Abstract

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, are extremely variable in severity and have strong genetic components. In mice, several mutations are known to favor or inhibit intestinal inflammation. But a comprehensive picture of the pathogenesis of IBD cannot be assembled based on the limited information so far available from mouse genetic analyses, nor can human IBD be stringently ascribed to mutations known to be influential in mice. This review highlights recent progress made using mouse models created through a forward genetic approach towards the understanding of genes that normally prevent intestinal inflammation.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are the two major forms of chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and are diagnosed based on clinical, pathological, endoscopic and radiological features [1]. UC is confined to the colon and is marked by shallow, bleeding, inflamed ulcerations of the mucosa. CD is a granulomatous disease, often transmural and sometimes marked by formation of fistulae to other organs or to the abdominal wall. It may occur anywhere along the length of the GI tract. Both UC and CD typically begin in the second or third decade of life, and a majority of affected individuals progress to relapsing and remitting chronic disease [2]. UC and CD are relatively common and show a wide range of severity.

IBD depends upon host immunity, and both innate and adaptive immune systems have been implicated [3,4]. Evidence from animal models indicates that failure to suppress immunity to the abundant intestinal foreign antigen load can cause inflammation. Maintaining the normal balance between competence to respond to intestinal pathogens and suppression of inflammatory responses to commensal microbes appears to depend on the integrity of the mucosal and epithelial barriers [5–7], proinflammatory signalling pathways (especially via NF-κB) [8], and regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses in the intestine and draining lymphoid organs [9]. Disruption of any of these components has been shown to result in intestinal inflammation in animal models [2,4]. Defects in these components have also been implicated in human IBD, although fundamental knowledge of underlying pathogenesis remains poor. Even the most well-established causes of IBD, NOD2 mutations, elucidate pathogenesis only in a subset of white patients with ileal Crohn’s disease [2,4,10]. There is also evidence supporting a role for endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in intestinal inflammation (see below) [11,12••], and individual cytokines, notably TNF, are clearly important in IBD pathogenesis [13]. Monoclonal antibodies against TNF show a dramatic ame-liorative effect in at least some CD and UC patients [14•].

Microbes

IBD also depends upon microbial flora within the gut. Microbes may either initiate or perpetuate the inflammatory response in IBD [15]. Antibiotics can be used in patients with CD as adjunctive treatment. The essential role of microbes in IBD is best documented in mice, since in strains prone to spontaneous chronic colitis, disease is entirely dependent on the presence of the luminal flora. Thus, colitis is not observed when any of these lines are maintained in a germ-free state, but rapidly emerges when they are reconstituted with bacteria that are considered normal components of luminal flora [4,16]. Certain bacterial strains might be pro-inflammatory or antiinflammatory and therefore rational manipulation of the colonic flora of IBD patients might be a future treatment option. Bacterial species like Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus mirabilis have been shown to provoke colitis even in wildtype mice [17•,18]. On the other hand, Bacteroides fragilis protects mice from Helicobacter hepaticus induced colitis. This beneficial feature is mediated by the microbial molecule polysaccharide A.

Environment

Given the role of the microbiome in IBD causation, environmental factors strongly influence the development of IBD. For example, within a genetically homogenous Icelandic population, the incidence of CD increased sevenfold over a period of 45 years [19]. Only environmental or epigenetic factors could conceivably account for this, although it remains largely unknown which environmental factors are significant for disease development, with the exception of the use of tobacco [20]. Recent work in animal models suggests that viral infection (e.g. with norovirus) may play an important role in triggering inflammation in CD.

Genetics

IBD is a genetic disease, albeit with variable penetrance, probably owing to environmental factors, conceivably epigenetic factors as well. We know with certainty that IBD is heritable, because it runs in families [21,22], is observed at higher frequency within certain ethnic groups [23] and shows a high rate of concordance in identical twins [24–26]. The most fundamental questions about IBD concern its genetic etiology, since a clear understanding might provide new options for highly specific therapy. To date, most searches for causative mutations have been carried out in humans. Highly penetrant monogenic causes of IBD exist, but are rare. Homozygous null alleles of IL-10 and the IL-10 receptor have been shown to cause phenotypically classical CD [27•]. Because such examples of causation are hard to find, it is often stated that IBD is a complex genetic disorder. But while it clearly is a complex genetic disorder in some instances, it may have a monogenic etiology more often than we generally realize.

