Abstract

Until now, ex vivo generation of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) mostly involved use of feeder cells of non-human origin. While they provided invaluable models to study hematopoiesis, in vivo engraftment of hESC-derived HSCs remains a challenging task. In this study, we used a novel coculture system comprised of human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) and peripheral blood CD14+ monocyte-derived macrophages to generate CD34+ cells from hESCs in vitro. Human ESC-derived CD34+ cells generated using this method expressed surface makers associated with adult human HSCs and up-regulated hematopoietic stem cell genes compared to human bone marrow-derived CD34+ cells. Finally, transplantation of purified hESC-derived CD34+ cells into the pre-immune fetal sheep, primed with transplantation of MSCs derived from the same hESC line, demonstrated multi-lineage hematopoietic activity with graft presence up to 16 weeks post-transplantation. This in vivo demonstration of engraftment and robust multi-lineage hematopoietic activity by hESC-derived CD34+ cells lends credence to the translational value and potential clinical utility of this novel differentiation and transplantation protocol.

Introduction

Human embryonic stem cells (hESC) have been proposed as a novel source of HSCs for transplantation purposes [1–4] as the inexhaustible propagation of hESC lines could provide an infinite supply of hESC-derived HSCs. One potential clinical application of such hESC-derived HSCs could be for induction of tolerance towards other differentiated cells derived from the same hESC donor cell line by achieving hematopoietic chimerism [5, 6]. Furthermore, it is postulated that hESC-derived HSCs are at a developmental stage closer to fetal HSCs [7]. Thus, they could, at least theoretically, confer additional biological benefit compared to other sources of HSCs, for the purpose of in utero HSC transplantation (IUHSCT) as a therapeutic strategy for the amelioration of congenital hematological and immunological disorders diagnosed early in gestation [8, 9].

In spite of numerous perceived benefits, inducing differentiation of hESC towards hematopoietic cells with a capacity for efficient engraftment and long-term multilineage hematopoietic activity in vivo remains a challenging goal [1]. In the case of mouse ESCs, HSCs with a capacity for homing and engrafting the bone marrow (BM) in lethally irradiated adult mice were generated by the induction of HoxB4 gene and these cells achieved engraftment levels of 5–32% in the BM which could be of significance in the clinical setting [10]. However, compared to mouse ESC-derived HSCs, the progress with HSCs derived from hESCs has been lagging despite the advances made by several groups [11, 12]. For example, only low level engraftment of hESC-HSCs compared to that observed with mouse ESC-HSCs has been achieved [13, 14]. Woods et al. reported generation of up to 84% hematopoietic cells in vitro from hESCs but even in this case the level of in vivo engraftment left much to be desired [15].

Based on our recent findings on specific characteristics of macrophages upon their interactions with mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) [16, 17], and also work of other groups implicating macrophages as a major player in bone marrow microenvironment [18, 19], we hypothesized that co-culture of MSCs with macrophages could recapitulate a microenvironment in vitro reminiscent of the BM niche and thus promote hematopoiesis from hESCs. Also, in an effort to develop clinically applicable methods, we developed a culture method for expansion of hESCs free of matrigel, a matrix of murine sarcoma tumor origin. The results show that hESCs differentiated on human MSC-macrophage coculture system generate CD34+ cells with surface marker phenotype and gene expression profile similar to the adult human HSCs. Most importantly, these cells achieved engraftment in fetal sheep recipients at a level higher than previously reported and exhibited multi-lineage differentiation.

Materials and methods

Derivation of MSCs and macrophages

Human bone marrow (BM) MSCs were obtained from BM filters discarded at the end of bone marrow harvest from healthy donors according to University of Wisconsin-Madison IRB approved protocol as described previously [16]. MSC culture media was prepared by supplementing alpha minimum essential media (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), 1% non-essential amino acid (NEAA) and 2mM L-alanine-L-glutamine (Mediatech). Cells between passage 4 and 6 were used in the experiments. To obtain hESC-derived MSCs, cells were derived from hESCs using a protocol described previously and used at passage 4–6 [20]. Macrophages were generated by plating CD14+ monocytes isolated from peripheral blood (PB) buffy coats (Interstate Blood Bank, Memphis, TN, USA) using AutoMACS Pro Separation System (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). CD14+ cells were cultured using media comprised of IMDM basal media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% human serum type AB (PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria), 4µg/ml human insulin zinc (Invitrogen), 1% NEAA, 2uM L-alanine-L-glutamine and 1mM sodium pyruvate for 1 week in 6-well cell culture plate at 1 × 106 per well density.

Adult CD34+ cell proliferation assay

Adult human CD34+ cells were isolated by autoMACS pro cell separator using anti CD34 microbead (Miltenyi Biotec) from G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood (PB) apheresis product purchased from AllCells (Emeryville, CA, USA). Cells were stained with 10µM of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) for 15 min at 37 C, washed twice in PBS containing 0.5% human serum albumin, and then added to each well of a 6-well plate at 5 × 105 cells per well in 2ml of RPMI1640 basal media supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% NEAA, and 2mM L-alanine-l-glutamine. In groups with MSCs, 1 × 105 MSCs were used per each well, and 1 × 106 macrophages was used for conditions with macrophages. Cells were cultured for five days and then harvested for flow cytometry. Data acquisition and analyses was performed with Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and the ModFit Software Program (Verity Software, Topsham, ME, USA).

Differentiation of hESC into CD34+ cells

Human ESCs were added to BM-derived MSCs treated with 10 µg/ml mitomycin C for two hours. Differentiation media was prepared by supplementing alpha MEM basal media with 20% FBS, 1% NEAA, 2 µM L-Alanine-L-Glutamine and 200 mM 1-thioglycerol. Freshly isolated CD14+ cells from peripheral blood buffy coats were then added to hESC/MSC cocultures described above at a density of 1 × 106 per well. Alternatively, macrophages were generated by plating CD14+ cells for 1 week in macrophage culture media as described above and then Mitomycin C treated MSCs were added at 2 × 105 per well. After culturing at least for one day to allow attachment of MSCs, hESCs were added for coculture. Both methods generated similar level of CD34+ cells. Final volume of media for coculture was 5 ml per well in 6-well plates, and culture was maintained in 37 °C, 5% O2 and 5% CO2 condition which were generated by nitrogen purging methods. Media was changed every three to four days by half media change and supplemented with 1-thioglycerol every two to three days. Differentiated cells were harvested on days 9, 11, 14, and 16 for initial evaluations and then on day 11 for the rest of the studies.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay

Human ESC-derived CD34+ cells (n=5) were isolated from coculture on day 11 using magnetic bead based separation method. CD34 microbeads were used to positively select CD34+ cells after depleting CD14+ and CD73+ cells. For comparison, CD34+ cells isolated from BM (n=6) were used. For principal component analysis, data from undifferentiated hESCs (n=4), hESC-derived CD34+ (n=5), BM CD34+ (n=2), and G-CSF mobilized PB CD34+ cells (PB CD34+, n=3) were used. Principal component analysis was performed to aid in visualizing multidimensional data and statistical package PAST was used for this purpose. Principal component analysis aims to capture variations present in high-dimensional data with small set of coordinates and has been used as an invaluable tool in gene expression analysis [21, 22].

