ERECTA family receptors are involved in the regulation of phyllotaxy and leaf initiation.

Abstract

Leaves are produced postembryonically at the flanks of the shoot apical meristem. Their initiation is induced by a positive feedback loop between auxin and its transporter PIN-FORMED1 (PIN1). The expression and polarity of PIN1 in the shoot apical meristem is thought to be regulated primarily by auxin concentration and flow. The formation of an auxin maximum in the L1 layer of the meristem is the first sign of leaf initiation and is promptly followed by auxin flow into the inner tissues, formation of the midvein, and appearance of the primordium bulge. The ERECTA family genes (ERfs) encode leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinases, and in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), this gene family consists of ERECTA (ER), ERECTA-LIKE1 (ERL1), and ERL2. Here, we show that ERfs regulate auxin transport during leaf initiation. The shoot apical meristem of the er erl1 erl2 triple mutant produces leaf primordia at a significantly reduced rate and with altered phyllotaxy. This phenotype is likely due to deficiencies in auxin transport in the shoot apex, as judged by altered expression of PIN1, the auxin reporter DR5rev::GFP, and the auxin-inducible genes MONOPTEROS, INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID INDUCIBLE1 (IAA1), and IAA19. In er erl1 erl2, auxin presumably accumulates in the L1 layer of the meristem, unable to flow into the vasculature of a hypocotyl. Our data demonstrate that ERfs are essential for PIN1 expression in the forming midvein of future leaf primordia and in the vasculature of emerging leaves.

Leaves are formed during postembryonic development by the shoot apical meristem (SAM), a dome-shaped organ with a stem cell reservoir at the top and with leaf initiation taking place slightly below in the peripheral zone. The initiation of leaf primordia depends on the establishment of auxin maxima at the site of initiation (Braybrook and Kuhlemeier, 2010). Auxin is polarly transported through the epidermal layer of the meristem to the incipient primordium initiation site (Heisler et al., 2005) and then moves inward, where it promotes the formation of a vascular strand (Scarpella et al., 2006; Bayer et al., 2009). The developing vascular tissue acts as an auxin sink, depleting auxin in the epidermal layer (Scarpella et al., 2006). PIN1, an auxin efflux protein, is a central player in the formation of auxin maxima and is involved in the transport of auxin in both the epidermis and the forming vascular strand during leaf initiation (Benková et al., 2003; Reinhardt et al., 2003). PIN1 is the earliest marker for midvein formation (Scarpella et al., 2006), which starts to form before a leaf primordium bulges out of the meristem. The mechanisms determining PIN1 expression and polar localization in the SAM are central to understanding leaf initiation. In the L1 layer of the SAM, PIN1 is polarly localized in the plasma membrane toward cells with higher auxin concentration (Jönsson et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2006). Formation of the vein is explained by the canalization hypothesis, in which high auxin flux reinforces PIN1 expression (Kramer, 2008). Of all plasma membrane-localized PIN family transporters, only PIN1 has been detected in the vegetative SAM and linked with the initiation of rosette leaves (Guenot et al., 2012). At the same time, rosette leaves are positioned nonrandomly in pin1 mutants, suggesting that additional PIN1-independent mechanisms also have a role in regulating leaf initiation (Guenot et al., 2012).

Here, we investigate the role of ERECTA family receptor-like kinases during leaf initiation in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). Previously, ERECTA family genes (ERfs) have been shown to be involved in the regulation of epidermis development and of plant growth along the apical-basal/proximodistal axis in aboveground organs (Torii et al., 1996; Shpak et al., 2004, 2005). Triple erecta (er), erecta-like1 (erl1), and erl2 mutants (er erl1 erl2) form a rosette with small, round leaves that lack petiole elongation. During the reproductive stage, the main inflorescence stem exhibits striking elongation defects and reduced apical dominance. ER has been implicated in vascular development, with the er mutation causing radial expansion of xylem (Ragni et al., 2011) and premature differentiation of vascular bundles (Douglas and Riggs, 2005). Recently, the dwarfism of described mutants was attributed to the function of ERf genes in the phloem, where they perceive signals from the endodermis (Uchida et al., 2012a). In the epidermis, all three genes inhibit the initial decision of protodermal cells to become meristemoid mother cells (Shpak et al., 2005). In addition, ERL1 and to a lesser extent ERL2 are important for maintaining cell proliferative activity in stomata lineage cells and for preventing terminal differentiation of meristemoids into guard mother cells. The activity of ERf receptors in the epidermis is regulated by a different set of peptides than in the phloem. EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR1 (EPF1) and EPF2 are expressed in stomatal precursor cells. They inhibit the development of new stomata in the vicinity of a forming stoma (Hara et al., 2007, 2009; Hunt and Gray, 2009). EPF-LIKE9 (EPFL9)/stomagen is expressed in the mesophyll, and, in contrast, it promotes the development of stomata (Kondo et al., 2010; Sugano et al., 2010). EPFL4 and EPFL6/CHALLAH are expressed in the endodermis, and their perception by phloem-localized ERfs is critical for stem elongation (Uchida et al., 2012a).

While ERfs are very strongly expressed in the vegetative SAM and in forming leaf primordia, only recently has it become clear that these genes are involved in the regulation of meristem size and leaf initiation (Uchida et al., 2012b, 2013). It was suggested that ERfs regulate stem cell homeostasis in the SAM via buffering its cytokinin responsiveness by an unknown mechanism (Uchida et al., 2013). Here, we further investigate the involvement of ERfs in the control of leaf initiation and phyllotaxy. Our data suggest that ERfs are essential for PIN1 expression in the vasculature of forming leaf primordia. Based on analysis of the DR5rev::GFP reporter, auxin may accumulate in the L1 layer of the SAM in the mutant but is not able to move into the vasculature, consistent with drastically reduced PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP expression there. These data suggest that the convergence of PIN1 expression in the inner tissues of the SAM during leaf initiation is a complex process involving intercellular communications enabled by ERfs. The importance of ERfs for efficient auxin transport is further supported by reduced phototropic response in the er erl1 erl2 mutant.

RESULTS

ERfs Are Critical for the Initiation of Leaf Primordia and the Establishment of Phyllotaxy

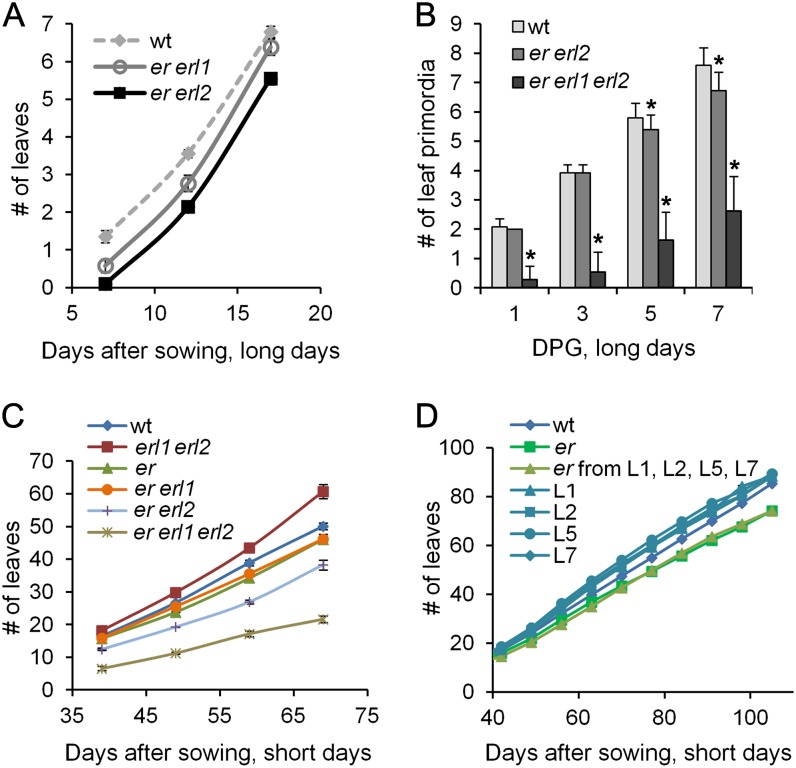

ERfs are expressed in the vegetative SAM and in leaf primordia (Yokoyama et al., 1998; Uchida et al., 2013). Previously, a quantitative trait locus analysis suggested that ER regulates total leaf number (El Lithy et al., 2004, 2010), and based on an analysis of scanning electron microscope images, it was proposed that the number of formed leaves is decreased in the er erl1 erl2 mutant (Uchida et al., 2012b). In addition, down-regulation of the ERf signaling pathway in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) by a dominant negative version of ER resulted in reduced leaf formation (Villagarcia et al., 2012). To explore ERf function in leaf initiation in more detail and to obtain quantitative data, we analyzed single, double, and triple mutants of ERf genes under long- and short-day conditions. Under long-day conditions, no change in the leaf formation rate in erl1, erl2, er, and erl1 erl2 mutants was detected; however, er erl1 and especially er erl2 formed leaves at a slower rate (Fig. 1A). The smaller number of visible leaves in the mutants could be due to a reduction in primordia initiation or to a decreased growth rate of the formed primordia or both. To address the underlying cause of the reduced visible leaf number, we analyzed the structure of SAMs during early seedling development in er erl2 and er erl1 erl2 mutants. This experiment detected a very small but statistically significant decrease in leaf initiation in the er erl2 mutant at day 5 (P < 0.01; based on Student’s t test here and below) and at day 7 (P < 0.0001) post germination (Fig. 1B). In addition, in er erl2, we observed decreased longitudinal primordia growth from day 1 to day 3 (Supplemental Fig. S1). While at day 1 there was no significant difference between the size of the first true leaves in the wild type and er erl2, from day 1 to day 3 these leaves increased in size 3.17 times on average in the wild type versus 2.67 times in er erl2. Thus, the reduced number of visible leaves in the er erl2 mutant is likely caused by both a slight reduction in leaf primordia initiation and a reduced rate of leaf elongation. The change in leaf primordia initiation was much more dramatic in the er erl1 erl2 mutant (Fig. 1B). While all of the wild-type and er erl2 seedlings had formed at least two leaf primordia by day 1 post germination, most of the er erl1 erl2 seedlings (72%) did not have a single primordium and 28% had only one tiny primordium. On day 3, a majority of the wild-type and er erl2 seedlings had four primordia, whereas 54% of er erl1 erl2 seedlings did not have any, 36% had one, and 10% had two.

Figure 1.

