Abstract

This report provides an overview of fungal rhinosinusitis with a particular focus on acute fulminant invasive fungal sinusitis (AFIFS). Imaging modalities and findings that aid in diagnosis and surgical planning are reviewed with a pathophysiologic focus. In addition, the differential diagnosis based on imaging suggestive of AFIFS is considered.

Keywords: Acute fulminant invasive fungal sinusitis, Fungal rhinosinusitis, Imaging, Computed tomography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Introduction

Fungal rhinosinusitis encompasses a wide spectrum of fungal infections ranging from mildly symptomatic to rapidly fatal. Fungal colonization of the upper and lower airways is a common condition secondary to the ubiquitous presence of fungal spores in the air. Aspergillus species are the most prevalent colonizers of the sinuses.1 However, colonization is distinct from infection as the majority of colonized patients do not become ill with fungal infections. It is the interplay of the organism with the host’s immune system or lack thereof that results in the various manifestations of disease. Infections are distinguished by whether they are invasive and noninvasive. Based upon the International Society for Human and Mycology Group (2008), invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is classified as acute, chronic, or granulomatous.2 The non-invasive forms of fungal sinusitis are allergic fungal rhinosinusitis and the fungus ball (fungal mycetoma) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristic features of Fungal Rhinosinusitis.

| Type | Organisms | IS | Features | Sinuses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFIFS | Aspergillus; Zygomycetes | Yes | Rapid angioinvasion with tissue infarction | Multiple; unilateral |

| CIFRS | A. fumigatus Zygomycetes | Mild | Chronic sinusitis with slow tissue invasion | Multiple; maxillary less |

| GIFRS | Aspergillus flavus | No | Enlarging cheek mass or proptosis | Multiple |

| Allergic | Many | No | Pansinus expansion | Multiple or all |

| Fungus Ball | Aspergillus fumigatus | Mild | One sinus with proximal obstruction | Maxillary most common |

Abbreviations: IS, Immunocompromised State.; A, Aspergillus; AFIFS, acute fulminant invasive fungal sinusitis; CIFRS, chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis; GIFRS, granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis.

Acute fulminant invasive fungal sinusitis

Acute fulminant invasive fungal sinusitis (AFIFS) occurs predominantly in patients with profound immunosuppression.3–5 Rarely, it has been reported in otherwise healthy individuals.6 It can be fatal over days and is characterized by invasion of the blood vessels with resulting tissue infarction. Unlike the other forms of fungal rhinosinusitis, anatomic abnormalities that cause sinus pooling, such as nasal polyps or chronic inflammatory states, do not appear to be significant risk factors for AFIFS.4

AFIFS is usually due to Aspergillus species or fungi from the class Zygomycetes, including Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, Absidia, and Mucor.7 In diabetic patients, roughly 80% of AFIFS is secondary to species from the class Zygomycetes; in neutropenic patients, 80% of AFIFS is secondary to Aspergillus species.6,8 As with all forms of fungal rhinosinusitis, AFIFS begins in the nose and paranasal sinuses after the inhalation of fungal spores.9 After germination, hypha invade arteries and cause tissue necrosis by forming fungal thrombi and a fibrin reaction, resulting grossly in a “dry” gangrene appearance.10 Spread to orbital and intracranial structures occurs through direct vascular invasion and occasionally through embolic seeding.11 This notion of angioinvasion has been supported by histopathologic examination with demonstration of fungal growth along the internal elastic lamina of blood vessels resulting in dissection away from the media, as well as hyphal growth into the vessel lumen causing endothelial dysfunction and thrombosis. 12 Examples of direct extension include invasion to the frontal lobes via the ophthalmic arteries or the cribriform plate, or through the cavernous sinus via the orbital apex.11 In addition, dissemination to distant organs has been described.13

Symptoms of the infection are related to tissue invasion. As the infection spreads from the sinuses into the orbit, several clinical findings may manifest. Periorbital edema, ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, visual loss, proptosis, and intraocular involvement can all be signs of orbital infection (Fig. 1).4 Decreased mentation is particularly concerning for central nervous system involvement.

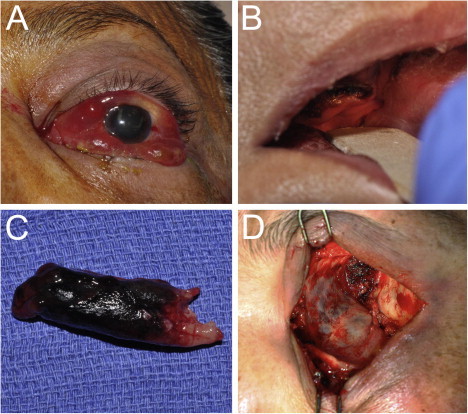

Figure 1.

