Abstract

Electrospray ionization (ESI) is an important tool in chemical and biochemical survey and targeted analysis in many applications. For chemical detection and identification electrospray is usually used with mass spectrometry (MS). However, for screening and monitoring of chemicals of interest in light, low power field-deployable instrumentation, an alternative detection technology with chemical selectivity would be highly useful, especially since small, lightweight, chip-based gas and liquid chromatographic technologies are being developed. Our initial list of applications requiring portable instruments includes chemical surveys on Mars, medical diagnostics based on metabolites in biological samples, and water quality analysis. In this report, we evaluate ESI-Differential Mobility Spectrometry (DMS) as a compact, low-power alternative to MS detection. Use of DMS for chemically-selective detection of ESI suffers in comparison with mass spectrometry because portable MS peak capacity is greater than that of DMS by 10X or more, but the development of light, fast chip chromatography offers compensating resolution. Standalone DMS provides the chemical selectivity familiar from DMS-MS publications, and exploits the sensitivity of ion detection. We find that sub-microliter-per-minute flows and a correctly-designed interface prepare a desolvated ion stream that enables DMS to act as an effective ion filter. Results for a several small organic biomarkers and metabolites, including citric acid, azelaic acid, n-hexanoylglycine, thymidine, and caffeine, as well as compounds such as dinitrotoluene and others, have been characterized and demonstrate selective detection. Water-quality-related halogen-containing anions, fluoride through bromate, contained in liquid samples are also isolated by DMS. A reaction-chamber interface is highlighted as most practical for portable ESI-DMS instrumentation.

Keywords: ion mobility, nanospray, electrospray, differential ion mobility, DMS, FAIMS

Introduction

Instrumentation for chemical analysis is essential for many scientific, environmental and clinical applications but the range of tools available for field deployment is limited. For high sensitivity and selectivity, mass spectrometry (MS) is often the method of choice, while optical spectroscopy is competitive in selectivity, but cannot equal MS sensitivity. The detection of ion signals, as in mass spectrometry, is highly sensitive and electrospray ionization (ESI) is efficient at broad-spectrum ionization from liquid samples with little fragmentation. Chemical selectivity can be provided by a back-end mass spectrometer, but at a cost of added power consumption, and increased weight and cost, although progress continues to be made in reducing that burden (Ouyang and Cooks 2009; Gao et al. 2008; Gao et al. 2010; Cooks et al. 2009; Xu et al. 2010).

As chip-based liquid chromatography (LC) systems with integrated trap, column, and emitter operating at nano-flow levels become available (Brennen et al. 2007; Grimm et al. 2005; Ghitun et al. 2008; Bynum et al. 2010), new field-deployable devices should combine components of similarly reduced physical and electrical parameters and sufficient chemical selectivity. We have tested differential mobility ion separation with ion current detection (DMS) as a more compact alternative to MS detection. DMS provides selectivity and chemical noise suppression that can be used with low-flow ESI sources such as chip-LC with integrated emitter.

Our intended applications for portable instruments include chemical analysis on Mars and other planetary environments, medical diagnostics based on metabolites in a biological matrix such as urine, and water quality analysis, all of which can benefit from improved instrumentation. Gas chromatography (GC)-DMS has already been applied by NASA in Air Quality Monitoring on the International Space Station, with excellent results reported by Limero et al. (Limero et al. 2012). We want to extend DMS technology to the broader range of targets accessible through ESI.

Ion mobility is well known as a method of separating ions by size, charge, conformation, polarity, and other physical, chemical, and electrical properties. The ion mobility group of techniques is used for ion separation in two primary forms. The first is a low mobility separation in drift-time ion mobility spectrometry (DT-IMS) or in traveling-wave ion mobility (TW-IMS) (generically, IMS). The second form depends on the field-dependence of ion mobility, and is known as differential mobility spectrometry (DMS), or field-asymmetric ion mobility spectrometry (FAIMS), or ion-mobility-increment spectrometry (IMIS), here generically DMS. Ion mobility is used in standalone form and in combination with other selective detection methods, especially mass spectrometry. Both ion mobility and differential ion mobility have been described from historical and technical perspectives in monographs (Eiceman and Karpas 2005; Shvartsburg 2008), and technical improvements and new applications and reviews (Lapthorn et al. 2013) appear regularly in the literature.

Ion mobility techniques are capable of operating with almost any atmospheric-pressure ionization source, and can easily be used with standard LC technology. As a fast ion selector or as a detector for fast chromatography, DMS generally has several useful properties, as summarized here, and detailed elsewhere (Coy et al. 2010; Krylov 2003; Shvartsburg et al. 2006).

Continuous operation. DMS operates in continuous mode as an ion filter while IMS methods intermittently gate ions into the mobility cell for analysis, resulting in either lower sensitivity due to ion gate losses, the extra complexity of an intermediate ion trap (Pringle et al. 2007; Kanu et al. 2008b) or the use of the Hadamard transform(Belov et al. 2008).

Low loss. The planar configuration for DMS has a loss profile that is efficient and essentially independent of ion mobility coefficient(Krylov 2003). In a commercial implementation, ion losses have been shown to be on the order of 20% under low flow conditions (Schneider et al. 2010a). In the prototype designs appropriate for small instruments tested here, the transmission coefficient is typically about 20%.

High speed. DMS operates at atmospheric pressure for high speed and resolution, with transit time delays on the order of 10 msec.

Modifier-enhanced resolution. Addition of low concentrations of polar modifiers to the drift (IMS) or transport (DMS) gas increases selectivity by chemically-specific ion-neutral clustering (Levin et al. 2006; Krylov and Nazarov 2009; Schneider et al. 2010b; Rorrer and Yost 2011; Tsai et al. 2012). Modifiers also suppress interfering species and clusters with lower proton affinity (positive mode) or electron affinity (negative mode) than the target analyte through charge competition (Schneider et al. 2012; Schneider et al. 2010b; Hall et al. 2012; Levin et al. 2007; Levin et al. 2006). Similar effects are familiar IMS (Dwivedi et al. 2006).

Adapted to small molecules. DMS techniques have optimum performance for small molecular weight compounds, as in our intended applications. DMS selectivity typically decreases with molecular weight, while IMS is more selective for higher masses.

In this communication, planar DMS is employed in small-molecule, low-flow electrospray applications. Ion mobility in lab-scale mass spectrometry, as in the AB SCIEX SelexION or Waters Synapt systems, is designed without regard to gas flows, heater power consumption, and complexity (for instance, the AB SCIEX ion source may use desolvation temperatures as high at 750°C). Our goal in this work is to characterize ESI-DMS as a simplified miniature electrospray detector that provides an extra level of resolution for infused samples or for a nano-flow chip-LC system. As mentioned, our intended applications include astrobiology (traces of life, including amino acids and peptides (NASA Astrobiology: Life in the Universe 2012) ), metabolic biomarker detection (Coy et al. 2011b; Coy et al. 2010), as well as environmental monitoring.

