Abstract

This paper presents the efficacy of the recruitment framework used for a clinical trial with sedentary family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. An integrated social marketing approach with principles of community-based participatory research provided the theoretical framework for organizing recruitment activities. This multi-pronged approach meant that caregivers were identified from a range of geographic locations and numerous sources including a federally funded Alzheimer’s disease center, health care providers, community based and senior organizations, and broad-based media. Study enrollment projections were exceeded by 11% and resulted in enrolling N = 211 caregivers into this clinical trial. We conclude that social marketing and community-based approaches provide a solid foundation for organizing recruitment activities for clinical trials with older adults.

Keywords: family caregiving, Alzheimer’s disease, participant recruitment, clinical trial

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) affects approximately 5.4 million Americans and is the fifth leading cause of death for older adults in the United States (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011). Because AD progressively impairs cognition and physical function and erodes normal behaviors, family caregivers for persons with AD face a broad range of care-related issues and potentially high levels of emotional, physical, and financial strain. Caregivers who are themselves older and experiencing these forms of strain present additional challenges for recruitment and enrollment into clinical trials.

Recruiting and enrolling older adults and especially older minorities into clinical trials is challenging as they are less likely to participate in trials as compared to younger and majority group counterparts (Arean, Alvidrez, Nery, Estes, & Linkins, 2003; Levkoff & Sanchez, 2003). Challenges often include (a) older adults’ limitations of activity and physical function; (b) medical treatments or comorbidities; (c) hospitalizations; or (d) the complicated nature of clinical trial inclusion and exclusion criteria (Norton, Breitner, Welsh, & Wyse, 1994; Resnick et al., 2003; Stahl & Vasquez, 2004; Sugarman, McCrory, & Hubal, 1998). These challenges may exist for caregivers of persons with AD, and challenges can be further compounded as these individuals face (a) frailty in their impaired family member; (b) lack of transportation; (c) inability to identify someone to be with the care recipient; (d) a general lack of time for additional activities such as enrolling in clinical trials; and 5) social isolation caused by the caregiving role (Dilworth-Anderson & Williams, 2004; Levkoff & Sanchez, 2003; Nichols et al., 2004).

The purpose of this paper is to describe how strained and sedentary family caregivers of persons with AD were recruited into the Telephone Resources and Assistance for Caregivers (TRAC) study, a lifestyle physical activity clinical trial. Specific aims were to (a) describe the combined theoretical approach utilized for TRAC participant recruitment; and (b) articulate the enablers and barriers faced in recruiting and subsequently enrolling these family caregivers into this clinical trial.

Methods

Telephone Resources and Assistance for Caregivers (TRAC) Study

The TRAC study was an 18-month randomized clinical trial for caregivers of persons with AD. TRAC was designed to determine if the Enhancing Physical Activity Intervention, which combines a caregiver skill-building intervention with a lifestyle physical activity program, was more effective in increasing lifestyle physical activity than the Caregiver Skill-Building Intervention control. The TRAC study built on the Stress Process Model (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990), and both interventions were guided by Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1997). Caregivers participated in a 12-month intervention during which they received one home intervention visit at baseline and 19 regular phone calls for a total of 20 contacts with a trained telephone counselor. Caregivers also completed data collection interviews at baseline, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 18 months. All study contacts were completed in the caregiver’s home or by telephone.

TRAC Recruitment Framework

This study used an integrated model for subject recruitment. First, we used multiple recruitment approaches because we were recruiting caregivers from a variety of settings and diverse cultural communities across a large geographic area. We knew we would need to work with numerous potential subjects and professionals in conjunction with varied recruitment approaches. Second, we anticipated that strained, sedentary caregivers might be isolated from community links such as churches and senior centers, which are often recruitment portals of entry. Recruitment approaches that did not depend on typical community engagement were needed. Third, in a recent systematic review the authors determined that social marketing alone or in conjunction with community outreach methods yielded the highest percentage of participants for many of the studies reviewed (UyBico, Pavel, & Gross, 2007). For these reasons, we developed a plan that integrated social marketing approaches with principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR).

Social marketing, which borrows from traditional business models, can be used as a successful person-centered research recruitment plan (Williams, Meisel, Williams, & Morris, 2011). In the research context, social marketing can refer to the application of commercial marketing techniques for the planning and execution of a recruitment plan for health behavior change interventions. Social marketing in a research setting can expand the typical “4 Ps” of commercial marketing (product, price, place, and promotion) to include working with partners to promote the study. In classical social marketing the product is the behavior, goods, service, or program exchanged for a price (Siegel & Doner, 1998). To successfully recruit participants, the intervention (product) must meet needs, wants, interests, or desires of the potential participants (Nichols et al., 2004). Price is the cost to the caregiver participants to engage in the behavior in question and can be monetary; may include time, effort, and lifestyle changes; or can be practical such as arranging respite services or care for the care recipient while the caregivers participate in a program (Siegel & Doner, 1998). For a research setting, place can be considered as the location where participants engage in the intervention (Nichols et al., 2004). Finally, promotions include advertising, media efforts, public relations events, selling, and other forms of communication about the product to the target audience (Siegel & Doner, 1998). In the context of research, the connection with partners is a key element. Partners are defined as other organizations that serve as a conduit to target audiences (Nichols et al., 2004). This model has been effective in recruiting a variety of populations, such as caregivers for the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) multisite clinical trial (Nichols et al., 2004).

