An alanine dehydrogenase from B. megaterium WSH-002 was expressed in E. coli and purified. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of the recombinant enzyme were performed.

Keywords: alanine dehydrogenase, Bacillus megaterium

Abstract

Alanine dehydrogenase (l-AlaDH) from Bacillus megaterium WSH-002 catalyses the NAD+-dependent interconversion of l-alanine and pyruvate. The enzyme was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells and purified with a His6 tag by Ni2+-chelating affinity chromatography for X-ray crystallographic analysis. Crystals were grown in a solution consisting of 0.1 M HEPES pH 8.0, 12%(w/v) polyethylene glycol 8000, 8%(v/v) ethylene glycol at a concentration of 15 mg ml−1 purified protein. The crystal diffracted to 2.35 Å resolution and belonged to the trigonal space group R32, with unit-cell parameters a = b = 125.918, c = 144.698 Å.

1. Introduction

Alanine dehydrogenase (l-AlaDH), which has been isolated from vegetative cells and spores of various Bacillus species and some other bacteria (Hong et al., 1959 ▶; Zink & Sanwal, 1962 ▶; McCowen & Phibbs, 1974 ▶; O’Conner & Halvorson, 1961 ▶; Nitta et al., 1974 ▶; Germano & Anderson, 1968 ▶; Holmes et al., 1965 ▶), catalyses the reversible oxidative deamination of l-alanine to pyruvate. l-AlaDH is involved in various metabolic pathways and is known to be required for normal sporulation and development in B. subtilis and Myxococcus xanthus (Siranosian et al., 1993 ▶; Ward et al., 2000 ▶). In Bacillus sp., l-AlaDH is important in assimilating l-alanine as an energy source through the tricarboxylic acid cycle and plays an important role in carbon and nitrogen metabolism (Yoshida & Freese, 1970 ▶). The increased level of l-AlaDH is linked to the generation of alanine for peptidoglycan biosynthesis and maintenance of the NAD+ pool under conditions where the terminal electron acceptor oxygen becomes limiting (Starck et al., 2004 ▶; Hutter & Dick, 1998 ▶; Hutter & Singh, 1999 ▶; Betts et al., 2002 ▶).

B. megaterium is a rod-shaped, Gram-positive and mainly aerobic spore-forming bacterium that is widely found in diverse habitats from soil to seawater, sediment, rice paddies, honey, fish and dried food (Vary et al., 2007 ▶). It is an ideal industrial organism that has been used for more than 50 years. It can grow in a simple medium containing the majority of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates, formate and acetate. In addition, B. megaterium can stably maintain a variety of plasmid vectors and is a desirable cloning host for the production of some important and unusual exoenzymes for industrial applications because of its lack of external alkaline proteases.

l-AlaDH from B. megaterium is a 42 kDa protein according to the molecular weight of recombinant l-AlaDH from Bacillus sp. (Ohshima & Soda, 1990 ▶). In order to elucidate the biochemical properties of l-AlaDH from B. megaterium, crystals of l-AlaDH have been obtained. Here, we report the purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction data analysis of the recombinant l-AlaDH protein with a His6 tag. The three-dimensional structure of this protein is being determined.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning, expression and purification

The ald gene encoding l-AlaDH protein (GenBank accession No. gi:345442329) was amplified from B. megaterium WSH-002 genomic DNA using the primers 5′-TGCATATGGTGAAAATTGGAGTGCC-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGTTATGCTTGCTCTAATA-3′ containing NdeI and XhoI restriction sites (bold sequences). The amplified PCR products were digested with NdeI and XhoI and were subsequently inserted into pET-28a(+) (Novagen, USA). The recombinant pET-l-AlaDH plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) strain (Novagen, USA). The transformants were grown in 800 ml LB medium containing 50 µg ml−1 kanamycin at 310 K until the OD600 reached 0.6–0.8 and were then induced at 299 K overnight by the addition of 0.1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; final concentration).