A comparison of the power and weight characteristics of portable mass spectrometers, and an ESI-DMS system, shown in Table 1, indicates that the ESI-DMS system can be very much lighter and lower in power than MS systems, but with lower peak capacity. Except in special cases, additional methods like chromatography may be necessary, but that is often necessary in MS applications as well.

DMS selectivity

The ion separations used in differential mobility spectrometry (DMS) are determined by the differential mobility parameter, α(E), which describes the relative change with electric field amplitude of the ion mobility coefficient (Buryakov et al. 1993), K(E):

| (1) |

v(E) is the field-induced ion drift speed, E the electric field strength, N the buffer gas density, and ETd is E/N, which is the ion mobility field in Townsend units (Nazarov et al. 2006b). The mobility coefficient, K(E), acquires a dependence on field strength that is dependent on properties of the ion (Mason and McDaniel 1988), interactions of the ion with its chemical environment (Krylov and Nazarov 2009; Schneider et al. 2010b; Levin et al. 2006), and the pressure, and temperature in the DMS analytical region (Nazarov et al. 2006b; Krylov et al. 2009). This field dependence is dominated by ion-neutral chemical affinity (except in the case of helium transport gas), which is the basis of the high small-molecule selectivity of DMS.

The ion mobility coefficient in Townsend units, NK(E), can be written in terms of an effective cross-section for the interaction of the ion with all the neutrals in the local chemical environment.

| (2) |

The quantities in square brackets ([]) can be disregarded in a qualitative view because they are constant at a particular bulk gas temperature, T, and independent of the ion for heavier ions. Thus, all the variation in ion mobility in Townsend units, NK(E), is contained in the ion-neutral cross-section, Ω, controlled by the effective temperature, Teff. Other symbols in the equation have their usual meanings. The effective temperature, Teff, is the bulk gas temperature, T, plus a heating term from the applied field, ςm (K (E )E )2/3k (Krylov et al. 2009) (ζ is an ion-specific parameter, typically 0.5 to 1.0). From the above expression for ion mobility, it can be concluded that temperature and pressure have only weak effects on practical DMS resolution, but that modifiers, which decluster synchronously with the DMS waveform, can increase differential mobility by modulating the cross-section. The dissociation of ion-neutral clusters is required for the highest field dependence and thus the highest DMS selectivity and that can be facilitated by lower pressure and higher temperature. In the case of Mars, since the ambient pressure is 4.56 torr, clusters will be reduced, and ESI at low pressure has been developed in the Smith group at PNNL (Page et al. 2008).

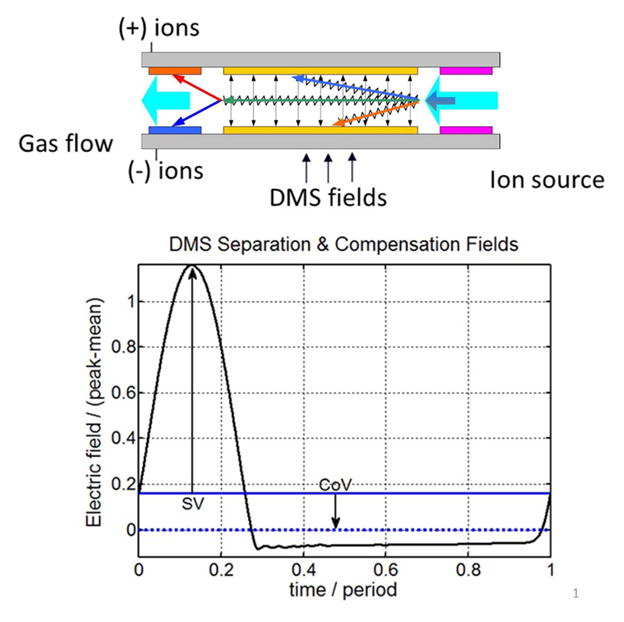

The configuration of a DMS system with integrated detectors is shown in Figure 1. The fields applied in the DMS region are also shown. The separation voltage / field (SV) is an AC waveform (time average zero) and the compensation voltage (CoV) is a DC offset that tunes the waveform trajectory to pass selected ions. The waveform properties and generation are discussed in more detail in (Krylov et al. 2010). The DMS filtration process is specified by these two electrical parameters, SV, and CoV, in addition to environmental variables pressure, temperature, and transport gas composition.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the DMS analytical region and notation for the waveform used in these experiments. The DMS ion filter is a simple planar region (typ. 0.5 mm gap, 10. mm length, 3 mm width, 300–600 ccm flow) with Faraday plate ion detection. The field applied across the channel is of the “flyback” type, with a period of 800 nsec. The solid horizontal line is the waveform time-average. DMS separation field (SV) is measured as waveform mean to peak voltage (SV), and compensation field (CoV) is measured as mean voltage difference.

Peak capacity in DMS has been discussed in a recent publication by Schneider et al. (Schneider et al. 2012) and in a data-rich Pittcon presentation available from the AB-SCIEX web-site (Schneider and Covey 2012). As shown in those works, peak capacity without chemical modifiers is typically on the order of 20, and about 40 or higher with modifiers.

Experimental

Chemicals

Electrospray solvents, acetonitrile, methanol, and water were Fisher Scientific Optima LC/MS grade. Other chemicals include thymidine (C10H14N2O5, MW = 242.09027, CAS 50-89-5) from Alfa Aesar (L12490), azelaic acid (C9H16O4, MW = 188.10485 CAS 123-99-9) from Alfa Aesar (36308), Citric acid monohydrate (C6H8O7, MW = 192.027 CAS 77-92-6) from Alfa Aesar (22869), n-hexanoylglycine (C8H15NO3, MW = 173.10519 CAS 24003-67-6), from Dr. Herman J. ten Brink, VU Medical Center Metabolic Laboratory, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, including caffeine, formic acid, ammonium acetate, DL-trisodium isocitrate, and 2,4-dinitrotoluene. Anion solutions for fluoride, chloride, and bromate were provided in the form of ion-chromatography test solutions by Dionex as ion standard solutions (www.dionex.com).

ESI interface to DMS

Compact instrumentation designs are constrained by available power, gas flow rates, and size requirements. We have considered three interface types: (1) Curtain gas: a fully-desolvating curtain-gas interface with ions desolvated in a hot gas counter-flow, (2) Reaction chamber: a reaction / desolvation chamber design with hot-gas dilution, and (3) Capillary or skimmer: a heated capillary or simple orifice design with thermal declustering only. The three configurations are briefly described below.

