Abstract

Microsatellite markers derived from simple sequence repeats have been useful in studying a number of human pathogens, including the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Genetic markers for P. vivax would likewise help elucidate the genetics and population characteristics of this other important human malaria parasite. We have identified a locus in a P. vivax telomeric clone that contains simple sequence repeats. Primers were designed to amplify this region using a two-step semi-nested polymerase chain reaction protocol. The primers did not amplify template obtained from non-infected individuals, nor DNA from primates infected with the other human malaria parasites (P. ovale, P. malariae, or P. falciparum). The marker was polymorphic in P. vivax-infected field isolates obtained from Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and Guyana. This microsatellite marker may be useful in genetic and epidemiologic studies of P. vivax malaria.

INTRODUCTION

Human malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax rarely kills like P. falciparum, but it causes a debilitating febrile illness in approximately 90 million people each year. The severe and widespread morbidity associated with endemic P. vivax malaria in Asia and the Americas exacts a heavy social and economic cost.1 Malaria caused by P. vivax represents a significant re-emerging disease threat, and resistance to available therapies may be a dominant factor driving that trend.2 Definitive evaluation of therapeutic efficacy requires the ability to distinguish natural reinfection and relapse from recrudescence due to therapeutic interventions, as well as provide an instrument for examining P. vivax population dynamics.

Simple sequence repeats are ubiquitous in eukaryotic genomes and have been used to generate microsatellite markers for genetic studies of many organisms. Microsatellite loci are often polymorphic due to differences in length of these simple sequences. Simple sequences are abundant in the genome of the malaria parasite P. falciparum, and genetic markers derived from polymorphic microsatellite loci have been used to map traits and to investigate parasite population genetics;3–5 limited P. vivax population studies have become possible through identification in the merozoite surface protein 3 alpha locus.6 Anderson and others used 12 microsatellite markers to characterize P. falciparum in finger prick blood samples obtained in Papua New Guinea and showed they could reproducibly quantify multiple infections.7 In other studies, microsatellite genotyping of widely distributed parasite isolates has revealed differences in parasite genetic diversity and population differentiation between areas of high and low transmission intensity,8 and more recently predictions regarding the evolution and spread of polymorphism associated with chloroquine resistance9 have been made.

Both P. vivax and P. falciparum possess 14 chromosomes; P. vivax chromosomes appear to be significantly larger.10 The A/T content of the P. vivax genome is estimated to be approximately 60%,11 which is considerably lower than the 81% A/T content reported for P. falciparum.12 In comparative studies, significant regions of gene synteny are observed between P. vivax and P. falciparum.13 The purpose of this study was to identify polymorphic microsatellite loci in P. vivax, and to use the polymorphic locus or loci to characterize field isolates obtained from P. vivax-endemic regions in Southeast Asia, Melanesia, and South America.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmodium vivax sequences were obtained from two sources: 1) a 1.5-Mb telomeric YAC contig14 (GenBank accession number AL360354), and 2) 10,874 P. vivax genome survey sequences (GSS) from mung bean nuclease–digested genomic DNA libraries of the Salvador 1 and Belem P. vivax strains.15 Simple sequence repeats were identified by Tandem Repeat Finder16 analysis of the GSS database, and by BLASTX analysis of the GSS database using the query terms (TA)n, (TAA)n, (CA)n, or (CAA)n, (where n = 8–13), and by visual inspection of the entire YAC IVD10 sequence.

