Abstract

The merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP-1) is a blood stage antigen currently being tested as a vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Determining the MSP-119 haplotype(s) present during infection is essential for assessments of MSP-1 vaccine efficacy and studies of protective immunity in human populations. The C-terminal fragment (MSP-119) has four predominant haplotypes based on point mutations resulting in non-synonymous amino acid changes: E-TSR (PNG-MAD20 type), E-KNG (Uganda-PA type), Q-KNG (Wellcome type), and Q-TSR (Indo type). Current techniques using direct DNA sequencing are laborious and expensive. We present an MSP-119 allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR)/ligase detection reaction–fluorescent microsphere assay (LDR-FMA) that allows simultaneous detection of the four predominant MSP-119 haplotypes with a sensitivity and specificity comparable with other molecular methods and a semi-quantitative determination of haplotype contribution in mixed infections. Application of this method is an inexpensive, accurate, and high-throughput alternative to distinguish the predominant MSP-119 haplotypes in epidemiologic studies.

INTRODUCTION

Merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP-1) is the most abundant protein found on the surface of blood stage Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) merozoites and is currently being tested as a vaccine against Pf malaria. MSP-1 is expressed late in the blood stage cycle as a ~200-kd precursor protein attached to the merozoite surface through a C-terminal glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. Full-length MSP-1 undergoes primary proteolytic processing just before schizont rupture to produce a complex of four MSP-1 fragments that remain non-covalently associated on the merozoite surface.1 During merozoite invasion of the erythrocyte, the MSP-142 fragment that anchors the complex to the merozoite surface is further processed to produce MSP-133 and MSP-1191–3. MSP-119 remains on the merozoite surface during invasion and is readily detectable in the newly infected erythrocytes.2 The MSP-1 gene can be divided into conserved, semi-conserved, and variable blocks based on comparisons of deduced amino acid sequences of various clones and field isolates.4 Block 17 encodes MSP-119 that includes 98 highly conserved amino acids with the exception of residues 1644, 1691, 1700, and 1701. Non-synonymous changes at these positions result in four predominant haplotypes: E-TSR (PNG-MAD20 type), E-KNG (Uganda-PA type), Q-KNG (Wellcome type), and Q-TSR (Indo type).5–8

Antibodies directed against the conserved MSP-119–kDa C-terminal region are associated with protection against malaria infection or disease.9–12 It is unclear whether protective immune responses are haplotype specific or if past exposure to one haplotype conveys cross protection to another. Some cross-protection has been shown in animal models13 but not definitively in human studies. MSP-1 vaccines are currently in clinical trials. To interpret immunologic endpoints for MSP-1 vaccines tested in malaria-endemic areas, it is important to determine the MSP-119 haplotype variants within a population and their influence on the development of MSP-119–specific immunity. Traditionally, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and DNA sequencing have been preferred methodologies to determine allelic prevalence in a population. This method has been used to estimate the proportions of alleles in mixed Pf infections when those differences were caused by single nucleotide polymorphisms; however, this method tends to be costly, does not lend itself to high-throughput sample processing, and requires knowledge of bioinformatics for accurate comparisons within large datasets.14 Cloning multiple PCR amplicons from a single individual can also be used to determine the proportion of alleles in a mixed infection, but this is impractical on a large scale with population-based studies. New methods that exploit targeted sequencing of specific genes can overcome laborious cloning.15 These methods are very precise, but expensive and time consuming. Real-time quantitative PCR (RTQ-PCR) has been used to determine Plasmodium parasite density but amplifies a species-specific ribosomal subunit16,17 and is not successful at distinguishing allelic variants that differ by single nucleotide polymorphisms. Additionally, it is limited to only a few allelic markers that can be differentiated in a single multiplexed reaction.

