Abstract

Video recording has become increasingly popular in nursing research, adding rich nonverbal, contextual, and behavioral information. However, benefits of video over audio data have not been well established. We compared communication ratings of audio versus video data using the Emotional Tone Rating Scale. Twenty raters watched video clips of nursing care and rated staff communication on 12 descriptors that reflect dimensions of person-centered and controlling communication. Another group rated audio-only versions of the same clips. Interrater consistency was high within each group with ICC (2,1) for audio = .91, and video = .94. Interrater consistency for both groups combined was also high with ICC (2,1) for audio and video = .95. Communication ratings using audio and video data were highly correlated. The value of video being superior to audio recorded data should be evaluated in designing studies evaluating nursing care.

Keywords: audio data, video data, communication, research methods, gerontology

Video recordings are gaining popularity as a reliable and valid research method in nursing and health care disciplines because of their ability to capture and preserve rich contextual observational data about interactions between people in health care settings (Riley & Manias, 2004). It is believed that video data is contextually superior to audio recording, because it provides observational data about nonverbal communication and specific behavior (Haidet, Tate, Divirgilio-Thomas, Kolanowski, & Happ, 2009; Pierce, 2005). For example, audio data may be inadequate for a comprehensive evaluation of an infant's response to pain because although crying may be heard, facial expressions and body language cannot be seen. This study was designed to evaluate whether ratings of nursing staff communication differed within qualitative dimensions of person-centered and controlling communication, when audio compared to video recorded data was used.

Description of the Problem

Both audio and video recordings are valuable tools for investigating phenomenon that are complex and about which little is known, such as communication (Bottorff, 1994). However, recorded data is two dimensional, and thus less accurate than direct observation (Halimmaa, 2001). Despite this limitation recordings allow repeated reviewing of data to observe multiple behaviors and relationships among phenomena of interest. Repeated playing permits the investigator to focus on different factors each time so that multiple participants in interactions and a variety of factors in the environment can be analyzed and relationships between factors can be established. Sequential analyses can be used to link conditions and events in time and to assess antecedents and consequences of phenomena of interest (Roth, Stevens, Burgio, & Burgio, 2002; Williams, Herman, Gajewski, &Wilson 2009).

Recordings can be used alone or in combination with surveys and interviews to augment self-reported information that may be less accurate than observed behavior (Halimaa, 2001; Pierce, 2005). Recent technological advances support video recording of observational data. However, evidence supporting the added value of video over audio recorded data is mixed and a careful evaluation of benefits of video recorded data in relation to costs, data management requirements, and the research question is warranted (Dent, Brown, Dowsett, Tattersall, & Butow, 2005; Howe, 1997; Leong, Koczan, De Lusignan, & Sheeler, 2006a; Weingarten, Yaphe, Blumenthal, Oren, & Margalit, 2001).

Because of the complexity of interpersonal relationships that are an integral part of nursing and health care, recording has become a mainstay for research on health care provider and patient communication across settings (Beck, Daughtridge, & Sloane, 2002; Levy-Storms, 2008) and clinical populations (Haidet et al., 2009). Our research has used both audio only and video recordings. We used audio only to transcribe and code staff-resident conversations in nursing homes to quantify elderspeak (infantilizing) communication (Williams, Kemper, & Hummert, 2003). In other research video data was instrumental in linking nursing communication to behavioral responses in nursing home residents with dementia (Williams, Herman, Gajewski, & Wilson, 2009).

Audio recording is generally less intrusive than video recording because an investigator does not have to operate the camera (although cameras may be mounted for remote recording, this practice is rarely used due to privacy issues). Because an operator is needed and readily observed by research subjects, video recording may alter naturally occurring communication more than audio recording. Video recording is in itself more complex requiring attention to both sound and visual capture of data. Audio equipment is generally less expensive, and training of research staff in its use is less intense than video recording. Video file sizes can be excessive with added expense for storage as well as for time and materials necessary for recording and archiving data.

