Abstract

Objective

Human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly HPV16, is a causative agent for 25% of head and neck squamous cell cancer, including laryngeal squamous cell cancer (LSCC). HPV positive (HPV+ve) patients, particularly oropharyngeal SCC, have improved prognosis. For LSCC, this remains to be established. The goal was to determine stage and survival outcomes in LSCC in the context of HPV infection.

Study Design

Historical cohort study.

Setting

Primary care academic health system.

Subjects and Methods

In 79 primary LSCC, HPV was determined using real-time quantitative PCR. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to test association of HPV+ve with 21 risk factors including race, stage, gender, age, smoking, alcohol, treatment, and health insurance. Kaplan-Meier and log rank test were used to study the association of HPV and LSCC survival outcome.

Results

HPV16 was detected in 27% LSCC. There was a trend towards higher HPV prevalence in Caucasian American (CA, 33%) vs African American (AA, 16%) (p=0.058). HPV was significantly associated with gender (p=0.016) and insurance type (p=0.001). HPV+ve LSCC had a slightly longer survival than HPV-negative (HPV−ve) patients, but the differences were not significant. There was no association with HPV and other risk factors including stage (early vs late).

Conclusion

We found high prevalence of HPV in males and lower prevalence of HPV infection in AA compared to CA. A slightly better survival for HPV+ve LSCC versus HPV−ve was noted but was not significant. Larger multi ethnic LSCC cohorts are needed to more clearly delineate HPV related survival across ethnicities.

INTRODUCTION

Laryngeal squamous cell cancer (LSCC), the largest subgroup of head and neck cancers share common risk factors to include smoking, and alcohol consumption. The human papilloma virus (HPV) is a causative agent for some HNSCC1, 2 and an independent risk factor for oropharyngeal HNSCC.3-5 A systematic review of 5046 patients with HNSCC reported an overall prevalence of HPV infection of 25.9% and concurs with a more recent meta-analysis of 5681 HNSCC.6 The prevalence of HPV infection was significantly higher among patients with oropharyngeal SCC (35.6%) than among those with oral (23.5%) or laryngeal (24.0%) SCC.7 Approximately 95% of these HNSCC subgroups contain high-risk HPV type 16 (HPV16) genomic DNA sequences.8 Its contribution to neoplastic progression is predominantly through the action of the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7.9 Expression of these proteins is sufficient for the immortalization of primary human epithelial cells and induction of histologic atypia characteristic of pre-invasive HPV-associated squamous intraepithelial lesions.10

The contribution of HPV genotypes to HNSCC pathogenesis is of clinical significance. HPV positive (HPV+ve) patients particularly those with oropharyngeal cancer, have improved prognosis. Patients whose tumors test positive for HPV have at least half the risk ofdeath from HNSCC and respond better to treatment than those who test negative.3, 11 This includes selection of patients for organ preservation therapy, which may be more successful in patients with HPV+ve HNSCC.12

Also, a recent study found that poorer survival outcomes for African American (AA) versus Caucasian American (CA) with oropharyngeal tumors was attributable to racial differences in the prevalence of HPV+ve tumors. HPV positivity was higher in CA (34%) as compared to 4% in AA and HPV negative (HPV−ve) AA and CA patients had similar survival outcomes.13 Therefore, the therapeutic implications of an HPV+ve diagnosis are an important area of investigation with mounting evidence for future clinical trials designed specifically for patients with HPV+ve or HPV−ve HNSCC stratified according to HPV status.3 For LSCC, survival outcomes based on overall prevalence of HPV, especially race-based prevalence remain to be established. The goal of this study was to evaluate stage at diagnosis and survival outcomes in LSCC in the context of HPV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cohort

The retrospective study cohort of 79 primary LSCC was examined for a set of 21 variables to include 8 histopathology factors14: tumor grade(well, moderate, poorly differentiated), lymphocytic response (continuous rim/ patchy infiltrate/ absent), desmoplastic response (prominent & diffuse/ patchy & irregular/ focal/ absent), pattern of invasion (host/tumor interface with pushing cohesive borders (mode 1)/ solid cords (mode 2)/ thin irregular cords(mode 3)/ single cells(mode 4)), vascular invasion (identified /absent), perineural invasion (identified /absent), reversed mitotic index (<5 mitosis per 10 high power fields (HPF)/ >5 mitosis per10 HPF) and necrosis (extensive/minimal/absent); demographics ( 5 variables-race [as self reported], gender, age, marital status and highest education), clinical factors (3 variables – comorbidity, pneumonia and family history of cancer), smoking, alcohol, stage, HPV status, and health insurance type. Overall comorbidity was determined using the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27 (ACE-27) index for cancer patients15. The ACE-27 categorizes specific diseases into one of three grades: grade 1 (mild), grade 2 (moderate), and grade 3 (severe), based on organ decompensation and prognostic impact. An overall comorbidity score (none - 0; mild - 1; moderate - 2; or severe - 3) is assigned based on the highest ranked/graded single ailment16. If two or more moderate grade ailments occur in a case, the overall comorbidity score is designated as severe

