Abstract

Ocular melanomas comprise uveal and conjunctival sub-types, which are very different from each other. A large majority of uveal melanomas involve the choroid, with less than 10% being confined to the ciliary body and iris. They tend to metastasize haematogenously, almost always involving the liver. Therapeutic methods include various forms of radiotherapy, surgical resection and phototherapy, which are often used in combination. Conjunctival melanomas show many similarities to their cutaneous counterparts, often metastasizing by lymphatic spread. Treatment consists of excision of invasive melanoma with adjunctive radiotherapy and/or cryotherapy and topical chemotherapy for intra-epithelial disease. The management of patients with ocular melanomas demands a good understanding of the pathology of these tumours. Pathological examination of the tumour indicates the prognosis and hence the need for further investigation and treatment. The scope of the pathologist is enhanced thanks to advances in molecular biology.

Keywords: Melanoma, Eye, Uvea, Conjunctiva, Pathology

Introduction

Ocular melanomas are rare, especially in countries such as Saudi Arabia. Nevertheless, it behoves clinicians to have some knowledge of this disease so that when they encounter individuals with this condition they can offer the standard of care that these patients deserve. Even though such patients may be referred to an ocular oncology centre overseas, the success of their management depends greatly on the care that is provided at the home hospital, which would include diagnosis, counselling and long-term follow-up.

As with any disease, a good understanding of the underlying pathology is fundamental to patient care. There are many excellent sources of information on the pathology of ocular melanomas; however, some articles have become outdated because of rapid advances that have occurred in recent years, and other texts are not easily accessible.

The aims of this article are to provide a succinct yet practical overview of the pathology of ocular melanomas, with a guide to the more detailed literature on the subject. It is hoped that this review will be relevant not only to pathologists but also to ophthalmologists and oncologists.

Uveal melanoma

Introduction

Uveal melanomas account for approximately 98% of all ocular melanomas. More than 90% of intraocular melanomas arise in the choroid, with about 3–4% developing in the iris and the remainder in the ciliary body.1

In Caucasians, uveal melanomas have an incidence of approximately 7 per million per year.2 Presentation peaks at the age of sixty years and is rare before adulthood. Males and females are affected in equal numbers, although iris melanomas tend to be slightly more common in women whereas choroidal melanomas are more common in men.1

Risk factors for uveal melanoma include: light skin, blue eyes, tendency to cutaneous naevi, congenital ocular melanocytosis, uveal melanocytoma and neurofibromatosis. The role of sunlight is uncertain but it is noteworthy that most iris melanomas occur inferiorly, where there is less protection from the upper eyelid.

Histology

According to the modified Callendar classification, uveal melanoma cytomorphology is categorized as: spindle; epithelioid; and mixed. Spindle cells are long and narrow, with large nuclei and nucleoli.3 They were previously called ‘spindle-B’ cells to differentiate them from Spindle A cells with furrowed nuclei, which are now considered to be benign. Epithelioid cells are larger, with eosinophilic cytoplasm and can be poorly cohesive (Fig. 1a). Rarely, the tumour is entirely necrotic so that the cytomorphology is unclassifiable. Immunohistochemistry staining of proteins such as Heat Shock Protein 27 (HSP-27) may be used for prognostic purposes (Fig. 1b).4 Conventionally, mitoses are counted per forty high-power fields using sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin. (Fig. 1c). Other methods can be deployed, using stains such as Ser-10 (also known as PHH3).5

Figure 1.

Histopathology of uveal melanoma (a) haematoxylin and eosin slide showing epithelioid cells∗; (b) staining for HSP-27, which is associated with a good prognosis; (c) mitoses, stained with Ser-10 (PHH3)∗; and (d) “closed” loops∗. ∗From Damato BE et al., Progress in Retinal and Eye Research (2011).15

Uveal melanomas often contain lymphocytes and macrophages, which are mentioned in reports because of their prognostic significance, greater numbers of such cells correlating with increased mortality.