Curtain-gas interface

The fully-desolvating curtain-gas interface used in commercial lab-scale instrumentation is illustrated in Figure 6 in Schneider et al. (Schneider et al. 2010c). In this design, ions travel from the ESI source through a curtain-plate outflow of hot gas. The DMS interface behind the curtain plate is maintained at a mean attractive potential difference of about 1000 V, so that ions are pulled through the hot clean curtain gas toward the DMS interface. At the DMS entrance, ion flow merges with gas being aspirated into the mass spectrometer and passes through the DMS ion filter (Schneider et al. 2010b). Similar counter-flow is also used in drift-time ion mobility spectrometry (IMS)(Kanu et al. 2008a). In both DMS (Levin et al. 2007; Schneider et al. 2012) and IMS (Dwivedi et al. 2006), modifiers can be added to the curtain gas for greater specificity. Because the curtain gas design requires high flows of purified gas and higher heater power, we have not further considered it for portable applications. This design is in commercial use by AB SCIEX both with and without DMS. .

Reaction chamber

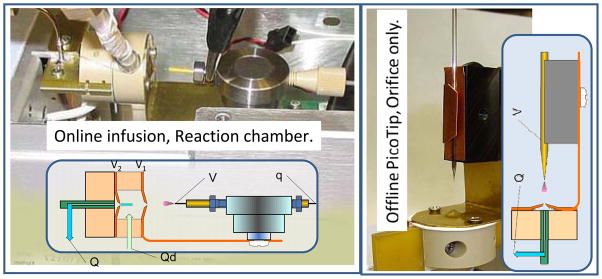

The reaction chamber interface is simpler to implement, requires lower gas flows, and uses lower voltages on the interface than the curtain gas system. Rather than supplying a flow exceeding the transport flow of the DMS, dilution with a 10–20% flow of heated gas, which may contain modifier, is used. This design is illustrated in Figure 2 (left). Pre- and post- reaction-chamber orifices reduce the entry of droplets, and the reaction chamber allows additional time for heating and desolvation of the electrospray plume, and the equilibration of charge-transfer and modifier-clustering reactions. An attractive potential of 40 to 400 V is applied between the reaction chamber orifice and a similar orifice at the DMS entrance. DMS SV and CoV values for ion transmission in this system are modified by ESI solvent vapors, and the additional concentration of any added modifiers. Room air provides the bulk of the gas flow, which may add trace contaminants extracted in the reaction chamber, but that effect is minimized by the short emitter-to-orifice distance, and they are usually removed by DMS filtration. In difficult environments, chemical filter cartridges may be used to purify the desolvation gas and to supply an electrospray chamber.

Figure 2.

Two configurations have been tested which are suitable for field-portable instrumentation. The system at left uses a reaction chamber for ion desolvation. In the reaction chamber design, total gas flow, Q (400–800 sccm) includes a heated desolvation and modifier gas flow, Qd, of about 100 sccm at about 100°C, with the balance of gas aspirated from the ESI plume region. The ESI liquid infusion, q, is 50–600 nL/min, with an emitter voltage drop V-V1 in the ±1400–2000 V range for Proxeon metal emitter tips. The voltage across the reaction chamber, V2-V1 (not critical) is typically ±40 to 100 V, and V2 is set to the mean DMS potential. At right is shown the configuration with very low flow and no additional desolvation. The reaction chamber allows more complete breakup of ion-solvent clusters, provides more stable intensities, and works at higher liquid flows. A full curtain-gas system (Qd > Q, for net outflow toward the ESI source for complete control of desolvation and modifier effects) is not discussed here, but is used in the AB SCIEX commercial DMS-MS and is shown in Schneider et al (2010a)..

Simple orifice or heated capillary

Use of an entry orifice with low nano-flow is the simplest of the three designs, with no added desolvation gas or region (Figure 2, right). A heated tube 0.8 mm ID or smaller can also be used with similar performance. Heating in the tube is used for desolvation, and emitter approach angle and distance aid in the separation of solvent droplets and clusters in both cases. This method is less effective because the ESI solvent vapors remain undiluted. Since equilibration time is short, evaporative cooling can fight desolvation. However, the presence of solvent vapors improves DMS resolution through the modifier effect, but only on the desolvated fraction of ions since the modulation of ion mobility depends on the ratio of clustered and unclustered molecular sizes. Testing described below indicate that this design is less effective than might be expected, even at the lowest flows because of instability in the droplet fraction and the tendency to deposit charges on inlet surfaces which decrease ion flow.

Equipment

Electronics for generation of DMS voltages, detection of DMS ion currents, and serial communication with a controlling PC were derived from components from a Sionex Corp. SVAC microDMx system (Krylov et al. 2009; Nazarov et al. 2006a). The electronics provide the fly-back DMS waveform shown in Figure 1, with peak-to-mean separation voltage (SV) amplitude from 500 V to 1500 V for DMS-filter mode and 0 V for DMS transparent mode (SV = 0 V), and compensation voltage (CoV) ranging from −43 V to +15 V. The dual detection circuits for positive and negative ions have gains of 166 pA/V, bandwidth of 15 kHz, and RMS noise below 1 mV in 10 msec averaging time. The system was operated, and data was acquired using Sionex Expert software, and data analysis done in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA).

In the two experimental configurations shown in Figure 2, gas flows from 300 to 600 sccm are used. The DMS analytical region is (0.5 mm H, 3.0 mm W, 10 mm L). DMS resolution can be shown to be proportional to the height dimension at constant diffusion loss (Krylov 2012), but practical sensor design is limited by available gas flow rate and electrical breakdown field. Waveform shapes are described in more detail elsewhere (Krylov et al. 2010). We employ a frequency of approximately 1.25 MHz (800 nsec period) for the asymmetric waveform. For an ion mobility of K = 1.5 cm2/(V·sec), the predicted loss due to diffusion at 300 K, 1 atm., is 30% (SV = 0), increasing to 35% with SV = 100 Td (1223 V), with a predicted transmission peak width of 1.1 V (CoV), based on a custom MATLAB application containing DMS design principles.