Access to care for this cohort is defined as the availability of health care insurance at the time of diagnosis. Health insurance payors included Blue Cross, Medicare, Medicaid, Health Alliance Plan (HAP, a Health Maintenance Organization [HMO]), and other non-HAP HMO’s. These patients were categorized into four treatment groups of surgery alone (no radiation or chemotherapy - No R/C), radiation only (R), radiation plus chemotherapy (R+C), and chemotherapy only (C).

This study was approved by the Henry Ford Health System Institutional Review Board.

DNA Extraction

Whole 5 micron tissue sections or microdissected LSCC lesions and adjacent normal when present were processed for DNA extraction as previously described.17

HPV16 Detection by Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

Tumor HPV DNA concentrations were measured using a real-time quantitative PCR system. Real-time PCR reactions were set up in a reaction volume of 20 ul using the TaqMan Universal Master Mix II with UNG (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Specific primers and probes were designed to amplify a housekeeping gene, ß-globin18 (to standardize the input DNA), and the E6 region of HPV16.19 The primers and probes used were as follows: ß-globin: forward 5′-GTGCACCTGACTCCTGAGGAGA-3′, reverse 5′-CCTTGATACCAACCTGCCCAG-3′, 6FAM-5′- AAGGTGAACGTGGATGAAGTTGGTGG-3′-TAMRA; HPV16 E6 region: forward 5′- GAGAACTGCAATGTTTCAGGACC-3′, reverse 5′- TGTATAGTTGTTTGCAGCTCTGTGC-3′, 6FAM-5′- CAGGAGCGACCCAGAAAGTTACCACAGTT-3′-TAMRA. DNA amplifications were carried out in a 96-well reaction plate format in a PE Applied Biosystems 7500HT Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). HPV viral copy number was determined using the CaSki cell line genomic DNA reported to contain an integrated human papillomavirus type 16 genome (about 600 copies per cell). Multiple water blanks and HPV16 positive controls (HPV+ve HNSCC specimens) were included in every run. Both the HPV and ß-globin PCR reactions were carried out in duplicate.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR Data Analysis

CaSki cell line (American Type Culture Collection-ATCC, Manassas, VA) genomic DNA is known to have 600 copies/genome equivalent (6.6 pg of DNA/genome). Standard curves were developed for HPV16 viral copy number using serial dilutions of 50 ng, 5 ng, 0.5 ng, 0.05 ng, and 0.005 ng of DNA. Using the same serial dilutions, standard curves were also developed for the ß-globin housekeeping gene (2 copies/genome). This additional step allowed for relative quantification of the input DNA level and attribution of the final quantity as the number of viral copies/genome/cell.20

The cut-off value for HPV16 positive status of >0.03 (>3 HPV genome copy/100 cells) by real-time quantitative PCR was based on interrogation of formalin-fixed DNA from a separate cohort of 31 HNSCC previously typed using the Linear Array HPV Genotyping test (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and conventional PCR (Table 1). The lowest real-time quantitative PCR value for samples that were positive by the Linear Array and conventional PCR was 0.0305, illustrated for sample T30 in Table 1.

Table 1.

HPV16 Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Results: Determination of Cutoffs

| Real-Time Quantitative PCR | Roche | Conventional PCR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | HPV16 Copy No. per cell | HPV16 | HPV16 (101bp) |

HPV16 (173bp) |

| T1 | 0.003 | |||

| T2 | 0.0026 | |||

| T3 | 0.2337 | positive | positive | |

| T4 | 0.3228 | positive | positive | |

| T5 | 0.0031 | |||

| T6 | 0.1024 | |||

| T7† | 0.0252 | positive | ||

| T8 | 0.0015 | |||

| T9 | 0.0002 | |||

| T10 | 0.0038 | |||

| T11 | 0 | |||

| T12 | 0.0221 | |||

| T13 | 0.0009 | |||

| T14 | 101.3887 | positive | positive | |

| T15 | 0 | |||

| T16 | 239.3613 | positive | positive | |

| T17 | 0.0029 | |||

| T18 | 0 | |||

| T19 | 0 | |||

| T20 | 18.4387 | positive | positive | |

| T21 | 0.0037 | |||

| T22 | 0 | |||

| T23 | 0.2797 | positive | positive | |

| T24 | 0 | positive | ||

| T25 | 0.0037 | |||

| T26 | 1.2585 | positive | positive | |

| T27 | 0.0003 | |||

| T28 | 0 | |||

| T29 | 0.0718 | positive | positive | |

| T30** | 0.0305 ** | positive | positive | |

| T31 | 0 | positive | ||

Abbreviation: bp, base pairs

Lowest real-time quantitative PCR value considered positive for HPV (≥0.03)

