Abstract

Trachoma remains the leading cause of preventable corneal blindness in developing countries. The disease is contracted in early childhood by repeated infection of the ocular surface by C. trachomatis. Initial clinical manifestation is a follicular conjunctivitis which if not treated on timely basis, may lead to conjunctival and eyelid scarring that may eventually result in corneal scarring and loss of vision. Over the past two decades, a remarkable reduction in the prevalence of active trachoma has occurred due to the World Health Organization’s (WHOs) program GET 2020 for the elimination of trachoma with adoption of the SAFE strategy incorporating Surgery, Antibiotic treatment, Facial cleanliness and Environmental hygiene. However, patients who already had infection at young age may present with adnexal-related complications of trachomatous scarring that may cause corneal scarring and visual loss. These patients may present with evidence of trichiasis/entropion as well as eyelid retraction. Lacrimal complications may include nasolacrimal-duct obstruction, dacryocystitis and canaliculitis requiring intervention. In addition to the increased risk for corneal scarring, trichiasis/entropion may further increase the risks for microbial keratitis in patients who may have unrecognized dacryocystitis and canaliculitis. Female patients may have more trachomtous-related complications and may present at an early age. Available evidence indicates that SAFE strategy may be effective and on the right track towards achieving GET 2020 goal for the eradication of trachoma.

Keywords: Trachoma, Chlamydia trachomatis, Visual loss, Adnexal complications, Evaluation, Treatment

1. Scope of the problem

Trachoma is the most common infectious cause of blindness worldwide. It afflicts some of the poorest regions of the globe, predominantly in Africa and Asia (Al-Rifai, 1988; Solomon and Mabey, 2007). The disease is initiated in early childhood by repeated infection of the ocular surface by Chlamydia trachomatis, an intracellular gram-negative bacterium (Burton, 2007). During acute infection, the disease may remain asymptomatic but some patients may complain of eye redness, irritation and discharge (Burton, 2007). The principal initial clinical manifestation is a follicular conjunctivitis. A population based survey of trachoma and blindness from a rural Nile Delta hamlet, a trachoma hyper-endemic region found that active trachoma was common among pre-school children (Courtright et al., 1989). Among inhabitants 25 years or older, 90% had substantial conjunctival scarring. Severe conjunctival scarring was common among women (84%) than men (58%), and three-quarters of older women had trichiasis/entropion compared with 57% of older men. Blindness was associated with old age; 17% of residents aged 50 and over had significant blindness (Courtright et al., 1989). Trachoma is one of the main cause of preventable blindness in Saudi Arabia (Tabbara and Ross-Degnan, 1986; Tabbara and Al-Omar, 1997; Tabbara, 2001). Early surveys during 1955–70 in Eastern Province revealed prevalence rate of trachoma as 100% in Al Hasa, 98% in Qatif Oasis and 93% in Qatif town dwellers (Murray et al., 1960; Nichols et al., 1966, 1967, 1969; McComb and Nichols, 1969, 1970; Bobb and Nichols, 1969; Bell et al., 1970). Preliminary study by Ministry of Health, Eastern Province in 1986 revealed 3.74% of the population had blindness among them 10.1% due to trachoma (Tabbara and Al-Omar, 1997). In 1986, Ministry of Health established Regional Prevention of Blindness and Ophthalmic Medical Education Committee, Eastern Province with six sub-divisions in Al Hasa, Qatif, Dammam, Al Khobar/Dhahran, Jubail and Hafr Al Batin. The whole health care was divided in primary, secondary and tertiary level in 1987 and incorporated primary eye health care with primary health care. The Trachoma Center was started in Al Hasa in 1987 and a mass trachoma eradication program was launched in 1988. Improvement in socio-economic status and structured health care system over the following 10 years leads to public awareness, prevention and treatment of bulk of active trachoma in this region (Tabbara and Al-Omar, 1997). More recently, provision of comprehensive eye care by completing preliminary tertiary level care Eye Hospital in Dhahran has further reduced the incidence of active trachoma below 0.5%. In 1984, evidence of trachoma (active and inactive) was found among 22.2% of the Saudi population; 6.2% of them had evidence of active trachoma. In addition, 17.4% had conjunctival scarring as a result of old trachoma, and 1.5% had entropion or trichiasis. In 1994, clinical evidence of trachoma (active and inactive) was found among 10.7% of the Saudi population while 2.6% had active trachoma. Conjunctival scarring as a result of healed trachoma was seen in 8.1% and 0.2% had trichiasis and entropion (Tabbara and Al-Omar, 1997).

