Abstract

Background

Purified protein derivative (PPD) has been used for more than half a century as an antigen for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection based on delayed type hypersensitivity. Although designated as “purified,” in reality, the composition of PPD is highly complex and remains ill-defined. In this report, high resolution mass spectrometry was applied to understand the complexity of its constituent components. A comparative proteomic analysis of various PPD preparations and their functional characterization is likely to help in short-listing the relevant antigens required to prepare a less complex and more potent reagent for diagnostic purposes.

Results

Proteomic analysis of Connaught Tuberculin 68 (PPD-CT68), a tuberculin preparation generated from M. tuberculosis, was carried out in this study. PPD-CT68 is the protein component of a commercially available tuberculin preparation, Tubersol, which is used for tuberculin skin testing. Using a high resolution LTQ-Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer, we identified 265 different proteins. The identified proteins were compared with those identified from PPD M. bovis, PPD M. avium and PPD-S2 from previous mass spectrometry-based studies. In all, 142 proteins were found to be shared between PPD-CT68 and PPD-S2 preparations. Out of the 354 proteins from M. tuberculosis–derived PPDs (i.e. proteins in either PPD-CT68 or PPD-S2), 37 proteins were found to be shared with M. avium PPD and 80 were shared with M. bovis PPD. Alignment of PPD-CT68 proteins with proteins encoded by 24 lung infecting bacteria revealed a number of similar proteins (206 bacterial proteins shared epitopes with 47 PPD-CT68 proteins), which could potentially be involved in causing cross-reactivity. The data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD000377.

Conclusions

Proteomic and bioinformatics analysis of different PPD preparations revealed commonly and differentially represented proteins. This information could help in delineating the relevant antigens represented in various PPDs, which could further lead to development of a lesser complex and better defined skin test antigen with a higher specificity and sensitivity.

Keywords: Biomarker, Broad spectrum antibiotics, Epitope, LC-MS/MS, Mantoux test

Background

Around 2 billion people in the world are infected with M. tuberculosis. According to WHO world TB (tuberculosis) control report 2011, in 2010 alone, 9 million new TB cases were reported and 1.45 million deaths occurred worldwide. Tuberculosis is the second most common infectious killer disease after HIV. One in five of the 1.8 million AIDS related deaths are estimated to be associated with TB. Tuberculin skin test (TST) is the standard test for the diagnosis of TB infection in the Western world [1]. American Thoracic Society and Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommend targeted TST for deciding the treatment regimen among groups associated with increased risk for progression of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) to active TB [2]. Vaccination is an important preventive measure to control community load of TB. An attenuated strain of M. bovis known as Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) is universally employed as a vaccine against TB. However, efficacy of BCG is controversial as it does not protect against adult forms of pulmonary tuberculosis [3,4]. Moreover, prior exposure of individual to environmental mycobacteria and organisms sharing antigenic epitopes results in recall of immune memory response to BCG administration [3]. After almost 12 decades of research, we still do not have a reliable diagnostic test for TB that can be used in primary health care centers with definitive results.

In 1890, Robert Koch introduced boiled, crude extract of tubercle bacilli in glycerin (referred as “old tuberculin”) as a potential vaccine material against tuberculosis infection [5-7]. Although Koch’s old tuberculin could not be used as therapy because of its toxicity, impurity and inadequate standardization; the concept of tuberculin was instrumental in laying the foundation of the modern TST [8]. TST, first introduced by Von Pirquet in 1909 [6] has been in use as a standard method for diagnosing TB infection almost over the last six decades [8,9]. It is based on measuring the extent of induration formed because of delayed type hypersensitivity reaction elicited by mycobacterial antigens present in PPD.

In addition to its role in detecting mycobacterial infection, TST has also been used as a standard tool to estimate the prevalence of LTBI [8]. The role of PPD in serodiagnosis of TB, with sensitivity as high as 92%, was reported in Warao and Creole populations [10]. Several studies reported the use of PPD in serodiagnosis of tuberculosis infection with high sensitivity [11,12]. PPD has also been used as a standard control in immunological assays [13]. It is reported that PPD improves the sensitivity of interferon gamma release assay (IGRA). IGRA uses early secretory antigenic target-6 (ESAT-6) and culture filtrate antigen EsxB (CFP10) antigens present in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis but not in BCG. This can enable differentiation of TB-infected and BCG vaccinated individuals [14,15]. However, Yassin et al. reported that sensitivity of IGRA can be compromised in children with severe malnutrition and HIV co-infection. Concomitant use of TST, IGRA and interferon gamma induced protein 10 (IP-10) in children staying in contact with smear-positive adults has shown higher number of children as positive [16]. In addition, IGRAs suffer from limitations including higher cost, variable sensitivity, poor reproducibility, limited interpretive criteria and unknown prognostic value [17]. Despite its important applications, PPD is not considered as a reliable material. This is due to high rates of false positive results, inability to distinguish between tuberculous and non-tuberculous mycobacteria or individuals vaccinated with BCG [18]. This can be attributed to immune response elicited by antigens from BCG or environmental bacteria sharing antigenic epitopes [19,20]. Earlier studies by Borsuk et al. identified molecular chaperone DnaK (DnaK), molecular chaperone GroEL (GroEL2), elongation factor 2 (EF-Tu), cell surface lipoprotein Mpt83 (Mpt83) and acyl carrier protein as abundant proteins common to M. bovis and M. avium PPDs [21]. Moreover, discrepancy of results has been observed between different PPD preparations [22,23]. Currently available PPD preparations used on human subjects include PPD-S2 [6], PPD-RT23 [24], PPD IC-65 [9,13] and PPD-CT68 [25].