T7 was positive for HPV31 by Roche

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to test association of HPV+ve with the other risk factors (race, stage, gender, age, smoking, alcohol, treatment, health insurance type). Kaplan-Meier and log rank test were used to compare survival time difference between patients with and without HPV. A multivariable analysis would be considered to test HPV effects on survival adjusting for the other clinical risk factors if an HPV effect was detected (p<0.05) at the univariate analysis level. To assess outcomes from this study for comparison to published data, ad-hoc analyses were conducted to examine survival difference among categories, particularly for HPV status, race, gender, treatment, and insurance type.

RESULTS

Of the 79 primary LSCC, 45 were Caucasian American (CA), 32 (41%) were African American (AA), 1 Hispanic and 1 Arab American; 38 were early stage, 40 late stage and 1 unknown stage. There were 60 males and 19 females. These patients were categorized into four treatment groups of surgery alone (no radiation or chemotherapy - No R/C: 22 HPV−ve, 4 HPV+ve), radiation only (R: 30 HPV−ve, 15 HPV+ve), radiation plus chemotherapy (R+C: 4 HPV−ve, 1 HPV+ve), and chemotherapy only (C: 1 HPV+ve). Although HPV is often associated with a basaloid histologic morphology, it was not noted for any of the cases in this cohort. Other cohort characteristics including age, smoking status, alcohol use, HPV status, insurance type and laryngeal subsite localization are presented in Table 2. The laryngeal subsites were determined by careful assessment of pathology and clinical notes. There were six cases where the tumor overlapped more than one site within the larynx (3 supraglottic + glottic [one was HPV +ve], 2 glottic + subglottic and 1 supraglottic + glottic + subglottic [HPV+ve] lesions). Patient follow-up through October 2009 identified recurrences for 4 of the 43 supraglottic cancers within the laryngeal site; all four were HPV−ve.

Table 2.

LSCC Cohort Characteristics

| Characteristics | HPV Negative N=56 (%) |

HPV Positive N=21 (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Over 65 years | 26 (46) | 9 (43) | 0.944 |

| 51-65 years | 21 (38) | 8 (38) | |

| Less than 50 years | 9 (16) | 4 (19) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 38 (68) | 20 (95) | 0.016 |

| Female | 18 (32) | 1 (5) | |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian American | 30 (54) | 15 (71) | 0.058 |

| African American | 26 (46) | 5 (24) | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 34 (61) | 14 (67) | 0.51 |

| Divorced | 7 (13) | 1 (5) | |

| Never Married | 6 (11) | 2 (10) | |

| Widowed | 8 (14) | 2 (10) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 2 (10) | |

| Highest Education | |||

| Completed high school | 2 (4) | 1 (5) | 1.000 |

| Unknown | 54 (96) | 20 (95) | |

| Overall Comorbidity | |||

| None | 10 (18) | 4 (19) | 0.351 |

| Mild | 31 (55) | 8 (38) | |

| Moderate | 8 (14) | 3 (14) | |

| Severe | 7 (13) | 6 (29) | |

| Pneumonia | |||

| No | 46 (82) | 20 (95) | 0.271 |

| Yes | 10 (18) | 1 (5) | |

| Family History | |||

| No | 7 (32) | 5 (63) | 0.21 |

| Yes | 15 (68) | 3 (38) | |

| Alcohol use* | |||

| No | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 46 (96) | 19 (100) | |

| Smoking | |||

| Current smoker | 32 (57) | 14 (67) | 0.823 |

| Past smoker | 21 (38) | 6 (29) | |

| Never smoker | 3 (5) | 1 (5) | |

| Insurance Type† | |||

| Hap | 12 (25) | 4 (21) | 0.001 |

| Other HMO | 7 (15) | 3 (16) | |

| Blue Cross | 0 (0) | 6 (32) | |

| Medicare | 28 (58) | 6 (32) | |

| Medicaid | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Desmoplastic Response | |||

| Absent | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.343 |

| Focal | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Patchy & Irregular | 12 (22) | 2 (10) | |

| Prominent & Diffuse | 38 (69) | 19 (90) | |

| Pattern of Invasion | |||

| Pushing Cohesive Borders | 3 (5) | 5 (24) | 0.102 |

| Solid Cords | 35 (64) | 10 (48) | |

| Thin Irregular Cords | 14 (25) | 6 (29) | |

| Single Cell | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Lymphocytic Response | |||

