Abstract

Pheochromocytomas have been described in association with rare vascular abnormalities, most common of them being renal artery stenosis. A 45-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with complaints of headache, sweating, anxiety, dizziness, nausea, vomiting and severe hypertension. For the last several days, she was having a dull aching abdominal pain with a palpable, pulsatile, expansile and non-tender mass in the epigastric region. Hypertension was confirmed biochemically to result from excess catecholamine production. Abdominal computed tomography revealed the presence of a right adrenal pheochromocytoma. Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen demonstrated an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) of maximum transverse diameter of 4.5 cm with 3 cm lumen. Surgical removal of pheochromocytoma resulted in normalization of blood pressure to normal. Because of the asymptomatic 4.5 cm aneurysm, our patient was advised for periodic follow-up. To our belief, this is the first such case report emanating from India, citing this rare association between pheochromocytoma and AAA. It is concluded that when the two diseases occur simultaneously, both must be diagnosed accurately and treated adequately. Possible mechanisms of such an uncommon association are also discussed.

Keywords: Aortic aneurysm, Hypertension, Pheochromocytoma

Introduction

Pheochromocytoma is an uncommon cause of hypertension. It has an estimated prevalence of 0.1-1% in hypertensive patients.[1] It is a tumor of chromaffin cells and can be potentially lethal. The tumor secretes catecholamines and other substances,[2] either continuously or intermittently, giving rise to sustained or paroxysmal symptoms, respectively. Diagnosis is established by measuring the levels of catecholamines or their metabolites in the urine or blood; e.g., fractionated catecholamines, fractionated metanephrines, vanillyl mandelic acid (VMA) in 24-h urine specimen or plasma metanephrines.[3] Anatomic localization of the tumor is performed by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[4] Follow-up is essential because these tumors recur in some patients even after the removal of the primary tumor.[5]

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a localized dilatation (ballooning) of the abdominal aorta exceeding the normal diameter by more than 50%, and is the most common form of aortic aneurysm. They can be caused by smoking, atherosclerosis, infection, trauma, arteritis and cystic medial necrosis due to connective tissue disorders.[6] Treatment depends on the size of the lesion. Although previous reports of AAA in association with pheochromocytoma exist in the literature,[7,8,9] a similar coexistence has not been reported in Indian patients till date. We report the case of a patient who presented with mutual existence of these two conditions.

Case Report

A 45-year-old woman was admitted with complaints of headache, sweating, anxiety, dizziness, nausea and vomiting. She also had dull aching abdominal pain, which was poorly localized, non-radiating and not associated with any nausea, vomiting or altered bowel habits. She was a non-smoker with no significant family history. The patient was 168 cm tall and weighed 61 kg. On physical examination, there were no cafe au lait spots or neurofibromas. Her resting pulse rate was 100 beats/min. The patient's blood pressure was 230/140 mmHg without any asymmetry between the limbs. Abdominal examination revealed mild lower abdominal tenderness without any hepatomegaly and ascitis. There was a palpable, pulsatile, expansile and non-tender mass in the epigastric region. Rest of the systemic examination was unremarkable.

