.40 (95% CI 0.17–0.94, P=0.035) for PFS between Good and Poor patients.26

Because of the absence of randomization to control arms that did not include EGFR therapy in the above studies, it was not possible assess whether the VeriStrat test identified two cohorts of patients with different prognoses or whether it truly was predictive of better outcome from EGFR inhibitor therapy. In all three of the chemotherapy-only and surgical studies, VeriStrat Good patients experienced longer survival than Poor patients. Although the differences in survival were not significant, these studies may have provided the first hint that VeriStrat might be a prognostic test.

Our study evaluated both the prognostic and predictive value of VeriStrat. Out of 731 patients enrolled on BR.21, plasma samples from 441 were available for testing and it was possible to classify 99% of patients into Good and Poor cohorts. We were able to confirm that VeriStrat was predictive of response. However, for both OS and PFS, VeriStrat was prognostic, but was not predictive of differential benefit from erlotinib. In exploratory analyses, although significant correlation was detected between VeriStrat and EGFR protein expression determined by immunohistochemistry, no significant correlations were found with other measured biomarkers, including EGFR or KRAS mutation status, and EGFR FISH status, confirming results from previous studies.6,7

There are several limitations to our study. Although plasma collection was planned prospectively in the original clinical trial, this assay and analyses were not. While sample size estimations prior to our analyses suggested sufficient power to test the hypothesis, the sample size of the clinical trial was based on clinical outcomes, and not all patients consented to the storage of plasma, leading to a non-random subset of patients in this study. Indeed, there were differences in baseline clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with and without plasma samples,4 a common problem of retrospective biomarker studies on subsets of the trial population.27

Although our results confirm a predictive effect of VeriStrat for response, they do not confirm a predictive effect for Veristrat on OS or PFS. VeriStrat did appear to identify a subset of previously treated patients that experienced a survival benefit that may be considered more clinically meaningful than that seen in VeriStrat poor patients where survival was short. Alternatives to erlotinib may be considered for these patients. More information should become available from the Randomized Proteomic Stratified Phase III Study of Second Line erlotinib versus Chemotherapy in Patients with Inoperable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (PROSE) currently accruing, which will compare erlotinib with chemotherapy in patient cohorts stratified according to VeriStrat classification.

The nature, origin, and potential direct biological significance of the detected protein biomarkers is as yet not completely clear. As biomarker studies developing classifiers from large protein or RNA expression datasets essentially are correlative in nature, conclusions about cause and effect between the measured biomarkers and the measured outcomes frequently are impossible. Despite these considerations, efforts have been made to identify the proteins constituting the measured features. Several of the peaks are isoforms of serum amyloid A, but several remain to be identified. However, the Poor classification has not yet been seen in non-cancer patients, including our studies of inflammatory diseases associated with high SAA levels, such as rheumatoid arthritis or COPD. As the VeriStrat Poor classification has now been identified in many epithelial cancer types, including breast, renal, colorectal, melanoma, upper GI, and head and neck, but not in healthy patients, and since the mechanism of MALDI mass spectrometry makes it easiest to detect high to mid-range abundance proteins, it is quite likely that VeriStrat is detecting a tumor-host response to the presence of the cancer.

Recently, in exploratory hypothesis generating analyses, the EGFR ligand TGF-alpha was shown to be predictive of benefit from erlotinib vs. placebo in this same patient population.4 High baseline TGF-alpha (present ~10 percent of study patients) predicted lack of benefit from erlotinib compared with low TGF-alpha (TGF-alpha low, OS HR 0.66; 95% CI, 0.54–0.81; P=.0001; high, OS HR 1.32; 95% CI, 0.73–2.39; P=0.36; interaction P=0.04). Baseline TGF-alpha was not prognostic or predictive for PFS. In the same study, amphiregulin, another EGFR ligand, was found to be prognostic, but not predictive of a differential survival benefit from erlotinib. However, this study did not have separate training and testing cohorts, and thus the results require independent confirmation.

