Abstract

Calcium (Ca2+) is a universal second messenger that regulates a number of diverse cellular processes including cell proliferation, development, motility, secretion, learning and memory1, 2. A variety of stimuli, such as hormones, growth factors, cytokines, and neurotransmitters induce changes in the intracellular levels of Ca2+. The most ubiquitous and abundant protein that serves as a receptor to sense changes in Ca2+ concentrations is Calmodulin (CaM), thus mediating the role as second messenger of this ion. The Ca2+/CaM complex initiates a plethora of signaling cascades that culminate in alteration of cell functions. Among the many Ca2+/CaM binding proteins, the multifunctional protein kinases CaMKII and CaMKIV play pivotal roles in the cell.

Keywords: calcium, cell signaling, kinase, proliferation

I. INTRODUCTION

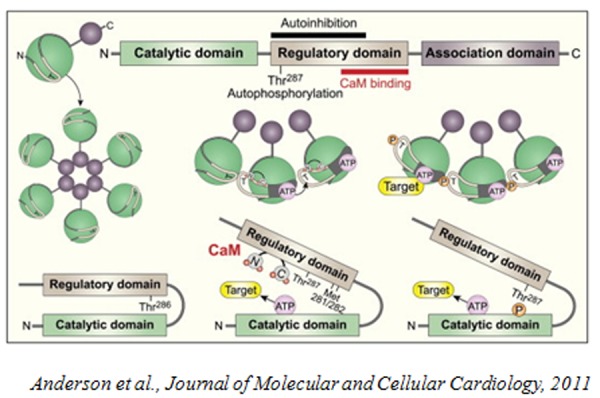

The general structure of CaMKs includes an N-terminal kinase domain, an autoregulatory domain, an overlapping CaM-binding domain and, in phosphorylase kinase and CaMKII, a C-terminal association domain that is essential for multimerization and targeting.

The best characterized CaM Kinase is CaMKII3. CaMKII is a multimeric enzyme composed of 12 subunits and it is encoded by 4 separate genes (α, β, γ, δ) with at least 24 peptides generated by alternate splicing4, 5 and at least one isoform expressed in every cell type6. CaMKII has a distinct mechanism of regulation that differs from the others CaM kinases. One catalytic subunit phosphorylates the autoinhibitory domain of the adjacent subunit on T286 (in the α isoform). This event requires that both the catalytic subunit and the substrate subunit are bound to Ca2+/CaM7, 8. T286 phosphorylation then results in 20–80% Ca2+/CaM-independent activity4,9–13. Autophosphorylation of T286 increases affinity for CaM by decreasing the rate of CaM dissociation. CaM is trapped by autophosphorylation, so that even when Ca2+ levels are reduced, the kinase is fully active until CaM dissociates (several hundreds of seconds13). This could serve as a mechanism to increase the sensitivity of CaMKII to the changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration7, 13.