Ethical issues surrounding collection of both audio and video recorded research data center on protecting the rights and privacy of research subjects (Broyles, Tate, & Happ, 2008). Strong safeguards are necessary to avoid unauthorized release of sound and video data collected during sensitive care sessions that could result in embarrassment or punitive actions. If unauthorized disclosure of data occurs, participant voices are more difficult to identify than visually identifiable video recordings. This data may contain health information and require protection under the Health Information Portability and Privacy Act (HIPPA). Video data may require encryption as an added data security measure.

In our nursing home research, some families have hesitated to consent to having their loved one captured on film displaying behaviors common in persons with advanced dementia. Vulnerable persons or their surrogate decision makers may be less likely to consent to video recording that is more readily identifiable than audio recordings (Howe, 1997). Staff have also been more reluctant to participate in video compared to audio recordings without assurance that supervisors will not have access to recordings or that facial features will be blurred. In general, staff, patients, and families are more willing to participate in audio recordings.

Purpose

Our research exploring communication in nursing home and dementia care has utilized both audio and video data collection. We hypothesized that video recordings may provide added nonverbal data essential to effective communication measurement. This hypothesis was based on theories of patronizing communication (elderspeak), recognizing that “when verbal and nonverbal meanings conflict, the nonverbal message carries greater significance and colors interpretation of the verbal features (p. 153, Ryan, Hummert, & Boich, 1995).” To test this hypothesis, we compared ratings of nursing staff communication from video and audio-only versions of recorded communication using the Emotional Tone Rating Scale (ETRS) (Williams, Boyle, Herman, Coleman, & Hummert, 2012). The ETRS was developed to measure affective qualities in nursing home communication and prior analyses of recorded data yielded two contrasting factors “person-centered” and “controlling” communication (Williams et al., 2012). In this use, “person-centered” refers to communication that acknowledges the recipient as an individual and worthy communication partner. Our hypothesis was that audio and video data could provide disparate results due to the added information provided in the video recordings.

Methods

The ETRS was used to evaluate staff communication in 20 recordings of bathing care interactions, collected as part of an observational study (Williams et al., 2009). Bathing care was selected because it provides the opportunity for one-on-one communication between staff and residents. The 1-minute recordings included a staff person and a resident during bathing. Twenty raters watched each video clip twice and then rated staff communication using the ETRS (12 descriptors that reflect care, respect, and control). The raters were not given definitions for the rating scale descriptors nor instructions beyond asking them to rate the staff person's communication. While training may have increased reliability between raters, use of naïve raters may mimic that of a resident in a naturally occurring communication encounter.

A second group of 20 raters analyzed the same clips using the audio only versions of the same recordings. Correlations between ratings from the two groups were compared and t-test comparisons and factor analysis were performed to detect differences in scale items and factors when using audio versus video data.

The Emotional Tone Rating Scale

In a recent observational study evaluating how nursing home residents with dementia respond to differing styles of nursing staff communication, we used video recordings that linked staff elderspeak communication and resident resistiveness to care (Herman & Williams, 2009; Williams & Herman, 2011; Williams et al., 2009). The ETRS, one communication measure used in the study, was initially developed based on theoretical imbalances in dimensions of care, respect, and control in nursing home communication (Hummert & Ryan, 1996; Ryan, Meredith, & Shantz, 1994). For example, staff may issue commands such as “We need to eat lunch now.” As care providers they have elevated power or control over residents, who also receive less respectful communication. Inappropriately intimate terms of endearment such as “honey” and “sweetie” may be used to reduce these messages of control and instead convey caring, frequently resulting in infantilizing elderspeak communication (Williams, 2011).