Genome scans carried out in several Caucasian populations around the world indicate that mutations affecting many genes are likely involved in predisposition to IBD, but these studies have been insufficient to establish cause and effect for any particular allelic variant of any individual gene. In fact, no mutation with an attributable relative risk higher than three has been discovered by the numerous scans reported so far [28]. Moreover, in aggregate, a high percentage of the genome is included within the genomic intervals implicated in these scans. On the other hand, it is necessary to keep in mind that whole genome association studies almost invariably miss certain types of genetic disorder. If recent, dominant or semidominant mutations are responsible for the disease phenotype, they will go undetected. And because many loci are haploinsufficient or otherwise vulnerable to dominant mutation, and 1–2 coding changes occur de novo at each generation in humans [29], viable semidominant phenotypes of recent origin are common.

In several studies, a striking excess of heterozygous mutations has been identified within candidate genes by direct sequence analysis of a diseased population. In such cases, semidominant changes were presumed to cause phenotypes of interest, among them susceptibility to Gram-negative infection [30], hypertension [31], and hypercholesterolemia [32]. In each instance, a sizeable proportion of population-wide phenovariance was ascribed to changes in one or several genes with related function. The same approach may detect semidominant alleles of genes responsible for a considerable proportion of IBD.

On the basis of our observations in mice (see below), semidominant mutations affecting MUC2 may have an etiological role in IBD. And more generally, we hypothesize that dominant deleterious alleles of numerous human genes may cause IBD.

At least some cases of IBD probably do reflect a complex genetic disorder: that is, a disorder caused by an unlucky combination of alleles at multiple loci. In the simplest case, two loci may be involved, but potentially there may be more than two. The conjoint effects of allelic variants at these loci are manifested as a disease. One likely example of a contributory locus is NOD2/CARD15, which was identified by several groups as a CD susceptibility gene based on classical genetic mapping studies in human populations [33,34]. However, while causally associated with CD, NOD2/CARD15 mutations are not sufficient for disease development. In the general population there are many more healthy individuals carrying the high-risk alleles than there are CD patients with the same polymorphism. Thus, even when NOD2/CARD15 mutations are present, pathogenic alleles at other loci must be combined with them in order for the disease phenotype to be expressed, or environmental or epigenetic effects must come into play [10,33].

In fact, there may be many different genetic etiologies of IBD, some monogenic and some polygenic. The ultimate challenge in IBD genetics is to identify all genes for which contributory pathogenic alleles exist.