For generation of BM CD14+ cell-derived macrophages and, CD14+ cells were isolated from BM aspirates of normal donors (AllCells) and harvested after 1 week (n=6). For generation of MSC educated macrophages (n=6), CD14+ cells from PB were cultured for 1 week and MSCs was added for additional 3 days before macrophages were sorted by CD14 microbead based separation. Additionally, PB CD14+ monocyte derived macrophages (n=3) were used as controls.

RNA was isolated from cells using RNeasy micro kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and the quality of isolated RNA was checked using Epoch microplate reader and Take3 microvolume plate (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT, USA). RNA was converted to cDNA using Quantitect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed using Power SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on StepOne Plus instrument (Applied Biosystems) using standard protocol. Verified primers were purchased from Qiagen. Threshold cycle (Ct) value for each gene was normalized by the average Ct number of three housekeeping genes (RN18S1, GAPDH and ACTB).

Fetal Sheep transplantation

Fetal sheep transplantations were carried out at the University of Nevada-Reno Agriculture Experimental Station based on a protocol approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Donor stem cells were injected into the liver of the fetus in 1.0 ml of QBSF60 serum-free media (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA, USA); adequacy of injection was confirmed by ultrasound-visualized accumulation in the peritoneal cavity [23]. To confirm the homing and engraftment of human hematopoietic cells in the BM of transplanted sheep, bone sections were double-stained with anti-CD45 antibody (ENZO lifesciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) which stains both human and sheep cells, and with anti-human nuclei antibody to specifically detect human cells, according to standard histology protocols for paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Multi-lineage differentiation of human HSCs in the PB of sheep was detected by flow cytometry of sheep PB samples, using human-specific CD45 antibody or other human-specific antibodies (BD Bioscience) as described previously [24].

Two sets of experimental groups were utilized for testing engraftment of hESC-derived CD34+ cells. The first group (animals 2716, 2724 and 2725) received 2 × 106 passage 5 MSCs derived from hESCs on gestation day 55, followed by the transplantation of 3 × 105 hESC-derived CD34+ cells at day 61, and analyzed at term of 147 days for human CD45 engraftment in the peripheral blood against non-transplanted control animal using human-specific anti-CD45 antibody (Supplemental Table 1). In the second group, six animals were injected with 2 × 106 hESC-derived MSCs at day 60 of gestation; at day 66, animals received Plerixafor (Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) at 5 mg/kg about 5 minutes prior to CD34+ cell transplantation and then three animals (2786, 2787 and 2788) received 3 × 105 hESC-derived CD34+ cells, two animals (2791 and 2792) received 2.8 × 105 cord blood-derived CD34+ cells, and one (2777) that did not receive any CD34+ cells served as control (Table 1). The cord blood units used for obtaining CD34+ cells using CD34+ microbeads were units collected and discarded due to insufficient volume at Duke University Medical Center in accordance with their IRB. Transplanted animals were analyzed at 10 weeks post-transplantation.

Table 1. Comparison of HSCs source and engraftment levels in the sheep model.

CD34+ cells were differentiated from the hESC for the first group (# 2786, 2787 and 2788), and isolated from CB for the second group (# 2791 and 2792). One animal (# 2777) was transplanted with MSC only and used as a control. The percentage of total human hematopoietic cells in PB was tallied from the multi-lineage analyses in Figure 4 (column 5). BM aspirates collected at 10 weeks post-transplantation were assayed for the formation of colonies (White colonies: CFU-GM, CFU-G and CFU-M, Mixed colonies: CFU-GEMM). The numbers of colonies with human genomic DNA, out of the total number of colonies with amplifiable DNA are presented (columns 6 and 7).

| Animal # | Surgery #1 (Day 60) |

Surgery #2 (Day 66) |

Human cells in PB (%) |

Average Human cells in PB (%) |

White Colonies (10 week post-TPL) |

Mixed Colonies (10 week post-TPL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2786 | 2 × 106 hESC-MSC |

3 × 105 hESC CD34+ |

6.14 | 6.82 | 0/0 | 1/3 |

| 2787 | 9.68 | 0/2 | 4/6 | |||

| 2788 | 4.65 | 4/5 | 11/13 | |||

| 2791 | 2.8 × 105 CB CD34+ |

1.73 | 1.74 | 0/0 | 0/0 | |

| 2792 | 1.75 | 0/0 | 7/8 | |||

| 2777 | None | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

Progenitor Assay on sheep bone marrow cells

Bone marrow aspirates (5 ml) were collected from transplanted sheep from the second group at 10 weeks post-transplantation. 5 × 105 cells were mixed with MethoCult H4434 media (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) and three 0.5 ml aliquots were added to 3 wells of a 4-well Nunc culture plate (1.25 × 105 cells per well). Plates were cultured for 10–14 days until defined colonies could be identified and counted. Individual colonies were plucked via aspiration and DNA was prepared from the cells using DNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer suggested protocol. qPCR was performed as described previously [24] using human microsatellite primers (left: 5’-ATT CAC GTC ACA AAC TGA ACA TTC-3’ and right: 5’- CGT TTG AAA TGT CCG TTT GTA GAT-3’) to identify human colonies, and RN18S1 primers (left: 5’-CAT TCG AAC GTC TGC CCT AT-3’ and right: 5’-GCC TTC CTT GGA TGT GGT AG-3’) to establish the presence of DNA in all samples.