| Continuous rim | 24 (44) | 10 (48) | 0.909 |

| Patchy Infiltrate | 29 (53) | 10 (48) | |

| Absent | 2 (4) | 1 (5) | |

| Tumor Necrosis | |||

| None | 34 (62) | 14 (67) | 0.664 |

| Minimal | 8 (15) | 4 (19) | |

| Extensive | 13 (24) | 3 (14) | |

| Vascular Invasion | |||

| Not Identified | 47 (87) | 20 (95) | 0.429 |

| Identified | 7 (13) | 1 (5) | |

| Perineural Invasion | |||

| Not Identified | 49 (89) | 19 (90) | 1.000 |

| Identified | 6 (11) | 2 (10) | |

| Overall Grade | |||

| Well Differentiated | 7 (13) | 3 (14) | 0.8 |

| Moderately Differentiated | 36 (65) | 15 (71) | |

| Poorly Differentiated | 12 (22) | 3 (14) | |

| Stage§ | |||

| Early | 25 (46) | 11 (52) | 0.797 |

| Late | 29 (54) | 10 (48) | |

| Subsites | |||

| Supraglottis | 33 (59) | 9 (43) | |

| Glottis | 19 (34) | 9 (43) | |

| Subgottis | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Overlap lesions | 3 (5) | 3 (14) | |

| * missing for 10 LSCC |

no insurance information for 10 cases (8 HPV−ve and 2 HPV+ve)

1 unknown stage is HPV−ve

LSCC - laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma

HAP - Health Alliance Plan

HMO - Health Maintenance Organization

HPV16 was detected in 21/77 (27%) patients, 5 AA (16%), 15 CA (33%) and 1 Hispanic. HPV status for 2 patients was not available due to insufficient DNA (1 AA male and 1 Arab American male). There was a trend towards higher HPV prevalence in CA vs AA (p=0.058). HPV+ve status was significantly associated with gender (p=0.016); 34% (20/58) of males were HPV+ve vs 5% (1/19) of females. HPV and insurance type were significantly correlated (p=0.001). The Medicare group had more HPV−ve (28/56) than HPV+ve patients (6/21); the Blue Cross insurance group had only HPV+ve patients (6/6). There was no correlation between HPV status and stage (p=0.797).

