Abstract

Stress and trauma can compromise physical and mental health. Rural Alaska Native communities have voiced concern about stressful and traumatic events and their effects on health. The goal of the Yup’ik Experiences of Stress and Coping Project is to develop an in-depth understanding of experiences of stress and ways of coping in Yup’ik communities. The long-range goal is to use project findings to develop and implement a community-informed and culturally grounded intervention to reduce stress and promote physical and mental health in rural Alaska Native communities. This paper introduces a long-standing partnership between the Yukon-Kuskokwim Regional Health Corporation, rural communities it serves, and the Center for Alaska Native Health Research at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Within the context of the Stress and Coping project, we then discuss the value and challenges of taking a CBPR approach to advance science and address a priority community concern, and share strategies to respond to challenges. Focus groups were conducted to culturally adapt an existing structured interview and daily diary protocol to better fit Yup’ik ways of knowing. As modified, these interviews increased understanding of stress and coping particular to two Yup’ik communities. Challenges included the geographical nature of Yup’ik communities, communication barriers, competing priorities, and confidentiality issues. Community participation was central in the development of the study protocol, helped ensure that the research was culturally appropriate and relevant to the community, and facilitated access to participant knowledge and rich data to inform intervention development.

Keywords: stress, coping, Alaska Native, rural, CBPR

The negative effects of chronic stressors on physical, mental, and behavioral health are well established (Juster, McEwen, & Lupien, 2009; McEwen, 1998). American Indian and Alaska Native communities shoulder a disproportionately high burden of stress and trauma. This has been attributed, in part, to historical trauma, such as a vast history of colonization, loss of culture and epidemics, and to rapid changes in culture and lifestyle patterns (Dinges & Joos, 1988; Duran & Duran, 1995; Walters & Simoni, 2002; Wolsko, Lardon, Hopkins, & Ruppert, 2006). Such changes include the partial reliance on a cash economy, adaptations in traditional subsistence activities and migration, as well as a relatively new dependence on snowmachines, cell phones, and processed store bought foods (Bersamin et al., 2008; Lardon, Drew, Kernak, Lupie, & Soule, 2007). Trauma and stress experienced by Indians and Natives has been inextricably linked with unacceptably high rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and suicide (Manson, 1996; Manson, Beals, Klein, & Croy, 2005; Robin, Chester, & Goldman, 1996). These mental and behavioral health disparities pose detrimental effects to the health of individuals, families, and entire communities (Hawkins, Cummins, & Marlatt, 2004; Manson, Bechtold, Novins, & Beals, 1997). For example, intentional injury, specifically suicide, is one of the leading causes of death for Alaska Natives (Lanier, Kelly, Maxwell, McEvoy, & Homan, 2006), and a particularly critical issue among young Alaska Native men (Alaska Injury Prevention Center, Critical Illness and Trauma Foundation Inc., & American Society for Suicidology, 2007; Goldsmith et al., 2004). In turn, suicide has been associated with depression, severe stress, substance use, conflict, isolation from family and community, maladaptive coping, historical trauma, and loss of culture (LaFromboise, Medoff, Lee, & Harris, 2007; Manson et al., 1997; Wexler, 2006; Wilson et al., 1995). Suicide affects not only individuals and families, but the health and well-being of an entire community (Wexler, 2006). Alcohol abuse also devastates community health as a primary factor in suicide, and through its association with homicide, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, domestic violence, and sexual assault (Goldsmith et al., 2004). However, individual, family and community strengths are protective against alcohol abuse among Alaska Natives, and facilitate reflection and decisions to maintain sobriety (Mohatt, Rasmus, et al., 2004).

Rural Alaska Native communities have voiced great concern about stressful and traumatic events and their impact on health (Wolsko et al., 2006). Research conducted by University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Center for Alaska Native Health Research (CANHR) in partnership with Yup’ik communities in Southwest Alaska highlights the importance of enculturation (e.g., immersion in traditional Yup’ik values and practices and cultural identity) as a buffer to certain experiences of stress (Wolsko et al., 2006; Wolsko, Lardon, Mohatt, & Orr, 2007). Specifically, enculturation is associated with greater happiness and spiritual coping, and less drug and alcohol coping in the face of cultural change (Wolsko et al., 2007).

Findings from preliminary research in tandem with the identification of stress and its impact on health as a priority concern of partner Yup’ik communities gave rise to the Yup’ik Experiences of Stress and Coping Project [Stress and Coping Project]. The goal of this project is to develop an in-depth understanding of experiences of stress and ways of coping in Yup’ik communities. The long-range goal is to use project findings to develop and implement a community-informed and culturally grounded stress management intervention for Yup’ik communities.