Results

Comparison of BM monocyte derived macrophages with MSC-educated macrophages

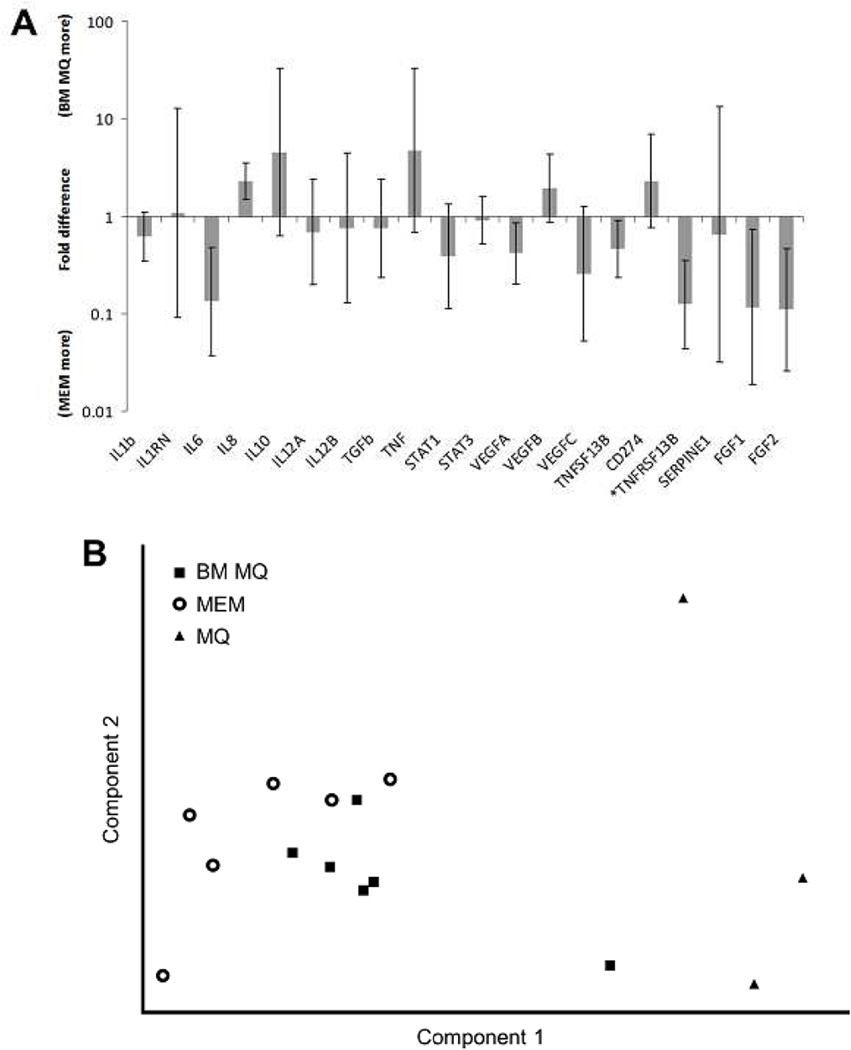

Several genes we previously reported to be differentially expressed between MSC-educated macrophages and control macrophages [17] were tested using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and the result is depicted in Figure 1A. Gene expression of MSC-educated macrophages (n=6) and BM monocyte derived macrophages (BM-derived macrophages n=6) did not differ in a statistically significant way except for TNFRSF13B when analyzed by t-test with cut off value of p=0.05. Principal component analysis was performed with MSC-educated macrophages, BM-derived macrophages, and PB monocyte derived macrophages (PB-derived macrophages, n=3). Two dimensional plots of first two components, which accounted for about 43% and 22% of total variation in the data respectively, are depicted in Figure 1B, which show clustering of MSC-educated macrophages and BM-derived macrophages away from PB- derived macrophages. VEGFC, bFGF, aFGF, IL1RN, PDL1, TNF and IL6 were among the genes that contributed most to component 1. This suggests that phenotype of MSC-educated macrophages is similar to BM- derived macrophages and distinct from PB-derived macrophages and thus supportive of our hypothesis to use MSC-educated macrophages in our ex vivo differentiation system.

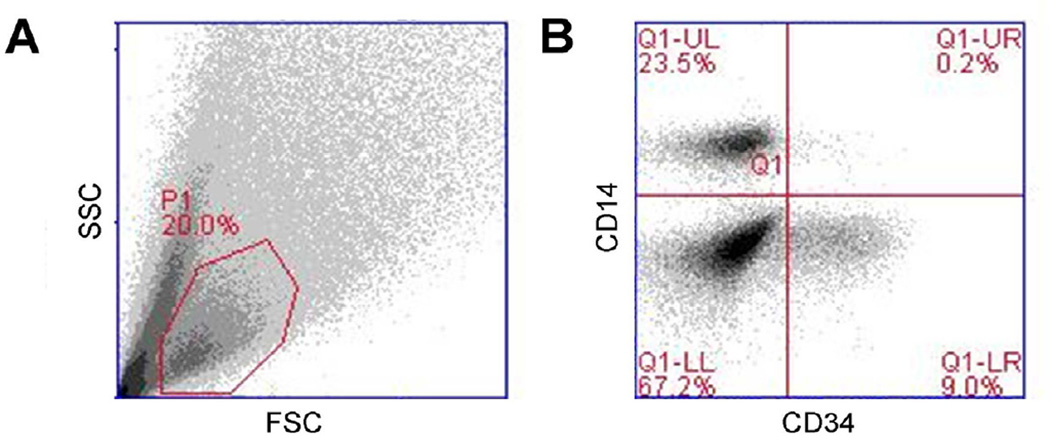

Figure 1. Combination of MSCs and macrophages simulates bone marrow microenvironment.

(A) The level of gene expression was not statistically different between MSC-educated macrophages (MEM) and bone marrow macrophages (BM MQ) in most of the genes tested except TNFRSF13B (p value <0.05), suggesting similarity between two population. (B) Principal component analysis on MEM, BM MQ samples with peripheral blood monocyte derived macrophages (MQ, n=3) shows clustering of MEM with BM MQ, away from MQ. (C) MSCs and macrophages were able to support proliferation of CD34+ cells and the combination of MSCs and macrophages increased proliferation of CD34+ cells more than either cell type alone.

Proliferation of CD34+ cells in coculture with MSCs and/or macrophages

In coculture experiments both MSCs and macrophages increased proliferation of CD34+ cells isolated from adult PB (n=3) in vitro (Figure 1C). When proliferation index was normalized against CD34+ cells controls (relative proliferation index (RPI) = 1.00), coculture with MSCs increased RPI to 1.70±0.09 and macrophages increased RPI to 2.42±0.11. The effect of MSCs and macrophages on the proliferation of CD34+ cells was more prominent when both cell types were present as RPI for this condition was 5.93±0.43. Assuming six pair wise comparison within four groups, we used Bonferroni correction with n=6. When compared to CD34+ cell only control, increased RPI observed in cocultures were statistically significant as following: MSCs (p value = 0.032), macrophages (p value = 0.013) and MSCs + macrophages (p value = 0.015). Coculturing CD34+ cells with macrophages alone increased their proliferation compared to MSC coculture (p value= 0.006), but coculturing with MSCs + macrophages induced more proliferation compared to MSC alone (p value = 0.001) and macrophage alone cocultures (p value = 0.001). These results show that combination of MSC and macrophages induce a statistically significant higher rate of proliferation of CD34+ cells compared to either cell type alone.

Culturing hESCs without matrigel using human serum based matrix

Matrigel is a protein mixture secreted from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma cell line [25] that has been extensively used for hESC culturing. In order to improve clinical applicability of our hESC differentiation protocol, we developed a hESC culture method replacing matrigel with a human serum based matrix which was able to support the attachment of hESCs while allowing expansion of hESCs without any morphological changes up to passage 20 (Figure S1A). Flow cytometry assay showed that the hESCs cultured on human serum based matrix retained expression of SSEA4, SSEA3, TRA 1–60, TRA 1–81 and Oct3/4, markers characteristics of undifferentiated hESCs, while expression of SSEA1, a marker of differentiated hESCs, remained low (Figure S1B). Finally, karyotyping results showed hESCs maintained for 15 passages on human serum based matrix to be free of clonal abnormality (Figure S1C), and teratoma formation verified the pluripotency of these hESCs (Figure S1D).