All study protocols were reviewed and approved by institutional review boards from all participating institutions. Informed consent was obtained from all human adult participants and from parents or legal guardians of minors. Blood samples were obtained from P. vivax-infected individuals in Indonesia and Guyana. Finger prick blood samples were absorbed onto Whatman (Clifton, NJ) filter paper and air-dried (blood blots). DNA prepared from blood blots was extracted as follows. A 3-mm2 square piece of blood-impregnated filter paper was excised using a razor and transferred to a tube containing approximately 50 µL of methanol and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. The methanol was removed and the sample-impregnated filter paper was allowed to air-dry completely. We then added 50 µL of distilled water to each sample, and heated the tube for 15 minutes at 95–100°C, vortexing occasionally during the incubation. Additional blood samples were obtained as part of malaria field studies in Papua New Guinea. Extraction of DNA from all Papua New Guinean samples was performed using the QIAamp 96 DNA blood kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Initial samples used to validate the specificity of the microsatellite described here were positive for P. vivax infection by microscopic examination of blood smears and by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) diagnosis targeting the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene sequence.17 As negative controls, we included DNA samples from uninfected individuals, and from primate blood samples infected with the three other human malaria parasites (P. falciparum, P. ovale, and P. malariae). A nested or semi-nested PCR strategy was used to amplify template DNA since levels of parasite infection are variable and often low. With this strategy, an aliquot of a nest 1 reaction was used as template in a subsequent nest 2 PCR targeting a smaller sequence contained within the first amplicon. In the semi-nested strategy used here, the primers used to amplify the YAC IVD10 microsatellite were as follows: for nest1, 5′-CAGAGAATTCTGTCCAATCATC-3′ (N1upstream) and 5′-CAGTAATCTAACATGGCTATTAG-3′ (N1downstream); and for nest 2, 5′-Cy5GTAAAAATTCGAAACATC-3′ (N2upstream) and 5′-TTTTATTCACAGTAAAGTGC-3′ (N2downstream). Genomic DNA (3 µL/sample) was combined with 1× PCR buffer (67 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 6.7 mM MgSO4, 16.6 mM NH4)2SO4, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), 30 pmoles of each of reverse and forward primers, 0.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase, 200 µM dNTP, and water (25-µL reaction volume). Forty cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds were completed for nest 1. For the nest 2 reaction of the nest 1 product, 3 µL was added to a mixture containing the appropriate nest 2 reagents and amplified by 25 cycles of a two-step PCR of 94°C for 30 seconds and 55°C for one minute. Aliquots of the PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide gel (7.7 M urea/32% formamide). Fluorescence signal (Cy5) from the microsatellites was visualized using a Storm 860 (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