Principles of CBPR are often used to recruit participants into clinical trials and were integrated with the social marketing framework for this study (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2005). CBPR techniques focus on a partnership approach that involves communities, organizations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process (Israel, et al., 2005; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). For CBPR, community is defined as a unit of identity, such as a family, social network, or geographic neighborhood (Israel, Parker, et al., 2005). In the case of TRAC recruitment, this could mean a caregiver support group, a neighborhood, a faith-based organization, or other senior service organizations.

There is increasing awareness of the strengths of using CBPRprinciples in research recruitment. Partnering with communities of any form for recruitment and implementation of interventions can enhance the ecological validity and effectiveness of health behavior change interventions (Bogart & Uyeda, 2009; Viswanathan et al., 2004). CBPR serves to match the perspectives of community groups and researchers by addressing both perspectives. Matching the perspectives and needs of key groups can be accomplished by involving all potential group partners in the research process, a central component of CBPR (Mendez-Luck, Trejo, Miranda, Jimenez, Quiter, & Mangione, 2011). Our recruitment plan is presented using the “5 P’s” of social marketing as mentioned above and showing how CBPR principles were incorporated into this plan.

Defining and identifying the target audience (potential participants)

Once the targeted audience is identified, appropriate recruitment plans can be developed and tailored to the population. Our target audience included strained and sedentary caregivers of persons with AD. Caregivers reported some to moderate levels of strain in providing care related to six activities of daily living (ADLs) and six instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), using a previously reported measurement strategy (strain = difficulty with ≥ 1 ADL/IADL; Schulz & Beach, 1999). Because the TRAC study proposed to increase physical activity, we enrolled sedentary caregivers, defined as individuals not participating in a regular program of exercise (<60 minutes per week). CBPR approaches focused on finding this “doubly-jeopardized” group of caregivers.

Developing the product

The TRAC intervention was the “product” designed to meet needs of strained, sedentary caregivers. In well-documented studies researchers have suggested that caregivers benefit from knowledge, but that skill-based interventions are associated with better intervention outcomes (Knight, Lutzky, & Macofsky-Urban, 1993; Sörensen, Pinquart, & Duberstein, 2002). Prior researchers have also shown that caregivers can be as physically active as non caregivers and also have the ability to increase their physical activity (Castro et al., 2007; Castro, Wilcox, O’Sullivan, Baumann, & King, 2002; Fredman, Bertrand, Martire, Hochberg, & Harris, 2006; King, Baumann, O’Sullivan, Wilcox, & Castro, 2002). Researchers also have shown that older adults, including caregivers of persons with AD, prefer physical activity programs of moderate intensity that are simple, convenient, inexpensive, and non-competitive (Connell & Janevic, 2009). Telephone interventions combined with home-based physical activity programs have also been shown to be effective for long-term adherence (Connell & Janevic, 2009; Farran et al., 2008; King & Brassington, 1997). An underlying assumption during TRAC development was that caregivers would need ongoing caregiving information, support, and skill-building in order to integrate self-care into their daily life and increase physical activity. Caregiver skill-building and enhancing physical activity content were integrated into the treatment intervention, creating a two-tiered product to address issues faced by both strained and sedentary caregivers (Farran et al., 2008).

A major concern with marketing any potential product is competition from other sources. Competing for caregivers’ time are care-related tasks, managing home and family needs, and possible employment roles. Yet many caregiver programs and interventions require that persons come to central locations, which means that caregivers need transportation and someone to stay with their impaired family member. To develop a caregiver-friendly product, TRAC used in-home data collection and intervention delivery to reduce transportation and respite care burden.

Managing the price

TRAC did not specifically focus on the monetary aspect of participation, nor did we provide financial incentives for participation, as both treatment and control interventions offered valuable information and support to caregivers. Social marketing considers cost to reflect issues such as the time and effort required for engaging caregivers in the desired behavior and suggests that caregivers must balance the costs of participation with the perceived benefits of participation, such as helping themselves or helping other caregivers in the future (Nichols et al., 2004; Siegel & Doner, 1998). Applying CBPR principles, we worked with community colleagues to understand and address the potential participant’s anticipated barriers and expected benefits of participating in this research. Of benefit to TRAC recruitment was the ability to minimize caregiver time cost by conducting all aspects of the study in caregivers’ homes and by telephone at their convenience (also see Section 4 below).

However, study participants incurred personal time costs to engage in data collection and implement the intervention. Study participants were expected to engage in a total of 26 contacts for a combination of data collection and intervention delivery. In addition, treatment group participants were also asked to engage in and monitor regular physical activity. This level of commitment to behavior change inherently takes time. We sought to offset these time costs: research assistants scheduled interviews flexibly, and all staff provided a listening ear in supporting caregivers in the challenges they face.