There are a variety of extravascular matrix patterns, best shown using the periodic-acid schiff (PAS) reagent, without counter-staining. The most significant are the so-called ‘closed loops’ (Fig. 1d), which correlate with aggressive behaviour.6

Molecular biology

Uveal melanomas tend to show a variety of non-random chromosomal abnormalities. The most important of these are: chromosome 3 loss, which can be partial or total (the latter being referred to as ‘monosomy 3’); chromosome 8q gains, occurring either as isodisomy 8q or trisomy; and gains in 6p, usually developing as a result of isochromosome formation. These abnormalities tend to occur as a result of chromosomal instability, with the abnormal separation of sister chromatids during cell division. Chromosome 3 loss and 8q gain are associated with a poor prognosis whereas chromosome 6p gain correlates with an improved survival probability.7,8

On the basis of gene expression profiling, uveal melanomas have been categorized as “Class 1” and “Class 2”, the latter being associated with a high-risk of metastatic disease.9

Mutations of guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha (GNAQ) and GNA11 occur in a mutually-exclusive pattern in about 80% of uveal melanomas.9 Mutations of the BRCA1-associated protein (BAP1) on chromosome 3p21.1 are also common and these are associated with metastatic disease.9,10

Pathophysiology

Choroidal melanomas initially form a dome-shaped tumour (Fig. 2 a and b). There is an overlying retinal pigment epitheliopathy, with the multilayering of retinal pigment epithelial cells, lipofuscin accumulation, drusen and retinal pigment epithelial detachment. In Caucasians, most choroidal melanomas are amelanotic or only lightly pigmented and it is the retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) proliferation that gives choroidal melanomas their dark colour (Fig. 2c). This RPE dysfunction causes retinal degeneration and atrophy, inducing symptoms such as metamorphopsia, blurring, visual field loss and photopsia. Many choroidal melanomas rupture Bruch’s membrane and the retinal pigment epithelium to prolapse into the sub-retinal space (Fig. 2c). Strangulation of the herniated tumour by the rigid Bruch’s membrane causes venous congestion and interstitial oedema so that the tumour develops a collar-stud or mushroom shape, which is virtually pathognomonic for choroidal melanoma. Some tumours invade the retina, eventually perforating this structure to reach the vitreous, possibly resulting in vitreous haemorrhage and, rarely, seeding of tumour cells around the eye. Intraocular spread of tumour can occur anteriorly to involve the ciliary body, iris and angle, as well as posteriorly, towards the optic disc, which however is only rarely invaded.

Figure 2.

Fundus photographs of choroidal melanomas showing: (a) a small tumour with overlying lipofuscin pigment; (b) a large, dome-shaped tumour with serous retinal detachment; (c) an amelanotic collar-stud melanoma; and (d) a diffuse melanoma.

Approximately, 5% of choroidal melanomas are diffuse, spreading thinly around the uvea without forming any thick nodules (Fig. 2d).

Ciliary body melanomas behave in a similar fashion to choroidal tumours. Indeed, it is often difficult to determine whether a choroidal melanoma has invaded the ciliary body or vice versa. These tumours tend to impinge on the lens to cause astigmatism, cataract and subluxation. The overlying episcleral vessels tend to become dilated and tortuous (i.e., ‘sentinel vessels’). Anterior spread often occurs into the anterior chamber (Fig. 3a). There also tends to be circumferential spread around the ciliary body, iris and angle (i.e., ‘ring melanoma’). Such circumferential spread can be diffuse and initially sub-clinical so that when treating such anterior tumours it is necessary to apply very wide lateral safety margins.

Figure 3.

Slit-lamp appearances of anterior uveal melanomas, showing: (a) a ciliary body melanoma extending into anterior chamber; (b) a pigmented, nodular iris melanoma; (c) an amelanotic, nodular iris melanoma∗; and (d) a diffuse iris melanoma with seeding. ∗From Ocular Tumours, B Damato. Butterworth Heinemann (2000).

The secondary retinal detachment can become bullous and, eventually, total. As with other causes of serous retinal detachment, there is no proliferative vitreoretinopathy so that the retina is smooth and mobile. Detached retina tends to be ischaemic and produces vasoproliferative factors, which, together with those emanating from the tumour, induce rubeosis and neovascular glaucoma. Infarction of the tumour can occur, causing uveitis, which can be severe enough to amount to panophthalmitis, with orbital cellulitis and eyelid swelling.