RESULTS

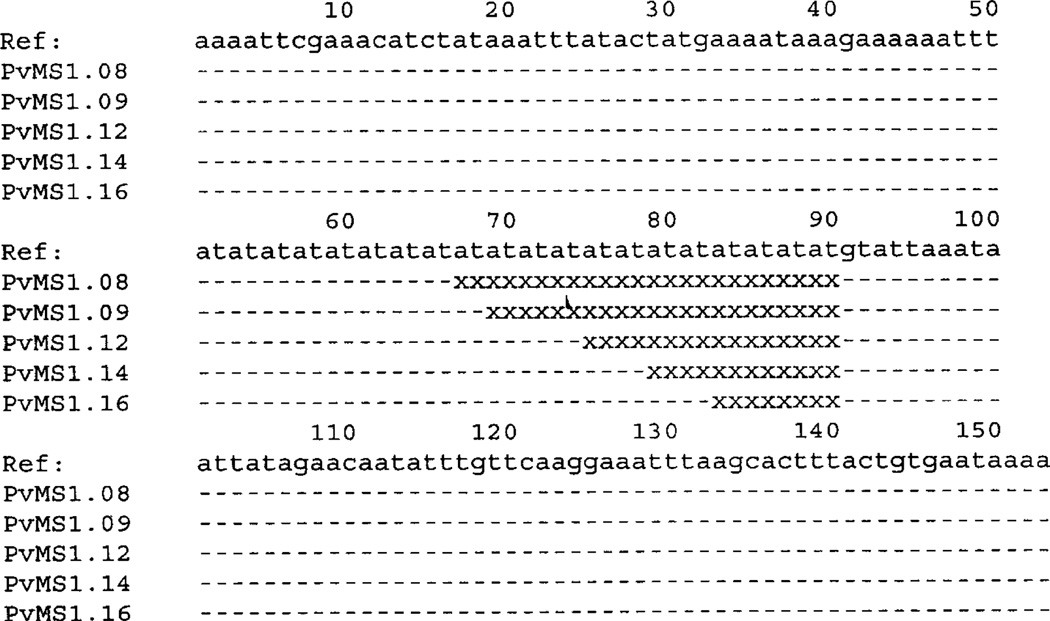

We identified a region (nucleotide positions 61123 to 61162) in the telomeric YAC clone IVD10 (GenBank Accession no. AL360354) that contained (AT)20. The microsatellite is located within the second exon of the vir13 pseudogene. Preliminary analyses suggested that the PCR products faithfully amplified from samples previously determined to be P. vivax-infected and did not amplify from samples from uninfected North Americans or samples known to be infected with other human Plasmodium species parasites. The DNA sequence analysis shown in Figure 1 confirmed that the amplicon was homologous to the reference sequence from IVD10. Comparison of individual clones further suggested that this sequence was polymorphic resulting from differences in the number of AT repeats (n = 8–20).

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of five Plasmodium vivax microsatellite (PvMS) alleles. Sequence alignments show the underlying length differences in the AT repeat length responsible for microsatellite mobility polymorphisms (an example is shown in Figure 2). − = nucleotide identity;×= deleted nucleotides. The microsatellite sequences shown were obtained from three different P. vivax strains (Sal1, Thai 3, and Pv2). The nucleotide sequences of the polymorphic P. vivax microsatellite sequences PvMS1.08, PvMS1.09, PvMS1.12, PvMS1.14, and PvMS1.16, have been assigned the GenBank Accession numbers AY289756, AY289757, AY289758, AY289759, and AY289760, respectively.

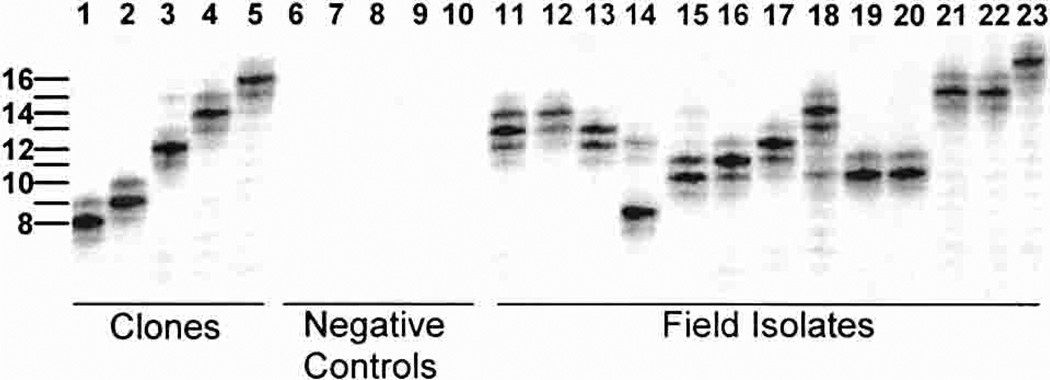

Results in Figure 2 provide examples of the microsatellite polymorphism observed from five sequenced clones (lanes 1–5), negative controls from two uninfected North Americans (lanes 6 and 7), P. falciparum, P. malariae, and P. ovale (lanes 8–10), and 13 P. vivax-infected individuals from Papua New Guinea (lanes 11–23). The band positions for the cloned sequences corresponded as predicted from the DNA sequence analysis. As indicated earlier in this report, we observed no evidence of PCR amplification from the negative control samples. The field isolates shown in Figure 2 exhibit allele size variation from 8 to 17 repeats. Some samples appear to be infected with more than one P. vivax strain, as shown by the presence of two or more high signal intensity bands (Figure 2, lanes 11, 13, and 15).

Figure 2.

