Abstract

Transcription activator-like (TAL) effectors are transcription factors injected into plant cells by pathogenic bacteria in the genus Xanthomonas. They function as virulence factors by activating host genes important for disease, or as avirulence factors by turning on genes that provide resistance. DNA binding specificity is encoded by polymorphic repeats in each protein that correspond one-to-one with different nucleotides. This code has facilitated target identification and opened new avenues for engineering disease resistance. It has also enabled TAL effector customization for targeted gene control, genome editing, and other applications. This article reviews the structural basis for TAL effector-DNA specificity, the impact of the TAL effector-DNA code on plant pathology and engineered resistance, and recent accomplishments and future challenges in TAL effector-based DNA targeting.

Keywords: DNA-targeting, plant disease, susceptibility genes, resistance genes, crystal structure, gene therapy, TAL effector nucleases

Overview of TAL effectors

TAL (transcription activator-like) effectors are transcriptional activators injected into plant cells by plant pathogenic members of the bacterial genus Xanthomonas. In the plant nucleus, TAL effectors act as virulence factors by turning on genes necessary for disease susceptibility (S genes), or in a few cases, as avirulence factors by activating a gene that confers resistance (an R gene) [1, 2]. TAL effectors recognize their targets via a central protein domain composed of a variable number of tandem, 33-34 amino acid repeats. The repeats are nearly identical, with variation occurring primarily at amino acids 12 and 13. These two positions are known as the repeat variable diresidue (RVD). The sequence of RVDs has been shown both computationally and experimentally, and more recently structurally, to “encode” the TAL effector binding site on the DNA, with each RVD specifying a single binding site nucleotide through direct interaction [3-6].

This modularity is so far unique among DNA binding proteins. Of the most prevalent protein folds that bind DNA, including zinc fingers, helix-turn-helix motifs, and leucine zippers, only zinc fingers approach modularity. Individual fingers recognize nucleotide triplets, and finger arrays can be assembled to target long sequences that are multiples of three. Yet only a small fraction of all possible nucleotide triplets are accounted for by fingers observed in nature, and engineering fingers with new specificities is to a large extent empirical and therefore labor and time intensive. What is more, specificity and functionality of individual fingers is affected by neighboring fingers. The truly modular nature of TAL effector RVD interactions with individual nucleotides makes these proteins remarkably adaptable virulence factors and remarkably useful engineered proteins for DNA targeting. The TAL effector-DNA “code” is improving our understanding of the role of TAL effectors in plant diseases and is informing efforts to develop more effective means to control those diseases. The customizability of TAL effectors has led to widely enabling TAL effector-based tools for systems biology and genome engineering, advancing fundamental research, crop and livestock improvement, and medicine [1, 7].

From the effects these proteins have on plant cells to the effects they are having on the life sciences and biotechnology, TAL effectors are a fascinating and useful invention of nature. TAL effector research is moving fast. Since the discovery of the RVD-nucleotide code in 2009, the number of papers related to TAL effector function and application has risen sharply and steadily, from fewer than ten in 2009 to over 110 in 2012 [8]. In this review, we discuss highlights concerning the structural basis for TAL effector-DNA binding and specificity, the roles of TAL effectors in plant pathology and engineered plant disease resistance, TAL effector-based applications, and future challenges for TAL effector research.

TAL effector structure and function

The four most common RVDs, HD, NG, NN, and NI, respectively specify C, T, G or A, and A. Other RVDs of interest for DNA targeting include NS and N* (the asterisk represents a missing amino acid at position 13, resulting in a 33 amino acid repeat), which have lax specificity, and the less common NH, which has stringent specificity for G [9]. Another rare RVD, NK, also has stringent specificity for G but demonstrates poor relative affinity [10]). Recent crystallization studies of two different TAL effectors provide a clear view of the structural basis and context for all of these interactions but those of NH and NK, which were not present in either of the proteins. One of the studies illustrates the free and DNA-bound forms of the repeat region of an artificially engineered TAL effector termed 'dHAX3', that contains 11 canonical TAL repeats and three of the most common RVDs (HD, NG and NS) [6]. The other presents the DNA-bound structure of the repeat region of the naturally occurring TAL effector PthXo1 from X. oryzae [5] (Figure 1). That structure contains over 20 repeats bound to two full turns of DNA and six RVDs (HD, NG, NN, NI, N*, and the rare HG), as well as a portion of a positively charged N-terminal region that interacts nonspecifically with the 5’ DNA region preceding the target site.

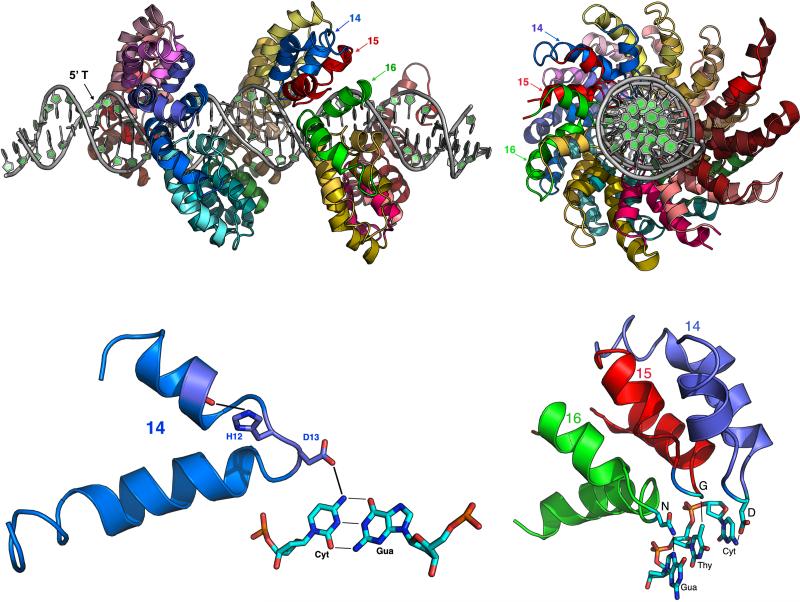

Figure 1. Structure of the TAL effector-DNA association and the basis of specificity.