ERf genes regulate the rate of leaf formation. A, The rate of leaf formation in er erl1 and er erl2 mutants is decreased compared with the wild type (wt). Plants were grown under long-day conditions. Values are means ± sd for 31 to 34 plants. B, The rate of leaf primordia initiation is dramatically reduced in er erl1 erl2 as determined by DIC microscopy of fixed samples. A primordium was defined as a bulge over 15 μm. DPG, Days post germination. Values are means ± sd for 22 to 25 plants. Values significantly different from the control are indicated by asterisks (P < 0.05). C, The rate of leaf formation in ERf mutants is decreased compared with the wild type, except for erl1 erl2 plants, where it is increased. Plants were grown under short-day conditions. D, The reduced rate of leaf formation is rescued by the ERpro:ER construct in the er mutant. Leaf formation was analyzed in the wild type, er, and T2 families derived from four independent transgenic lines: in plants that received the construct (L1, L2, L5, and L7) from the parental heterozygous plant and in plants that did not (er from L1, L2, L5, and L7). In C and D, values are means ± se for 22 to 24 plants. Error bars were added to A, C, and D, but due to their small size they are not visible for some data points.

Since changes in the rate of leaf formation are easier to detect when plants are grown in short days, we also observed our mutants under those conditions. We did not detect a novel phenotype in the single erl1 and erl2 mutants, but er mutants formed leaves at a slightly slower rate (Fig. 1C). To check whether this phenotype could be rescued by the ERpro:ER construct (Godiard et al., 2003), we analyzed the rate of leaf formation in short days in segregated T2 families derived from four independent transgenic lines. All four transgenic lines contained a single ERpro:ER insertion in the er background. Plants containing the construct were easily identified at maturity based on the length of pedicels and siliques and on plant height. In all four lines, we observed that the rate of leaf formation in er plants with the ERpro:ER construct increased to the wild-type levels (Fig. 1D). Analysis of double mutants in short days demonstrated that the addition of the erl2 mutation to er further decreased the rate of leaf formation, while the addition of erl1 did not (Fig. 1C). The phenotype was most severe in the triple er erl1 erl2 mutant, with leaves appearing approximately 2.4 times slower compared with the wild type. Interestingly, erl1 erl2 mutants formed leaves at a faster rate than the wild type. Based on these mutant phenotypes, we conclude that all three receptors help to control leaf formation in short days, with ER being more effective than ERL1 and ERL2. The increased leaf formation rate in the erl1 erl2 mutant may be due to improved efficiency of ER in the absence of ERL1 and ERL2, as it does not need to compete with the other receptors for ligands or other components of the signaling pathway.

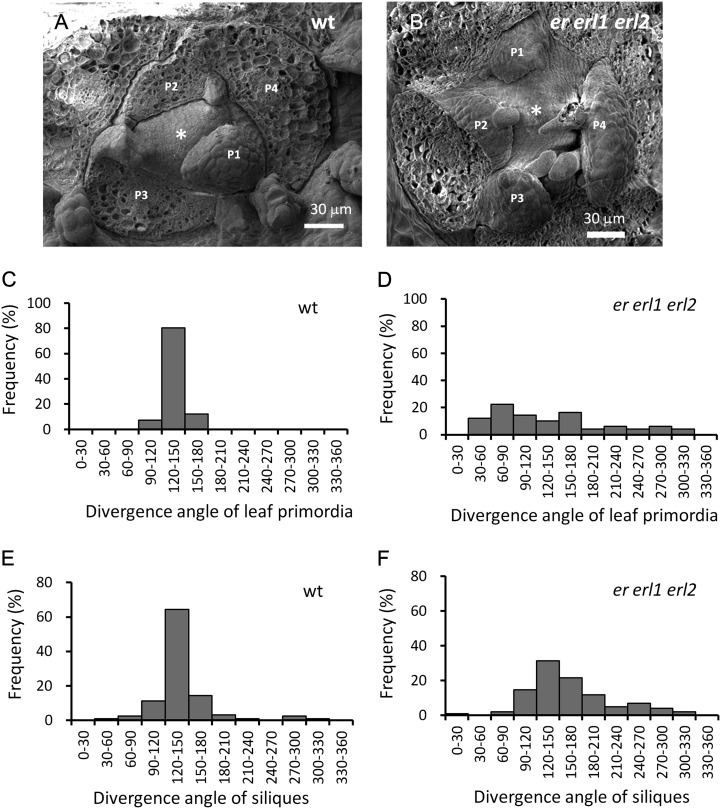

To determine whether ERf genes are important for the establishment of phyllotaxy, we attempted to measure leaf divergence angles in er erl1 erl2 seedlings grown in soil. However, due to very short petioles and the altered shape of leaf blades in the mutant, this approach did not provide reliable data. We then examined leaf phyllotaxy directly in shoot apices using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). This experiment demonstrated that leaf primordia divergence angles in er erl1 erl2 mutants strongly deviated from the 137° found in the wild-type plants (Fig. 2, A–D). While in the wild type, new leaf primordia appeared consecutively and as far as possible from already formed primordia, in er erl1 erl2, primordia often formed almost simultaneously immediately adjacent to each other. Measurement of divergent angles between successive siliques along the main inflorescence stem also demonstrated differences in phyllotactic patterning between the wild type and the er erl1 erl2 mutant (Fig. 2, E and F). In er erl1 erl2, we observed decreased stability of the phyllotactic pattern, with an increased number of flower primordia forming at angles significantly different from 137°. In the mutant, only 31% of flower primordia formed at the angle between 120o and 150°, while in the wild type, 64% did. The average divergence angles of flower primordia were 138.0° ± 3.1° (±se; n = 126) in the wild type and 159.0° ± 5.5° (±se; n = 102) in the mutant. Thus, ERf receptors are essential for the establishment of leaf phyllotaxy, and they contribute strongly to the phyllotactic patterning of flower primordia.

Figure 2.

ERf genes are important for the establishment of phyllotaxy, as evident from an analysis of the er erl1 erl2 mutant. A and B, SEM images of SAMs of wild-type (wt; A) and er erl1 erl2 (B) seedlings. Note the abnormal leaf positioning in er erl1 erl2. Asterisks designates the SAM, and P1 to P4 indicate bulging leaf primordia, with a smaller number corresponding to a younger primordium. In er erl1 erl2, the age of a primordium is determined by its size and level of epidermis differentiation. Older primordia covering SAMs were removed. C and D, The frequency of divergence angle between two successive leaf primordia in wild-type (C; n = 41) and er erl1 erl2 (D; n = 49) seedlings. E and F, The frequency of divergence angle between two successive siliques in wild-type (E; n = 126) and er erl1 erl2 (F; n = 102) inflorescences.