Knowledge about the constituents of PPD could allow the researchers to effectively work on PPD associated diagnostic complications. Earlier studies employed gel electrophoresis to identify constituents of PPD [26]. Kuwabara and Tsumita in 1974 first attempted to identify and characterize the components of PPD [27]. An analysis which employed gel electrophoresis for characterization of PPD antigens in whole cell lysate of M. bovis BCG resulted in four protein bands corresponding to PPD [28]. Kitaura et al. could distinctly identify only two ribosomal proteins L7 and L12 in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis PPDs in gel electrophoresis [29]. With the advent of high resolution mass spectrometry, it is now possible to identify proteins from complex peptide mixtures. Borsuk et al. identified 171 proteins in an LC-MS/MS analysis of Brazilian and UK bovine and avium PPDs [19]. Cho et al. recently identified 240 proteins in PPD-S2 [26]. PPD-CT68, which is another standard reagent used for TST, has not been analyzed thus far. In the present report, we have analyzed and described the proteome profile of PPD-CT68 using high resolution mass spectrometry and compared it with that of other PPDs derived from M. tuberculosis, M. avium and M. Bovis. PPD-CT68 examined here was developed by Landi in 1963 from “Johnston” strain of M. tuberculosis var. hominis[30].

Results and discussion

Identification of proteins present in PPD-CT68 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis

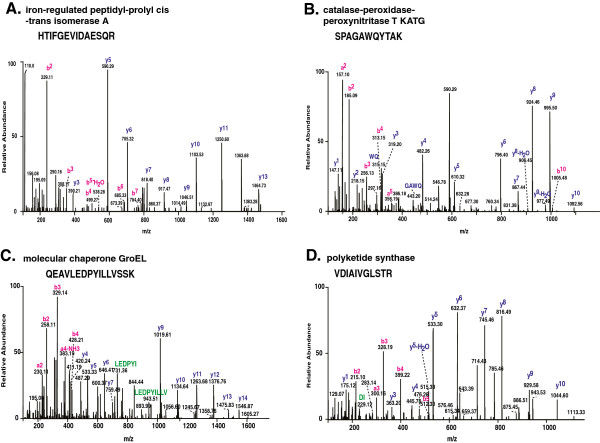

We carried out a proteomic profiling of PPD-CT68 prepared from M. tuberculosis culture in a protein-free medium using high resolution Fourier transform mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry-derived data was searched using Sequest algorithm embedded in the Proteome Discoverer software against a protein database of M. tuberculosis from NCBI RefSeq. Search of 5,205 MS/MS spectra resulted in 1,146 peptide-spectrum matches, which corresponded to 695 unique peptides. The list of peptides identified in this study is provided in Additional file 1: Table S1. Representative MS/MS spectra are provided in Figure 1. Based on these 695 unique peptides, we identified 265 proteins (Additional file 2: Table S2) of M. tuberculosis in PPD-CT68.

Figure 1.

MS/MS spectra of peptides from some of the M. tuberculosis PPD-CT68 proteins identified in this study (A) iron-regulated peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A (B) catalase-peroxidase peroxynitritase T KatG (C) molecular chaperone GroEL (D) polyketide synthase.