In summary, VeriStrat is able to predict response to erlotinib and is a prognostic biomarker in previously treated patients with advanced NSCLC. Further studies are required to define the clinical utility of VeriStrat and other blood-based biomarkers in defining the appropriate patient population for therapy with erlotinib and other EGFR based therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NCI SPORE P50-90949 (DPC), SPECS U01 CA114771 (DPC), BioDesix, Inc.

References

- 1.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer - molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu CQ, da Cunha Santos G, Ding K, et al. Role of KRAS and EGFR as biomarkers of response to erlotinib in National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR. 21. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4268–4275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Addison CL, Ding K, Zhao H, et al. Plasma transforming growth factor alpha and amphiregulin protein levels in NCIC Clinical Trials Group BR. 21. Journal of Clinical Oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:5247–5256. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taguchi F, Solomon B, Gregorc V, et al. Mass spectrometry to classify non-small-cell lung cancer patients for clinical outcome after treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a multicohort cross-institutional study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:838–846. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amann JM, Lee JW, Roder H, et al. Genetic and proteomic features associated with survival after treatment with erlotinib in first-line therapy of non-small cell lung cancer in Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 3503. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;5:169–178. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c8cbd9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung CH, Seeley EH, Roder H, et al. Detection of tumor epidermal growth factor receptor pathway dependence by serum mass spectrometry in cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:358–365. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douillard JY. Targeting the target: a step forward for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:104–105. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70390-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douillard JY, Shepherd FA, Hirsh V, et al. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib and docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer: data from the randomized phase III INTEREST trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;28:744–752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuoka MWY, Thongprasert S, et al. Biomarker analyses from a phase III randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib (G) versus carboplatin/paclitaxel (C/P) in clinically selected patients (pts) with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in Asia (IPASS) J Clin Oncol. 2009:27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reck M. A major step towards individualized therapy of lung cancer with gefitinib: the IPASS trial and beyond. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2010;10:955–965. doi: 10.1586/era.10.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark GM, Zborowski DM, Santabarbara P, et al. Smoking history and epidermal growth factor receptor expression as predictors of survival benefit from erlotinib for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer in the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group study BR. 21. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;7:389–394. doi: 10.3816/clc.2006.n.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): a randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1809–1818. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, et al. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:521–529. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goss GDLI, Tsao MS, O’Callaghan CJ, Ding K, Masters GA, Gandara DR, Jett JR, Edelman MJ, Shepherd FA. A phase III randomized, double blind- placebo-controlled trial of the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor gefitinib in completely resected stage 1B-IIIA non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): NCIC CTG BR.19. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yatabe Y, Mitsudomi T. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancers. Pathol Int. 2007;57:233–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saijo N, Takeuchi M, Kunitoh H. Reasons for response differences seen in the V15–32, INTEREST and IPASS trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:287–294. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, et al. Screening for Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations in Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirsch FR, Bunn PA., Jr EGFR testing in lung cancer is ready for prime time. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:432–433. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70110-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gow CH, Chang YL, Hsu YC, et al. Comparison of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations between primary and corresponding metastatic tumors in tyrosine kinase inhibitor-naive non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:696–702. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carbone DP, Salmon JS, Billheimer D, et al. VeriStrat((R)) classifier for survival and time to progression in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with erlotinib and bevacizumab. Lung Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akerley W, Rich NT, Egbert L, Harker WG, Van Duren T, Smit J, Hoffman JM. Bevacizumab/erlotinib (BEER) as first-line treatment for untreated advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl):abstract 318008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smit EFRH, Grigorieva J, Roder J, Lind JSW, Dingemans AC, Groen JHM. The proteomic classifier VeriStrat identifies advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients gaining clinical benefit from treatment with first line sorafenib and erlotinib. 22nd EORTC-NCI-AACR symposium on “Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics”; Berlin, Germany. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon RM, Paik S, Hayes DF. Use of archived specimens in evaluation of prognostic and predictive biomarkers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1446–1452. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]