The original ETRS measure was designed to assess underlying affective messages using descriptive adjectives that represent three theoretical dimensions of emotional tone: care (nurturance, caring, warmth, and support), respect (polite, affirming, respectful, and patronizing [reverse coded]), and control (dominating, controlling, bossy, and directive) (Hummert, Shaner, Garstka, & Henry, 1998; Williams et al., 2003). Naïve raters rated communication using a five-point Likert scale indicating the degree to which the staff person's communication exhibited each of the 12 descriptors (1=not at all to 5=very). Internal consistency among raters using the ETRS was established in prior research (Cronbach's alphas for caring=.91, respect=.85, and control=.90) with correlations among the four items in each dimension ranging from .46 to .78 (Williams, 2001). The scale also demonstrated relatively high variances with means close to the center of the range within each dimension: care M =13.06, SD = 4.11; respect M = 12.53, SD = 4.13; and control M = 12.27, SD = 4.65. Subsequent exploratory factor analysis (EFA) found that the ETRS best fit an underlying two-factor structure, interpreted as person-centered versus control-centered communication (Williams, et al., 2012). EFA solutions and additional psychometric properties of the ETRS have been reported elsewhere (Williams, et al., 2012).

Parent Study

Twenty video recorded interactions (recordings) between nursing staff and residents with dementia, collected during bathing with a hand-held recorder using strategies to minimize reactivity and the Hawthorne effect (Caris-Verhallen, Kerkstra, van der Heijden, & Bensing, 1998) were reanalyzed in this study. Demographic information about the nursing home residents and staff included in the video recordings collected in the original study are reported elsewhere (Williams et al., 2009). The recordings were collected as part of an observational study conducted in 3 nursing homes in the Midwest. Inclusion criteria for residents (N=20) was a diagnosis of dementia, requiring assistance with ADLs, history of resistiveness to ADL care, and ability to respond to verbal communication. Nursing staff (N = 52) were included who had a permanent position on the unit of the resident's residence and who spoke English. Recordings were screened to include only clips that provided clear visualization of the staff and resident and audio of adequate quality for transcription. The analysis was limited to 20 recordings due to the extensive time required for 20 individuals to view, review, and rate each recording.

Procedures

To evaluate qualitative or affective messages specific to the nursing staff communication, naïve raters (N=20) who were blinded to the study aims were recruited to rate the staff communication in each video clip using the ETRS. Each rater completed Human Subjects Protections training as required for Institutional Review Board approval. To reduce burden, only the first minute of each recording was rated. The initial minute of care interactions has been established as representative in prior research (Caris-Verhallen et al., 1998). The conversations were randomly ordered and presented twice via computer using MediaLab computer software (Empirisoft, 1997 version). A second group of volunteers independently rated versions of the same recordings that only included audio. Interrater consistency was high within each group with ICC (2,1) for audio = .91, and video = .94. Interrater consistency for both groups combined was also high with ICC (2,1) for audio and video = .95.

Analysis

The planned analyses included two-level exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and a multilevel regression analysis with crossed-random intercepts. Two-level EFA (recordings within subject) of rating items was conducted in MPlus (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2011). For this EFA, the within-person solution was of interest. Contrast of EFA solutions from the audio-only and audio video rating data was used to evaluate and compare factor structures and loadings for each recording method. The multilevel regression analysis was conducted with Stata's xtmixed command (StataCorp, 2011), and used crossed-random intercepts to handle dependencies due to repeated observation of items by subject and repeated observation of items by recording.

Findings

ETRS raters were recruited from university health professional graduate and undergraduate students and faculty. Participants in both groups were 20 to 59 years of age and responded to a posted advertisement. Groups in the convenience samples were equivalent with ninety percent female and 80% Caucasian.

Within person correlations of ratings/items between audio and video conditions (tabulated in Table 1) were estimated by the two-level EFA procedure. The majority of the within-person item correlations agreed across recording modes within + - 0.10. See Table 1 for full correlation matrix.

Table 1.

Correlation Matrices and EFA Solutions for Audio and Video ETRS Ratings.