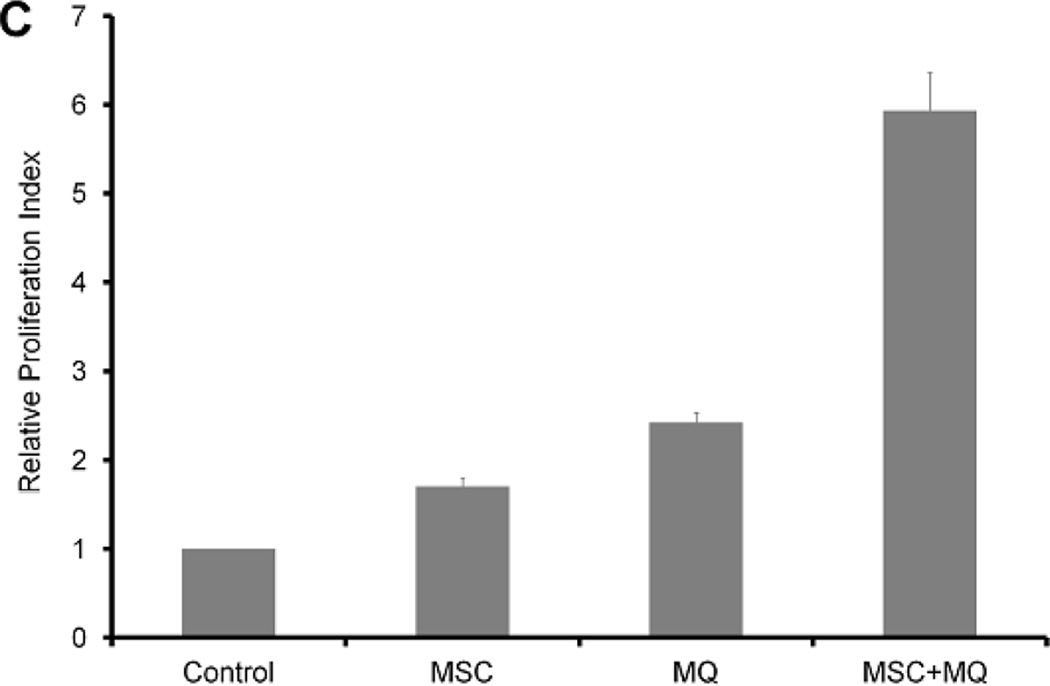

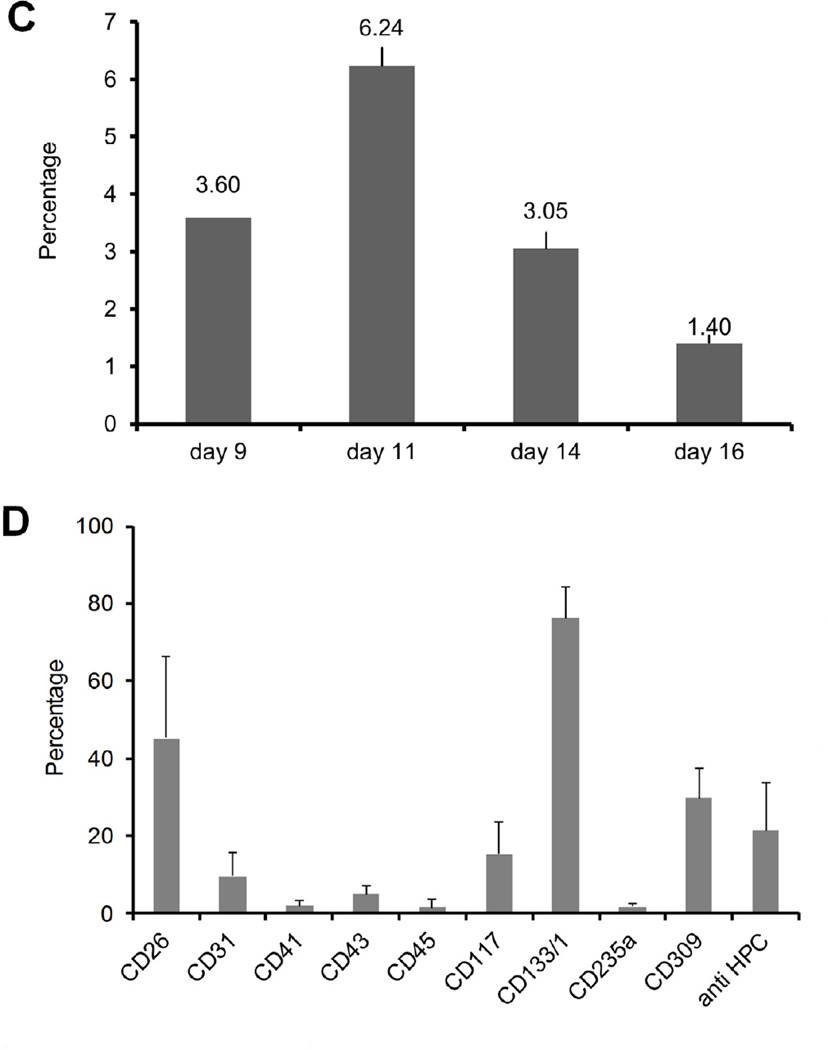

Generation of CD34+ cells from hESCs cocultured with MSCs and macrophages

We used flow cytometry to track generation of CD34+ cells from hESCs, cocultured with MSCs and macrophages. Gating strategy and representative results are depicted in Figure 2A–B. In cocultures of MSCs and CD14+ without hESCs, no CD34+ cells were detected (data not shown). The level of CD34+ cells reached its maximum around day 11 and decreased as the coculture progressed further (Figure 2C). Analysis of cell surface markers expressed by the CD34+ cells generated from hESCs was done by flow cytometry using antibodies against CD26, CD31, CD41, CD43, CD45, CD117 (c-kit), CD133/1, CD235a (Glycophorin A), CD309 (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2)) and anti HPC (Hematopoietic progenitor cell) antibody. These markers were chosen either because of their association with putative hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells or as markers for differentiated cells. The results demonstrate that CD34+ cells generated from hESC-MSC-Macrophage coculture system were positive for CD26 (42.70±18.04), CD117 (16.89±7.61), CD133/1 (75.81±6.99), CD309 (23.50±11.46) and anti HPC (22.76±10.26) (Figure 2D). Expression level of other markers remained below 10% and those values did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2. CD34+ cells generated from hESC-MSC-Macrophage coculture.

The gating strategy used for cocultured cells (A) and representative flow cytometry data (B). Among the live cell gating, about 20% of cells were CD14 positive macrophages while about 10% of cells stained positive for CD34 positive cells. (C) The percentage of CD34+ cells present vs. days in culture from one representative culture. The level of CD34 positive cells reached maximum around day 11 and subsequent culture exhibited decreased level of CD34 positive cells. (D) The cell surface marker expression of CD34+ cells differentiated from hESCs. CD26, CD117, CD133/1, CD309 and anti HPC antigen are expressed in a statistically significant way.