(A) 58 year-old female in diabetic ketoacidosis presents with decreased vision, chemosis, proptosis and ophthalmoplegia on the left side concerning for AFIFS. (B) Oral exam demonstrates poor dental hygiene and necrosis of the hard palate. (C) Endoscopic exam reveals necrosis of the left inferior turbinate which was removed during debridement. Tissue culture eventually grew Rhizopus microsporious. (D) Orbital exenteration was performed in conjunction with nasal and sinus debridement because of significant orbital involvement seen on imaging. Involvement of the ethmoid sinus air cells can be appreciated through the thin medial wall of the orbit.

AFIFS is considered the most lethal form of fungal sinusitis, historically with mortality rates of 30–80%.3,14 More recent studies report mortality rates under 20% likely because of earlier recognition and treatment.15–17 Discrepancy exists as to whether the mortality rate in diabetic patients is higher than in non-diabetic patients.17,18 While some would argue that the reversible nature of the immunocompromised state of diabetic patients would lend to a more favorable outcome, it has been suggested that there is a greater prevalence of long-term complications and death in patients infected with Zygomycetes, the fungi class more prevalent in diabetics, compared to Aspergillus.19

Diagnosis of AFIFS is predicated on histopathologic confirmation of fungal invasion of the bone or the sinonasal tissue. However, the diseased tissue may not be accessible by a bedside biopsy. Imaging is thus critical in helping to establish the diagnosis and guiding surgical planning for biopsy and debridement.20 Treatment relies on a combination of antifungal therapy, surgical debridement of affected tissues, and reversal of immune status when possible.21 Infection with Aspergillus necessitates parenteral voriconazole; in mucormycosis, dual therapy with amphotericin B and caspofungin is the current antifungal standard of care,22 although some data support the use of posaconazole instead, especially in patients refractory or intolerant of treatment.23 Biopsy of the tissue is therefore critical to not only establishing the diagnosis but also directing appropriate therapy.20,24

One of the more difficult determinations in the management of AFIFS is whether there is orbital involvement that may necessitate exenteration. A recent study by Hargrove and colleagues outlined the difficulties surrounding the decision for exenteration.18 In light of this, the oculoplastic surgeon must understand the imaging characteristics of AFIFS in order to allow detection of the disease and help guide surgical debridement. A high index of suspicion is necessary, as early presentations are often subtle or attributed to less serious pathologies such as acute rhinosinusitis.3 It is recommended that immunocompromised patients with symptoms of sinusitis undergo early radiographic imaging.

Imaging of AFIFS

Due to the dire nature of the infection and the overlapping symptoms with common viral or bacterial rhinosinusitis, imaging is critical for early diagnosis of AFIFS and surgical planning. AFIFS is most commonly diagnosed and evaluated by computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MR). Osseous changes are best evaluated by CT; however, soft tissue changes are better delineated on MR. A recent study of immunocompromised patients with histopathologic confirmation of AFIFS found that MR was more sensitive and had a higher negative predictive value in detecting early changes of AFIFS, although the specificity and negative predictive value were equal to that of CT.25

AFIFS most commonly begins as mucosal inflammation around the middle turbinate. This initial site of infection may reflect why the middle turbinate is the most frequent positive biopsy site, accounting for two-thirds of the cases.20 It generally spreads to the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses, followed by the sphenoid sinus. The majority of patients with AFIFS have multiple sinuses affected, generally with only ipsilateral involvement. Posterior ethmoid air cells or sphenoid sinus involvement increases the likelihood of intracranial extension.17 CT characteristics of AFIFS include unilateral sinus opacification often with focal bone erosion, soft-tissue thickening of the sinuses and lateral nasal wall mucosa, and subtle infiltration of perimaxillary fat26,27 (Fig. 2). The fat infiltration may be secondary to edema from vascular congestion or fungal tissue infiltration.28 It can occur prior to bone destruction as the fungus spreads via perivascular channels.

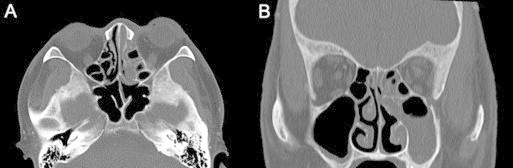

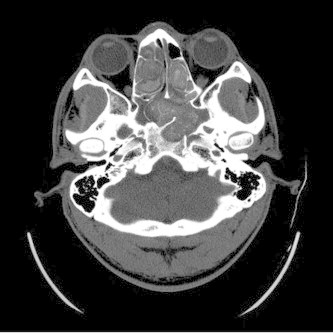

Figure 2.

Axial (A) and coronal (B) non-enhanced CT of AFIFS shows opacification of the left ethmoid, left maxillary sinus and left nasal cavity.