The three sections of the sensor, desolvation / reaction chamber (if any), DMS analytical region holder, and detection region holder were machined from PEEK, while the electrodes of the DMS analytical and detector regions were manufactured as gold-metal traces on alumina ceramic or on circuit board. Nitrogen or air, dried through an Ailtech Hydropurge cartridge, was provided for desolvation and modifier introduction, with the desolvation gas heated to ~90°C by passage through a 4″ long, 1/16″ stainless tube wrapped with a heating element (~4 W). Total DMS transport gas flow was controlled at the sensor outlet by a needle valve connected to a micro KNF diaphragm pump or to a vacuum source. Data for comparison with DMS-MS acquired on an AB SCIEX API 3000 with a prototype DMS curtain-gas interface, and a nebulized micro-spray ESI source with Proxeon ES563 emitter. This data is not shown, but had similar DMS characteristics.

Infused sample was delivered at flow rates from 20 to 800 nL/min by a Harvard Apparatus Syringe pump with Hamilton gas-tight syringes of 10 μL and 25 μL sizes. Stainless steel emitters from Proxeon (ES561, www.proxeon.com) were used, as well as off-line Econo12 PicoTip emitters from New Objective (www.newobjective.com).

Results and Discussion

Metabolic biomarker analysis

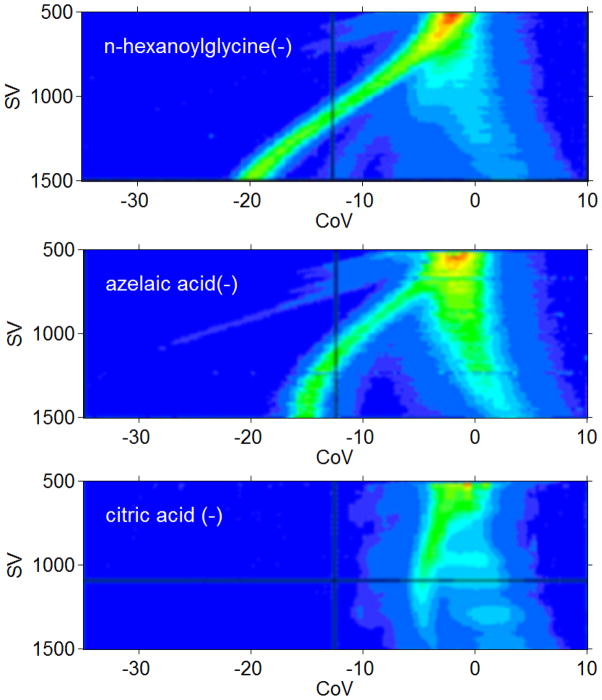

A reaction chamber interface shown in Figure 2 (left) was used to record the DMS-detected negative ion electrospray of several small organic molecules, including azelaic acid ([M-H]−, −187.097), n-hexanoylglycine ([M-H]−, −172.097), citric acid([M-H]−, −191.019), DL-isocitric acid([M-H]−, −191.019), and thymidine([M-H]−, −241.082). Topographic or dispersion 2-D plots (Figure 3) show the complete DMS-detected transmission profile for all SV and CoV for three of these compounds (n-hexanoylglycine, azelaic acid, and citric acid). These molecules have previously been identified as candidate urinary biomarkers for radiation exposure (Tyburski et al. 2008), and are associated with stress response. Each compound was prepared in 50/50 methanol/water at 100 μM, and was supplied at 500 nL/min to a Proxeon ES561 emitter at −1.7 kV. DMS total transport gas flow was 0.6 LPM, and desolvation flow was 0.1 LPM dry nitrogen heated to approximately 100°C.

Figure 3.

ESI-DMS of three reported urine biomarkers of radiation exposure are shown across the entire DMS tuning range in these topographic or dispersion plots. N-hexanoylglycine, azelaic acid, and citric acid are shown in (−). It is adventageous to use negative ion mode for biological samples. In positive mode, ion concentrations are diluted by the occurence of Na and K adducts, by proton and Na-bound dimers, and by the more facile proton attachment of matrix ions. These ions are successfully resolved, but a gas-phase modifier or liquid chromatography will be necessary to resolve other targets. (See next two figures.)

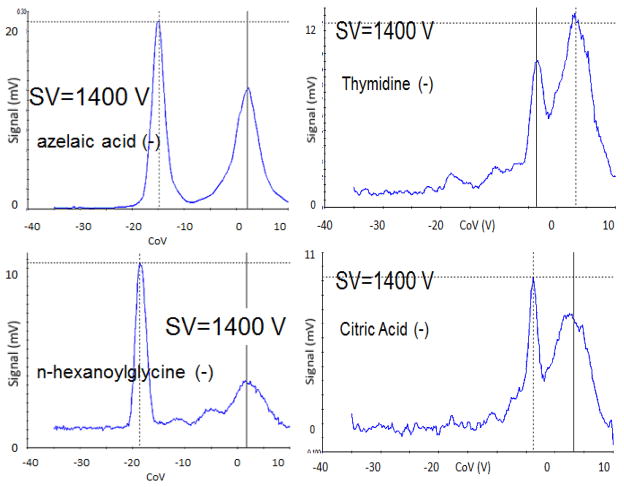

All of the compounds can be detected as deprotonated anions at specific DMS SV/CoV. Negative ion mode is usually preferred for detection of polar urine biomarkers in biological matrices because fewer interferents appear in negative electrospray than in positive. Positive ion mode has additional complexity from Na and K adducts as well as proton or Na-bound dimers, and a number of less polar compounds attach a proton (PA) but have low electron affinity (EA). Figure 4 shows DMS signals as a function of compensation voltage for azelaic acid, n-hexanoylglycine, thymidine, and citric acid at SV 1400 V. The signals for azelaic acid and n-hexnoylglycine can be resolved from the remaining ion-solvent cluster peak near zero CoV at the highest voltages. The background peak is a bit large in these data, and may be due to two effects: excessive concentration (100 uM) leading to dimer ions, and relatively high liquid flow and low desolvation flow. Compensation voltages, −15 V for azelaic acid, and −19 V for n-hexanoylglycine at 1400 V SV are quite distinct, but peaks for thymidine and citric acid are at the same CoV. If used with LC, this is not a problem since the polar citric acid and the relatively non-polar thymidine would be separated. However, it has been found in previous DMS-MS work that citric acid is shifted by isopropanol modifier, while thymidine is little affected. Isocitrate was also found to have a DMS profile very close to citrate anion in previous DMS-MS work, but the two anions could be resolved by the addition of a small amount of 1,2,3-trichloropropane modifier in the transport gas (Coy et al. 2010). The utility of modifiers in ESI-DMS is discussed in the next section.

Figure 4.

Radiation-exposure biomarkers thymidine and citrate are not resolved under the conditions of Figure 3 although azelaic acid and n-hexanoylglycine are. Citric acid is shifted to more negative compensation voltage by alcohol gas-phase modifiers while thymidine is not (DMS-MS data, not shown), thereby allowing them to be resolved. Examples of modifier effects are shown in Figure 5.