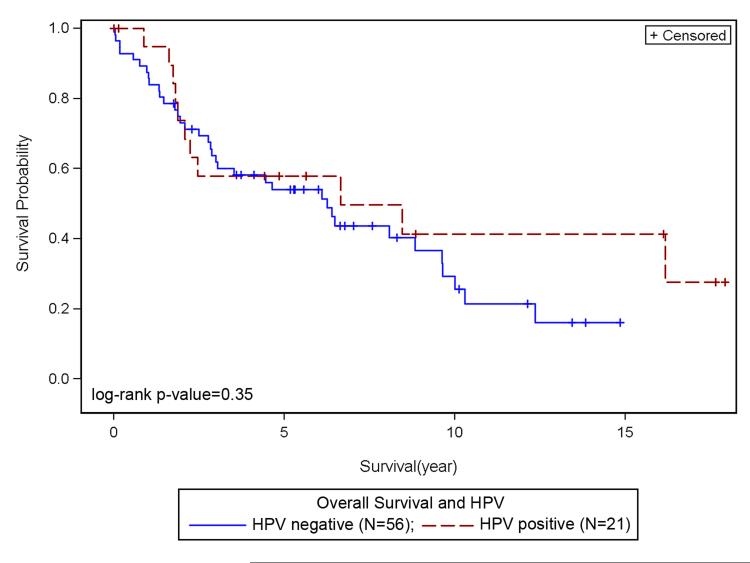

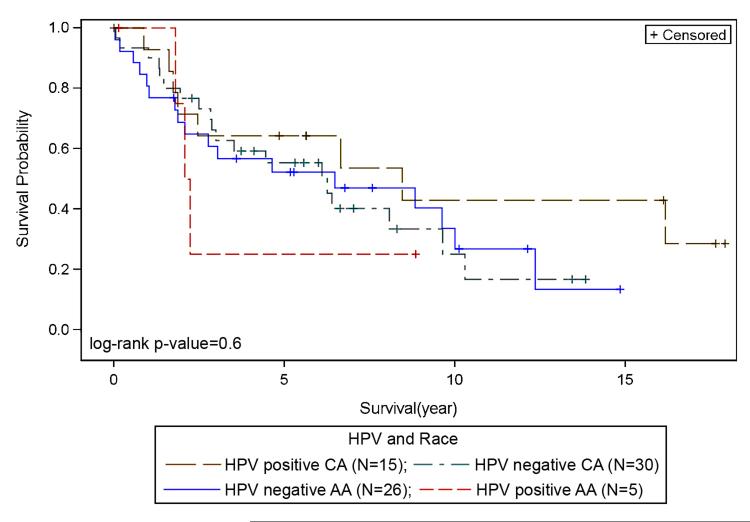

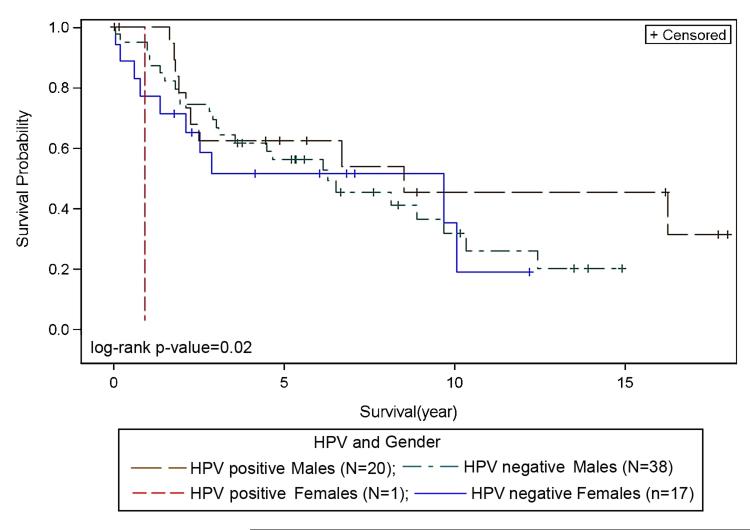

There was no significant association between overall survival, HPV status and race. However, Kaplan-Meier plots for overall survival and HPV status suggest slightly better survival for HPV+ve as compared to HPV−ve LSCC (Figure 1); HPV+ve LSCC had a slightly longer survival, with a median survival of 79.68 months compared to 75 months for HPV−ve patients (p=0.35). There was no statistically significant difference in survival among LSCC racial groups based on HPV status (p=0.6). HPV+ve CA appeared to show better survival when compared to HPV−ve CA (Figure 2), and HPV−ve CA and AA showed similar survival. Differences in survival between HPV−ve and HPV+ve AA were not discernable due to small numbers of AA cases (Figure 2). There was no correlation between HPV status and stage (p=0.33). Survival for HPV+ve late stage patients appeared better than HPV−ve late stage, and HPV+ve and HPV−ve early stage LSCC showed no differences in survival outcomes (not shown). With regard to treatment and HPV status, within the chemoradiation treatment group (R, R+C, not shown), HPV+ve LSCC patients showed better survival outcomes when compared to HPV−ve. Among racial groups, HPV+ve CA patients show better survival outcomes when compared to HPV+ve AA patients, however this was not significant (not shown). HPV was correlated with gender (p=0.02). Survival appeared better for HPV+ve males when compared to HPV−ve males (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Survival and HPV status.

Better survival noted for HPV+ve as compared to HPV−ve LSCC.

Figure 2. Survival with respect to HPV and Race.

HPV+ve CA shows better survival when compared to HPV−ve CA. HPV−ve CA and AA survival appear similar. Survival differences between HPV−ve and HPV+ve AA were not discernable due to smaller numbers of AA cases.

CA – Caucasian American, AA – African American

Figure 3. Survival with respect to HPV and Gender.

Better overall survival noted for HPV+ve males as compared to HPV+ve and HPV −ve females.