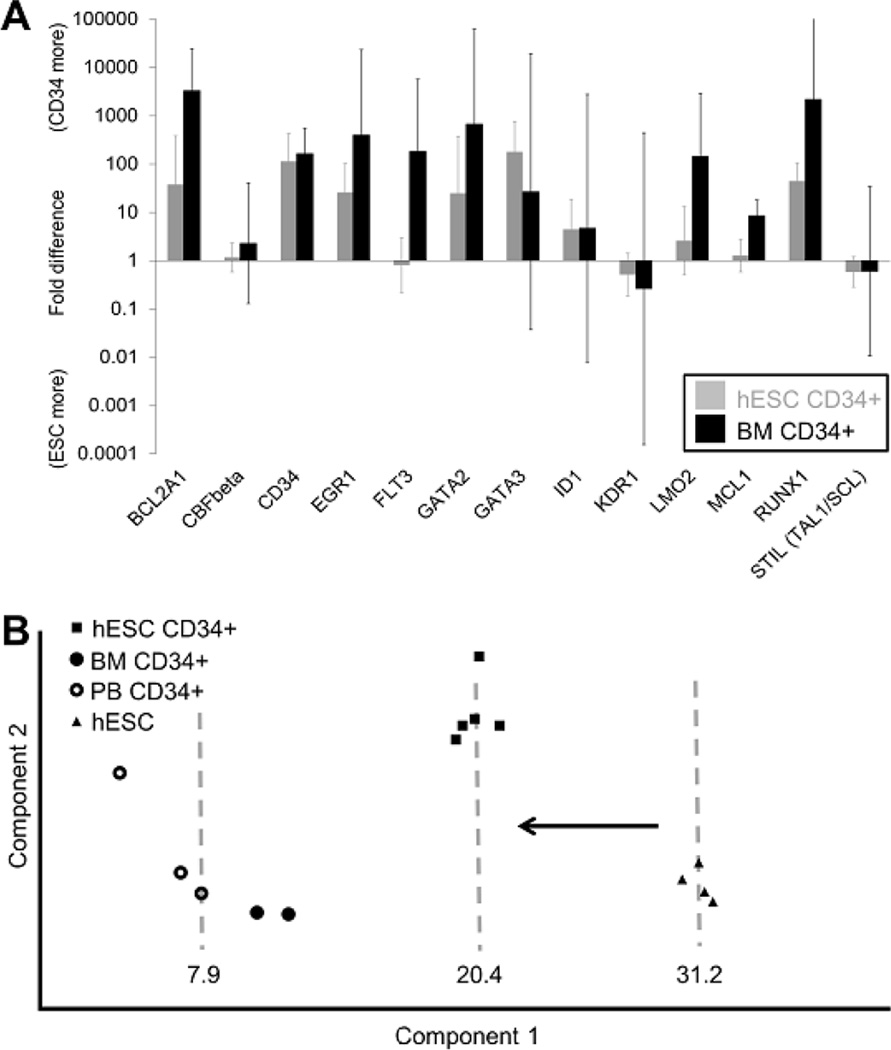

Genes associated with hematopoiesis are enriched in hESC-derived CD34+ cells

qPCR analysis was performed to study the expression level of selected genes associated with hematopoiesis and the result is summarized in Figure 3. The following is the list of genes up-regulated significantly in hESC-derived CD34+ cells compared to undifferentiated hESCs with their corresponding fold-increase and 95% confidence interval: BCL2A1, CD34, EGR1, GATA2, GATA3, ID1 and RUNX1. Higher level of expression of BCL2A1, CD34, EGR1, GATA2 and RUNX1 were common in both hESC-derived CD34+ cells and adult BM CD34+ cells (BM CD34+) compared to undifferentiated hESCs (Figure 3A). Principal component analysis using undifferentiated hESC, BM CD34+, G-CSF mobilized PB CD34+ cells (PB CD34+) and hESC-derived CD34+ cells revealed that hESC-derived CD34+ cells shifted along the principal component 1 toward BM CD34+ and PB CD34+ while away from undifferentiated hESCs (Figure 3B). Component 1 and 2 accounted for about 73% and 18% of total variation, respectively, with BCL2A1, KDR1, RUNX1 and CD34 contributing the most to component 1.

Figure 3. Comparison of gene expression of CD34+ cells from different origin.

The expression of 13 hematopoietic genes in were analyzed and then normalized to the average for 3 housekeeping genes (18S rRNA, GAPDH and b-Actin) for each sample. (A) BCL2A1, CD34, EGR1, GATA2 and RUNX1 were up-regulated compared to hESCs in both hESC-derived CD34+ cells (hESC CD34+, n=6) and bone marrow CD34+ (BM CD34+, n=6) with statistical significance (t-test, p value < 0.05). GATA3 and ID1 were up-regulated in hESC CD34+ while FLT3, LMO2 and MCL1 were up-regulated in BM CD34 compared to hESCs. (B) Principal component analysis using gene expression data from hESC (n=4), hESC-derived CD34+ (n=5), BM CD34+ (n=2) and mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells (PB CD34+, n=3). hESC CD34+ (Component 1 average value = 20.4) showed shift toward BM CD34+ and PB CD34+ (Combined component 1 average value = 7.9) away from hESCs (Component 1 average value = 31.2) along the principal component 1 which accounted for 72.8% of total variation within the data set.