ESI-DMS modifier-enhanced resolution

The use of modifiers in the transport gas stream to increase the DMS field modulation of the effective cross-section has been described in a number of publications (Levin et al. 2006; Schneider et al. 2010b; Schneider et al. 2012). We illustrate this method in ESI-DMS with the most generically-effective modifier for positive ions, isopropanol (other alcohols are also effective). For negative ions, methylene chloride is often used, and 1,2,3-trichloropropane has been found to be especially effective, even at low concentrations.

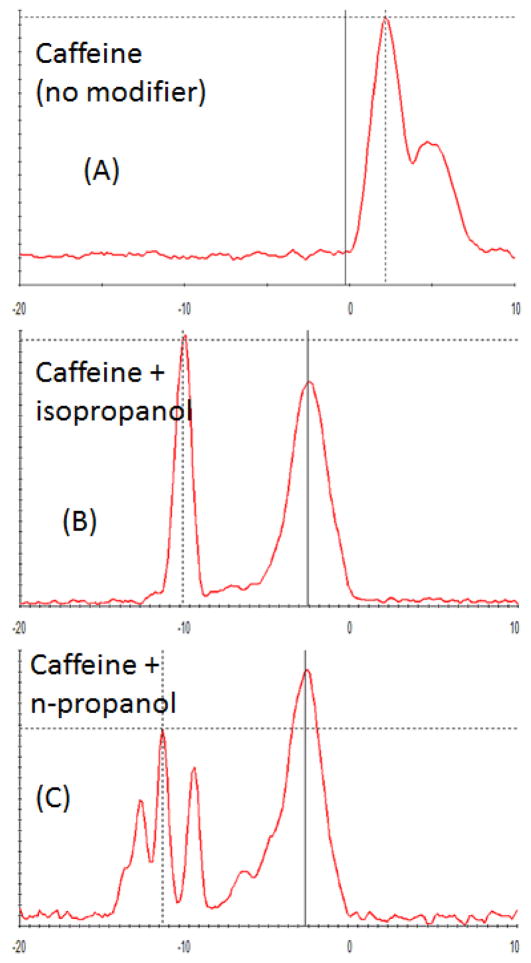

ESI-DMS in positive ion mode was tested for caffeine with and without transport gas modifiers. Modifiers isopropyl alcohol, and n-propyl alcohol were introduced at about 1% by volume with the desolvation flow in the reaction chamber. These results are shown in Figure 5. For caffeine in Figure 5 (A), at the maximum SV of 1500 V, the caffeine peak is only partially separated from the cluster peak, but could be used for detection in combination with LC with a stable solvent background level. Figures 5 (B) and 5 (C) show that the addition of alcohol modifiers isopropyl alcohol or n-propyl alcohol provide much higher resolution at lower SV (650 V). The caffeine sample was 100 μM in 50/50 acetonitrile/water, and the infusion rate 300 nL/min.

Figure 5.

Caffeine is used here to illustrate modifier-enhanced DMS resolution in reaction-chamber DMS. Peaks are shifted and separated by the introduction of about 1% v/v isopropanol or n-propanol in the transport gas stream in the reaction chamber. The caffeine concentration (100 uM) is large, resulting in a significant cluster peak (rightmost peak). (A) no modifier, (B) 1% isopropanol, (C) 1% n-propanol. The multiple peaks with n-propanol may indicate multiple conformations.

The multiple caffeine peaks for n-PA may indicate multiple cluster structures or multiple cluster numbers. The mechanism, kinetics, and thermochemistry of DMS modifier effects have been considered briefly in earlier publications (Levin et al. 2007) (Krylov and Nazarov 2009), but a number of mechanistic, kinetic, and thermochemical questions remain on the modifier effect. Molecular and cluster structures have been calculated, as well as entropy and enthalpy values for correlation with DMS behavior, and work is ongoing.

Water quality: Halogen-containing anions

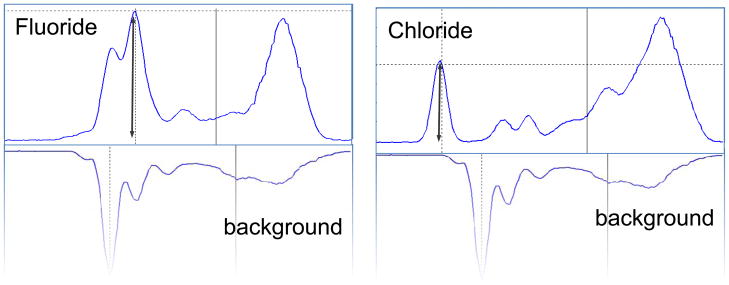

We have also tested DMS-detected electrospray for ion chromatography detection for common anions, fluoride, chloride, bromate, formate, and acetate. This kind of analysis is essential in the monitoring of water contaminants for industrial and public health applications. Some of these results are shown in Figure 6, comparing chloride and fluoride with the solvent background. Fluoride anion was identified by DMS-MS as the hydrated fluoride anion, F−(H2O), m/z= −37, while chloride is carried by Cl−, m/z=37 and 35. Table 2 lists DMS characteristics of several other species important for water quality, such as BrO3−, generated in water treatment. The estimated LOD for chloride and fluoride was computed as 100 ppb based on the observed S/N in a survey scan with 10 msec averaging time. Many volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in water have previously been detected using GC-DMS (Sionex data, not shown), and should similarly be observable in ESI-DMS. The use of reclaimed and recycled water in environments with limited storage space and no continuous water supply, such as the International Space Station, has many advantages but requires broad-spectrum monitoring of contaminants.

Figure 6.

ESI-DMS of water samples of fluoride (H2O)F− and chloride (Cl−) (10 ppm) compared to solvent background (50/50 ACN/water) in the offline nanospray-DMS orifice system of Figure 2. Additional results are shown in Table 2. The rightmost peak in each case is a dimer and solvent cluster peak that would be decreased with heated reaction chamber desolvation and lower concentrations.

Table 2.