Anderson et al., Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 2011

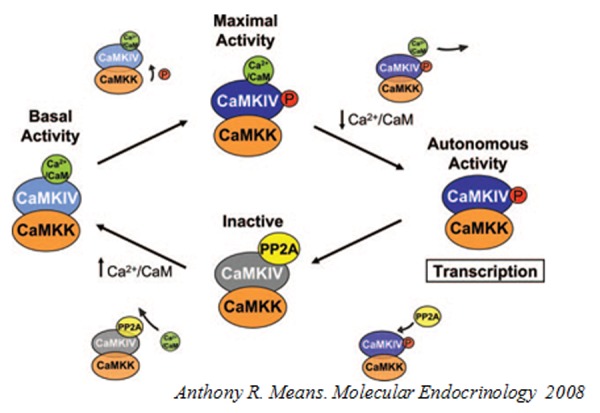

CaMKIV is a serine/threonine protein kinase that has been localized also in the nucleus14. Its expression is tissue-specific, with expression restricted primarily to distinct regions of the brain, T-lymphocytes, and postmeiotic germ cells,15, 16 although it has been found in other cell types 17, being especially enriched in cerebellar granule cells. CaMKIV (one gene, two splice variants)18 – is a monomeric enzyme, and apart from activation by Ca2+/CaM, shows very different modes of regulation by phosphorylation compared to CaMKII. CaMKIV has an “activation loop” phosphorylation site that is absent in CaMKII. Binding of Ca2+/CaM to CaMKIV exposes this activation loop site to allow phosphorylation by the upstream CaMKK, when it is simultaneously activated by Ca2+/CaM19. Phosphorylation of the activation loop in CaMKIV primarily increases its Ca2+/CaM-dependent activities.

Anthony R. Means. Molecular Endocrinology 2008

II. CaMK-MEDIATED ACTIVATION OF TRANSCRIPTION

CaMKII and CREB

As CaM kinases II and IV have quite similar substrate specificity determinants, it is not completely surprising that they sometimes phosphorylate the same proteins. One such in vitro substrate for these kinases is the cAMP-response element binding protein, CREB. CaMKII can phosphorylate CREB at Ser133 residue leading to the speculation that CaMKII mediates the Ca2+ requirement for expression of the immediate early genes5. However, while the truncated form of CaMKII can stimulate CREB-mediated transcription in some cells, it is inhibitory in others. Sun et al. 20 discovered that in addition to Ser-133, CaMKII also phosphorylated a second residue on CREB, Ser-142. Indeed, phosphorylation of Ser-142 was not only inhibitory, but this modification was also dominant and could reverse the activation of CREB resulting from its phosphorylation on Ser-133 by PKA. This phosphorylation seems to be destabilizing for the association between CREB and CBP21. Interestingly, the nature of the effect of CaMKII on transcription is both cell and promoter dependent.

CaMKIV AND CREB

CaMKIV shows very strong nuclear localization22, 23, and many studies support the idea that it is responsible for Ca2+-dependent stimulation of transcription through phosphorylation of CREB and serum response factor (SRF)5, 22, 24. Activation by CaMKIV occurs via direct phosphorylation of the activating serines of these transcription factors, Ser133 (CREB), Ser63 (ATF-1), and Ser103(SRF), respectively25. CaMKIV phosphorylates CREB Ser133, the same site that is phosphorylated by PKA. Transfected CaMKIV alone is a relatively poor stimulator of transcriptional activation by CREB: indeed, cotransfection of CaMKK with CaMKIV gives a 14-fold enhancement of transcription26. Studies in cultured hippocampal neurons indicate that CaMKIV regulates CREB-dependent gene transcription in response to electrical stimulation or KCl depolarization27. This role of CaMKIV in CREB-mediated transcription has been confirmed in transgenic mice that express an inactive form of CaMKIV only in T cells in the thymus27. Overexpression of inactive CaMKIV would be expected to function in a dominant negative manner. These thymic T cells have a reduced ability, upon stimulation, to phosphorylate CREB, induce transcription of FosB and produce interleukin 2 (IL-2)28. There is also good evidence for involvement of CaMKIV in transcriptional regulation of the BDNF gene through phosphorylation of a CREB family member29.

These observations provide a mechanism that would permit the Ca2+ signaling pathway to be either antagonistic or additive with the cAMP pathway for activation of CREB, depending on the relative activity of specific CaM kinases.