The bony erosion best identified on CT occurs comparatively late in the disease process and signifies extension beyond the sinus cavities.29 Hyperattenuation or hypoattenuation of the mucosal secretions is often seen, although hyperattenuation is more common in chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (CIFRS). The heterogeneous appearance of these fungal sinus secretions may be related to the presence of trace metals such as manganese, the elevated protein and decreased water content of the secretions, the presence of fungal hypha, or a combination of all of these features.30 Contrast administration to CT can better demonstrate changes in the periantral soft tissue and cause enhancement of adjacent extraocular muscles. Marked, unilateral nasal soft-tissue thickening is the most common early CT finding, although it is not specific to AFIFS.26 Changes that are more prominent such as retroantral fat pad inflammation, osseous erosion, and intracranial or orbital extension are more specific, but are late and less common features (Fig. 3). Intracranial abscesses, consisting of low density masses with little or no vasogenic edema, signs of leptomeningitis, and well-defined ring enhancement on CT have also been reported.31

Figure 3.

Axial non-enhanced CT of AFIFS demonstrates opacification of the left maxillary sinus with soft tissue inflammation of the premalar tissues (arrowhead) and of the retroantral fat (arrow).

MR findings include nonenhancing, hypointense turbinates (the “black turbinate sign”), sinus opacification, air–fluid concentration, obliteration of the nasopharyngeal planes, variable intensity within the sinuses on T1- and T2-weighted images (more likely hypointense on T2), loss of contrast enhancement (LoCE) of the sinonasal mucosa and extraocular muscles, inflammatory changes in the extraocular fat and muscles, and leptomeningeal enhancement29,32,33 (Fig. 4). The latter two are more common in advanced disease.25 Occasionally, as in the more chronic forms of invasive sinusitis, intracranial granulomas are also seen. These granulomas generally are hypointense on T1- and T2-weighted images without or with only minimal contrast enhancement.30

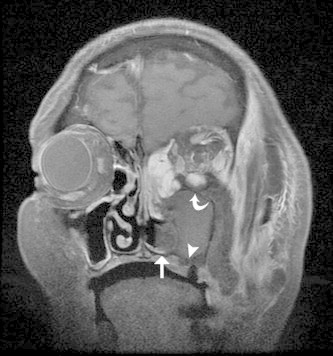

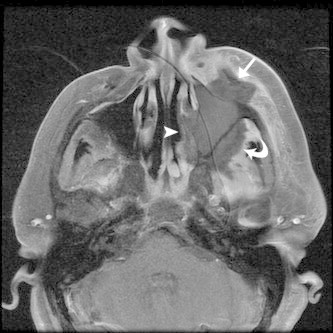

Figure 4.

Coronal T1 MR with gadolinium and fat suppression of AFIFS shows opacification of left maxillary and ethmoid sinuses with hypointense middle and inferior turbinates (straight arrow) and loss of contrast enhancement of the maxillary mucosa (arrowhead) and inferior rectus muscle (curved arrow).

More recent literature has concentrated on subtle early soft-tissue findings such as infiltration of the periantral fat and obliteration of nasopharyngeal tissue planes.32 Unfortunately, very early in the disease process, imaging findings are likely not distinguishable from those of common rhinosinusitis. The earliest findings that should raise suspicion for AFIFS are periantral fat infiltration, soft tissue stranding adjacent to the sinuses, and nasopharyngeal tissue plane obliteration8,34,35 (Fig. 5). On T1, infiltration of periantral fat will make this region isointense with unaffected surrounding soft tissue. Therefore, the fat pads adjacent to the maxillary sinus and its overlying subcutaneous fat should be carefully scrutinized for these subtle findings.

Figure 5.

Axial T1 MR with gadolinium and fat suppression of AFIFS demonstrates enhancement of the retroantral fat (arrow).

Given that AFIFS organisms have a strong tendency to proliferate along the blood vessels, it is not surprising that patients are at risk for signs of vasculopathy such as arteritis with aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, vasculitis, superior ophthalmic vein occlusion, cavernous sinus thrombosis, carotid dissection, arterial narrowing, basilar artery thrombosis, and other manifestations of infarction.35 The cavernous sinus portion of the internal carotid artery should be carefully scrutinized because it is especially at risk for damage. When the fungus extends intracranially, large vessel infarction with the associated CT and MR findings is observed, usually in the frontal lobes. Cavernous sinus thrombosis, heralded by severe headache, exophthalmos, vision loss, and involvement of cranial nerves II–VI is best evaluated by computed tomography venography (CTV) or magnetic resonance venography (MRV).