Forward genetics as a means of defining the genetic target

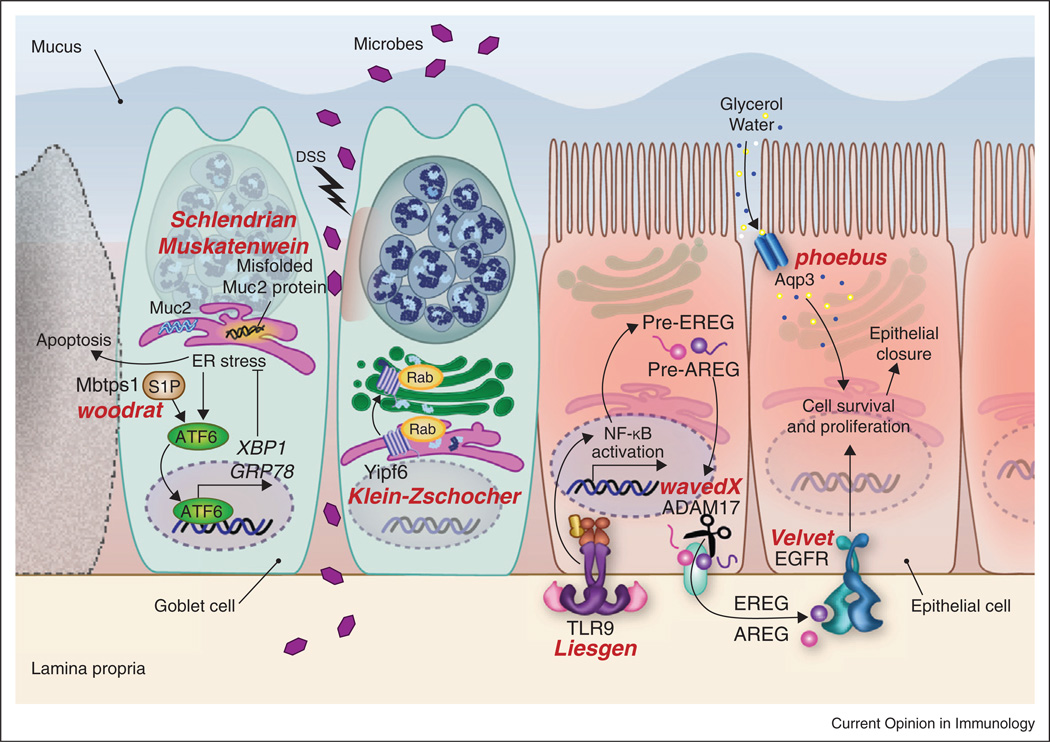

To unveil new genes important for the pathogenesis of IBD, we have taken an unbiased, hypothesis-free approach, using germline mutagenesis to analyze the phenomenon in mice. We screen for mutations that cause susceptibility to IBD on a defined genetic background, using dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) as an environmental sensitizing agent. We reason that at a low dose, DSS delivers an insult to epithelial integrity comparable to many that occur in nature. When an exceptional mouse is found to develop severe colitis, we positionally clone the causative mutation, determine whether the phenotype is caused by an effect of the mutation on the epithelium or hematopoietic system, and form testable hypotheses concerning the participation of the validated gene in the disease pathogenesis. Approximately 6000 mice have been screened to date by placing them on 1% DSS in drinking water for a period of seven days. A total of 15 transmissible mutations causing hypersensitivity to DSS have been detected. Of these, five have been identified, and fall into four gene categories, concerned with sensing microbes, proliferation of epithelial cells, accommodating ER stress and packaging specialized proteins within secretory vesicles. The genes discovered in this way, and their role in colitis, will be discussed in brief in the following sections.

Muc2

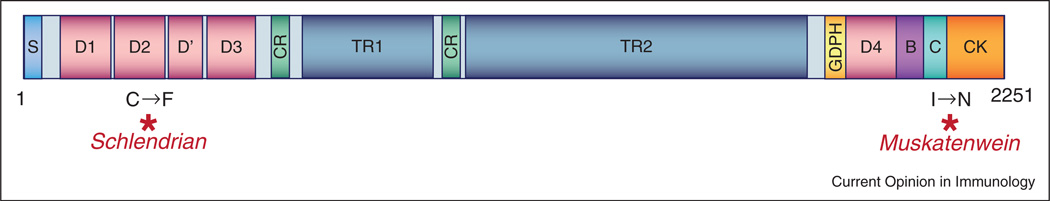

Two mutant mice (Schlendrian and Muskatenwein) exhibited semidominant phenotypes, and were found to have allelic mutations in the MUC2-encoding gene [50]. The Schlendrian mutation converts cysteine 561 to phenylalanine in the D2 domain of MUC2, while the Muskatenwein mutation causes an isoleucine to asparagine change at position 2172 near the C-terminal end of the protein, between the C domain and the cysteine knot (CK) domain (Figure 1). Both mutations cause severe, semidominant susceptibility to DSS induced colitis and the Schlendrian mutant develops spontaneous colitis as well when mice reach several months of age. McGuckin and coworkers earlier demonstrated that excessive ER stress, resulting from misfolding of the highly expressed MUC2 protein in goblet cells, is responsible for the colitis phenotype of Muc2 mutant mice [12••]. Several recent reports provide additional evidence for a causal role for ER stress in IBD.

Figure 1.

Domain structure of Mucin2. The Schlendrian mutation causes a cysteine to phenylalanine change in the D2 domain of the MUC2 protein. The Muskatenwein mutation alters an isoleucine residue located near the C-terminal end of the protein between the C domain and the cysteine knot (CK) domain. S = Signal sequence; D = D domains (homology to VWF; mediates trimerization); CR = Cysteine-rich domain; TR = Tandem repeat domain (heavily O glycosylated); GDPH = GDPH autocatalytic proteolytic site; B = B domain (homology to VWF); C = C domain (homology to VWF); CK = Cysteine-knot domain (homology to VWF; mediates dimerization).

Not only excessive ER stress, but an inadequate capacity for managing ER stress can also cause IBD. Mice lacking IRE1b, one of the key initiators of the unfolded protein response (UPR), are more susceptible to DSS-induced colitis [11]. Mice lacking XBP1 in epithelial cells display a loss of secretory Paneth cells and goblet cells in the intestinal epithelia, as well as spontaneous inflammation in the ileum. Moreover, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the XBP1 locus have been correlated with IBD in humans [35]. In addition, an ENU-induced hypo-morphic allele of the membrane bound site 1 protease (S1P)-encoding gene Mbtps1 caused increased sensitivity to induced colitis. S1P is required for the ATF6-mediated UPR to occur, and this may also be essential for prevention of IBD when injury is caused by DSS [36].