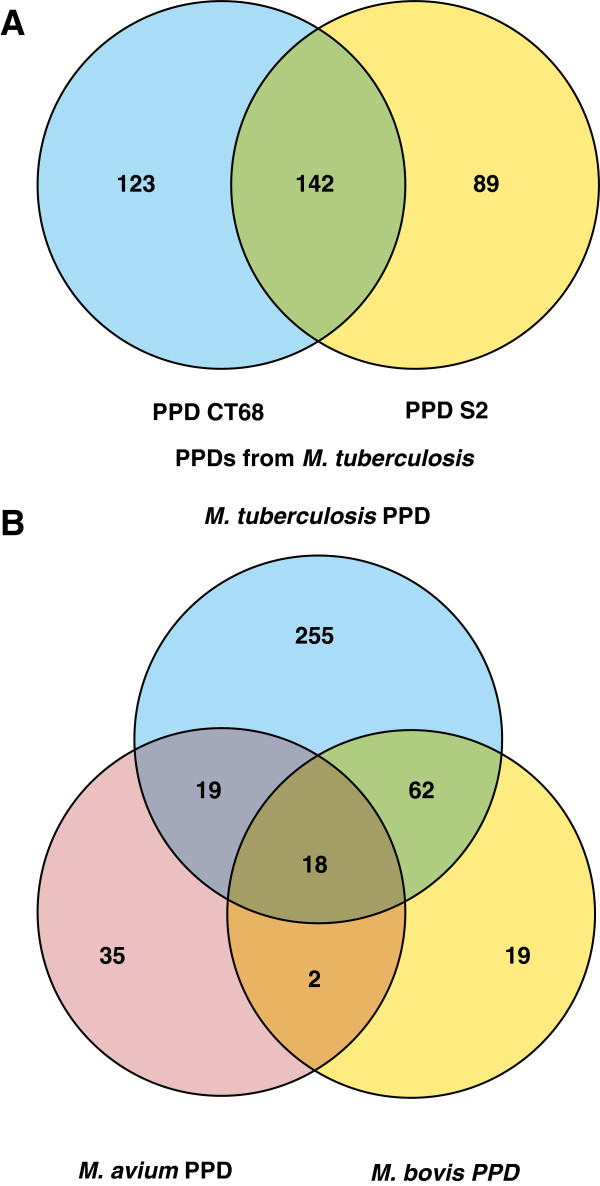

Cho and colleagues [26] recently reported the identification of 240 proteins from PPD-S2, which is the standard for TST, as recommended by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Out of 240 proteins listed, 231 are non-redundant. We compared proteomic results obtained in our study with proteins identified from PPD-S2 (Figure 2A). Out of the 265 proteins identified from PPD-CT68, 142 proteins were shared with PPD-S2, whereas, 123 and 89 proteins were exclusively identified from PPD-CT68 and PPD-S2, respectively. Altogether, 354 proteins of M. tuberculosis PPD have been identified.

Figure 2.

Overlap of proteins identified among PPD-CT68 and PPD-S2 (A) Proteins identified among M. tuberculosis PPD, M. avium PPD and M. bovis PPD (B).

For further understanding of protein profiles of various PPD preparations, we compared the PPD derived from M. tuberculosis (PPD-CT68 and PPD-S2) with PPDs of M. bovis and M. avium[19] (Figure 2B). Out of 354 proteins from M. tuberculosis PPDs, 37 proteins were found common with M. avium PPD and 80 were common with M. bovis PPD. We also found that 18 proteins were common in PPDs obtained from M. tuberculosis, M. bovis and M. avium. When compared to PPDs from M. tuberculosis, 35 and 19 proteins were exclusively found in M. avium and M. bovis PPDs respectively. It is also interesting to note that 255 proteins were exclusively identified in PPDs from M. tuberculosis.

Functional analysis of proteins common among all PPDs

We carried out functional classification of proteins identified in M. tuberculosis (PPD-CT68 and PPD-S2), which are also present in M. avium and M. bovis. Most of the proteins were implicated in causing infection and protecting the pathogen against various metabolic stresses. Five of eighteen proteins- secreted antigen 85A (FbpA), thiol peroxidase (Tpx), bacterioferritin (BfrA), thioredoxin (TrxC) and lipoprotein LprG (LprG) - offer protection against oxidative and nitrosative stress. On the other hand, co-chaperonin GroES (GroES), DnaK, serine protease PepA (PepA), alanine and proline rich secreted protein Apa (Apa) and hypothetical protein Mpt64 are involved in causing infection. Detailed functional classification of each protein is given in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Functional classification of proteins common in all PPDs

| Gene symbol | Description | Function | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

AcpP |

Acyl carrier protein |

It shuttles the intermediates between the enzymes of type II fatty acid synthase system |

[31] |

| 2 |

FbpA |

Secreted antigen 85-A |

It participates in cell wall biosynthesis, and interacts with the host macrophage as fibronectin-binding protein. It is also involved in establishment and maintenance of a persistent tuberculosis infection |

[32,33] |

| 3 |

GroES |

Co-chaperonin |

It is a dominant immunogenic protein |

[34] |

| 4 |

DnaK |

Molecular chaperone |

It is highly antigenic and act as co-repressors for heat shock protein transcriptional repressor (hspR) |

[35] |

| 5 |

Tpx |

Thiol peroxidase |

It protects M. tuberculosis against oxidative and nitrosative stress |

[36] |

| 6 |

RpiL |

50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 |

It is involved in interaction with translation factors |

[37] |

| 7 |

BfrA |

Bacterioferritin |

It is an intracellular iron storage protein, which protects Mycobacterium from oxidative stress mediated by excess iron |

[38] |

| 8 |

SahH |

S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase |

It is a ubiquitous enzyme that plays a central role in methylation-based processes by maintaining the intracellular balance between S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) and S-adenosylmethionine |

[39] |

| 9 |

TrxC |

Thioredoxin |

It is involved in redox homeostasis and uses it to protect the pathoen against the oxidative intermediates generated by the macrophages |

[40] |

| 10 |

FixB |

Electron transfer flavoprotein subunit alpha |

It is electron transfer flavoprotein subunit alpha, in some bacteria it functions as nitrogen fixing agent but its function in M .tuberculosis is not clear |

[41] |

| 11 |

PepA |

Serine protease |

It is a serine protease associated with cell membrane, which stimulates peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy PPD donors to proliferate and secrete gamma interferon |

[42] |

| 12 |

Wag31 |

Hypothetical protein |

It is a cell division initiation protein involved in regulation of genes including virulence factors and antigens |

[43] |

| 13 |

Mpt64 |

Hypothetical protein |

It is an immunogenic protein which elicits delayed type hypersensitivity skin response |

[44] |

| 14 |

Apa |

Alanine and proline rich secreted protein |

It is a cell surface glycoprotein which binds to host lectins and cheat the innate immune system |

[45] |

| 15 |

LprG |

Lipoprotein LprG |

It plays a role in M. tuberculosis infection by inducing increased suppression of the immune response due to elevated nitric oxide production |

[46] |

| 16 |

Rv1893 |

Hypothetical protein |

Function unknown |

[47] |

| 17 |

Rv1855c |

Oxidoreductase |

Probable monooxygenase |

[48] |

| 18 | Gap | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | It has glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity | [49] |