Improving accessibility (place)

TRAC enabled all study procedures to be delivered in the caregivers’ homes and by telephone. Interventions for caregivers of persons with AD are frequently conducted in locations such as memory clinics, dementia-specific organizations such as adult day programs, or other health care facilities. However, with a home-based intervention, we maximized accessibility to the program (place) and met the needs of caregivers who were unable to travel. Caregivers were not required to go to a central location for the intervention. Caregivers had no travel costs and did not have to find someone to be with their impaired family member during the intervention. They were able to participate at a time and duration that was convenient and worked best for them. They were also able to schedule intervention contacts and data collection times at their convenience, including evenings and weekends. Treatment group participants were also free to engage in physical activity at a time and for a duration that suited their preferences.

Working with partners to promote the study

To support our recruitment efforts with institutional and community partners, we used well-established community-based outreach strategies, as recognized by the National Institutes of Health (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2003). These strategies focused on building a broad base of community support for research and included collaborating with community leaders, forging close relationships with community organizations, attending community events, and maintaining ties with faith-based organizations (Moreno-John et al., 2004; Sood & Stahl, 2011; Stahl & Vasquez, 2004).

TRAC partners played a significant role in promoting the study and facilitating recruitment of participants as described in the results section. Study promotion included advertising and other forms of communication including letters, flyers, community presentations, and in health fairs where information was distributed about the product to the target audience (Siegel & Doner, 1998). The Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center (RADC) was an integral partner in our recruitment plan. The Center’s multicultural outreach programs focus on understanding the strengths and resources in local communities via the use of CBPR principles. Over many years, they have built a great deal of trust with important community gatekeepers and older adult leaders to maintain visibility and legitimacy in these areas. RADC staff frequently collaborates with a wide range of community-based organizations and have developed long-standing partnerships with groups across the Chicago area. Key staff maintains connections through involvement in multiple local senior organizations, serving on multiple community advisory boards, sponsoring the Southside Dementia Consortium and Senior Ministry Network and other community-based events, providing tailored educational programs to professionals working in multicultural communities, and joining city- and countywide task forces for older adult and minority issues.

Results

The following paragraphs describe selected aspects of how a theoretically supported integrated recruitment model supported TRAC recruitment efforts. Findings focus on integrating social marketing and CBPR principles in the following categories: study reach and participant characteristics, collaborative partnerships, and challenges to enrolling strained and sedentary caregivers in to TRAC.

Study Reach and Participant Characteristics

TRAC recruitment extended over a 37-month period and reached 327 persons, 288 of whom were eligible (88%). The study was successful in enrolling 211 strained and sedentary caregivers, 11% more than our targeted number. Baseline results suggest that the sample was similar to other caregiver studies in which caregivers’ ages averaged 61.6 (SD =12.1), and the caregivers were primarily female (81%), Caucasian (65%), and well-educated (52% college graduate or higher). Subjects most frequently were caring for a parent or other relative (57%); 43% were caring for a spouse. The sample also included 34% minorities, which exceeded the 30% targeted goal for minority participants.

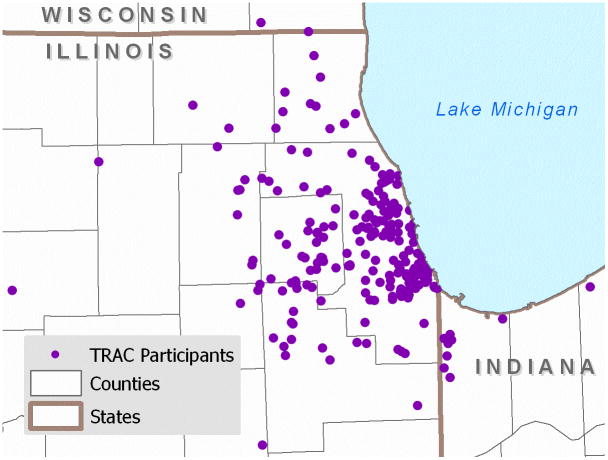

We enrolled participants from all 13 Chicago-area counties, including two counties in Indiana and one in Wisconsin (see Figure 1). Minority participants represented four Illinois counties and Lake County, Indiana. A total of 114 participants (54%) lived in census areas categorized as Northeastern Illinois Townships. We faced difficulty recruiting caregivers from low-income, densely populated townships (Illinois Poverty Summit, 2003). In seven of these townships, we only enrolled four caregivers.

Figure 1.