Aqp3

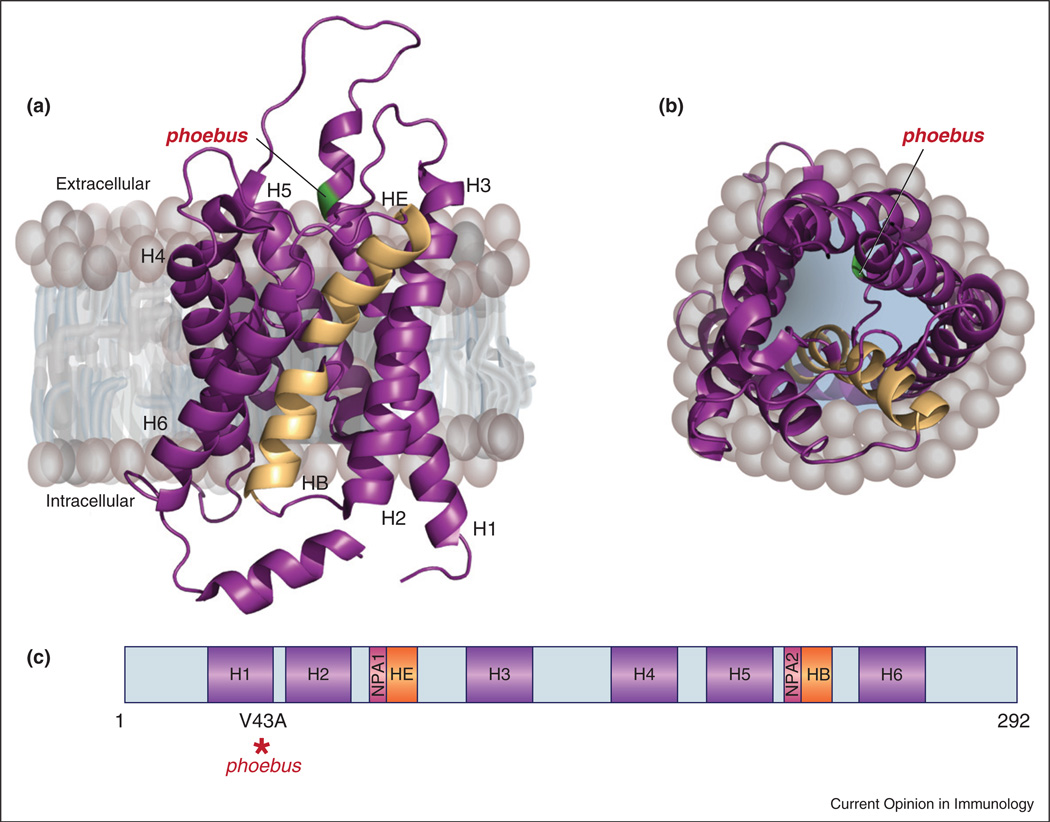

The recessive Phoebus mutation [50] causes death within five days of continuous exposure to DSS. The Phoebus mutation is a T to C transition at position 202 of the Aqp3 transcript resulting in a valine to alanine substitution at residue 43 of the aquaporin 3 protein (Figure 2). Aqua-porins mediate the rapid and selective transport of water across membrane lipid bilayers, allowing cells to regulate volume and internal osmotic pressure. AQP3 has an additional role in proliferation that has been reported for colonic epithelial cells, where it is expressed at the basolateral membrane [37]. Induction of colitis in AQP3 deficient mice by oral DSS or intracolonic acetic acid administration resulted in severe colitis after three days leading to death [37]. Aqp3 mutations cause diabetes insipidus as well, and one mechanism behind the colitis phenotype in AQP3 deficient mice is increased daily fluid consumption and therefore the increased DSS dosage. However, AQP3 deficient mice also showed increased susceptibility to DSS colitis when the DSS administration was normalized according to the average daily water intake of each genotype group [37].

Figure 2.

Protein and domain structure of AQP3. The phoebus mutation is modeled on AQP1, for which a crystal structure is available. (a) Side view of crystal structure of bovine AQP1 [47] (PDB ID: 1J4N). Transmembrane helices (H1–H6) are shown in purple; two membrane-inserted, nonmembrane spanning helices, HE and HB, are in light orange. The residue corresponding to the phoebus mutation, as shown in [47], is colored green. (b) Top view of AQP1 looking down into the cytosol. Models created with PyMOL. (c) Domain structure of AQP3. The position of the phoebus mutation in H1 is indicated by a red asterisk. NPA, asparagine–proline–alanine motif.

