Abstract

The bimodular 276 kDa nonribosomal peptide synthetase AspA from Aspergillus alliaceus, heterologously expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, converts tryptophan and two molecules of the aromatic β-amino acid anthranilate (Ant) into a pair of tetracyclic peptidyl alkaloids asperlicin C and D in a ratio of 10:1. The first module of AspA activates and processes two molecules of Ant iteratively to generate a tethered Ant-Ant-Trp-S-enzyme intermediate on module two. Release is postulated to involve tandem cyclizations, in which the first step is the macrocyclization of the linear tripeptidyl-S-enzyme, by the terminal condensation (CT) domain to generate the regioisomeric tetracyclic asperlicin scaffolds. Computational analysis of the transannular cyclization of the 11-membered macrocyclic intermediate shows that asperlicin C is the kinetically favored product due to the high stability of a conformation resembling the transition state for cyclization, while asperlicin D is thermodynamically more stable.

INTRODUCTION

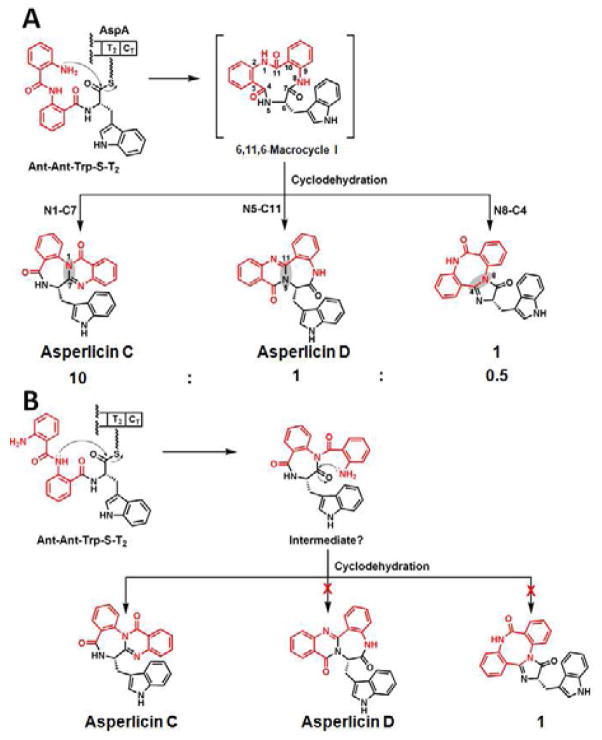

The aspergilli are prolific producers of polyketide and nonribosomal peptide natural products, some of which appear to be constitutive while others are conditional metabolites (Bok, et al., 2006; Sanchez, et al., 2012). The peptidyl alkaloids represent a prevalent class, typified by fused ring scaffolds with rigidified frameworks and extended molecular architectures (Chang, et al., 1985; Gao, et al., 2011; Karwowski, et al., 1993; Liesch, et al., 1988; Takahashi, et al., 1995). These are assembled efficiently by short nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) assembly lines (Finking and Marahiel, 2004; Sattely, et al., 2008) and then further modified by post-assembly line tailoring enzymes that can add electrophilic acyl, prenyl, and oxygen functionalities in scaffold maturation events (Ames, et al., 2010; Haynes, et al., 2011; Yin, et al., 2009). We have recently examined the chemical logic and enzymatic machinery for assembly of Aspergillus signature metabolites such as fumiquinazolines from Aspergillus fumigatus (Ames, et al., 2011; Ames and Walsh, 2010), ardeemins from Aspergillus fischeri (Haynes, et al., 2013) and asperlicins from Aspergillus alliaceus (Haynes, et al., 2012), which are notable for utilizing the nonproteinogenic β-amino acid anthranilate (Ant) as a chain-initiating building block (Walsh, et al., 2012; Walsh, et al., 2013) (Figure 1A). The tricyclic scaffold of fumiquinazoline F is assembled from Ant, L-tryptophan (L-Trp), and L-alanine (L-Ala) by trimodular NRPS enzymatic action (Gao, et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Heterologous expression of AspA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. (A) Amino acid building blocks for assembly of fumiquinazoline F (FQF), and asperlicins C and D. AspA is a 276 kDa two-module NRPS enzymes with the indicated Adenylation (A), Thiolation (T) and Condensation (C) domains. The terminal condensation domains (CT) of TqaA and AspA act as cyclization/release catalysts for Ant-D-Trp-L-Ala and Ant-Ant-L-Trp, respectively, presented as thioesters on the pantetheinyl arms of immediate upstream T domains. Intramolecular capture of the thioester carbonyl by the NH2 of Ant1 is the proposed common release mechanism. The subsequent transannular cyclizations and aromatizing dehydrations yield 6,6,6-tricyclic quinazolinedione (fumiquinazoline F) or tetracyclic 6,6,7,6 asperlicin C/D regioisomeric scaffolds, affected by the presence or absence of Ant2 in the tripepitidyl-S-thiolation domain intermediates. (B) SDS-PAGE gel of AspA expressed and purified from S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NgpA.

In analogy, two molecules of Ant and one L-Trp building block are processed to the tetracyclic isomers asperlicin C and asperlicin D (Haynes, et al., 2012). Surprisingly, the AspA NRPS presumed to assemble these asperlicin isomeric frameworks is predicted to be bimodular not trimodular by bioinformatic identification and subsequent genetic deletion analysis in the producer (Haynes, et al., 2012). This suggests either an unusual iterative action in Ant activation or a possible third module encoded elsewhere in the A. alliaceus genome acting in trans with AspA. In this work we have expressed the 276 kDa AspA protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, purified it in soluble active form, and shown that it is necessary and sufficient to produce both asperlicin C and D in a constant ratio, indicating they derive from a common intermediate. These tetracyclic product regioisomers represent a dramatic morphing of the linear tripeptide backbone of Ant-Ant-Trp.

RESULTS

Expression and Purification of A. alliaceus AspA

To obtain the 276 kDa hexa-domain bimodular (A1-T1-C2-A2-T2-CT: where A = Adenylation, T = Thiolation and C = Condensation domains; CT represents a terminal condensation domain at the end of the NRPS assembly line) NRPS AspA (Figure 1A) from A. alliaceus as a purified protein for catalytic characterization, we utilized S. cerevisiae strain BJ5464-NpgA that has vacuolar proteases deleted and contains a phosphopantetheinyl transferase (NpgA) that primes the apo forms of NRPS carrier domains (Ma, et al., 2009). We have previously found that this yeast strain will provide the TqaA trimodular NRPS in soluble, active form (Gao, et al., 2012). The DNA encoding the aspA gene was cloned by PCR with reverse transcription (RT-PCR) in six sections and one intron of 63 base pairs (bp) was removed from fragment 1 before ligation to yield a 7329 bp coding sequence, as described in EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES. The full length aspA gene with a C-terminal His6 tag was then moved into the S. cerevisiae strain for expression and affinity purification.