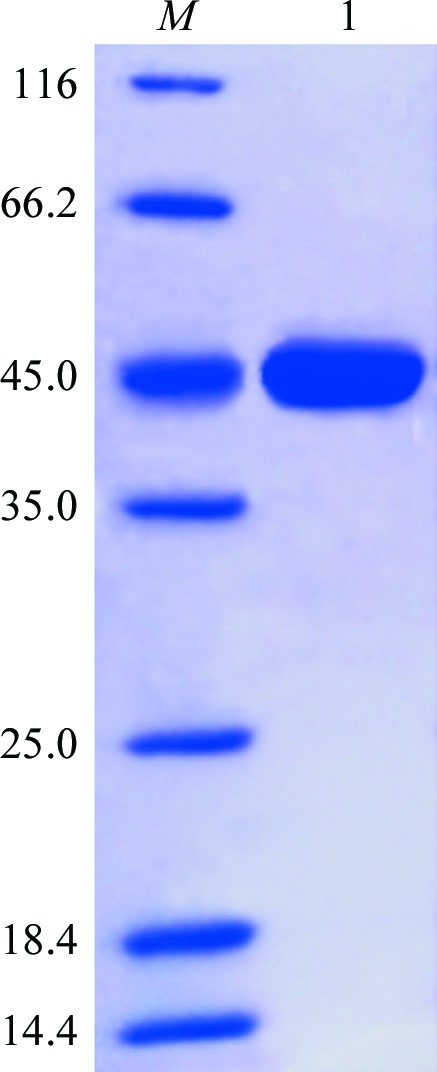

The IPTG-induced cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8600g for 30 min and were resuspended in 25 ml lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol). The cells were disrupted using a high-pressure homogenizer (JNBIO, People’s Republic of China) on ice and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 48 400g for 30 min. The supernatant was filtered and loaded onto an Ni2+-chelating affinity chromatography column (GE Healthcare, USA). The unbound proteins were rinsed with 50 ml wash buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 50 mM imidazole). The tightly bound proteins, which were mainly l-AlaDH protein, were eluted with 20 ml elution buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 100 mM imidazole). The eluted l-AlaDH protein was concentrated and further purified by size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare, USA). For crystallization purposes, fractions containing the l-AlaDH protein were dialysed against 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.0 and concentrated to 20 mg ml−1 by centrifugation at 277 K using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter device (Millipore, USA) with a 30 kDa molecular-weight cutoff. The purity of the protein was analysed by 12% SDS–PAGE (Fig. 1 ▶) and the protein concentration was determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA).

Figure 1.

12% SDS–PAGE analysis of l-AlaDH. Lane M, molecular-mass standards (labelled in kDa); lane 1, purified l-AlaDH protein (42 kDa).

2.2. Crystallization

Initial crystal screening was performed by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method using Crystal Screen, Crystal Screen 2, Index, SaltRx and PEG/Ion from Hampton Research at 289 K. The protein concentrations used for crystal screening were 5 and 10 mg ml−1. Trials were set up by mixing 1 µl protein solution with an equal volume of crystallization solution equilibrated against 200 µl reservoir solution. Crystallization conditions were optimized based on the initial screenings.

2.3. X-ray data collection and processing

For X-ray diffraction experiments, the crystals were quick-soaked in reservoir solution containing 15%(v/v) glycerol as a cryoprotectant for about 30 s. The soaked crystals were then mounted in loops and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen at 100 K (Parkin & Hope, 1998 ▶). The preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the crystals was performed on a Rigaku MicroMax-007 HF rotating-anode X-ray generator at a wavelength of 1.5418 Å. 720 frames were collected with 0.5° oscillation per image at 100 K. The diffraction data set was indexed, integrated and subsequently scaled using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). The data quality was assessed using SFCHECK (Vaguine et al., 1999 ▶) and the solvent content was calculated using MATTHEWS_COEF from CCP4 (Winn et al., 2011 ▶).

3. Results

The PCR product of the ald gene from B. megaterium was inserted into the expression vector pET-28a(+) and sequenced. The recombinant l-AlaDH protein with a His6 tag was successfully expressed in a soluble form and purified to electrophoretic homogeneity by Ni2+-chelating affinity and size-exclusion chromatography. The molecular weight of l-AlaDH was estimated to be 42 kDa by SDS–PAGE analysis (Fig. 1 ▶), coinciding with the calculated molecular weight of recombinant l-AlaDH with a His6 tag at the N-terminus.