At top, the structure of PthXo1 bound to its DNA target site [5] is shown (left) from the side of the DNA duplex and (right) looking down the axis of the DNA. The effector contains 22.5 repeat modules each colored separately. In the side view, the N-terminal end of the protein is leftmost. It contains two cryptic repeats that engage the DNA backbone via a series of basic residues, and that also capture the strongly conserved thymine (5’ T) at position ‘zero’ of the binding site. The labeled repeats (14, 15, and 16) are shown in detail at bottom. Bottom left illustrates the contacts made by the ‘HD’ RVD (residues 12 and 13) in repeat number 14. The histidine at position 12 in the repeat forms a hydrogen bond to the backbone carbonyl oxygen of residue 8 in the first alpha-helix, while the aspartate at position 13 forms a hydrogen bond to the extracyclic amino nitrogen of the cytosine base. Bottom right shows repeats 14, 15, and 16 interacting with the DNA, illustrating that consecutive RVDs (HD, NG and NN, respectively in these repeats) contact consecutive bases (cytosine, thymine, and guanine in this case) on the same DNA strand.

Each TAL repeat (in both proteins) forms a two-helix bundle. The RVD resides in a well-ordered interhelical loop. The individual repeats self-associate to wrap around the entire length of the unbent DNA target site. Unbound dHAX3 displays a slightly unwound, but still helical structure [6]. Thus, a significantly more extended effector conformation appears to be required for DNA target acquisition. This hypothesis agrees with small angle X-ray scattering data obtained using another (and full length) TAL effector, PthA [11]).

The first residue in each RVD (at position 12) orients away from the DNA to interact with the protein backbone carbonyl at position 8, in the first helix of the repeat, and stabilize the interhelical loop. The second residue (position 13) projects deep into the major groove of the DNA and makes sequence-specific contacts with a single nucleotide base; all such contacts are made to a single DNA strand. The majority of observed contacts between the RVDs and DNA bases correspond to (i) directional hydrogen-bonds (observed for ‘HD’ RVDs in contact with cytosine, or for ‘NN’ RVDs in contact with purines), (ii) highly complementary steric packing in the absence of hydrogen bonds (such as between NG or HG RVDs and thymine), or (iii) interactions that appear to achieve reduced (but not completely negligible) specificity through steric exclusion of alternate bases (in particular, the ‘NI’ RVD). The ‘N*’ RVD, in which the RVD loop is truncated by one residue, appears to accommodate any base with little or no contribution to overall affinity. These observations agree with a recent study that examined artificial TAL effectors with blocks of homopolymeric repeats to determine the specificity and contribution to activity, as a proxy for binding affinity, of the most common RVDs and several rare RVDs. This study demonstrated that ‘HD’ and ‘NN’ (or ‘HN') repeats provide a significant contribution to overall TAL effector activity (and therefore, presumably binding affinity), whereas strings of ‘NI’ or ‘N*’ repeats result in considerably lower activity and reduced specificity [9].

The pattern of contacts and specificity described above can be extended to the recognition of modified bases: the presence of an NG or HG repeat (which are specific for thymine in an unmodified target) can accommodate similar interactions with a 5-methyl-cytosine, thus making it possible to identify or design potential TAL effectors that can discriminate between target sites that contain methylated CpG sequences and those that are unmodified [12]. A more recent study indicates that TAL effectors can also recognize the deoxynucleotide-containing strand of RNA-DNA hybrids [13].

The structure of PthXo1 reveals that the highly basic region immediately preceding canonical TAL repeats associates closely with DNA preceding RVD encoded bases [5]. Relatively poor performance of N-terminally truncated artificial TAL constructs missing some or all of this region suggests that the region is critical for high affinity DNA binding [14, 15]. Despite sequence dissimilarity to canonical repeats, amino acids in this region in the PthXo1 structure form two repeat-like helical bundles (“cryptic repeats”), designated, from the N-terminal end, as repeat -1 and repeat 0. In repeat -1, a tryptophan in the interhelical loop engages a thymine base found just prior to RVD encoded bases in nearly all naturally occurring TAL effector targets. This tryptophan is strictly conserved among all observed TAL effectors as well. A recent crystal structure of dHAX3 with most of the N terminal portion included shows that two additional cryptic repeats before repeat -1 also engage DNA, suggesting that this entire region provides the majority of binding energy required for high affinity target binding [16].

Finally, comparison of the structures and individual repeats of dHAX3 and PthXo1 indicates that these proteins display minimal structural differences from one another (r.m.s.d. ~0.8 angstroms across all repeats) despite comprising distinct strings of RVDs that target unrelated DNA target sites. The striking structural conformity across repeats in these two proteins confirms the remarkable modular nature of DNA recognition by TAL effectors that enable the prediction of targets in plant disease, the manipulation of targets for disease resistance, and the customization of TAL effectors for DNA targeting applications.

The natural role of TAL effectors

Different Xanthomonas species collectively infect a wide range of economically important crops and ornamentals. Sequenced Xanthomonas genomes typically encode zero to six TAL effectors, with some encoding upwards of thirty [17]. These have from 1.5-33.5 repeats in their DNA recognition domains, with an average of 17.5 repeats. [2]. The final repeat is the “half repeat”, but, truncated at 20 amino acids and containing an RVD, it is still functional. Despite natural variation in numbers of repeats in naturally occurring TAL effectors, experimental evidence suggests that a minimum of 10 repeats is necessary for TAL effector activity [3]. TAL effector genes encoding fewer repeats likely exist as remnants of, or raw material for, adaptations in TAL effector gene content through recombination.