TRAC Study Geographic Distribution Across Metropolitan Chicago Area (Figure with the purple dots)

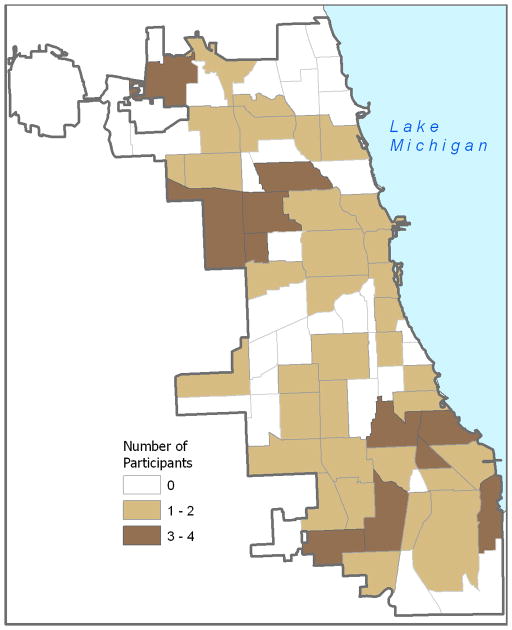

Although the majority of TRAC participants were from suburban areas (n = 112 or 53%), 81 out of the 211 participants (38%) resided in the city of Chicago (see Figure 2). We reached participants from numerous and diverse Chicago communities. There are 77 officially defined Chicago community areas, and we enrolled participants living in 45 (58%) of these communities (see Figure 2; City of Chicago, 2010). Of the 32 communities that were not represented in our sample, four have poverty rates exceeding 39%; an additional four communities have poverty rates between 22.1% and 33%, (Illinois Poverty Summit, 2003). Four of these communities also represent areas with the smallest percentages of older adults in the city (7.2% to 9.8%; Kamps, 2011). Most of the minority participants (75% or 53/71) lived in Chicago and represented 32 (42%) of the 77 Chicago community areas.

Figure 2.

TRAC Participants by Chicago Community Areas (Figure with beige-colored community areas)

Collaborative Partnerships

Recruitment methods used a combination of the social marketing framework and CBPR principles. Recruitment was directed by an experienced PhD-prepared Project Coordinator and required the ability to establish rapport with a wide range of professionals and use varying approaches depending upon the type of organization being contacted. Data are summarized from the most to least successful recruitment efforts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recruitment Sources (N=211)

| Enrolled | Minority enrolled | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

|

| |||||

| Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center and Rush University Medical Center | Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center | 133 | 63% | 47 | 22% |

| SoundCare (on-hold message system) | |||||

| Medical Center newsletters | |||||

| Rush Generations program | |||||

| Physician offices | |||||

| Broad-based community contacts | Senior centers | 32 | 15% | 4 | 2% |

| Adult day programs | |||||

| Churches, temples | |||||

| Senior living communities (including assisted living, skilled nursing, Continuing Care Retirement Communities) | |||||

| Geriatric care managers | |||||

| Professional associations | Alzheimer’s Association | 20 | 10% | 10 | 5% |

| Other caregiver organizations | |||||

| Community advertisements/other promotions | Local nursing publications | 18 | 8% | 10 | 5% |

| Mass mailing list | |||||

| Paid/unpaid advertisements | |||||

| Other media (not advertising) | |||||

| Other health care providers | Veteran’s Health | 8 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Administration | |||||

| Academic Medical Centers | |||||

| Alzheimer’s Disease Centers | |||||

| Local physicians | |||||

Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center and Rush University Medical Center

The majority of caregiver study participants (n = 132, 63%) came from the RADC, which played a major role in recruitment efforts (n = 102, 48.6% including n = 34, 16% minority participants; Table 1). Successful recruitment approaches built on longstanding CPBR principles included (a) staff review of clinic charts to determine minimum study eligibility criteria; (b) staff direct contact with patients/families seen in the clinic for diagnostic purposes; (c) staff mail contact with families in the IRB-approved data repository database, with study staff telephone follow-up; (d) direct recruitment of study participants from a young-onset Alzheimer’s disease support group; (e) direct access to multicultural outreach programs; and (f) mutually collaborative RADC and TRAC community presentations to potentially interested family caregivers. All efforts were carefully coordinated between RADC and TRAC staff; RADC staff attended carefully to ongoing communication, coordination, and “handing off” of participants to TRAC staff. Staff carefully tracked participant contacts and outcomes using a shared database.

Other Medical Center resources and services

Our integrated recruitment approach resulted in positive recruitment assistance from other medical center resources and services as well (Table 1). The most helpful approaches included (a) placement of a short advertisement on the medical center’s no-cost on-hold phone messaging system (n = 11, 5%); (b) placement of free advertisements in the medical center’s community newsletter and physician newsletter (n = 10, 5%); (c) The geriatric medicine department assisted with referrals for patients with a dementia diagnosis who were not seen through RADC (n = 9, 4%); and (d) the medical center senior program, Rush Generations, provided a free health-and-aging membership program for older adults and their caregivers. Study announcements were placed in their newsletters throughout the duration of the project. Collaborative presentations were also made during Rush Generations programs throughout the community.

Broad-based community contacts

Community-based approaches were used to “cast a broad net” and resulted in contacts with over 250 senior centers, faith-based organizations, senior living facilities, adult day care programs, and geriatric care managers (Table 1). In order to “give first” before expecting partners to give their time to us, we provided talks and lectures about the study, AD, and caregiving issues to 23 of these organizations. After direct recruitment through RADC, these organizations provided the next highest number of participants (n = 32, 15%). Targeted efforts were also possible with community-based organizations, as many organizations such as adult day programs and senior living facilities work directly with families coping with AD. These organizations also assisted with the recruitment of 4 (2%) minority participants.