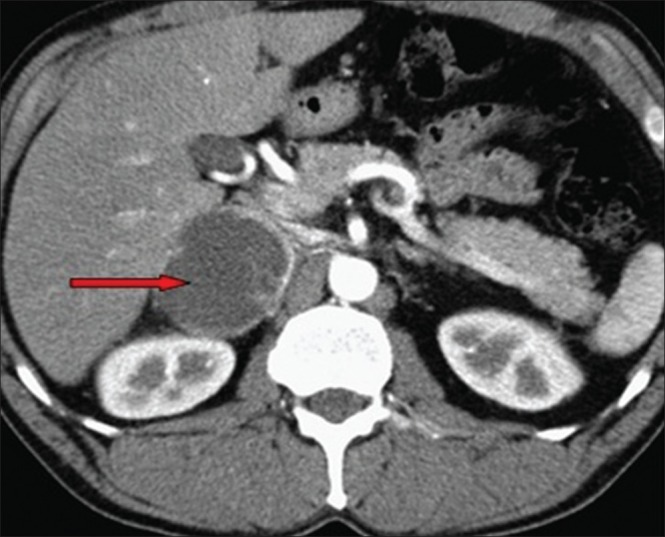

The patient's hemogram and blood biochemistry, including potassium, sodium, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase and creatinine levels, and liver function tests were normal. The electrocardiogram revealed left ventricular hypertrophy. No alterations in cardiac as well as renal function were observed. Thus, the presence of pheochromocytoma was suspected. The endocrinological evaluation was planned to measure the levels of catecholamines, steroids and the renin-angiotensin system parameters. The catecholamines and their metabolites were measured by performing high-performance liquid chromatography–electrochemical detection by using Biorad variant D 10. Automated enzyme immunoassay was used for the assessment of plasma cortisol. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), plasma renin activity and plasma aldosterone were estimated by radioimmunoassay methods by using the Roche E 601 analyzer. This battery of tests revealed increase in plasma metanephrines, 24-h fractionated metanephrines and VMA and supine plasma renin activity, and that plasma aldosterone concentrations were increased [Table 1]. Plasma cortisol and hormone ACTH levels were within normal ranges [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline biochemical parameters of the patient

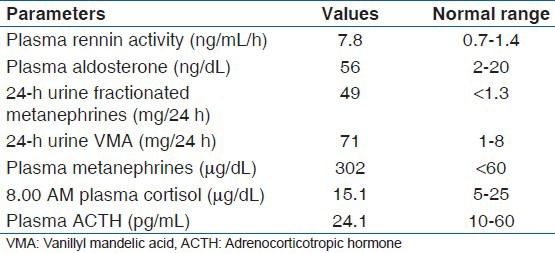

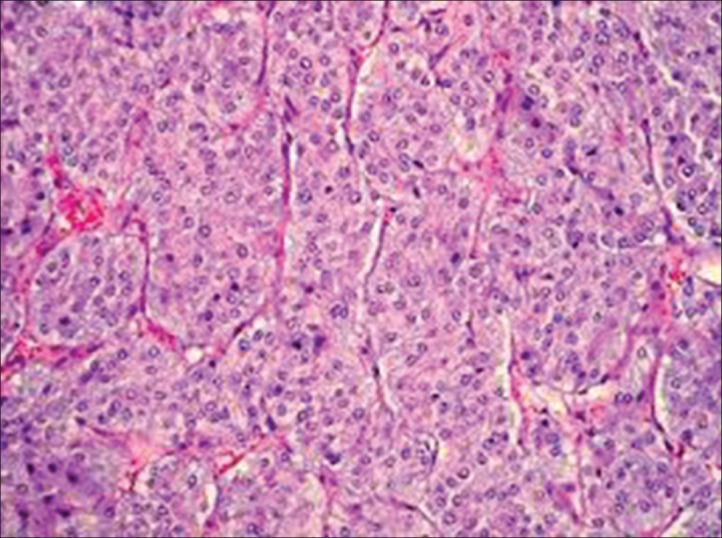

Abdominal CT revealed a large, well-defined, heterogenous para-aortic mass (6 cm × 3 cm) with attenuation score of 35 hounsfield units (HU) at the upper pole of the right kidney without any calcification [Figure 1]. Further work up to establish the etiology of the abdominal pain included MRI of the abdomen, which demonstrated a 4.5 cm AAA with 3 cm lumen [Figure 2]. A diagnosis of right pheochromocytoma was made, and surgical treatment was recommended to her. Alfa receptor blocking therapy with prazosin was instituted, followed by β-blocker after adequate α-blockade. After 2 weeks, hypertension was well controlled and the remaining symptomatology disappeared. With adequate blood pressure control, laparoscopic adrenalectomy was performed on the patient. Light microscopy of the specimen showed characteristic organoid or zellballen nest of cells, confirming the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma, with no cytoplasmic inclusion, pleomorphism, cytological alterations or necrosis; the mitotic index was low [Figure 3]. Because of the asymptomatic 4.5 cm aneurysm, our patient was advised for periodic follow-up of the lesion.

Figure 1.

Abdominal computed tomography revealing a large, well-defined, heterogenous para-aortic mass (6 cm × 3 cm) with attenuation score of 35 hounsfield units at the upper pole of the right kidney without any calcification (red arrow)

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen depicting a 4.5 cm abdominal aortic aneurysm with 3 cm lumen

Figure 3.

Histology of the biopsied specimen revealing characteristic organoid or zellballen nest of cells

During the post-operative period, the blood pressure was normal and the patient's convalescence was uncomplicated. She was discharged on the 7th post-operative day. During the next 12 months, the patient's blood pressure remained normal and the size of the aneurysm did not change. A 24-h urine sample was collected for analyzing the levels of metanephrines and VMA, which were found to be within the normal ranges. At present, the patient is asymptomatic and requires no medications.