Plasmodium vivax microsatellite polymorphism from Papua New Guinean field samples. Lanes 1–5 illustrate P. vivax microsatellite mobility polymorphisms for alleles identified in Figure 1. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of negative control samples are shown in lanes 6–10.The PCRs were performed using genomic DNA from P. falciparum (lane6), P. malariae (lane7), P. ovale (lane 8), and two human volunteers (lanes 9 and 10) who had not visited malaria-endemic regions. Lanes 11–23 illustrate microsatellite mobility polymorphisms observed in 13 P. vivax-infected individuals from East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea. Mixed P. vivax strain infections were suggested by multiple banding patterns in which secondary bands were at least 50% of the intensity of the strongest band. Examples of mixed P. vivax strain infections were observed in lanes 11, 13, and 15.

In a survey of 89 P. vivax-infected individuals from Papua New Guinea, we observed allele size variation from 7 to 24 repeats. Of the 15 different allelic products observed at this microsatellite locus (Table 1), the most frequent alleles from this survey were 11 (17 of 89 = 19.1%) and 12 (27 of 89 = 30.3%) AT repeats in length. At least four individuals showed evidence of infection by more than one P. vivax strain. The gene diversity (heterozygosity) for this microsatellite was calculated18 to be 0.85.

Table 1.

Plasmodium vivax microsatellite allelic polymorphism and frequencies

| Allele-specific AT repeat no. |

Total | Allele frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | 8 | 0.086 |

| 8 | 3 | 0.032 |

| 9 | 8 | 0.086 |

| 10 | 8 | 0.086 |

| 11 | 17 | 0.183 |

| 12 | 27 | 0.290 |

| 13 | 7 | 0.075 |

| 14 | 1 | 0.011 |

| 15 | 2 | 0.022 |

| 16 | 2 | 0.022 |

| 17 | 2 | 0.022 |

| 18 | 2 | 0.022 |

| 19 | 2 | 0.022 |

| 20 | 1 | 0.011 |

| 21 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 22 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 23 | 0 | 0.000 |

| 24 | 3 | 0.032 |

DISCUSSION

Further attempts were made to determine if additional polymorphic microsatellites could be amplified. Despite in silico screening of 5 Mb (approximately 20% of the complete genome from the P. vivax genome sequence data base; assumes a genome size of 26 Mb) and identification of several putative microsatellites, we were not able to confirm their presence in laboratory stocks of P. vivax, nor in field isolates by PCR amplification. This failure is likely due to several factors, among them contamination with host DNA and similarities across Plasmodium species’ genomes. Additional strategies for identifying microsatellite sequences may become clearer as the P. vivax genome sequencing project nears completion.11

In summary, the identification of additional polymorphic markers should enable investigators to address questions regarding the epidemiology and population structure of P. vivax, and host-parasite interactions. Moreover, the markers should improve assessments of therapeutic efficacy and ultimately contribute to development of more effective treatments needed for achieving control of a worsening trend in endemic malaria transmission.19

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the study volunteers for their willing participation. We also thank B. Keniboro and W. Kastens for fieldwork and sample acquisition, and K. Lorry for blood smear examination. Plasmodium species genomic DNA samples were kindly provided by Dr. William E. Collins (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA).

Financial support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant no. AI-46919).

Contributor Information

John C. Gomez, Department of Pathology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106-4983

David T. McNamara, The Center for Global Health and Diseases, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, W147D, 2109 Adelbert Road, Cleveland, OH 44106-4983

Moses J. Bockarie, Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research, PO Box 378, Madang, Papua New Guinea

J. Kevin Baird, Parasitic Diseases Program, U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit No. 2, American Embassy Jakarta, FPO AP 96520-8132.