Professional associations

We identified specific associations that deal directly with either AD or family caregivers, such as the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Family Caregivers Association. Local professional organizations and associations often hosted health fairs or other types of conferences designed for family caregivers or those with AD. When a conference was scheduled, we arranged to have a booth or table in which to promote the study. We were also able to communicate with other local association staff to have study information distributed through local listservs and newsletters. Through these sources, we enrolled n = 20 (9%) participants, including n = 9 (4%) minority participants (Table 1).

Community advertisements and other promotions

The following efforts were utilized to reach potentially large numbers of individuals. A total of n = 18 (9%) participants were enrolled as a result of advertisements; some were more successful than others. The study was listed nationally on http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, a registry of federally and privately supported clinical trials. TRAC was described in print in three local magazines and newspapers at no cost. Additionally, free advertisements were placed on local cable access channels in the city and suburbs during the final year of recruitment. Finally, purchasing a mass mailing address list allowed us to send letters to over 3,000 families who had expressed interest in AD issues, and this list yielded most of the participants in this category (n = 14 or 7% along with n = 9 or 4% minority).

Other health care providers

We had numerous opportunities to collaborate with other health care providers in the metropolitan area. We contacted three other geriatric departments in academic medical centers, along with a neuroscience institute and 12 local geriatricians and neurologists. Three Veterans Health Administration medical centers in the metropolitan area were also contacted to assist with participant recruitment. All of these sources were assessed as having an appropriate AD patient population. Individual providers were identified at each site, helping us to target our recruitment efforts and identify specific families. These sources yielded a total of n = 8 (4%) participants.

Challenges to Enrolling Strained Sedentary Caregivers

Although we identified 327 strained sedentary caregivers who were interested in the study, we faced additional challenges in actually enrolling these caregivers into the study once they were recruited (Table 2). The proposed inclusion criteria added a unique dimension to the study recruitment, which affected enrollment in different ways than commonly found in other caregiving studies. This study sought to enroll caregivers who were sedentary, yet who were interested and able to participate in physical activity. Finding caregivers with this combination was challenging. Almost one-third of excluded caregivers were too physically active to participate. On the other hand, few excluded caregivers said they were not interested in increasing their physical activity.

Table 2.

Challenges to Caregiver Recruitment and Enrollment (n=99 excluded)

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Caregiver issues | Too physically active | 29 | 29% |

| Lost after screening | 27 | 27% | |

| Low levels of strain/not enough care provided | 19 | 19% | |

| Physical condition prevented participation (i.e., medical comorbidities, physician didn’t approve participation) | 18 | 18% | |

| Not interested in increasing physical activity | 7 | 7% | |

| Care recipient issues | Confined to bed/too ill to participate | 4 | 4% |

| Did not have Alzheimer’s Disease | 2 | 2% | |

During screening, we inquired about caregivers’ chronic conditions, such as bone or joint problem (i.e., osteoarthritis), high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, cancer, or a psychiatric/mood disorder. Indication of one or more conditions and/or age > 69 required physician approval prior to participation in this physical activity intervention. There were 181 caregivers (55%) who required physician approval to participate, and 6% (n = 18) of screened caregivers had a medical condition such as hypertension or a physical disability that prevented participation. Other characteristics of this group created both individual and system level challenges to enrollment. These challenges included caregivers who had no regular source of medical care or were cared for by a range of specialists without a primary care provider. Some received care from large federal or county health care system in which obtaining physician approval could take up to one month, if received at all.

Care recipient health created barriers to a few caregivers’ enrollment in the study. Some excluded caregivers reported their care recipient was in the end stage of the disease, hospitalized, or had other competing health issues which made caregiver study participation impossible. Other excluded caregivers said their impaired family member did not have AD. See Table 2.

Finally, we wanted not only sedentary individuals, but those who reported strain with caregiving. Despite the well-documented stress and burden of caregivers, some of those excluded reported no strain or provided little hands-on care. See Table 2.

Although it was not expressed as a reason for nonparticipation, we discovered that 32 (15%) of TRAC participants were also providing care for other family members, and 72 (34%) were working full- or part-time in addition to acting as the primary caregiver for their impaired family member. Multiple caregiving or employment roles may have been a barrier for some individuals who never responded to our requests.

Discussion

The challenges of recruiting and enrolling older individuals in research studies have been well documented by a range of disciplines (Ross et al., 1999). Recruitment is generally known as one of the most difficult aspects of conducting clinical trials. Specific challenges to recruiting caregivers for persons with AD in to clinical trials may include caregiver physical or mental health, care recipient impairment, needing assistance with the care recipient at home during study implementation, and a lack of time and/or transportation for programs or interventions (Dilworth-Anderson & Williams, 2004; Nichols et al., 2004). As a result of these issues, an integrated recruitment plan is required for successful recruitment of study participants.

In the TRAC study we sought to enroll caregivers into a multi-component health promotion intervention. We used the social marketing framework in conjunction with adapted CBPR principles to develop a theoretically sound, multi-staged plan for participant recruitment, taking into account AD-related issues such as time, transportation, and care recipient physical and cognitive impairment. This integration allowed us to develop a comprehensive plan to address a full spectrum of participant, community, and study needs.