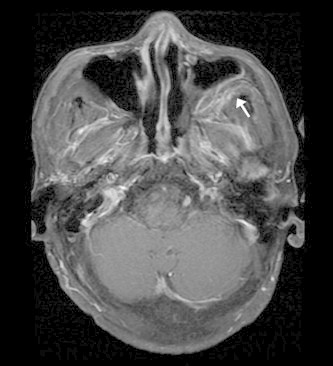

The other MR findings in AFIFS may also derive from ischemia via angioinvasion. From this vascular occlusion, the remaining vessels develop congestion, resulting in spillover edema, which may accentuate the soft tissue infiltration seen on MR. Loss of contrast enhancement (LoCE) of the sinonasal mucosa and rectus muscles may occur because infarction of the smaller blood vessels limits the spread of gadolinium25 (Figs. 4 and 6). This finding is best evaluated on T1 images. It has only been recently described in the setting of AFIFS and has not been reported in acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.25,36 Unaffected, healthy extraocular muscles and sinonasal mucosa enhance with gadolinium on T1 MR. Clinically, LoCE appears to correlate with devitalized tissue, which may be dusky or pale, or in the form of a black eschar.

Figure 6.

Axial T1 MR with gadolinium and fat suppression of AFIFS shows opacification of the left maxillary sinus with loss of contrast enhancement of the sinus wall, premalar tissues (straight arrow), retroantral fat (curved arrow) and of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity (arrowhead) which likely correlates to tissue necrosis.

To summarize the imaging evaluation for AFIFS, evidence of extrasinus infiltration suggests an invasive form of sinusitis. MR should be performed to evaluate intracranial and cavernous sinus involvement. MR is superior to CT in delineating soft-tissue contrast resolution, and it may therefore better demonstrate the subtle early findings of fulminant fungal invasion. When there is clinical suspicion of AFIFS in immunocompromised patients, careful attention should be paid to the retromaxillary and premalar fat, as any infiltration of this fat is concerning for AFIFS and may occur before osseous destruction.

Differential diagnoses based on imaging for AFIFS

The non-fungal differential diagnosis of AFIFS includes complicated acute and chronic viral or bacterial rhinosinusitis, granulomatosis with polyangitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis), and malignancies, most commonly sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma, and sinonasal non-Hodgkin lymphoma.37 The overlapping features of these diseases are that of sinonasal, mass-like, soft tissue involvement with variable amounts of bony erosion. Compared to AFIFS, granulomatosis with polyangitis causes more evidence of bony erosion and less mass-like soft tissue involvement37 (Fig. 7). The nasal cavity is generally most prominently involved, often with septal perforation, although orbit and skull base involvement is possible.

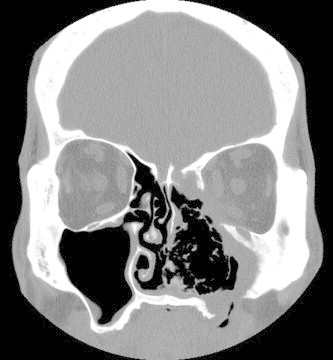

Figure 7.

Coronal non-enhanced CT of granulomatosis with polyangitis demonstrates a homogenous soft tissue mass extending into the left orbit with erosive changes of the left nasal cavity, ethmoid and maxillary sinuses resulting in septal perforation and bony erosion of the maxilla.

Sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma occur in immunocompetent patients and demonstrate a solid mass with osseous destruction. In squamous cell carcinoma, the mass is more solid-appearing with less adjacent soft tissue involvement compared to AFIFS (Fig. 8). Additionally, the maxillary antrum is more commonly involved in squamous cell carcinoma. The soft tissue mass in sinonasal non-Hodgkin lymphoma demonstrates T2 hypointensity, which also can occur in AFIFS. In lymphoma, this T2 hypointensity is likely secondary to the high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio of this malignancy38; however, soft tissue involvement is less prominent and the mass is more homogenous compared to AFIFS. As a rule of thumb, AFIFS can have more diseased tissue outside the sinuses than within them, and this finding is not present in paranasal sinus malignancies.39

Figure 8.

Coronal T2 MR of sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma shows a large mass involving the nasal cavity, bilateral ethmoid sinuses and left maxillary sinus with infiltration into the left orbit.

Complicated acute rhinosinusitis is more commonly of viral etiology than bacterial. In comparison to AFIFS, it is less likely to occur in the setting of immunocompromise or to have an odontogenic etiology, with less soft tissue involvement and bone erosion.40 Imaging findings can include air fluid levels, bubbly secretions, secretions of varying densities depending on composition, and mucosal thickening that can occlude the osteomeatal complex.36 The sinuses may also be opacified as in AFIFS; however, sinus involvement is more likely bilateral and the heterogeneity of secretions in non-fungal secretions is less distinct.40

In addition, bone thickening and sclerosis of sinus bones occurs more commonly in chronic viral or bacterial rhinosinusitis. Occasionally, it also occurs in allergic fungal rhinosinusitis, however, this is often accompanied by sinus expansion.39 In chronic viral or bacterial rhinosinusitis, the sinuses are of normal size and sometimes decreased in volume, demonstrating concave wall deformities secondary to osteosclerosis.41 LoCE has never been described in complicated rhinosinusitis, and instead, inflamed mucosa will enhance if contrast is administered.25,42 Despite these differences, the suspicion for AFIFS must be raised in at-risk patients and repeated imaging may be necessary to help establish the diagnosis.