Iris melanomas can be nodular or diffuse or mixed (Fig. 3b–d). Some have a multinodular appearance (i.e., ‘tapioca melanoma’). The nodular melanomas tend to cause adjacent sectorial cataract and keratopathy if they come into contact with a large area of the endothelium. Diffuse melanomas spread widely, and if they extend around the angle they tend to cause secondary glaucoma. Seeding of tumour cells around the iris and angle can occur (Fig. 3d). Iris melanomas can spread posteriorly into the ciliary body, some reaching the choroid.

If left untreated, intraocular melanomas result in a blind, painful, and unsightly eye.

Extraocular spread

At any stage, uveal melanomas can spread extra-ocularly. Such spread tends to occur through pre-existing channels for ciliary arteries, vortex veins and drainage vessels.11 Extraocular tumour can be nodular, and apparently encapsulated by Tenon’s fascia, or diffuse. If neglected, orbital spread can become extensive enough to cause proptosis. Before the twentieth century, it was not uncommon for uveal melanoma to spread through the optic canal into the cranial cavity to involve the brain.

Metastatic disease

Almost 50% of all patients with uveal melanoma develop metastatic disease, which usually becomes manifest from the second post-operative year onwards.12 Only about 2% of all patients have detectable metastases when their ocular tumour is diagnosed and treated. Metastatic disease almost always involves the liver, less common sites being the lungs, skin and bone. Regional lymph nodes are rarely involved, even when the tumour shows extraocular spread. Most patients with metastases die within a year of the onset of symptoms, but long-term survivors are becoming more common thanks to advances such as partial hepatectomy, ipilimumab, selective internal radiotherapy with yttrium beads, and intra-hepatic chemotherapy, particularly using systems for isolated liver perfusion. These developments have increased the scope of screening for metastatic disease by a variety of imaging methods, such as hepatic magnetic resonance imaging, and blood tests, such as liver function tests and circulating melanoma cells.13,14

Prognostication

As with other cancers, prognostication is an important aspect of patient care, identifying high-risk patients requiring special care while allowing low-risk patients to be reassured of their good survival prospects. The pathologist is well-placed to play a valuable role in this process. This is because histological grade of malignancy and genetic type of melanoma profoundly influence prognosis.15

The clinical features associated most strongly with an increased risk of metastatic disease from posterior segment melanoma are: largest basal tumour diameter; tumour height; ciliary body involvement; and extraocular spread. These form the basis of the 7th edition of the TNM staging system (i.e., Tumour, Node, Metastasis system developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer).16 With iris melanomas, risk factors for metastasis include diffuse spread, angle involvement and secondary glaucoma.17

Histological predictors of metastasis include: melanoma cytomorphology; mitotic count; and the presence of closed loops. There is no consensus as to the proportion of melanoma cells that need to show epithelioid cytomorphology before the melanoma is termed “epithelioid”. We report the approximate percentage of epithelioid cells within a melanoma.

Metastatic disease occurs almost exclusively with melanomas showing chromosome 3 loss and/or class 2 gene expression profile, which correlate strongly with each other.9 The survival prognosis is especially poor when chromosome 3 loss and chromosome 8q gain occur together.8,18 Conversely, chromosome 6p gain is associated with a better prognosis, partly because chromosome 3 loss is less common in the presence of 6p gain and also because the survival time is longer.19

Chromosomal testing with fluorescence in situ hybridisation has largely been superseded by more sensitive methods such as multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), microsatellite analysis (MSA), array comparative genomic hybridisation (aCGH), and gene expression profiling.8,20–24 At present, we use MLPA as a first-line test, with MSA if the tumour sample is small or has a low DNA concentration (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing survival according to the presence or absence of chromosome 3 loss, determined by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification.

We have developed mathematical tools for estimating the survival prognosis after treatment of the choroidal melanoma.15 These integrate the pathological grade of malignancy with TNM clinical stage and with chromosome 3 loss, also taking age and sex into account (i.e., normal life expectancy) (Fig. 5). Our method adjusts for competing risks and generates survival curves that are accurate enough to be relevant to individual patients. This program is available online, free of charge (www.ocularmelanomaonline.com).

Figure 5.