Bioinformatics analysis of PPD-CT68 proteins showing homology to lung infecting bacteria

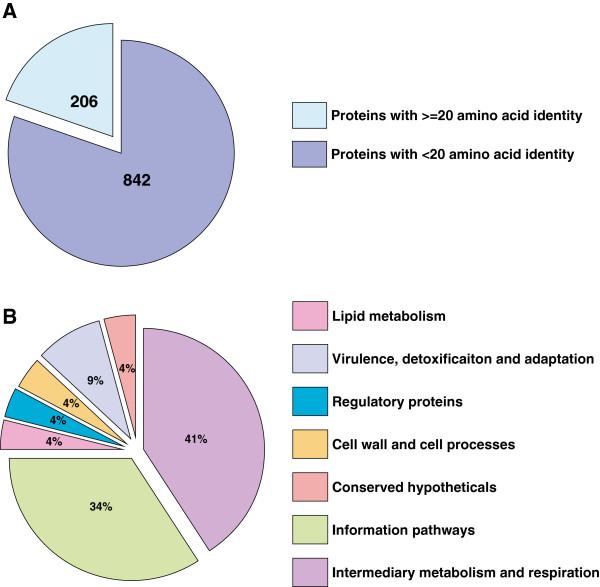

Raman et al. performed a comprehensive analysis on M. tuberculosis genes homologous to 228 different pathogenic bacteria [50]. We further analyzed 265 proteins represented in PPD-CT68 against the proteins encoded by 24 lung infecting bacteria selected from the list of 228 pathogens. Protein BLAST was performed to locate regions of PPD-CT68 proteins sharing 10 or more identical amino acid long regions with bacterial proteins. In all, 3,446 peptides from 24 pathogens corresponding to 1,048 proteins showed 10 or more amino acid identity with 117 proteins from PPD-CT68 (Additional file 3: Table S3a and S3b). Since, a peptide of 20 or more amino acid residues can be a potential epitope, we further shortlisted the proteins reflecting identity in a continuous stretch of 20 or more amino acids (Additional file 3: Table S3c). Two hundred and six out of 1,048 bacterial proteins showed identity with 47 PPD-CT68 proteins. (Figure 3A). Functional analysis of 47 mycobacterial proteins sharing identical regions revealed that 41% proteins are associated with intermediary metabolism and respiration, 34% with information pathways, 9% with virulence and detoxification, 4% with cell wall and cell processes, 4% with lipid metabolism and 4% with regulatory proteins (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Pie chart representing lung infecting bacterial proteins with <20 amino acid long peptides and ≥20 amino acid long peptides identical to PPD-CT68 proteins (A). Functional classification of 47 PPD-CT68 proteins showing identity of 20 or more amino acids in 24 lung infection associated bacterial proteins (B).

To further study the role of these 47 proteins in DTH and serodiagnosis, we compared our data with immunoproteome of M. tuberculosis reported by Velayudhan et al., which included 484 mycobacterial proteins recognized by human sera collected from worldwide TB suspects [51]. Thirteen proteins - DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta; DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit alpha; GroEL; 30S ribosomal protein S1; fumarate hydratase; elongation factor G; DnaK; aconitate hydratase; isocitrate dehydrogenase; S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase; malate synthase G; D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase; and enoyl-CoA hydratase - were recognized by antibodies in serum. Out of these 13 proteins, only seven (isocitrate dehydrogenase; malate synthase G; succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit alpha; malate dehydrogenase; succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit beta; aconitate hydratase; and type II citrate synthase) were listed in immunoproteome and were identified in our mass spectrometry analysis of PPD-CT68 [51]. These proteins are associated with a host immune response in cases with active tuberculosis.

PPD proteins as candidate biomarkers

Available knowledge of the M. tuberculosis genes provides us the advantage to express and synthesize recombinant purified antigens, which gives us the opportunity to test new biomarkers for TB infection. These antigens can be used to detect the antibodies in the serum and have a potential to improve diagnosis. Several studies have explored the use of the recombinantly expressed antigens and evaluated their immunodiagnostic potential. An updated systematic review on the diagnostic accuracy of commercial serological tests for pulmonary and extra pulmonary tuberculosis for relevant studies was updated in May 2010 and WHO has performed a bivariate meta-analysis that jointly modeled both test sensitivity and specificity (http://www.who.int/tb/laboratory/policy_statements/en/index.html). It has been concluded that the commercially available serological tests provide inconsistent and imprecise findings and the sensitivity and specificity of the tests were highly variable. Our approach presented in this study, has not only identified a large number of proteins unique to M. tuberculosis, but in parallel provided the information on the coverage. The higher the coverage, higher is the abundance of the protein in the PPD sample analyzed. Our results are correlating with earlier publications and many of the proteins identified in the PPD of M. tuberculosis, have already been analyzed for their potential as a diagnostic markers. Some of the hits we have found are GroES [52,53], GroEL [54,55], protein EsxB (EsxB) [56] heat shock protein HspX (HspX) [57], hypothetical protein (TB15.3), hypothetical protien (TB16.3) [58], 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 (RplL) [59], hypothetical protein (EsxA) [60], immunogenic protein Mpt63 (Mpt63) [61], Mpt64 [62], ESAT-6 like protein EsxJ (EsxJ), and ESAT-6 like protein EsxO (EsxO) [63]. Based on these observations, many more M. tuberculosis PPD can be analyzed and the abundant antigens be evaluated for their potential as diagnostics biomarkers.