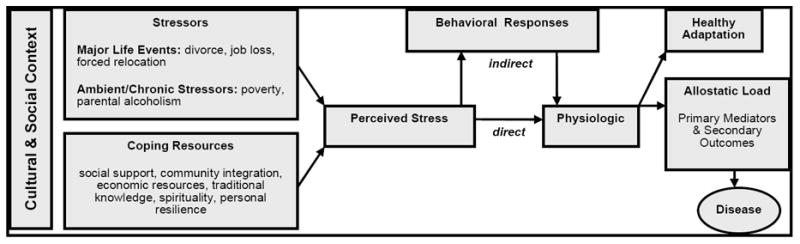

The Stress and Coping Project is guided by a framework that conceptually illustrates the direct and indirect pathways through which psychosocial stress can impact health. The framework integrates McEwen’s model of stress physiology (Juster et al., 2009; Mcewen, 1998; McEwen & Seeman, 1999; McEwen & Stellar, 1993), ecological models of stress and coping (Dohrenwend, 1978; Hobfoll, 1988; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), and frameworks for understanding stress and coping among American Indians and Alaska Natives (Dinges & Joos, 1988; Walters, Simoni, & Evans-Campbell, 2002). As shown in Figure 1, individual, family, and community stressors (e.g., job loss, family suicide, acculturation pressures) and coping resources (e.g., social support, spiritual guidance, community integration) interact to influence perceptions of stress. These perceptions influence physical and mental health directly by affecting psychological and physiological states (e.g., depression, blood pressure, stress hormones) and indirectly by affecting health behaviors (e.g., smoking, alcohol use) (Juster et al., 2009; Pickering, 1999; Taylor, Repetti, & Seeman, 1997; Tice, Bratslavsky, & Baumeister, 2001). Critical to the framework are the social and cultural context and their effects on the experience of stressors, the availability and use of coping resources, and the pathways through which stress and coping impact health. Yup’ik community leaders and other stakeholders were most interested in information that would be useful for development of a stress management program. In response, the Stress and Coping Project focuses on aspects of the model with the greatest practical utility for planning a stress management program.

Figure 1.

Pathways from Stress to Disease

Call for CBPR Research with Alaska Native Communities

Research plays a necessary role in informing appropriate strategies for identifying and addressing priority individual and community needs (Noe et al., 2007; Trickett & Birman, 1989; Trickett & Espino, 2004; Trimble, 2009a, 2009b). The dearth of research with ethnic minority populations in North America, particularly Alaska Native, precludes the ability to develop beneficial evidence-based practices. Significant concerns expressed by American Indian and Alaska Native populations about research conducted on, in, and with their own communities can perpetuate mistrust and pose barriers to participation (American Indian Law Center, 1999; Burhansstipanov, Christopher, & Schumacher, 2005; Cochran et al., 2008; Trimble, 2009a, 2009b). In part, this mistrust is historically rooted within a tradition of research that employs methods and practices that fail to honor and incorporate local cultural traditions, Native language, and the importance of identity and self-determination (Burhansstipanov et al., 2005). Particularly damaging are repercussions from a history of unfulfilled promises made by researchers at the outset of a study that guarantee significant benefit to the participating individuals and communities in terms of new knowledge, data, and services. When these promises are broken, Native communities can actually be harmed, particularly when findings are reported in ways that reinforce negative stereotypes, fail to identify community strengths while emphasizing negative behaviors, and perpetuate the misconception that indigenous people, as a whole, represent a problem that needs to be solved by outsiders (Casillas, 2006; Cochran et al., 2008). Such misperceptions can result when projects exclude indigenous participants from the research decision-making process (Burhansstipanov et al., 2005) and fail to incorporate indigenous ways of knowing (Chino & DeBruyn, 2006).

In response to these and other concerns, research principles have been set forth to guide ethical research conducted with American Indian and Native Alaska populations. These guiding principles expand on normative professional research ethical standards to accentuate the importance of establishing firm collaborative relationships with participating communities (C. B. Fisher et al., 2002; Jason, Keys, Suarez-Balcazar, Taylor, & Davis, 2004; Mohatt, Thomas, & Team, 2005; Trickett & Espino, 2004). Noteworthy are the eight parallel principles developed by the National Science Foundation’s Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee (IARPC) and the Alaska Federation of Natives which emphasize the importance of: 1) informing community leaders of planned research activities; 2) involving community members throughout the research process; 3) affording respect to cultural traditions, languages, and values; 4) providing a clear and transparent informed consent process; 5) protecting sacred lands and intellectual property; 6) guaranteeing confidentiality and anonymity; 7) providing all research materials to the community; and 8) communicating results in a manner that is appropriate and responsive to local concerns (National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs [OPP], 2006).

These guiding principles are also reflected in elements defining a community based participatory research (CBPR) approach. CBPR is a collaborative approach to research that focuses on establishing the participation and influence of “community” in the process of creating knowledge (Mohatt et al., 2005; Trickett & Birman, 1989; Trickett & Espino, 2004). An important distinction of this approach is conducting research with a community as a social and cultural entity with active engagement and influence of community members in all aspects of the research process (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). The principles of CBPR are congruent with those created for research with American Indian and Alaska Native populations. As such, CBPR (Cochran et al., 2008; P. A. Fisher & Ball, 2005; Noe et al., 2007) is well suited for use with Alaska Native communities because it facilitates inclusion of community values, cultural heritage, and historical perspectives (P. A. Fisher & Ball, 2005).

Indigenous communities strongly value personal relationships and face-to-face communication. Consequently a CBPR approach to research is vital to better understanding and addressing the complex health disparities experienced by Alaska Native populations. However, this perspective and orientation also adds new challenges to conducting research with ethnocultural populations (Trimble, 2009a, 2009b; Trimble & Fisher, 2005; Trimble, Scharron-del Rio, & Bernal, 2010). The purpose of this paper is to describe how the Center for Alaska Native Health Research (CANHR) conducts CBPR in rural Alaska Native communities, the value of CBPR for advancing science and addressing community needs, and the challenges and facilitators to conducting a CBPR process within the context of identifying stressors and coping strategies in Yup’ik communities.

Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation and CANHR Partnership

The Stress and Coping Project is one of several projects conducted within a long-standing partnership developed between the Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation (YKHC), the tribal communities the corporation represents, and the Center for Alaska Native Health Research (CANHR). The YKHC is a tribal owned, non-profit organization that manages a comprehensive health care system on behalf of 58 federally recognized Tribes in 50 rural communities located in southwest Alaska. With a mission of “Working together to achieve excellent health,” the YKHC is governed by a Board of Directors that comprises leaders from the tribal communities it serves (Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation). Important contributions of YKHC include the human subjects’ protection committee that helps to provide oversight over CANHR projects, and their membership on the CANHR external advisory council.

The 50 communities represented within the YKHC service area are each self-governed by a Tribal Council whose officials are elected by community tribal members. Each Tribal Council decides with which research projects they collaborate. Two Tribal Councils identifying stress as a priority community issue are the partners on the Stress and Coping Project. To ensure optimum support, the Tribal Council also formed a community steering committee (CSC) composed of elected officials and other community members. The CSCs work closely with the academic team in providing feedback and developing a culturally appropriate research process.

CANHR, a Center for Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Research Resources, is located within the University of Alaska Fairbanks Institute of Arctic Biology, and was established to develop unique biomedical knowledge for translation into culturally appropriate research and intervention for the prevention and reduction of health disparities among Alaska Natives. CANHR has established long-term and trusting relationships with Yup’ik communities and provides an effective model for culturally appropriate and long-term research (Boyer et al., 2005). Adhering to the principles of CBPR, CANHR works in partnership with regional health corporations and the communities they serve in conceptualizing, developing, and implementing research and interventions that are appropriate and relevant (CANHR, 2009). The Stress and Coping Project adopted CANHR’s methods of community engagement, and builds on its formation of trust and collaboration with the YKHC and two of its associated tribal communities. CANHR-based researchers and external mentors represent the academic partner of the Stress and Coping Project. Included are faculty, staff, and students from both the University of Alaska Fairbanks and Anchorage who contribute diverse research, substantive, and experience-based expertise within fields of psychology, public health, nursing, and Yup’ik culture.

Method

The stress and coping project grant application was developed to address a priority concern identified by the community, with critical input, guidance, and ultimately, approval from the YKHC prior to submission for funding. With intent to use findings to apply for additional funding to develop and implement a culturally grounded stress management program for Yup’ik communities, the overarching goal of the Stress and Coping project is to develop an in-depth understanding of the stressors experienced specifically by Yup’ik individuals and families from two partnering communities and the strategies they use to cope with stress. To achieve this goal the Stress and Coping project undertook a two phase research protocol. Phase One involved developing culturally appropriate data collection materials and protocols to gain in-depth understanding. Phase Two involves implementing data collection activities using the materials and protocol developed during Phase One, along with data analysis, interpretation, and dissemination.

Phase 1: Project Materials and Protocol Development

To gain insight about the particular stressors experienced by Yup’ik communities, three data collection protocols were developed, including those for a Community Stress and Coping Interview, a Lifetime Events and Trauma Interview, and a Digital Audio Diary.

The Community Stress and Coping Interview is a short interview guide that focuses specifically on individuals’ perceptions of stress and coping experienced at the community level. In addition it invites participants to share suggestions for developing a successful community-based stress management program.

The Lifetime Events and Trauma Interview guide invites participants to share information about their personal experiences with an array of different types of stressors and how they were able to cope. As a foundation, the interview drew upon questions from an existing Lifetime Events and Trauma survey used in the continental US to assess stress and trauma in American Indian communities (American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project – AI SUPERPFP; Manson et al., 2005).

Lifetime Events interview participants are also invited to complete Audio Diaries. For these diaries, participants are provided digital audio recorders, and are asked to take a few minutes each day (for one week) to record their thoughts and feelings about the stressors they experienced or were reminded of during that day. Specifically, participants are asked to talk about how their stress affected them and describe their coping strategies for the stressors experienced. In addition, participants are also invited to talk about the positive aspects of their day. This type of interval-contingent Experience Sampling method (Wheeler & Reis, 1991), assessing experiences at daily intervals, can be an important adjunct to understanding stress and coping. Retrospective recollections of stress and coping are prone to recall errors which can be minimized by assessing responses to stressful experiences closer to the time frame when stress occurs ((Ptacek, Smith, Espe, & Raffety, 1994; Stone et al., 1998). Furthermore, audio recording is consistent with the oral tradition in Yup’ik culture. Research also suggests that narrative processing of stressful experiences by writing or talking about them results in better health and psychological well-being (Frattaroli, 2006; Pennebaker, 1993; Ullrich & Lutgendorf, 2002). Thus, recording thoughts and feelings could provide benefit to participants.

Community participation in protocol development

To ensure that the interview guides accurately reflected experiences unique to Yup’ik culture, we gained insightful feedback about the interview questions and protocol from the community tribal councils and community members during three extended visits to the participating communities. During these visits, we met with both tribal councils and the community steering committee, and conducted a series of 11 focus groups. The community steering committee provided feedback on focus group procedures (including the content and structure of PowerPoint slides), interview questions, and study protocol. Individuals from the committee helped pilot test the audio diary protocol to provide their feedback on how it worked for them. The committee also helped recruit participants for the focus groups. In addition, two men from the community steering committee helped co-facilitate men’s focus groups, and an elder from the steering committee served as a translator both for the steering committee meeting and for some of the focus groups.