Personalised prognostication integrating pathological findings with genetic results and clinical tumour stage. The metastatic risk is estimated by subtracting the all-cause mortality of the general population (upper curve) from that of the patient population (lower curve).

Conjunctival melanoma

Introduction

Conjunctival melanomas comprise about 2% of all ocular melanomas and are therefore very rare, even in Caucasians. As with uveal melanomas, they occur in adulthood, particularly in later life, and the incidence is similar in both sexes.25 Risk factors include: fair skin; tendency to sunburn and to have a relatively-high number of cutaneous naevi.

Histology

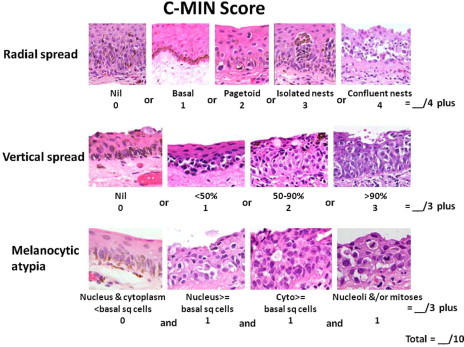

Conjunctival melanomas arise from intra-epithelial melanocytes, which are normally located in the basal layer of the epithelium and which have long dendritic processes supplying melanin pigment to adjacent epithelial cells. On malignant transformation, melanocytes lose their dendrites and demonstrate atypical features such as epithelioid morphology, with a large nucleus and prominent nucleolus (Fig. 6). In addition, they increase in number and invade the more superficial layers of the conjunctival epithelium, forming separate and confluent cells nests and increasing in density until most of the epithelium is replaced by atypical melanocytes. The rate of cellular proliferation by the neoplastic melanocytes increases so that mitotic figures are seen more readily. Eventually, the surface of the epithelium becomes “ulcerated”. Previously, this condition was referred to as ‘primary acquired melanosis (PAM) with atypia’26; however, such terminology is imprecise because it subsumes two pathological processes: both (a) melanin over-production (i.e., ‘hyper-melanosis’) and (b) proliferation of atypical melanocytes (i.e. melanocytosis). We prefer the term ‘conjunctival melanocytic intra-epithelial neoplasia (C-MIN)’, which we describe as occurring with and without atypia, according to whether or not the melanocytes show atypical cytological features and whether they demonstrate particular radial and vertical growth patterns.27 We have developed a system for scoring the degree of atypia according to these features (Fig. 5), with the maximum score being 10.27 We have also introduced the term ‘conjunctival melanoma in situ’, which refers to the more severe grades of C-MIN (i.e., score > 5).

Figure 6.

Histological grading of conjunctival melanocytic intra-epithelial neoplasia (C-MIN). From Damato B and Coupland SE. Management of conjunctival melanoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:1227–39.

Invasive melanoma is present when the conjunctival basement membrane has been breached by the neoplastic melanocytes resulting in invasion of the lamina propria. This development is of fundamental prognostic significance as the tumour cells have gained access to lymphatic channels and blood vessels, thereby giving rise to a possibility of metastatic disease. Tumour-associated lymphangiogenesis correlates with increased mortality.28

Other notable histological features, which are of prognostic value, include lymphocytic infiltration, tumour thickness, surface ulceration, depth of invasion, and surgical clearance. The presence of pagetoid spread in the epithelium is also significant as it indicates an increased risk of local recurrence, thereby influencing ocular treatment.

Molecular biology

Conjunctival melanomas are biologically different from their uveal counterparts and are more similar to cutaneous and mucous membrane melanomas. We and many others have shown, for example, that conjunctival melanomas commonly show BRAF V600E mutations, which do not occur with intraocular melanomas.29 Such BRAF mutations are of clinical significance because they indicate that the patient may respond to treatment with vemurafenib, should metastatic disease develop.30 Other mutations include CDKN1A, RUNX2, MLH1, TIMP2, MGMT, ECHS1 and others.29 To our knowledge, none of these factors have yet been shown to have prognostic value.