Clinical applications of the study

Based on our findings, out of 265 proteins identified in PPD-CT68, 142 proteins were found common between PPD-CT68 and PPD-S2. The common proteins can further be evaluated for their potential as skin test antigens. Proteins identified in our analysis, which are absent in M. avium and M. bovis and do not show any significant identity with proteins from lung infecting bacteria can be shortlisted for developing various immunological assays to identify M. tuberculosis, on the basis of their seroreactivity and abundance. For example, Rv2346, Rv0379 and Rv1388 were found to be absent in PPD M. bovis and PPD M. avium and possessed least identity with proteins from lung infecting pathogens. As discussed earlier, one of the major issues with the use of PPD as a skin test antigen is false positive results for the individuals with BCG vaccination. Use of antigens absent in M. bovis may help overcoming that. Global profiling of antigens in PPD may help to identify M. tuberculosis-specific antigens, which are not present in BCG. These antigens will be useful in differentiating infected from vaccinated individuals. PPD can be prepared from M. tuberculosis, M. avium and M. bovis, so if we can use antigen specific to every strain to elicit the test response we can diagnose the species of Mycobacteria with a simple skin test. Subset of antigens that is mainly responsible for activating the immune response can be used in adjunction with BCG or for booster doses to enhance immune response. By knowing the antigens involved in the test response, we can use minimal essential amount of PPD for TST. Use of specific antigens in TST will make it more specific and will reduce the false positive results due to antigen cross reaction.

Conclusions

Despite the identification of almost a dozen antigens for developing next generation PPD, it is challenging to replace the classical PPD preparation. ESAT-6, Mpt64, recombinant antigen (DPPD), CFP10, recombinant truncated 38 kDa protein (TPA38), DnaK, GroEL, RplL are currently under evaluation as next generation PPD candidates [9,29,62,64-72]. PPD is a crude extract obtained after several steps of filtration, purification, and precipitation with trichloroacetic acid [30]. Enough knowledge on PPD composition and contribution of individual antigens in TST would give a better insight to understand the molecular mechanism behind it and will also allow the researchers to select a combination of proteins specific to M. tuberculosis. Our analysis further revealed mycobacterial proteins in PPD-CT68 sharing identical amino acid sequence with lung infecting bacteria. Detailed epitopic analysis of these proteins may help the researchers to understand the mechanism behind cross reactivity in TST.

Mass Spectrometry is an efficient tool for proteomic analysis due to its high mass accuracy, sensitivity and ability to deal with complex sample mixtures. Here, in this study we used a high resolution Fourier transform mass spectrometer for LC-MS/MS analysis of PPD-CT68. Many of the proteins identified in the PPD of M. tuberculosis, have already been analyzed for their potential as diagnostic markers. The complete protein profile of PPD-CT68 uncovered from this study can be used to analyze immune response and antibody production pattern of body against different PPD antigens.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository [73] with the dataset identifier PXD000377.

Methods

Trypsin digestion

PPD-CT68 (100 μg protein) was subjected to in-solution digestion using trypsin. Reduction and alkylation were carried out using 5 mM dithiothreitol (60°C for 45 min) and 20 mM iodoacetamide (RT for 10 min), respectively. Overnight digestion was carried out using trypsin with an enzyme: substrate ratio of 1:20 at 37°C [74]. The digest was then purified using sep-pak C18 columns (WAT051910, Waters Corporation, MA) [75] and the eluates were lyophilized at -52°C (Operon, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) and stored at -80°C until LC-MS/MS analysis.

Mass spectrometry

We have carried out the LC-MS/MS analysis on an LTQ-Orbitrap Velos ETD mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) interfaced with an Agilent 1100 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Trypsin digested PPD peptides were analyzed on a reversed phase liquid chromatography. The RP-LC system equipped with a pre-column (2 cm, 5 μ – 100A°), analytical column (10 cm, 5 μ – 100A°) made with magic AQ C18 material (PM5/61100/00; Bruker-Michrom Inc., Auburn, CA) packed in-house. Further, the peptides were sprayed using an electro-spray emitter tip 8 μ (New Objective, Woburn, MA) fixed to a nanospray ionization source. The peptides were loaded on the pre-column using 97% solvent A (0.1% formic acid (aq) and resolved on the analytical column using a gradient of 10-30% solvent B (90% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) for 60 min at a constant flow rate of 0.35 μl/min. The spray voltage and heated capillary temperature were set to 2.0 kV and 220°C, respectively. The data acquisition was performed in a data dependent manner. From each MS survey scan, 10 most intense precursor ions were selected for fragmentation. MS and MS/MS scans were acquired in an Orbitrap mass analyzer and the peptides were fragmented by higher energy collision dissociation with normalized collision energy of 39%. MS scans were acquired at a resolution of 60,000 at 400 m/z, while MS/MS scans were acquired at a resolution of 15,000. The automatic gain control for full FT MS was set to 0.5 million ions and for FT MS/MS was set to 0.1 million ions with maximum time of accumulation of 750 ms and 100 ms, respectively. The raw data obtained was submitted to ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org).