The focus groups averaged 9 participants and lasted approximately two hours. During the focus groups, PowerPoint slides that listed each interview question were presented for discussion. Participants were asked to assess the fit of each question with the Yup’ik life experience, and to provide suggestions for rewording, omitting, and developing new questions. To protect confidentiality while discussing the questions, participants were asked to refrain from actually answering the questions in terms of their own or other’s experiences with stress. However, many participants still answered in terms of their experiences and told stories in response to the questions, consistent with the oral tradition in Yup’ik culture. The research team’s emphasis on confidentiality, and the commitment of focus group participants to keep what was shared in the group confidential, helped participants feel comfortable sharing their experiences even when not directly prompted to share. Both the responses providing direct feedback on the interview, and the stories participants shared, were useful in guiding and validating the interview.

To accommodate both English and Yup’ik language speakers, most focus groups were co-facilitated by a Native Yup’ik speaker and a CANHR researcher. Further, to foster open sharing, and diverse representation across age and gender groups, we conducted focus groups specifically for younger men, younger women, older men, and older women, based on previous experiences of working with these communities. This was especially important for younger Yup’ik participants who out of respect will often defer to community elders and men (Wolsko et al., 2006). Conducting separate men’s and women’s focus groups is consistent with traditional Yup’ik cultural practices. In the past, boys were instructed by men in the Qasgiq – “the men’s house”, while the mother or female relative instructed the girls. However, we also conducted three mixed (age and gender) focus groups to accommodate strong community values for inclusion and desires to hear others’ views as well as share their own in a group that included diverse segments of the community.

The community feedback was integrated into a new version of the Lifetime Events and Trauma Interview. Examples of topics for which new questions were added include those pertaining to: individual understanding of stress, feeling accepted in the community, social support, loved ones in the military being deployed overseas, conflicts between the “Kass’aq” (non-Native) and Yup’ik, and youth and elder ways of living, parenting issues, gossip, bullying, access to healthcare, isolation, geographical barriers, climate change, migration, expense of food and fuel, lack of law enforcement, community involvement, and adult educational programs. Feedback from the community also emphasized individual and community differences in stressors and effective coping strategies, and the importance of the stress management program being sensitive to those differences.

A separate and shorter Community Stress and Coping Interview was also developed. Rationale for developing this instrument was based on the community value of inclusiveness, and the need for a screening tool that could help identify participants who might be vulnerable (experiencing acute crisis or other mental health issues) or at risk for adverse reactions if they were to answer the extremely sensitive and personal questions included in the Lifetime Events and Trauma Interview. The shorter community perspective interview could be completed with many individuals who wished to share their perspectives, and then researchers could decide, case-by-case, who would be invited to complete the longer Lifetime Events and Trauma Interview. Not only would this minimize risk of harm, but it would also ensure the correct number of participants were included per the purposive sampling plan (see sampling).

With regard to the Audio Diaries, focus group participants were generally enthusiastic, and even interested in pilot testing the protocol. They recorded their thoughts and feelings about stress they experienced and let us know what it was like to use the audio diaries. Nevertheless, it became clear that several community members, particularly elders, were uncomfortable with using a digital recorder. This was attributed to the technology itself, and to the concern that other individuals might find and listen to the recording. In response, it was decided that the Audio Diary protocol would be an optional component of the study. We also offered that the diaries could be completed in writing, via in-person reporting, or over the phone with a research team member.

Member checking

To ensure that newly revised interview accurately reflected community feedback, another round of focus groups was conducted after the first series of revisions. The focus groups resulted in additional suggestions for improvement along with new opportunities for researchers and community members to interact and discuss important issues related to stress and coping. Final revisions to the data collection materials and protocol were submitted for approval by both the YKHC and the University of Alaska Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects (IRB). The traditional council in the community also provided feedback on and approved changes in the assessment, sampling, recruitment, and other study procedures, including the ones described above.

Phase 2: Implementation of Interviews

Sampling

Our goal was to complete the shorter Community Stress and Coping Interview with up to 60 participants in each of the two partnering communities, and the longer Lifetime Events and Trauma Interview with up to 30 participants in each of the two communities (who would also be invited to complete Daily Diaries). Data collection was to be completed in two waves, where researchers would visit each of the two communities two times at different times of the year to gain perspectives on Stress and Coping that might be seasonally based. A major consideration was to develop a sampling strategy that would ensure a diverse representation of perspectives while respecting the community desire for inclusiveness. The project employed a purposive stratified sampling strategy that would be feasible, useful and respectful in small rural communities while allowing a diverse representation of perspectives by age and sex. Random sampling would not be accepted in these communities. However, the community supports the value of including diverse perspectives from multiple segments of the community.

With guidance from the tribal council, we created a matrix to guide our sampling plan that involved recruiting participants by gender and age range, until we completed the 30 shorter community interview with the goal of including five women and five men within each of the designated age ranges: younger (18-30 years), middle (31-50 years), and older (51 years and older) age ranges. Of these participants a subset of two to three women and two to three men within each age range (for a total of 15) would be invited to complete the Lifetime Events and Trauma interview and Audio Diaries.

Interviews

The second phase of the project involved actually conducting data collection activities using the revised interview and Audio Diary protocols developed during Phase One. Prior to conducting interviews, we met with the community tribal council to provide an update on the project, and review the data collection protocol, including the sampling and recruitment plan. With support and championing from the tribal council, we successfully recruited men and women from varying age groups and from different areas of the community.