Pathophysiology

Conjunctival melanomas can be described as ‘in situ’ or ‘invasive’. Invasive melanomas can arise de novo, from a pre-existing naevus, or from pre-existing C-MIN (Fig. 7). Most invasive conjunctival melanomas arise in the bulbar conjunctiva, especially temporally, less common sites of origin being the caruncle, plica and tarsal conjunctiva.31–33 They can be nodular, diffuse or mixed and single or multiple. The degree of pigmentation is highly variable between tumours, even within the same patient, so that clinically the colour of the melanomas can be black, grey, brown, pink, red, yellow or white. Dilated conjunctival feeder vessels are commonly present.

Figure 7.

Slit-lamp photographs showing: (a) conjunctival melanocytic intraepithelial neoplasia; (b) diffuse, invasive conjunctival melanoma; (c) bulbar invasive conjunctival melanoma; and (d) caruncular invasive conjunctival melanoma. From Damato B and Coupland SE. Management of conjunctival melanoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:1227–39.

Local spread

Conjunctival melanomas can show pagetoid spread within the epithelium, seeding across the conjunctival surface and into the nasolacrimal passages, and invasion within the conjunctiva as well as to the surrounding tissues. Such invasion can occur circumferentially along the limbus and fornix, as well as deeply into the eye, orbit, sinuses, and cranial cavity. They can also invade the adjacent skin. Intraocular spread is more likely after inadequate surgery, especially if there is disruption of the Bowman’s membrane, which serves as a natural barrier.34 Seeding can be iatrogenic, with the transfer of malignant cells to healthy tissues by means of contaminated surgical instruments.

Metastatic disease

Metastases can occur via lymphatics to regional lymph nodes and haematogenously to other parts of the body.35,36 Risk factors predicting metastatic disease include: involvement of non-bulbar conjunctiva, particularly the caruncle; tumour thickness; histological grade of malignancy; and histological evidence of lymphatic invasion.37–39,39,40

Prognostication

The 7th edition of the TNM staging system categorizes the clinical stage of conjunctival melanomas according to circumferential spread, in terms of: (1) number of quadrants of conjunctiva involved; (2) location in bulbar or extra-bulbar conjunctiva; (3) caruncular involvement; and (4) invasion of the substantia propria, globe, eyelid, orbit, sinus and CNS. Approximately 20% of all patients with conjunctival melanoma die of metastatic disease within ten years, but mortality is much higher if the caruncle is involved.39,37

Conclusions

The management of patients with an ocular melanoma depends greatly on proper understanding of the pathology of their tumour. Pathological examination of ocular melanomas profoundly influences patient care, not only confirming the diagnosis but also indicating prognosis and hence the need for further investigation and treatment. The role of the pathologist is growing thanks to advances in molecular biology and the involvement of pathologists in this specialized field.

Contributor Information

Bertil E. Damato, Email: Bertil@Damato.co.uk.