Enterocyte proliferation was greatly reduced in AQP3 null mice, presumably contributing to the reduced ability of these mice to cope with the damage induced by DSS. Oral glycerol treatment improved survival and reduced the severity of colitis in Aqp3 null mice [37], suggesting that glycerol transport may be important for enterocyte proliferation during colitis.

Toll-like receptors

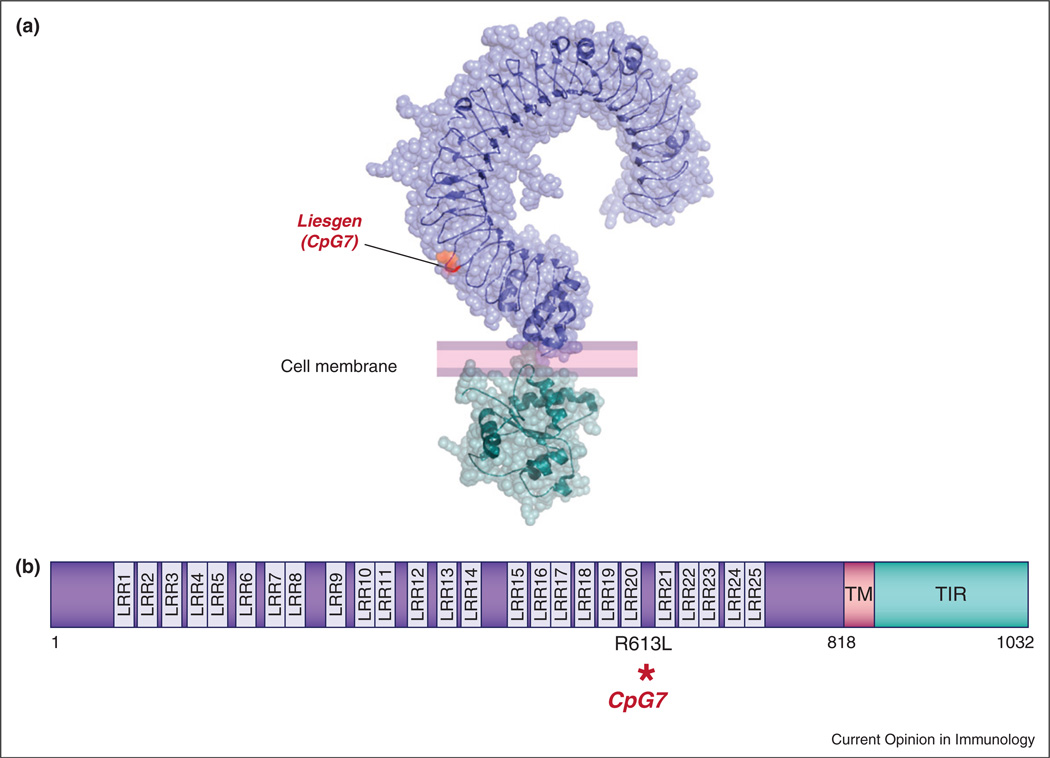

The Liesgen (aka CpG7) mouse [50] showed severe weight loss relative to wild type C57BL/6J mice and died after four days of continuous DSS administration. A G to T transversion was identified at position 1944 of the Tlr9 transcript on chromosome 9. The mutated nucleotide results in conversion of an arginine to a leucine at residue 613 of the TLR9 protein, in the twentieth leucine rich repeat (LRR) of the TLR9 ectodomain. TLR9 has twenty-five such repeats (Figure 3). Several reports have established an important role for TLR9 and other TLRs and components of the TLR signaling pathways in colitis. TLR2/3/4/5/9 and MyD88 deficient mice have a decreased tissue repair response during acute DSS damage [5,6,38–41]. We have recently demonstrated that TLR signaling plays an important role in nonhematopoietic cells, presumably cells of the gut epithelium, in which it induces biosynthesis of the EGF ligands amphiregulin (AREG) and epiregulin (EREG), triggering a protective response via EGFR in a model of DSS induced colitis [38]. A mutation in Adam17 (WavedX) was found to cause hypersusceptibility to DSS as well, apparently because Adam17, a matrix metalloproteinase also known as TNF-α converting enzyme (TACE), is necessary for post-translational processing of EGF family ligands, including AREG and EREG [42]. Moreover, mutations of Egfr (the dominant Velvet allele) or Areg or Ereg strongly sensitize mice to DSS [38,43,44].

Figure 3.