ERf Genes Regulate the Size of the SAM

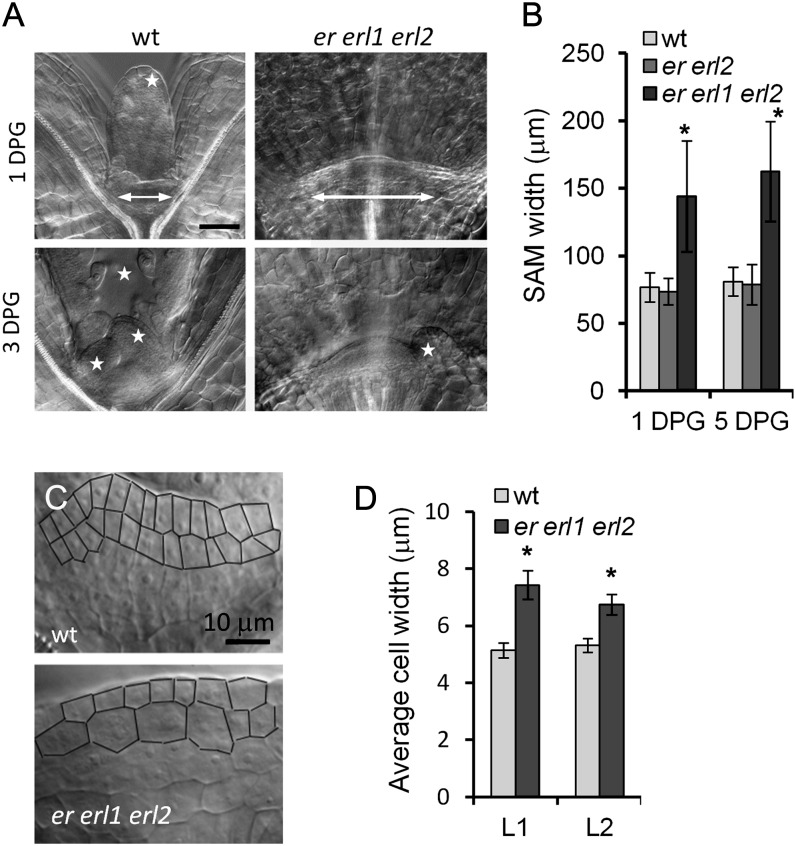

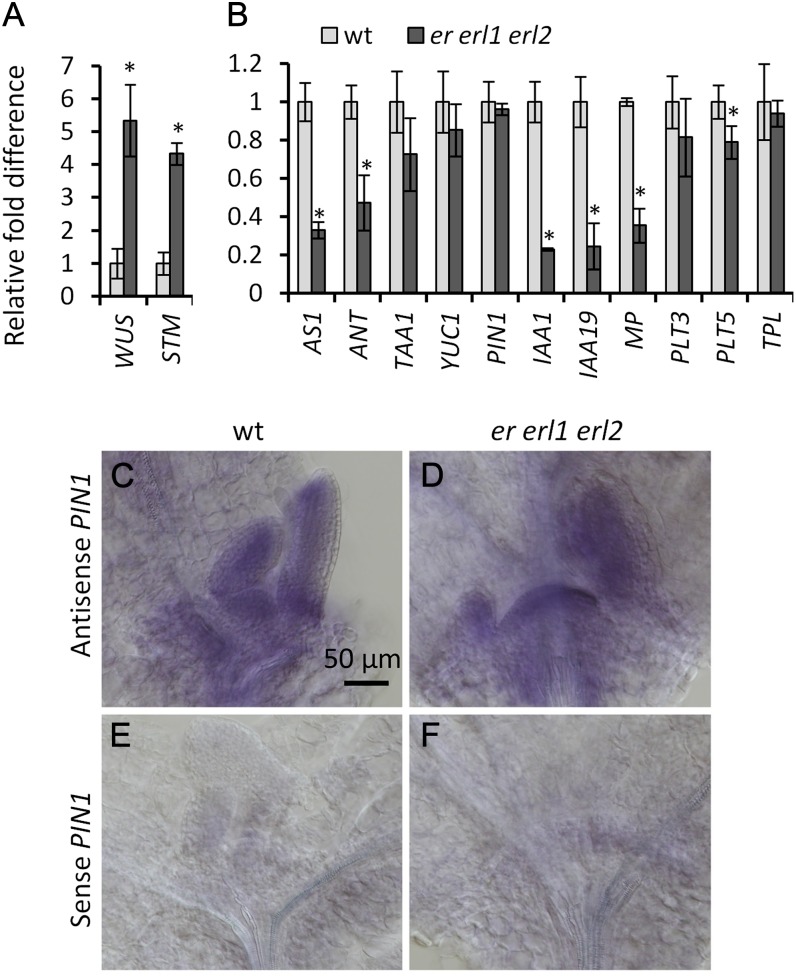

The formation of a leaf primordium requires a sufficient number of founder cells, and reduced leaf initiation could be related to decreased meristem size. However, this is not the case for the er erl1 erl2 mutant. Recent work suggests that at day 9, er erl1 erl2 mutants have flatter and broader meristems (Uchida et al., 2013). To obtain quantitative data at earlier developmental stages, we analyzed meristem size at day 1 and day 5 post germination. In both cases, we observed that the meristem in er erl1 erl2 is approximately two times broader compared with either the wild type or er erl2 (Fig. 3, A and B). This result is consistent with the timing of ERf expression in the shoot meristematic region. Analysis of ER, ERL1, and ERL2 promoter-GUS fusions demonstrated that ERf genes are not expressed in mature dry seeds or in seeds imbibed in water before germination (Supplemental Fig. S2, A–C), but their expression becomes noticeable during testa rupture in shoot and root meristematic regions (Supplemental Fig. S2, D–F). During the next 24 h, the expression of all three ERf genes dramatically increases in the SAM and in forming leaf primordia (Supplemental Fig. S2, G–I and M–R). This up-regulation of ERf gene expression during germination is not dependent on light, as a similar pattern of expression was detected in etiolated seedlings (Supplemental Fig. S2, J–L). The increased size of SAMs in er erl1 erl2 is linked with raised expression of WUSCHEL (WUS) and SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM; Fig. 4A), key regulators of meristem development (Ha et al., 2010). At the same time, we observed decreased expression of ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 (AS1; Fig. 4B), a MYB transcription factor involved in the specification of cotyledons and leaves (Byrne et al., 2000), and of AINTEGUMENTA (ANT), a gene expressed in the incipient leaf primordia (Long and Barton, 2000). A closer look at the meristemic region in er erl1 erl2 mutants demonstrated that cells in the L1 and L2 layers were significantly wider (Fig. 3, C and D); thus, while er erl1 erl2 meristems were twice as broad, the number of cells in the L1 and L2 layers was only moderately increased. Therefore, the increase of the er erl1 erl2 SAM size cannot be caused solely by increased cell proliferation due to WUS overexpression or by decreased incorporation of cells into leaf primordia.

Figure 3.

The SAM size and the width of L1 and L2 cells in the SAM are increased in the er erl1 erl2 mutant. A, DIC images of meristematic regions in the wild type (wt) and er erl1 erl2. The meristem width is displayed with an arrow. Visible primordia are labeled with stars. On the wild-type images, one primordium is out of focus and not visible. Images are under the same magnification. DPG, Days post germination. Bar = 50 μm. B, Comparison of the SAM width. Values are means ± sd for 22 to 25 seedlings. C, Closeup DIC images of meristematic regions in the wild type and er erl1 erl2 at 3 d post germination. The cell walls in the L1 and L2 layers are traced for better visualization. Both images are under the same magnification. Bar = 10 μm. D, Average width of cells ± sd in L1 and L2 layers of the SAM in wild-type and er erl1 erl2 seedlings (n = 6) at 1 d post germination. In B and D, values significantly different from the control are indicated by asterisks (P < 0.005).

Figure 4.

Analysis of gene expression in er erl1 erl2. A and B, Real-time RT-PCR analysis of selected genes in 5-d-old wild-type (wt) and er erl1 erl2 seedlings excluding root tissues. The average of three biological replicates is presented. Error bars represent sd. Values significantly different from the control are indicated by asterisks (P < 0.05). C to F, In situ analysis of PIN1 expression in the SAMs of wild-type (C and E) and er erl1 erl2 (D and F) seedlings using antisense (C and D) or sense (E and F) PIN1 RNA probes did not detect any difference in expression pattern. All images are under the same magnification.

YODA and a GSK3-Like Kinase Function Downstream of ERfs in the SAM

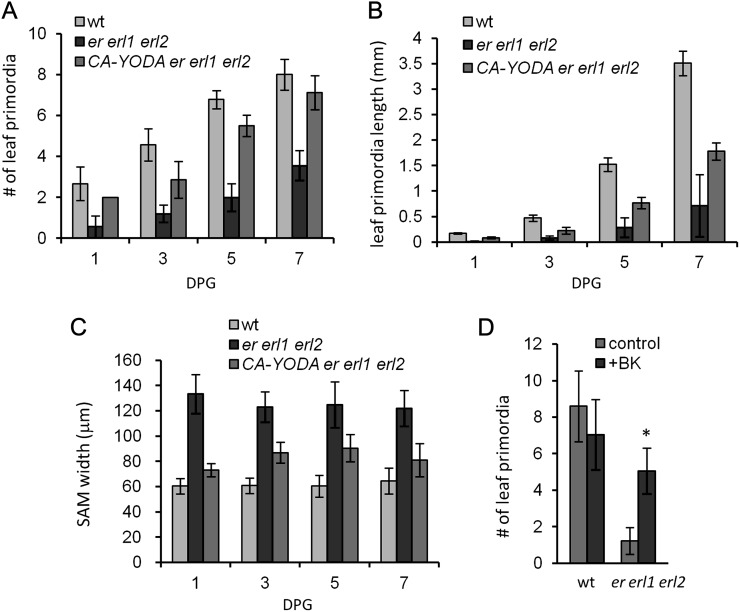

A mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade consisting of YODA, MKK4, MKK5, MPK3, and MPK6 functions downstream of ERf receptors, regulating both stomata development and growth along the proximal/distal axis (Bergmann et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2007; Meng et al., 2012). To investigate whether ERfs use the same signaling cascade in the meristem during leaf initiation, we analyzed the ability of CONSTITUTIVELY ACTIVE YODA (CA-YODA; Lukowitz et al., 2004) to rescue the SAM defects of the er erl1 erl2 mutant. Expression of CA-YODA in the mutant increased leaf primordia initiation and their growth rate (Fig. 5, A and B) and decreased the size of the meristem (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

CA-YODA and bikinin rescue leaf initiation in er erl1 erl2. A to C, Expression of CA-YODA increases the rate of primordia formation (A) and leaf primordia elongation (B) and decreases meristem width in er erl1 erl2 (C). Values are means ± sd for 22 to 25 seedlings. DPG, Days post germination. In A to C, all er erl1erl2 values are significantly different from the wild type (wt; P < 0.01); all CA-YODA er erl1 erl2 values are significantly different from er erl1 erl2 (P < 0.01). D, Increased leaf primordia initiation in 8-d-old seedlings grown on 30 μm bikinin. Values are means ± sd for 18 to 23 seedlings. The value significantly different from the control is indicated by an asterisk (P < 0.001).

Recently, it was proposed that a GSK3-like kinase can module the ERf signaling pathway (Gudesblat et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2012). One of the experiments supporting this conclusion demonstrated the ability of bikinin, a highly specific inhibitor of GSK3-like kinases, to rescue the stomata-clustering phenotype of the er erl1 erl2 mutant (Kim et al., 2012). We found that treatment of er erl1 erl2 with bikinin can also partially rescue leaf initiation (Fig. 5D). Unfortunately, it was not possible to measure meristem size, as bikinin treatment changed the meristem shape from dome to concave in both wild-type seedlings and the mutant, and we were not able to clearly define the meristematic zone. Together, these experiments suggest that in the SAM, the signal from ERfs is transduced by a mechanism similar to that during epidermis development or plant elongation along the proximal/distal axes.