Jane M. Carlton, Parasite Genomics Group, The Institute for Genomic Research, 9712 Medical Center Drive, Rockville, MD 20850

Peter A. Zimmerman, The Center for Global Health and Diseases, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, W147D, 2109 Adelbert Road, Cleveland, OH 44106-4983

REFERENCES

- 1.Mendis K, Sina BJ, Marchesini P, Carter R. The neglected burden of Plasmodium vivax malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64(suppl):97–106. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baird JK. Resurgent malaria at the millennium: control strategies in crisis. Drugs. 2000;59:719–743. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su X, Kirkman LA, Fujioka H, Wellems TE. Complex polymorphisms in an approximately 330 kDa protein are linked to chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum in Southeast Asia and Africa. Cell. 1997;91:593–603. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su X, Ferdig MT, Huang Y, Huynh CQ, Liu A, You J, Wootton JC, Wellems TE. A genetic map and recombination parameters of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 1999;286:1351–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferdig MT, Su XZ. Microsatellite markers and genetic mapping in Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:307–312. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01676-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce MC, Galinski MR, Barnwell JW, Snounou G, Day KP. Polymorphism at the merozoite surface protein-3alpha locus of Plasmodium vivax: global and local diversity. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:518–525. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson TJ, Su XZ, Bockarie M, Lagog M, Day KP. Twelve microsatellite markers for characterization of Plasmodium falciparum from finger-prick blood samples. Parasitology. 1999;119:113–125. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099004552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson TJ, Su XZ, Roddam A, Day KP. Complex mutations in a high proportion of microsatellite loci from the protozoan parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Ecol. 2000;9:1599–1608. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wootton JC, Feng X, Ferdig MT, Cooper RA, Mu J, Baruch DI, Magill AJ, Su XZ. Genetic diversity and chloroquine selective sweeps in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;418:320–323. doi: 10.1038/nature00813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlton JM, Galinski MR, Barnwell JW, Dame JB. Karyotype and synteny among the chromosomes of all four species of human malaria parasite. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;101:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlton J. The Plasmodium vivax genome sequencing project. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:227–231. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner MJ, Hall N, Fung E, White O, Berriman M, Hyman RW, Carlton JM, Pain A, Nelson KE, Bowman S, Paulsen IT, James K, Eisen JA, Rutherford K, Salzberg SL, Craig A, Kyes S, Chan MS, Nene V, Shallom SJ, Suh B, Peterson J, Angiuoli S, Pertea M, Allen J, Selengut J, Haft D, Mather MW, Vaidya AB, Martin DM, Fairlamb AH, Fraunholz MJ, Roos DS, Ralph SA, McFadden GI, Cummings LM, Subramanian GM, Mungall C, Venter JC, Carucci DJ, Hoffman SL, Newbold C, Davis RW, Fraser CM, Barrell B. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;419:498–511. doi: 10.1038/nature01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tchavtchitch M, Fischer K, Huestis R, Saul A. The sequence of a 200 kb portion of a Plasmodium vivax chromosome reveals a high degree of conservation with Plasmodium falciparum chromosome3. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;118:211–222. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.del Portillo HA, Fernandez-Becerra C, Bowman S, Oliver K, Preuss M, Sanchez CP, Schneider NK, Villalobos JM, Rajandream MA, Harris D, Pereira da Silva LH, Barrell B, Lanzer M. A superfamily of variant genes encoded in the sub-telomeric region of Plasmodium vivax. Nature. 2001;410:839–842. doi: 10.1038/35071118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlton JM, Muller R, Yowell CA, Fluegge MR, Sturrock KA, Pritt JR, Vargas-Serrato E, Galinski MR, Barnwell JW, Mulder N, Kanapin A, Cawley SE, Hide WA, Dame JB. Profiling the malaria genome: a gene survey of three species of malaria parasite with comparison to other apicomplexan species. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;118:201–210. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00371-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehlotra RK, Kasehagen LJ, Baisor M, Lorry K, Kazura JW, Bockarie MJ, Zimmerman PA. Malaria infections are randomly distributed in diverse holoendemic areas of Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:555–562. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sumawinata IW, Bernadeta, Leksana B, Sutamihardja A, Purnomo, Subianto B, Sekartuti, Fryauff DJ, Baird JK. Very high risk of therapeutic failure with chloroquine for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax malaria in Indonesian Papua. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:416–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]