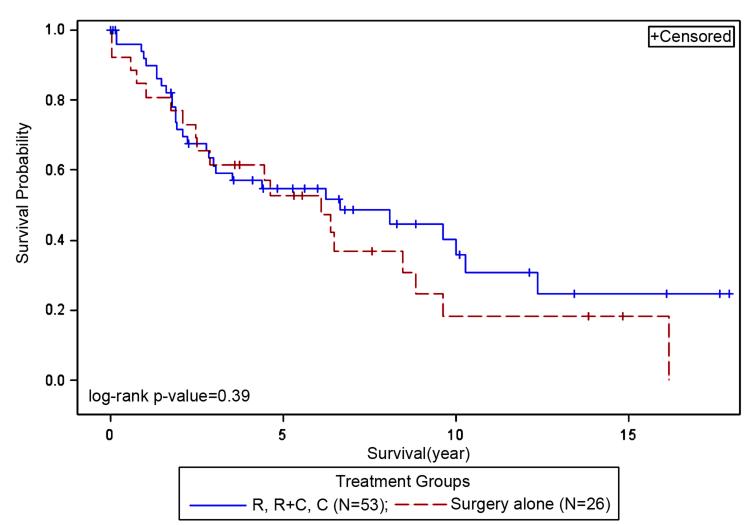

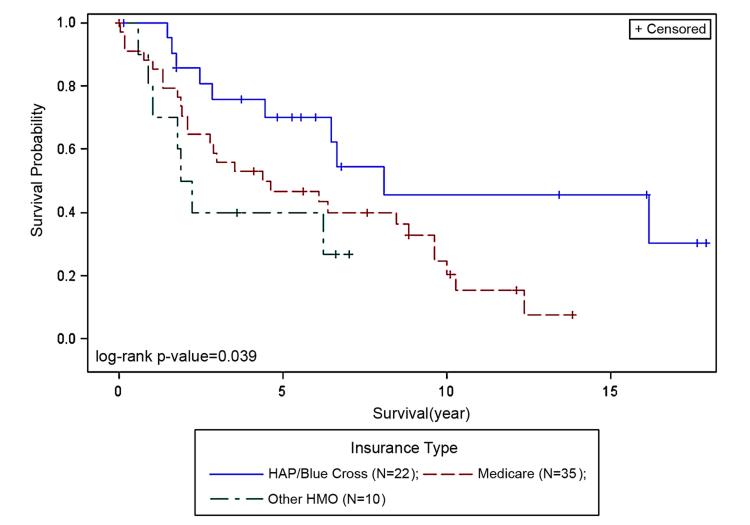

There was no difference in survival between the treated (R, R+C or C) and the surgery alone group (p=0.39, Figure 4). Insurance payor type was attributed to 86% of the cohort; 14% lacked insurance information. Survival and insurance payor type showed significant correlation (p=0.039, Figure 5). Patients with private insurance (HAP/Blue Cross, reference) had better survival when compared to Medicare (p=0.034) or other HMO groups (p=0.036). There was no difference in survival between the Medicare and other HMO groups.

Figure 4. Survival and Treatment groups.

There was no difference in survival between the treated (R, R+C or C) and the surgery alone group (no radiation or chemotherapy).

R – radiation only, R+C – Radiation plus Chemotherapy, C – Chemotherapy only

Figure 5. Survival and Insurance payor type.

Patients with HAP/Blue Cross (reference) had better survival when compared to Medicare (p=0.034) or other HMO groups (p=0.036). There was no difference in survival between the Medicare and other HMO groups.

Kaplan-Meier plots by race and insurance type show small but interesting differences (not shown); AA and CA patients with Medicare had similar survival. CA patients with HAP or Blue Cross had better survival outcomes as compared to the Medicare group. For AA LSCC, the Medicare group had the largest number of patients (17/32) and indicated better survival than AA LSCC with other insurance types, which had fewer patients.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of oncogenic HPV types in LSCC has a wide distribution, ranging from 0%21 to 69%,22 and indicates some controversy whether HPV is implicated in laryngeal cancer. Torrente et al.23 believe the prevalence in LSCC varies so widely because of differences in methods of HPV detection as well as selection bias due to small sample size or poor quality of cancer specimen. Real-time quantitative PCR is a more reliable method for quantifying viral load with minimal chance for contamination due to isolated wells. Other advantages of real-time quantitative PCR include the ability to give a quantity of input template, absence of post-PCR processing, and allowance for relative quantitation of multiple target templates.24 In a pooled meta analysis study7 of 5046 head and neck cancers, of which 1435 were laryngeal cancers, HPV DNA was identified in 24% of tested laryngeal tumors (95% confidence interval [CI], 21.8– 26.3) using conventional PCR based assays. HPV16 was the main genotype detected with differences in prevalence among anatomic sites, with a prevalence of 17% in the laryngeal cases.7 In our study, HPV16, detected by real-time quantitative PCR, was present in 27% of the cohort, supporting a role for HPV in LSCC.21, 22

HPV+ve patients with HNSCC, particularly those with oropharyngeal cancer,25 have improved prognosis, however, for LSCC, this remains to be established. In this LSCC cohort, HPV+ve patients had slightly longer survival than HPV−ve, but did not reach statistical significance likely due to sample size limitations. The significant association between HPV positivity and male gender (p=0.016) is likely due to the higher incidence of HNSCC in men (3:1 ratio). The significant correlation between HPV and insurance type (p=0.001) point to interesting observations among insurance groups. Of particular interest is the finding that the Medicare group had more HPV−ve (58% vs 32%) HNSCC. In a separate much larger HNSCC cohort from our group (oral personal communication from Dr. Maria J. Worsham), older patients in the over-65 age group were 55% less likely to be HPV+ve than those in the ≤50 group (OR=0.45, 95% CI 0.22, 0.89, p=0.021).