Delivery of TAL effectors into plant cells takes place through the bacterial type III secretion system within hours of inoculation, via an N terminal type III secretion signal [18]. Once in the host cell, TAL effectors localize to the nucleus via nuclear localization signals located C-terminal to the repeat region. The repeat region then directs binding to specific host DNA sequences. When bound to a gene promoter, TAL effectors activate transcription of that gene via an acidic activation domain located at the extreme C-terminus of the protein. Many TAL effectors activate susceptibility (S) genes, whose expression facilitates bacterial multiplication and spread, or results in disease symptoms, or both [1, 2] (Figure 2). TAL effector AvrBs3, from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria (a pepper pathogen) targets the transcription factor and cell size regulator gene UPA20. The cell hypertrophy triggered by UPA20 activation is hypothesized to contribute to bacterial exudation to the leaf surface, allowing for dissemination [19, 20]. Several Xanthomonas oryzae TAL effectors target a family of genes encoding sugar exporters known as SWEET proteins [21-24]. Inducing expression of these genes would shunt energy-rich photosynthate into the extracellular space and make it available for consumption by the bacteria [25], though this explanation has not yet been tested experimentally. In addition to UPA20, at least one other host transcription factor gene, OsTFX1 in rice, is targeted by a TAL effector important for virulence (PthXo6 of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae) indicating that individual TAL effector contributions may involve broad and indirect alterations to host transcription [26].

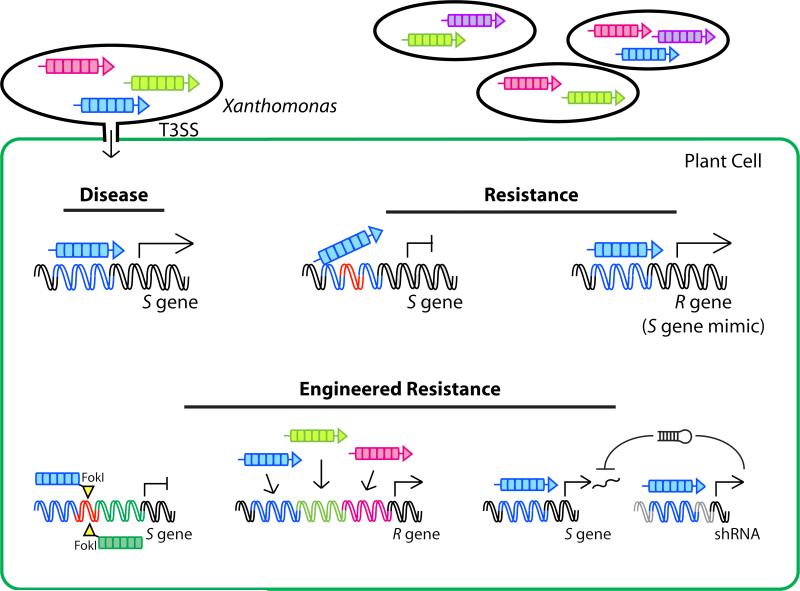

Figure 2. TAL effectors in plant disease, natural disease resistance, and engineered resistance.

Following delivery into the host plant cytoplasm via the bacterial type III secretion system (T3SS) and translocation to the nucleus, TAL effectors bind to RVD-specified sequences in host DNA (matched colors). Binding leads to the activation of host susceptibility (S) genes, top left, that contribute to disease. Resistant plants may harbor an S gene promoter mutation, top middle (red DNA), that blocks binding and activation by the TAL effector, or they may harbor an S gene mimic called an executor resistance (R) gene, top right, that has a TAL effector binding site in its promoter but encodes a protein that mediates localized cell death and limits the infection when activated. Strategies for engineered resistance to pathogens that depend on TAL effectors as virulence factors include, bottom left, site-directed mutagenesis (red DNA) of TAL effector binding sites in major S genes using engineered nucleases such as TALENs (see also Figure 3); bottom middle, R genes with an artificial promoter containing multiple TAL effector binding sites so that pathogen loss of a single effector will not make the gene ineffective, and so the gene can be effective against diverse strains; and bottom right, an S gene silencing construct consisting of a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) driven by one or more TAL effectors. In this last example, the context (grey DNA) for the TAL effector binding site in the silencing construct should be different from that of the S gene to avoid silencing any endogenous expression of the S gene in the absence of the TAL effector.

Plants have evolved resistance mechanisms to thwart TAL effector-wielding pathogens (Figure 2). These mechanisms include adaptations that prevent key S genes from being activated. The rice resistance gene xa13 is an allele of the major S gene SWEET11 that harbors a short deletion in its promoter that destroys the binding site for the corresponding TAL effector PthXo1 [21]. Rice resistance gene xa5 encodes the gamma subunit of the general transcription factor TFIIA but harbors a mutation that results in a single amino acid substitution. This substitution is thought to disrupt the presumed association of TAL effectors with host transcriptional machinery, and prevent activation of S genes [27]. Resistance mechanisms also include S gene mimics, in which a TAL effector target site resides in the promoter of a so-called “executor resistance (R) gene” [1]. Activation of such genes (including Bs3 and Bs4c in pepper and Xa27 in rice) by corresponding TAL effectors results in localized host cell death and prevents infection [28-30]. In yet another form of resistance, the Xanthomonas campestris TAL effector AvrBs4 is recognized prior to nuclear import by the cytoplasmic host protein Bs4, and this recognition triggers a plant immune response [31].