III. CaMKs MEDIATED REGULATION OF APOPTOSIS

Bok et al30 observed that CaMKII promotes SGN survival, at least in part, by functionally inactivating Bad. The ability of Bad to move from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria, where it can carry out its pro-apoptotic function, is regulated by phosphorylation 31, 32. Thus, Bad plays a central role in the regulation of apoptosis. CaMKII also regulates apoptosis by inactivating Bad. One phosphorylation site on Bad, Ser17033, is a potential CaMKII target, raising the possibility that CaMKII phosphorylates Bad directly. However, co-expression of Bad and truncated form of CaMKII(1–290) in PC12 cells results in Bad hyper-phosphorylation, including phosphorylation of Ser112. This implies an indirect pathway for Bad phosphorylation by CaMKII. The mechanism by which CaMKII inactivates Bad involves multiple signaling pathways, and differs among cell types. CaMKII also suppresses nuclear translocation of histone deacetylase, thereby promoting neuronal survival34. Indeed, CaMKII has been shown to activate the pro-survival transcriptional regulator NF-κB in T lymphocytes and in neurons35. Because dominant-negative CREB constructs do not reduce the pro-survival effect of CaMKII, it is unlikely that CREB is the nuclear target of CaMKII. The depolarization also promotes survival by recruiting a nuclear pathway involving CaMKIV and CREB30. This is supported by the observations that dominant-inhibitory CaMKIV and dominant-inhibitory CREB both reduce the ability of depolarization to promote survival and dominant-inhibitory CREB blocks the ability of CaMKIV to promote survival. They also used a constitutively-active CREB mutant, CREBDIEDML, and found that it failed to support SGN survival. Probably the level of transcriptional activation given by CREBDIEDML is insufficient to promote survival. Alternatively, recruitment of CBP by CREB is necessary but is not sufficient for promotion of survival via CREB-dependent gene expression.

IV. CaMKs MEDIATED REGULATION OF PROLIFERATION

Cell proliferation is regulated by converging signals on the cell cycle machinery that determine whether the cell stays in the G1 phase or proceeds to S phase. The progression through G1 into the DNA synthesizing S phase is driven by cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)4 and CDK6, that interact with the cyclin D family of proteins, and CDK2, that interacts with cyclins A/E 36. The Ras/Raf/Mek/Erk cascade plays a pivotal role in the control of this process: indeed, sustained Erk activation is required to pass the G1 restriction point and regulate cyclin D1 expression during mid-G1 phase 37, 38. CaMKII plays a pivotal role in the modulation of Erk activation in a number of cell models. A crosstalk between CaMKII and Erk pathway was first demonstrated in response to cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix in thyroid cells. CaMKII participates to Raf1 activation and controls Erk phosphorylation following integrin stimulation by fibronectin 39, 40. Indeed, the link between Ca2+ signaling and the ERK pathway has been documented 38, 41: ERK is activated by a CaMKII and Raf-dependent mechanism 42, and CaMKII facilitates adhesion-dependent activation of ERK in VSMCs 41, 43. CaM antagonist or CaMKII inhibitors attenuate ERK activation in response to several stimuli 44, and coexpression of CaMKII or a CaMKII inactive mutant in CHO cells down-regulates Ca2+-induced ERK activation 15, 45. These data suggest that CaMKII and ERK are essential mediators of cell proliferation 46, 47. The role of CaMKII in cell proliferation is not a restricted mechanism, but it is a general phenomenon that may be relevant for the biological effects of many growth factors and hormones.

V. CaMKs MEDIATED REGULATION OF DIFFERENTIATED FUNCTIONS

SURVIVAL

The multifunctional CaMKs family proteins are involved in the control of differentiation and survival of neurons and hematopoietic stem cells 48. In the cerebellum, granule and Purkinje cells (PCs) develop synergistically, and alterations in the developmental program of either cell type affects the other 45. Many studies showed that the absence of CaMKIV results in abnormal PCs, characterized by a decreased number of mature cells together with stunted arborization and altered parallel fiber synaptic currents of the remaining cells 21, 49. Kobubo et al hypothesized that these adult defects may arise from developmental issues involving CGCs in addition to PCs. These cells only express CaMKIV during a briefperiod between late embryogenesis and early postnatal development, whereas CGCs express both CaMKIV and its upstream activator CaMKK2 from early postnatal development through adulthood 50 .CaMKIV exert prosurvival functions. Inneurons, BDNF signaling through TrKB inhibits apoptosis through the MAP and PI-3 kinase/AKT pathways 15. CaMKIV has a prosurvival role in multiple cell types including hematopoietic stem cells(HSCs) 51, and dendritic cells 52.