The tribal council was invaluable to our ability to recruit participants. Specifically, the tribal council administrator, an individual who is well known and respected in the community, was particularly instrumental in recruitment. He projected great respect for the partnership, project and its goals, and used his personal and professional connections to ensure that community members were aware of the project, its purpose and the interview opportunities. Whenever participants from a certain sex or age group were needed, he was able to recruit individuals throughout the community to achieve our sampling goals. In this community of approximately 700 persons, those who participated were known by each other but they did not represent any clique.

The short community interviews helped inform purposive stratified sampling, and identify individuals who might have been too vulnerable to participate in the more intense Lifetime Events and Trauma Interview. Based on discussions with the tribal council and the experiences participants shared during focus groups and interviews, it was clear that individuals and the community as a whole had historically encountered extremely traumatic situations and were also currently experiencing a great deal of stress. To try to minimize the risk of causing additional stress during the interviews, we provided referrals to available services, “checked in” with participants during and after the interview, offered breaks as needed, and reminded participants that they were free to skip questions or stop the interview at any time. The research team also consulted with the local behavioral health provider and supervising clinician about the research protocol to minimize risks, and referred participants to them.

Results

Community participation was vital in the Stress and Coping project. However, the Stress and Coping Project partnership encountered challenges and facilitators that are both common to the CBPR process, and unique to Alaska and the sociocultural context of Yup’ik communities, that are underserved, marked by low-income with high costs of living, and are rural and extremely remote. Essentially, the day-to-day operations of the project experienced challenges related to: 1) Geographical nature of Yup’ik communities; 2) Communication challenges; 3) Competing priorities; and 4) Confidentiality issues, each of which will be explicated in turn:

Geographical Nature of Yup’ik Communities

Geography and weather conditions made travel to and from partnering communities extremely difficult. Due to the lack of a road system, at least one full travel day was required and involved a commercial flight to the regional hub, followed by small-craft “bush” plane to the community’s airstrip, then snowmachine or 4-wheeler from the airstrip to the school or community center. Once in the community, people typically walk and use snowmachines, 4-wheelers, and boats. Recent increases in fuel costs have made travel for research far more expensive than what was allotted in the original grant’s budget. Unpredictable and extreme weather conditions led to travel delays, postponed project-related activities, and often extended stays in the community. Flexible schedules for all partners and adequate travel funds were paramount.

Communication Challenges

Face-to-face interaction is the preferred method of communication in the communities. Yet, in-person meetings were not as frequent as would be ideal. This was, in part, attributed to the remoteness of Yup’ik communities. Supplementing in-person interactions with long-distance communication was vital to the Stress and Coping Project’s CBPR process. Nevertheless, there have been challenges to such communication. For example, calls between communities within Alaska were long-distance. Although CANHR offered a toll-free number, it was not specific to the project and was used infrequently. Furthermore, many people in the community used VHF radios to communicate within their community and some did not have a telephone in their home. Cell phone service has recently been introduced, but they can be cost prohibitive and result in disconnected numbers. Regular communication with community partners has also been challenged by limited internet access capacity, as internet is only available in certain homes and public buildings (e.g., the school) and is often disrupted due to weather. Finally, language differences have proven difficult. Specifically, because many elders’ and community partners’ first language was Yup’ik, communication required an interpreter. Furthermore, some words or concepts do not have a direct equivalent in English, so interpreters often used several examples to get the point across. Likewise, some Yup’ik words do not have a direct translation in English. It is difficult to “find the right word” when there is no “right word”.

Competing Priorities

Competing priorities often presented challenges for community and academic partners. An important community priority is the need for a timely intervention that addresses the stress in the community. However, it is important to first understand stress and coping in the community, in order to inform the intervention and provide preliminary data to be used in grant applications for funding development and testing of the intervention. The time it takes for the research trajectory, from development of culturally appropriate measures, to assessment for understanding causes of stress and coping strategies and resources, to results interpretation and dissemination, to use of results in grant applications to develop the program, created a tension with community needs for a timely intervention addressing the issues currently affecting the community. Ongoing conversations and education among all partners about research and community life were necessary to increase awareness of the need to better understand stress and coping before an appropriate intervention could be developed.

Competing priorities in the lives of community and academic partners also presented challenges. Daily life in rural Yup’ik communities extensively revolves around subsistence activities, including hunting, fishing, gathering, processing, and sharing food. These activities have been a way of life for many years. However, with limited opportunities for full time employment, subsistence activities continue to have cultural, social and economic importance. In response, all project-related activities were scheduled around subsistence schedules such as those taking place during summer and early fall, when many families left for fish camp and hunting. For example, a data collection trip was rescheduled when a five-year moratorium on moose hunting was lifted and many men in the community left to hunt moose to feed their families. Scheduling was a challenge, because most research-related travel and activities needed to occur during the winter or early spring, when travel is increasingly arduous. At the same time, CANHR researchers also needed to juggle their professional and personal schedules, responsibilities, and priorities. Also important was that all travel activities be respectful and sensitive to events such as holidays or celebrations, or times when the community was coping with a crisis such as a flood, or a death in the community.

Confidentiality Issues

Yup’ik communities are essentially rural and small, with populations ranging from less than 100 to 1000 residents. As such, everyone is interconnected and knows the happenings in the community. This posed both strengths and challenges. On one hand, it facilitated community awareness of the project and recruitment through word of mouth. However, it also posed challenges to maintaining confidentiality. Community members were aware of research activities taking place in their community. They saw participants arriving for data collection activities and therefore knew who was taking part in the research. People often lived with many others in the same home, and when a researcher made calls to schedule or remind a participant of an appointment, some knew that person was a participant in the study. As a result, maintaining confidentiality of research participants’ identities was a challenge in the community.