In TRAC we exceeded enrollment goals by 11% and enrolled 211 strained, sedentary caregivers, slightly higher than the enrollment in the REACH studies, in which s 63% to 104% of the recruitment goal were achieved (Nichols et al., 2004). Although participant sociodemographic characteristics were similar to those in other caregiving studies (Schulz et al., 2003), we were able to surpass our target to recruit 30% minority participants by enrolling 34%. These numbers also exceed the minority proportions in Cook County, Illinois, where 24.8% of the minority population was African American, 6.2% was Asian, and 24.0% was of Hispanic or Latino origin (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). The large sample with 34% minority participants also helped us to address potential threats to external validity.

Recruiting this diverse sample was primarily accomplished by utilizing CBPR principles via our collaboration with the RADC’s well-established research and multicultural outreach program. RADC is one of 29 nationally designated and funded Alzheimer’s disease research centers. A major focus of this entity is to support collaborative research efforts and recruitment of well-diagnosed subjects (in this case, the person with dementia) into research studies. A large part of RADC’s mission also focuses on family caregivers. This program has longstanding partnerships with local health care providers, clergy and religious organizations, and media sources—components deemed crucial for successful recruitment of multicultural participants (Williams et al., 2011). Over the course of the study, RADC staff promoted TRAC through numerous collaborative community events, programs, professional education programs and by working with key community leaders.

As evidenced by our geocoded maps, caregivers were from a wide geographic region of northeastern Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin, including diverse communities in the city of Chicago. Although other researchers have been successful in recruiting low-income older adults into clinical trials (Arean et al., 2003), it was difficult for us to recruit caregivers from the highest poverty areas in our region. RADC multicultural outreach staff have been trying for many years to gain an entry into the same communities in which we had difficulty recruiting. Staff members have found strong resistance to participation in research initiatives despite significant effort. This resistance is hypothesized to be due to longstanding negative perceptions of the medical center, general mistrust or misunderstanding of the scientific community, time limitations, economic constraints, and/or language and literacy barriers (Ejiogu, Norbeck, Mason, Cromwell, Zonderman & Evans, 2011; Levkoff et al., 2000; Moreno-John et al., 2004). Given the cumulative negative effects of poverty over a lifetime, it is imperative that future studies targeted to older adults focus on enrolling those from low income areas (Herrera, Snipes, King, Torres-Vigil, Goldberg & Weinberg, 2010).

In terms of developing the product, our study filled a gap in providing the services of an individually tailored intervention for caregivers. Regular physical activity has been known to assist in the prevention or delay in the onset of multiple chronic conditions (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1996). Researchers also have suggested that caregivers experience better intervention outcomes from skill-building programs, compared to strictly knowledge and education-based programs (Knight et al., 1993; Sörensen et al., 2002). We assumed caregivers would need caregiving information, support, and skill-building along with physical activity information. Through our community-based collaborative efforts, we came to understand that in order for caregivers to participate in the study, they wanted to complete the intervention and data collection interviews on their own schedules.

Neither price (costs) nor accessibility (place) made severe demands on participants; the entire intervention was conducted at the caregiver’s convenience in his or her own home. No visits to a central location were required, so caregivers did not have to travel, nor did they have to identify someone to be with the care recipient during the intervention.

We used an integrated approach to promote the study, which included contacts within our medical center and throughout the community (Nichols et al., 2004; Tarlow & Mahoney, 2000). As such, we identified numerous partners. We found that our most successful collaborations were with existing partners, emphasizing to us that addressing recruitment with a relationship-oriented approach is critical for success. Internal collaboration with our medical center was more fruitful than collaboration with external health care providers, as internal efforts reached large geographical areas and consisted of many potential participants (Tarlow & Mahoney, 2000). TRAC benefited from a long-established partnership between the College of Nursing and the RADC, which had mutual benefit to the clinic, researchers, and families. Other clinical trials may be unable to collaborate with such a center, or may lack substantial funds to reimburse facilities for recruitment efforts. There were also numerous no-cost recruitment options available through our medical center, which allowed us to reach a very large number of individuals.

Successful recruitment strategies with the RADC are based on the following three factors (a) long-established relationships between the Principal Investigator (Farran) and the RADC staff; (b) a well-established RADC infrastructure that emphasizes research recruitment into multiple studies; and (c) CBPR principles that fostered long-term community relationships and emphasizing “giving back” to a community before expecting research recruitment results. These principles include (a) community engagement to appear constantly visible to residents of numerous and diverse communities; (b) community giving to build trust with important community gatekeepers and older adult leaders (i.e., providing educational programs for health professionals in the communities in which we were trying to recruit, and working with local elected officials to identify needs of their constituents).

Internal advertisements and approaches reached a very large segment of patients and families and were available at no cost. The disadvantage was that these initial approaches did not identify all inclusion criteria and resulted in many phone inquiries from ineligible individuals.