Chronic forms of invasive fungal rhinosinusitis

All forms of invasive fungal rhinosinusitis are characterized by fungal invasion of blood vessels, mucosa, submucosa, and sinus walls. In comparison to the rapid onset of AFIFS, the chronic forms of invasive sinusitis occur over several months. Granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (GIFRS) presents with an enlarging mass in the cheek, orbit, nose, or paranasal sinuses, and generally occurs in immunocompetent hosts.43 The presenting feature is often proptosis. On histology, a noncaseating granulomatous reaction with considerable perivascular fibrosis and scant hyphal elements is seen.43 Aspergillus flavus is the most commonly isolated agent, and the presence or absence of precipitating antibodies against A. flavus correlates with disease progression.44 The disease has primarily been seen in Sudan, India, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia.24

Chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (CIFRS) is a slowly destructive process that most commonly affects the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses, but may involve any sinus. Patients are often elderly and mildly immunosuppressed, and endure symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis such as sinus pain, nasal discharge, low-grade fever, and intermittent epistaxis.39 Tenderness overlying a maxillary sinus with accompanying skin erythema is often observed on physical exam. CIFRS can be recurrent and persistent. Untreated patients are at risk for complications including visual changes, orbital apex syndrome from orbital invasion, and neurologic sequelae from central nervous system involvement.45 As seen in AFIFS, palatal erosions can develop from direct extension from the maxillary sinuses.

Aspergillus fumigatus is the most common pathogen isolated with greater than 50% culture-positive tissue.46 The other causative agents include the same organisms that cause AFIFS, as well as dematiaceous molds such as Bipolaris, Curvularia, Alternaria, and Pseudallescheria. Some authors believe that CIFRS has a more dense accumulation of hypha and a more sparse inflammatory reaction compared to GIFRS while others consider CIFRS to fall on a spectrum with GIFRS.2,47 The prognosis and therapy are currently the same, comprising the removal of affected tissue and systemic antifungals,47 although treatments will likely change as more is learned about these entities. In addition, a pseudotumor-like syndrome has been described in CIFRS patients who were erroneously placed on steroid therapy.47

The literature on imaging findings in CIFRS and GIFRS is limited, and the radiographic differences between these two entities are also unclear. No distinct imaging features have been reported for chronic/granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis; they are described as similar to AFIFS, to the non-invasive forms of fungal sinusitis, or as a combination of both48 (Fig. 9). Case reports have also described imaging findings indistinguishable from a malignancy with invasion of orbital soft tissue, sinuses, and skull base.47,49

Figure 9.

Axial CT with contrast of granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis demonstrating opacification of the ethmoid sinuses and fat stranding of the intraconal space of the right orbital apex.

In one case series of 17 patients at a tertiary hospital in India, chronic and granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis were grouped together. Radiographic features included unilateral involvement of one or two sinuses only, homogenous contrast enhancement on CT, lack of sinus expansion, bone erosion localized to the area of extra-sinus extension, and greater extrasinus versus intrasinus involvement.39 Others have described a soft tissue mass on CT in CIFRS as hyper-attenuating with destruction of the sinus walls and invasion outside of the sinuses.50 Invasion of surrounding structures as seen in AFIFS has been described with the development of abscesses in the epidural space or brain parenchyma, leptomeningitis, stroke, cavernous sinus thrombosis, osteomyelitis, mycotic aneurysm, and hematogenous dissemination.30

Non-invasive fungal sinusitis

The noninvasive forms of fungal sinusitis – the allergic and fungus ball forms – are defined by the absence of hypha within the sinonasal mucosa. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis (AFRS) is likely the most prevalent form of fungal sinusitis.51 It occurs in younger, healthier individuals as compared to the other forms of fungal sinusitis. Patients often endure years of nasal congestion, chronic headaches, and other symptoms of chronic sinusitis. The development of AFRS is more common in warm, humid climates where fungal species are more predominant.2