Auxin Distribution Is Abnormal in er erl1 erl2 Seedlings

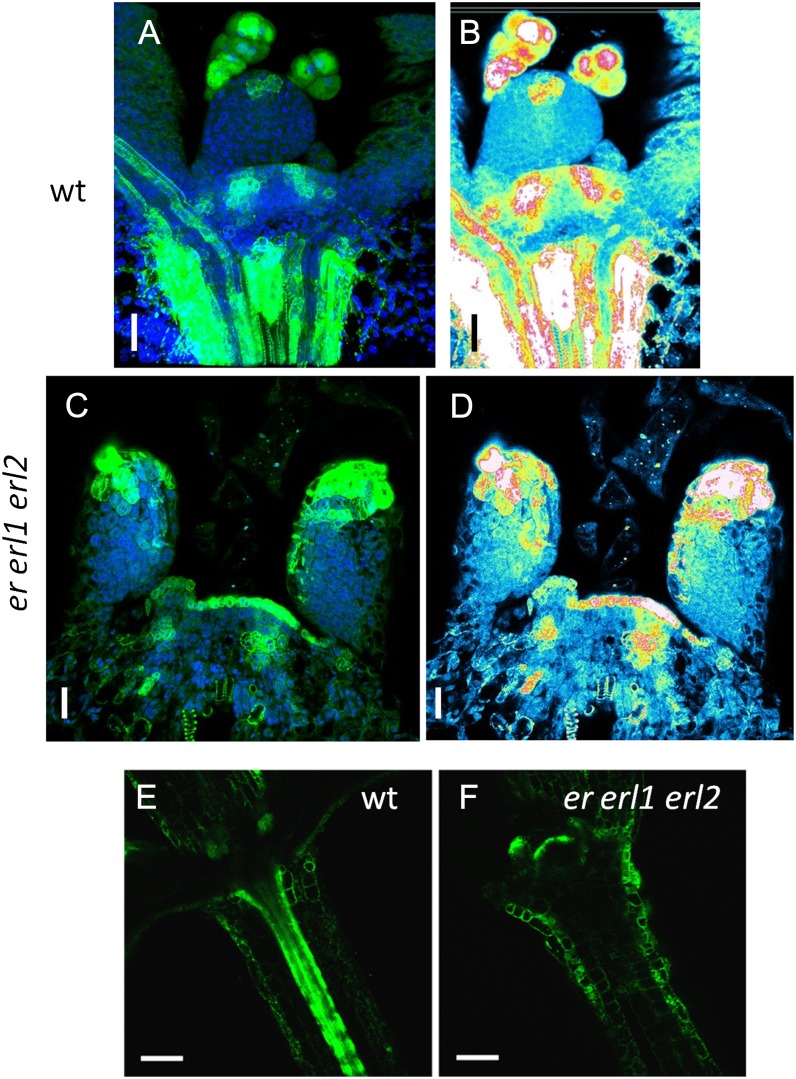

The formation of an auxin maximum in the meristem is the first sign of new leaf primordium initiation. To determine the distribution of auxin in the meristematic region of er erl1 erl2 mutants, we observed the expression of DR5rev::GFP, where the enhanced GFP (eGFP) protein is targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum (Friml et al., 2003). In the wild-type vegetative SAM, the DR5rev::GFP signal was observed to form maxima in the L1 layer and directly below in the internal tissues (Fig. 6, A and B). In er erl1 erl2, we observed very high expression of DR5rev::GFP in the L1 layer of the meristem but no maxima formation (Fig. 6, C and D). A spotted expression of DR5rev::GFP was sometimes noticed in the internal tissues of the SAM, but it did not form well-defined stripes as in the wild type. In addition, DR5rev::GFP expression differed in formed leaf primordia. In the wild type, DR5rev::GFP was expressed at the tips of incipient primordia in a very limited region of the L1 layer (Fig. 6, A and B), while in the mutant, the expression at the tips was much broader (Fig. 6, C and D). But the most dramatic difference of DR5rev::GFP expression was observed in the vasculature of hypocotyls, where this construct was very highly expressed in the wild type but not in the mutant (Fig. 6, E and F). Since the formation of auxin maxima in the meristem and auxin flow onto the vasculature are critical for leaf initiation (Braybrook and Kuhlemeier, 2010), the observed abnormalities in auxin distribution in er erl1 erl2 should be unfavorable for efficient leaf initiation.

Figure 6.

Auxin distribution, as determined by the activity of the synthetic auxin response element DR5, is abnormal in er erl1 erl2. In the wild type (wt), the DR5rev:GFP signal is detected in the SAM in areas of presumptive leaf primordia initiation, at tips of leaf primordia, and in vasculature (A, B, and E). In er erl1 erl2, the DR5rev:GFP construct is expressed broadly in the L1 layer of the meristem, including its center (C and D). The expression at the tips of the forming primordia is broader, but it is absent from the vasculature (C, D, and F). A, C, E, and F are confocal images with GFP signal in green. In A and C, the DAPI signal is in blue. B and D are semiquantitative color-coded heat maps, with blue indicating low intensity and red indicating high intensity. Bars = 20 μm in A to D and 100 μm in E and F.

The changed distribution of auxin in er erl1 erl2 correlates with drastically reduced expression of the auxin-inducible genes MONOPTEROS (MP), IAA1, and IAA19 (Fig. 4B). However, we were unable to detect substantial changes in the expression of enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of auxin. The conversion of Trp to indole-3-acetic acid with the help of TAA1/WEI8 (for TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE OF ARABIDOPSIS1/WEAK ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE8) and YUCCA (YUC) enzymes is a main biosynthetic pathway in auxin production (Stepanova et al., 2008, 2011; Tao et al., 2008) and is essential for leaf primordia formation (Cheng et al., 2007). WEI8/TAA1 encodes a Trp aminotransferase responsible for the conversion of Trp into indole-3-pyruvate in the first step of Trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis (Stepanova et al., 2008; Tao et al., 2008). In the wild type and in the mutant, our analysis detected similar expression of the TAA1pro:GFP-TAA1 construct in the SAM and in the margins of leaf primordia (Supplemental Fig. S3). Consistent with this, real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis demonstrated similar levels of YUC1 in the wild type and er erl1 erl2 and only a very slight decrease of TAA1 expression in er erl1 erl2 (Fig. 4B). In addition, the expression of PLETHORA3 (PLT3) and PLT5, transcription factors involved in the regulation of auxin biosynthesis (Pinon et al., 2013), was only very slightly reduced in er erl1 erl2 (Fig. 4B). We did, however, observe higher WUS expression in the mutant (Fig. 4A). WUS inhibits auxin signaling; specifically, it promotes the expression of TOPLESS (TPL), a corepressor of auxin signaling (Szemenyei et al., 2008; Busch et al., 2010). However, we did not observe any change in TPL expression in er erl1 erl2 (Fig. 4B). Thus, we conclude that while ERfs regulate the distribution of auxin in the SAM, they do not have a substantial impact on auxin biosynthesis.

ERfs Are Essential for PIN1 Expression in the Vasculature of Leaf Primordia

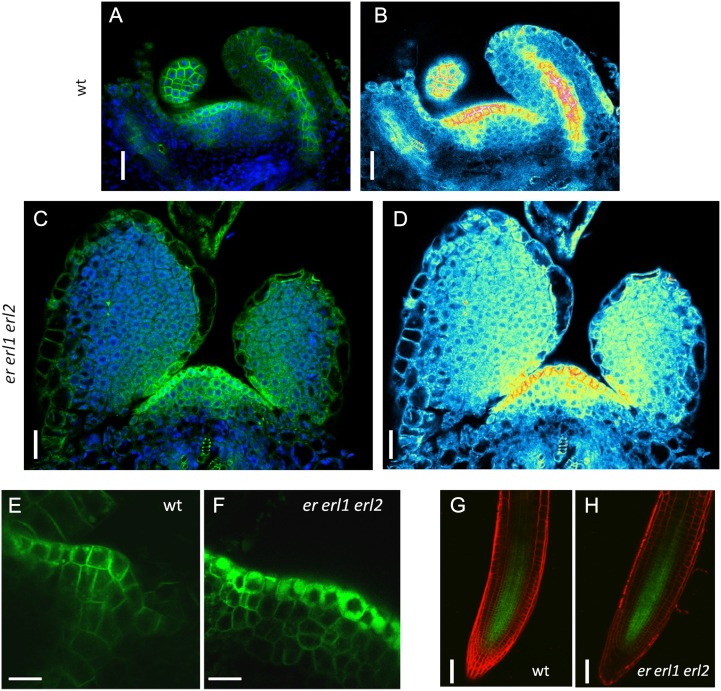

As auxin distribution in the SAM is critically dependent on the PIN1 auxin transporter, we investigated the expression of the PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP construct (Benková et al., 2003). In the wild-type SAM, we observed PIN1 expression in the L1 layer and in the subepidermal provascular tissue directly beneath forming leaf primordia (Fig. 7, A, B, and E), as published previously (Heisler et al., 2005). The PIN1-GFP fusion protein was mostly localized in the plasma membrane (Fig. 7E). However, some of it was present in small round vesicles that are presumably vacuoles (Marhavý et al., 2011). In the er erl1 erl2 mutants, the PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP construct was more highly expressed in the L1 layer of the SAM compared with the wild type (Fig. 7, E and F). Most of the protein was localized in presumed vacuoles, but it was also present in the plasma membrane. Quantification of PIN1-GFP subcellular accumulation in L1 layer cells demonstrated that a similar number of PIN1-GFP molecules reaches the plasma membrane in the wild type and in er erl1 erl2. The measurements also confirmed increased cytoplasmic accumulation of PIN1-GFP (Supplemental Fig. S4). We speculate that the increased accumulation of PIN1 in L1 layer vacuoles might be a consequence of PIN1 overexpression. In the plasma membrane of L1 cells in the er erl1 erl2 mutant, we also often observed polar localization of PIN1-GFP (Supplemental Fig. S4B). PIN1 was present in the plasma membrane of subepidermal cells in the meristem; however, the expression was broad, and no canalization of PIN1 expression was observed (Fig. 7, C, D, and F). Another difference was dramatically reduced PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP expression in the vasculature of forming er erl1 erl2 leaves (Fig. 7, B and D; Supplemental Fig. S5). At the same time, the expression of PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP in the vasculature of roots was not altered (Fig. 7, G and H). We did not observe any change in PIN1 mRNA accumulation (Fig. 4, B–F), suggesting that ERf genes might regulate PIN1 protein localization and stability. The patterns of DR5rev::GFP and PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP expression in the er erl1 erl2 mutant imply that ERfs are involved in the regulation of auxin flow in the SAM and into incipient organ primordia.

Figure 7.

In the er erl1 erl2 mutant, PIN1 is absent from the leaf primordium vasculature and is mislocalized in the SAM. A to D, In the internal layers of the wild-type (wt) meristem, PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP expression is limited to the place of incipient leaf primordia formation (A and B), while in the er erl1 erl2 mutant (C and D), no such confinement is observed. PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP expression was also absent from leaf primordia vasculature in the mutant (compare A and B with C and D). E and F, While the construct is expressed in the L1 layer of the meristem in both the wild type (E) and er erl1 erl2 (F), the levels of expression and subcellular localization are different. G and H, Identical expression of PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP in roots of the wild type (G) and er erl1 erl2 (H). In A, C, and E to H, the GFP signal is in green. In A and C, the DAPI signal is in blue. In G and H, cell walls were stained with FM4-64 (red). B and D are semiquantitative color-coded heat maps, with blue indicating low intensity and red indicating high intensity. Bars = 20 μm in A to D, 10 μm in E and F, and 50 μm in G and H.