Creating new partnerships with community agencies and professional associations to recruit for a clinical trial proved difficult. As with many interventions, we needed an internal champion to assist us with recruitment. Not surprisingly, when we “cold-called” agencies, it was difficult to get staff on board to recruit, and we did not receive return calls from many of these agencies. Indeed, new partner agencies may not have perceived any benefit to collaboration (Dowling & Wiener, 1997). Other less apparent barriers may have included: (a) There may have been conflict between the interests of academic institutions and those of provider agencies (Ejiogu et al., 2011; Levkoff & Sanchez, 2003; Levkoff et al., 2000); (b) Adult day programs, which served many individuals with AD, often had their clients “bussed” to their center and did not regularly meet with their families. Therefore, we were dependent on center staff to distribute study flyers and contact family members; (c) Geriatric care managers were easily identified, but they worked with many families in which the primary caregiver lived out of state; (d) Facilities’ financial challenges may have impeded their ability to assist with study recruitment. Many agencies in the area had lost funding and staff. Some organizations no longer had sites or telephone numbers.

Local advertisements and promotions reached many families not identified by other community sources and allowed dissemination of information to a very large segment of the population. However, as some of these contacts were not specifically targeted to older adults or caregivers, such efforts yielded surprisingly few enrolled participants. Paid advertising through area newspapers, radio, and television was determined to be too costly and unfocused.

We faced numerous barriers in attempting to collaborate with other health care providers. We recognized many competing interests and time demands. Physicians were also difficult to contact despite multiple attempts. In larger medical centers, the size of the organizations, bureaucratic issues, and the potential of perceived competition made recruitment quite difficult.

Although we developed a theoretically-based integrated recruitment plan, there were limitations to this plan. As we needed numerous community-based partners to successfully recruit our target population, we adapted principles from social marketing and added CBPR components (Bogart & Uyeda, 2009; Israel, Parker, et al., 2005; Viswanathan et al., 2004). These multiple models used together created a highly successful, multi-modal recruitment strategy. Yet despite these efforts, we were unable to enroll subjects from certain geographic regions for reasons that remain unclear.

As channels such as the National Family Caregiver Support Program continue to disseminate evidence-based caregiver interventions, we will need successful, collaborative recruitment. Given the expected exponential increase in persons with AD in the coming decades, it is critical to continue to focus on the health and wellbeing of the family caregivers who provide the majority of hands-on care. This focus may be facilitated by the recent passage of the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (Public Law 111-375, 2011), which will serve to coordinate and evaluate all efforts in Alzheimer’s research, clinical care, and programming. We find promise for future recruitment of persons with AD and family caregivers through the development and implementation of the TrialMatch™ program, recently introduced by the Alzheimer’s Association. The program is an online service to link persons with AD and their families with ongoing clinical trials.

The results of the TRAC recruitment plan demonstrate that a theoretically-based, multi-tiered approach to recruitment is required to successfully recruit caregivers for persons with Alzheimer’s disease into research studies. However, each trial has unique constraints that entail flexibility and creativity to address the needs of the target population. Innovative recruitment ideas and collaboration with providers can result in mutually beneficial results: researchers obtain needed participants and caregivers receive the services they need.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) Grant No. R01 NR009543. Special thanks to our collaborators with the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center (National Institute of Aging [NIA] Grant No. P30 AG010161 and the Illinois Department of Public Health), the Rush Institute for Healthy Aging and Nina L. Savar, GIS Coordinator, University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs.

Contributor Information

Caryn D. Etkin, Assistant Professor, College of Nursing, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois.

Carol J. Farran, Professor and The Nurses Alumni Association Chair in Health and the Aging Process, College of Nursing, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois.

Lisa L. Barnes, Associate Professor of Neurological Sciences and Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois.

Raj C. Shah, Assistant Professor and Director, Rush Memory Clinic, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2011 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7:208–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arean PA, Alvidrez J, Nery R, Estes C, Linkins K. Recruitment and retention of older minorities in mental health services research. Gerontologist. 2003;43:36–44. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L, Uyeda K. Community-based participatory research: Partnering with communities for effective and sustainable behavioral health interventions. Health Psychology. 2009;28:391–393. doi: 10.1037/a0016387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro CM, King AC, Housemann R, Bacak SJ, McMullen KM, Brownson RC. Rural family caregivers and health behaviors. Journal of Aging and Health. 2007;19:87–105. doi: 10.1177/0898264306296870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro CM, Wilcox S, O’Sullivan P, Baumann K, King AC. An exercise program for women who are caring for relatives with dementia. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:458–468. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- City of Chicago. Community area 2000 census profiles. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cityofchicago.org/city/en/depts/dcd/supp_info/community_area_2000censusprofiles.html.