Our goal was to develop a high-throughput, accurate, and inexpensive method to determine the relative contribution of each predominant MSP-119 haplotype within a mixed Pf strain infection. We adapted a PCR-based ligase detection reaction–fluorescent microsphere assay (LDR-FMA) method to distinguish between the four predominant MSP-119 haplotypes, their relative frequency within a population, and their quantitative contribution to an individual sample within a mixed infection. This method is particularly suited to monitor Pf MSP-1 genetic diversity within and between human populations and will significantly contribute to understanding MSP-1 vaccine intervention outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Healthy individuals (101 adults and 100 children) from the malaria holoendemic sub-location of Kanyawegi, Kenya, were enrolled in July 2003 during a time of relatively high malaria transmission. Adults were older than 18 years of age, and the average age of the children was 7.7 years old. All study participants were afebrile and had normal age-adjusted hemoglobin levels. Ethical approval for human study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Case Western Reserve University, University Hospital of Cleveland, and the Ethical Review Committee at the Kenya Medical Research Institute. Adults participating in this study signed a written consent form in English or Duhluo (the local language), and parents or guardians signed in the case of minors.

Blood smear examination

Thick and thin blood smears (BSs) were prepared, fixed in 100% methanol, stained with 5% Giemsa solution, and examined by light microscopy for P. falciparum–infected erythrocytes. The density of parasitemia was expressed as the number of asexual P. falciparum per microliter of blood assuming a leukocyte count of 8,000/μL.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from 200 μL of venous blood (collected in EDTA anti-coagulant) and parasite cultures (3D7 and K1 strains) using QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

RTQ-PCR

Extracted DNA (2.5 μL) was used as template for amplification of the multicopy P. falciparum 18S small subunit ribosomal (ssu) RNA gene by RTQ-PCR.17,18 Results are reported as copies per microliter of blood.

MSP-119 DNA sequencing

Samples were sequenced from MSP-119 PCR products using primers and conditions previously described.8 PCR products were purified using QIAquick 96 PCR purification kit (Qiagen). DNA sequencing was performed by MGW Biotech (MGW Biotech, High Point, NC).

MSP-119 and Pf rRNA PCR amplification

PCR primers were synthesized8 to amplify a 376-bp region of MSP-119 containing the point mutations of interest: upstream primer 5′AACATTTCACAACACCAATGC-3′ and downstream primer 5′TTAAGGTAACATATTTTAACTCCTAC-3′ (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). This set of MSP-119 PCR primers was multiplexed with Pf-specific PCR primers for ssu rRNA gene fragment as previously published.19 Each PCR (25 μL) contained 1× PCR buffer (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT), 1.5 mmol/L MgCl, 200 μmol/L dNTPs, 300 nmol/L of each primer, and 1.5 units of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), to which 1 μL sample DNA was added. Cycling conditions were as follows: 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 63°C for 2 minutes for 35 cycles, followed by a final extension at 63°C for 7 minutes. A 3-μL aliquot was removed from each reaction at 27 cycles during optimal non-saturated PCR cycling. Twenty-seven-cycle PCR aliquots were used for the semi-quantitative determination of MSP-119 allele and Pf infection levels. 19LDR-FMA using 35-cycle PCR products were used to determine the presence of MSP-119 alleles and detect Pf infection in samples. PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels, stained with SYBR Gold (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and visualized on a Storm 860 using ImageQuant, 5.2 software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