2. Risk factors for C. trachomatis infection

Trachoma prevalence is disproportionately high among women and children in poor rural communities. In particular, risk factors include lack of facial cleanliness, poor access to water supplies, lack of latrines, and a large number of flies. House-hold overcrowding, and the lack of clean water are factors that predispose to the transmission of the disease (Barenfanger, 1975). In one of the study that compared trends in the prevalence of active inflammatory trachoma among children under 10 years of age in Marakissa (a small rural village in the Gambia) between the results of eye examinations conducted in 1959, 1987, and 1996, the prevalence of active trachoma infection dropped from 65.7 cases per 100 in 1959 to 2.4 per 100 in 1996 (Dolin et al., 1997). Declines were also recorded among children 10–19 years old (from 52.5 to 1.4/100) and among those 20 years and older (from 36.7 to 0 cases/100). This dramatic fall, which occurred without any specific trachoma control programs in the area, was attributed to both improvements in socio-economic standards and the training of village health workers and traditional birth attendants in eye care (Dolin et al., 1997). Another study of trachoma control in Burma over a 30-years period also found a remarkable decline in trachomatous blindness (Evans et al., 1996). An epidemiological study of trachoma in Central Tanzania, found that active inflammatory disease peaked in pre-school children, with 60% showing signs of trachoma (West et al., 1991). Evidence of past infection, scarring, trichiasis, and corneal opacity, rose with age. In this population, 8% of those over age 55 had trichiasis/entropion. Females of all ages had more trachoma than males, with a fourfold increased risk of trichiasis observed in females. Women who were taking care of children appeared to have more active disease than non-caretakers. Evidence of clustering of trachoma by village, and within village, by neighbor-hood was also found. Clustering persisted even after accounting for differences in distance to water, local religion, and proportion of children with unclean faces. These findings may have important implications for a trachoma control strategy (West et al., 1991). Trachoma remains a public health issue in Central Australia. Landers et al. (2005), found that although the prevalence of the cicatricial and blinding consequences of trachoma was decreasing in patients aged 40 years or greater, it still remained a significant health issue in an indigenous population within Central Australia when compared with other areas of Australia.

Presence of distichiasis and/or dysplastic eyelashes in trachomatous trichiasis cases warrants further analytical studies to confirm the observation and establish any causal association (Khandekar et al., 2004). In a prospective evaluation of the prevalence of distichiasis and/or dysplastic eyelashes among trachomatous trichiasis cases at the oculoplasty unit of a hospital in Oman over 3 months period, among 80 cases, 58 (72.5%) had abnormal eyelashes in addition to trachomatous trichiasis (Khandekar et al., 2004). Dysplastic and distichiasis eyelashes were significantly more prevalent in trachomatous trichiasis cases aged <50 years and those with entropion. Severe trichiasis reflects the magnitude of the trachoma problem in areas such as Ethiopia. Visual impairment due to trichiasis may be highly associated with disease severity and duration (Figs. 1 and 2). Among the 1635 individuals with trichiasis presenting for surgery in the Wolayta Zone of Ethiopia, 82% had bilateral trichiasis and 91% of them reported trichiasis duration of >2 years (Melese et al., 2005). Epilation was practised by over three fourths of the study subjects. A high proportion of patients tested positive for ocular C. trachomatis at presentation; among them 17% had monocular blindness and 8% had blindness in their both eyes. Corneal opacity was highly associated with the trichiasis duration, severity and visual loss (Melese et al., 2005).

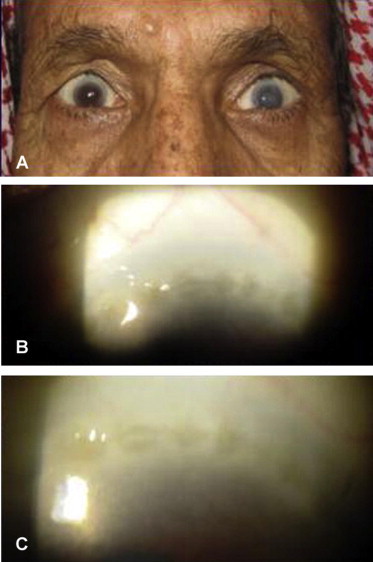

Figure 1.