IRB principles emphasize both the confidentiality of participants’ identities as well as their responses. However, we have learned that participants’ main confidentiality concern is the confidentiality of specific responses to the sensitive interview questions about stress and coping, not the confidentiality of their status as a research participant. In response, we used interviewers who did not live in the community. This decision was supported by community partners who preferred that interviews be conducted by academic partners. This may contrast with ideas that local interviewers should be involved in data collection (P. A. Fisher & Ball, 2005). However, this decision was important to addressing community preferences and needs, reducing participants’ concerns about others in the community learning about their responses, and allowing participants to open up and share sensitive personal experiences. Although involvement of community partners in the research is important, we cannot make the assumption that the community desires extensive involvement in all tasks. Community partners helped guide research activities and recruit participants. However, they did not conduct individual interviews, due to these confidentiality concerns.

Discussion

A key question raised with regard to CBPR is, does it add value to the science of research and, if so, how. There are a number of key areas which it is clear what the value added nature of CBPR was for our project.

Gaining access to participant knowledge. Stress is difficult to discuss and demands that a rapport has been established between the research team and the participants. Community members showed a willingness to share sensitive personal information with the outside interviewers, trusting the confidentiality of the information shared. We believe this trusting relationship was based on previous positive experiences with CANHR researchers. These experiences included time spent with researchers during visits to the community, the willingness of the research team to respond to community concerns, and the commitment to a long-term partnership. In addition, the community and tribal council support for the project facilitated participants’ commitment to share personal information that could provide vital insight when developing a relevant and targeted stress management program.

-

Richness of data. Qualitative data aims to gather rich, fully described ideas about a phenomenon. Without this richness the data collection can yield trivial sets of data that are characterized by a paucity of detail. Although we are just beginning to examine the results of the interviews, we are finding that our partnering communities have shared experiences of significant trauma as well as considerable day to day stress, including the stress of cultural and economic change. Trauma and stress affects not only the individual and family, but the entire community. For example, a participant noted, “It’s kind of a close-knit community, like most of them are related and like when there is a suicide or someone’s, like a traumatic injury, it affects not just one person, but a lot of people in the community.” Participants’ stories about stress and coping also highlighted internal and external forces acting on their community, as well as the traditions and values that help the community heal. For example, a participant said “When we continue to use what our elders have told us, things start to emerge that would be helpful for us”.

A key factor in participants’ sharing their perspectives was that the questions resonated with their experiences. Many of the stressors participants reported were assessed with questions that were added in response to community steering committee and focus group feedback. Thus, community participation was critical for developing an interview tool that assessed the types of stressful experiences commonly experienced in these communities. Further data collection, analysis and community participation in interpretation of results will facilitate an understanding of the stressful experiences affecting these communities, how people find healthy ways of coping with stress, and how traditional values and practices, as well as contemporary practices for dealing with change, can be integrated into stress management programs.

Reducing attrition. Tracking participants after they had taken part in the Community Stress and Coping Interview to schedule them for the longer interview proved difficult. Some did not have phones, others had cell phones that were no longer in service, and many had competing priorities that took precedence over completing the interviews. In response, the team scheduled appointments for Lifetime Events and Trauma Interview immediately after the Community Stress and Coping Interview, and worked with the tribal council and local research assistants to facilitate recruitment and tracking. Local community members, who are familiar with the community, culture, and language, play a crucial role in all phases of the project (e.g., providing feedback on the study protocols, recruiting participants, contextualizing results, helping to plan the intervention, and problem solving implementation issues as they arise). Nevertheless, they do not conduct interviews and will see only compiled data which does not identify particular participants’ responses. As noted in the results, the communities chose to have outside interviewers to assure confidentiality and trust, opening a space for participants to share sensitive information with interviewers who do not see them in the community on a daily basis. The role of local staff will increase as the project moves to results dissemination and intervention planning and implementation stages. The current project includes part-time community research positions, but a subsequent grant will include more positions for community members who will be involved in planning, coordinating, and implementing the intervention.

Lessons Learned

Community guidance and participation was critical throughout the phases of the stress and coping project. The community determined priorities for research, guided the research questions, provided valuable input for developing the interview and diary protocol, guided sampling and recruitment procedures, and planned the timing of subsequent data collection visits. Community participation will continue to be critical for guiding data analysis and interpretation, and planning the intervention. The isolation of these rural communities, combined with researchers’ academic responsibilities, pose challenges to CBPR, yet opportunities for face-to-face interaction and community guidance are critical.

Project experiences illustrate strategies for addressing CBPR principles in health disparities research in rural Alaska Native communities, even with geographical and communication barriers. The tribal councils and the research team developed a respectful relationship, and met together to guide the project and nurture the partnership when the researchers were in the community. Researchers were also welcomed at community activities, were present and approachable to community members out in the community, and forged relationships with local teachers and community members employed at the school and community center. This allowed the researchers to acquire a deeper understanding of the community’s strengths and barriers, and also allowed the community members to learn more about the researchers, facilitating relationship-building. Developing and maintaining long-term, trusting relationships in community research and intervention is a critical part of the ‘real’ work itself” (Israel et al., 1998, p. 62).