| Video Soluton | SU | NU | CA | WA | PO | RE | AF | PA | DO | CO | BO | DI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audio Solution | f1 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.28 | -0.20 | -0.21 | -0.34 | 0.26 | |

| f1 | f2 | -0.11 | -0.10 | 0.31 | -0.46 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.82 | |||||

| Supportive (SU) | 0.95 | - | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.52 | 0.59 | -0.66 | -0.68 | -0.76 | -0.32 | |

| Nurturing (NU) | 0.99 | 0.08 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.52 | 0.57 | -0.71 | -0.72 | -0.79 | -0.34 | |

| Caring (CA) | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.51 | 0.55 | -0.71 | -0.73 | -0.77 | -0.35 | ||

| Warm (WA) | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.47 | 0.47 | -0.66 | -0.67 | -0.73 | -0.31 | ||

| Polite (PO) | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.48 | 0.55 | -0.71 | -0.73 | -0.79 | -0.35 | ||

| Respectful (RE) | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.55 | 0.60 | -0.72 | -0.75 | -0.80 | -0.31 | ||

| Affirming (AF) | 0.91 | 0.16 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.32 | -0.31 | -0.33 | -0.41 | 0.08 | |

| Patronizing (PA) | -0.51 | 0.30 | -0.64 | -0.57 | -0.60 | -0.60 | -0.63 | -0.64 | -0.52 | -0.61 | -0.67 | -0.68 | -0.36 | |

| Dominating (DO) | -0.63 | 0.47 | -0.81 | -0.79 | -0.82 | -0.79 | -0.82 | -0.83 | -0.69 | 0.70 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.53 | |

| Controlling (CO) | -0.62 | 0.49 | -0.81 | -0.79 | -0.80 | -0.79 | -0.81 | -0.82 | -0.68 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.54 | |

| Bossy (BO) | -0.64 | 0.43 | -0.80 | -0.80 | -0.81 | -0.79 | -0.83 | -0.82 | -0.66 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.56 | |

| Directive (DI) | 0.65 | -0.14 | -0.12 | -0.15 | -0.16 | -0.15 | -0.15 | -0.02 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.36 | ||

The correlations underlying the Audio EFA solution are in the upper triangle, and the correlations underlying the Video EFA solution are in the lower triangle.

Item correlations for items within each factor are in bold, while correlations of items with items on the other factor are in plain text.

To facilitate comparison of item correlations across recording mode, within-factor item correlations agreeing +- 0.10 are underlined. This is most items, with the exception of patronizing.

The audio EFA solution is presented in the top margin, and the Video EFA solution is presented in the left margin. Small loadings <.08, or any loadings not significant at the p=.05 level , are not tabulated.

To test the effect of recording mode on ETRS item ratings, we fit a crossed random intercept model (i.e., repeated observation of items by subject, and repeated observation of items by clip), and requested independent residual variances for each item. The clips selected for this study are a random sample of clips, and the importance of modeling variation due to stimuli in addition to variation due to subjects has been increasingly recognized (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008; Janssen, 2012; Judd, Westfall, & Kenny, 2012; Locker, Hoffman, & Bovaird, 2007). Table 2 shows the estimated marginal means overall for audio-only and audio-video, as well as separately for each ETRS item. While a few items (i.e., respect, patronizing support, polite) showed significant differences at the 95% confidence level, only patronizing is of concern. These p-values are not adjusted for multiple comparisons, and the standardized effects for respect, support, and polite are small. All items except patronizing become nonsignificant when adjusting the p level for significance to 0.01 to control for multiple comparisons.

Table 2.

Comparisons of Emotional Tone Item Ratings Audio versus Video Data

| Item | Audio | Video | Difference | SEDiff | est/SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-Centered | ||||||

| Nurturing | 2.74 | 2.88 | 0.14 | 0.123 | 1.14 | 0.254 |

| Affirming | 2.75 | 2.91 | 0.15 | 0.122 | 1.25 | 0.213 |

| Respectful | 2.90 | 3.15 | 0.24 | 0.121 | 2.00 | 0.045 |

| Supportive | 2.81 | 3.08 | 0.27 | 0.121 | 2.23 | 0.026 |

| Polite | 2.97 | 3.26 | 0.28 | 0.122 | 2.32 | 0.020 |

| Caring | 2.91 | 3.14 | 0.23 | 0.120 | 1.92 | 0.055 |

| Warm | 2.79 | 2.93 | 0.15 | 0.123 | 1.20 | 0.229 |

| Control-Centered | ||||||

| Directive | 3.61 | 3.62 | 0.01 | 0.136 | 0.07 | 0.941 |

| Patronizing | 3.47 | 2.36 | -1.11 | 0.145 | -7.63 | 0.000* |

| Bossy | 2.90 | 2.74 | -0.17 | 0.166 | -0.99 | 0.321 |

| Dominating | 2.87 | 2.72 | -0.15 | 0.164 | -0.91 | 0.361 |

| Controlling | 2.96 | 2.75 | -0.21 | 0.165 | -1.26 | 0.207 |

Significant at the p = .001 level (adjusted for multiple comparisons)