LDR-FMA

The LDR-FMA was adapted to distinguish between single nucleotide polymorphisms that recognize G versus A corresponding to amino acid position 1644 (E versus Q variant), and GCA versus ACG (position 1699–1701) corresponding to the last two nucleotide bases of S and N codons and the first base of the R and G codons, respectively.8 Four allele-specific probes and two fluorescently labeled conserved sequence probes were designed (Table 1). Additionally, a Plasmodium-specific fluorescently labeled conserved probe (designated “Common1”) and a Pf specific probe (designated “Pf1”) previously described were included in the LDR-FMA reaction.19 In total, five specific probes (four MSP-119–allele specific and one Pf-specific) and three conserved sequence probes were included in the multiplexed detection reaction. To one LDR reaction, 1 μL of the PCR reaction was added (either from the 27-cycle or 35-cycle PCR product aliquot). The LDR reaction was performed with 1 μL of the PCR reaction, 10 nmol/L (200 fmol) of each probe, and 2 units of Taq DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) in a buffer containing 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.6, 25 mmol/L potassium acetate, 10 mmol/L magnesium acetate, 1 mmol/L NAD+, 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol, and 0.1% Triton X-100. LDR reactions (total volume 15 μL) were heated to 95°C for 1 minute, followed by 32 thermal cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds and 58°C for 2 minutes. Five microliters of the multiplexed LDR reaction was added to 60 μL of hybridization solution: 3 mol/L tetramethylammonium chloride (TMAC), 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 3 mmol/L EDTA, pH 8.0, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, containing 250 Luminex FlexMAP microspheres from each allelic set (total number = 5). The hybridization reactions were heated to 95°C for 90 seconds and incubated at 37°C for 40 minutes to allow hybridization between allele-specific LDR products and microsphere-labeled anti-TAG probes. After hybridization, 6 μL of streptavidin-R-phycoerythrin (Molecular Probes) in TMAC hybridization solution (20 ng/μL) was added to the hybridization reaction and incubated at 37°C for 40 minutes in Costar-6511M polycarbonate 96-well V-bottom plates (Corning, Corning, NY).19,20 Detection of allele-specific LDR:microsphere-labeled anti-TAG hybrid complexes was performed using a BioPlex array reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).19 Each Luminex fluorescent microsphere emits a unique fluorescent “classification” signal across the range of 658–712 nm. “Reporter” fluorescent signals from R-phycoerythrin are detected, classified into the allele-specific bins, and reported as median fluorescent intensity (MFI) by the BioPlex array reader and BioPlex Manager 3.0 software.

Table 1.

LDR primers for differentiation of MSP-119 haplotypes

| Primer sequence | FlexMAP microsphere name | |

|---|---|---|

| Allele-specific primers | ||

| MSP-119-E | 5′-ctaactaacaataatctaactaacAATGCGTAAAAAAACAATGTCCAG-3′ | 80 |

| MSP-119-Q | 5′-aatcctacaaatccaataatctcatAATGCGTAAAAAAACAATGTCCAC-3′ | 60 |

| MSP-119-TSR | 5′-ctacaaacaaacaaacattatcaaCGAAGAAGATTCAGGTAGCAGCA-3′ | 28 |

| MSP-119-KNG | 5′-tcaaaatctcaaatactcaaatcaCGAAGAAGATTCAGGTAGCAACG-3′ | 18 |

| Conserved primers | ||

| MSP-119-Common1 | 5′-Phos-AAAATTCTGGATGTTTCAGACATT-3′-Biotin | |

| MSP-119-Common2 | 5′-Phos-GAAAGAAAATCACATGTGAATGTA-3′-Biotin | |

Nucleotides in lowercase represent the TAG sequences added to the 5′ end of each allele-specific LDR primer. Nucleotides in bold represent differences between the differentiated alleles (Q vs. E and KNG vs. TSR).

RESULTS

MSP-119 PCR/LDR-FMA determined allele specificity

MSP-119–allele specific determination was conducted using PCR products generated after 35 PCR cycles when saturated cycling occurs. Each Luminex fluorescent microsphere has 105–106 anti-TAG oligos per bead. Thus, the maximal fluorescent signal associated with each microsphere must be ascertained. Determining positive threshold cut-off values was established for each allele-specific microsphere using DNA isolated from cultured Pf strains 3D7 (E-TSR haplotype) and K1 (Q-KNG haplotype). Parasite DNA was combined in a 1:1 ratio and serially diluted. Figure 1 shows the average MFIs for each allele at each dilution for 16 separate MSP-119 PCR/LDR-MFA experiments to determine each microsphere threshold value.20 Fluorescence cut-off values for micro-spheres associated with “Q” and “E” were set at an MFI of 800, and cut-off values for microspheres associated with “KNG” and “TSR” were set at an MFI of 3,000. The cut-off values for the microsphere associated with “Pf” was set at an MFI of 3,000. Thresholds for MSP-119 allele or Pf detection did not change when experiments were performed with background human DNA added to cultured parasite DNA (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Allele-specific microsphere MFI averaged from 16 separate MSP-119 PCR/LDR-MFA experiments. Controls include ETSR only, QTSR only, and water. ETSR only represents MSP-119 PCR/LDR-MFA performed with DNA from 3D7 parasites. QKNG only represents MSP-119 PCR/LDR-MFA performed with DNA from K1 parasites. A 1:1 combination of 3D7 and K1 parasite DNA was serially diluted from 1:10 to 1:10,000. The positive threshold for Q- and E-associated microspheres was set at 800 MFI (dashed horizontal line) and 3,000 MFI for KNG and TSR (solid horizontal line). The positive threshold for Pf specific associated microsphere was set at 3,000 MFI. Determination of positive alleles was made using 35-cycle PCR products.