Experimental results for halogen anions important for water quality. Samples concentrations were in the 1–10 ppm range, diluted in 50/50 acetonitrile / water. Bromate (BrO3−) is a common result of water treatment. Ion identities were determined by DMS-MS. Formate occurs as an anion and a proton-bound dimer. Acetate is not distinguished from ACN under these conditions. Data was taken on the offline emitter system without additional desolvation of Figure 2 (left). This results in some signal instability that is avoided in the reaction chamber design.

| Sample | Ion | CoV(500 V SV) | CoV(550 V SV) | CoV(600 V SV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloride | Cl− | −15.5 V | −20.2 V | weak |

| Fluoride | (H2O)F− | −10.6 V | −16.9 V | |

| Bromate | BrO3− | −3 V | −4.8 V | |

| Formate | CHO2−, ((CHO2)2H)− | −12 V, −4.4 V | ||

| Acetate | −12.3 V | −19.5 V | ||

| ACN/water only | CH3CN− | −12.3 V | −19.5 V |

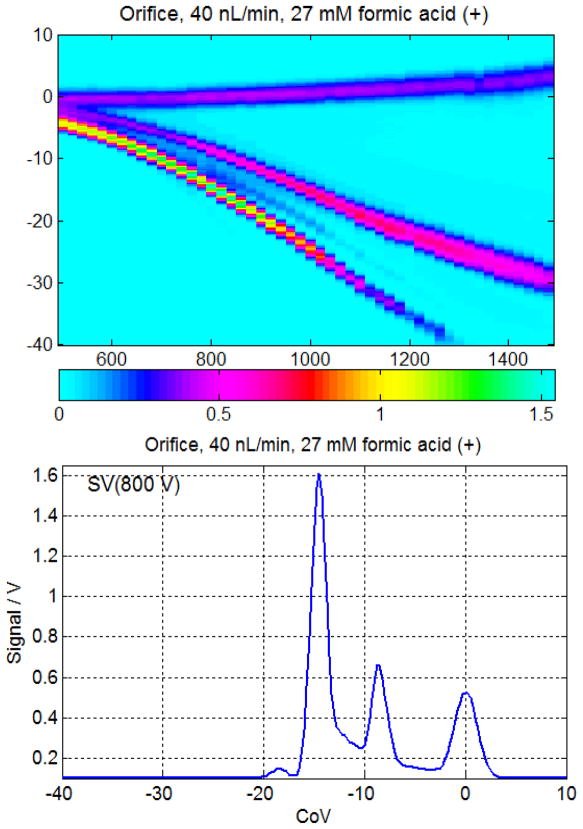

Simple Orifice / Capillary interface: ESI-DMS signal stability

Ion streams generated by ESI are monopolar and can be intense. ESI may be contrasted with the bipolar ion stream generated by some other sources, such as radioactive ionization (such as 63Ni) and UV photoionization. In DMS, contact of the ions with the walls of the analytical region is part of the selectivity of the system, allowing only one ion species to pass out of the DMS analytical region un-neutralized. This characteristic can lead to charge buildup, even on metal surfaces (as is familiar in vacuum in mass spectrometry under heavy ion loads). This charge buildup can lead to intensity changes, or even to transmission pinch-off. As indicated in Table 3, this effect is greatest in systems without a desolvation gas stream. A DMS system with a simple orifice sample introduction has the least ion losses and the greatest signal levels but is prone to charge buildup and loss of intensity. The large signals are illustrated by the signals over a volt in amplitude, corresponding to nearly 250 pA of ion current in a system with a noise floor on the order of 0.1 pA with 10 msec averaging time (Figure 7). Introducing too many ions into an inlet without desolvation leads to enormous signals followed by amplitude instability and, finally, complete loss of ion transmission.

Table 3.

Immediate ion desolvation at atmospheric pressure is more important for DMS than for MS because expansion to vacuum is strongly desolvating. These three designs are discussed in the text, with results summarized here. Although the curtain gas interface is most effective, the reaction chamber design is effective with lower gas flows, and provides some modifier-effect resolution enhancement. The simplest heated capillary / orifice interface can be used at flows from 20 to 80 nL/min, but is still occasionally unstable.

| Desolvation method | Flow Ratio desolvation / DMS | liquid flow | modifier effect from ESI solvent | Intensity instability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curtain gas | 1.0 to 2.0 | < 20 uL/min | No | None |

| Reaction chamber | 0.1 to 0.5 | < 600 nL/min | Yes | occasional |

| capillary or orifice, no reaction chamber | No added flow | < 80 nL/min | Yes | frequent, esp. for orifice. |

Figure 7.

Nanoflow with orifice interface can provide very large signals, but is weak in desolvation and prone to instability. The bottom trace show ~250 nA peak (166 pA/V gain) at SV 800 V. The S/N exceeds 2000:1 averaged 10 msec per point (27 mM formic acid in MeOH/water, 40 nL/min). Without the reaction chamber heated desolvation gas, charge buildup and ion flow pinch-off can result, preventing ion transmission. A low-flow online infusion system was used for these results.

Conclusions

General guidelines for the three interface types that we have described (curtain gas, reaction chamber, and capillary or skimmer) are given in Table 3. The higher liquid flows require the more effective desolvation methods. The efficiency values given for the curtain gas interface on lab-scale DMS-MS systems (SelexION, AB SCIEX) are generally consistent with the results for DMS losses observed in Schneider et al.(Schneider et al. 2010a). The reaction chamber interface is clearly the most practical for use in NASA applications and for other portable applications, due to acceptable performance and modest flow requirements. The capillary or skimmer interface can be used effectively only for offline disposable emitter applications, but this method is the most economical in sample usage and among the highest in ionization efficiency. A simple interface of the latter type was used in recent work in the Cooks group at Purdue on interfacing DMS to a small ion trap mass spectrometer with discontinuous sample introduction (Tadjimukhamedov et al. 2010); it is likely that a reaction chamber or curtain gas interface could improve the performance and flexibility of DMS interfaces to this type of device, as it does for independent DMS detection.

We conclude that a heated reaction chamber is the minimum needed for desolvation and stability of chemical effects. A simple orifice is not effective, even at very low nano-flows in the range of 20–80 nL/min. A heated tube without reaction chamber under similar conditions was also found to give approximately the same behavior. Problems with the use of a small tube for desolvation prior to DMS at near atmospheric pressure do not imply any difficulty with a heated capillary in the atmosphere to vacuum transition common on Thermo Scientific instruments, which is effective due to expansion into low pressure. The reaction chamber design is lower in ion transmission than a full curtain gas interface (15–20%) (Hall et al. accepted; Kafle et al. accepted) versus 60–80% at low flow (Schneider et al. 2010a), but requires up to a factor of 10 less scrubbed gas, less heater power, shows improved DMS resolution due to solvent modifier effects, and requires fewer and lower voltages in the interface. As a result (Table 3), it is the preferred design for further development.