Patients are often atopic with conditions like asthma and eczema and may be observed to have eosinophilia and elevated total fungus-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) concentrations.52 AFRS represents a hypersensitivity to the dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi, including Bipolaris, Curvularia, Alternaria, or the hyaline molds such as Aspergillus and Fusarium.52,53 Accumulation of viscous eosinophilic mucin causes obstruction of sinus outflow tracts, allowing inflammatory mediators to cause gradual sinus expansion and bony erosion.54 Although the condition is not considered invasive, when untreated the sinus expansion and bony erosion can rarely lead to intracranial or orbital extension with the dramatic presentation of acute visual loss or gross facial dysmorphia.55 Treatment involves restoration of the normal sinus drainage, extirpation of the allergic mucin, and long-term nasal steroids to prevent recurrence. Additionally, antifungals have not been proven to be beneficial in treatment.56

AFRS is best delineated on noncontrast axial CT with coronal reformats. There is often pansinusitis or bilateral involvement of multiple sinuses, with ethmoid involvement being the most common8 (Fig. 10). On noncontrast CT, allergic mucin causes hyperintensity and near-complete opacification of the sinus lumens, whose mucosal linings are hypodense. With contrast administration, lack of enhancement in the center or in majority of the sinus helps distinguish AFRS from malignant tumors.41 Evidence of sinus expansion and osseous remodeling is also commonly observed. MR is obtained when there is concern that the process extends into the cranium or orbit.57

Figure 10.

Axial CT of allergic fungal rhinosinusitis shows bilateral involvement of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses filled with hyperintense mucin and evidence of sinus expansion and bone erosion. (Courtesy of William Dillon, MD and Songling Liu, MD.)

A fungus ball, also referred to as a mycetoma, aspergilloma, or chronic noninvasive granuloma, is an uncommon form of fungal sinusitis found in older, largely immunocompetent population. Interestingly, in contrast to the other forms of fungal rhinosinusitis, which are more common in males, the fungus ball is more prevalent in females.58 The putative cause is an inadequate mucociliary clearance system in which fungal organisms are not cleared from one of the sinuses distal to a site of obstruction; this may occur after radiation treatment, sinus surgery, or trauma.59 Patients may be asymptomatic or have minor chronic sinusitis symptoms such as nasal discharge, cacosmia, or chronic pressure over one sinus.59 Except in cases of extreme immunosuppression, the fungus does not invade blood vessels, bone, or sinonasal mucosa, although chronic nongranulomatous inflammation may be observed in the mucosa. Fungus balls are usually secondary to A. fumigatus; however, other fungi such as Pseudallescheria boydii and Alternaria have also been described as the etiologic agent.60

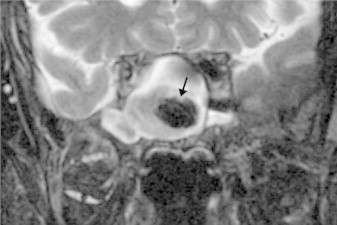

CT often demonstrates the involvement of only one sinus with a hyperintense (“metal-dense”) spot at the center of the fungus ball, often with sclerosis of the adjacent bone.14 It may be ovoid in shape or assume the contour of the sinus lumen. The fungus ball demonstrates low signal on both T1 and T2-weighted MR secondary to a lack of free water59 (Fig. 11). Non-enhanced CT is often considered the study of choice because intralesional calcifications are also often seen.61 Fungus balls are a surgical entity; antifungals and glucocorticoids are ineffective, and recurrence after removal is infrequent.1

Figure 11.

Coronal T2 MR of a fungus ball of the sphenoid sinus demonstrates low signal intensity (arrow). (Courtesy of William Dillon, MD and Songling Liu, MD.)