Kitsos

The hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) gives rise to all mature, terminally differentiated cells of the blood. CaMKIV is involved in early hematopoietic development, and the absence of CaMKIV results in a reduction in the number of c-Kit+ScaI+Lin−/low cells (KLScells), a cell population that includes long-term and short term hematopoietic stem cells as well as other multipotent progenitor cells 53. Camk4 gene is expressed in KLS cells, and CaMKIV is required for KLS cells to repopulate the bone marrow in transplantation assays. Camk4−/−KLS cells display enhanced proliferation as well as increased apoptosis, in vivo and in vitro, compared with wild type (WT) cells and have decreased levels of phospho-CREB (pCREB), CBP, Bcl-2 mRNA and Bcl-2 protein. Re-expression of CaMKIV in Camk4−/−KLS cells restores Bcl-2 and CBP levels and rescues the proliferation defects.

Many critical biological functions involve Ca2+ signaling in DC. For example, apoptotic body engulfment and processing are accompanied by a rise in intracellular Ca2+ and are dependent on external Ca2+ 54. In addition, chemotactic molecules produce Ca2+ increases in DC, 55 suggesting the involvement of a Ca2+-dependent pathway in the regulation of DC migration. The role of a Ca2+-dependent pathway in the mechanism regulating DC maturation is suggested by the opposite effects induced by Ca2+ ionophores or chelation of extracellular Ca2+ on this process56. The pharmacologic inhibition of CaMKs as well as ectopic expression of kinase-inactive CaMKIV decrease the viability of monocyte-derived DCs exposed to bacterial LPS. Although isolated Camk4 / DCs are able to acquire the phenotype typical of mature cells and release normal amounts of cytokines in response to LPS, they fail to accumulate pCREB, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL and therefore do not survive.

CARDIAC HYPERTROPHY

CaMKII has been implicated in several key aspects of acute cellular Ca2+ regulation related to cardiac excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling. CaMKII phosphorylates sarcoplasmic reticulum57 proteins, including the ryanodine receptors (RyR2) and phospholamban (PLB)57. Contractile dysfunction develops with hypertrophy, characterizes heart failure, and is associated with changes in cardiomyocyte Ca2+ homeostasis 58. CaMKII expression and activity are altered in the myocardium of rat models of hypertensive cardiac hypertrophy59 and heart failure 60, and in cardiac tissue from patients with dilated cardiomyopathy61. Several transgenic mouse models have confirmed a role for CaMK in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertrophy develops in transgenic mice that overexpress CaMKIV 62, but this isoform is not detectable in the heart and CaMKIV knockout mice still develop hypertrophy following transverse aortic constriction (TAC) 63. CaMKII regulates expression of several hypertrophic marker genes, including ANF64 BNP65, h-MHC66 and a-skeletal actin61. The nuclear localization signal of CaMKIIδB was shown to be required for this hypertrophic response, as transfection of CaMKIIδC did not result in enhanced ANF expression67, 68. MEF2 has been suggested to act as a common endpoint for hypertrophic signaling pathways in the myocardium,66 and studies using CaMKIV transgenic mice crossed with MEF2 indicator mice suggest that MEF2 is a downstream target for CaMKIV 69. Recent studies have demonstrated that MEF2 can interact with class II histone deacetylases (HDACs), a family of transcriptional repressors, as well as with other repressors that limit MEF2-dependent gene expression. Notably, constitutively activated CaMKIV have been shown to activate MEF2 by phosphorylating and dissociating HDACs, leading to its subsequent nuclear export 70.