Sensitivity and specificity of MSP-119 allele-specific PCR/LDR-FMA compared with sequencing

Sixty-one Pf PCR-positive (56 BS positive) Kenyan samples were sequenced using traditional direct sequencing and compared with PCR/LDR-FMA. In a single sample, multiple alleles may be present; each sample has the potential to have all four alleles present. Therefore, 244 alleles (61 × 4) had to be determined. Each allele (Q, E, KNG, and TSR) was therefore assessed independently for each sample. As an example, sequencing a single sample may detect alleles Q and KNG. Q and KNG would be considered “positive” alleles, whereas E and TSR would be considered “negative” alleles for this sample. We found 158 alleles that were positive both by LDR-FMA and direct sequencing methods (true positives); 59 alleles were negative both by LDR-FMA and direct sequencing (true negatives); 3 alleles were positive by LDR but negative by direct sequencing (false positives); and 24 alleles were negative by LDR but positive by direct sequencing (false negatives). Compared with traditional DNA sequencing, the gold standard, MSP-119 PCR/LDR-FMA had a sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 95%. Specificity was most affected by the E allele, and sensitivity was most affected by the TSR allele. Repeat PCR/LDR-FMA experiments showed 99% concordance, indicating excellent reproducibility.

Pf parasite density by BS, RTQ-PCR, and PCR/LDR-FMA

Kenyan samples (N = 201) were analyzed by microscopy, RTQ-PCR and Pf-specific PCR/LDR-FMA (27 cycles) to compare parasite densities. As expected in a malaria ho-loendemic area, more children (82%) than adults (34%) were Pf positive by BS, with parasite densities of 3,740/μL blood (range, 80–48,000) and 148/μL blood (range, 80–5,120), respectively. We found 117 of the 201 (58%) samples were positive by BS. Parasite density as determined by the three methods showed a positive correlation between increasing Pf-specific MFI and increasing Pf parasite detection (by BS or RTQ-PCR; data not shown), which is consistent with previously published studies.19 As with most nucleic acid detection methods, PCR-based LDR-FMA is more sensitive than microscopy for Pf infection detection. Of 84 BS-negative Kenyan samples, 24 were positive by Pf LDR-FMA (35 PCR cycles and MFI cut-off of 3,000) and 37 were positive by Pf RTQ-PCR (copy number > 10,000). Nineteen of the BS negative samples were positive by both Pf LDR-FMA and Pf RTQ-PCR methods.

Relative MSP-119 allele contribution to Pf infection can be determined with MSP-119 PCR/LDR-FMA