Our experiences also illustrate the need to balance methodological rigor with flexibility and responsiveness. This issue is faced in many CBPR projects (Mohatt, Hazel, et al., 2004; Stiffman, Freedenthal, Brown, Ostmann, & Hibbeler, 2005). It requires responsive adjustments in the methodology to address community needs, priorities, and cultural issues. For example, random sampling to recruit interview participants would not be feasible nor accepted in the communities, violating community values of inclusion. Purposive sampling combined with multiple opportunities for participation helped address the need for inclusion and the need for diverse community perspectives on stress and coping. Gathering focus group feedback only through direct input on the questions would miss the less direct but very valuable input in stories participants chose to share about life in the community and the stressors and changes that affected them.

Community participation helps ensure that the knowledge gained from this project is accurate and relevant to the community. Conducting this research with community participation provides unique information about adaptation to significant trauma and change that is difficult to learn elsewhere. Yet it also provides information applicable to other rural indigenous communities undergoing stress and change. Therefore, this culturally specific knowledge, and the intervention it helps to inform, will be useful both in the local communities it is developed in, as well as more broadly. It can help inform the process of future community collaborations to develop culturally appropriate interventions, and strategies for addressing stress in indigenous communities undergoing rapid cultural change. It is clear that each of these contributions of CBPR adds value to our science making it more accurate, relevant and allowing us access to the internal worldview and perspectives of a minority group experiencing significant health disparities.

Conclusion

This process paper illustrates the challenges to conducting CBPR in rural Alaska Native communities, how these challenges were addressed in the current project, the value of community partnerships, and lessons learned to nurture community partnership throughout the research process. Community participation was critical in the development and implementation of measures for the Stress and Coping project, and will continue to be critical in interpretation and use of findings, helping to ensure that the resulting stress management program draws on community strengths and resources, that barriers to intervention implementation are addressed with sensitivity, that the intervention is targeted at appropriate social-ecological levels, and that it aptly manages the complicated factors that impact stress, coping, and community health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) grant No. 2 P20 RR016430-06A1 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). We wish to thank the collaborating partners, including the communities who we partnered with, and the YKHC. We also wish to acknowledge the CANHR research team. Finally, we wish to acknowledge the research participants who shared their experiences. Without them this research would not be possible.

References

- Alaska Federation of Natives. Principles for the conduct of research in the Arctic. Retrieved November 23 2009, from http://ankn.uaf.edu/IKS/conduct.html.

- Alaska Injury Prevention Center, Critical Illness and Trauma Foundation Inc., & American Society for Suicidology. Alaska Suicide Follow-back Study Final Report. Anchorage, AK: 2007. p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- American Indian Law Center. Model Tribal Research Code. (3) 1999 Retrieved November 23, 2009, from http://www.ihs.gov/medicalprograms/research/pdf_files/mdl-code.pdf.

- Bersamin A, Luick BR, King IB, Ruppert E, Stern JS, Zidenberg-Cherr S. Westernizing diets influence fat intake, red blood cell fatty acid composition, and health in remote Alaska Native communities in the Center for Alaska Native Health Research Study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2008;108(2):266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer BB, Mohatt GV, Lardon C, Plaetke R, Luick BL, Hutchison SH, et al. Building a community-based participatory research center to investigate obesity and diabetes in Alaska Natives. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2005;64(3):281–290. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v64i3.18002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burhansstipanov L, Christopher S, Schumacher SA. Lessons learned from community-based participatory research in Indian country. Cancer Control: Journal Of The Moffitt Cancer Center. 2005;12(Suppl 2):70–76. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004s10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CANHR. Center for Alaska Native Health Reseach (CANHR Home) 2009 Retrieved December 9, 2009, from http://canhr.uaf.edu/

- Casillas DM. Unpublished master’s thesis. University of South Dakota; Vermillion, SD: 2006. Evolving research approaches in tribal communities: A community empowerment training. [Google Scholar]

- Chino M, DeBruyn L. Building true capacity Indigenous models for indigenous communities. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(4):596–599. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran PAL, Marshall CA, Garcia-Downing C, Kendall E, Cook D, McCubbin L, et al. Indigenous ways of knowing: Implications for participatory research and community. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):22–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinges NG, Joos SK. Stress, coping, and health: Models of interaction for Indian and Native populations. American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research, Monograph No 1. 1988:8–64. doi: 10.5820/aian.mono01.1988.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BS. Social stress and community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1978;6(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00890095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran E, Duran B. Native American postcolonial psychology. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Hoagwood K, Boyce C, Duster T, Frank DA, Grisso T, et al. Research ethics for mental health science involving ethnic minority children and youths. American Psychologist. 2002;57(12):1024–1040. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.12.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Ball TJ. Balancing empiricism and local cultural knowledge in the design of prevention research. Journal of Public Health. 2005;82(2 (supplement 3)):iii44–iii54. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(6):823–865. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823. Literature Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith S, Angvik J, Howe L, Hill A, Leask L, Saylor B, et al. The status of Alaska Natives report 2004. 2004;I [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EH, Cummins LH, Marlatt GA. Preventing sustance abuse in American Indian and Alaska Native youth: Promising strategies for healthier communities. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:304–323. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. The ecology of stress. Washington, DC US: Hemisphere Publishing Corp; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assesing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19(19):173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Keys CB, Suarez-Balcazar Y, Taylor RR, Davis MI. Participatory community research: Theories and methods in action. Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;35(1):2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise TD, Medoff L, Lee CC, Harris A. Psychosocial and cultural correlates of suicidal ideation among American Indian early adolescents on a northern plains reservation. Research in Human Development. 2007;4(1):119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lanier AP, Kelly JJ, Maxwell J, McEvoy T, Homan C. Cancer in Alaska Native people, 1969-2003. Alaska Medicine. 2006;48(2):30–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardon C, Drew EM, Kernak D, Lupie H, Soule S. Health promotion in rural Alaska: Building partnerships across distance and cultures. Partnership Perspectives. 2007;6(1):125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM. The wounded spirit: A cultural formulation of post-traumatic stess disorder. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1996;20:489–498. doi: 10.1007/BF00117089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Beals J, Klein SA, Croy CD. Social epidemiology of trauma among 2 American Indian reservation populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(5):851–859. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Bechtold D, Novins DK, Beals J. Assessing psychopathology in America Indian and Alaska Native children and adolescents. National Center for American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: Applied Development Science. 1997;1:135–144. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Seminars in Medicine of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center: Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(3):171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Seeman T. Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress. Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;896:30–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Stellar E. Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1993;153(18):2093–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Hazel KL, Allen JR, Hensel C, Stachelrodt M, Fath R. Unheard Alaska: Participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33(3):263–273. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027011.12346.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Thomas L, Allen J, Hazel K, Hensel C, et al. Tied together like a woven hat: Protective pathways to sobriety for Alaska Natives. Harm Reduction Journal. 2004;1(10) doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Thomas LR . the People Awakening Team. “I wonder, why would you do it that way?” Ethical dilemmas in doing participatory research with Alaska Native communities. In: Trimble JE, Fisher CB, editors. Handbook of Ethical Research with Ethnocultural Populations and Communities. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs (OPP) Principles for the conduct of research in the Arctic. 2006 Retrieved November 23, 2009, from http://www.nsf.gov/od/opp/arctic/conduct.jsp.