Protein and domain structure of TLR9. The CpG7 mutation is modeled on the TLR3 ectodomain, for which a crystal structure is available. (a) Crystal structures of the mouse TLR3 ectodomain [48] (PDB ID: 3CIG) and human TLR2 TIR domain [49] (PDB ID: 1FYW). The residue corresponding to the CpG7 mutation, as determined by BLAST alignment, is shown in orange. Model created with PyMOL. (b) TLR9 is a 1032 amino acid protein with an extracellular domain (purple) containing leucine rich repeats (LRR), a short transmembrane (TM) domain (pink) and a cytoplasmic Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain (teal). The position of the CpG7 mutation is shown.

Yipf6

The recessive Klein-Zschocher phenotype, also detected in DSS screening, was ascribed to a splicing mutation in Yipf6 (Ypt1p-interacting protein family member 6), a previously uncharacterized gene on the X-chromosome [45••]. The gene is predicted to encode a protein with a cytoplasmic N-terminal domain and a C-terminal domain containing five transmembrane a helices connected by short loops. Proteins of the Ypt1p-interacting protein 1 (Yip1) family are thought to regulate Rab protein-mediated ER to Golgi membrane transport (Figure 4). Klein-Zschocher mutant mice also develop spontaneous ileitis and colitis after sixteen months of age. Defective formation and secretion of large secretory granules by Paneth and goblet cells could account for impaired intestinal homeostasis in these mutant mice.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of mutations causing susceptibility to intestinal inflammation. By screening mice with ENU-induced mutations with a low dose of DSS, we have identified a number of components necessary for protecting against intestinal inflammation. These include TLR signaling, epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling, aquaporin 3 (Aqp3), the ER stress pathway that responds to unfolded proteins, and Yipf6, which is involved in formation and secretion of vesicles from Paneth and goblet cells. Allele names are in red; affected genes are in black.

As Yipf6 is highly expressed throughout the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in the colon, individual Yip1 family members may have tissue-specific functions [46]. Because the null allele of Yipf6 described here causes spontaneous disease, we suggest that YIPF6 should be regarded as a susceptibility locus when searching for causes of IBD in humans, particularly males.

The general picture that emerges

When DSS disrupts the epithelial barrier, microbes gain access to the lamina propria and trigger a response leading to repair as schematically illustrated in Figure 4. This response is minimally dependent upon TLR signaling, and a nonredundant requirement for several different TLRs is evident. Mutations in genes encoding several of the TLRs, in Unc93b1 (which permitsTLR3, 7, 8, and 9 transport from the ER to early endosomes in which signaling occurs), in MyD88, and in other components of the TLR signaling apparatus will prevent repair. TLR signaling is principally important because it leads to upregulation of Areg and Ereg. Biosynthesis of these EGF family ligands and their processing by Adam17 must occur to allow signaling via EGFR. EGFR signaling stimulates the proliferation of epithelial cell precursors, permitting closure of gaps in the epithelium. Also essential in this process is the uptake of water molecules by rapidly dividing cells, and the management of ER stress, particularly in goblet cells, which produce enormous amounts of MUC2 protein, especially when stimulated to do so by signals that result from epithelial injury. ER stress can be overwhelming if missense mutations prevent proper folding of MUC2, or if mutations affecting the UPR pathway are present. In either case, cell death may occur, with failure to close epithelial gaps. Certain molecules released by Paneth cells are also critical for resolving injury. These could include antimicrobial pep-tides present in the large granules of these cells, which fail to form in Yipf6 mutant mice. Absent such proteins the inoculum sustained during DSS injury may be too large for the host to cope with.