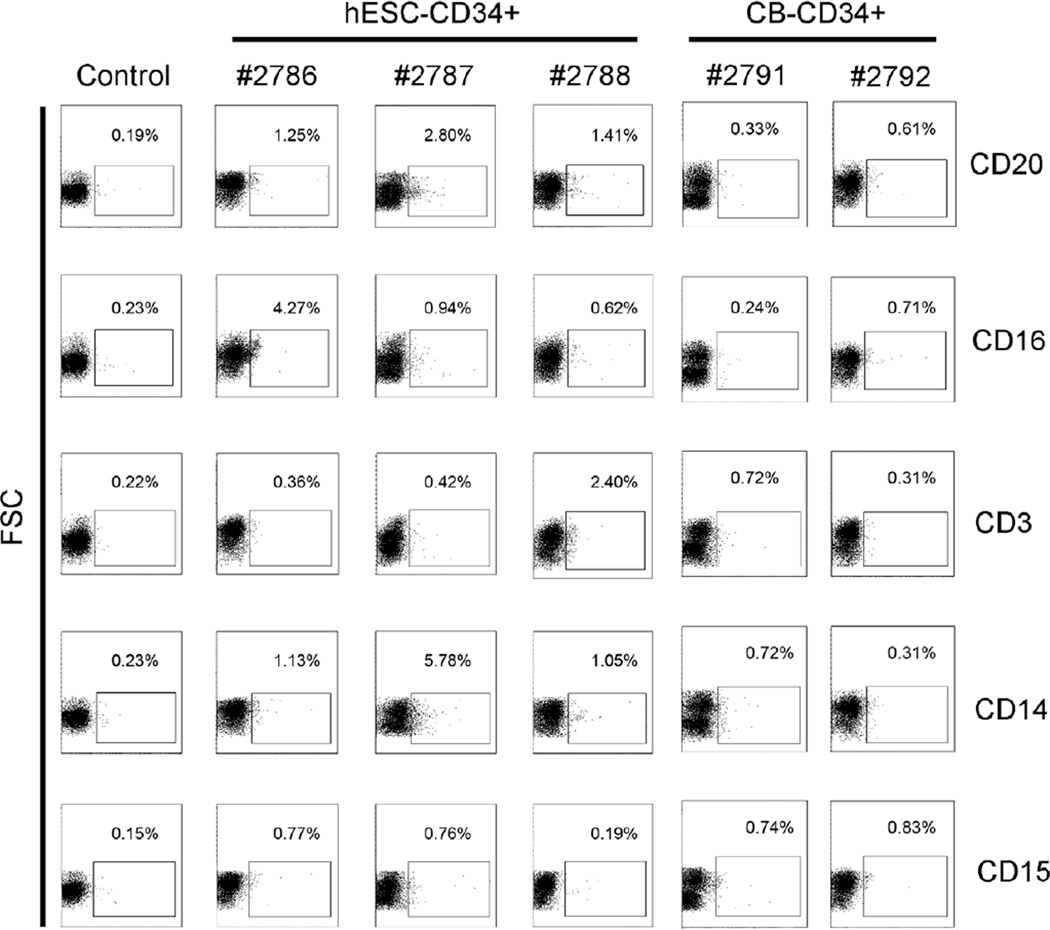

Engraftment of hESC-derived CD34+ cells in the fetal sheep model

First group of three animals injected with hESC derived CD34+ cells (animal 2716, 2724 and 2725) were tested for the presence of human CD45+ cells in the peripheral blood using human CD45+ specific antibody and flow cytometry at either 12 weeks or 16 weeks post-transplantation (after birth) and human origin cells were detected (Table S1, Figure S2). After this initial confirmation of long-term engraftment of hESC-CD34+ cells, the second group of sheep were tested earlier for multilineage differentiation of hESC derived CD34+ and compared with cord blood (CB) CD34+ cells. Peripheral blood harvested at 10 weeks post-transplantation demonstrated differentiation along the lymphoid lineage with B cells (CD20), NK cells (CD16), T cells (C3), and along the myeloid lineage with monocytes (CD14) and neutrophils (CD15) (Figure 4). Up to 9.86% multi-lineage human hematopoietic activity was observed in sheep transplanted with hESC-derived CD34+ cells (animal nos. 2786, 2787, and 2788) compared to about 1.75% in cord blood (CB) CD34+ cell recipients (animal nos. 2791 and 2792), and no human hematopoietic activity in the no CD34+ control injected with MSC only (animal no. 2777) (Table 1).

Figure 4. Engraftment of hESC-derived CD34+ cells in sheep after in-utero transplantation.

Flow cytometric analysis of in vivo multi-lineage differentiation potential of hESC-derived CD34+ cells in comparison to cord blood (CB)-CD34+ cells in peripheral blood after in-utero transplantation. The lymphoid lineage with B cells (CD20), T cells (CD3), NK cells (CD16), and the myeloid lineage with neutrophils (CD15) and monocytes (CD14) were analyzed from animals transplanted with hESC-derived CD34+ cells (# 2786, 2787, and 2788) and CB-CD34+ cells (# 2791 and 2792) at 10 weeks post-transplantation. Animal with no CD34+ transplantation was used as control.

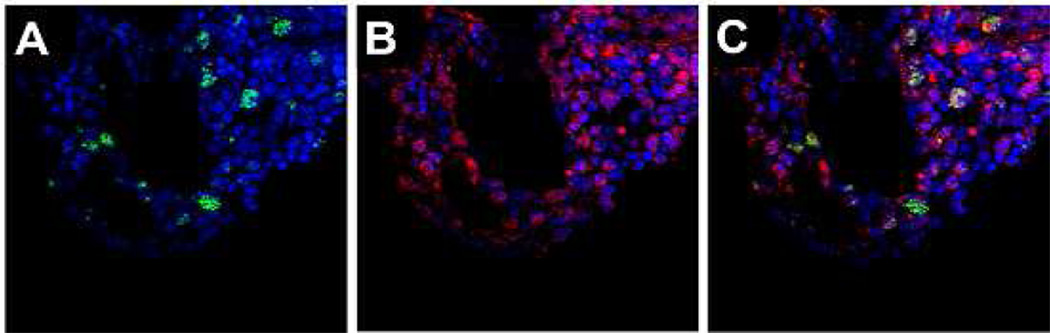

In vivo homing of hESC-derived CD34+ cells

To confirm the homing and engraftment of human hematopoietic cells in the BM of sheep transplanted with hESC-derived CD34+ cell at the time of birth, bone sections were double-stained with anti-CD45 antibody and with anti-human nuclei antibody specific to human cells and non-reactive to sheep. Whereas the anti-CD45 antibody used for flow cytometry was human-specific, that used for immunohistochemistry labeled both human and sheep cells, requiring the use of anti-human nuclei antibody to differentiated human from sheep CD45+ cells. Representative data from the BM of transplanted animal at 20 weeks post-transplantation is depicted in Figure 5 which shows that some of CD45 positive cells present in the sheep bone marrow is of human origin.

Figure 5. Cross sections of bone from animal transplanted with hESC-derived CD34+ cells.

Bone marrow of sheep transplanted with hESC-derived CD34+ cells were stained with anti-human nuclei antibody (green) and anti-CD45 antibody (red). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Microscope images are for the green and blue channels (A), red and blue channels (B), and tri-color (C). While most of the CD45+ cells are endogenous to the sheep, transplanted human cells which are dual positive for CD45 (red) and human nuclei (green) are evident. Dark area represents cross sections of blood vessels in the BM. Photomicrographs were taken on an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 confocal microscope with UPlanFLN 40×1.30 numeric aperture oil objective lens, using FV10-ASW version 01.05.00.14 software (Olympus America Inc., Melville, NY, USA). Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop, version CS5.

Presence of colony-forming cells in BM

The presence of progenitor cells in BM aspirates of fetal sheep transplanted with CD34+ cells (CB or hESC-derived) at 10 weeks post-transplantation was assayed by methyl cellulose colony formation assay. DNA was isolated from 51 colonies and 37 DNA preparations were amplifiable by PCR using the RN18S1 primers which amplify both human and sheep DNA. Human genomic DNA was detected using human microsatellite primers in 27 out of 37 colonies (Table 1). Four of the five animals presented mixed colonies signifying the presence of multi-lineage progenitor cells, and two animals presented a few white colonies. Since the media contained human specific recombinant human (rh) granulocyte monocyte colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and rh interleukin (IL)-3, it is likely that this media promoted the biased generation of human CFUs, explaining the limited number of sheep colonies observed.

Discussion

MSCs comprise a major component of the BM niche [26–31] and have been proven to be invaluable tools for investigating the stem cell niche in both normal and malignant hematopoiesis [32, 33]. However, the use of normal human BM-derived MSCs alone has not been enough to efficiently generate CD34+ cells from hESCs and stromal cells of the BM origin from various mouse strains such as OP9 or S17 have been used instead [34–36]. Also, although these models provide invaluable insight into the biology of hematopoiesis, they could not be easily translated into clinical application as the use of mouse feeder cell lines raises concerns for transmission of animal associated pathogens. Furthermore, for clinical utilization of these cells, development of methodologies to generate cells capable of robust engraftment in vivo with differentiation capability into different lineages is necessary [13–15].