DMS filtration is known to remove chemical noise that arises from low-level contaminants, fragments, instrumental contamination and solvents (for example, see Figure 17 in (Coy et al. 2011a), which shows the elimination of chemical noise after DMS selection for 2′-deoxycytidine). This is a significant advantage, because most atmospheric pressure ion sources have frequent interferents in the low mass range (Covey et al. 2009). This reduced noise floor is evident in the ESI-DMS figures through the zero signal level seen at high CoV values. As a result, DMS is much superior to a total current detector, because total ion current is approximately independent of chemical content when samples are dilute, and TIC noise, which is large due to the high detected ion current, will mask weaker features.

The development of integrated single-chip nano-flow LC systems opens up the possibility of smaller-scale instrumentation for a range of NASA mission and for clinical diagnostic applications. Operation at reduced pressure may also be possible, leading to improved declustering based on the Smith group results (Page et al. 2008). As a next step, we would like to test performance with a commercial nano-LC and with custom chip-LC units that have been provided to JPL by Agilent, Santa Clara, CA.

Table 1.

Power and weight requirements. A nano-ESI-DMS system operates at atmospheric pressure with a diaphragm micropump weighing 20 g providing flow of 300 ccm. Vacuum pumps and complex electronics increase the power and weight of MS systems. Resolutions listed for MS systems are approximate and do not include any chromatographic resolution. Sources (Griffin: http://gs.flir.com/griffin-400, Torion : http://www.torion.com/products/24, Cooks /Purdue: Sokol et al. (Sokol et al. 2008; Sokol et al. 2011)).

| Instrument | Commercial production | Weight | Power | Battery option | Resolution | Type | Sample intro |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Griffin 400/460 MS | Yes | 37–45 kg | 400–600 | yes | ~400 | trap MS, GC-MS | GC |

| Torion TRIDION 9 MS | Yes | 15 kg | 60–120 | yes | ~400 | trap MS, GC-MS | SPME, needle trap |

| Mini 10.5 MS (Cooks, Purdue) | No | 10 kg | 50 W | yes | ~300 | Ion trap | membrane, sorbent, D-API |

| ESI-DMS | No | 1 kg | < 10 W | yes | ~40 | DMS | nanospray to reaction chamber |

Acknowledgments

The work described in this paper was supported by Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Data acquisition on radiation biomarkers was supported by NIH U19 AI067773 and NIH R01 AI101798 (SLC, AJF).

Contributor Information

Stephen L. Coy, Email: steve.coy@post.harvard.edu.

Evgeny V. Krylov, Email: great418@gmail.com.

Erkinjon G. Nazarov, Email: enazarov@draper.com.

Albert J. Fornace, Jr., Email: af294@georgetown.edu.

Richard D. Kidd, Email: Richard.D.Kidd@jpl.nasa.gov.

References

- Belov ME, Clowers BH, Prior DC, Danielson WF, Liyu AV, Petritis BO, Smith RD. Dynamically multiplexed ion mobility time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2008;80(15):5873–5883. doi: 10.1021/ac8003665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennen RA, Yin H, Killeen KP. Microfluidic gradient formation for nanoflow chip LC. Anal Chem. 2007;79(24):9302–9309. doi: 10.1021/ac0712805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buryakov IA, Krylov EV, Makas AL, Nazarov EG, Pervukhin VV, Rasulev UK. DRIFT SPECTROMETER FOR THE CONTROL OF AMINE TRACES IN THE ATMOSPHERE. Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 1993;48 (1):114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum M, Staples G, Yin HF, Killeen K. Microfluidic LC-MS Chip Combined with Pngasef Enzyme Reactor and Make-Up Flow for Rapid Detection of Sialylated Glycans from Glycoproteins. Glycobiology. 2010;20 (11):1471–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Cooks R, Ouyang Z, Noll R, Manicke N, Costa A, Wu C, Xia Y, Dill A, Ifa D. Ambient Ionization and miniature mass spectrometry: Biomedical Applications. Biopolymers. 2009;92 (4):297–297. [Google Scholar]

- Covey TR, Thomson BA, Schneider BB. Atmospheric Pressure Ion Sources. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2009;28(6):870–897. doi: 10.1002/mas.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coy S, Cheema A, Tyburski J, Laiakis E, Collins S, Fornace A. Radiation metabolomics and its potential in biodosimetry. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2011a;87(8):802–823. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2011.556177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coy SL, Cheema AK, Tyburski JB, Laiakis EC, Collins SP, Fornace AJ. Radiation metabolomics and its potential in biodosimetry. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2011b;87(8):802–823. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2011.556177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coy SL, Krylov EV, Schneider BB, Covey TR, Brenner DJ, Tyburski JB, Patterson AD, Krausz KW, Fornace AJ, Nazarov EG. Detection of radiation-exposure biomarkers by differential mobility prefiltered mass spectrometry (DMS-MS) Int J Mass Spectrom. 2010;291(3):108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi P, Wu C, Matz LM, Clowers BH, Siems WF, Hill HH. Gas-Phase Chiral Separations by Ion Mobility Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2006;78(24):8200–8206. doi: 10.1021/ac0608772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiceman GA, Karpas Z. In: Ion mobility spectrometry. Eiceman GA, Karpas Z, editors. Vol. 350. Taylor & Francis/CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Li G, Cooks RG. Axial CID and high pressure resonance CID in miniature ion trap mass spectrometer using a discontinuous atmospheric pressure interface. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21 (2):209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Sugiarto A, Harper JD, Cooks RG, Ouyang Z. Design and characterisation of a multisource hand-held tandem mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2008;80 (19):7198–7205. doi: 10.1021/ac801275x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghitun M, Bonneil E, Pomies C, Marcantonio M, Yin HF, Killeen K, Thibault P. Miniaturization and Mass Spectrometry. Royal Soc Chemistry; Cambridge: 2008. Modular Microfluidics Devices Combining Multidimensional Separations: Applications to Targeted Proteomics Analyses of Complex Cellular Extracts. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm R, Yin H, Killeen K, Ninonuevo M, Lebrilla C, Ossola R, Aebersold R. High-resolution screening of various biomarker compounds by using a new HPLC-CHIP MS technology. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2005;4 (8):S81–S81. [Google Scholar]