Discussion

Pheochromocytoma lesions have been described in the past in association with several vascular anomalies including renal artery stenosis, inferior vena cava thrombosis, nonspecific aortoarteritis etc.[7,8,9,10] Two aspects make our report unusual: (i) the coexistence of pheochromocytoma with AAA in the patient and (ii) although there are case reports citing the association between pheochromocytoma and AAA,[11,12,13] to our sincere belief, this is the first such report citing this uncommon association from India.

AAAs occur more frequently in males than in females, and the incidence increases with age. AAAs ≥4.0 cm may affect 1-2% of men older than 50 years. At least 90% of all AAAs >4.0 cm are related to atherosclerotic disease, and most of these aneurysms are below the level of the renal arteries. Most of them are asymptomatic, detected on routine clinical examination or abdominal radiography, which may pick up the calcified outline of the aneurysm. Some may complain of strong pulsating sensations. Prognosis is related to both the size of the aneurysm and the severity of the coexisting coronary artery, and cerebrovascular disease. The risk of rupture increases with the size of the aneurysm: The 5-year risk for aneurysms <5 cm is 1-2%, whereas it is 20-40% for aneurysms >5 cm in diameter. The formation of mural thrombi within aneurysms may predispose to peripheral embolization.[14]

Although cases of renal artery stenosis and renal artery aneurysm have been described,[15] we found an uncommon association with AAA in our Indian patient. Possible etiological factors leading to the coexistence of aortic aneurysm with pheochromocytoma are: (i) persistent exposure to high catecholamines leads to damage and subsequent weakening of vascular wall, (ii) associated cigarette smoking, increasing age, hypertension and atherosclerosis, (iii) coexistence of vasculitis like Takayasu's disease, Giant cell arteritis and cystic medial necrosis due to Marfan syndrome and Ehlers Danlos Syndrome and (iv) chance association. The hyperreninemic hyperaldosteronism in our patient could be attributed to the coexisting uncontrolled hypertension.

Management of patients with coexisting pheochromocytoma and AAA needs operative resection of the adrenal mass observational/interventional management of aneurysm. The goals of the operation include (i) removal of the tumor with post-operative normotension and (ii) repair of aortic aneurysm, because the site of aneurysm serves as a site for potential thrombus formation. Minimally invasive techniques are being increasingly used for resection of adrenal tumors and to treat renal artery lesions. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy is performed by either the transperitoneal or retroperitoneal approach.[16] Our patient was subjected to laparoscopic adrenalectomy after adequate pre-operative blood pressure control by α-blockers, followed by β-blockers. For abdominal aneurysms, the current treatment guidelines for AAAs suggest elective surgical repair when the diameter of the aneurysm is greater than 5 cm. However, recent data suggest medical management for AAAs with a diameter of less than 5.5 cm.[17] Although a possibility of rupture of 4.5 cm AAA is low, rupture can occur even in small AAAs, the risk pegged at 0.5-5.0%.[18] The risk of rupture of AAAs is increased in women compared with men. In some studies, the rate of rupture of aneurysms that were 4.0-5.5 cm in diameter was four times higher in women compared with men, and the rate of rupture of aneurysms ≥5 cm was significantly higher in women.[19] As per the 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with peripheral artery disease, endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is recommended in patients who are good surgical candidates and can be followed-up after the operation.[20]

In candidates planned for surgical management of aneurysm EVAR, pre-operative cardiac and general medical evaluations are essential. Pre-existing coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, pulmonary disease, advanced age and diabetes add to the surgical risk. Beta-adrenergic blockers decrease the perioperative cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. EVAR with stent placement is an emerging approach, with approximately 40% mortality. After acute rupture, the emergent operation is associated with a 40-50% mortality.[14] But, the mortality results vary. In a study by Brewster, et al., it was seen that over a period of 12 years of follow-up, all-cause mortality occurred in 28.2% patients, of which 11% of the cases were attributable to the aneurysm or its treatment.[21] Because of the asymptomatic 4.5 cm aneurysm, our patient was advised for periodic follow-up. Given the risk of rupture even in small AAAs, higher risk of rupture in women, harmful effects of coexisting pheochromocytoma and the relatively younger age of the patient make her a possible candidate for EVAR. We are planning to explore this option during her subsequent follow-up visit.

Conclusion

Pheochromocytoma is known to be associated with vascular abnormalities. Although cases of renal artery stenosis and renal artery aneurysm have been described previously,[12] we found an uncommon phenomenon of pheochromocytoma associated with AAA. The aneurysm may represent a form of catecholamine-induced vasculitis or weakening of the vascular wall. Our article calls for more research to confirm or refute the proposed hypothetical association.