We detected trends similar to oropharyngeal cancer for prevalence of HPV with respect to HPV status and race. Prevalence of HPV in CA LSCC was 33% and 16% in AA (p=0.058) and is much higher than that reported by Settle et al.25 for oropharyngeal SCC (34% CA vs 4% AA). It is important to note that Settle et al.25 had 28 AA patients, only 1 of whom was HPV16+ve by conventional PCR. Though lacking statistical significance, HPV+ve CA patients in our study showed better survival when compared to HPV−ve CA and AA patients; HPV−ve CA and AA patients had comparative survival, a pattern similar to studies reported in oropharyngeal cancer.

We found no significant association between HPV status and clinical stage (early vs late) concurring with Baumann et al.26 There were about equal numbers of early (N=38) and late stage (N=40) LSCC with approximately equal numbers of HPV+ve cases in both groups. Though lacking statistical significance, better survival outcomes for HPV+ve late stage cases when compared to HPV−ve late stage cases were noted with similar survival outcomes for HPV+ve and HPV−ve early stage LSCC. HPV+ve late and early stage cases who received treatment (radiation, chemotherapy or chemoradiation) showed better survival outcomes when compared to HPV+ve late and early stage cases who received surgery alone.

In an oropharyngeal cancer cohort, Worden et al.27 reported that a greater proportion of men than women were HPV+ve and that female gender was significantly associated with poor disease-specific survival. In our study, the proportion of HPV+ve LSCC was nearly 7-fold higher in males (20 of 58, 34%) than in female patients (1 of 19, 5%; p=0.016) and while survival plots show HPV+ve males with better overall survival as compared to HPV−ve males, in females small sample sizes were a limiting factor.

In our current study, for overall survival, HPV+ve LSCC had a slightly longer survival, with a median survival of 79.68 months compared to 75 months for HPV−ve patients, though this was not significant. Among LSCC racial groups, HPV+ve CA showed better survival when compared to HPV−ve CA (Figure 2); HPV−ve CA and AA had similar survival. Within the AA group, differences in survival between HPV−ve and HPV+ve were not discernable due to smaller numbers of AA cases (Figure 2).

Settle et al.25 demonstrated better overall survival for HPV+ve over HPV−ve HNSCC receiving combined chemotherapy and radiation mainly due to improved overall survival in the oropharyngeal subgroup. We found no significant difference in survival between LSCC patients who received radiation treatment alone and those who received surgery alone (no radiation or chemotherapy). Nevertheless, survival plots indicate that HPV+ve patients who received chemoradiation had better survival when compared to HPV−ve LSCC. Also HPV+ve CA patients displayed better survival than HPV+ve AA patients, however, this was not significant and likely due to the small numbers in the HPV+ve AA group (N=5).

Lack of health insurance is a barrier to accessing optimal health care for HNSCC. Also insurance type often dictates access to prevention and early detection, including regular health care checkups and seeking care for symptomatic disease (i.e., the delay between first seeking care and definitive diagnosis).28 Kwok et al.29 studied the impact of health insurance status on the survival of HNSCC patients and found that patients with Medicaid/uninsured and Medicare disability had significantly lower overall survival compared with patients with private insurance. We also observed improved survival outcomes for those with private insurance (HAP/Blue Cross) when compared to Medicare (p=0.034). Also, CA patients with HAP and Blue Cross appeared to have better survival when compared to the Medicare group while CA and AA Medicare patients had similar survival.

Studies in the past have shown that HPV status and smoking history are inversely correlated in HNSCC.30, 31 Baumann et al.26 confirmed this finding in an early stage laryngeal cancer cohort where 67% of HPV+ve tumors were in patients who never smoked versus 22% of HPV−ve patients with no smoking history. The majority of patients in our cohort had a history of smoking (95%). Of the 4 patients who never smoked only 1 was HPV+ve.

This study shows slightly better survival for HPV+ve LSCC versus HPV−ve. Larger multi ethnic LSCC cohorts are needed to more clearly delineate HPV related stage and survival outcomes across ethnicities. Identification of such LSCC patient subsets should result in more optimized treatment approaches to improve overall survival and quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Drs. Stephen and Worsham had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This study was supported by R01 NIH DE 15990 (Dr. Worsham).