As shown in Figure 1B the tagged AspA protein could be purified to apparent homogeneity in soluble form with a yield of 9 mg L−1. No proteolytic fragments were detected, suggesting the six domain protein is likely well folded.

Assay of the Adenylation Domains of AspA for Amino Acid Activation

The scaffolds of the suite of known asperlicin metabolites suggest that two molecules of Ant and one tryptophan are utilized as building blocks (Haynes, et al., 2012). The purified AspA protein was assayed for the ability to form the aminoacyl-AMPs from Ant and L-Trp via amino acid-dependent exchange of radioactivity from 32PPi into ATP, a classical assay for reversible formation of acyl-adenylates (Linne and Marahiel, 2004). As shown in Figure 2A, Ant supports robust exchange activity with kcat = 1.6 sec−1, while L-Trp is also active with lower rates (kcat = 1.5 min−1, Figure S1). No significant activity was detected with other proteinogenic amino acids. Benzoate and salicylate as Ant analogs also gave evidence of reversible formation of the acyl-AMPs (Figure S1). Ant-L-Trp, Ant-D-Trp and Ant-Ant dipeptides didn’t support exchange, suggesting they are not utilized as free intermediates (Figure 2A).

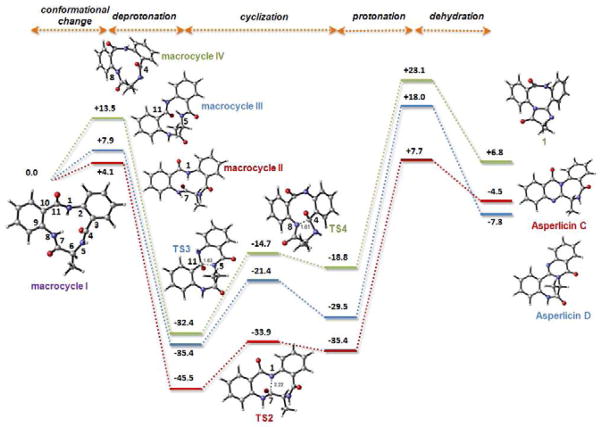

Figure 2.

Anthranilate and L-tryptophan are substrates of AspA. (A) ATP-[32P]PPi exchange assay of full length AspA; (B) Loading assay of A1-T1-C2 (M1) and C2-A2-T2-CT (M2) with [14C]anthranilate or [14C]tryptophan. M1 activates Ant while M2 activates L-Trp. Assay components are labeled in the figure. Data represent mean values ± s.d.

We also successfully cloned and expressed protein fragments spanning the two AspA modules. The A1-T1 construct was not solubly expressed but the A1-T1-C2 tridomain (150 kDa) representing Module 1 (M1) was soluble at a yield of 15 mg L−1). Likewise A2-T2-CT was not soluble, but the four domain C2-A2-T2-CT (176 kDa) representing Module 2 (M2) version was soluble at a yield of 10 mg L−1 (Figure S2). As shown in Figure 2A, these protein constructs allowed unambiguous assignment that the A1 domain in M1 activates Ant; and A2 in M2 activates L-Trp. This result therefore strongly indicates the iterative use of Ant by M1 in synthesis of the tripeptide. In addition, it was possible to express and purify in soluble form of the terminal CT (52 kDa, yield 4 mg L−1) and the didomain T2-CT (61 kDa, yield 16 mg L−1) fragment from M2 (Figure S2), which proved useful in studies with di- and tripeptidyl-S-N-acetylcysteamine (SNAC) surrogate substrates noted later.

Holo-AspA is Catalytically Competent to Generate Both Asperlicin C and D and Another Product Isomer

Having isolated the intact AspA protein and verified its A domains are catalytically active, we next examined if the bimodular NPRS can produce the tripeptidyl alkaloids. When 10 μM pure AspA was mixed with 1 mM Ant, 1 mM L-Trp, 3 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2 in 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5 for 16 hours; and small molecules analyzed by HPLC, Figure 3A shows new major and minor peaks which chromatograph with the elution times of standard asperlicin C and asperlicin D (Haynes, et al., 2012), respectively. Analysis of the peaks by mass spectrometry confirmed that both product peaks had m/z = 407 [M + H]+, equal to that of both asperlicin C and D isomers (Figure S3). There is one additional enzyme-dependent minor product peak detectable in the HPLC traces, product 1, and it too has the same m/z = 407 [M + H]+ mass.

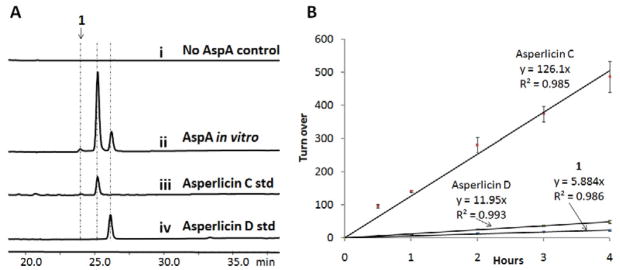

Figure 3.

In vitro reconstitution of AspA. (A) LC/MS analysis (280 nm) shows purified AspA generates asperlicin C/D and a third product 1 of identical mass from Ant, L-Trp, and ATP; (B) Catalytic turnover number and product partition ratios for 1, asperlicin C and D production. Both asperlicin C and D standards were synthesized from our previous study (Haynes, et al., 2012).

Rate assays under those conditions indicate linear formation rates for asperlicin C/D and the unknown product 1 (Figure 3B). Given the known extinction coefficients (almost the same at 280 nm) of the asperlicin C and D synthetic standards, the apparent turnover number for asperlicin C was calculated to be 126.1 ± 7.6 h−1 and asperlicin D is 12.0 ± 0.8 h−1. That product ratio of ~10:1 does not change during the course of the incubation, suggesting the minor product asperlicin D is not forming from asperlicin C in a post reaction transformation, but is in fact an initially formed alternative product of AspA. Until the structure of the third isomeric product 1 is determined, we cannot confidently assign a turnover number to it. However, assuming this is a novel asperlicin isomer and might have a comparable A280 extinction coefficient, we would estimate an apparent turnover number of ~5.9 ± 0.3 h−1 which represents 5% of the product flux that is also constant over the incubation time frame. Hence, all three products are likely derived from the same precursor, which we proposed to be an 11-membered macrolactam formed via macrocyclization of the tripeptide.