Data analysis

We searched the MS/MS data using Sequest search algorithm on Proteome Discoverer (version 1.3.0.339, Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany), against protein database of M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain downloaded from NCBI RefSeq (updated December 29, 2011). The search parameters are: a) precursor mass range between 350 to 8000 Da; b) minimum peak count was set to 5; c) signal to noise threshold set to 1.5; d) trypsin was used as a proteolytic enzyme allowing up to one missed cleavage; e) precursor mass tolerance of 20 ppm and fragment tolerance of 0.1 Da; f) oxidation of methionine as variable modification and carbamidomethylation of cysteine as fixed modification; and g) 1% false discovery rate (FDR).

Abbreviations

AcpP: Acyl carrier protein; Apa: Alanine and proline rich protein; BCG: Bacillus Calmette-Guerin; BfrA: Bacterioferritin; BLAST: Basic Local Alignment Search Tool; CFP10: Culture filtrate antigen EsxB; EF-Tu: Elongation factor 2; EsxJ: ESAT-6 like protein EsxJ; EsxO: ESAT-6 like protein EsxO; ESAT-6: Early secretory antigenic target-6; FbpA: Secreted antigen 85A; GroES: Co-chaperonin GroES; HspX: Heat shock protein HspX; IGRA: Interferon gamma release assay; IP-10: Interferon gamma induced protein 10; LC-MS/MS: Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry; LprG: Lipoprotein LprG; LTBI: Latent tuberculosis infection; Mpt83: Cell surface lipoprotein Mpt83; PepA: Serine protease PepA; PPD-CT68: Purified protein derivative-Connaught tuberculin 68; RpiL: 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12; SahH: S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase; Tpx: Thiol peroxidase; TrxC: Thioredoxin; TPA38: Truncated 38kDa protein; TST: Tuberculin skin test.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

JN, TSKP and AP conceived the study and designed the experiments; SK, NRS, GJS and HCH carried out the experiments; TSKP, HCH, RV, AKM and JS analyzed the data; TSKP, RV and VNP wrote the manuscript; JN, AG, AC and VPM provided critical comments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

List of peptides identified from M. tuberculosis PPD (CT68).

List of proteins identified from M. tuberculosis PPD (CT68).

List of Mycobacterium tuberculosis PPD-CT68 peptides with 10 or more amino acid identity with 24 lung infecting bacteria. Table S3b. List of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins corresponding to the peptides with 10 or more amino acid identity with 24 lung infecting bacteria. Table S3c. List of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins with sequence identity of ≥ 20 amino acid identity with 24 lung infecting bacteria.

Contributor Information

Thottethodi Subrahmanya Keshava Prasad, Email: keshav@ibioinformatics.org.

Renu Verma, Email: renuverma@ibioinformatics.org.

Satish Kumar, Email: satishkumar9049@gmail.com.

Raja Sekhar Nirujogi, Email: raja@ibioinformatics.org.

Gajanan J Sathe, Email: gajanan@ibioinformatics.org.

Anil K Madugundu, Email: anil@ibioinformatics.org.

Jyoti Sharma, Email: jyoti@ibioinformatics.org.

Vinuth N Puttamallesh, Email: vinuth@ibioinformatics.org.

Anjali Ganjiwale, Email: anjali.dike@gmail.com.

Vithal P Myneedu, Email: vpm_myn@yahoo.com.

Aditi Chatterjee, Email: aditi@ibioinformatics.org.

Akhilesh Pandey, Email: pandey@jhmi.edu.

HC Harsha, Email: harsha@ibioinformatics.or.

Jayasuryan Narayana, Email: jayasuryanmn@gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

Thottethodi Subrahmanya Keshava Prasad is the recipient of the DST-IDP research grant “Development of epitope based diagnostic gadget for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Indian population” from the Department of Science Technology, Government of India. H.C. Harsha is a Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance Early Career Fellow. Renu Verma is a recipient of Junior Research Fellowship from University Grants Commission (UGC), Government of India. Gajanan J. Sathe is a recipient of a Junior Research Fellowship from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India. Anil K. Madugundu is a recipient of Junior Research Fellowship from Department of Biotechnology-Bioinformatics National Certification (DBT-BINC). Jyoti Sharma is a recipient of a Senior Research Fellowship from the CSIR, New Delhi, India. This study was supported in part by an NIH roadmap grant for Technology Centers of Networks and Pathways (U54RR020839). The data deposition to the ProteomeXchange Consortium was supported by PRIDE Team, EBI.