Footnotes

Podium presentation at the 2011 AAO-HNSF Annual Meeting & OTO EXPO, San Francisco, CA, September 11-14, 2011

REFERENCES

- 1.Gillison ML, Lowy DR. A causal role for human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer. Lancet. 2004 May 8;363(9420):1488–1489. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000 May 3;92(9):709–720. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 1;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007 May 10;356(19):1944–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen AA, Marsit CJ, Christensen BC, et al. Genetic variation in the vitamin C transporter, SLC23A2, modifies the risk of HPV16-associated head and neck cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2009 Jun;30(6):977–981. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dayyani F, Etzel CJ, Liu M, Ho CH, Lippman SM, Tsao AS. Meta-analysis of the impact of human papillomavirus (HPV) on cancer risk and overall survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) Head Neck Oncol. 2010;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005 Feb;14(2):467–475. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer is a distinct epidemiologic, clinical, and molecular entity. Semin Oncol. 2004 Dec;31(6):744–754. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munger K, Baldwin A, Edwards KM, et al. Mechanisms of human papillomavirus-induced oncogenesis. J Virol. 2004 Nov;78(21):11451–11460. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11451-11460.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen M, Song S, Liem A, Androphy E, Liu Y, Lambert PF. A mutant of human papillomavirus type 16 E6 deficient in binding alpha-helix partners displays reduced oncogenic potential in vivo. J Virol. 2002 Dec;76(24):13039–13048. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.13039-13048.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Feb 20;100(4):261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fakhry C, Gillison ML. Clinical implications of human papillomavirus in head and neck cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jun 10;24(17):2606–2611. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Settle K, Posner MR, Schumaker LM, et al. Racial survival disparity in head and neck cancer results from low prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in black oropharyngeal cancer patients. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2009 Sep;2(9):776–781. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sethi S, Lu M, Kapke A, Benninger MS, Worsham MJ. Patient and tumor factors at diagnosis in a multi-ethnic primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cohort. J Surg Oncol. 2009 Feb 1;99(2):104–108. doi: 10.1002/jso.21190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piccirillo JF, Costas I, Claybour P, Borah AJ, Grove L, Jeffe D. The Measurement of Comorbidity by Cancer Registries. Journal of Registry Management. 2003;30(1):8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naqvi K, Garcia-Manero G, Sardesai S, et al. Association of comorbidities with overall survival in myelodysplastic syndrome: development of a prognostic model. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jun 1;29(16):2240–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen K, Sawhney R, Khan M, et al. Methylation of multiple genes as diagnostic and therapeutic markers in primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007 Nov;133(11):1131–1138. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.11.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo YM, Tein MS, Lau TK, et al. Quantitative analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum: implications for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998 Apr;62(4):768–775. doi: 10.1086/301800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.P Peitsaro, B Johansson, S Syrjanen. Integrated human papillomavirus type 16 is frequently found in cervical cancer precursors as demonstrated by a novel quantitative real-time PCR technique. J Clin Microbiol. 2002 Mar;40(3):886–891. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.3.886-891.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.User Bulletin #2: ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System. Perkin-Elmer Corporation; Foster City, CA: 1997. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallo A, Degener AM, Pagliuca G, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus and adenovirus in benign and malignant lesions of the larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009 Aug;141(2):276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallegos-Hernandez JF, Paredes-Hernandez E, Flores-Diaz R, Minauro-Munoz G, Apresa-Garcia T. Hernandez-Hernandez DM. [Human papillomavirus: association with head and neck cancer] Cir Cir. 2007 May-Jun;75(3):151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torrente MC, Rodrigo JP, Haigentz M, Jr., et al. Human papillomavirus infections in laryngeal cancer. Head Neck. Apr 29; doi: 10.1002/hed.21421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha PK, Pai SI, Westra WH, et al. Real-time quantitative PCR demonstrates low prevalence of human papillomavirus type 16 in premalignant and malignant lesions of the oral cavity. Clin Cancer Res. 2002 May;8(5):1203–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Settle K, Posner MR, Schumaker LM, et al. Racial survival disparity in head and neck cancer results from low prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in black oropharyngeal cancer patients. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009 Sep;2(9):776–781. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumann JL, Cohen S, Evjen AN, et al. Human papillomavirus in early laryngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2009 Aug;119(8):1531–1537. doi: 10.1002/lary.20509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Worden FP, Kumar B, Lee JS, et al. Chemoselection as a strategy for organ preservation in advanced oropharynx cancer: response and survival positively associated with HPV16 copy number. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jul 1;26(19):3138–3146. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen AY, Schrag NM, Halpern M, Stewart A, Ward EM. Health insurance and stage at diagnosis of laryngeal cancer: does insurance type predict stage at diagnosis? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007 Aug;133(8):784–790. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.8.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwok J, Langevin SM, Argiris A, Grandis JR, Gooding WE, Taioli E. The impact of health insurance status on the survival of patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. Jan 15;116(2):476–485. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorgoulis VG, Zacharatos P, Kotsinas A, et al. Human papilloma virus (HPV) is possibly involved in laryngeal but not in lung carcinogenesis. Hum Pathol. 1999 Mar;30(3):274–283. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrero R, Castellsague X, Pawlita M, et al. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Dec 3;95(23):1772–1783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]