Assay of Truncated Forms of AspA for Product Formation: Activity of the Two Modules

To examine the iterative features of AspA, we dissected the AspA NRPS into M1 and M2. Mixing of the purified M1 and M2 with Ant, L-Trp and ATP gave reconstitution of asperlicin production with asperlicin C and D in the same ratio as full length AspA and also the third minor product 1 (Figure S4). This validates the dissected modules can work in trans and the tethered, activated anthranilyl moiety can be transferred productively to M2. It seemed likely that the second condensation domain C2 would work twice in a catalytic cycle of AspA, first in the canonical mode to condense T1-tethered Ant onto Trp-S-T2 to yield Ant-L-Trp-S-T2 and concomitantly free the thiol in T1-SH (where -S-T# designates the S-pantetheinyl thiolation domain in module #). If that Ant-L-Trp-S-enzyme had a sufficiently long lifetime, T1 could re-load with another Ant; a second round of transfer catalyzed by C2 would generate Ant-Ant-L-Trp-S-T2. We sought to test these two predictions by synthesis of dipeptidyl Ant-L-Trp-SNAC, tripeptidyl Ant-Ant-L-Trp-SNAC and adding them as surrogate substrates to particular purified fragments of AspA. The expectation was that HS-pantetheinyl-T2 could engage in thioester exchange with the di- and tripeptidyl-SNACs to generate the corresponding Ant-L-Trp-S-T2 and Ant-Ant-L-Trp-S-T2 forms, respectively, to allow evaluation of their catalytic competence.

To evaluate whether Ant-L-Trp-S-T2 was on pathway, the purified terminal didomain T2CT (50 μM) was employed and converted to holo form by prior phosphopantetheinylation via the phosphopantetheinyltransferase Sfp and CoA-SH (Quadri, et al., 1998). In parallel, holo M1 (50 μM) was incubated with Ant and ATP to produce the covalent Ant-S-T1 form. Then the two proteins were combined, 400 μM synthetic Ant-L-Trp-SNAC was added, and product formation assayed after 1 hour. As shown in Figure 4a (trace ii), products with the diagnostic UV of asperlicins were detected; the anticipated pattern of asperlicin C/D and 1 were detected by LC/MS analysis with focus on extracted ion m/z = 407 [M + H]+ (Figure S5). Nonenzymatic cyclization of Ant-L-Trp-SNAC to the bicyclic benzodiazepinedione and hydrolysis of the thioester to Ant-L-Trp acid compete with the enzymatic consumption as we have reported previously (Gao, et al., 2012). In the absence of the AspA fragments, these spontaneous products were the only compounds detected (Figure 4A, trace i). Panel B of Figure 4 shows the proposed acyl exchange between SNAC and HS-pantetheinyl-T2 to yield the Ant-L-Trp-S-T2 which is competent to receive the Ant moiety on T1 and proceed through the catalytic cycle.

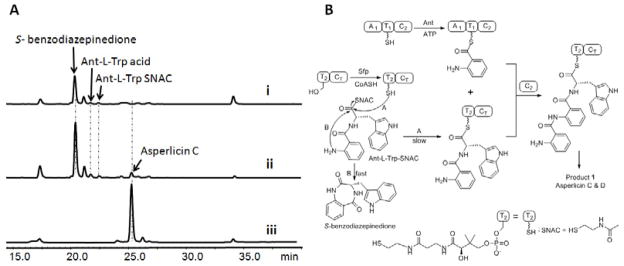

Figure 4.

The first module of AspA iteratively utilizes two molecules of Ant. (A) The dipeptidyl Ant-L-Trp-SNAC (Gao, et al., 2012) is a surrogate substrate for M2 of AspA: the holo form of M1 (50 μM A1-T1-C2) was preloaded with Ant (1 mM Ant, 3 mM ATP) for 1 hour while in parallel the T2-CT didomain was converted to the holo (HS-pantetheinyl) form using 20 μM Sfp and 1mM CoASH. The two solutions were mixed with addition of 400 μM Ant-L-Trp-SNAC and incubated overnight before aliquots were analyzed by LC/MS (280 nm). Trace i shows the spontaneous products (S-benzodiazepinedione and Ant-L-Trp acid) formed from an assay without T2CT di-domain; trace ii shows products formed from an assay including holo T2CT. In addition to the spontaneously formed products, formation of asperlicin C can be detected. Trace iii shows the profile of products formed from full length AspA starting from Ant, L-Trp and ATP. (B) Reaction scheme: M1 loaded covalently with Ant on the pantetheinyl arm of T1 reacts with Ant-L-Trp-S-pantetheinyl-T2-CT to yield the tripeptidyl Ant-Ant-L-Trp-S-T2-CT form of the bi-domain T2-CT protein fragment. That can be acted on by CT to yield asperlicin C, D and 1. The added Ant-L-Trp- SNAC is proposed to undergo acyl exchange onto the HS-pantetheinyl arm of T2-CT in competition with hydrolysis to Ant-L-Trp and intramolecular cyclization to S-benzodiazepinedione.

T2CT Bidomain Converts Ant-Ant-L-Trp-SNAC to the Suite of Asperlicin Products

The above results suggest that Ant-Ant-L-Trp-S-T2 will be formed from Ant-S-T1 and Ant-L-Trp-S-T2 during the AspA catalytic cycle (Figure 4B). To evaluate that directly we prepared the corresponding Ant-Ant-L-Trp-SNAC and added it to either the purified CT domain or to the purified T2CT protein construct. As shown in Figure 5A trace iv, no asperlicins are generated in the absence of AspA fragments, demonstrating the tripeptidyl thioester (unlike the Ant-Trp-SNAC) is stable in solution and any cyclization requires the action of an enzyme, most likely the CT. However, the isolated CT domain was incompetent (trace iii) but the T2CT (trace i) was able to generate the characteristic trio of asperlicin products at m/z = 407 [M + H]+ in the presence of the tripeptide-SNAC as assessed in an overnight incubation (Figure S6). Thus, the T2 domain appears essential in recognition/presentation of the tripeptide by the CT domain. In a prior study by us (Gao, et al., 2012), the same requirement held for presentation of Ant-D-Trp-L-Ala to the CT domain of TqaA as a thioester bound to the immediately upstream T in that fumiquinazoline F-generating trimodular NRPS. In the absence of CoA and Sfp, assay containing T2CT still produced ~80% yield of the same product mixture as shown in trace ii. Taken together, we propose asperlicin formation in trace i and ii was initiated by the nonenzymatic transfer of the Ant-Ant-L-Trp moiety from SNAC to the HS-pantetheinyl arm of T2 (Figure 5B) through thioester interchange. At that juncture the downstream CT domain can catalyze the intramolecular amide bond formation(s) that constitutes release of the nascent cyclic product.