References

- Pineiro R. et al. Tuberculin skin test in bacille Calmette-Guerin-vaccinated children: how should we interpret the results? Eur J Pediatr. 2012;10(11):1625–32. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1783-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000;10(RR-6):1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt L. et al. Failure of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine: some species of environmental mycobacteria block multiplication of BCG and induction of protective immunity to tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2002;10(2):672–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.672-678.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine PE. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet. 1995;10(8986):1339–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingadia D, Novelli V. The tuberculin skin test: a hundred, not out? Arch Dis Child. 2008;10(3):189–90. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.129585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Holzman RS. Evolution and current use of the tuberculin test. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;10(3):365–70. doi: 10.1086/338149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke DS. Of postulates and peccadilloes: Robert Koch and vaccine (tuberculin) therapy for tuberculosis. Vaccine. 1993;10(8):795–804. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(93)90354-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Absi A. et al. The decline of tuberculosis in Yemen: evaluation based on two nationwide tuberculin surveys. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;10(9):1100–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Kruh-Garcia NA, Dobos KM. Purified protein derivatives of tuberculin - past, present, and future. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;10(3):273–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.01002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo Z. et al. Comparison of serological responses in two different populations with pulmonary tuberculosis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;10(7):661–7. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762008000700006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amicosante M. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a multi-antigen ELISA test for the serological diagnosis of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;10(8):736–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang PH, Kim JS. PPD-specific IgG and IgG subclasses in the sera of pulmonary tuberculosis patients. J Korean Med Sci. 1993;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1993.8.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavri HR. et al. Prospective Comparison of Two Brands of Tuberculin Skin Tests and Quantiferon-TB Gold in-tube Assay Performances for Tuberculosis Infection in Hospitalized Children. Maedica (Buchar) 2010;10(4):271–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddle BM. et al. Use of ESAT-6 in the interferon-gamma test for diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis following skin testing. Vet Microbiol. 2001;10(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(00)00375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddle BM. et al. Differentiation between Mycobacterium bovis BCG-vaccinated and M. bovis-infected cattle by using recombinant mycobacterial antigens. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;10(1):1–5. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.1.1-5.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassin M. et al. Added value of TST, IGRAS and IP-10 to identify children with TB infection. Eur Respir J. 2012;10(3):644–648. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00012212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera V. et al. Clinical application and limitations of interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;10(8):1031–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner RE, Schein MF, Bass JB Jr. The tuberculin skin test. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;10(6):968–75. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.6.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsuk S. et al. Identification of proteins from tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) by LC-MS/MS. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2009;10(6):423–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harboe M. Antigens of PPD, old tuberculin, and autoclaved Mycobacterium bovis BCG studied by crossed immunoelectrophoresis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;10(1):80–7. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.124.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan SK. et al. Induced folding by chiral nonplanar aromatics. J Org Chem. 2009;10(18):7023–33. doi: 10.1021/jo9013047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp ME, Schultz AW Jr, Davis JC. Discordance between tuberculin skin test results with two commercial purified protein derivative preparations. J Infect Dis. 1994;10(5):1174–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifson AR. et al. Discrepancies in tuberculin skin test results with two commercial products in a population of intravenous drug users. J Infect Dis. 1993;10(4):1048–51. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.4.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guld J. et al. Standardization of a new batch of purified tuberculin (PPD) intended for international use. Bull World Health Organ. 1958;10(5):845–951. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussetti P. et al. Tuberculin reactivity in the elderly. Comparison of PPD-RT23 and PPD-CT68. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1996;10(2):80–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YS. et al. Deciphering the proteome of the in vivo diagnostic reagent “purified protein derivative” from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proteomics. 2012;10(7):979–91. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara S, Tsumita T. Letter: Primary structure of tuberculin-active protein from tubercule bacilli. Jpn J Exp Med. 1974;10(1):129–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardarov SS. et al. Characterization of PPD protein antigens in whole cell lysates of Mycobacterium bovis BCG. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;10(1–2):89–93. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90037-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaura H, Kinomoto M, Yamada T. Ribosomal protein L7 included in tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) is a major heat-resistant protein inducing strong delayed-type hypersensitivity. Scand J Immunol. 1999;10(6):580–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi S. Preparation, Purification, and Stability of Tuberculin. Appl Microbiol. 1963;10:408–12. doi: 10.1128/am.11.5.408-412.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong HC. et al. The solution structure of acyl carrier protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;10(18):15874–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elamin AA. et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ag85A is a novel diacylglycerol acyltransferase involved in lipid body formation. Mol Microbiol. 2011;10(6):1577–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero IC. et al. Identification of promoter-binding proteins of the fbp A and C genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2010;10(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb AJ, Frothingham R. The GroES antigens of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Vet Microbiol. 1999;10(1):31–5. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(99)00019-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Gupta T. B. Bandyopadhyay, and S.K. Das Gupta, Modulation of DNA-binding activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis HspR by chaperones. Microbiology. 2008;10(Pt 2):484–90. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho BS. et al. Functional and structural characterization of a thiol peroxidase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Biol. 2006;10(5):850–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudkov AT. The L7/L12 ribosomal domain of the ribosome: structural and functional studies. FEBS Lett. 1997;10(3):253–6. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00361-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PV. et al. Iron storage proteins are essential for the survival and pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in THP-1 macrophages and the guinea pig model of infection. J Bacteriol. 2012;10(3):567–75. doi: 10.1128/JB.05553-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MC. et al. Crystal structures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase in ternary complex with substrate and inhibitors. Protein Sci. 2008;10(12):2134–44. doi: 10.1110/ps.038125.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall G. et al. Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis thioredoxin C. Acta Crystallogr D: Biol Crystallogr. 2006;10(Pt 12):1453–7. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906038212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MH, Saier MH Jr. Phylogenetic characterization of the ubiquitous electron transfer flavoprotein families ETF-alpha and ETF-beta. Res Microbiol. 1995;10(5):397–404. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)80285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert AM. et al. DNA polymorphisms in the pepA and PPE18 genes among clinical strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for vaccine efficacy. Infect Immun. 