Conclusion

Fungal rhinosinusitis can be noninvasive or invasive. The different forms of fungal sinusitis can present with overlapping features. However, because of different pathophysiology and host immune response, specific imaging findings can be appreciated. Of the invasive forms, acute fulminant invasive fungal sinusitis is an especially important clinical entity to the oculoplastic surgeon because early intervention can be life-saving. Chronic invasive fungal sinusitis and chronic granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis develop over a prolonged time course although they can have extensive involvement as with AFIFS. Head and neck malignancies can have similar imaging findings and must be kept in consideration as well.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Nicolai P., Lombardi D., Tomenzoli D. Fungus ball of the paranasal sinuses: experience in 160 patients treated with endoscopic surgery. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(11):2275–2279. doi: 10.1002/lary.20578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakrabarti A., Denning D.W., Ferguson B.J. Fungal rhinosinusitis: a categorization and definitional schema addressing current controversies. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(9):1809–1818. doi: 10.1002/lary.20520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spellberg B., Edwards J., Jr., Ibrahim A. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:556–569. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.556-569.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazarika P., Ravikumar V., Nayak R.G., Rao P.S., Shivananda P.G. Rhinocerebral mycosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 1984;63:464–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergstrom L., Hemenway W.G., Barnhart R.A. Rhinocerebral and otologic mucormycosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1970;79:70–81. doi: 10.1177/000348947007900107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugar A.M. Mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14(Suppl. 1):126–129. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.supplement_1.s126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillespie M.B., O’Malley B.W., Jr., Francis H.W. An approach to fulminant invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in the immunocompromised host. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124(5):520–526. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.5.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adelson R.T., Marple B.F. Fungal rhinosinusitis: state-of-art diagnosis and treatment. J Otolaryngol. 2005;34(Suppl. 1):S18–S23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pillsbury H.C., Fischer N.D. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1977;103:600–604. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1977.00780270068011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leitner C., Hoffmann J., Zerfowski M., Reinert S. Mucormycosis: necrotizing soft tissue lesion of the face. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(11):1354–1358. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones A.C., Bentsen T.Y., Fredman P.D. Mucormycosis of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75:455–460. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Straatsma B.R., Zimmerman L.E., Gass J.D.M. Phycomycosis: a clinicopathologic study of fifty-one cases. Lab Invest. 1962;11:963–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Libshitz H.I., Pagani J.J. Aspergillosis and mucormycosis: two types of opportunistic fungal pneumonia. Radiology. 1981;140(2):301–306. doi: 10.1148/radiology.140.2.7019958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waitzman A.A., Birt B.D. Fungal sinusitis. J Otolaryngol. 1994;23(4):244–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parikh S.L., Venkatraman G., DelGaudio J.M. Invasive fungal sinusitis: a 15-year review from a single institution. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18(2):75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DelGaudio J.M., Clemson L.A. An early detection protocol for invasive fungal sinusitis in neutropenic patients successfully reduces extent of disease at presentation and long term morbidity. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(1):180–183. doi: 10.1002/lary.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathur S., Karimi A., Mafee M.F. Acute optic nerve infarction demonstrated by diffusion-weighted imaging in a case of rhinocerebral mucormycosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:489–490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hargrove R.N., Wesley R.E., Klippenstein K.A., Fleming J.C., Haik B.G. Indications for orbital exenteration in mucormycosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22(4):286–291. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000225418.50441.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingley A.P., Parkihh S.L., Delgaudio J.M. Orbital and cranial nerve presentations and sequelae are hallmarks of invasive fungal sinusitis caused by Mucor in contrast to Aspergillus. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22(2):155–158. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillespie M.B., Huchton D.M., O’Malley B.W. Role of middle turbinate biopsy in the diagnosis of fulminant invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2000;100(11):1832–1836. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200011000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yohai R.A., Bullock J.D., Aziz A.A., Markert R.J. Survival factors in rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1994;39(1):3–22. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed C., Bryant R., Ibrahim A.S., Edwards J., Jr., Filler S.G., Goldberg R. Combination of polyene-caspofungin treatment of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(3):364–371. doi: 10.1086/589857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh T.J., Raad I., Patterson T.F. Treatment of invasive aspergillosis with posaconazole in patients who are refractory or intolerant to conventional therapy: an externally controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(1):2–12. doi: 10.1086/508774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.deShazo R.D., O’Brien M., Chapin K., Soto-Aguilar M., Gardner L., Swain R. A new classification and diagnostic criteria for invasive fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123(11):1181–1188. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900110031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groppo E.R., El-Sayed I.H., Aiken A.H., Glastonbury C.M. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of acute invasive fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(10):1005–1010. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DelGaudio J.M., Swain R.E., Jr., Kingdom T.T., Muller S., Hudgins P.A. Computed tomographic findings in patients with invasive fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(2):236–240. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Addlestone R.B., Baylin G.J. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Radiology. 1975;115(1):113–117. doi: 10.1148/115.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gamba J.L., Woodruff W.W., Djang W.T., Yeates A.E. Craniofacial mucormycosis: assessment with CT. Radiology. 1986;160(1):207–212. doi: 10.1148/radiology.160.1.3715034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howells R.C., Ramadan H.H. Usefulness of computed tomography and magnetic resonance in fulminant invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 2001;15(4):255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aribandi M., McCoy V.A., Bazan C. Imaging features of invasive and noninvasive fungal sinusitis. Radiographics. 