Abstract

Microbial (non-viral) keratitis is a serious vision-threatening condition. The management of microbial keratitis in children is particularly complicated by the children’s inability to cooperate during examinations and the lack of information prior to presentation. Predisposing factors vary according to geographical location and age. Corneal trauma is the leading cause for microbial keratitis in children, followed by systemic and ocular disease. Etiologic agents are most frequently Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria commonly found in contact lens-related microbial keratitis. Mycotic keratitis is a major risk factor in tropical weather conditions, particularly when associated with agricultural trauma. Early diagnosis, intensive drug treatment, and timely planned surgical intervention may effectively improve the outcome of pediatric microbial keratitis.

Keywords: Pediatric microbial keratitis, Children, Predisposing factor, Microbiology

Introduction

Corneal infection is a major cause of ocular morbidity and blindness worldwide, both in developed and developing countries.1 In developing countries, it is estimated that 1.5–8 million of corneal ulcers occur each year.2,3,5 Srinivasan et al.3 reported that ulceration of the cornea in South India “is a blinding disease of epidemic proportions.” Children presenting with microbial keratitis are at risk of developing irreversible ocular deficits, such as those resulting from amblyopia.2,15 Therefore, the diagnosis and treatment of microbial keratitis in children is of utmost importance. However, studies pertaining to microbial keratitis in children are scarce. Nonetheless, it is known that the microbial etiology and predisposing factors vary with geographic location and age.4–8 In addition to the lack of knowledge, management of microbial keratitis in children is hampered by the children’s inability to provide complete medical history and to cooperate during examination and treatment. Delay in management may cause severe visual impairment.

This review outlines the demographics, predisposing factors, laboratory and clinical findings, treatment, and outcome of microbial keratitis in children.

Incidence of microbial keratitis

Despite the improvements in treatment options, infectious microbial keratitis remains a significant cause of blindness worldwide.4 The incidence of microbial keratitis is higher in developing countries than in developed countries.5–7 Maurin et al.58 found that the incidence of corneal related blindness in children in tropical countries is 20 times higher than that in children from developed countries. In a study supervised by the World Health Organization (WHO) South-East Asia Regional Office in New Delhi, it has been estimated that 6 million cases of corneal ulcer occur every year in South-East Asia.5 The incidence of microbial keratitis ranges from 113 per 100,000 in India5 to as high as 799 per 100,000 in Nepal.6 On the other hand, the incidence of microbial keratitis in the United States was estimated to be 2–11 per 100,000.7

Microbial keratitis occurs more frequently in adults than in children. In agreement, in an epidemiological study of microbial keratitis in Southern California, only 11% of the cases involved children.8

Predisposing factors

Trauma

The most common predisposing factor for microbial keratitis in children is trauma.8–14,42 Corneal trauma disrupts the protective mechanism of the corneal epithelium, thereby facilitating bacterial adhesion and accelerating subsequent microbial penetration and replication.15,16 Different studies showed a decrease of corneal ulcers following traumas in adults59,60 which is a far more common predisposing factor in rural areas where it accounts for up to 77.5% of cases.61 Children are less cautious than adults, and they do not understand the inherent dangers associated with hazardous objects during their activities of daily life.52 Objects of trauma include plant, metal, or plastic pieces, firecrackers, and pencils. The history of trauma in childhood microbial keratitis was reported in 26% to 58.8%.8,9,13

Contact lens

Contact lens wear is a common predisposing factor in many developed countries.9,10 In fact, it has been considered the leading cause of microbial keratitis in Taiwan.15 This can be explained by the relatively high prevalence of refractive errors and the popularity of contact lens use in these areas. In particular, overnight orthokeratology (OK) was reported to be associated with infectious keratitis in myopic teenagers. Watt and Swarbrick56 have provided an analysis of the first 50 cases of microbial keratitis in overnight OK. Their findings showed that 60% of the affected OK patients were 15 years old or younger. Of interest, 30% of these OK-related cases were caused by Acanthamoeba, as opposed to only 5% of infections reported in regular contact lens wearers. However, contact lens-related microbial keratitis cases are usually associated with Pseudomonas micro-organisms. At all ages, Pseudomonas-mediated keratitis accounts for the largest mean diameter of corneal ulcers, highest number of outpatient visits, and poorest visual acuity outcome.55 Hence, potential visual complications should be considered when prescribing overnight lenses.15

Systemic and ocular diseases

Systemic infections and malignancies are the main causes in patients with severe systemic illness, especially in children below the age of 4.8–10 Systemic diseases and malnutrition reduce the wound healing process that may be an important reason for an increased risk for childhood microbial Keratitis.62 A wide range of systemic diseases, including hypoxic encephalopathy, pulmonary stenosis, malnutrition, multiple congenital abnormalities, and severe prematurity, was found to be associated with microbial keratitis in children.8–11,13 Health-impaired infants should receive additional medical attention to prevent microbial keratitis, to which they are more susceptible.15 The relationship between the health status and microbial keratitis in children was supported by two studies analyzing the risk factors for microbial keratitis in Indian children, which highlighted the association of protein-energy malnutrition, immunization profile, and low socioeconomic background with the development of microbial keratitis.12,16

Ocular conditions such as exposure keratopathy (Fig. 2), trichiasis, and dry eye are major contributors to microbial keratitis.2–4 Table 1 summarizes the risk factors reported in different studies.

Figure 2.