- Connell CM, Janevic MR. Effects of a telephone-based exercise intervention for dementia caregiving wives. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;2(8):171–194. doi: 10.1177/0733464808326951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams SW. Recruitment and retention strategies for longitudinal African American caregiving research: The Family Caregiving Project. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16(Suppl 5):137S–156S. doi: 10.1177/0898264304269725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling GA, Wiener CL. Roadblocks encountered in recruiting patients for a study of sleep disruption in Alzheimer’s disease. IMAGE: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1997;29:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1997.tb01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejiogu N, Norbeck JH, Mason MA, Cromwell BC, Zonderman AB, Evans MK. Recruitment and retention strategies for minority or poor clinical research participants: Lessons from the healthy aging in neighborhoods of diversity across the life span study. Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl 1):S33–S45. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farran CJ, Staffileno BA, Gilley DW, McCann JJ, Li Y, Castro CM, King AC. A lifestyle physical activity intervention for caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2008;23:132–142. doi: 10.1177/1533317507312556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman L, Bertrand RM, Martire LM, Hochberg M, Harris EL. Leisure-time exercise and overall physical activity in older women caregivers and non-caregivers from the caregiver-SOF study. Preventive Medicine. 2006;43:226–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera AP, Snipes SA, King DW, Torres-Vigil I, Goldberg DS, Weinberg AD. Disparate inclusion of older adults in clinical trials: Priorities and opportunities for policy and practice change. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S105–S112. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Poverty Summit. Atlas of Illinois poverty. 2003 Retrieved from http://www.csu.edu/cerc/documents/AtlasofIllinoisPoverty_000.pdf.

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, Salvatore A, Minkler M, López J, Halstead S. Community-based participatory research: Lessons learned from the centers for children’s environmental health and disease prevention research. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113:1463–1471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen A, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kamps P. City of Chicago - Chicago department of family and support services: Total seniors 60+ by Chicago community area: 2009. 2011 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Baumann K, O’Sullivan P, Wilcox S, Castro CM. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on physiological, behavioral, and emotional responses to family caregiving: A randomized controlled trial. Journals of Gerontology: Series A: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 2002;57A:M26–M36. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.1.m26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Brassington G. Enhancing physical and psychological functioning in older family caregivers: The role of regular physical activity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;19:91–100. doi: 10.1007/BF02883325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG, Lutzky SM, Macofsky-Urban F. A meta-analytic review of interventions for caregiver stress: Recommendations for future research. Gerontologist. 1993;33:240–248. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Levkoff S, Sanchez H. Lessons learned about minority recruitment and retention from the centers on minority aging and health promotion. Gerontologist. 2003;43:18–26. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkoff SE, Levy BR, Weitzman PF. The matching model of recruitment. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2000;6:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Luck CA, Trejo L, Miranda J, Jimenez E, Quiter EA, Mangione CM. Recruitment strategies and costs associated with community-based research in a Mexican-origin population. Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl 1):S94–S105. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-John G, Gachie A, Fleming CM, Napoles-Springer A, Mutran E, Manson SM, Perez-Stable EJ. Ethnic minority older adults participating in clinical research: Developing trust. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16(Suppl 5):93s–123s. doi: 10.1177/0898264304268151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alzheimer’s Project Act. Public Law 111-375, 41 U.S.C. 11201, 124 Stat. 4100. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ375/html/PLAW-111publ375.htm.

- Nichols L, Martindale-Adams J, Burns R, Coon D, Ory M, Mahoney D, Winter L. Social marketing as framework for recruitment: Illustrations from the REACH study. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16(Suppl):157S–176S. doi: 10.1177/0898264304269727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton M, Breitner J, Welsh K, Wyse B. Characteristics of nonresponders in a community survey of the elderly. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1994;42:1252–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, Concha B, Burgess JG, Fine ML, West L, Baylor K, Magaziner J. Recruitment of older women: Lessons learned from the Baltimore hip studies. Nursing Research. 2003;52:270–273. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, Gillespie W, Russell I, Prescott R. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1999;52:1143–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The caregiver health effects study. JAMA. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Burgio L, Burns R, Eisdorfer C, Gallagher-Thompson D, Gitlin LN, Mahoney DF. Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH): Overview, site-specific outcomes, and future directors. Gerontologist. 2003;43:514–520. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, Doner L. Marketing public health: Strategies to promote social change. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sood JR, Stahl SM. Community engagement and the resource centers for minority aging research. Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl 1):S5–S7. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42:356–372. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl SM, Vasquez L. Approaches to improving recruitment and retention of minority elders participating in research: Examples from selected research groups including the National Institute on Aging’s resource centers for minority aging research. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16(Suppl):9S–17S. doi: 10.1177/0898264304268146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman J, McCrory D, Hubal R. Getting meaningful informed consent from older adults: A structured literature review of empirical research. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998;46:517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarlow BA, Mahoney DF. The cost of recruiting Alzheimer’s disease caregivers for research. Journal of Aging and Health. 2000;12:490–510. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Cook County QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau. 2011 Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/17/17031.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity and health: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Outreach notebook for the inclusion, recruitment and retention of women and minority subjects in clinical research. No. 03-7036) Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UyBico SJ, Pavel S, Gross CP. Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: A systematic review of recruitment interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:852–863. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0126-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Gartlehner G, Lohr K, Griffith D, Whitener L. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. No. 04-E022-2) Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MM, Meisel MM, Williams J, Morris JC. An interdisciplinary outreach model of African American recruitment for Alzheimer’s disease research. Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl 1):S134–S141. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]