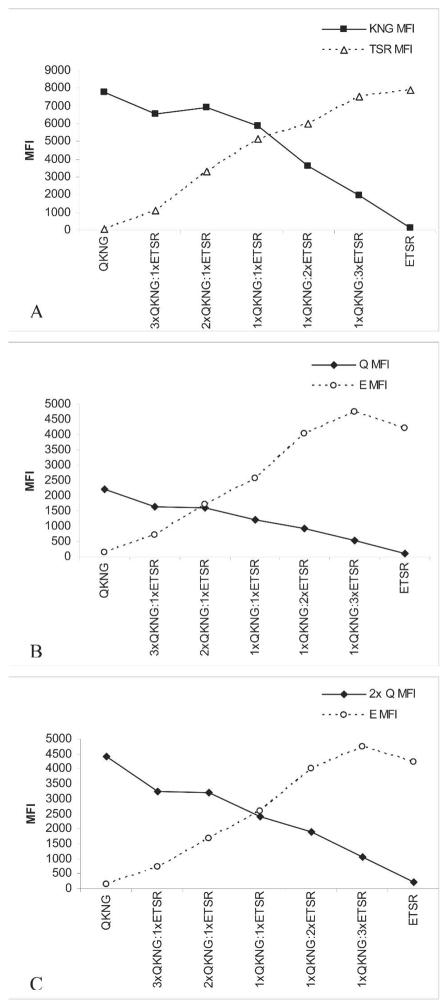

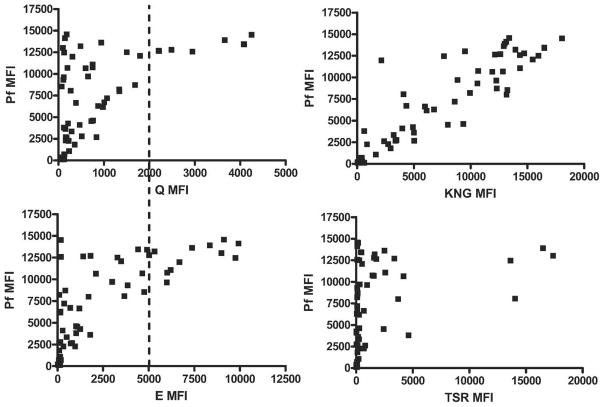

The MSP-119 allele-specific PCR/LDR-FMA was multiplexed with the Pf specific PCR/LDR-FMA method so that semi-quantitative Pf infection levels and relative MSP-119 allele contributions to haplotypes could be determined. Optimal non-saturated PCR cycling for determining semi-quantitative Pf infection levels was previously found to be 27 cycles.19 To establish that allele-specific MFIs reflect quantitative differences in their contribution to a mixed strain Pf infections, known amounts of cultured parasite DNA from strains 3D7 (E-TSR) and K1 (Q-KNG) were combined at various concentrations (i.e., 3xQ-KNG:1xE-TSR, 2xQ-KNG:1xE-TSR, 1xQ-KNG:1xE-TSR).20 Twenty-seven cycles of MSP-119–specific PCR/LDR-FMA were performed, with the results summarized in Figure 2. Figure 2A compares KNG to TSR microspheres with similar maximum MFIs and shows the expected increase or decrease according to the relative amounts of each allele. Figure 2B shows Q versus E microspheres that do not have similar MFI ranges, and therefore the relative contribution from the less intense microsphere (Q) appears skewed to the left. However, if the MFI for Q is adjusted by a factor of 2, the expected result occurs, and the relative Q:E contributions can be discerned (Figure 2C). Thus, the predominant allele can be determined by a stronger relative fluorescence signal in each mixture. Using Kenyan samples, comparisons of each allele-specific MFI can be made against Pf-specific semi-quantitative results. Thus, different FlexMap microsphere intensities can be compared directly to each other (Figure 3). Using this method, KNG- and TSR-associated microspheres had comparable fluorescence intensity ranges. Q and E microspheres did not. E MFIs were approximately twice as intense as Q MFIs. This is consistent with mixed cultured parasite DNA experiments. Figure 3 also shows positive correlations between allele intensity and Pf MFI, further validating the semi-quantitative aspect of this method. There was little variability of allele-specific MFI observed in repeated experiments (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Relative allele contribution. Known amounts of cultured parasite DNA from strains 3D7 (ETSR) and K1 (QKNG) were combined at various concentrations (i.e., 3xQKNG:1xETSR, 2xQKNG:1xETSR, 1xQKNG:1xETSR) and measured at 27 cycles of MSP-119–specific PCR/LDR-FMA. A, MFIs of KNG and TSR mi-crospheres increase or decrease in direct relation to the relative amount of each haplotype. B, MFIs of Q and E microspheres do not increase or decrease in direct relation to the relative amount of each haplotype in the experimental sample. C, However, if the Q MFI is doubled, the expected result occurs and the relative Q:E contributions can be more directly discerned.

Figure 3.

Relative MFI of comparative Luminex microspheres for each allele tested using Kenyan samples. An arbitrary dashed line was drawn intersecting the Q and E allele MFI axes showing the relative differences in MFI for each microsphere: a “Q” MFI of 2,000 was equivalent to an “E” MFI of 5,000. Using this comparative scale, the relative contribution of each allele to the Pf infection was determined. In contrast, the KNG- and TSR-associated microspheres had a similar MFI range, and therefore direct comparisons of relative intensity could be made. A positive correlation between allele MFI and Pf MFI can be observed.