VI. CaMKs AND INFLAMMATION

Sepsis is a special type of host inflammatory response to bacterial infection that originates from massive and widespread release of pro-inflammatory mediators. Bacterial endotoxins, such as LPS, are the major offending factors in sepsis that activate TLR-mediated signaling to generate inflammatory response that is amplified in a self-sustaining manner. There are meny evidences of a correlation between multifunctional CaM kinases and TLR-4 signaling. CaMKII directly phosphorylates components of TLR signaling, and promotes cytokine production in macrophages71. Complement activation is also a recognized factor in the pathogenesis of sepsis. Inhibition of the complement cascade decreases inflammation and improves mortality in animal models51. Differentiation and survival of antigen presenting dendritic cells (DC) uponTLR-4 activation requires CaMKIV72. DC from CaMKIV−/−mice failed to survive upon LPS-mediated TLR-4 induction. However, ectopic expression of CaMKIV was able to rescue this defect. In another study, the selective inhibition of CaMKII interfered with terminal differentiation of monocyte-derived DCs by preventing up-regulation of co-stimulatory and MHC II molecules as well as secretion of cytokines induced by TLR-4 agonists73. Thus, CaM kinases seem to play a general role in inflammatory processes

VII. CONCLUSIONS

CaMKs define a family of ser-thr kinases that direct a wide range of cellular processes and cell fate decisions. Since their discovery, much of the focus has been on their regulation of memory and learning. In recent years, studies on CaMKII and CaMKIV signaling in a number of cell models have established the importance of the Ca2+-CaM-CaMKK-CaMKs pathways in effecting proliferation, survival, differentiation and associated molecular events. Intriguing new findings also indicate that, although the two kinases might share some substrates, there is specificity in the pathways they contribute, thus reflecting both shared and unique properties. The emergence of ERK as a critical CaMKII regulatory target for cell proliferation has united membrane proximal regulatory events orchestrated by the Ras activated cascade with key transcriptional CaMKs targets.