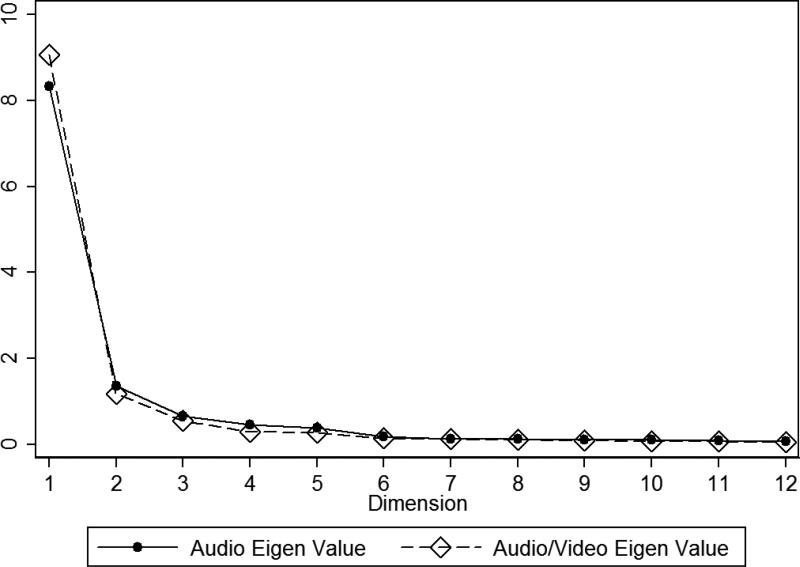

Additional examination of potential recording mode effects on the ETRS factor structure was undertaken by comparing EFA solutions for audio-only and audio-video conditions. See factor loadings in Table 1. Previous findings from audio-only data that suggested that the ETRS was best fit by a 2 factor (controlling and person-centered) model (Williams et al., 2012) with care and respect collapsed into one factor (person-centered). The two-level EFA of data from the present study confirmed that ratings of both audio and video recordings supported the published two-factor solution. The scree plot (see Figure 1) confirms our earlier psychometric analysis finding that 2, not 3 factors, are present for both audio only and video ratings. Using Cattel's method for visual inspection, it is apparent that 2 factors fall at or above the elbow (Cramer, 2003).

Figure 1.

Scree plot of Audio and Audio-Video Emotional Tone Rating Scale Data.

EFA also revealed that audio-only and video data yielded highly comparable solutions with similar loadings on two negatively correlated person-centered and controlling dimensions (-0.6209 for audio-only and -0.6596 for video data ratings respectively). These findings replicate the two-factor ETRS model suggested in our earlier research (Williams et al., 2012).

EFA solutions did show small differences in factor loading patterns. Further psychometric analysis is underway to determine whether removing patronizing and other items that were unstable (or not discriminating) could result in an 8-item scale with the same predictive ability and better psychometric properties.

Discussion

The high agreement of the ETRS ratings for audio and video data was unexpected. However, many nonverbal communication features critical to affective messages, such as voice pitch, tone, and speech rate, were actually included in the audio-only recordings. Visual communication behaviors such as gestures, facial expressions, proxemics, and body movements, observable only with video recordings, did not alter scale findings significantly. This versatility of the ETRS as an observational measure for both audio and video recorded data may be due to its focus on theory-defined imbalances in care, respect, and control that determine person-centered versus controlling messages conveyed in nursing home communication (Curyto, Van Haitsma, & Vriesman, 2008). To further evaluate our hypothesis that evaluation of video data would provide disparate results from audio only data in evaluating qualitative messages because of the stronger message in nonverbal communication, future research should focus on interactions where verbal and nonverbal messages conflict.