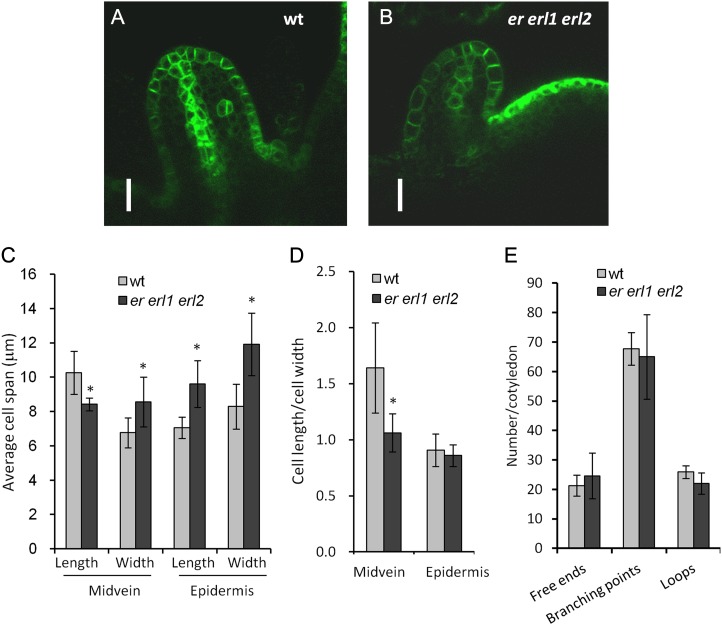

An analysis of free ends, branching points, and loops formed by vasculature in mature first and second leaves suggested that ERf genes do not have an obvious effect on leaf vascular pattern formation (Fig. 8E). But does the reduced flow of auxin correlate with any changes in early procambium development? To answer this question, we analyzed the shape of cells in the forming midvein of similarly sized young leaf primordia (Fig. 8, A and B). The identity of midvein cells was determined by PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP expression, which can be detected in most er erl1 erl2 leaf primordia by increasing the sensitivity of GFP detection (Fig. 8B). In the wild type, cells in the forming midvein were elongated in the longitudinal direction, but in the mutant, they lost the directionality of expansion, becoming nearly round (Fig. 8, C and D). This result suggests a role for ERfs during the very early steps of vasculature differentiation. We also observed changes in the behavior of L1 cells in er erl1 erl2 leaf primordia. These cells expand mostly periclinally, and ERfs do not control that direction of expansion (Fig. 8, C and D). But the increased size of L1 cells in the er erl1 erl2 mutant suggests that ERfs are involved in the regulation of the cell cycle in the L1 layer of leaf primordia. A similar increase in the size of L1 layer cells was observed in the SAM (Fig. 3D).

Figure 8.

ERf genes are important for longitudinal cell elongation in the developing midvein. A and B, Confocal images of PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP expression in young leaf primordia. The image in B was taken with higher sensitivity. Bars = 20 μm. C, Average span of midvein and epidermis cells in young leaf primordia of the wild type (wt) and er erl1 erl2. Six to 17 cells in midvein or in epidermis were measured in six to eight primordia. D, Average ratio of cell length to cell width for midvein and epidermis cells in young leaf primordia. In C and D, values significantly different from the control are indicated by asterisks (P < 0.02). E, No differences in the general pattern of veins of mature first or second rosette leaf (n = 10) were detected in er erl1 erl2. In C to E, error bars represent sd.

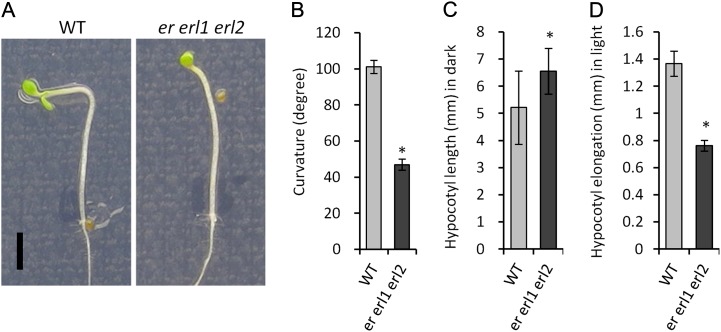

Phototropic Bending in er erl1 erl2

Phototropic bending of hypocotyls depends on asymmetric auxin transport (Went and Thimann, 1937; Ding et al., 2011). Because our analysis of DR5rev::GFP expression indicated that ERfs are essential for efficient auxin transport into hypocotyls, we speculated that phototropic responses might be affected in er erl1 erl2. Analysis of the response of seedlings to unilateral white light confirmed that the bending of er erl1 erl2 hypocotyls was severely impaired (Fig. 9, A and B). Auxin transport is also important for hypocotyl elongation in light-grown but not in dark-grown seedlings (Jensen et al., 1998). While the elongation of er erl1 erl2 hypocotyls was slightly but statistically significantly increased over the wild type during growth in darkness (P < 0.005), after transition to light, it decreased approximately 2-fold (Fig. 9, C and D). These data indirectly support the hypothesis that ERfs are involved in the regulation of auxin transport during photomorphogenesis.

Figure 9.

Phototropism and light-dependent hypocotyl elongation are impaired in er erl1 erl2. A, Phototropic response of wild-type (WT) and er erl1 erl2 hypocotyls. Seedlings were grown for 3 d in darkness and then for 24 h in unidirectional white light. Both images are under the same magnification. Bar = 2 mm. B, Hypocotyl curvature after 24 h of unilateral light illumination. C, Hypocotyl length after 3 d of growth in darkness. D, Hypocotyl elongation after 24 h of unilateral white light illumination. In B to D, n = 13 to 15 and error bars represent sd. Values significantly different from the control are indicated by asterisks (P < 0.01). [See online article for color version of this figure.]

DISCUSSION

ERfs Regulate Multiple Developmental Processes, including Leaf Initiation

Receptor-like kinases (RLKs) form the largest class of membrane receptors that, in addition to classical plant hormones, play fundamental roles in plant growth and development (Morillo and Tax, 2006). The ability of RLKs to perceive diverse extracellular signals and transmit them through the plasma membrane enables cell-to-cell communications that are necessary for coordinated cell proliferation and differentiation. Like classical hormones, a single RLK can regulate a variety of growth and developmental processes. For example, the RLK FERONIA mediates pollen tube rupture in the female gametophyte (Escobar-Restrepo et al., 2007) as well as root hair elongation (Duan et al., 2010). The RLK SCRAMBLED/STRUBBELIG regulates the shape of flower organs, ovule development (Chevalier et al., 2005), leaf patterning (Lin et al., 2012), and also controls the specification of epidermal root hairs (Kwak et al., 2005).

The ERfs constitute another group of RLKs that is involved in the regulation of different aspects of plant development (van Zanten et al., 2009). In addition to their function in the phloem and epidermis, ERf receptors promote integument growth (Pillitteri et al., 2007), regulate anther differentiation (Hord et al., 2008), and promote adaxial leaf identity (Xu et al., 2003). Here, we investigated the role of ERf genes in the vegetative SAM during leaf initiation. Analysis of leaf formation in various ER family mutants suggested that all three receptors synergistically regulate phyllotaxy and the rate of leaf initiation, with ER playing the major role, just as in the regulation of stem elongation (Shpak et al., 2004). During short days, we observed both decreased (in er, er erl1, er erl2, and er erl1 erl2) and increased (in erl1 erl2) rates of leaf initiation in the mutants, suggesting that the ERf signaling pathway is not only mechanistically necessary for leaf initiation but that it might also be used to adjust the timing of this process. Unfortunately, it is not possible to investigate this further in ER overexpression lines, as such transgenic plants are phenotypically indistinguishable from the wild type, possibly due to posttranscriptional regulation of ER expression (Karve et al., 2011) or because the signaling is limited by some other component.

ERfs Are Necessary for PIN1 Expression in Incipient Leaf Vasculature

The plant hormone auxin is central for organ initiation by the SAM, regulating the rate of their formation (plastochron) and their arrangement on the stem (phyllotaxy). A decrease in either auxin transport or auxin biosynthesis reduces the rate of organ initiation (Lohmann et al., 2010; Guenot et al., 2012). Earlier studies of single er mutants did not detect a direct effect of ER on auxin homeostasis, but they did uncover an increased sensitivity of er plants to auxin (Woodward et al., 2005). Transcriptome analysis suggested that ER might promote the growth of the inflorescence via the modulation of auxin signaling (Uchida et al., 2012a). Speculating that redundancy in ERf gene function might have prevented an earlier elucidation of ERf’s role in auxin biosynthesis or distribution, we analyzed those processes in the triple mutant.

Our data point to the importance of ERfs for auxin transport in the shoot apical meristem and suggest that abnormal phyllotaxy and reduced leaf primordia initiation in the er erl1 erl2 mutant might be related to inadequate accumulation of auxin into maxima in the L1 layer and to poor transport of auxin into forming midveins of incipient leaf primordia. In the mutant, PIN1 is severely down-regulated in the vasculature of forming leaf primordia. Consistent with this, the expression patterns of DR5rev::GFP and TAA1pro:GFP-TAA1 in er erl1 erl2 are highly similar, suggesting that while auxin is synthesized in the mutant, it is not effectively transported from the place of biosynthesis. Whereas in the wild type, auxin accumulates in the vasculature of hypocotyls, in er erl1 erl2, it is trapped in the L1 layer of the meristem, and its ability to form a maximum or move downward into the vasculature is severely decreased. This alteration of auxin distribution is consistent with a reduced expression of the auxin-inducible genes MP, IAA1, and IAA19. Moreover, phototropic bending and light-dependent hypocotyl elongation, two developmental responses dependent on auxin transport, are impaired in er erl1 erl2.

ERfs seem to regulate PIN1 expression at the posttranscriptional level; however, the mechanism of this regulation remains to be determined. To that end, it would be valuable to investigate the connection between ERfs and cytokinin signaling. Cytokinins are critical for SAM function; they promote stem cell identity at least in part through the up-regulation of WUS (Gordon et al., 2009). A reduction in cytokinin levels leads to a smaller SAM (Werner et al., 2001; Miyawaki et al., 2006; Kurakawa et al., 2007), while knockout of ABERRANT PHYLLOTAXY1 (ABPH1), a type A Arabidopsis response regulator (ARR) and a putative negative regulator of cytokinin signaling, increases meristem size (Giulini et al., 2004). Moreover, changes in cytokinin signaling affect both the plastochron and phyllotaxy (Giulini et al., 2004; Miyawaki et al., 2006). The ability of cytokinin to regulate the initiation of leaf primordia is likely related to both the impact on SAM size and on auxin transport. Cytokinins can down-regulate PIN1 by triggering its lytic degradation (Marhavý et al., 2011), and the expression of ABPH1 in the incipient leaf primordium is necessary for PIN1 expression (Lee et al., 2009). The increased size of the er erl1 erl2 meristem and the elevated expression of WUS imply an increased accumulation of cytokinins that would disrupt PIN1 expression and lead to reduced leaf initiation in the mutant. However, this conclusion is not consistent with the ability of exogenous cytokinins to rescue leaf initiation in er erl1 erl2 (Uchida et al., 2013). More detailed analyses of cytokinin biosynthesis and signaling in the mutant are needed to understand whether ERfs regulate PIN1 expression in the vasculature through the cytokinin signaling pathway or by an independent means.