A 75-years-old-male patient with history of severe complications of trachoma in the form of eyelid retraction, trichiasis/entropion and severe dry eye syndrome.

Figure 2.

An 85-years-old male patient with long standing history of eyelid trichiasis/entropion and associated corneal scarring presented with inability to open his eyes. Surgical correction in the form of entropion repair resulted in patient’s ability to open his eyes.

3. Mechanism of scarring

Trachoma appears to initiate a vicious cycle of mucus deficiency, chronic conjunctival inflammation and conjunctival scarring (Blodi et al., 1988). The basic mechanisms involved in tissue damage and scarring following C. trachomatis remain to be elucidated (Fig. 3). In specimens taken from patients with active trachoma, the inflammatory infiltrate is organized as lymphoid follicles in the underlying stroma and impression cytology shows cytoplasmic elementary bodies. Immunohistochemical studies of conjunctival biopsies from children with active trachoma demonstrate the presence of both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses (Abu el-Asrar et al., 2001). In the active trachomatous conjunctivitis, macrophages may play an active role in conjunctival scarring by up-regulating local production of extracellular matrix by the expression of the fibrogenic and angiogenic connective tissue growth factor (Abu El-Asrar et al., 2006). In the chronic phase, inflammation causes scarring of the conjunctiva followed by dry eye which can result in blindness. Trachoma may cause dryness of the eye by decreased mucus production and aqueous secretions (Fig. 1). Light microscopy may show subepithelial fibrosis, membranes formation, squamous metaplasia, loss of goblet cells, pseudogland formation, degeneration of orbicularis oculi muscle fibres, subepithelial vascular dilatation, localized perivascular amyloidosis and subepithelial lymphocytic infiltration. Conjunctival impression cytology may reveal significant reduction of goblet cell population among these patients. Accessory lacrimal glands and ducts may be compromised by subepithelial infiltration and scarring. The contraction of the subepithelial fibrous tissue formed by collagen fibers and anterior surface drying are the main factors contributing to the chronic cicatrization and entropion formation (Guzey et al., 2000). Severe cases of trachoma may lead to contracture of the conjunctiva and deeper tissues including Müller muscle and the tarsal plate. Hence, the upper eyelids of these patients may show eyelid retraction that also may show as eyelid lag on patient’s down-gaze (Alsuhaibani and Al-Fakey, 2007).

Figure 3.

A 60-years-old male with bilateral upper eyelid retraction (A) due to tarsal/conjunctival contraction and corneal scarring as Herbert’s pits (B and C), characteristic of trachoma.