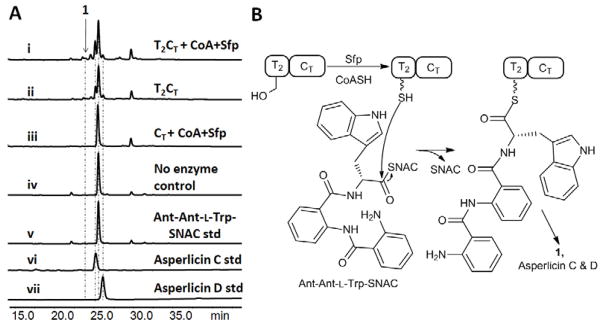

Figure 5.

The T2CT di-domain fragment of AspA generates asperlicin C and D from exogenous Ant-Ant-L-Trp-SNAC. (A) Panel A shows UV-vis analyses of HPLC traces (280 nm) from the indicated incubations. Reactions contained 50mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, in 100 μL. Reactions represented by traces i to iv contained 100 μM Ant-Ant-L-Trp-SNAC. 50 μM T2CT, 20 μM Sfp and 2 mM CoASH were added to reaction I; but only 50 μM T2CT was added in reaction ii; 50 μM CT, 20 μM Sfp and 2 mM CoASH were added in reaction iii; No enzyme was added in reaction iv. Traces (v to vii) are standards. The suite of asperlicin C, D and 1([M+H]+ = 407) are found in traces i and ii but not iii and iv. (B) Reaction scheme featuring nonenzymatic acyl exchange from the –SNAC to the T2 domain pantetheinyl thiol arm to yield the tripeptidyl-S-T2 covalent enzyme as substrate for cyclizing release by the downstream CT domain.

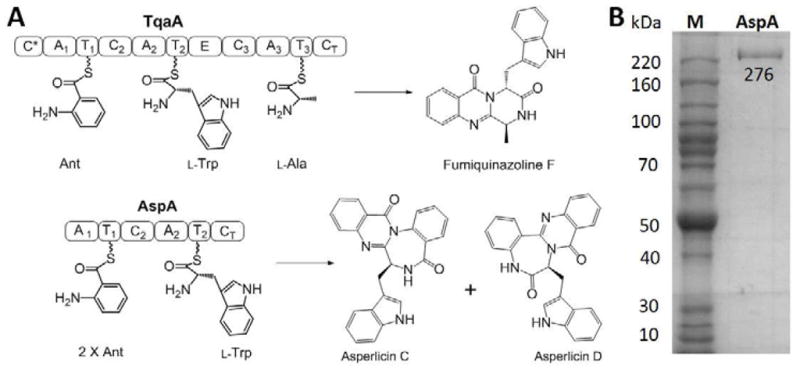

Proposed Cyclization Mechanisms of Asperlicin C and D and Computation Prediction of Product Distributions

Insight into that common released precursor from AspA comes from inspection of the differences between the isomeric asperlicin C and D and their molecular connectivity (Figure 6). The mechanistic assumption, which is supported by the reconstitution studies with intact and dissected AspA, is that the linear Ant-Ant-Trp-S-T2, tripeptidyl-S-enzyme is a late intermediate. The terminal condensation domain CT would then act to release the tripeptidyl chain by cyclization, analogous to that demonstrated role by the CT domain of TqaA as it releases tricyclic fumiquinazoline F (Gao, et al., 2012). While an alternative macrocyclization mechanism may be considered as detailed in the DISCUSSION section, the aniline NH2 of Ant1 will likely be the most competent nucleophile (Figure 6A). That release step (attack of N8 on (C7=O)) would generate a tricyclic product 6,11,6-macrocycle I, fully analogous to the 6,10-bicyclic product (vide infra) we have proposed in TqaA action to generate fumiquinazoline F (FQF) (Gao, et al., 2012) (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 6A, the 11-membered macrocycle I could be subject to transannular attack with three different regiochemistries, by attack of each of the three amide nitrogen (N1, N5, N8) on one of the three carbonyls [(C4=O), (C7=O), (C11=O)].

Figure 6.

Mechanistic proposal for generation of a constant ratio of asperlicin C (major) and asperlicin D (minor) from macrocyclizing release of a linear Ant-Ant-LTrp-S-T2 thioester by the CT domain. (A) The attack of the free NH2 of the Ant1 residue generates a transient 6,11,6-tricyclic product macrocycle I. Subsequent transannular attack and dehydration can proceed with distinct regiochemistries of intramolecular amide capture of carbonyl groups: N1 on C7=O gives major product asperlicin C, N5 on C11=O gives asperlicin D, while N8 on C4=O could give a third asperlicin regioisomer, putative product 1. Whether these steps happen in one of the active sites of AspA or in solution have not yet been determined. (B) Alternative mode of tripeptidyl chain release by initial attack of the amide NH of Ant2 residue on the thioester carbonyl would yield a diketopiperazine as nascent product. That can go on to asperlicin C as shown but has the wrong connectivity to generate the observed minor product asperlicin D and 1 and so is ruled out.

Attack of N1 on (C7=O) across the ring generates a new 6-membered and a 7-membered ring, converting the nascent macrocycle I into a tetracyclic framework. Loss of water from the initial addition product yields the major product (~85% of the final product flux) asperlicin C. Alternatively, amide N5 could capture (C11=O). This also builds new 6- and 7-membered rings, generating a regioisomeric tetracyclic scaffold, a dehydration step away from the minor product asperlicin D (~10% of the flux). A third potential route would be transannular attack of N8 on (C4=O). That would generate a third regiosiomer, at the same mass of 406, but now with an angular 6,8,6,5 tetracyclic scaffold. The very minor product 1 with the identical mass could be this third isomer, but it was not isolable in sufficient quantity to prove structure.