Conclusion

What mutations cause IBD? And what molecular processes normally prevent it? The former question has only a few answers. Monogenic causes of IBD have been elucidated in specific instances [27•], and many loci may be at risk of mutation. ENU mutagenesis would suggest that this is the case. Humans do not normally encounter DSS, but injury to the gut epithelium does occur on occasion, and it may be that some individuals are incapable of resolving it. It is interesting to see that when DSS is used in an unbiased sensitized screen, the mutations that cause severe colitis affect genes involved in epithelial repair. Could lesions in such genes be important causes of IBD in humans? As the list of such genes grows longer, DNA sequencing may provide a definitive answer.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank E.M. Moresco for critical reading of the manuscript and V. Webster for help with illustrations. This research was supported by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation through a Career Development Award to K.B., and by NIH BAA Contract HHSN27220000038C.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:417–429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Podolsky DK. Innate immunity in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5577–5580. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i42.5577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sartor RB. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3:390–407. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukata M, Michelsen KS, Eri R, Thomas LS, Hu B, Lukasek K, Nast CC, Lechago J, Xu R, Naiki Y, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 is required for intestinal response to epithelial injury and limiting bacterial translocation in a murine model of acute colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1055–G1065. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00328.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown SL, Riehl TE, Walker MR, Geske MJ, Doherty JM, Stenson WF, Stappenbeck TS. Myd88-dependent positioning of Ptgs2-expressing stromal cells maintains colonic epithelial proliferation during injury. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:258–269. doi: 10.1172/JCI29159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nenci A, Becker C, Wullaert A, Gareus R, van Loo G, Danese S, Huth M, Nikolaev A, Neufert C, Madison B, et al. Epithelial NEMO links innate immunity to chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2007;446:557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature05698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iqbal N, Oliver JR, Wagner FH, Lazenby AS, Elson CO, Weaver CT. T helper 1 and T helper 2 cells are pathogenic in an antigen-specific model of colitis. J Exp Med. 2002;195:71–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.2001889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hugot JP, Zouali H, Lesage S. Lessons to be learned from the NOD2 gene in Crohn’s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:593–597. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Hendershot LM, Harding HP, Ron D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:326–332. doi: 10.1038/35014014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heazlewood CK, Cook MC, Eri R, Price GR, Tauro SB, Taupin D, Thornton DJ, Png CW, Crockford TL, Cornall RJ, et al. Aberrant mucin assembly in mice causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and spontaneous inflammation resembling ulcerative colitis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e54. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050054. First demonstration that aberrant ER stress in mice can lead to spontaneous disease. The authors found that ENU-induced mutations in Muc-2 develop spontaneous colitis.

- 13.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N EnglJ Med. 2009;361:2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ordas I, Mould DR, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease: pharmacokinetics-based dosing paradigms. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:635–646. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.328. This review provides an excellent overview of the pharmacologic data available for different anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies.

- 15.Salzman NH, Bevins CL. Negative interactions with the microbiota: IBD. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;635:67–78. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09550-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Hao L, Medzhitov R. Role of toll-like receptors in spontaneous commensal-dependent colitis. Immunity. 2006;25:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garrett WS, Gallini CA, Yatsunenko T, Michaud M, DuBois A, Delaney ML, Punit S, Karlsson M, Bry L, Glickman JN, et al. Enterobacteriaceae act in concert with the gut microbiota to induce spontaneous and maternally transmitted colitis. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.004. This paper reveals two distinct microbes, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus mirabilis, correlating with colitis in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis using T-bet(−/−)xRag2(−/−) mice (see Ref. [18]).

- 18.Garrett WS, Lord GM, Punit S, Lugo-Villarino G, Mazmanian SK, Ito S, Glickman JN, Glimcher LH. Communicable ulcerative colitis induced by T-bet deficiency in the innate immune system. Cell. 2007;131:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjornsson S, Johannsson JH. Inflammatory bowel disease in Iceland, 1990–1994: a prospective, nationwide, epidemiological study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:31–38. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cosnes J. Tobacco and IBD: relevance in the understanding of disease mechanisms and clinical practice. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:481–496. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Binder V. Genetic epidemiology in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 1998;16:351–355. doi: 10.1159/000016891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Binder V, Orholm M. Familial occurrence and inheritance studies in inflammatory bowel disease. Neth J Med. 1996;48:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0300-2977(95)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duerr RH. Update on the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:358–367. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spehlmann ME, Begun AZ, Burghardt J, Lepage P, Raedler A, Schreiber S. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in a German twin cohort: results of a nationwide study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:968–976. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halfvarson J, Jess T, Bodin L, Jarnerot G, Munkholm P, Binder V, Tysk C. Longitudinal concordance for clinical characteristics in a Swedish-Danish twin population with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1536–1544. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halme L, Paavola-Sakki P, Turunen U, Lappalainen M, Farkkila M, Kontula K. Family and twin studies in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3668–3672. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i23.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Klein C, Shah N, Grimbacher B. IL-10 and L-10 receptor defects in humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1246:102–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06339.x. This review summarizes recent work on IL-10 or IL-10 receptor deficiencies in humans, and supports the hypothesis that IBD can be a monogenic disorder.