Ca2+ is ubiquitously present in the cells, hence its compartimentalization and the regulation of its downstream kinases need to be finely tuned, in order to efficiently regulate biological functions. The involvement of CaMKII and CaMKIV in pathways that regulate functions as different as proliferation, survival and differentiation imply numerous cross-talks and their harmonization. Both kinases require Ca2+ increases to be activated, although other events are required to support their differential activation. Subcellular compartimentalization provides another tool to distinctively activate CaMKII and CaMKIV depending upon the cell’s needs. It is possible, though, to hypothesize a further mechanism of counter-regulation between the two kinases: insights into the regulation and impact of a crosstalk between CaMKII and CaMKIV signaling might bring in new highlights for biological functions, and their disruption in human diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carafoli E. Calcium signaling: a tale for all seasons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1115–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032427999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun AP, Schulman H. The multifunctional calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase: from form to function. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:417–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hook SS, Means AR. Ca(2+)/CaM-dependent kinases: from activation to function. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:471–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun P, Enslen H, Myung PS, Maurer RA. Differential activation of CREB by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases type II and type IV involves phosphorylation of a site that negatively regulates activity. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2527–39. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walke W, Staple J, Adams L, Gnegy M, Chahine K, Goldman D. Calcium-dependent regulation of rat and chick muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19447–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanson PI, Meyer T, Stryer L, Schulman H. Dual role of calmodulin in autophosphorylation of multifunctional CaM kinase may underlie decoding of calcium signals. Neuron. 1994;12:943–56. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukherji S, Soderling TR. Mutational analysis of Ca(2+)-independent autophosphorylation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14062–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.14062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong YL, Taylor WL, Means AR, Soderling TR. Studies of the regulatory mechanism of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Mutation of threonine 286 to alanine and aspartate. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16759–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanson PI, Kapiloff MS, Lou LL, Rosenfeld MG, Schulman H. Expression of a multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase and mutational analysis of its autoregulation. Neuron. 1989;3:59–70. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fong YL, Soderling TR. Studies on the regulatory domain of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Functional analyses of arginine 283 using synthetic inhibitory peptides and site-directed mutagenesis of the alpha subunit. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11091–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waldmann R, Hanson PI, Schulman H. Multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase made Ca2+ independent for functional studies. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1679–84. doi: 10.1021/bi00459a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer T, Hanson PI, Stryer L, Schulman H. Calmodulin trapping by calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Science. 1992;256:1199–202. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Means AR, Cruzalegui F, LeMagueresse B, Needleman DS, Slaughter GR, Ono T. A novel Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase and a male germ cell-specific calmodulin-binding protein are derived from the same gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3960–71. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitsos CM, Sankar U, Illario M, Colomer-Font JM, Duncan AW, Ribar TJ, Reya T, Means AR. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV regulates hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33101–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang SL, Ribar TJ, Means AR. Expression of Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (caMKIV) messenger RNA during murine embryogenesis. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12:351–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wayman GA, Tokumitsu H, Davare MA, Soderling TR. Analysis of CaM-kinase signaling in cells. Cell Calcium. 50:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokumitsu H, Soderling TR. Requirements for calcium and calmodulin in the calmodulin kinase activation cascade. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5617–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheng M, Thompson MA, Greenberg ME. CREB: a Ca(2+)-regulated transcription factor phosphorylated by calmodulin-dependent kinases. Science. 1991;252:1427–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1646483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker D, Jhala US, Radhakrishnan I, Yaffe MB, Reyes C, Shulman AI, Cantley LC, Wright PE, Montminy M. Analysis of an activator:coactivator complex reveals an essential role for secondary structure in transcriptional activation. Mol Cell. 1998;2:353–9. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen KF, Ohmstede CA, Fisher RS, Olin JK, Sahyoun N. Acquisition and loss of a neuronal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase during neuronal differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:4050–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enslen H, Soderling TR. Roles of calmodulin-dependent protein kinases and phosphatase in calcium-dependent transcription of immediate early genes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:20872–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthews RP, Guthrie CR, Wailes LM, Zhao X, Means AR, McKnight GS. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase types II and IV differentially regulate CREB-dependent gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6107–16. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun P, Lou L, Maurer RA. Regulation of activating transcription factor-1 and the cAMP response element-binding protein by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases type I, II, and IV. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3066–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tokumitsu H, Enslen H, Soderling TR. Characterization of a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascade. Molecular cloning and expression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19320–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bito H, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW. CREB phosphorylation and dephosphorylation: a Ca(2+)- and stimulus duration-dependent switch for hippocampal gene expression. Cell. 1996;87:1203–14. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81816-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson KA, Ribar TJ, Illario M, Means AR. Defective survival and activation of thymocytes in transgenic mice expressing a catalytically inactive form of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:725–37. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shieh PB, Hu SC, Bobb K, Timmusk T, Ghosh A. Identification of a signaling pathway involved in calcium regulation of BDNF expression. Neuron. 1998;20:727–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Impey S, Fong AL, Wang Y, Cardinaux JR, Fass DM, Obrietan K, Wayman GA, Storm DR, Soderling TR, Goodman RH. Phosphorylation of CBP mediates transcriptional activation by neural activity and CaM kinase IV. Neuron. 2002;34:235–44. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bok J, Wang Q, Huang J, Green SH. CaMKII and CaMKIV mediate distinct prosurvival signaling pathways in response to depolarization in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;36:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.del Peso L, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Page C, Herrera R, Nunez G. Interleukin-3-induced phosphorylation of BAD through the protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;278:687–9. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang X, Yu S, Eder A, Mao M, Bast RC, Jr, Boyd D, Mills GB. Regulation of BAD phosphorylation at serine 112 by the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Oncogene. 1999;18:6635–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linseman DA, Bartley CM, Le SS, Laessig TA, Bouchard RJ, Meintzer MK, Li M, Heidenreich KA. Inactivation of the myocyte enhancer factor-2 repressor histone deacetylase-5 by endogenous Ca(2+) //calmodulin-dependent kinase II promotes depolarization-mediated cerebellar granule neuron survival. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41472–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Midorikawa R, Takei Y, Hirokawa N. KIF4 motor regulates activity-dependent neuronal survival by suppressing PARP-1 enzymatic activity. Cell. 2006;125:371–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherr CJ. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell. 1994;79:551–5. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welsh CF, Roovers K, Villanueva J, Liu Y, Schwartz MA, Assoian RK. Timing of cyclin D1 expression within G1 phase is controlled by Rho. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:950–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Illario M, Cavallo AL, Bayer KU, Di Matola T, Fenzi G, Rossi G, Vitale M. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II binds to Raf-1 and modulates integrin-stimulated ERK activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:45101–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Illario M, Cavallo AL, Monaco S, Di Vito E, Mueller F, Marzano LA, Troncone G, Fenzi G, Rossi G, Vitale M. Fibronectin-induced proliferation in thyroid cells is mediated by alphavbeta3 integrin through Ras/Raf-1/MEK/ERK and calcium/CaMKII signals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2865–73. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abraham ST, Benscoter HA, Schworer CM, Singer HA. A role for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade of cultured rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1997;81:575–84. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ginnan R, Singer HA. CaM kinase II-dependent activation of tyrosine kinases and ERK1/2 in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C754–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00335.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tebar F, Llado A, Enrich C. Role of calmodulin in the modulation of the MAPK signalling pathway and the transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor mediated by PKC. FEBS Lett. 2002;517:206–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu KK, Armstrong SE, Ginnan R, Singer HA. Adhesion-dependent activation of CaMKII and regulation of ERK activation in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1343–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00064.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cipolletta E, Monaco S, Maione AS, Vitiello L, Campiglia P, Pastore L, Franchini C, Novellino E, Limongelli V, Bayer KU, Means AR, Rossi G, et al. Calmodulin-dependent kinase II mediates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and is potentiated by extracellular signal regulated kinase. Endocrinology. 151:2747–59. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Della Rocca GJ, Maudsley S, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ, Luttrell LM. Pleiotropic coupling of G protein-coupled receptors to the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Role of focal adhesions and receptor tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13978–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ribar TJ, Rodriguiz RM, Khiroug L, Wetsel WC, Augustine GJ, Means AR. Cerebellar defects in Ca2+/calmodulin kinase IV-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC107. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-j0004.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Monaco S, Illario M, Rusciano MR, Gragnaniello G, Di Spigna G, Leggiero E, Pastore L, Fenzi G, Rossi G, Vitale M. Insulin stimulates fibroblast proliferation through calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinase II. Cell cycle. 2009;8:2024–30. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.13.8813. (Georgetown, Tex. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rusciano MR, Salzano M, Monaco S, Sapio MR, Illario M, De Falco V, Santoro M, Campiglia P, Pastore L, Fenzi G, Rossi G, Vitale M. The Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase II is activated in papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) and mediates cell proliferation stimulated by RET/PTC. Endocrine-related cancer. 17:113–23. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrison ME, Mason CA. Granule neuron regulation of Purkinje cell development: striking a balance between neurotrophin and glutamate signaling. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3563–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03563.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohmstede CA, Jensen KF, Sahyoun NE. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase enriched in cerebellar granule cells. Identification of a novel neuronal calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5866–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng F, Soellner D, Nunez J, Wang H. The basal level of intracellular calcium gates the activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt signaling by brain-derived neurotrophic factor in cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1259–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Illario M, Giardino-Torchia ML, Sankar U, Ribar TJ, Galgani M, Vitiello L, Masci AM, Bertani FR, Ciaglia E, Astone D, Maulucci G, Cavallo A, et al. Calmodulin-dependent kinase IV links Toll-like receptor 4 signaling with survival pathway of activated dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;111:723–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morrison SJ, Wandycz AM, Hemmati HD, Wright DE, Weissman IL. Identification of a lineage of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Development. 1997;124:1929–39. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.10.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rubartelli A, Poggi A, Zocchi MR. The selective engulfment of apoptotic bodies by dendritic cells is mediated by the alpha(v)beta3 integrin and requires intracellular and extracellular calcium. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1893–900. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan VW, Weisbrod MJ, Kaszas Z, Dragomir C. Comparison of ropivacaine and lidocaine for intravenous regional anesthesia in volunteers: a preliminary study on anesthetic efficacy and blood level. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1602–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199906000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Czerniecki BJ, Carter C, Rivoltini L, Koski GK, Kim HI, Weng DE, Roros JG, Hijazi YM, Xu S, Rosenberg SA, Cohen PA. Calcium ionophore-treated peripheral blood monocytes and dendritic cells rapidly display characteristics of activated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:3823–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Misra RP, Bonni A, Miranti CK, Rivera VM, Sheng M, Greenberg ME. L-type voltage-sensitive calcium channel activation stimulates gene expression by a serum response factor-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25483–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maier LS, Bers DM. Calcium, calmodulin, and calcium-calmodulin kinase II: heartbeat to heartbeat and beyond. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:919–39. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boknik P, Heinroth-Hoffmann I, Kirchhefer U, Knapp J, Linck B, Luss H, Muller T, Schmitz W, Brodde O, Neumann J. Enhanced protein phosphorylation in hypertensive hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;51:717–28. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Netticadan T, Temsah RM, Kawabata K, Dhalla NS. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase is altered in heart failure. Circ Res. 2000;86:596–605. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kirchhefer U, Schmitz W, Scholz H, Neumann J. Activity of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in failing and nonfailing human hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:254–61. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramirez MT, Zhao XL, Schulman H, Brown JH. The nuclear deltaB isoform of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates atrial natriuretic factor gene expression in ventricular myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31203–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colomer JM, Mao L, Rockman HA, Means AR. Pressure overload selectively up-regulates Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:183–92. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gruver CL, DeMayo F, Goldstein MA, Means AR. Targeted developmental overexpression of calmodulin induces proliferative and hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes in transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 1993;133:376–88. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.1.8319584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.He Q, LaPointe MC. Interleukin-1beta regulates the human brain natriuretic peptide promoter via Ca(2+)-dependent protein kinase pathways. Hypertension. 2000;35:292–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu W, Zou Y, Shiojima I, Kudoh S, Aikawa R, Hayashi D, Mizukami M, Toko H, Shibasaki F, Yazaki Y, Nagai R, Komuro I. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II and calcineurin play critical roles in endothelin-1-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15239–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Passier R, Zeng H, Frey N, Naya FJ, Nicol RL, McKinsey TA, Overbeek P, Richardson JA, Grant SR, Olson EN. CaM kinase signaling induces cardiac hypertrophy and activates the MEF2 transcription factor in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1395–406. doi: 10.1172/JCI8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kolodziejczyk SM, Wang L, Balazsi K, DeRepentigny Y, Kothary R, Megeney LA. MEF2 is upregulated during cardiac hypertrophy and is required for normal post-natal growth of the myocardium. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1203–6. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lu J, McKinsey TA, Nicol RL, Olson EN. Signal-dependent activation of the MEF2 transcription factor by dissociation from histone deacetylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4070–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080064097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blaeser F, Ho N, Prywes R, Chatila TA. Ca(2+)-dependent gene expression mediated by MEF2 transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:197–209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davis FJ, Gupta M, Camoretti-Mercado B, Schwartz RJ, Gupta MP. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase activates serum response factor transcription activity by its dissociation from histone deacetylase, HDAC4. Implications in cardiac muscle gene regulation during hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20047–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209998200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huber-Lang MS, Riedeman NC, Sarma JV, Younkin EM, McGuire SR, Laudes IJ, Lu KT, Guo RF, Neff TA, Padgaonkar VA, Lambris JD, Spruce L, et al. Protection of innate immunity by C5aR antagonist in septic mice. Faseb J. 2002;16:1567–74. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0209com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herrmann TL, Morita CT, Lee K, Kusner DJ. Calmodulin kinase II regulates the maturation and antigen presentation of human dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1397–407. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0205105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Singh MV, Anderson ME. Is CaMKII a link between inflammation and hypertrophy in heart? J Mol Med (Berl) 89:537–43. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0727-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]