The analysis of the er erl1 erl2 mutant advances our understanding of how auxin transport contributes to leaf initiation and vasculature development. First, in spite of severely disrupted auxin transport, the er erl1 erl2 mutant is able to produce leaf primordia (albeit more slowly), supporting the idea that there should be a PIN1-independent mechanism of leaf initiation (Guenot et al., 2012). Second, auxin transport into the inner layers of the meristem is believed to be a trigger for preprocambial cell selection (for review, see Scarpella and Helariutta, 2010). However, while PIN1 expression is severely reduced in veins of forming leaf primordia in er erl1 erl2 seedlings, the veins are still able to form and no significant difference in the general vein patterning is detected. Thus, there should be other triggers of preprocambial differentiation besides auxin transport.

We propose that ERf genes are essential for imparting the ability to efficiently transport auxin to the meristematic cells that form a leaf midvein. In the inflorescence stem, ERf genes are expressed in the phloem, where they regulate communication between the endodermis and phloem (Uchida et al., 2012a). While the exact outcome of this communication is unknown, ERf genes are likely to control some aspect of vasculature differentiation and growth. By analogy, ERf-enabled communications might be essential for the proper differentiation of vasculature in the meristem. Thus, our data suggest that ERfs are needed for polarized elongation of preprocambial cells, which might result from the induction of efficient auxin transport. This hypothesis needs to be further explored in mutants with reduced or enhanced auxin transport.

Role of ERfs in Meristem Maintenance

Leaf primordia form at the flanks of a SAM, and their initiation pattern depends on the size of the meristem (Hamada et al., 2000; Giulini et al., 2004). ER is known to regulate the size and function of inflorescence meristems; the er mutation enhances meristem defects in CLAVATA pathway mutants (Dievart et al., 2003; Durbak and Tax, 2011) and in the mutant of the nucleotide-binding (NB)–Leu-rich repeat-type UNI protein (Uchida et al., 2011). The decreased initiation of leaf primordia could be a side effect of decreased meristem size. However, the shoot apical meristem of the mutant is larger than the wild type; thus, in theory, there should be an adequate supply of cells that could be recruited for primordia initiation. In the er erl1 erl2 mutant, the larger meristem and reduced initiation of leaf primordia are linked with higher expression of key regulators of meristem maintenance, CLAVATA3 (CLV3), WUS, and STM, and with lower expression of AS1 and ANT, genes expressed during the initiation of leaf primordia (Uchida et al., 2013; this study). However, the role of ERf genes in the SAM seems to be different from that of the CLAVATA signaling pathway (Uchida et al., 2012b). The CLAVATA pathway regulates the stem cell niche in the meristem and prevents excessive cell proliferation (Clark et al., 1996). The clv3-2 mutation leads to the formation of a bigger dome-shaped SAM, and the leaf initiation rate is unaffected (Uchida et al., 2012b). In contrast, in the er erl1 erl2 mutant, the meristem is flatter and the leaf initiation rate is decreased. An increase in meristem size including an expansion of CLV3-expressing domains was also observed when auxin transport was inhibited in the background of mp, a mutant with reduced auxin signaling and decreased leaf initiation rate (Schuetz et al., 2008). Another common characteristic of SAM development in er erl1 erl2 and in auxin transport mutants is excessive cell elongation of L1 cells along the radial axis. A similar increase in the width of L1 cells is seen in the meristems of pin1-6 (7.0 ± 0.7 mm versus 4.8 ± 0.2 mm in the wild type; Vernoux et al., 2000) and er erl1 erl2 (7.4 ± 1.2 mm versus 5.1 ± 0.6 mm in the wild type; Fig. 3D) mutants. Therefore, the increased meristem size in er erl1 erl2 might be a direct consequence of defective leaf initiation due to abnormal auxin distribution. Alternatively, ERfs might regulate some aspect of SAM patterning that controls meristem size independently of auxin transport and leaf initiation. Here, of interest is the strong expression of DR5rev::GFP in the central zone of the SAM in er erl1 erl2, which does not occur either in the wild type or in pin1 mutants, presumably due to the low sensitivity of that tissue to auxin (Smith et al., 2006; Vernoux et al., 2011).

In conclusion, the ERf signaling pathway is involved in the processes of shoot apical meristem maintenance, leaf initiation, establishment of phyllotaxy, and phototropism. At least one of the mechanisms through which ERfs regulate those processes is the enhancement of PIN1 expression in the vasculature of forming leaf primordia and, as a consequence, the stimulation of polar auxin transport. The ERf signaling pathway is activated by extracellular ligands and, as such, must work to coordinate the development of different type of tissues/cells during meristem development. Elucidation of the nature of this communication will be most critical for understanding ERf’s function during SAM development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotype Columbia was used as the wild type. The ER family mutants have been described previously (Torii et al., 1996; Shpak et al., 2004). The transgenic plants TAA1pro:GFP-TAA1, PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP, DR5rev::GFP, and CA-YODA are described elsewhere (Benková et al., 2003; Friml et al., 2003; Lukowitz et al., 2004; Stepanova et al., 2008). These plants were crossed with er erl1/+ erl2; the er erl1 erl2 plants containing the described constructs were identified in the F2 generation based on the phenotype and the presence of GFP fluorescence. The CA-YODA er erl1 erl2 plants were identified by genotyping. To genotype erl1-2, we used the primers erl1g3659 (5′-GAGCTTGGACATATAATC-3′), erl1g4411.rc (5′-CCGGAGAGATTGTTGAAGG-3′), and JL202 (5′-CATTTTATAATAACGCTGCGGACATCTAC-3′). To genotype erl2-1, we used the primers erl2g2166 (5′-GCCTATTCCACCAATACTTG-3′) and ertj3182.rc (5′-ACAAATCTGAGAGAGTTAATGCAAAGCAG-3′) or JL202 and ertj3182.rc. To confirm the presence of CA-YODA, we used the primers YODA-g428-F (5′-CATGGTTGCCACTTCCAAAGC-3′) and YODA-g1428-R (5′-CCAAGATACACATGTCCAAAACTTCC-3′).

Plants were grown as described elsewhere (Kong et al., 2012) under an 18-h-light/6-h-dark (long days) or an 8-h-light/16-h-dark (short days) cycle at 21°C. Nine plants per pot (7 × 7 cm) and five plants per pot were grown for long-day and short-day experiments, respectively. Plants grown under short-day conditions were fertilized with approximately 0.6 g of Miracle-Gro per eight pots once every 2 weeks. To measure the number of leaves at short days, we counted the number of new visible leaves once or twice per week and placed a mark on the youngest leaf that was counted.

For the analysis of ERf family transcriptional reporters in seedlings and for the study of meristem function and leaf primordia initiation, seedlings were grown on modified Murashige and Skoog medium plates supplemented with 1× Gamborg B5 vitamins and 1% (w/v) Suc. For all experiments, seeds were stratified for 2 d at 4°C before germination. The effect of bikinin was analyzed in 8-d-old seedlings grown on plates containing 30 μm bikinin (Sigma-Aldrich).

For the measurement of phototropic bending and hypocotyl elongation, 3-d-old etiolated seedlings were photographed and then exposed to unilateral white light for 24 h and then photographed again. The angle of hypocotyl bending was measured with E-Ruler software. The identity of er erl1 erl2 seedlings segregating out in the progeny of er erl1/+ erl2 was determined 3 to 4 d later by the shape of the cotyledons. For the analysis of leaf venation patterns, free ends, branching points, and loops were quantified manually using dark-field images of cleared first or second leaves of 31-d-old seedlings.

Measurements of Phyllotaxy

Leaf primordia phyllotaxy was analyzed on SEM images of 9-d-old wild-type and 14-d-old er erl1 erl2 seedlings. Older leaf primordia were removed for better visualization of the SAM, and the angles between two successive leaf primordia were measured by ImageJ. The samples were prepared for SEM as described previously (Shpak et al., 2003). Divergent angles of siliques were measured by a homemade protractor device as described previously (Peaucelle et al., 2007).

Microscopy

To analyze leaf primordia formation in seedlings and meristem structures, samples were fixed overnight with ethanol:acetic acid (9:1 [v/v]). After fixation, samples were rehydrated with an ethanol series to 50% (v/v) ethanol and cleared in chloral hydrate solution (chloral hydrate:water:glycerol, 8:1:1 [w/v/v]). Microscopic observations were done using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics, images were obtained with a 12-megapixel cooled color DXM-1200c (Nikon) camera, and NIS-Elements BR imaging software (Nikon) was used for measurements.

To observe the GFP signal, we used a Leica TCS SP2 or a Nikon C1 confocal laser-scanning microscope. To monitor GFP and 4′,6-diamino-phenylindole (DAPI) fluorescence, we used multitracking in-frame mode. GFP was excited using a 488-nm laser line in conjunction with a 505- to 530-nm band-pass filter. DAPI was excited with a 405-nm laser line and collected using a 420- to 480-nm band-pass filter. To expose GFP expression in the shoot meristematic region of live 5- to 8-d-old seedlings, one cotyledon was removed before observations. We also observed GFP expression in 6-d-old seedlings that were fixated with 4% (v/v) formaldehyde and mounted in Prolong Gold antifade reagent containing DAPI (Molecular Probes; Ditengou et al., 2008). Semiquantitative color-coded heat maps showing high and low GFP intensity were generated with Nikon EZ-C1 software. Pixel values are rated from 0 to 4,095. During root observation, FM4-64 dye was applied at 10 μg mL−1 to visualize plasma membranes, and it was excited with a 488-nm laser line and collected using a 600- to 665-nm band-pass filter.

ERpro:GUS, ERL1pro:GUS, and ERL2pro:GUS transgenic plants have been described earlier (Shpak et al., 2004). Promoter GUS analysis was performed according to (Sessions et al., 2000) with minor modifications. The samples were fixed in cold 90% (v/v) acetone for 20 min, rinsed with cold water, vacuum infiltrated with staining buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100, 10 mm potassium ferricyanide, 10 mm potassium ferrocyanide, and 2 mm 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-glucuronic acid), and incubated in the solution overnight. After staining, samples were incubated in an ethanol:acetic acid (1:1 [v/v]) solution for over 4 h and then cleared in a chloral hydrate solution (chloral hydrate:water:glycerol, 8:1:1 [w/v/v]) overnight. DIC optics were used to observe GUS staining. At least two independent transgenic lines were analyzed for each construct. The functionality of the ER and ERL1 promoters used has been established previously (Godiard et al., 2003).