Using qualitative and quantitative MSP-119 allele determination, haplotype assignments were made for each Pf-positive sample. An example of how haplotype assignments were determined using 35 and 27 PCR cycle products with LDR-FMA in field samples is shown in Table 2. Twenty-seven-cycle Q allele MFIs were adjusted as described in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Example of haplotype assignment using PCR products from both 27- and 35-cycle reactions with LDR-FMA allele detection

| Sample | 35-cycle MFI

|

Positive alleles | 27-cycle MFI

|

Major haplotypes | Minor haplotypes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | E | KNG | TSR | 2xQ | E | KNG | TSR | ||||

| A | 6301 | 6541 | 2367 | 688 | Q/E KNG | 4652 | 2074 | 16436 | 524 | QKNG | EKNG |

| B | 6228 | 16785 | 25018 | 935 | Q/E KNG | 4834 | 6051 | 17375 | 508 | QKNG/EKNG | |

| C | 5680 | 3916 | 19060 | 3237 | Q/E KNG/TSR | 4444 | 1424 | 12162 | 1802 | QKNG | ETSR |

Thirty-five-cycle MFI in bold indicates positive alleles. Major vs. minor allelic contributions to haplotype assignments were determined using 27-cycle MFI. An adjusted 27-cycle Q allele MFI (designated 2xQ) as described in Figure 2 and Results was used. In sample A, Q, E, and KNG alleles are positive (35 cycles). The Q allele contribution to infection is greater than the E allele contribution, thus determining the haplotype assignment of QKNG > EKNG. Conversely, in sample B, a predominant haplotype cannot be inferred as the 27-cycle comparative MFIs because Q and E are too similar. In sample C, all four alleles are positive. Assuming a two-strain infection, Q and KNG alleles have the highest MFI and are therefore assigned as the major haplotype. E and TSR have lesser MFI and are assigned as the minor haplotype.

Prevalence and intensity of MSP-119 haplotypes in field isolates

We used MSP-119–allele specific PCR/LDR-FMA to evaluate field isolates and found 28% (17) of the samples to have single haplotype infection, 62% (38) with mixed infections, and 10% (6) were negative. Single infections contained only E-KNG or Q-KNG haplotypes. In mixed infections where two or three alleles were detected, the more prevalent haplotypes were E-KNG (31) and Q-KNG (30), with E-TSR (5) and Q-TSR (1) being less common as a co-infecting variant. Thirteen samples were positive for all four alleles; therefore, in these samples, dominant haplotype assignments were made within each infection using semi-quantitative data based on the 27 PCR cycle LDR-FMA results with the assumption that only two Pf strains infected an individual at the sampling time point. Of these 13 samples, haplotype assignment of Q-KNG and E-TSR was made in 8 samples, and E-KNG and Q-TSR was made in 5 samples. Using this criterion for assigning major haplotype within samples with four alleles, the overall haplotype prevalence in this study population was Q-KNG (38), E-KNG (36), E-TSR (13), and Q-TSR (6).

Of the 38 samples where three or four alleles were detected, 25 had a clear predominant (major) haplotype and a subordinant (minor) haplotype when comparing microsphere intensities after adjusting for the Q allele microsphere with the lower MFI (Figure 2C). In the mixed infection samples, the predominant haplotypes were Q-KNG and E-KNG. Q-TSR was always a minor component of an infection and was not detected as a single infecting haplotype.

DISCUSSION

MSP-119 allele–specific PCR/LDR-FMA is an inexpensive, accurate, and high-throughput method well suited for monitoring MSP-119 haplotypes in immunoepidemiologic studies or MSP-1 vaccine efficacy trials. With its excellent sensitivity and specificity and at 1/10th the cost compared with traditional DNA sequencing, the MSP-119 PCR/LDR-FMA is a feasible option for large population-based studies. The unique feature of this method is that within one multiplexed reaction, semi-quantitative Pf infection levels and relative MSP-119 haplotype contributions can be determined. Establishing the relative contribution of each MSP-119 haplotype will allow a more complete understanding of MSP-119 variability, which may be especially relevant for determining vaccine efficacy and immunologic cross-reactivity studies. Another advantage of this technique is that it can be expanded to include other rare MSP-119 haplotypes or other SNPs in genes of interest. One hundred unique fluorescent microspheres are available that potentially can be multiplexed in a single-tube reaction. Recently, examination of 22 different SNPs from three malaria drug resistance genes was multiplexed into one LDR-FMA reaction.20 This method lends itself to further expansions to include unique sequences from any Plasmodium, human, or other species gene of interest that then can be compared directly.