2007;27(5):1283–1296. doi: 10.1148/rg.275065189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bazan C., 3rd, Rinaldi M.G., Rauch R.R., Jinkins J.R. Fungal infections of the brain. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 1991;1:57–88. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silverman C.S., Mancuso A.A. Periantral soft-tissue infiltration and its relevance to the early detection of invasive fungal sinusitis: CT and MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(2):321–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safder S., Carpenter J.S., Roberts T.D., Bailey N. The “Black Turbinate” sign: an early MR imaging finding of nasal mucormycosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(4):771–774. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edelman R.R., Hesselink J.R., Zlatkin M.B. Paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity. In: Edelman R.R., Hesselink J.R., Zlatkin M.B., editors. 3rd ed. vol. 4. WB Saunders; New York: 2006. (Clinical magnetic resonance imaging). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terk M.R., Underwood D.J., Zee C.S., Colletti P.M. MR imaging in rhinocerebral and intracranial mucormycosis with CT and pathologic correlation. Magn Reson Imaging. 1992;10(1):81–87. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(92)90376-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cure J.K., Michel M.A. Amirsys Statdx; 2012. Acute rhinosinusitis. Available from: http://www.amirsys.com/statdx/features.php [accessed 11.06.12] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michel M. Amirsys StatDx Premier; 2012. Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Available from: http://www.amirsys.com/statdx/features.php [accessed 18.06.12] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erdag N., Bhorade R.M., Alberic R.A. Primary lymphoma of the central nervous system. Typical and atypical CT and MR imaging appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(5):1319–1326. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.5.1761319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reddy C.E., Gupta A.K., Singh P., Mann S.B. Imaging of granulomatous and chronic invasive fungal sinusitis: comparison with allergic fungal sinusitis. Otolaryngology. 2001;143(3):294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mafee M.F., Tran B.H., Chapa A.R. Imaging of rhinosinusitis and its complications: plain film, CT, and MRI. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2006;30(3):165–186. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:30:3:165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mukherji S.K., Figueroa R.E., Ginsberg L.E. Allergic fungal sinusitis: CT findings. Radiology. 1998;207(2):417–422. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.2.9577490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michel M. Amirsys StatDx Premier; 2012. Chronic rhinosinusitis. Available from: http://www.amirsys.com/statdx/features.php [accessed 12.06.12] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veress B., Malik O.A., el-Tayeb A.A., el-Daoud S., Mahgoub E.S., el-Hassan A.M. Further observations on primary paranasal Aspergillus granuloma in the Sudan. A morphological study of 46 cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1973;2:765–772. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1973.22.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chakrabarti A., Sharma S.C., Chander J. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of paranasal sinus mycoses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:745–750. doi: 10.1177/019459988910700606.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milroy C.M., Blanshard J.D., Lucas S., Michaels L. Aspergillosis of the nose and paranasal sinuses. J Clin Pathol. 1989;42:123–127. doi: 10.1136/jcp.42.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.deShazo R.D., Chapin K., Swain R. Fungal sinusitis. N Eng J Med. 1997;337:254–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707243370407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stringer S.P., Ryan M.W. Chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000;33(2):375–387. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(00)80012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Momeni A.K., Roberts C.C., Chew F.S. Imaging of chronic and exotic sinonasal disease: review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:S35–S45. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.7031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarti E.J., Blaugrund S.M., Lin P.T., Camins M.B. Paranasal sinus disease with intracranial extension: aspergillosis versus malignancy. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:632–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferguson B.J. Mucormycosis of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000;33:349–365. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(00)80010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ponikau J.U., Sherris D.A., Kern E.B. The diagnosis and incidence of allergic fungal sinusitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:877–884. doi: 10.4065/74.9.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferguson B.J. Eosinophilic mucin rhinosinusitis: a distinct clinicopathological entity. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:799–813. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200005000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katzenstein A.A., Sole S.R., Greenberger P.A. Allergic Aspergillus sinusitis: a newly recognized form of sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983;72:82–93. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(83)90057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Honser S.M., Corey J.P. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: pathophysiology, epidemiology, and diagnosis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000;33:399–408. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(00)80014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manning S.C., Schaefer S.D., Close L.G., Vuitch F. Culture positive allergic fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1991;117:174–178. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870140062007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schubert M.S. Allergic fungal sinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2004;37(2):301–326. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6665(03)00152-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michel M. Amirsys StatDx Premier; 2012. Allergic fungal sinusitis. Available from: http://www.amirsys.com/statdx/features.php [accessed 07.06.12] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dufour X., Kauffmann-Lacroix C., Ferrie J.C., Goujon J.M., Rodier M.H., Klossek J.M. Paranasal sinus fungal ball epidemiology, clinical features and diagnosis. A retrospective analysis of 173 cases from a single center in France, 1989–2002. Med Mycol. 2006;44:61–67. doi: 10.1080/13693780500235728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grosjean P., Weber R. Fungus balls of the paranasal sinuses: a review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(5):461–470. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferguson B.J. Fungus balls of the paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2000;33(2):389–398. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(00)80013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robey A.B., O’Brien E.K., Richardson B.E., Baker J.J., Poage D.P. The changing face of paranasal sinus fungus balls. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2009;118(7):500–505. doi: 10.1177/000348940911800708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]