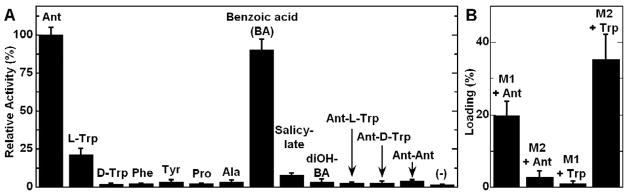

In order to gain insight into the energetics of the three different modes of cyclization, we performed quantum mechanical calculations on the free energy changes (ΔΔG) associated with each of the products shown in Figure 6 (See Computational Details in EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES). Interestingly, and as shown in Figure 7, asperlicin D is the most stable product among the three, while the structure proposed for product 1 in Figures 6 and 7 is much higher in energy. However, examination of other possible cyclization outcomes of macrocycle I suggests that this is the only reasonable option. These results suggest that not the thermodynamic stability of the three possible adducts, but kinetic factors determine the regiochemical outcome of the reaction. As also shown in Figure 7, starting from the 6,11,6-macrocycle I, different trans to cis isomerizations of the peptide bonds must take place in order to reach conformations suitable for cyclization. These are shown as macrocycles II, III, IV in Figure 7 and are appropriate for formation of asperlicin C, D, and 1, respectively. The idea here is similar to Bruice’s NAC, or “near-attack conformation” (Bruice, 2002; Bruice and Lightstone, 1999; Hur and Bruice, 2003). Macrocycle II, the corresponding transition state (TS2) leading to asperlicin C entail the most favorable pathway, while the precursors to asperlicin D are much higher in energy, consistent with the observed 10:1 ratios of asperlicin C/D (Figure 7). In view of these results, it can be hypothesized that CT domain is responsible for recognizing and stabilizing the adequate conformation of the 6,11,6-macrocycle by promoting the isomerization of the N5–C4=O peptide bond and directing the formation of asperlicin C. To what extent such nascent products are released and cyclized nonenzymatically or are cyclodehydrated on the way out of the active site of the CT domain of AspA is a subject for subsequent evaluation.

Figure 7.

Structures and relative energies calculated for the different conformations of the initial macrocycle, cyclization transition states and final dehydrated products relevant to the biosynthesis of asperlicin C, D and 1. The calculations were performed at the PCM(water)/B3LYP/6-31G(d) level using reduced models in which the indole ring from Trp side chain has been replaced by a methyl group. Amide bonds subjected to isomerization from trans to cis orientation prior to cyclization are marked in blue. Relative free energies are in kcal mol−1 and distances in Angstroms.

We note that an alternate route of intramolecular release of an Ant-Ant-L-Trp- S-T2 could be imagined, via formation of an anthranilyl-diketopiperazine. This would involve amide N5 attack (from the Ant2 residue) on the tripeptidyl thioester carbonyl (C11=O) as the chain release step (Figure 6B). Whether that amide would be a kinetically competent nucleophile compared to the Ant1 free NH2 groups seems less likely. Moreover, while that putative diketopiperazine (DKP) could then undergo cyclization and dehydration to asperlicin C, it has the wrong connectivity to get to the observed asperlicin D framework, as noted in Figure 6B. Thus, the DKP release route is ruled out and formation of the 6,11,6-tricyclic macrocycle I seems the likely mechanism of AspA.

Discussion

Our initial identification of the aspABC gene cluster(Haynes, et al., 2012) by sequencing of the A. alliaceus genome relied on gene knockouts of aspA and aspB, the NRPS- and epoxygenase-encoding genes respectively, and the accumulation of different asperlicins in extracts from those mutants. We had synthesized authentic samples of asperlicin C and asperlicin D both as standards and to evaluate their capacity to serve as substrates for purified AspB, the indole epoxygenase (Haynes, et al., 2012). Given that pure AspB acted selectively on asperlicin C (to yield asperlicin E) and not asperlicin D, we concluded that while asperlicin D was a natural Aspergillus metabolite (Liesch, et al., 1988), it was a dead end for subsequent processing to either asperlicin E or asperlicin itself. The question remained how and why asperlicin D formed as a co-product with asperlicin C.

In this study we have turned to characterization of the NRPS AspA enzyme. Bioinformatic analysis of AspA from the genome sequence predicted it would have only two modules (A1-T1-C2-A2-T2-CT) (Haynes, et al., 2012), whereas asperlicin C and D are comprised of three amino acid units, two molecules of Ant and one Trp. Thus, a question at the start of this study was whether there was an additional, as yet missing, monomodular NRPS to produce a third module, on which a tripeptidyl (Ant-Ant-L-Trp)-thioester could be tethered. Alternatively, it was possible that bimodular AspA could act twice on Ant and generate a linear tripeptidyl-S-T2 intermediate to be released by cyclizing action of the CT domain (Gao, et al., 2012).

To address whether AspA is sufficient to generate and release both asperlicin C and asperlicin D, we constructed a C-terminal His6-tagged version of the 276 kDa AspA for expression in the vacuole protease-deficient S. cerevisiae strain BJ5464-NpgA. This strain has been of use to us for cloning the comparably sized bimodular AnaPS as well as the trimodular TqaA in aszonalenin and tryptoquialanine pathways, respectively (Gao, et al., 2012). Soluble AspA with the pantetheinyl-SH prosthetic groups installed posttranslationally on T1 and T2 was thereby obtained in a yield approaching 9 mg L−1, suitable for biochemical characterization.

First, we assayed the capacity of holo AspA to activate Ant and L-Trp by reversible formation of the aminoacyl-AMPs and validated that each A domain was active. Because both A1 and A2 are contained in the same protein, one could not determine from such radioactive exchange assays if A1 was activating Ant and A2 was activating Trp, or A2 activated both Ant and Trp. To that end, the expression and separate purification of C-terminally His6-tagged M1 (A1-T1-C2) and M2(C2-A2-T2-CT) allowed that distinction. Inclusion of C2 in both constructs was necessary to achieve soluble expression of A domain containing fragments. The A1-containing protein activated Ant and the A2-containing module activated L-Trp as Trp-AMP but did not act on Ant. The two module AspA assembly line thus tethers Ant to T1 and L-Trp to T2. The Ant-Ant and Ant-Trp dipeptides were not substrates for either A1 or A2 (Figure 2A). If A1 made an Ant-Ant-tethered thioester before transferring to Trp-S-T2, one might have expected detection of the cyclic Ant-Ant dimer. No such dimer was detected from A1-T1-C2 incubations with Ant and ATP (Figure S7). Mixing the M1 and M2 reconstituted asperlicin C and D formation as efficiently as the intact AspA, proving the separate modules could function in trans, and that the second copy of the C2 domain was not a problem for reconstitution (Figure S4). M1 acts iteratively, first to generate a canonical Ant-Trp-S-T2 that is then elongated by a reloaded Ant-S-T1 to give the Ant-Ant-Trp-S-T2 as full length intermediate that undergoes release by intramolecular cyclization.