Though the distribution of TAL effectors in nature appears largely confined to Xanthomonas, TAL effector-like proteins are found in another plant pathogenic bacterium, the soil borne species Ralstonia solanacearum. These Ralstonia TAL like-effectors (RTLs) harbor repeats of 35 amino acids and contain RVDs rarely or not observed in Xanthomonas. The RTL repeats, artificially substituted into a Xanthomonas TAL effector, mediate specific DNA recognition, with target sites corresponding to their RVD sequence [32]. Recently, wildtype RTLs were shown to be active on artificial promoters [33]. The specificity of RTL RVDs that differ from a Xanthomonas RVD only in the 12th position are generally consistent with what one would predict from Xanthomonas structures, strongly suggesting a conserved overall protein topology. However, the proteins have a strong preference for G rather than T preceding the RVD-specified target [33]. No RTL-targeted genes have been identified, so the role of these proteins in plant disease remains unknown. Nonetheless, RTLs from a collection of strains were observed to have less diversity than TAL effectors in the repeat region, suggesting that engineered, RTL-triggered resistance could be broadly effective against Ralstonia solancearum [33].

TAL effectors and improving plant disease resistance

Discovery of the TAL-DNA binding code is advancing not only our understanding of TAL effector-dependent mechanisms in disease and defense, but also our ability to identify new sources of resistance. For example, knowledge of S genes allows breeders to search for alternate alleles that lack the TAL effector binding site. New S gene candidates can be identified by scanning promoters of all genes in a plant genome for matches to TAL effectors important for virulence [34] and selecting from among those matched genes that are upregulated during infection. These candidates can then be tested individually for dependence of their expression on the corresponding effector, and for their role in disease. Genome wide predictions combined with TAL effector dependent expression data can also expedite molecular identification of new executor R genes when the corresponding TAL effector is known [35].

TAL-DNA code can also be used to engineer new types of resistance (Figure 2). Identification of TAL effector binding sites in S gene promoters has enabled targeted mutagenesis of these sites (e.g., by using engineered nucleases; see next section) to generate plants that resist infection [36]. However, such resistance may not prove to be durable; it could be overcome by the evolution of an alternative TAL effector that binds to the new promoter or to an alternate S gene. Likewise, executor R genes might be broken by pathogen loss or modification of the activating TAL effector. For more durable resistance, binding sites for multiple TAL effectors might be added to an executor R gene promoter, selecting sites for TAL effectors that are important for virulence. This site stacking strategy can also broaden the specificity of an R gene. For example, it was used to generate rice plants resistant to multiple strains of two pathogenic variants of Xanthomonas oryzae [37]. However, that same study showed that TAL effector binding sites likely overlap endogenous cis regulatory elements; adding such elements to the promoter of a cell death-triggering executor R gene could cause unintended activation under unforeseeable conditions, leading to aborted development or death of the plant [37]. Therefore, alternative strategies should also be explored. One possibility is a TAL effector-activated S gene silencing construct. Using a promoter identical to that of the S gene to drive expression of the silencing construct might seem like a desirable failsafe against evolution of alternate TAL effectors that activate the S gene, but it could be problematic since it would lead to silencing of any endogenous expression of the S gene. Instead, one could use an alternate promoter that shares only the TAL effector binding site and has a non-overlapping endogenous expression pattern, such as that of a collateral target of the TAL effector. To overcome such resistance, bacterium would need to simultaneously acquire a loss of function mutation to avoid triggering the silencing construct and a gain of function mutation to target a different sequence in the S gene promoter. Since at least one S gene, OsSWEET14 in rice, is targeted by distinct TAL effectors in different strains [23, 24], such retargeting is conceivable. Stacking the silencing construct with other R genes, or, as with the stacked R gene promoter discussed above, inserting binding sites for additional TAL effectors into the promoter of the silencing construct would further guard against this.

TAL effectors as customizable DNA targeting proteins

Fusions for targeted gene activation and repression

TAL effectors can be easily targeted to desired DNA sequences by assembling the corresponding sequence of repeats (Box 1). Custom TAL effectors have been shown to be effective for targeted gene activation in a variety of cell types, often increasing gene expression by more than 20-fold. In plant cells, high levels of gene activation have been achieved using the native TAL effector activation domain [38]. In human and other mammalian cells, activation of target genes was highest when the native activation domain was replaced by the VP16 activation domain from herpes simplex virus or its tetrameric derivative VP64 [39, 40]. Similarly, targeted gene repression in plant and animal cells has been achieved using custom TAL effectors in which the activation domain is replaced by a repressor domain, or, in yeast, when it is simply removed [41-43]. Custom TAL effectors (as activators) can fail in the face of epigenetic silencing of the target locus [44], though as described in the structure section above, substituting NG for HD should accommodate cytosine methylation. Despite this limitation, TAL effector-based gene regulation has potential in synthetic biology, in which the ability to tightly control components of novel genetic circuits is critical [41, 45]. TAL effector-based gene activators and repressors may also be useful for treating diseases related to gene expression defects. In a proof of concept study, a custom TAL effector was used to increase transcription of the human frataxin gene. Low expression of frataxin causes Friedreich ataxia, a disease characterized by progressive nervous system damage [46].

TAL effector fusions for genome editing

Custom TAL effector domains were rapidly adopted to create sequence specific nucleases – so-called TAL effector nucleases or TALENs [47, 48]. A TALEN comprises a TAL effector repeat array that recognizes a specific target sequence, fused to the catalytic domain of the endonuclease FokI. FokI functions as a dimer, so two TAL effector arrays are engineered to bind sites on opposing strands of DNA that are separated by a short spacer (typically 15-20 bp). The binding of TAL effector domains brings FokI monomers into proximity, resulting in DNA cleavage within the spacer sequence. The double strand break (DSB) activates cellular DNA repair pathways, which can be harnessed to achieve desired DNA sequence modifications at or near the break site (Figure 3).