The concentration of template DNA for amplification or sequencing has been shown to not affect the determination of the relative proportion of alleles in mixed infections.14 For the LDR method, we start with a uniform amount of DNA extracted from whole blood with varying concentrations of Plasmodium genomic DNA determined by the parasite infection density. We found no differences in our MFI threshold determinations at different levels of parasitemia.

MSP-119 haplotypes have traditionally been discovered using direct DNA sequencing techniques that have been adapted to estimate proportions of alleles within an infection using proportional sequencing.14 The advantage of direct sequencing over the PCR/LDR-FMA method is its ability to detect rare or novel haplotypes. Recently, a novel pyrose-quencing method has been shown to be able to identify rare haplotypes in blood samples from Mali.15 This MSP-119 method can also determine the relative haplotype contribution to infection but does not indicate overall Pf infection levels and is more labor intensive than the MPS-119 PCR/LDR-FMA method.

Our results show that the E-KNG and Q-KNG haplotypes are most common in our study population. Prior studies from nearby regions show similar results21 demonstrating MSP-119 haplotype stability despite its immunologic recognition. MSP-142 vaccine trials ongoing in this region use the MSP-142 3D7 (E-TSR) variant.22 It is unclear whether immunity is haplotype specific underscoring the need to investigate parasite genetics in conjunction with vaccine and immunologic studies. The haplotype-specific PCR/LDR-FMA technique is ideal for such studies.

Additionally, the MSP-119 PCR/LDR-FMA assay is more sensitive than BS for detecting Pf infection. To understand the kinetics of infection, immunologic pressures on haplotype frequency and individual susceptibility to clinical disease, accurate detection and quantification of infection must be understood. High-throughput methods are essential for large population-based studies of malaria needed to understand these complex interactions.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was published with permission of the Director of the Kenya Medical Research Institute. We thank the study participants and Kenyan field and laboratory technicians.

Financial support: This research was funded by NIH R01 AI43906 (JK), K08 AI51565 (AM), and T32 AI0702427 (AD).