2007;10(12):5798–805. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00335-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau Bonilla D, Dahl JL. The wag31 gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is positively regulated by the stringent response. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;10(2):153–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisbrecht BV. et al. Design and optimization of a recombinant system for large-scale production of the MPT64 antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;10(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragas A. et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell-surface glycoprotein apa as a potential adhesin to colonize target cells via the innate immune system pulmonary C-type lectin surfactant protein A. J Biol Chem. 2007;10(8):5133–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610183200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovav AH. et al. Aggravated infection in mice co-administered with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the 27-kDa lipoprotein. Microbes Infect. 2006;10(7):1750–7. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST. et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;10(6685):537–44. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S. et al. Comprehensive proteomic profiling of the membrane constituents of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;10(12):1284–96. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300060-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe LM. et al. Proteomic definition of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Proteome Res. 2010;10(11):5816–26. doi: 10.1021/pr1005873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman K, Yeturu K, Chandra N. targetTB: a target identification pipeline for Mycobacterium tuberculosis through an interactome, reactome and genome-scale structural analysis. BMC Syst Biol. 2008;10:109. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-2-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunnath-Velayudhan S. et al. Dynamic antibody responses to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;10(33):14703–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattorini L. et al. Recombinant GroES in combination with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides protects mice against Mycobacterium avium infection. J Med Microbiol. 2002;10(12):1071–9. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-12-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain R. et al. Immune profiling of leprosy and tuberculosis patients to 15-mer peptides of Mycobacterium leprae and M. tuberculosis GroES in a BCG vaccinated area: implications for development of vaccine and diagnostic reagents. Immunology. 2004;10(4):462–71. doi: 10.1111/j.0019-2805.2004.01839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pais TF. et al. Analysis of T cells recruited during delayed-type hypersensitivity to purified protein derivative (PPD) versus challenge with tuberculosis infection. Immunology. 1998;10(1):69–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos JA, Giambiagi-Demarval M, Castro AC. Expression of heat-shock proteins in Streptococcus pyogenes and their immunoreactivity with sera from patients with streptococcal diseases. J Med Microbiol. 1998;10(8):711–5. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-8-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garufi G, Butler E, Missiakas D. ESAT-6-like protein secretion in Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2008;10(21):7004–11. doi: 10.1128/JB.00458-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geluk A. et al. T-cell recognition of the HspX protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis correlates with latent M. tuberculosis infection but not with M. bovis BCG vaccination. Infect Immun. 2007;10(6):2914–21. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01990-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weldingh K. et al. Assessing the serodiagnostic potential of 35 Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins and identification of four novel serological antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;10(1):57–65. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.57-65.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahk YY. et al. Antigens secreted from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: identification by proteomics approach and test for diagnostic marker. Proteomics. 2004;10(11):3299–307. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khera A. et al. Elicitation of efficient, protective immune responses by using DNA vaccines against tuberculosis. Vaccine. 2005;10(48–49):5655–65. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manca C. et al. Molecular cloning, purification, and serological characterization of MPT63, a novel antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1997;10(1):16–23. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.16-23.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhay MJ, Oettinger T, Andersen P. Delayed-type hypersensitivity responses to ESAT-6 and MPT64 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the guinea pig. Infect Immun. 1998;10(7):3454–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3454-3456.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XY. et al. Comparative proteome analysis of culture supernatant proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and H37Ra. Microbes Infect. 2003;10(10):851–6. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. et al. Three protein cocktails mediate delayed-type hypersensitivity responses indistinguishable from that elicited by purified protein derivative in the guinea pig model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2011;10(2):716–23. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00486-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. et al. Recombinant early secreted antigen target 6 protein as a skin test antigen for the specific detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;10(1):81–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend SM. et al. Double-blind randomized Phase I study comparing rdESAT-6 to tuberculin as skin test reagent in the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2008;10(3):249–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. et al. Expression and purification of immunologically reactive DPPD, a recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis skin test antigen, using Mycobacterium smegmatis and Escherichia coli host cells. Can J Microbiol. 2004;10(2):97–105. doi: 10.1139/w03-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock JM. et al. Specific delayed-type hypersensitivity responses to ESAT-6 identify tuberculosis-infected cattle. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;10(5):1856–60. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.5.1856-1860.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Neto A. et al. Evaluation of DPPD, a single recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein as an alternative antigen for the Mantoux test. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2001;10(5–6):353–8. doi: 10.1054/tube.2001.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Pinxteren LA. et al. Diagnosis of tuberculosis based on the two specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP10. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;10(2):155–60. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.2.155-160.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangeli R. et al. MTSA-10, the product of the Rv3874 gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, elicits tuberculosis-specific, delayed-type hypersensitivity in guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 2000;10(2):990–3. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.2.990-993.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oettinger T. et al. Mapping of the delayed-type hypersensitivity-inducing epitope of secreted protein MPT64 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;10(12):4613–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4613-4618.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaino JA. et al. The Proteomics Identifications database: 2010 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;10(Database issue):D736–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harsha HC, Molina H, Pandey A. Quantitative proteomics using stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture. Nat Protoc. 2008;10(3):505–16. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappsilber J, Mann M, Ishihama Y. Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat Protoc. 2007;10(8):1896–906. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of peptides identified from M. tuberculosis PPD (CT68).

List of proteins identified from M. tuberculosis PPD (CT68).

List of Mycobacterium tuberculosis PPD-CT68 peptides with 10 or more amino acid identity with 24 lung infecting bacteria. Table S3b. List of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins corresponding to the peptides with 10 or more amino acid identity with 24 lung infecting bacteria. Table S3c. List of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins with sequence identity of ≥ 20 amino acid identity with 24 lung infecting bacteria.

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository [73] with the dataset identifier PXD000377.