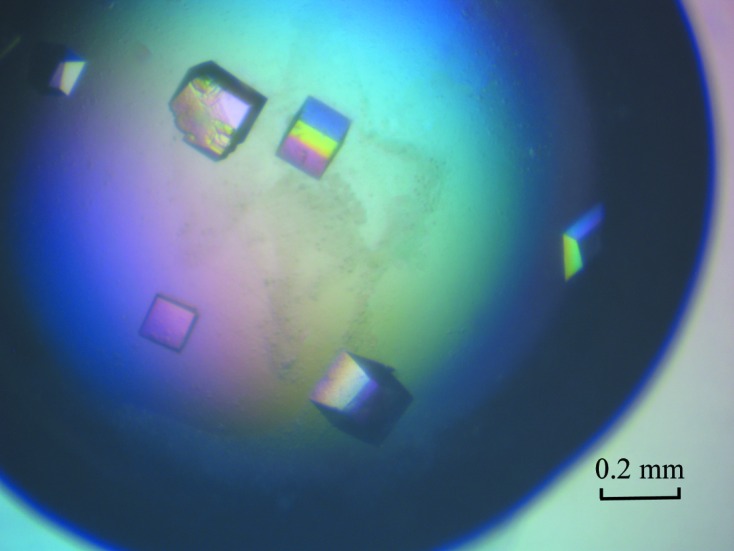

Initial crystallization screening was performed at 289 K by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method in 16-well tissue-culture plates. After 5–7 d incubation, crystals of different shapes were obtained in Crystal Screen 2 condition No. 37 (irregular polyhedra) and Index Screen condition Nos. 56 (irregular tetrahedra), 57 (irregular plates) and 77 (small needles). Condition No. 37 of Crystal Screen 2, which consists of 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, 10%(w/v) polyethylene glycol 8000, 8%(v/v) ethylene glycol, was optimized for structure determination according to preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the crystals. Optimization of this condition through adjustment of the protein concentration, reservoir pH and precipitant concentration yielded high-quality crystals with identical size and morphology. Crystals of about 200 × 180 × 150 µm in size (Fig. 2 ▶) grew with good reproducibility at 289 K in a solution consisting of 0.1 M HEPES pH 8.0, 12%(w/v) polyethylene glycol 8000, 8%(v/v) ethylene glycol at a protein concentration of 15 mg ml−1.

Figure 2.

Typical crystals of l-AlaDH protein (with dimensions of ∼200 × 180 × 150 µm).

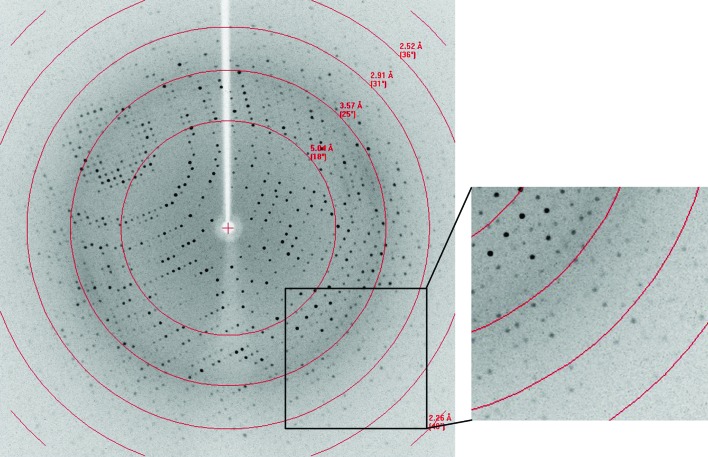

A diffraction data set was collected from the native l-AlaDH crystal to 2.35 Å resolution (Fig. 3 ▶) with an R merge of 7.3% using an in-house X-ray source. The crystallographic data statistics are summarized in Table 1 ▶. The crystal belonged to the trigonal space group R32, with unit-cell parameters a = b = 125.918, c = 144.698 Å, and contained one protein molecule per asymmetric unit. The Matthews coefficient was 1.47 Å3 Da−1, corresponding to a solvent content of 62.21% (Matthews, 1968 ▶).