Full length, purified AspA is clearly sufficient to make the tetracyclic scaffold of asperlicin C from 2 molecules of Ant, 1 L-Trp. It also generates asperlicin D, a known A. alliaceus minor metabolite. In this study a 10:1 constant ratio of asperlicin C:D is observed by kinetic analysis as asperlicin D represents ~10% of the product flux. The constant ratio indicates both products are formed from a common intermediate or nascent product. From the failure of asperlicin D to be carried forward by AspB, the epoxygenation enzyme that takes asperlicin C on to asperlicin E (Haynes, et al., 2012), we have reasoned that asperlicin D is a dead end metabolite and so represents off pathway partitioning of a common precursor. The mixture of asperlicin C and D (and 1) are also produced in the two module reconstitution experiment as well as in the incubations with Ant-Trp-SNAC and Ant-Ant-Trp-SNAC as surrogate substrates to probe the nature of later stage intermediates during AspA catalysis. Computational analysis clearly indicated that while asperlicin D is more stable, asperlicin C is the kinetically favored product, thereby explaining the observed preference in the formation of asperlicin C from AspA. The extent to which CT domain influences the near attack conformation of the macrolactam in its active site is unclear. However, it is evident that the formation of asperlicin D cannot be suppressed under experimental conditions (both in vivo and in vitro), thereby giving support to a mechanism of transannular cyclization in which the outcomes are dictated by free energy barriers.

The AspA NRPS illustrates the unusual cyclopeptide ring sizes attainable in the asperlicin system and is distinct from the related fumiquinazoline and ardeemin systems, where comparable 6,10-bicyclic nascent products gave rise to regioisomeric tricyclic quinazolinedione scaffolds (Gao, et al., 2012) (Figure 1). In both cases we argue that the terminal CT domains are the chain release catalysts by intramolecular capture of the thioester carbonyl by the Ant1-NH2 group, yielding a 6, 10 (TqaA) or 6,11,6 (AspA) tricyclic nascent product. Subsequent closure to the very different 6,6,6-tricyclic versus 6,6,7,6-tetracyclic scaffold reflects the use of an additional Ant unit in the second position of the tripeptide framework, uniquely in the asperlicin assembly line. One planar β-amino acid unit (Ant) at the amino terminus of a tripeptidyl thioester directs cyclization to the tricyclic quinazolinedione framework. The second Ant β-aminoacyl building block adds another carbon and incorporates the fourth ring into the final asperlicin scaffolds.

While we proposed the aniline amine on the first Ant residue is responsible for initiating the macrolactam formation, there are alternative nucleophiles that may be considered to initiate the cascade of reactions. As shown in Figure S8, in addition to the possibility that the aniline nitrogen serves as the product releasing nucleophile (mechanism 3), two alternative mechanisms can be envisioned. In mechanism 1, the (C4=O) carbonyl oxygen in imide form could be sufficiently nucleophilic to first attack the thioester to generate an oxazol-5(4H)-one ring, followed by attack of the (C11=O) carbonyl oxygen and undergo ring expansion to yield a 9-membered ring, which can then be opened to the 6,11,6-macrocylce I. Alternatively in mechanism 2, the amide nitrogen bridging the two Ant residues can initiate attack on the thioester to form a 7-membered ring, followed by ring expansion to the 6,11,6-macrocycle I.

To assess the possibilities of these routes, we computed the relative free energies of each transition state and product among the three possible mechanisms (See Computational details in EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES). In order to locate and characterize transition structures for these reactions, fully deprotonated nucleophiles (both amides and anilines) were used despite the low acidities of aniline and amide groups (Figure S9) for attempts to locate neutral TS including explicit solvation and a general base. Such reactions require general base catalysis, and this is assumed to take place in the enzyme active site. The inclusion of a general base and solvent would be necessary to compute the barriers to various reactions occurring in water or the enzyme. Our calculations therefore only test the factors aside from deprotonation energetics that are required in order to distort the different intermediates along the reaction coordinate into various transition state geometries. The energetics of deprotonation of different nucleophiles by bases would be contributors to the actual free energies of reaction. As shown in Figure S8, while formation of the oxazolone product in mechanism 1 is kinetically possible (ΔΔG‡=14 kcal mol−1), it represents a thermodynamic dead-end that is unlikely to undergo additional modifications. In fact, subsequent ring expansion reactions towards either 9-membered or 7-membered rings are kinetically unfeasible (ΔΔG‡ > 35 kcal mol−1). In mechanism 2, calculations showed that the attack of the amidate nitrogen to form the 7-membered ring is highly unfavored (ΔΔG‡=34 kcal mol−1) and is therefore unlikely to take place. In contrast, the direct attack of the aniline in mechanism 3 is the favored pathway, since the activation barrier is low (ΔΔG‡=13 kcal mol−1). These results are in good agreement with the observed nonenzymatic reactivity of dipeptide Ant-L-Trp-SNAC, which undergoes fast cyclization exclusively through the terminal aniline.

In conclusion, we have focused on the mechanism of AspA-catalyzed formation of asperlicin C and D. In a prior study we showed that the monooxygenase AspB will take asperlicin C and do an oxygenative cyclization to give asperlicin E, now with a fused heptacyclic framework (Haynes, et al., 2012). This is remarkable complexity generation from a two enzyme pathway with economical strategy and catalytic execution.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning of intact aspA gene from A. alliaceus

The AspA encoding gene was assembled from six pieces (P1–P6, each ~1 to 1.5 kb) by using modified yeast-based homologous recombination methods(Gao, et al., 2012). The only intron (493–555 base pairs (bp)) in aspA gene was found by PCR with reverse transcription (RT–PCR) and no other introns were found in other regions. The assembled AspA expression plasmid was recovered from S. cerevisiae using a yeast plasmid miniprep II kit (Zymo Research) and was verified by restriction digestion and PCR. Protein expression and purification procedures are described in Supplemental Methods.