4. Mechanism of vision loss in trachoma

Repeated eye infection with C. trachomatis organism may trigger recurrent chronic inflammatory episodes leading to the development of conjunctival scarring. This scar tissue contracts, distorting the eyelids (entropion) causing contact between the eyelashes and the surface of the eye (trichiasis) compromising the cornea with blinding opacification (Tabbara, 2001). Trichiasis/entropion may be the most common single factor leading to the significant blinding complication. Infact, entropion may be the most significant predictor of corneal opacity (Figs. 1, 2 and 4). Eyelids of patients with inactive trachoma may be thickened. This thickening could be attributed to trachomatous changes in the conjunctiva and tarsus. Light microscopy studies of tarsal plates and palpebral conjunctivae obtained from the upper eyelids of patients having inactive trachoma show a thick and compact subepithelial fibrous membrane adherent to the tarsal plate (Al-Rajhi et al., 1993). Other histopathologic findings include atrophy of the meibomian glands with thickening of the acinar basement membrane, loss of goblet cells, retention cysts, and hyaline degeneration of the tarsal plate with focal replacement by adipose tissue (Al-Rajhi et al., 1993). Chronic trichiasis and eyelid entropion can result in significant corneal scarring and associated visual loss. In a retrospective study of 137 patients from Senegal who underwent 199 surgical procedures, over 51% of them already had some kind of corneal complications due to abnormalities of their eyelid conditions. The average age of these patients was 49 years with a higher percentage of women (Ndoye et al., 1997). Entropion is the most significant predictor of corneal opacity. Cross sectional associations suggest that epilation may not be helpful for eyes with mild entropion, but may offer protection against corneal opacity in eyes with moderate to severe entropion. Epilation may not be a substitute for trichiasis surgery, as 43% of eyes with severe entropion that have epilation performed may still have corneal opacities (West et al., 2006). Marginal rotation by a posterior approach is an effective and simple procedure with fewer complications, even when performed by non-ophthalmologists. A study from the indigenous population from the Upper Rio Negro basin of Brazil, on 73 upper eyelids of 46 Indians (35 females, 11 males) with cicatricial upper eyelid trichiasis/entropion requiring surgery which had been performed by non-ophthalmologist physician who had general surgery experience with an extremely short period (one week) of ophthalmic training has been reported (Soares and Cruz, 2004). The surgery was performed by using a marginal rotational procedure by a posterior approach. Reevaluation 6 months after surgery revealed that 56 eyelids (76.7%) were free from trichiasis, whereas residual trichiasis was observed in 17 eyelids (23.3%) of 10 subjects. In these cases, trichiasis was either lateral or medial to the central portion of the lid. Of these 10 patients, only four reported that the surgery did not improve the irritative symptoms (Soares and Cruz, 2004).

Figure 4.

A 68-years-old female with severe trichiasis/entropion and corneal scarring requiring penetrating keratoplasty for her right eye. She had previous multiple hyfercations and entropion repair of her right upper eyelid resulting in loss of anterior eyelid.

Surgery for entropion may result in healing of superficial keratopathy and improve tear film stability. The realigned eyelid margin may spread tears evenly and efficiently, contributing to improved vision. These changes may take place over 1–90 days and should be considered when contemplating keratoplasty, intraocular or keratorefractive procedures after entropion correction (Monga et al., 2008). Patients with trachomatous trichiasis/entropion suffer in the physical, psychological and environmental domains of health-related quality of life even when vision is normal. Timely intervention is essential not only to prevent corneal blindness but also to reduce the suffering caused by the non-visual symptoms. In one prospective, case-controlled, interventional study, health-related quality of life among the 60 patients with trachomatous trichiasis/entropion was found to be improved after intervention (Dhaliwal et al., 2006). Cornea grafting may be necessary in patients who have significant corneal opacity despite correction of trichiasis/entropion (Fig. 4). A recent study from King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital, treating 127 patients with trachomatous corneal scarring undergoing penetrating keratoplasty revealed that the procedure had a good prognosis for graft survival in over 80% of patients over a 4-year period (Al-Fawaz and Wagoner, 2008). Patients with mild or well-controlled ocular surface disease and absent or previously surgically corrected eyelid abnormalities had the best visual outcome.

5. Mechanism of nasolacrimal system damage

Trachomatous scarring can also affect nasolacrimal system drainage (Figs. 5 and 6). A clinical study of the lacrimal complications of trachoma from an eastern province of Saudi Arabia revealed that among the 579 Saudi Arabian patients examined, 446 (77%) showed clinical evidence of trachoma, 62 of whom had severe inactive trachoma (Tabbara and Bobb, 1980). From this group the following lacrimal complications were observed: dry eye syndrome, punctal phimosis, punctal occlusion, canalicular occlusion, nasolacrimal-duct obstruction, dacryocystitis, dacryocystocele, and dacryocutaneous fistula. Histopathologic examination of seven lacrimal-sac biopsies showed the same cicatrizing changes seen in 14 conjunctival biopsies (Tabbara and Bobb, 1980). Patients with follicular conjunctivitis caused C. trachomatis infection may develop canaliculitis, canalicular obstruction, dacryocystitis and nasolacrimal-duct obstruction. Bacteriological examination of conjunctival smears in patients with follicular conjunctivitis may show co-infection with other microbial organisms. It has been suggested that all cases of chronic follicular conjunctivitis with lacrimal inflammation that are resistant to topical antibiotics should suggest the possibility of infection with C. trachomatis (Janssen et al., 1993). In the patients with a history old trachomatous scarring, lacrimal-sac biopsies performed during dacryocystohinostomies has revealed loss of the epithelial lining in the lacrimal sac (Rice and Kersten, 1988). The authors theorized that the common canalicular as well as nasolacrimal-duct obstructions were presumably secondary to trachoma. These specimens were negative for Chlamydia supporting evidence for clinically inactive disease.