The analytical results indicate that the ETRS encompasses two nearly identical factors whether using audio-only or audio-video media. This supports our prior findings of a two-factor solution (Williams et al., 2012) that fits within the conceptual definitions of person-centered care (Edvardson & Innes, 2010; ). The 2-factor solution also provides a simpler framework for understanding aspects of person-centered communication. Future work will explore potential reductions in items to better reflect the controlling and person-centered factors, this may increase the efficiency and reduce the burden of ETRS use.

For example eliminating the item patronizing which has been identified as confusing and poorly understood by coders may strengthen the scale psychometrically. Because patronizing is not in common use, raters may have been unsure of its meaning and whether a positive or negative descriptor. A patron may be understood as an autonomous and generous customer in contrast to the adjective patronizing that implies treating the person with artificial kindness. Items like directive can be ambiguous because it is sometimes supportive (as in giving directions) and thus person-centered compared to controlling (being told what to do) and must be interpreted cautiously. While the loadings for directive were similar in audio-only and audio-video solutions, the relatively high loadings on both factors indicate that directive is not a very discriminating (i.e., useful) item. However it is possible that after removing the patronizing item and dropping highly redundant items, that the directive item would be more discriminating in an ETRS short form version.

This study used a relatively small sample and one communication measure and cannot be generalized to other research questions, populations, or measures. In addition, although groups were statistically similar on key demographic factors, the audio and video groups included different raters. Considering the increased costs and difficulty of video recording (including recruiting and consent, ethical issues, and costs for equipment and training), it is important to evaluate the need for video recording when audio data may suffice. It is important to evaluate the cost-benefit-effectiveness analysis in planning research.

The results of this study contrast with other research findings recently reported in the literature that video recording is essential for capturing non-verbal cues in communication to evaluate care. For example, research comparing audio and video recordings of doctor-patient interactions used for training physicians, found video data was necessary to measure provider-patient communication, and that multiple cameras were needed to capture the details of medical encounters (Leong, Koczan, De Lusignan, & Sheeler, 2006b). This contrast may be due to the ETRS addressing only global affective qualities of interactions in comparison to other instruments that additionally identify the presence of specific behaviors to measure person-centered communication (Edvardson & Innes, 2010). Our research supports previous studies that found audio-only recordings are equivalent to video for analysis of affective qualities of caregiver-care recipient interactions (Dent et al., 2005; Weingarten et al., 2001). The research question and target phenomena are important to consider in relation to relative costs in selecting a mode of recording.

Our study suggests the ETRS is a reliable scale to measure qualitative aspects of nursing home communication with either audio only or video recorded data. Notably, the ability to measure global affective qualities of interactions without requiring transcription suggests that the ETRS has potential for teaching care providers to monitor their own communication with care recipients during busy clinical practice. Considering the additional costs and requirements associated with video recording in clinical settings, audio recordings may provide a more cost efficient method for many research studies in nursing and health. The choice of recording method should be carefully considered in planning research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NINR grant NR009231-02, Elderspeak: Impact on Dementia Care.

Contributor Information

Kristine Williams, School of Nursing, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas, and Gerontology Center, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas.

Ruth Herman, School of Nursing, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas.

Daniel Bontempo, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS..

References

- Baayen RH, Davidson DJ, Bates DM. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;59(4):390–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005. [Google Scholar]

- Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2002;15(1):25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff J. Using videotaped recordings in qualitative research. In: Morse J, editor. Critical issues in qualitative research methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. pp. 244–261. [Google Scholar]