Figure 3.

Typical X-ray diffraction pattern from an l-AlaDH crystal.

Table 1. Diffraction data statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the outermost resolution shell.

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 |

| Space group | R32 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = b = 125.918, c = 144.698, α = β = 90, γ = 120 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–2.35 (2.39–2.35) |

| R merge † (%) | 7.3 (34.4) |

| Average I/σ(I) | 26.8 (1.86) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.8 (96.1) |

| No. of observed reflections | 174287 (2160) |

| No. of unique reflections | 18346 (800) |

| Solvent content (%) | 62.21 |

R

merge =

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of the ith measurement of reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity of all symmetry-related reflections.

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of the ith measurement of reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity of all symmetry-related reflections.

Crystallographic model building and structure refinement are in progress. The l-AlaDH structure was phased by the molecular-replacement (MR) approach using AMoRe (Navaza, 1994 ▶) as implemented in the CCP4 package (Winn et al., 2011 ▶). Sequence alignment with known structures in the PDB showed that l-AlaDH from B. megaterium shares 62% sequence similarity with that from Thermus thermophilus (PDB code 2eez; RIKEN Structural Genomics/Proteomics Initiative, unpublished work). A search model for MR calculations was generated from 2eez in which non-identical amino-acid residues were replaced by alanine. A clear solution was obtained with an R free of 26.56% and an R work of 21.52% using data in the resolution range 50–2.35 Å. The three-dimensional structure of l-AlaDH will provide insights into the biochemical properties of this novel enzyme in B. megaterium and its important role in the reversible oxidative deamination of l-alanine to pyruvate.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Key Projects in the National Science and Technology Pillar Program–2012 National Biological Medicine International Innovation Garden Special (12ZCZDSY10600) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81102374).

References

- Betts, J. C., Lukey, P. T., Robb, L. C., McAdam, R. A. & Duncan, K. (2002). Mol. Microbiol. 43, 717–731. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Germano, G. J. & Anderson, K. E. (1968). J. Bacteriol. 96, 55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Holmes, P. K., Dundas, I. E. & Halvorson, H. O. (1965). J. Bacteriol. 90, 1159–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hong, M. M., Shen, S. C. & Braunstein, A. E. (1959). Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 36, 288–289. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hutter, B. & Dick, T. (1998). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 167, 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hutter, B. & Singh, M. (1999). Biochem. J. 343, 669–672. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCowen, S. M. & Phibbs, P. V. (1974). J. Bacteriol. 118, 590–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Navaza, J. (1994). Acta Cryst. A50, 157–163.

- Nitta, Y., Yasuda, Y., Tochikubo, K. & Hachisuka, Y. (1974). J. Bacteriol. 117, 588–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- O’Conner, R. J. & Halvorson, H. (1961). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 91, 290–299. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ohshima, T. & Soda, K. (1990). Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 42, 187–209. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Parkin, S. & Hope, H. (1998). J. Appl. Cryst. 31, 945–953.

- Siranosian, K. J., Ireton, K. & Grossman, A. D. (1993). J. Bacteriol. 175, 6789–6796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Starck, J., Källenius, G., Marklund, B. I., Andersson, D. I. & Akerlund, T. (2004). Microbiology, 150, 3821–3829. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vaguine, A. A., Richelle, J. & Wodak, S. J. (1999). Acta Cryst. D55, 191–205. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vary, P. S., Biedendieck, R., Fuerch, T., Meinhardt, F., Rohde, M., Deckwer, W. & Jahn, D. (2007). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 76, 957–967. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ward, M. J., Lew, H. & Zusman, D. R. (2000). J. Bacteriol. 182, 546–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

- Yoshida, A. & Freese, E. (1970). Methods Enzymol. 17, 176–181.

- Zink, M. & Sanwal, B. (1962). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 99, 72–77.