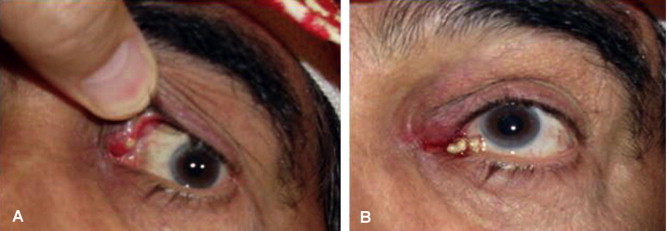

Figure 5.

A 68-years-old diabetic patient had recurrent episodes of left-sided microbial keratitis and failed penetrating keratoplasty; which were attributed to untreated chronic dacryocystitis.

Figure 6.

A 63-years-old male presented with 1-year history of left upper eyelid swelling un-responsive to previous curettage (A). Focal pressure over the left upper canaliculi resulted in excretions (B).

6. Treatment: medical and surgical

Both non-surgical and surgical interventions have been found to be cost effective means of preventing trachomatous visual impairment. The World Health Organization (WHO) is leading a global effort to eliminate Blinding Trachoma, through the implementation of the SAFE strategy (Bailey and Lietman, 2001). This involves surgery for trichiasis, antibiotics for infection, facial cleanliness (hygiene promotion) and environmental improvements to reduce transmission of the organism. With full implementation, the program promises significant reduction in the spread of acute infection. However, there are significant gaps in the evidence base and optimal management remains uncertain (Burton, 2007). Recently, several affective therapeutic modalities for trachoma have been proven useful. Azithromycin oral single dose has been found to be safe and effective in children with active trachoma. Conjunctival biopsy specimens obtained from patients receiving a single oral dose of azithromycin show sustained high levels of the drug (above MIC of Chlamydia) for up to 2 weeks after intake. These prolonged high levels of azithromycin in the conjunctival tissue following a single oral dose make the drug suitable for the treatment of endemic trachoma (Tabbara, 2001). Biannual mass distribution of azithromycin may locally eliminate ocular chlamydial infection from severely affected communities. A cross-sectional survey of two villages in Africa, previously enrolled and monitored over 42 months as part of a larger group randomized clinical trial, six biannual mass treatments with oral azithromycin resulted in significant reduction of clinical active trachoma and laboratory evidence of chlamydial ribonucleic acid (RNA) (Biebesheimer et al., 2009). Clinical trachoma activity in children aged 1–5 years decreased from 78% and 83% in the two villages before treatment to 17% and 24% at 42 months. Polymerase chain reaction evidence of infection in the same age group decreased from 48% to 0% in both villages at 42 months. When all age groups were examined, there were zero cases with evidence of chlamydial RNA among 758 total villagers tested (Biebesheimer et al., 2009).