Sarah E. Coupland, Email: s.e.coupland@liverpool.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Damato B.E., Coupland S.E. Differences in uveal melanomas between men and women from the British Isles. Eye (Lond) 2012;26:292–299. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh A.D., Bergman L., Seregard S. Uveal melanoma: epidemiologic aspects. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2005;18:75. doi: 10.1016/j.ohc.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLean I.W., Zimmerman L.E., Evans R.M. Reappraisal of Callender’s spindle a type of malignant melanoma of choroid and ciliary body. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;86:557–564. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(78)90307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jmor F., Kalirai H., Taktak A. HSP-27 protein expression in uveal melanoma: correlation with predicted survival. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.02038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angi M., Damato B., Kalirai H. Immunohistochemical assessment of mitotic count in uveal melanoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:e155–e160. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onken M.D., Lin A.Y., Worley L.A. Association between microarray gene expression signature and extravascular matrix patterns in primary uveal melanomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:748–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prescher G., Bornfeld N., Hirche H. Prognostic implications of monosomy 3 in uveal melanoma. Lancet. 1996;347:1222–1225. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90736-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damato B., Dopierala J.A., Coupland S.E. Genotypic profiling of 452 choroidal melanomas with multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6083–6092. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harbour J.W. The genetics of uveal melanoma: an emerging framework for targeted therapy. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2012.00979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harbour J.W., Onken M.D., Roberson E.D. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010;330:1410–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.1194472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coupland S.E., Campbell I., Damato B. Routes of extraocular extension of uveal melanoma: risk factors and influence on survival probability. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1778–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kujala E., Mäkitie T., Kivelä T. Very long-term prognosis of patients with malignant uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4651–4659. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres V., Triozzi P., Eng C. Circulating tumor cells in uveal melanoma. Future Oncol. 2011;7:101–109. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suesskind D., Ulmer A., Schiebel U. Circulating melanoma cells in peripheral blood of patients with uveal melanoma before and after different therapies and association with prognostic parameters: a pilot study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damato B., Eleuteri A., Taktak A.F., Coupland S.E. Estimating prognosis for survival after treatment of choroidal melanoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finger P.T. The 7th edition AJCC staging system for eye cancer: an international language for ophthalmic oncology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1197–1198. doi: 10.5858/133.8.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shields C.L., Shields J.A., Materin M. Iris melanoma: risk factors for metastasis in 169 consecutive patients. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:172–178. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White V.A., Chambers J.D., Courtright P.D. Correlation of cytogenetic abnormalities with the outcome of patients with uveal melanoma. Cancer. 1998;83:354–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parrella P., Sidransky D., Merbs S.L. Allelotype of posterior uveal melanoma: implications for a bifurcated tumor progression pathway. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3032–3037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholes A.G., Damato B.E., Nunn J. Monosomy 3 in uveal melanoma: correlation with clinical and histologic predictors of survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1008–1011. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onken M.D., Worley L.A., Tuscan M.D., Harbour J.W. An accurate, clinically feasible multi-gene expression assay for predicting metastasis in uveal melanoma. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12:461–468. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damato B., Duke C., Coupland S.E. Cytogenetics of uveal melanoma: a 7-year clinical experience. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1925–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naus N.C., van Drunen E., de Klein A. Characterization of complex chromosomal abnormalities in uveal melanoma by fluorescence in situ hybridization, spectral karyotyping, and comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;30:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tschentscher F., Prescher G., Zeschnigk M. Identification of chromosomes 3, 6, and 8 aberrations in uveal melanoma by microsatellite analysis in comparison to comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;122:13–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(00)00266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seregard S. Conjunctival melanoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:321–350. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folberg R., McLean I.W., Zimmerman L.E. Primary acquired melanosis of the conjunctiva. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(85)80061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damato B., Coupland S.E. Conjunctival melanoma and melanosis: a reappraisal of terminology, classification and staging. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2008;36:786–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heindl L.M., Hofmann-Rummelt C., Adler W. Prognostic significance of tumor-associated lymphangiogenesis in malignant melanomas of the conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2351–2360. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lake S.L., Jmor F., Dopierala J. Multiplex ligation-dependant probe amplification of conjunctival melanoma reveals common BRAF V600E gene mutation and gene copy number changes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5598–5604. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luke J.J., Hodi F.S. Vemurafenib and BRAF Inhibition: a New Class of Treatment for Metastatic Melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:9–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasser Q., Esmaeli B. Conjunctival melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2307–2308. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harooni H., Schoenfield L.R., Singh A.D. Current appraisal of conjunctival melanocytic tumors: classification and treatment. Future Oncol. 2011;7:435–446. doi: 10.2217/fon.11.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Damato B., Coupland S.E. Clinical mapping of conjunctival melanomas. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1545–1549. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.129882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandinha T., Russell H., Kemp E., Roberts F. Malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva with intraocular extension: a clinicopathological study of three cases. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245:431–436. doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savar A., Esmaeli B., Ho H. Conjunctival melanoma: local-regional control rates, and impact of high-risk histopathologic features. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savar A., Ross M.I., Prieto V.G. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for ocular adnexal melanoma: experience in 30 patients. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2217–2223. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Damato B., Coupland S.E. An audit of conjunctival melanoma treatment in Liverpool. Eye. 2009;23:801–809. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paridaens A.D., Minassian D.C., McCartney A.C., Hungerford J.L. Prognostic factors in primary malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva: a clinicopathological study of 256 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:252–259. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.4.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shields C.L., Markowitz J.S., Belinsky I. Conjunctival melanoma: outcomes based on tumor origin in 382 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tuomaala S., Kivelä T. Metastatic pattern and survival in disseminated conjunctival melanoma: implications for sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:816–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]