Based on our recent findings on the interactions between MSCs and macrophages [16, 17], we hypothesized that combination of MSCs and macrophages could recapitulate the BM niche and support generation of HSCs from hESCs. Traditionally, macrophages were considered as negative regulators of HSCs [37] but recent findings regarding the role of macrophages in supporting HSCs suggest that macrophages might play an important role in the formation of niche for HSCs [19, 38, 39]. Specifically, we have shown that macrophages generated by co-culturing with MSCs [16] exhibit certain characteristics beneficial for supporting hematopoiesis. For example, interleukin (IL)-6 is a well-known cytokine effective in ex vivo expansion of the HSCs [40, 41] and IL-10 has also been shown to support expansion of the HSCs [42, 43]; both cytokines are upregulated in macrophages cocultured with MSCs (MSC-educated macrophages) [16]. We have recently shown, using qPCR analysis, that in patients with multiple myeloma, MSC-educated macrophages have a gene expression pattern similar to the BM CD14+ monocyte derived macrophages [17]. In this study we compared normal BM monocyte derived macrophages and MSC-educated macrophages (Figure 1A–B). The results confirm that culturing PB CD14+ derived macrophages with MSCs induces a gene expression pattern similar to normal BM monocyte derived macrophages. Moreover, macrophages in combination with MSCs support proliferation of the adult HSCs (Figure 1C), suggesting that macrophages cooperate with MSCs to recapitulate the HSC niche in vitro.

Based on these findings, a novel strategy was developed to generate CD34+ cells from hESCs using a combination of MSCs and macrophages as feeder cells. CD34+ cells generated from hESCs using this method expressed cell surface markers associated with hematopoiesis. Zambidis et al. reported that hemangioblast generated from hESCs expressed CD143 or angiotensin converting enzyme which is targeted by anti-HPC antibody [44]. Also, it has been reported that angiotensin converting enzyme is a marker for HSCs in human embryo [45]. Some of hESC derived CD34+ cells were positive for CD309, CD133 and CD117 (c-kit), markers traditionally associated with HSCs [46–49]. Yin et al. have reported that CD34+, CD133+ cells from adult BM could engraft fetal sheep model [50], the same model used in this study to test engraftment of cells. Moreover, gene expression results showed the up-regulation of several hematopoietic genes (BCL2A1, CD34, EGR1, GATA2 and RUNX1) in both hESC-derived CD34+ cells and adult BM CD34+ cells compared to undifferentiated hESCs.

To verify the engraftment potential of CD34+ cells generated from hESCs, we chose the fetal sheep xeno-transplantation model that has been used for more than two decades as an in vivo model for studying hematopoiesis [51, 52]. Some of the potential advantages of this model include its recapitulation of the physiological and developmental characteristics of the human fetus, making it a great model for intra-uterine hematopoietic cell transplantation (ref). and the capability for efficient and safe manipulation early in gestation [53]. Moreover, the relatively long life span and large size of these animals allows for the repeated and long term evaluation of donor cell activity and increased sensitivity for detection of engraftment [54]. To our knowledge this is also the first report on use of hESC-derived MSCs in priming the recipient bone marrow prior to transplantation of CD34+ cells derived from the same hESC line. Human ESC derived CD34+ cells generated by the protocol described in the current study engrafted at a higher level compared to the level previously observed with S17 coculture methods derived hESC-derived HSCs (<1%) [24]. Graft presence from hESC-derived HSCs followed up to 16 weeks post-transplantation (Table S1) further supports the engraftment of long term HSCs.

While the current studies demonstrate the capacity for long term engraftment and multi-lineage differentiation from hESC-derived CD34+ cells, there are limitations to this report. First, the method described herein does not rule out the possibility that combination of other cell types, such as vascular endothelial cells that are known to play a prominent role in the bone marrow niche complex [55], might perform better as a feeder layer for differentiating hESCs toward HSCs. Thus, further research efforts on designing more effective in vitro platforms for more efficient differentiation of hESCs is still warranted. Also, additional studies are necessary to find out the detailed mechanisms behind the role of MSC-macrophage combinations on directing differentiation of hESCs into hematopoietic cells. Elucidation of molecular pathways responsible for induction of HSCs could enable generation of HSCs without relying on such complex couture systems. Another shortcoming of our study is that we did not directly compare the level of engraftment of our hESC-derived CD34+ cells with CD34+ derived from hESCs using other technologies, but rather we compared it to a previously reported study using the same fetal sheep model [24]. Despite these limitations, the results described in the current study could serve as a basis for developing clinically applicable methods for generation of HSCs from hESCs. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report demonstrating promising levels of in vivo engraftment of hESC-derived CD34+ measured up to 16 weeks post-transplantation, and with multi-lineage activity data in comparison to CB CD34+ cells at 10 weeks post-transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tenneille Ludwig and Jenny Brehm (WiCell Research Institute) for testing performance of human serum based matrix for culturing hESCs. Hyeyeon Jeong provided assistance with graphical presentation of data.

Funding: NHLBI – NIH grant K08 HL081076 to P.H. and HL52955 to E. Z.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authorship: J.K., E.Z., D.G. and P.H. designed the study. J.K., C.J. and D.G. performed experiments. J.K., D.G., and C.J. collected data. J.K., D.G. and P.H. analyzed data. P.H. provided study material. J.K., D.G. and P.H. wrote manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The authors do not have any relevant conflict of interest.

Competing interests: J.K. and P.H. filed a patent application for “Use of human tissue-specific mesenchymal stem cells and macrophages for generation of tissue-specific cells for therapeutic purposes” PCT/US2010/046512.