Management of trachomatous cicatricial trichiasis and entropion of the eyelids presents a difficult problem (Yorston and Mabey, 2006). Over the years, many surgical approaches have been developed to address it (Yorston and Mabey, 2006; Cockburn, 1943; Chandra and Taneja, 1964; Sandford-Smith, 1976; Thommy, 1980; Niederer and Sutter, 1981; Rice et al., 1989; Teichmann, 1988; Nasr, 1991; Bujger et al., 2004; Sadiq and Pai, 2005). Although the WHO document WHO/PBL/93.29 recommends the bilamellar tarsal rotation operation for trachomatous entropion, Bujger et al. (2004), has described an operation that has proved to be very reliable. It is a modified tarsal wedge resection and the eversion splinting-grey line incision. A possible additional correction of the grey line incision may improve the results. By this method, the rate of failed operations, which consisted of incomplete closure of the lids or more than two inverted lashes remaining, was 6.9% (Bujger et al., 2004). A modified version of Wies’s operation offers the correction of cicatricial entropion in which the most important modification being a different plane for the incision through the eyelid (Sandford-Smith, 1976). Certain interventions have been shown to be more effective at eliminating trichiasis. Most effective surgery, however, is the full-thickness incision of the tarsal plate and rotation of the terminal tarsal strip 180°. Full thickness incision of the tarsal plate and rotation of the lash-bearing lid margin through 180° is probably the best technique and is preferable in the community settings. The use of double-sided sticking plaster is more effective than epilation as a temporary measure. Surgery may be carried out by an ophthalmologist or a trained ophthalmic assistant. The addition of azithromycin treatment at the time of surgery may not improve the outcome (Yorston and Mabey, 2006). A modified surgical technique combining bilamellar tarsal margin rotation procedure with blepharoplasty has been advocated (Sadiq and Pai, 2005). With this technique, the eyelids as well as the normal eyelashes can be rotated away from the surface of the eye. These eyes may have adequate lid closure and regular lid margin. This modified technique prevents any overhanging baggy fold of skin at operation site. Further, the modified technique of combining bilamellar tarsal rotation procedure with blepharoplasty appears to be an effective surgical technique in the management of the trachomatous cicatricial entropion of the upper eye lid. It achieves successful anatomical correction along with more acceptable cosmetic appearance (Sadiq and Pai, 2005). Isolated cilia posterior to normal lash line can be treated by hyfercation.

In developing countries, where manpower and other resources are limited and patient-load high, ophthalmic surgeons should choose a procedure that is simple, quick and effective. In a prospective study lids with moderate or severe trachomatous entropion were compared for the efficacy of three common surgical procedures of increasing complexity in the correction of trachomatous entropion by either terminal tarsal rotation, tarsal rotation with tarso-conjunctival advancement, or anterior lamellar repositioning with lid margin split and wedge resection of tarsus (Dhaliwal et al., 2004). The procedures were compared for improvement of symptoms, duration of surgery, cosmesis, rate and type of complications, anatomical correction, failure and recurrence. Terminal tarsal rotation, the simplest technique took significantly less time. The three procedures were comparable in achieving cosmesis, anatomical correction, and rate of complications. In general, terminal tarsal rotation after transverse tarsotomy should be the procedure of choice in the correction of moderate or severe (without lid gap) trachomatous entropion. A lid-splitting procedure by using a bare-tarsus technique and omitting any grafting has been recommended by Teichmann (1988), in patients with trachomatous entropion. Additional radial incisions at the nasal and temporal edges of the anterior lamella may be advantageous, as the often superimposed blepharospasm can be abolished by the weakening of the tarsal part of the orbicularis muscle (Teichmann, 1988). Also, there may be low tendency for the recessed anterior lamella to creep back down to the lid margin. Cicatricial entropion with hard palate mucous membrane grafting for both upper and lower eyelid surgery may offer high symptomatic and anatomical cure rates. The requirement for further surgical intervention may be low (Swamy et al., 2008).

In conclusion, by the establishment of the GET 2020 goal, the WHO has set an ambitious target for country programs. The currently recommended SAFE strategy targets all key elements believed to be necessary for a short- and long-term intervention program. Additional research may enhance the implementation of the SAFE strategy. In the current climate of significant political and social momentum for trachoma control, the SAFE strategy is a safe bet to accomplish the eradication of blinding trachoma (West, 2003).