- 28.Budarf ML, Labbe C, David G, Rioux JD. GWA studies: rewriting the story of IBD. Trends Genet. 2009;25:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nachman MW, Crowell SL. Estimate of the mutation rate per nucleotide in humans. Genetics. 2000;156:297–304. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smirnova I, Mann N, Dols A, Derkx HH, Hibberd ML, Levin M, Beutler B. Assay of locus-specific genetic load implicates rare Toll-like receptor 4 mutations in meningococcal susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6075–6080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031605100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji W, Foo JN, O’Roak BJ, Zhao H, Larson MG, Simon DB, Newton-Cheh C, State MW, Levy D, Lifton RP. Rare independent mutations in renal salt handling genes contribute to blood pressure variation. Nat Genet. 2008;40:592–599. doi: 10.1038/ng.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen JC, Kiss RS, Pertsemlidis A, Marcel YL, McPherson R, Hobbs HH. Multiple rare alleles contribute to low plasma levels of HDL cholesterol. Science. 2004;305:869–872. doi: 10.1126/science.1099870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cezard JP, Belaiche J, Almer S, Tysk C, O’Morain CA, Gassull M, et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, Britton H, Moran T, Karaliuskas R, Duerr RH, et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, Glickman JN, Zeissig S, Tilg H, Nieuwenhuis EE, Higgins DE, Schreiber S, Glimcher LH, et al. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134:743–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brandl K, Rutschmann S, Li X, Du X, Xiao N, Schnabl B, Brenner DA, Beutler B. Enhanced sensitivity to DSS colitis caused by a hypomorphic Mbtps1 mutation disrupting the ATF6-driven unfolded protein response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3300–3305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813036106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiagarajah JR, Zhao D, Verkman AS. Impaired enterocyte proliferation in aquaporin-3 deficiency in mouse models of colitis. Gut. 2007;56:1529–1535. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.104620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandl K, Sun L, Neppl C, Siggs OM, Le Gall SM, Tomisato W, Li X, Du X, Maennel DN, Blobel CP, et al. MyD88 signaling in nonhematopoietic cells protects mice against induced colitis by regulating specific EGF receptor ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19967–19972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014669107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cario E, Gerken G, Podolsky DK. Toll-like receptor 2 controls mucosal inflammation by regulating epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1359–1374. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rachmilewitz D, Katakura K, Karmeli F, Hayashi T, Reinus C, Rudensky B, Akira S, Takeda K, Lee J, Takabayashi K, et al. Tolllike receptor 9 signaling mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of probiotics in murine experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:520–528. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vijay-Kumar M, Wu H, Aitken J, Kolachala VL, Neish AS, Sitaraman SV, Gewirtz AT. Activation of toll-like receptor 3 protects against DSS-induced acute colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:856–864. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Reddy P, Stocking KL, Sunnarborg SW, Lee DC, Russell WE, Castner BJ, Johnson RS, Fitzner JN, et al. An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science. 1998;282:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee D, Pearsall RS, Das S, Dey SK, Godfrey VL, Threadgill DW. Epiregulin is not essential for development of intestinal tumors but is required for protection from intestinal damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8907–8916. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8907-8916.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Troyer KL, Luetteke NC, Saxon ML, Qiu TH, Xian CJ, Lee DC. Growth retardation, duodenal lesions, and aberrant ileum architecture in triple null mice lacking EGF, amphiregulin, and TGF-alpha. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:68–78. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.25478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brandl K, Tomisato W, Li X, Neppl C, Pirie E, Falk W, Xia Y, Moresco EM, Baccala R, Theofilopoulos AN, et al. Yip1 domain family, member 6 (Yipf6) mutation induces spontaneous intestinal inflammation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210366109. This paper shows that Yipf6, a protein with no previously reported function in mammals, is essential for Paneth and goblet cells to develop their large granules. Furthermore, mice with a mutation in Yipf6 develop spontaneous intestinal inflammation.

- 46.Tang BL, Ong YS, Huang B, Wei S, Wong ET, Qi R, Horstmann H, Hong W. A membrane protein enriched in endoplasmic reticulum exit sites interacts with COPII. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40008–40017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sui H, Han BG, Lee JK, Walian P, Jap BK. Structural basis of water-specific transport through the AQP1 water channel. Nature. 2001;414:872–878. doi: 10.1038/414872a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu L, Botos I, Wang Y, Leonard JN, Shiloach J, Segal DM, Davies DR. Structural basis of toll-like receptor 3 signaling with double-stranded RNA. Science. 2008;320:379–381. doi: 10.1126/science.1155406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu Y, Tao X, Shen B, Horng T, Medzhitov R, Manley JL, Tong L. Structural basis for signal transduction by the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domains. Nature. 2000;408:111–115. doi: 10.1038/35040600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arnold CN, Barnes MJ, Berger M, Blasius AL, Brandl K, Croker B, Crozat K, Du X, Eidenschenk C, Georgel P, et al. ENU, mutations, and phenovariance in mice: inferences from 587 mutations. BMC Research Notes. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-577. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]