ATP-[32P]PPi exchange assay for AspA

A typical reaction mixture (500 μL) contained 1.0 μM AspA, 1 mM substrate (unless specified), 5 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Na[32P]-pyrophosphate (PPi) (~1.8 × 106 cpm mL−1), and 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). Mixtures were incubated at ambient temperature for regular time intervals (e.g., 5 min), and 150 μL aliquots were removed and quenched with 500 μL of a charcoal suspension (100 mM NaPPi, 350 mM HClO4, and 16 g L−1 charcoal). The mixtures were vortexed and centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 3 min. Pellets were washed twice with 500 μL of wash solution (100 mM NaPPi and 350 mM HClO4). Each pellet was resuspended in 500 μL wash solution and added to 10 mL Ultima Gold scintillation fluid. Charcoal-bound radioactivity was measured using a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter.

Loading of [14C]-substrate onto NRPS

A 50 μL assay mixture containing 100 mM HEPES (pH 7), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 1mM TCEP, 10 μM AspA-M1/M2, and 40 μM [14C]-labeled substrate (anthranilate or tryptophan) was incubated at ambient temperature for 30 min. The reaction was quenched by 600 μL 10% trichloroacetic acid with addition of 100 μL of 1 mg mL−1 BSA. The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 3 min. The pellet was then washed twice with 600 μL 10% trichloroacetic acid, dissolved in 250 μL formic acid, added into 10 mL Ultima Gold scintillation fluid and subjected to a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter.

Synthesis of Ant-Ant-L-Trp-SNAC

Tripeptide Ant-Ant-L-Trp was custom synthesized by GenScript USA Inc.(Piscataway, NJ). 30 mg Ant-Ant-L-Trp (1.0 eq), 140 mg PyBOP (4.0 eq), 37 mg K2CO3 (4.0 eq) and 145 μL N-acetylcysteamine (SNAC) (20 eq) were dissolved in 20 mL H2O:THF (1:1). The solution was stirred at room temperature for two hours. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo, dissolved in acetonitrile, and purified by prep-HPLC (Luna, C18 250 × 21.2mm, 10 μm, 100 Å) using a chromatographic gradient: 20–40% B, 5min; 40–80% B, 25 min; 80–100% B, 5 min (A: H2O; B: acetonitrile, 10 mL min−1, monitor at 340 nm). The peak with expected mass (m/z calculated for Ant-Ant-Trp-SNAC C29H29N5O4S [M+H]+ 544.2013, found 544.2023) was collected and lyophilized. The final yield is 19.6 mg (53%).

HPLC-Based Time Course Study of Product Formation by AspA

Master reactions (500 μL) contained 1 μM AspA, 3 mM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM amino acid substrates (Ant and L-Trp) and AspA in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) were carried out at 25 °C and 100 μL aliquots at 1, 2, 3, and 4 h time point were quenched by adding 1 mL of ethyl acetate. The initial product turnover rates were calculated with mean values ± SD. by using the data points within the linear range. The ethyl acetate layer was dried and redissolved in methanol (100 μL), and 20 μL samples were subjected to LC-MS analyses. Peak areas (at 280 nm) of the asperlicin C, aperlicin D and 1 were converted to concentrations and were used to calculate initial enzymatic rate (μM h−1).

Computational Details

Calculations were carried out with the B3LYP hybrid functional(Becke, 1993; Lee, et al., 1988) and 6-31G(d) basis set. Full geometry optimizations and transition structure (TS) searches were carried out with the Gaussian 09 package (Gaussian 09, et al., 2009). The possibility of different conformations was taken into account for all structures, and only the lowest energy structures are discussed. Frequency analyses were carried out at the same level used in the geometry optimizations, and the nature of the stationary points was determined in each case according to the appropriate number of negative eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix. The harmonic oscillator approximation in the calculation of vibration frequencies was replaced by the quasiharmonic approximation developed by Cramer and Truhlar(Ribeiro, et al., 2011). Scaled frequencies were not considered since significant errors in the calculated thermodynamic properties are not found at this theoretical level(Bauschlicher Jr, 1995; Merrick, et al., 2007). Where necessary, mass-weighted intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations were carried out by using the Gonzalez and Schlegel scheme (Gonzalez and Schlegel, 1989; Gonzalez and Schlegel, 1990) in order to ensure that the TSs indeed connected the appropriate reactants and products. Bulk solvent effects were considered implicitly by performing single-point energy calculations on the gas-phase optimized geometries, through the SMD polarizable continuum model of Cramer and Thrular(Marenich, et al., 2009) as implemented in Gaussian 09. The internally stored parameters for water were used to calculate solvation free energies (ΔGsolv).

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

Fungal peptidyl alkaloids represent a group of compounds with diverse chemical structures and important biological activities. The planar nonproteinogenic amino acid, anthranilate (Ant), is an important building block in many bioactive fungal peptidyl alkaloids. Here we heterologously expressed the bimodular NRPS AspA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and successfully reconstituted AspA to produce the regioisomers asperlicin C and D in vitro. Significantly, differing from the canonical, colinear programming rule of NRPSs, in which every module activates and appends one amino acid to the growing peptide, we showed the first module of AspA iteratively uses two molecules of Ant to build the Ant-Ant-Trp tripeptide precursor. The C-terminal condensation domain (CT) was demonstrated to cyclize the linear tripeptide and to produce a macrocycle that can undergo different intramolecular cyclization fates. Experimental and computational studies were performed to examine the regioselectivity and energetics of this step, which showed the kinetically most favored product asperlicin C dominates over the thermodynamically more stable product asperlicin D.

The bimodular NRPS AspA is heterologously expressed and reconstituted to synthesize multicyclic fungal alkaloids asperlicin C and D.

The first module of AspA iteratively activates two molecules of anthranilate (Ant), while the terminal condensation domain (CT) cyclizes the tripeptide Ant-Ant-Trp into a macrolactam which can undergo further transannular cyclization.