Complementary DNA Synthesis, Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis, and in Situ Hybridization

Total RNA was isolated from the aboveground tissues of 5 d-old seedlings grown on Murashige and Skoog plates using the Spectrum Plant RNA Isolation Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). The total RNA was treated with RNase-free RQ1 DNase (Promega). First-strand complementary DNA was synthesized with oligo(dT) primers using a ProtoScript M-MuLV Taq RT-PCR kit (New England Biolabs). As a control for genomic DNA contamination, we used ACTIN2 primers flanking intron-containing regions and analyzed the melt curve after PCR.

Quantitative PCR was performed with a MyiQ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) using Sso Fast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad). Each experiment contained three technical replicates of three biological replicates and was performed in a total volume of 20 µL with 5 µL of 10 times diluted first-strand reaction. Cycling conditions were as follows: 1 min at 95°C; then 50 repeats of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 54.6°C for WUS, 55.1°C for IAA1, IAA19, and MP, 56.9°C for PLT5, STM, ANT, and YUC1, 59.3°C for ACTIN2, 59.4°C for AS1, PIN1, PLT3, TAA1, and TPL, and 10 s at 72°C; followed by the melt-curve analysis. Primers used for PCR are shown in Supplemental Table S1; the cycle threshold values were calculated using the iQ5 software (Bio-Rad). The fold difference in gene expression was calculated using relative quantification by the delta-delta-Ct algorithm (2–ΔΔCt).

In situ hybridization was performed as described previously using 6-d-old seedlings and 2.0-kb PIN1 undigested sense and antisense probes (Hejátko et al., 2006). The plasmid used for in vitro transcription of PIN1 probes is described by Gälweiler et al. (1998). The images were obtained using DIC microscopy.

Arabidopsis Genome Initiative numbers for the genes discussed in this article are as follows: ACTIN2 (At3g18780), ANT (At4g37750), AS1 (At2g37630), ER (At2g26330), ERL1 (At5g62230), ERL2 (At5g07180), IAA1 (At4g14560), IAA19 (At3g15540), MP (At1g19850), PIN1 (At1g73590), PLT3 (At5g10510), PLT5 (At5g57390), STM (At1g62360), TAA1 (At1g70560), TPL (At1g15750), WUS (At2g17950), and YUC1 (At4g32540).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Leaf primordia elongation in the er erl2 mutant.

Supplemental Figure S2. Expression of transcriptional reporters of ERECTA family genes in the SAM and in forming leaf primordia after germination.

Supplemental Figure S3. Expression of TAA1 in the wild-type and the er erl1 erl2 seedlings.

Supplemental Figure S4. Comparison of PIN1 subcellular distribution in L1 layer of SAM in the wild-type and er erl1 erl2.

Supplemental Figure S5. Confocal images of PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP expression in the vasculature of leaves in the wild type and in er erl1 erl2.

Supplemental Table S1. Primer sequences used in real time RT-PCR.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anna Stepanova, Albrecht von Arnim, and Wolfgang Lukowitz for sharing with us TAA1pro:GFP-TAA1, PIN1pro:PIN1-GFP, DR5rev::GFP, and CA-YODA seeds; Anastasia Aksenova for measuring the width of cells in the meristems; and Matt Sieger for constructing the protractor device used to measure phyllotaxy.