References

- 1.Blackman MJ. Proteases involved in erythrocyte invasion by the malaria parasite: function and potential as chemotherapeutic targets. Curr Drug Targets. 2000;1:59–83. doi: 10.2174/1389450003349461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holder AA, Blackman MJ, Burghaus PA, Chappel JA, Ling IT, McCallum-Deighton N, Shai S. A malaria merozoite surface protein (MSP1)-structure, processing and function. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87(Suppl 3):37–42. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761992000700004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell SA, Well I, Fleck SL, Kettleborough C, Collins CR, Blackman MJ. A single malaria merozoite serine protease mediates shedding of multiple surface proteins by juxtamembrane cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23890–23898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Udhayakumar V, Anyona D, Kariuki S, Shi YP, Bloland PB, Branch OH, Weiss W, Nahlen BL, Kaslow DC, Lal AA. Identification of T and B cell epitopes recognized by humans in the C-terminal 42-kDa domain of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein (MSP)-1. J Immunol. 1995;154:6022–6030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conway DJ, Fanello C, Lloyd JM, Al-Joubori BM, Baloch AH, Somanath SD, Roper C, Oduola AM, Mulder B, Povoa MM, Singh B, Thomas AW. Origin of Plasmodium falciparum malaria is traced by mitochondrial DNA. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;111:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee EA, Flanagan KL, Odhiambo K, Reece WH, Potter C, Bailey R, Marsh K, Pinder M, Hill AV, Plebanski M. Identification of frequently recognized dimorphic T-cell epitopes in plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 in West and East Africans: lack of correlation of immune recognition and allelic prevalence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:194–203. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaneko O, Kimura M, Kawamoto F, Ferreira MU, Tanabe K. Plasmodium falciparum: allelic variation in the merozoite surface protein 1 gene in wild isolates from southern Vietnam. Exp Parasitol. 1997;86:45–57. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang Y, Long CA. Sequence heterogeneity of the C-terminal, Cysrich region of the merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP-1) in field samples of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;73:103–110. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branch OH, Udhayakumar V, Hightower AW, Oloo AJ, Hawley WA, Nahlen BL, Bloland PB, Kaslow DC, Lal AA. A longitudinal investigation of IgG and IgM antibody responses to the merozoite surface protein-1 19-kiloDalton domain of Plasmodium falciparum in pregnant women and infants: associations with febrile illness, parasitemia, and anemia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:211–219. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dodoo D, Theander TG, Kurtzhals JA, Koram K, Riley E, Akanmori BD, Nkrumah FK, Hviid L. Levels of antibody to conserved parts of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 in Ghanaian children are not associated with protection from clinical malaria. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2131–2137. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2131-2137.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egan AF, Morris J, Barnish G, Allen S, Greenwood BM, Kaslow DC, Holder AA, Riley EM. Clinical immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria is associated with serum antibodies to the 19-kDa C-terminal fragment of the merozoite surface antigen, PfMSP-1. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:765–769. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riley EM, Allen SJ, Wheeler JG, Blackman MJ, Bennett S, Takacs B, Schonfeld HJ, Holder AA, Greenwood BM. Naturally acquired cellular and humoral immune responses to the major merozoite surface antigen (PfMSP1) of Plasmodium falciparum are associated with reduced malaria morbidity. Parasite Immunol. 1992;14:321–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1992.tb00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh S, Miura K, Zhou H, Muratova O, Keegan B, Miles A, Martin LB, Saul AJ, Miller LH, Long CA. Immunity to recombinant plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP1): protection in Aotus nancymai monkeys strongly correlates with anti-MSP1 antibody titer and in vitro parasite-inhibitory activity. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4573–4580. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01679-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt P, Fawcett R, Carter R, Walliker D. Estimating SNP proportions in populations of malaria parasites by sequencing: validation and applications. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;143:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takala SL, Smith DL, Stine OC, Coulibaly D, Thera MA, Doumbo OK, Plowe CV. A high-throughput method for quantifying alleles and haplotypes of the malaria vaccine candidate Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 19 kDa. Malar J. 2006;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bejon P, Andrews L, Hunt-Cooke A, Sanderson F, Gilbert SC, Hill AV. Thick blood film examination for Plasmodium falciparum malaria has reduced sensitivity and underestimates parasite density. Malar J. 2006;5:104. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malhotra I, Dent A, Mungai P, Muchiri E, King CL. Real-time quantitative PCR for determining the burden of Plasmodium falciparum parasites during pregnancy and infancy. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3630–3635. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3630-3635.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermsen CC, Telgt DS, Linders EH, van de Locht LA, Eling WM, Mensink EJ, Sauerwein RW. Detection of Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites in vivo by real-time quantitative PCR. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;118:247–251. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00379-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNamara DT, Kasehagen LJ, Grimberg BT, Cole-Tobian J, Collins WE, Zimmerman PA. Diagnosing infection levels of four human malaria parasite species by a polymerase chain reaction/ligase detection reaction fluorescent micro-sphere-based assay. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:413–421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carnevale EP, Kouri D, Dare JT, McNamara DT, Mueller I, Zimmerman PA. A multiplex ligase detection reaction-fluorescent microsphere assay (LDR-FMA) for simultaneous diagnosis of single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;45:752–761. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01683-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qari SH, Shi YP, Goldman IF, Nahlen BL, Tibayrenc M, Lal AA. Predicted and observed alleles of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP-1), a potential malaria vaccine antigen. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;92:241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Withers MR, McKinney D, Ogutu BR, Waitumbi JN, Milman JB, Apollo OJ, Allen OG, Tucker K, Soisson LA, Diggs C, Leach A, Wittes J, Dubovsky F, Stewart VA, Remich SA, Cohen J, Ballou WR, Holland CA, Lyon JA, Angov E, Stoute JA, Martin SK, Heppner DG. Safety and reactogenicity of an MSP-1 malaria vaccine candidate: a randomized phase Ib dose-escalation trial in Kenyan children. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006;1:e32. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]