Computational analysis predicts kinetic factors determine the regiochemical outcome of the transannular cyclizations, which is consistent with the 10:1 ratio of asperlicin C to D observed experimentally.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Timothy A. Wencewicz is thanked for analyses of macrocyclizing mechanism and helpful discussions in synthesizing the Ant-Ant-L-Trp-SNAC substrate. Dr. Stuart W. Haynes is thanked for providing the Ant-L-Trp-SNAC substrate, and asperlicin C/D standards. We thank the National Institutes of Health for funding [GM020011, GM049338 (to C.T.W.), GM092217 (to Y.T.) and GM075962 (to K.N.H.)].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ames BD, Haynes SW, Gao X, Evans BS, Kelleher NL, Tang Y, Walsh CT. Complexity generation in fungal peptidyl alkaloid biosynthesis: oxidation of fumiquinazoline A to the heptacyclic hemiaminal fumiquinazoline C by the flavoenzyme af12070 from Aspergillus fumigatus. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8756–8769. doi: 10.1021/bi201302w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames BD, Liu X, Walsh CT. Enzymatic processing of fumiquinazoline F: a tandem oxidative-acylation strategy for the generation of multicyclic scaffolds in fungal indole alkaloid biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8564–8576. doi: 10.1021/bi1012029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames BD, Walsh CT. Anthranilate-activating modules from fungal nonribosomal peptide assembly lines. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3351–3365. doi: 10.1021/bi100198y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauschlicher CW., Jr A comparison of the accuracy of different functionals. Chem Phys Lett. 1995;246:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Becke AD. Density-functional thermochemistry. III The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- Bok JW, Hoffmeister D, Maggio-Hall LA, Murillo R, Glasner JD, Keller NP. Genomic mining for Aspergillus natural products. Chem Biol. 2006;13:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruice TC. A view at the millennium: the efficiency of enzymatic catalysis. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:139–148. doi: 10.1021/ar0001665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruice TC, Lightstone FC. Ground state and transition state contributions to the rate of intramolecular and enzymic reactions. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Chang RSL, Lotti VJ, Monaghan RL, Birnbaum J, Stapley EO, Goetz MA, Albersschonberg G, Patchett AA, Liesch JM, Hensens OD, et al. A potent nonpeptide cholecystokinin antagonist selective for peripheral-tissues isolated from Aspergillus-alliaceus. Science. 1985;230:177–179. doi: 10.1126/science.2994227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finking R, Marahiel MA. Biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:453–488. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Chooi YH, Ames BD, Wang P, Walsh CT, Tang Y. Fungal indole alkaloid biosynthesis: genetic and biochemical investigation of the tryptoquialanine pathway in Penicillium aethiopicum. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2729–2741. doi: 10.1021/ja1101085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Haynes SW, Ames BD, Wang P, Vien LP, Walsh CT, Tang Y. Cyclization of fungal nonribosomal peptides by a terminal condensation-like domain. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:823–830. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RA, Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, et al. Gaussian 09. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Schlegel HB. An improved algorithm for reaction path following. J Chem Phys. 1989;90:2154–2161. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Schlegel HB. Reaction path following in mass-weighted internal coordinates. J Chem Phys. 1990;94:5523–5527. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes SW, Ames BD, Gao X, Tang Y, Walsh CT. Unraveling terminal C-domain-mediated condensation in fungal biosynthesis of imidazoindolone metabolites. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5668–5679. doi: 10.1021/bi2004922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes SW, Gao X, Tang Y, Walsh CT. Assembly of asperlicin peptidyl alkaloids from anthranilate and tryptophan: a two-enzyme pathway generates heptacyclic scaffold complexity in asperlicin E. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:17444–17447. doi: 10.1021/ja308371z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes SW, Gao X, Tang Y, Walsh CT. Complexity generation in fungal peptidyl alkaloid biosynthesis: a two-enzyme pathway to the hexacyclic mdr export pump inhibitor ardeemin. ACS Chem Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1021/cb3006787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur S, Bruice TC. The near attack conformation approach to the study of the chorismate to prephenate reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12015–12020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534873100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karwowski JP, Jackson M, Rasmussen RR, Humphrey PE, Poddig JB, Kohl WL, Scherr MH, Kadam S, McAlpine JB. 5-n-acetylardeemin, a novel heterocyclic compound which reverses multiple-drug resistance in tumor-cells. 1 taxonomy and fermentation of the producing organism and biological-activity. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1993;46:374–379. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesch JM, Hensens OD, Zink DL, Goetz MA. Novel cholecystokinin antagonists from Aspergillus alliaceus II Structure determination of asperlicins B, C, D, and E. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1988;41:878–881. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linne U, Marahiel MA. Reactions catalyzed by mature and recombinant nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Protein Eng. 2004;388:293–315. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)88024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma SM, Li JW, Choi JW, Zhou H, Lee KK, Moorthie VA, Xie X, Kealey JT, Da Silva NA, Vederas JC, et al. Complete reconstitution of a highly reducing iterative polyketide synthase. Science. 2009;326:589–592. doi: 10.1126/science.1175602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:6378–6396. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick JP, Moran D, Radom L. An evaluation of harmonic vibrational frequency scale factors. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:11683–11700. doi: 10.1021/jp073974n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadri LEN, Weinreb PH, Lei M, Nakano MM, Zuber P, Walsh CT. Characterization of Sfp, a Bacillus subtilis phosphopantetheinyl transferase for peptidyl carrier protein domains in peptide synthetases. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1585–1595. doi: 10.1021/bi9719861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro RF, Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. Use of solution-phase vibrational frequencies in continuum models for the free energy of solvation. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:14556–14562. doi: 10.1021/jp205508z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez JF, Somoza AD, Keller NP, Wang CCC. Advances in Aspergillus secondary metabolite research in the post-genomic era. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:351–371. doi: 10.1039/c2np00084a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattely ES, Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Total biosynthesis: in vitro reconstitution of polyketide and nonribosomal peptide pathways. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:757–793. doi: 10.1039/b801747f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi C, Matsushita T, Doi M, Minoura K, Shingu T, Kumeda Y, Numata A. Fumiquinazolines A-G, novel metabolites of a fungus separated from a pseudolabrus marine fish. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1995;1:2345–2353. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CT, Haynes SW, Ames BD. Aminobenzoates as building blocks for natural product assembly lines. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:37–59. doi: 10.1039/c1np00072a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CT, Haynes SW, Ames BD, Gao X, Tang Y. Short pathways to complexity generation: fungal peptidyl alkaloid multicyclic scaffolds from anthranilate building blocks. ACS Chem Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1021/cb4001684. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin WB, Grundmann A, Cheng J, Li SM. Acetylaszonalenin biosynthesis in Neosartorya fischeri identification of the biosynthetic gene cluster by genomic mining and functional proof of the genes by biochemical investigation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:100–109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.