Glossary

- SAM

shoot apical meristem

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- RT

reverse transcription

- RLK

receptor-like kinase

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- DAPI

4′,6-diamino-phenylindole

References

- Bayer EM, Smith RS, Mandel T, Nakayama N, Sauer M, Prusinkiewicz P, Kuhlemeier C. (2009) Integration of transport-based models for phyllotaxis and midvein formation. Genes Dev 23: 373–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benková E, Michniewicz M, Sauer M, Teichmann T, Seifertová D, Jürgens G, Friml J. (2003) Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell 115: 591–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann DC, Lukowitz W, Somerville CR. (2004) Stomatal development and pattern controlled by a MAPKK kinase. Science 304: 1494–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braybrook SA, Kuhlemeier C. (2010) How a plant builds leaves. Plant Cell 22: 1006–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch W, Miotk A, Ariel FD, Zhao Z, Forner J, Daum G, Suzaki T, Schuster C, Schultheiss SJ, Leibfried A, et al. (2010) Transcriptional control of a plant stem cell niche. Dev Cell 18: 849–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne ME, Barley R, Curtis M, Arroyo JM, Dunham M, Hudson A, Martienssen RA. (2000) Asymmetric leaves1 mediates leaf patterning and stem cell function in Arabidopsis. Nature 408: 967–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. (2007) Auxin synthesized by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases is essential for embryogenesis and leaf formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 2430–2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier D, Batoux M, Fulton L, Pfister K, Yadav RK, Schellenberg M, Schneitz K. (2005) STRUBBELIG defines a receptor kinase-mediated signaling pathway regulating organ development in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 9074–9079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SE, Jacobsen SE, Levin JZ, Meyerowitz EM. (1996) The CLAVATA and SHOOT MERISTEMLESS loci competitively regulate meristem activity in Arabidopsis. Development 122: 1567–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diévart A, Dalal M, Tax FE, Lacey AD, Huttly A, Li J, Clark SE. (2003) CLAVATA1 dominant-negative alleles reveal functional overlap between multiple receptor kinases that regulate meristem and organ development. Plant Cell 15: 1198–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Galván-Ampudia CS, Demarsy E, Łangowski L, Kleine-Vehn J, Fan Y, Morita MT, Tasaka M, Fankhauser C, Offringa R, et al. (2011) Light-mediated polarization of the PIN3 auxin transporter for the phototropic response in Arabidopsis. Nat Cell Biol 13: 447–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditengou FA, Teale WD, Kochersperger P, Flittner KA, Kneuper I, van der Graaff E, Nziengui H, Pinosa F, Li X, Nitschke R, et al. (2008) Mechanical induction of lateral root initiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 18818–18823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas SJ, Riggs CD. (2005) Pedicel development in Arabidopsis thaliana: contribution of vascular positioning and the role of the BREVIPEDICELLUS and ERECTA genes. Dev Biol 284: 451–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Q, Kita D, Li C, Cheung AY, Wu HM. (2010) FERONIA receptor-like kinase regulates RHO GTPase signaling of root hair development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 17821–17826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbak AR, Tax FE. (2011) CLAVATA signaling pathway receptors of Arabidopsis regulate cell proliferation in fruit organ formation as well as in meristems. Genetics 189: 177–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Lithy ME, Clerkx EJM, Ruys GJ, Koornneef M, Vreugdenhil D. (2004) Quantitative trait locus analysis of growth-related traits in a new Arabidopsis recombinant inbred population. Plant Physiol 135: 444–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Lithy ME, Reymond M, Stich B, Koornneef M, Vreugdenhil D. (2010) Relation among plant growth, carbohydrates and flowering time in the Arabidopsis Landsberg erecta × Kondara recombinant inbred line population. Plant Cell Environ 33: 1369–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Restrepo JM, Huck N, Kessler S, Gagliardini V, Gheyselinck J, Yang WC, Grossniklaus U. (2007) The FERONIA receptor-like kinase mediates male-female interactions during pollen tube reception. Science 317: 656–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J, Vieten A, Sauer M, Weijers D, Schwarz H, Hamann T, Offringa R, Jürgens G. (2003) Efflux-dependent auxin gradients establish the apical-basal axis of Arabidopsis. Nature 426: 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gälweiler L, Guan C, Müller A, Wisman E, Mendgen K, Yephremov A, Palme K. (1998) Regulation of polar auxin transport by AtPIN1 in Arabidopsis vascular tissue. Science 282: 2226–2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulini A, Wang J, Jackson D. (2004) Control of phyllotaxy by the cytokinin-inducible response regulator homologue ABPHYL1. Nature 430: 1031–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godiard L, Sauviac L, Torii KU, Grenon O, Mangin B, Grimsley NH, Marco Y. (2003) ERECTA, an LRR receptor-like kinase protein controlling development pleiotropically affects resistance to bacterial wilt. Plant J 36: 353–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SP, Chickarmane VS, Ohno C, Meyerowitz EM. (2009) Multiple feedback loops through cytokinin signaling control stem cell number within the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 16529–16534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudesblat GE, Schneider-Pizoń J, Betti C, Mayerhofer J, Vanhoutte I, van Dongen W, Boeren S, Zhiponova M, de Vries S, Jonak C, et al. (2012) SPEECHLESS integrates brassinosteroid and stomata signalling pathways. Nat Cell Biol 14: 548–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenot B, Bayer E, Kierzkowski D, Smith RS, Mandel T, Žádníková P, Benková E, Kuhlemeier C. (2012) Pin1-independent leaf initiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 159: 1501–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha CM, Jun JH, Fletcher JC. (2010) Shoot apical meristem form and function. Curr Top Dev Biol 91: 103–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada S, Onouchi H, Tanaka H, Kudo M, Liu YG, Shibata D, MacHida C, Machida Y. (2000) Mutations in the WUSCHEL gene of Arabidopsis thaliana result in the development of shoots without juvenile leaves. Plant J 24: 91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Kajita R, Torii KU, Bergmann DC, Kakimoto T. (2007) The secretory peptide gene EPF1 enforces the stomatal one-cell-spacing rule. Genes Dev 21: 1720–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Yokoo T, Kajita R, Onishi T, Yahata S, Peterson KM, Torii KU, Kakimoto T. (2009) Epidermal cell density is autoregulated via a secretory peptide, EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR 2 in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 1019–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler MG, Ohno C, Das P, Sieber P, Reddy GV, Long JA, Meyerowitz EM. (2005) Patterns of auxin transport and gene expression during primordium development revealed by live imaging of the Arabidopsis inflorescence meristem. Curr Biol 15: 1899–1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejátko J, Blilou I, Brewer PB, Friml J, Scheres B, Benková E. (2006) In situ hybridization technique for mRNA detection in whole mount Arabidopsis samples. Nat Protoc 1: 1939–1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hord CLH, Sun YJ, Pillitteri LJ, Torii KU, Wang H, Zhang S, Ma H. (2008) Regulation of Arabidopsis early anther development by the mitogen-activated protein kinases, MPK3 and MPK6, and the ERECTA and related receptor-like kinases. Mol Plant 1: 645–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt L, Gray JE. (2009) The signaling peptide EPF2 controls asymmetric cell divisions during stomatal development. Curr Biol 19: 864–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PJ, Hangarter RP, Estelle M. (1998) Auxin transport is required for hypocotyl elongation in light-grown but not dark-grown Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 116: 455–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson H, Heisler MG, Shapiro BE, Meyerowitz EM, Mjolsness E. (2006) An auxin-driven polarized transport model for phyllotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 1633–1638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karve R, Liu W, Willet SG, Torii KU, Shpak ED. (2011) The presence of multiple introns is essential for ERECTA expression in Arabidopsis. RNA 17: 1907–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW, Michniewicz M, Bergmann DC, Wang ZY. (2012) Brassinosteroid regulates stomatal development by GSK3-mediated inhibition of a MAPK pathway. Nature 482: 419–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Kajita R, Miyazaki A, Hokoyama M, Nakamura-Miura T, Mizuno S, Masuda Y, Irie K, Tanaka Y, Takada S, et al. (2010) Stomatal density is controlled by a mesophyll-derived signaling molecule. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D, Karve R, Willet A, Chen MK, Oden J, Shpak ED. (2012) Regulation of plasmodesmatal permeability and stomatal patterning by the glycosyltransferase-like protein KOBITO1. Plant Physiol 159: 156–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer EM. (2008) Computer models of auxin transport: a review and commentary. J Exp Bot 59: 45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurakawa T, Ueda N, Maekawa M, Kobayashi K, Kojima M, Nagato Y, Sakakibara H, Kyozuka J. (2007) Direct control of shoot meristem activity by a cytokinin-activating enzyme. Nature 445: 652–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak SH, Shen R, Schiefelbein J. (2005) Positional signaling mediated by a receptor-like kinase in Arabidopsis. Science 307: 1111–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Johnston R, Yang Y, Gallavotti A, Kojima M, Travençolo BA, Costa LdaF, Sakakibara H, Jackson D. (2009) Studies of aberrant phyllotaxy1 mutants of maize indicate complex interactions between auxin and cytokinin signaling in the shoot apical meristem. Plant Physiol 150: 205–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Zhong SH, Cui XF, Li J, He ZH. (2012) Characterization of temperature-sensitive mutants reveals a role for receptor-like kinase SCRAMBLED/STRUBBELIG in coordinating cell proliferation and differentiation during Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant J 72: 707–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann D, Stacey N, Breuninger H, Jikumaru Y, Müller D, Sicard A, Leyser O, Yamaguchi S, Lenhard M. (2010) SLOW MOTION is required for within-plant auxin homeostasis and normal timing of lateral organ initiation at the shoot meristem in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22: 335–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J, Barton MK. (2000) Initiation of axillary and floral meristems in Arabidopsis. Dev Biol 218: 341–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukowitz W, Roeder A, Parmenter D, Somerville C. (2004) A MAPKK kinase gene regulates extra-embryonic cell fate in Arabidopsis. Cell 116: 109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhavý P, Bielach A, Abas L, Abuzeineh A, Duclercq J, Tanaka H, Pařezová M, Petrášek J, Friml J, Kleine-Vehn J, et al. (2011) Cytokinin modulates endocytic trafficking of PIN1 auxin efflux carrier to control plant organogenesis. Dev Cell 21: 796–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Wang H, He Y, Liu Y, Walker JC, Torii KU, Zhang S. (2012) A MAPK cascade downstream of ERECTA receptor-like protein kinase regulates Arabidopsis inflorescence architecture by promoting localized cell proliferation. Plant Cell 24: 4948–4960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki K, Tarkowski P, Matsumoto-Kitano M, Kato T, Sato S, Tarkowska D, Tabata S, Sandberg G, Kakimoto T. (2006) Roles of Arabidopsis ATP/ADP isopentenyltransferases and tRNA isopentenyltransferases in cytokinin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 16598–16603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morillo SA, Tax FE. (2006) Functional analysis of receptor-like kinases in monocots and dicots. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9: 460–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A, Morin H, Traas J, Laufs P. (2007) Plants expressing a miR164-resistant CUC2 gene reveal the importance of post-meristematic maintenance of phyllotaxy in Arabidopsis. Development 134: 1045–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillitteri LJ, Bemis SM, Shpak ED, Torii KU. (2007) Haploinsufficiency after successive loss of signaling reveals a role for ERECTA-family genes in Arabidopsis ovule development. Development 134: 3099–3109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinon V, Prasad K, Grigg SP, Sanchez-Perez GF, Scheres B. (2013) Local auxin biosynthesis regulation by PLETHORA transcription factors controls phyllotaxis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 1107–1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragni L, Nieminen K, Pacheco-Villalobos D, Sibout R, Schwechheimer C, Hardtke CS. (2011) Mobile gibberellin directly stimulates Arabidopsis hypocotyl xylem expansion. Plant Cell 23: 1322–1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt D, Pesce ER, Stieger P, Mandel T, Baltensperger K, Bennett M, Traas J, Friml J, Kuhlemeier C. (2003) Regulation of phyllotaxis by polar auxin transport. Nature 426: 255–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpella E, Helariutta Y. (2010) Vascular pattern formation in plants. Curr Top Dev Biol 91: 221–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpella E, Marcos D, Friml J, Berleth T. (2006) Control of leaf vascular patterning by polar auxin transport. Genes Dev 20: 1015–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz M, Berleth T, Mattsson J. (2008) Multiple MONOPTEROS-dependent pathways are involved in leaf initiation. Plant Physiol 148: 870–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions A, Yanofsky MF, Weigel D. (2000) Cell-cell signaling and movement by the floral transcription factors LEAFY and APETALA1. Science 289: 779–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpak ED, Berthiaume CT, Hill EJ, Torii KU. (2004) Synergistic interaction of three ERECTA-family receptor-like kinases controls Arabidopsis organ growth and flower development by promoting cell proliferation. Development 131: 1491–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpak ED, Lakeman MB, Torii KU. (2003) Dominant-negative receptor uncovers redundancy in the Arabidopsis ERECTA Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase signaling pathway that regulates organ shape. Plant Cell 15: 1095–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpak ED, McAbee JM, Pillitteri LJ, Torii KU. (2005) Stomatal patterning and differentiation by synergistic interactions of receptor kinases. Science 309: 290–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RS, Guyomarc’h S, Mandel T, Reinhardt D, Kuhlemeier C, Prusinkiewicz P. (2006) A plausible model of phyllotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 1301–1306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova AN, Robertson-Hoyt J, Yun J, Benavente LM, Xie DY, Dolezal K, Schlereth A, Jürgens G, Alonso JM. (2008) TAA1-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell 133: 177–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova AN, Yun J, Robles LM, Novak O, He W, Guo H, Ljung K, Alonso JM. (2011) The Arabidopsis YUCCA1 flavin monooxygenase functions in the indole-3-pyruvic acid branch of auxin biosynthesis. Plant Cell 23: 3961–3973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugano SS, Shimada T, Imai Y, Okawa K, Tamai A, Mori M, Hara-Nishimura I. (2010) Stomagen positively regulates stomatal density in Arabidopsis. Nature 463: 241–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szemenyei H, Hannon M, Long JA. (2008) TOPLESS mediates auxin-dependent transcriptional repression during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Science 319: 1384–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Ferrer JL, Ljung K, Pojer F, Hong F, Long JA, Li L, Moreno JE, Bowman ME, Ivans LJ, et al. (2008) Rapid synthesis of auxin via a new tryptophan-dependent pathway is required for shade avoidance in plants. Cell 133: 164–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii KU, Mitsukawa N, Oosumi T, Matsuura Y, Yokoyama R, Whittier RF, Komeda Y. (1996) The Arabidopsis ERECTA gene encodes a putative receptor protein kinase with extracellular leucine-rich repeats. Plant Cell 8: 735–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N, Igari K, Bogenschutz NL, Torii KU, Tasaka M. (2011) Arabidopsis ERECTA-family receptor kinases mediate morphological alterations stimulated by activation of NB-LRR-type UNI proteins. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 804–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N, Lee JS, Horst RJ, Lai HH, Kajita R, Kakimoto T, Tasaka M, Torii KU. (2012a) Regulation of inflorescence architecture by intertissue layer ligand-receptor communication between endodermis and phloem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 6337–6342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N, Shimada M, Tasaka M. (2012b) Modulation of the balance between stem cell proliferation and consumption by ERECTA-family genes. Plant Signal Behav 7: 1506–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N, Shimada M, Tasaka M. (2013) ERECTA-family receptor kinases regulate stem cell homeostasis via buffering its cytokinin responsiveness in the shoot apical meristem. Plant Cell Physiol 54: 343–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zanten M, Snoek LB, Proveniers MCG, Peeters AJM. (2009) The many functions of ERECTA. Trends Plant Sci 14: 214–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernoux T, Brunoud G, Farcot E, Morin V, Van den Daele H, Legrand J, Oliva M, Das P, Larrieu A, Wells D, et al. (2011) The auxin signalling network translates dynamic input into robust patterning at the shoot apex. Mol Syst Biol 7: 508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernoux T, Kronenberger J, Grandjean O, Laufs P, Traas J. (2000) PIN-FORMED 1 regulates cell fate at the periphery of the shoot apical meristem. Development 127: 5157–5165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villagarcia H, Morin AC, Shpak ED, Khodakovskaya MV. (2012) Modification of tomato growth by expression of truncated ERECTA protein from Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot 63: 6493–6504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Ngwenyama N, Liu Y, Walker JC, Zhang S. (2007) Stomatal development and patterning are regulated by environmentally responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Went FW, Thimann KV (1937) Phytohormones. Macmillan, New York [Google Scholar]

- Werner T, Motyka V, Strnad M, Schmülling T. (2001) Regulation of plant growth by cytokinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10487–10492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward C, Bemis SM, Hill EJ, Sawa S, Koshiba T, Torii KU. (2005) Interaction of auxin and ERECTA in elaborating Arabidopsis inflorescence architecture revealed by the activation tagging of a new member of the YUCCA family putative flavin monooxygenases. Plant Physiol 139: 192–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Xu Y, Dong A, Sun Y, Pi L, Xu Y, Huang H. (2003) Novel as1 and as2 defects in leaf adaxial-abaxial polarity reveal the requirement for ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 and 2 and ERECTA functions in specifying leaf adaxial identity. Development 130: 4097–4107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama R, Takahashi T, Kato A, Torii KU, Komeda Y. (1998) The Arabidopsis ERECTA gene is expressed in the shoot apical meristem and organ primordia. Plant J 15: 301–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]