- Hall A, Coy S, Kafle A, Glick J, Nazarov E, Vouros P. Extending the Dynamic Range of the Ion Trap by Differential Mobility Filtration. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. doi: 10.1007/s13361-013-0655-4. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AB, Coy SL, Nazarov EG, Vouros P. Development of rapid methodologies for the isolation and quantitation of drug metabolites by differential mobility spectrometry – mass spectrometry. International Journal for Ion Mobility Spectrometry. 2012;15(3):151–156. doi: 10.1007/s12127-012-0111-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafle A, Klaene J, Hall AB, Glick J, Coy SL, Vouros P. A differential mobility- mass spectrometry platform for the rapid detection and quantitation of DNA adduct dG-ABP. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6591. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanu A, Dwivedi P, Tam M, Matz L, Hill H. Ion mobility-mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2008a:1–22. doi: 10.1002/jms.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanu AB, Dwivedi P, Tam M, Matz L, Hill HH. Ion mobility-mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2008b;43(1):1–22. doi: 10.1002/jms.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov E. Comparison of the planar and coaxial field asymmetrical waveform ion mobility spectrometer (FAIMS) Int J Mass Spectrom. 2003;225:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Krylov E. Differential mobility spectrometer: optimization of the analytical characteristics. International Journal for Ion Mobility Spectrometry. 2012;15(3):85–90. doi: 10.1007/s12127-012-0099-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov E, Coy S, Vandermey J, Schneider B, Covey T, Nazarov E. Selection and generation of waveforms for differential mobility spectrometry. Review of Scientific Instruments. 2010;81(2) doi: 10.1063/1.3284507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov EV, Coy SL, Nazarov EG. Temperature effects in differential mobility spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2009;279(2–3):119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2008.10.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov EV, Nazarov EG. Electric field dependence of the ion mobility. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2009;285(3):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2009.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapthorn C, Pullen F, Chowdhry BZ. Ion mobility spectrometry-mass spectrometry (IMS-MS) of small molecules: Separating and assigning structures to ions. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2013;32(1):43–71. doi: 10.1002/mas.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DS, Vouros P, Miller RA, Nazarov EG. Using a nanoelectrospray-differential mobility spectrometer-mass spectrometer system for the analysis of oligosaccharides with solvent selected control over ESI aggregate ion formation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2007;18(3):502–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DS, Vouros P, Miller RA, Nazarov EG, Morris JC. Characterization of gas-phase molecular interactions on differential mobility ion behavior utilizing an electrospray ionization-differential mobility-mass spectrometer system. Anal Chem. 2006;78(1):96–106. doi: 10.1021/ac051217k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limero T, Reese E, Wallace W, Cheng P, Trowbridge J. Results from the air quality monitor (gas chromatograph-differential mobility spectrometer) experiment on board the international space station. International Journal for Ion Mobility Spectrometry. 2012;15(3):189–198. doi: 10.1007/s12127-012-0107-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason EA, McDaniel EW. Transport Properties of Ions in Gases. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- NASA Astrobiology: Life in the Universe. [accessed 13 Dec 2012.,];National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NASA Astrobiology: Life in the Universe. 2012 https://astrobiology.nasa.gov/, https://astrobiology.nasa.gov/roadmap/

- Nazarov E, Miller R, Coy S, Krylov E, Kryuchkov S. Software simulation of ion motion in DC and AC electric fields including fluid-flow effect (SIONEX microDMx software) Int J Ion Mobility Spectrom. 2006a;9 [Google Scholar]

- Nazarov EG, Coy SL, Krylov EV, Miller RA, Eiceman GA. Pressure effects in differential mobility spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2006b;78(22):7697–7706. doi: 10.1021/ac061092z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Z, Cooks RG. Miniature Mass Spectrometers. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry. 2009;2(1):187–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-060908-155229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page JS, Tang K, Kelly RT, Smith RD. Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray Source and Interface for Improved Sensitivity in Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2008;80(5):1800–1805. doi: 10.1021/ac702354b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle SD, Giles K, Wildgoose JL, Williams JP, Slade SE, Thalassinos K, Bateman RH, Bowers MT, Scrivens JH. An investigation of the mobility separation of some peptide and protein ions using a new hybrid quadrupole/travelling wave IMS/oa-ToF instrument. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2007;261(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2006.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rorrer LC, Yost RA. Solvent vapor effects on planar high-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2011;300(2–3):173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2010.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B, Covey T, Coy S, Krylov E, Nazarov E. Planar differential mobility spectrometer as a pre-filter for atmospheric pressure ionization mass spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2010a;298(1–3):45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B, Nazarov E, Covey T. Peak capacity in differential mobility spectrometry: effects of transport gas and gas modifiers. International Journal for Ion Mobility Spectrometry. 2012;15(3):141–150. doi: 10.1007/s12127-012-0098-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BB, Covey TR. High Performance DMS/MS Interface with Chemically Modified Separations. 2012 http://wwwabsciexcom/Documents/Events/pittcon-Schneider-PittCon-2012pdf.

- Schneider BB, Covey TR, Coy SL, Krylov EV, Nazarov EG. Chemical Effects in the Separation Process of a Differential Mobility/Mass Spectrometer System. Anal Chem. 2010b;82(5):1867–1880. doi: 10.1021/ac902571u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BB, Covey TR, Coy SL, Krylov EV, Nazarov EG. Control of chemical effects in the separation process of a differential mobility mass spectrometer system. Eur J Mass Spectrom. 2010c;16(1):57–71. doi: 10.1255/ejms.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shvartsburg A, Li F, Tang K, Smith R. High-resolution field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry using new planar geometry analyzers. Anal Chem. 2006;78(11):3706–3714. doi: 10.1021/ac052020v|10.1021/ac052020v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shvartsburg AA. Differential Ion Mobility Spectrometry: Nonlinear Ion Transport and Fundamentals of FAIMS. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; Boca Raton, FL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sokol E, Edwards K, Qian K, Cooks R. Rapid hydrocarbon analysis using a miniature rectilinear ion trap mass spectrometer. Analyst. 2008;133(8):1064–1071. doi: 10.1039/b805813j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol E, Noll RJ, Cooks RG, Beegle LW, Kim HI, Kanik I. Miniature mass spectrometer equipped with electrospray and desorption electrospray ionization for direct analysis of organics from solids and solutions. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2011;306(2–3):187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2010.10.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tadjimukhamedov FK, Jackson AU, Nazarov EG, Ouyang Z, Cooks RG. Evaluation of a differential mobility spectrometer/miniature mass spectrometer. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21(9):1477–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CW, Yost RA, Garrett TJ. High-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry with solvent vapor addition: a potential greener bioanalytical technique. Bioanalysis. 2012;4(11):1363–1375. doi: 10.4155/bio.12.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyburski JB, Patterson AD, Krausz KW, Slavik J, Fornace AJ, Jr, Gonzalez FJ, Idle JR. Radiation metabolomics. 1. Identification of minimally invasive urine biomarkers for gamma-radiation exposure in mice. Radiat Res. 2008;170(1):1–14. doi: 10.1667/RR1265.1. RR1265 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Manicke NE, Cooks GR, Ouyang Z. Miniaturization of Mass Spectrometry Analysis Systems. JALA. 2010;15(6):433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jala.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]