References

- 1.Kaufman DS. Toward clinical therapies using hematopoietic cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Blood. 2009;114:3513–3523. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-191304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riviere I, Dunbar CE, Sadelain M. Hematopoietic stem cell engineering at a crossroads. Blood. 2012;119:1107–1116. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-349993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim PG, Daley GQ. Application of induced pluripotent stem cells to hematologic disease. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:980–989. doi: 10.3109/14653240903348319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyba M, Daley GQ. Hematopoiesis from embryonic stem cells: lessons from and for ontogeny. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:994–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodrich AD, Ersek A, Varain NM, et al. In vivo generation of beta-cell-like cells from CD34(+) cells differentiated from human embryonic stem cells. Exp Hematol. 2010;38:516–525. e514. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufman DS, Thomson JA. Human ES cells--haematopoiesis and transplantation strategies. Journal of anatomy. 2002;200:243–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drukker M, Katchman H, Katz G, et al. Human embryonic stem cells and their differentiated derivatives are less susceptible to immune rejection than adult cells. STEM CELLS. 2006;24:221–229. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merianos D, Heaton T, Flake AW. In utero hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: progress toward clinical application. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung W, Blakemore K, Jones RJ, et al. A human-murine chimera model for in utero human hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1999;5:1–7. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.1999.v5.pm10232735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyba M, Perlingeiro RCR, Daley GQ. HoxB4 Confers Definitive Lymphoid-Myeloid Engraftment Potential on Embryonic Stem Cell and Yolk Sac Hematopoietic Progenitors. Cell. 2002;109:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee G, Kim B, Sheih J, Moore M. Forced expression of HoxB4 enhances hematopoietic differentiation by human embryonic stem cells. Mol Cells. 2008;25:487–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Menendez P, Shojaei F, et al. Generation of hematopoietic repopulating cells from human embryonic stem cells independent of ectopic HOXB4 expression. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1603–1614. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian X, Woll PS, Morris JK, Linehan JL, Kaufman DS. Hematopoietic Engraftment of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Cells Is Regulated by Recipient Innate Immunity. STEM CELLS. 2006;24:1370–1380. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledran MH, Krassowska A, Armstrong L, et al. Efficient hematopoietic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells on stromal cells derived from hematopoietic niches. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:85–98. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woods N-B, Parker AS, Moraghebi R, et al. Brief Report: Efficient Generation of Hematopoietic Precursors and Progenitors from Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Lines. STEM CELLS. 2011;29:1158–1164. doi: 10.1002/stem.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Hematti P. Mesenchymal stem cell-educated macrophages: a novel type of alternatively activated macrophages. Experimental hematology. 2009;37:1445–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J, Denu RA, Dollar BA, et al. Macrophages and mesenchymal stromal cells support survival and proliferation of multiple myeloma cells. British journal of haematology. 2012;158:336–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winkler IG, Sims NA, Pettit AR, et al. Bone marrow macrophages maintain hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niches and their depletion mobilizes HSC. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chow A, Lucas D, Hidalgo A, et al. Bone marrow CD169+ macrophages promote the retention of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mesenchymal stem cell niche. J Exp Med. 2011;208:261–271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trivedi P, Hematti P. Derivation and immunological characterization of mesenchymal stromal cells from human embryonic stem cells. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergkvist A, Rusnakova V, Sindelka R, et al. Gene expression profiling--Clusters of possibilities. Methods. 2010;50:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beyene J, Tritchler D, Bull SB, et al. Multivariate analysis of complex gene expression and clinical phenotypes with genetic marker data. Genet Epidemiol. 2007;31(Suppl 1):S103–S109. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagao Y, Abe T, Hasegawa H, et al. Improved efficacy and safety of in utero cell transplantation in sheep using an ultrasound-guided method. Cloning and stem cells. 2009;11:281–285. doi: 10.1089/clo.2008.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narayan AD, Chase JL, Lewis RL, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived hematopoietic cells are capable of engrafting primary as well as secondary fetal sheep recipients. Blood. 2006;107:2180–2183. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleinman HK, McGarvey ML, Liotta LA, Robey PG, Tryggvason K, Martin GR. Isolation and characterization of type IV procollagen, laminin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycan from the EHS sarcoma. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6188–6193. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Battiwalla M, Hematti P. Mesenchymal stem cells in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:503–515. doi: 10.1080/14653240903193806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin T, Li L. The stem cell niches in bone. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1195–1201. doi: 10.1172/JCI28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bianco P, Gehron Robey P. Marrow stromal stem cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2000;105:1663–1668. doi: 10.1172/JCI10413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dexter TM. Stromal cell associated haemopoiesis. Journal of cellular physiology Supplement. 1982;1:87–94. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041130414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells: new directions. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horwitz EM, Maziarz RT, Kebriaei P. MSCs in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:S21–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colmone A, Amorim M, Pontier AL, Wang S, Jablonski E, Sipkins DA. Leukemic cells create bone marrow niches that disrupt the behavior of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. Science. 2008;322:1861–1865. doi: 10.1126/science.1164390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basak GW, Srivastava AS, Malhotra R, Carrier E. Multiple myeloma bone marrow niche. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2009;10:345–346. doi: 10.2174/138920109787847493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vodyanik MA, Bork JA, Thomson JA, Slukvin II. Human embryonic stem cell-derived CD34+ cells: efficient production in the coculture with OP9 stromal cells and analysis of lymphohematopoietic potential. Blood. 2005;105:617–626. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaufman DS, Hanson ET, Lewis RL, Auerbach R, Thomson JA. Hematopoietic colony-forming cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:10716–10721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191362598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vodyanik MA, Thomson JA, Slukvin II. Leukosialin (CD43) defines hematopoietic progenitors in human embryonic stem cell differentiation cultures. Blood. 2006;108:2095–2105. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai S, Emerson SG, Sieff CA, Nathan DG. Isolation of a human stromal cell strain secreting hemopoietic growth factors. J Cell Physiol. 1986;127:137–145. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041270117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winkler IG, Sims NA, Pettit AR, et al. Bone marrow macrophages maintain hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niches and their depletion mobilizes HSCs. Blood. 2010;116:4815–4828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ludin A, Itkin T, Gur-Cohen S, et al. Monocytes-macrophages that express alpha-smooth muscle actin preserve primitive hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ni.2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rofani C, Luchetti L, Testa G, et al. IL-16 can synergize with early acting cytokines to expand ex vivo CD34+ isolated from cord blood. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:671–682. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zandstra PW, Conneally E, Petzer AL, Piret JM, Eaves CJ. Cytokine manipulation of primitive human hematopoietic cell self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4698–4703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keil F, Elahi F, Greinix HT, et al. Ex vivo expansion of long-term culture initiating marrow cells by IL-10, SCF, and IL-3. Transfusion. 2002;42:581–587. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner T, Fritsch G, Thalhammer R, et al. IL-10 increases the number of CFU-GM generated by ex vivo expansion of unmanipulated human MNCs and selected CD34+ cells. Transfusion. 2001;41:659–666. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41050659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zambidis ET, Park TS, Yu W, et al. Expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (CD143) identifies and regulates primitive hemangioblasts derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Blood. 2008;112:3601–3614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sinka L, Biasch K, Khazaal I, Peault B, Tavian M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (CD143) specifies emerging lympho-hematopoietic progenitors in the human embryo. Blood. 2012 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-314781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wognum AW, Eaves AC, Thomas TE. Identification and isolation of hematopoietic stem cells. Arch Med Res. 2003;34:461–475. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zambidis ET, Sinka L, Tavian M, et al. Emergence of human angiohematopoietic cells in normal development and from cultured embryonic stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1106:223–232. doi: 10.1196/annals.1392.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katoh O, Tauchi H, Kawaishi K, Kimura A, Satow Y. Expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor gene, KDR, in hematopoietic cells and inhibitory effect of VEGF on apoptotic cell death caused by ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5687–5692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ziegler BL, Valtieri M, Porada GA, et al. KDR receptor: a key marker defining hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1999;285:1553–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin AH, Miraglia S, Zanjani ED, et al. AC133, a novel marker for human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 1997;90:5002–5012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zanjani ED, Pallavicini MG, Ascensao JL, et al. Engraftment and long-term expression of human fetal hemopoietic stem cells in sheep following transplantation in utero. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1178–1188. doi: 10.1172/JCI115701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abe T, Masuda S, Ban H, et al. Ex vivo expansion of human HSCs with Sendai virus vector expressing HoxB4 assessed by sheep in utero transplantation. Experimental hematology. 2011;39:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Almeida-Porada G, Porada C, Gupta N, Torabi A, Thain D, Zanjani ED. The human-sheep chimeras as a model for human stem cell mobilization and evaluation of hematopoietic grafts' potential. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:1594–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zanjani ED, Almeida-Porada G, Flake AW. Retention and multilineage expression of human hematopoietic stem cells in human-sheep chimeras. Stem cells. 1995;13:101–111. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530130202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kiel MJ, Morrison SJ. Uncertainty in the niches that maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:290–301. doi: 10.1038/nri2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.