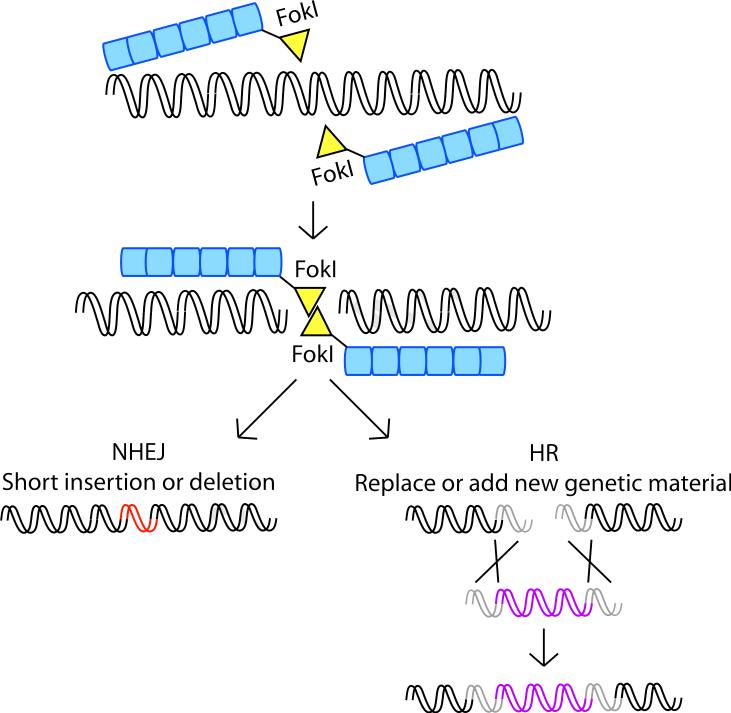

Figure 3. TALEN-mediated genome editing.

Double strand breaks introduced by TALENs are repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), leading to short insertions or deletions, or by homologous recombination (HR), which can be used to replace or insert new DNA. TALENs are shown as TAL effector fusions to the catalytic domain of the type IIS restriction endonuclease FokI, which cuts as a dimer.

Non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), which involves the rejoining of broken ends of the chromosome, is one of the primary means by which DSBs are repaired in eukaryotes [49-51]. NHEJ is sometimes imprecise, and occasionally small deletions or insertions are introduced at the break site. If imprecise repair of a TALEN-induced DSB occurs in a coding sequence, mutations are introduced that can knock out gene function. Alternatively, if two or more breaks are introduced simultaneously in the genome, then a variety of chromosomal rearrangements can result, including large-scale deletions, inversions or translocations. Targeted mutagenesis achieved through NHEJ can be used to study gene function, to create organisms or cell lines with genetic defects for use as disease models, or potentially to inactivate deleterious genes in the context of cell therapy or crop or livestock improvement.

Another means by which DSBs can be repaired is through homologous recombination (HR), also referred to as gene targeting [49-51]. HR is achieved by introducing a DNA fragment encoding a variant of a sequence of interest into cells. Once in the cell, HR between the incoming DNA and the native locus at the cut site results in an exchange of genetic information, thereby incorporating sequence alterations at the locus. Sequence alterations can range from single base pair substitutions to large DNA insertions. The diversity of DNA sequence modifications enabled by HR, as well as the ability to target DSBs to any chromosomal locus, provides unprecedented control over genetic material in a variety of organisms.

The field of targeted genome modification using TALENs has advanced rapidly since the first TALENs were reported three years ago [47, 48]. Whereas the TAL effector repeat array mediates DNA recognition, sequences flanking the array (the so-called TALEN backbone) also influence TALEN activity in vivo. Although targeted chromosome breaks can be achieved using TALEN backbones that include most or all of the N- and C-terminal regions flanking the DNA binding domain [47, 48], several groups reported enhanced activity for TALENs with truncations of the N- and C-termini [14, 15, 52]. For example, truncated backbone architectures in plants result in more than a 25-fold increase in mutagenesis of endogenous targets [53]. We speculate that removal of N- and C-terminal sequences stabilizes or facilitates folding of the TALEN protein to improve expression and activity.

In the short time since the first TALENs were reported, they have proven powerful reagents for reverse genetics in multiple experimental systems. Although not comprehensive, the pantheon of experimental models whose genome has been manipulated by TALENs already includes C. elegans [54], Drosophila [55], zebrafish [56], Xenopus [57], mice [58], rats [59], and various plant [48, 60, 61] and livestock species [62]. TALEN-mediated genome modification has been accomplished in human differentiated cell lines [14] as well as embryonic stem and induced pluripotent stem cells [63]. They are rapidly being employed to ameliorate genetic diseases through gene therapy and to solve challenges in agriculture [36, 52, 62, 64-66].

A potential alternative approach for genome editing is using TAL effector targeted recombinases. Recombinases (e.g. Cre) mediate recombination between specific DNA recognition sites (e.g. LoxP) and enable a diverse array of genome modifications including deletions, insertions and inversions. TAL effector recombinases (“TALER”s) have recently been engineered to recognize novel sites in genomes and thereby obviate the need to integrate recognition sites such as LoxP [67].