- Broyles LM, Tate JA, Happ MB. Videorecording in clinical research: Mapping the ethical terrain. Nursing Research. 2008;57(1):59–63. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000280658.81136.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caris-Verhallen W, Kerkstra A, van der Heijden P, Bensing J. Nurse-elderly patient communication in home care and institutional care: An explorative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1998;35:95–108. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(97)00039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curyto KI, Van Haitsma K, Vriesman DK. Direct observation of behavior: A review of current measures for use with older adults with dementia. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2008;1(1):52–76. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20080101-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent E, Brown R, Dowsett S, Tattersall M, Butow P. The Cancode interaction analysis system in the oncological setting: reliability and validity of video and audio tape coding. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.11.010. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidet KK, Tate J, Divirgilio-Thomas D, Kolanowski A, Happ MB. Methods to improve reliability of video-recorded behavioral data. Research in Nursing & Health. 2009;32:465–474. doi: 10.1002/nur.20334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halimaa S. Video recording as a method of data collection in nursing research. Vård i Norden. 2001;21(2):21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Herman R, Williams K. Elderspeak's influence on resistiveness to care: Focus on specific behavioral events in dementia care. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2009;24:417–423. doi: 10.1177/1533317509341949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe A. Refusal of videorecording: what factors may influence patient consent? Fam Pract. 1997;14(3):233–237. doi: 10.1093/fampra/14.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummert ML, Ryan EB. Toward understanding variations in patronizing talk addressed to older adults: Psycholinguistic features of care and control. International Journal of Psycholinguistics. 1996;12(2):149–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hummert ML, Shaner J, Garstka T, Henry C. Communication with older adults: The influence of age stereotypes, context, and communicator age. Human Communication Research. 1998;25(1):124–151. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen DP. Twice random, once mixed: Applying mixed models to simultaneously analyze random effects of language and participants. Behavior Research Methods. 2012;44(1):232–247. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0145-1. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd CM, Westfall J, Kenny DA. Treating Stimuli as a Random Factor in Social Psychology: A New and Comprehensive Solution to a Pervasive but Largely Ignored Problem. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2012;103(1):54–69. doi: 10.1037/a0028347. doi: 10.1037/a0028347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong A, Koczan P, De Lusignan S, Sheeler I. A framework for comparing video methods used to assess the clinical consultation: a qualitative study. Med Inform Internet Med. 2006a;31(4):255–265. doi: 10.1080/14639230600991668. doi: 10.1080/14639230600991668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong A, Koczan P, De Lusignan S, Sheeler I. A framework for comparing video methods used to assess the clinical consultation: A qualitative study. Informatics for Health and Social Care. 2006b;31(4):255–265. doi: 10.1080/14639230600991668. doi: doi:10.1080/14639230600991668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Storms L. Therapeutic communication training in long-term care institutions: Recommendations for future research. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;73:8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locker L, Hoffman L, Bovaird JA. On the use of multilevel modeling as an alternative to items analysis in psycholinguistic research. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(4):723–730. doi: 10.3758/bf03192962. doi: 10.3758/bf03192962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Muthen L. MPlus Computer Software (Version v6.11) Los Angeles: 1998-2011. Retrieved from www.statmodel.com. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce D. The usefulness of video methods for occupational therapy and occupational science research. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2005;59(1):9–19. doi: 10.5014/ajot.59.1.9. doi: 10.5014/ajot.59.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley RG, Manias E. The uses of photography in clinical nursing practice and research: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;48(4):397–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03208.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan E, Meredith S, Shantz G. Evaluative perceptions of patronizing speech addressed to institutionalized elders in contrasting conversational contexts. Canadian Journal on Aging. 1994;13(2):236–248. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten MA, Yaphe J, Blumenthal D, Oren M, Margalit A. A comparison of videotape and audiotape assessment of patient-centredness in family physicians’ consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(2):107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Herman R. Linking resident behavior to dementia care communication: Effects of emotional tone. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42(1):42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Herman R, Gajewski B, Wilson K. Elderspeak communication: Impact on dementia care. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2009;24:11–20. doi: 10.1177/1533317508318472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Kemper S, Hummert ML. Improving nursing home communication: An intervention to reduce elderspeak. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):242–247. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KN. Improving nursing home communication Dissertation Abstracts International (Vol. 62 (06A)) University of Kansas; Lawrence: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KN. Elderspeak in institutional care of older adults. In: Bachhaus P, editor. Communication in Elderly Care: Cross-cultural Perspectives. Continuum; London and New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]