- Noe TD, Manson SM, Croy C, McGough H, Henderson JA, Buchwald DS. The influence of community-based participatory research principles on the likelihood of participation in health research in American Indian communities. Ethnicity & Disease. 2007;17(1):6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31(6):539–548. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90105-4. Empirical Study. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering T. Cardiovascular pathways: socioeconomic status and stress effects on hypertension and cardiovascular function. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;896:262–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek JT, Smith RE, Espe K, Raffety B. Limited correspondence between daily coping reports and restrospective coping recall. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(1):41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Robin RW, Chester B, Goldman D. Cumulative trauma and PTSD in American Indian communities. In: Marsella AJ, Friedman MJ, Gerrity ET, Scurfield RM, editors. Ethnocultural aspects of posttraumatic stress disorder: Issues, research, and clinical applications. Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association; 1996. pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Stiffman AR, Freedenthal S, Brown E, Ostmann E, Hibbeler P. Field research with underserved minorities: The ideal and the real. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2005;82(2):Iii56–Iii66. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Neale JM, Marco CA, Shiffman S, Hickcox M, et al. A comparison of coping assessed by ecological momentary assessment and retrospective recall. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1998;74(6):1670–1680. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Repetti RL, Seeman T. Health psychology: What is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin? Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:411–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice DM, Bratslavsky E, Baumeister RF. Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80(1):53–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ, Birman D. Taking ecology seriously: A community development approach to individually based preventive interventions in schools. In: Bond LA, Compas BE, editors. Primary prevention and promotion in the schools. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1989. pp. 361–390. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ, Espino SL. Collaboration and social inquiry: Multiple meanings of a construct and its role in creating useful and valid knowledge. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;34(1-2):1–69. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000040146.32749.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimble JE. Commentary: No itinerant researchers tolerated: Principled and ethical perspectives and research with North American Indian communities. Ethos. 2009a;36(3):379–382. [Google Scholar]

- Trimble JE. The principled conduct of counseling research with ethnocultural populations: The influence of moral judgments on scientific reasoning. In: Ponterotto J, Casas JM, Suzuki L, Alexander CM, editors. Handbook of multicultural counseling. third edition. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 2009b. pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Trimble JE, Fisher CB, editors. Handbook of ethical research with ethnocultural populations and communities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Trimble JE, Scharron-del Rio M, Bernal G. The itinerant researcher: Ethical and methodological issues in conducting cross-cultural mental health research. In: Jack DC, Ali A, editors. Silencing the self across cultures: Depression and gender in the social world. New York: Oxford University; 2010. pp. 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich PM, Lutgendorf SK. Journaling about stressful events: Effects of cognitive processing and emotional expression. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24(3):244–250. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_10. Empirical Study. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM. Reconceptualizing Native women’s health: An “indigenist” stress-coping model. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):520–524. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell T. Substance use among American Indians and Alaskan Natives: Incorporating culture in an “indigenist” stress-coping paradigm. Public Health Report. 2002;177(Supp. 1):S104–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L. Inupiat youth suicide and culture loss: Changing community conversations for prevention. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(11):2938–2948. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler L, Reis HT. Self-recording of everyday life events - origins, types, and uses. Journal of Personality. 1991;59(3):339–354. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KG, Stelzer J, Bergman JN, Kral MJ, Inayatullah M, Elliott CA. Problem solving, stress, and coping in adolescent suicide attempts. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 1995;25(2):12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolsko C, Lardon C, Hopkins S, Ruppert E. Conceptions of wellness among the Yup’ik of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta: The vitality of social and natural connection. Ethnicity and Health. 2006;11(4):345–363. doi: 10.1080/13557850600824005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolsko C, Lardon C, Mohatt GV, Orr E. Stress, coping, and well-being among the Yup’ik of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta: The role of enculturation and acculturation. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2007;66(1):51–61. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i1.18226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation. Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation. website Retrieved November 23, 2009, from http://www.ykhc.org/