Despite the growing popularity of TAL effector based tools for genome editing, particularly TALENs, a newly developed platform based on the bacterial CRISPR/Cas system for defense against phage may have significant relative advantages. This system relies on a guide RNA to direct the Cas9 nuclease to cleave a target DNA sequence [68]. Where TALENs consist of two large proteins that must be independently constructed and expressed together to target sequences flanking a desired cut site, Cas9 functions as a monomer, and a CRISPR/Cas9 expression construct, once generated, must only be modified with a 20 bp insert in the RNA coding element to target a new gene [69]. Another advantage of the CRISPR/Cas9 system is that multiple targets can be encoded into a single guide RNA [69, 70]. The CRISPR/Cas9 system has been used to mediate HR and NHEJ in human and mouse cells, with activity comparable to or better than that of TALENs [69, 70]. Targeting specificity of this system, however, has not yet been examined in depth. CRISPR/Cas9 targeting depends on RNA-DNA hybridization across 20 base pairs and the presence of an NGG motif immediately downstream; TALENs typically target from 30-40 bases (15-20 bases per monomer) and may provide a specificity advantage, critical for example in therapeutic applications.

Concluding remarks

Although custom TAL effectors and TALENs have proven to be powerful tools for a variety of applications, challenges and questions remain. Custom TAL effector-based constructs function with varying degrees of efficiency. Despite modularity of the repeats, as noted above, RVDs differ in their apparent affinities for their preferred nucleotides. Thus, variation may simply relate to RVD (and target site) composition. Effects of binding site context and chromatin status, still largely unexplored, may also play a significant role. Better understanding of these effects combined with the identification of high affinity RVDs or repeat types that could be used to replace those with lower affinities will be necessary to maximize and standardize the efficiency of TAL effectors and TALENs.

In addition to affinity, specificity is also important, and sometimes critical. In nature, all known TAL effector and target alignments contain positions where an RVD associates with a non-preferred nucleotide, and most contain one or a few RVDs that lack specificity. This degeneracy may be the product of selection for a binding mechanism that can accommodate minor genetic changes in the host before adaptation through effector recombination restores optimal binding. Whether this degeneracy is based in evolution or simple biochemistry, it presents a challenge for designing custom TAL effector-based DNA targeting proteins with perfect specificity, even when using the most specific RVDs. There is some evidence that TAL effector tolerance for mismatches varies depending on the type, position, and context of the mismatch, but this tolerance has not been studied systematically, making it difficult to predict off-targeting. Activity at off-target sites has been documented for both custom TAL effectors and TALENs [15, 71, 72]. Overall, TAL effectors appear to target with very good specificity [reviewed in 7]. But for applications such as human disease therapy, absolute specificity is paramount [65]. Better understanding of mismatch tolerance, and continued identification of any additional RVDs that can be used to replace less stringent ones, such as NH in place of NN for guanine, will aid in designing highly specific constructs [9, 43].

Because of their large size and repeat structure, delivery and integrity of TAL effector proteins or expression constructs might present a challenge, depending on cell type or method. For viral delivery of TAL expression constructs to mammalian cells, for example, size may be limiting. The repeats might also render constructs unstable. Advances in protein and nucleic acid delivery are an important technical frontier for further improving the utility of TAL effector-based DNA targeting tools. For TALENs, the use of a monomeric nuclease domain would decrease complexity [73]. Where possible, incorporating a nuclease domain with inherent specific DNA binding properties might also reduce the number of repeats needed, allowing smaller constructs.

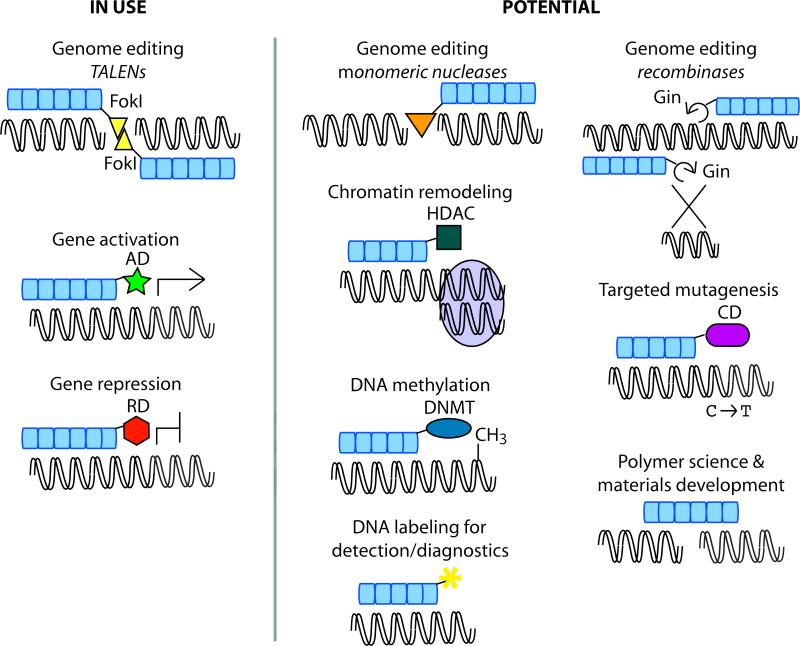

Another future challenge is the continued development of new TAL effector-based tools (Figure 4). Closest on the horizon are probably TAL effector targeted DNA methylases (or demethylases) and histone modifiers for chromatin remodeling, and targeted cytosine deaminases or other mutagens for single base pair editing without recombination. One could also imagine using TAL effectors for DNA labeling or diagnostics, or even as organic linker molecules for DNA based materials [74].

Figure 4. Applications of custom TAL effectors.

FokI, FokI endonuclease catalytic domain. AD, activation domain. RD, repressor domain. HDAC, histone deacytelase. DNMT, DNA methyltransferase. Gin, Gin recombinase. CD, cytosine deaminase.

Questions about native TAL effectors also remain. Determining their evolutionary origins and the selective forces acting on them may shed light on their uneven distribution across Xanthomonas species, and their limited distribution outside Xanthomonas. Probing the diversity and functions of TAL effector activated S and R genes is essential to expand our knowledge of disease and defense mechanisms, and to exploit that knowledge for effective disease control. Advances in both fields of inquiry into natural TAL effectors will at the same time advance our understanding of TAL effector DNA interaction and our ability to continue to use that understanding in creative and robust ways to investigate and manipulate cell biology.