Acknowledgment

All the authors extend their heartfelt thanks to Dr Jagadeesh Tangudu, MTech, MS, PhD, and Mrs Sowmya Jammula, MTech, for their immense and selfless contribution toward manuscript preparation, language editing and final approval of the text.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Mannelli M, Ianni L, Cilotti A, Conti A. Pheochromocytoma in Italy: A multicentric retrospective study. Eur J Endocrinol. 1999;141:619–24. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1410619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasaki A, Yumita S, Kimura S, Miura Y, Yoshinaga K. Immunoreactive corticotropin-releasing hormone, growth hormone releasing hormone, somatostatin, and peptide histidine methionine are present in adrenal pheochromocytomas, but not in extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70:996–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-4-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenders JW, Pacak K, Walther MM, Linehan WM, Mannelli M, Friberg P, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: Which test is best? JAMA. 2002;287:1427–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szolar DH, Korobkin M, Reittner P, Berghold A, Bauernhofer T, Trummer H, et al. Adrenocortical carcinomas and adrenal pheochromocytomas: Mass and enhancement loss evaluation at delayed contrast-enhanced CT. Radiology. 2005;234:479–85. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2342031876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plouin PF, Chatellier G, Fofol I, Corvol P. Tumor recurrence and hypertension persistence after successful pheochromocytoma operation. Hypertension. 1997;29:1133–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.5.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: A best-evidence systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:203–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-3-200502010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kota SK, Kota SK, Meher LK, Jammula S, Tripathy PR, Panda S, Modi KD. Coexistence of pheochromocytoma with uncommon vascular lesions. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:962–71. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.103000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kota SK, Kota SK, Meher LK, Tripathy PR, Sruti J, Modi KD. Pheochromocytoma with renal artery stenosis: A case-based review of literature. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2012;3:36–9. doi: 10.4103/0975-3583.91601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar Kota S, Krishna Kota S, Tripathy PR, Jammula S, Kumar Meher L, Modi KD. Pheochromocytoma with Nonspecific Aortoarteritis: an Unusual Association. Int J Endcrinol Metab. 2011;9:416–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kota SK, Kota SK, Meher LK, Jammula S, Modi KD. Pheochromocytoma with Inferior Vena Cava thrombosis: An unusual association. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2012;3:160–4. doi: 10.4103/0975-3583.95375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson JF, Clifford PC, McEwan JA, Chant AD. Phaeochromocytoma and abdominal aneurysm: Confirmation of diagnosis after aortic surgery using mIBG imaging. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1989;3:457–9. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(89)80056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehata T, Karasawa F, Watanabe K, Satoh T. Unsuspected pheochromocytoma with abdominal aortic aneurysm: A case report. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 1999;37:27–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spanos C, Moros I, Spanos G, Drakotou I, Mavromanolis H, Spanos P. Elective resection of pheochromocytoma with concomitant abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2006;36:741–3. doi: 10.1007/s00595-005-3233-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creager MA, Loscalzo J. Diseases of Aorta. In: Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Longo DL, Braunwald E, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. pp. 1563–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill IS, Meraney AM, Bravo EL, Novick AC. Pheochromocytoma coexisting with renal artery lesions. J Urol. 2000;164:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Pizzo JJ, Schiff JD, Vaughan ED. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Curr Urol Rep. 2005;6:78–85. doi: 10.1007/s11934-005-0071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortality results for randomised controlled trial of early elective surgery or ultrasonographic surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Lancet. 1998;352:1649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brewster DC, Cronenwett JL, Hallett JW, Jr, Johnston KW, Krupski WC, Matsumura JS. Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Report of a subcommittee of the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:1106–17. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norman PE, Powell JT. Abdominal Aortic Aneurys. The Prognosis in Women Is Worse Than in Men. Circulation. 2007;115:2865–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.671859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Interventional Radiology; Society for Vascular Medicine; Society for Vascular Surgery. Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, Sidawy AN, Beckman JA, Findeiss LK, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with peripheral artery disease (updating the 2005 guideline) Vasc Med. 2011;16:452–76. doi: 10.1177/1358863X11424312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brewster DC, Jones JE, Chung TK, Lamuraglia GM, Kwolek CJ, Watkins MT, et al. Long-term outcomes after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: The first decade. Ann Surg. 2006;244:426–38. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000234893.88045.dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]