References

- Abu el-Asrar A.M., Geboes K., Missotten L. Immunology of trachomatous conjunctivitis. Bull. Soc. Belge. Ophtalmol. 2001;280:73–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu El-Asrar A.M., Al-Kharashi S.A., Missotten L., Geboes K. Expression of growth factors in the conjunctiva from patients with active trachoma. Eye. 2006;20:362–369. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fawaz A., Wagoner M.D. King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital corneal transplant study group. Penetrating keratoplasty for trachomatous corneal scarring. Cornea. 2008;27:129–132. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318158b49e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rajhi A.A., Hidayat A., Nasr A., Al-Faran M. The histopathology and the mechanism of entropion in patients with trachoma. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1293–1296. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rifai K.M. Trachoma through history. Int. Ophthalmol. 1988;12:9–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00133774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsuhaibani A.H., Al-Fakey Y.H. Unilateral eyelid lag and retraction as sequelae of trachoma. Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007;23:169–170. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000256160.40173.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey R., Lietman T. The SAFE strategy for the elimination of trachoma by 2020: will it work? Bull. World Health Organ. 2001;79:233–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barenfanger, J., 1975. Studies on the role of the family unit in the transmission of trachoma. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 24, 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bell S.D., McComb D.E., Nichols R.L., Roca-Garcia M. Studies on trachoma. VII. Isolation of a mixture of type 1 and type 2. Trachoma strains from a child in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1970;19:842–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biebesheimer J.B., House J., Hong K.C., Lakew T., Alemayehu W., Zhou Z., Moncada J., Rogér A., Keenan J., Gaynor B.D., Schachter J., Lietman T.M. Complete local elimination of infectious trachoma from severely affected communities after six biannual mass Azithromycin distributions. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2047–2050. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blodi B.A., Byrne K.A., Tabbara K.F. Goblet cell population among patients with inactive trachoma. Int. Ophthalmol. 1988;12:41–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00133780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobb A.A., Jr., Nichols R.L. Influence of environment on clinical trachoma in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1969;67:235–243. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(69)93152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujger Z., Cerovski B., Kovacevic S., Nasic M., Pokupec R., Tojagic M. A contribution to the surgery of the trachomatous entropion and trichiasis. Ophthalmologica. 2004;218:214–218. doi: 10.1159/000076848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton M.J. Trachoma: an overview. Br. Med. Bull. 2007;84:99–116. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldm034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra P., Taneja K.L. Correction of cicatricial entropion of upper lid by insertion of acrylic plate. J. All India Ophthalmol. Soc. 1964;12:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn C. An operation for entropion of rachoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1943;27:308–310. doi: 10.1136/bjo.27.7.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtright P., Sheppard J., Schachter J., Said M.E., Dawson C.R. Trachoma and blindness in the Nile Delta: current patterns and projections for the future in the rural Egyptian population. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1989;73:536–540. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.7.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaliwal U., Monga P.K., Gupta V.P. Comparison of three surgical procedures of differing complexity in the correction of trachomatous upper lid entropion: a prospective study. Orbit. 2004;23:227–236. doi: 10.1080/01676830490518714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaliwal U., Nagpal G., Bhatia M.S. Health-related quality of life in patients with trachomatous trichiasis or entropion. Ophthal. Epidemiol. 2006;13:59–66. doi: 10.1080/09286580500473803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolin P.J., Faal H., Johnson G.J., Minassian D., Sowa S., Day S., Ajewole J., Mohamed A.A., Foster A. Reduction of trachoma in a sub-Saharan village in absence of a disease control programme. Lancet. 1997;349:1511–1512. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)01355-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans T.G., Ranson M.K., Kyaw T.A., Ko C.K. Cost effectiveness and cost utility of preventing trachomatous visual impairment: lessons from 30 years of trachoma control in Burma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1996;80:880–889. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.10.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzey M., Ozardali I., Basar E., Aslan G., Satici A., Karadede S. A survey of trachoma: the histopathology and the mechanism of progressive cicatrization of eyelid tissues. Ophthalmologica. 2000;214:277–284. doi: 10.1159/000027504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen K., Gerding H., Busse H. Recurrent canaliculitis and dacryocystitis as a sequela of persistent infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Ophthalmologe. 1993;90:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandekar R., Kidiyur S., Al-Raisi A. Distichiasis and dysplastic eyelashes in trachomatous trichiasis cases in Oman: a case series. East Mediterr. Health J. 2004;10:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landers J., Kleinschmidt A., Wu J., Burt B., Ewald D., Henderson T. Prevalence of cicatricial trachoma in an indigenous population of Central Australia: the Central Australian Trachomatous Trichiasis Study (CATTS) Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2005;33:142–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McComb D.E., Nichols R.L. Antibodies to trachoma in eye secretions of Saudi Arab children. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1969;90:278–284. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McComb D.E., Nichols R.L. Antibody type specificity to trachoma in eye secretions of Saudi Arab children. Infect. Immun. 1970;2:65–68. doi: 10.1128/iai.2.1.65-68.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melese M., West E.S., Alemayehu W., Munoz B., Worku A., Gaydos C.A., West S.K. Characteristics of trichiasis patients presenting for surgery in rural Ethiopia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1084–1088. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.066076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monga P., Gupta V.P., Dhaliwal U. Clinical evaluation of changes in cornea and tear film after surgery for trachomatous upper lid entropion. Eye. 2008;22:912–917. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray E.S., Bell S.D., Jr., Hanna A.T., Nichols R.L., Snyder J.C. Studies on trachoma. 1. Isolation and identification of strains of elementary bodies from Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1960;9:116–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr A.M. Eyelid complications in trachoma: diagnosis and management. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh) 1991;69:200–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1991.tb02711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndoye P.A., Ngom A., Ndiaye C.S., Ba E.A., Ndiaye P.A., Ndiaye M.R., Wade A. Trachomatous entropion trichiasis at the ophthalmologic clinic of Dantec CHU (apropos of 199 cases) Rev. Int. Trach. Pathol. Ocul. Trop. Subtrop Sante Publique. 1997;74:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols R.L., Bell S.D., Jr., Murray E.S., Haddad N.A., Bobb A.A. Studies on trachoma. V. Clinical observations in a field trial of bivalent trachoma vaccine at three dosage levels in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1966;15:639–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols R.L., Bobb A.A., Haddad N.A., McComb D.E. Immunofluorescent studies of the microbiologic epidemiology of trachoma in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1967;63:1372–1408. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)94123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols R.L., Bell S.D., Jr., Haddad N.A., Bobb A.A. Studies on trachoma. VI. Microbiological observations in a field trial in Saudi Arabia of bivalent rachoma vaccine at three dosage levels. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1969;18:723–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederer, W., Sutter, E., 1981. Different methods of treatment of upper lid entropion (author’s transl.). Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 178, 464–468. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rice C.D., Kersten R.C. Absence of Chlamydia in trachomatous lacrimal sacs. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1988;105:203–206. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C.D., Kersten R.C., Al-Hazzaa S. Cryotherapy for trichiasis in trachoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1180–1182. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020246033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq M.N., Pai A. Management of trachomatous cicatricial entropion of the upper eye lid: our modified technique. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2005;17:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandford-Smith J.H. Surgical correction of trachomatous cicatricial entropion. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1976;60:253–255. doi: 10.1136/bjo.60.4.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares O.E., Cruz A.A. Community-based transconjunctival marginal rotation for cicatricial trachoma in Indians from the Upper Rio Negro basin. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2004;37:669–674. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000500007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, A., Mabey, D., 2007. Trachoma. Clin. Evid. (Online). 7, pii: 0706.