Doyle et al., TAL effectors – Highlights.

Recent literature concerning transcription activator-like (TAL) effectors is reviewed

TAL effectors are plant bacterial virulence factors that activate host genes

DNA sequence recognition by TAL effectors is structurally encoded and customizable

Understanding roles of TAL effectors opens avenues for engineered plant resistance

TAL effector-based DNA targeting is advancing research, biotechnology, and medicine

Box 1. Design and assembly of custom TAL effector constructs.

Several online tools that aid users in designing custom TAL effectors and TALENs are freely available, including ZiFiT (http://zifit.partners.org/ZiFiT/Introduction.aspx), Mojo Hand (http://www.talendesign.org/mojohand_main.php), and TALE-NT 2.0 (https://talent.cac.cornell.edu) [34, 75, 76]. For construction, modular assembly methods that rely on Golden Gate cloning have been developed that enable individual researchers to make dozens of constructs in a few days [32, 40, 61, 71, 77]. Reagents for many of these methods are available as kits from the non-profit plasmid repository Addgene (www.addgene.org). Solid state synthesis methods that allow high throughput, automatable assembly of custom TAL effector constructs have also been developed [78-80]. Custom TAL effectors and TALENs are available commercially as well.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bogdanove AJ, et al. TAL effectors: finding plant genes for disease and defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010;13:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boch J, Bonas U. Xanthomonas AvrBs3 family-type III effectors: Discovery and function. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2011;48:419–436. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boch J, et al. Breaking the code of DNA binding specificity of TAL-type III effectors. Science. 2009;326:1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1178811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moscou MJ, Bogdanove AJ. A simple cipher governs DNA recognition by TAL effectors. Science. 2009;326:1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1178817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mak AN-S, et al. The crystal structure of TAL effector PthXo1 bound to its DNA target. Science. 2012;335:716–719. doi: 10.1126/science.1216211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng D, et al. Structural basis for sequence-specific recognition of DNA by TAL effectors. Science. 2012;335:720–723. doi: 10.1126/science.1215670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF. TAL effectors: customizable proteins for DNA targeting. Science. 2011;333:1843–1846. doi: 10.1126/science.1204094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Web of Knowledge. Thomson Reuters; Feb 3, 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Streubel J, et al. TAL effector RVD specificities and efficiencies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:593–595. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christian ML, et al. Targeting G with TAL effectors: a comparison of activities of TALENs constructed with NN and NK repeat variable di-residues. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murakami MT, et al. The repeat domain of the type III effector protein PthA shows a TPR-like structure and undergoes conformational changes upon DNA interaction. Proteins. 2010;78:3386–3395. doi: 10.1002/prot.22846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng D, et al. Recognition of methylated DNA by TAL effectors. Cell Res. 2012;22:1502–1504. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin P, et al. Specific DNA-RNA hybrid recognition by TAL effectors. Cell Reports. 2012;2:707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller JC, et al. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:143–148. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mussolino C, et al. A novel TALE nuclease scaffold enables high genome editing activity in combination with low toxicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9283–9293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao H, et al. Crystal structure of a TALE protein reveals an extended N-terminal DNA binding region. Cell Res. 2012;22:1716–1720. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scholze H, Boch J. TAL effectors are remote controls for gene activation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011;14:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makino S, et al. Inhibition of resistance gene-mediated defense in rice by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006;19:240–249. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wichmann G, Bergelson J. Effector genes of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. vesicatoria promote transmission and enhance other fitness traits in the field. Genetics. 2004;166:693–706. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.2.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gurlebeck D, et al. Visualization of novel virulence activities of the Xanthomonas type III effectors AvrBs1, AvrBs3 and AvrBs4. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009;10:175–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00519.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang B, et al. Os8N3 is a host disease-susceptibility gene for bacterial blight of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10503–10508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604088103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verdier V, et al. Transcription activator-like (TAL) effectors targeting OsSWEET genes enhance virulence on diverse rice (Oryza sativa) varieties when expressed individually in a TAL effector-deficient strain of Xanthomonas oryzae. New Phytol. 2012;196:1197–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu Y, et al. Colonization of rice leaf blades by an African strain of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae depends on a new TAL effector that induces the rice nodulin-3 Os11N3 gene. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2011;24:1102–1113. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-11-10-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antony G, et al. Rice xa13 recessive resistance to bacterial blight is defeated by induction of the disease susceptibility gene Os11N3. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3864–3876. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L-Q, et al. Sucrose efflux mediated by SWEET proteins as a key step for phloem transport. Science. 2012;335:207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.1213351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugio A, et al. Two type III effector genes of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae control the induction of the host genes OsTFIIA gamma 1 and OsTFX1 during bacterial blight of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:10720–10725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701742104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iyer AS, McCouch SR. The rice bacterial blight resistance gene xa5 encodes a novel form of disease resistance. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2004;17:1348–1354. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.12.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Römer P, et al. Plant pathogen recognition mediated by promoter activation of the pepper Bs3 resistance gene. Science. 2007;318:645–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1144958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu K, et al. R gene expression induced by a type-III effector triggers disease resistance in rice. Nature. 2005;435:1122–1125. doi: 10.1038/nature03630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strauss T, et al. RNA-seq pinpoints a Xanthomonas TAL-effector activated resistance gene in a large-crop genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:19480–19485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212415109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schornack S, et al. The tomato resistance protein Bs4 is a predicted non-nuclear TIR-NB-LRR protein that mediates defense responses to severely truncated derivatives of AvrBs4 and overexpressed AvrBs3. Plant J. 2004;37:46–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L, et al. Characterization and DNA-binding specificities of Ralstonia TAL-like effectors. Mol. Plant. 2013 doi: 10.1093/mp/sst006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Lange O, et al. Breaking the DNA binding code of Ralstonia solanacearum TAL effectors provides new possibilities to generate plant resistance genes against bacterial wilt disease. New Phytol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/nph.12324. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doyle EL, et al. TAL Effector-Nucleotide Targeter (TALE-NT) 2.0: tools for TAL effector design and target prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W117–W122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strauss T, et al. RNA-seq pinpoints a Xanthomonas TAL-effector activated resistance gene in a large-crop genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:19480–19485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212415109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li T, et al. High-efficiency TALEN-based gene editing produces disease-resistant rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:390–392. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hummel AW, et al. Addition of transcription activator-like effector binding sites to a pathogen strain-specific rice bacterial blight resistance gene makes it effective against additional strains and against bacterial leaf streak. New Phytol. 2012;195:883–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morbitzer R, et al. Regulation of selected genome loci using de novo-engineered transcription activator-like effector (TALE)-type transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21617–21622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013133107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geissler R, et al. Transcriptional activators of human genes with programmable DNA-specificity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang F, et al. Efficient construction of sequence-specific TAL effectors for modulating mammalian transcription. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:149–153. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blount BA, et al. Rational diversification of a promoter providing fine-tuned expression and orthogonal regulation for synthetic biology. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahfouz M, et al. Targeted transcriptional repression using a chimeric TALE-SRDX repressor protein. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012;78:311–321. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9866-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cong L, et al. Comprehensive interrogation of natural TALE DNA-binding modules and transcriptional repressor domains. Nature Commun. 2012;3:968. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bultmann S, et al. Targeted transcriptional activation of silent oct4 pluripotency gene by combining designer TALEs and inhibition of epigenetic modifiers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5368–5377. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garg A, et al. Engineering synthetic TAL effectors with orthogonal target sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:7584–7595. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tremblay JP, et al. TALE proteins induced the expression of the frataxin gene. Hum. Gene Ther. 2012;23:883–890. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Christian M, et al. Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases. Genetics. 2010;186:757–761. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.120717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li T, et al. TAL nucleases (TALNs): hybrid proteins composed of TAL effectors and FokI DNA-cleavage domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:359–372. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanaar R, et al. Molecular mechanisms of DNA double strand break repair. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:483–489. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puchta H. The repair of double-strand breaks in plants: mechanisms and consequences for genome evolution. J. Exp. Bot. 2005;56:1–14. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hartlerode AJ, Scully R. Mechanisms of double-strand break repair in somatic mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 2009;423:157–168. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun N, et al. Optimized TAL effector nucleases (TALENs) for use in treatment of sickle cell disease. Molecular BioSystems. 2012;8:1255–1263. doi: 10.1039/c2mb05461b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, et al. Transcription activator-like effector nucleases enable efficient plant genome engineering. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:20–27. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.205179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wood AJ, et al. Targeted genome editing across species using ZFNs and TALENs. Science. 2011;333:307. doi: 10.1126/science.1207773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu J, et al. Efficient and specific modifications of the Drosophila genome by means of an easy TALEN strategy. J. Genet. Genomics. 2012;39:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sander JD, et al. Targeted gene disruption in somatic zebrafish cells using engineered TALENs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:697–698. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lei Y, et al. Efficient targeted gene disruption in Xenopus embryos using engineered transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17484–17489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215421109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sung YH, et al. Knockout mice created by TALEN-mediated gene targeting. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:23–24. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tesson L, et al. Knockout rats generated by embryo microinjection of TALENs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:695–696. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mahfouz MM, et al. De novo-engineered transcription activator-like effector (TALE) hybrid nuclease with novel DNA binding specificity creates double-strand breaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:2623–2628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019533108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cermak T, et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carlson DF, et al. Efficient TALEN-mediated gene knockout in livestock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17382–17387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211446109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hockemeyer D, et al. Genetic engineering of human pluripotent cells using TALE nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:731–734. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Porteus M. Year in Human and Medical Genetics: Inborn Errors of Immunity Ii. Blackwell Science Publ; 2011. Homologous recombination-based gene therapy for the primary immunodeficiencies. pp. 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Humbert O, et al. Targeted gene therapies: tools, applications, optimization. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012;47:264–281. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2012.658112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schiffer JT, et al. Targeted DNA mutagenesis for the cure of chronic viral infections. J. Virol. 2012;86:8920–8936. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00052-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mercer AC, et al. Chimeric TALE recombinases with programmable DNA sequence specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11163–11172. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jinek M, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mali P, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morbitzer R, et al. Assembly of custom TALE-type DNA binding domains by modular cloning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:5790–5799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dahlem TJ, et al. Simple methods for generating and detecting locus-specific mutations induced with TALENs in the zebrafish genome. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kleinstiver BP, et al. Monomeric site-specific nucleases for genome editing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:8061–8066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117984109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roh YH, et al. Engineering DNA-based functional materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:5730–5744. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15162b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sander JD, et al. ZiFiT (Zinc Finger Targeter): an updated zinc finger engineering tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W462–W468. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Neff KL, et al. Mojo hand, a TALEN design tool for genome editing applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weber E, et al. Assembly of designer TAL effectors by golden gate cloning. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang Z, et al. An integrated chip for the high-throughput synthesis of transcription activator-like effectors. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2012;51:8505–8508. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reyon D, et al. FLASH assembly of TALENs for high-throughput genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:460–465. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Briggs AW, et al. Iterative capped assembly: rapid and scalable synthesis of repeat-module DNA such as TAL effectors from individual monomers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]