- Swamy B.N., Benger R., Taylor S. Cicatricial entropion repair with hard palate mucous membrane graft: surgical technique and outcomes. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2008;36:348–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabbara K.F. Trachoma: a review. J. Chemother. 2001;13(Suppl. 1):18–22. doi: 10.1080/1120009x.2001.11782323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabbara K.F. Blindness in the Eastern Mediterranean countries. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2001;85:771–775. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabbara K.F., Al-Omar O.M. Trachoma in Saudi Arabia. Ophthal. Epidemiol. 1997;4:127–140. doi: 10.3109/09286589709115720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabbara K.F., Bobb A.A. Lacrimal system complications in trachoma. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:298–301. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabbara K.F., Ross-Degnan D. Blindness in Saudi Arabia. JAMA. 1986;255:3378–3384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann, K.D., 1988. Correction of severe upper eyelid entropion. Int. Ophthalmol. 12, 37–39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Thommy C.P. A modified technique for correction of trachomatous cicatricial entropion. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1980;64:296–298. doi: 10.1136/bjo.64.4.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West S.K. Blinding trachoma: prevention with the safe strategy. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003;69:18–23. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.69.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West S.K., Munoz B., Turner V.M., Mmbaga B.B., Taylor H.R. The epidemiology of trachoma in central Tanzania. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1991;20:1088–1092. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.4.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West E.S., Munoz B., Imeru A., Alemayehu W., Melese M., West S.K. The association between epilation and corneal opacity among eyes with trachomatous trichiasis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006;90:171–174. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.075390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorston, D., Mabey, D., Hatt, S., Burton, M., 2006. Interventions for trachoma trichiasis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3 (CD004008). [DOI] [PubMed]