Bilateral cryptophalmous with exposure keratopathy and microbial keratitis in left eye.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of reported case series of childhood microbial keratitis.

| Source | Location | Risk factors (%) | Rate of Surgery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ormerod et al. 8 | Southern California | Trauma; ocular disease | 28 |

| Cruz et al. 9 | Florida | Trauma (44); prior corneal surgery (24); systemic disease (14); contact lens wear (12) | 14 |

| Clinch et al. 10 | New Orleans, LA and Philadelphia, PA | Trauma (34); systemic disease (27); contact lens wear (24) | 21 |

| Kunimoto et al. 11 | India | Trauma (21); ocular disease (18); systemic disease (16); contact lens wear (0) | 16 |

| Vajpayee et al. 12 | India | Trauma (38); systemic disease (24); ocular disease (12); contact lens wear (0) | 6 |

| Singh et al. 14 | India | Trauma (69); unknown (29.8); contact lens wear (1) | 2 |

| Hsiao et al. 15 | Taiwan | Contact lens wear (40.7); Trauma (21); Ocular disease (14.8); Systemic disease (11.1) | 14.8 |

| Song et al. 13 | China | Trauma (58.8); ocular disease (10); previous corneal refractive surgery (5) | 74 |

Clinical features of microbial keratitis

Microbial keratitis presents a wide range of clinical signs and symptoms. They include moderate to severe pain of rapid onset, severe redness of the conjunctiva, hazy vision, photophobia, discharge, and swollen lids. Signs usually include corneal infiltrate (either central or paracentral), epithelial defects over the infiltrate, inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber with or without hypopyon, folds in Descemet’s membrane, and sometimes endothelial inflammatory plaques. The wide spectrum of clinical manifestations can result in the incorrect selection of antimicrobial agents and a prolonged period of resolution.28,46

Pathogenesis of microbial keratitis

To establish a corneal infection, micro-organisms have to overcome the natural barriers present at the ocular surface. The defense mechanisms include an intact epithelial layer at the corneal surface and a tear film with antibacterial properties. Physical trauma usually precedes invasion of micro-organisms. Many bacteria display several adhesins on fimbriated and nonfimbriated structures that may aid in their adherence to the host corneal cells. After the successful invasion of the corneal surface, bacteria can proliferate and penetrate into the corneal stroma.47 The host response is crucial for protecting the cornea, but, at the same time, it can produce some of the pathology that is associated with infectious keratitis. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) are found at the inflammatory site soon after the infection. Their migration is associated with corneal damage and ultimately scarring or perforation in severe cases.48 Degranulation of PMNs releases host enzymes and toxins that kill the invading bacteria and degrade the corneal stroma. Influx of PMNs is mediated, on the one hand, by chemokines and cytokines that are produced by the host soon after the infection49 and, on the other, by chemotactic bacterial peptides and endotoxins.50 The host inflammatory response is regulated by a different network of chemokines and cytokines that are released soon after infection to prevent further stromal damage and to stimulate wound healing.51

Microbiology analysis

Normal flora of the conjunctiva

The normal ocular flora of newborns is acquired mainly from the birth canal during normal delivery. It includes Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Corynebacterium, Peptostreptococcus, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and propionibacterium species.37 Streptococci mainly dominate the normal conjunctival flora of older children, and corynebacteria are more abundant toward adulthood.

Microbiology spectrum

Bacteria

Non-viral microbial keratitis in children is caused mainly by bacteria and, to a lesser extent, by fungi or parasites. Amoebae such as Acanthamoeba sp. are more related to contact lens-associated keratitis but are rarely reported in childhood microbial keratitis.17,18

The rate of culture-positive specimens varies between reports and is in the range of 48–87%. This wide range can be explained by different laboratory facilities and previous use of topical antibiotics prior to scraping.

Of the reported culture-positive groups, Staphylococcus species were among the most common isolated organisms. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae are the predominant Gram-positive bacteria and Pseudomonas aeuroginosa is the main Gram-negative bacterium associated with microbial keratitis in children.10–14

Coagulase-negative staphylococci, including S. epidermidis, are the most common bacteria comprising the normal conjunctival flora.19,20 These bacteria have been reported to be associated with high incidence of microbial keratitis in children.10–14

Like in adults, the microbial keratitis spectrum in children varies according to the geographical location. Studies from South California, Florida, and Taiwan reported a high rate of isolates of P. aeuroginosa.8,11,15 Other studies conducted in New Orleans, LA, Philadelphia, PA, and India have reported a markedly lower prevalence of P. aeruginosa.10,12 In the United States and Taiwan, P. aeruginosa isolates were associated with high number of contact lens-related corneal ulcers. Poor contact lens hygiene in contact lens-related keratitis was noted in two studies.10,15 Table 2 highlights the incidence of different micro-organisms isolated in studies on childhood microbial keratitis.

Table 2.

Incidence of micro-organisms isolated from adults and children with microbial keratitis.

| Location | No. of cases | Age (y) | % Culture positive (No.) | % With >1 species isolated (No.) | % No. of cases with fungal sp. | % Of culture positive (No.) |

Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Staphylococcus aureus | Pseudomonas aeroginosa | Streptococcus pneumoniae | α-Hemolytic streptococci | |||||||

| US | |||||||||||

| Los Angeles | 47 | Children (0–16) | 87 (41) | 27 (11) | 4 (2) | 17 (7) | 17 (7) | 24 (10) | 20 (8) | 17 (7) | Ormerod et al. 8 |

| Philadelphia/New Orleans | 29 | Children (0–16) | 76 (22) | 7 (21) | 14 (4) | 23 (5) | 5 (1) | 9 (2) | 9 (2) | NR | Clinch et al. 10 |

| Miami | 51 | Children (0–16) | 86 (44) | 12 (6) | 16 (8) | 2 (1) | 21 (9) | 34 (15) | 7 (3) | 4.5 (2) | Cruz et al. 9 |

| South Florida | 663 | All ages (0–95) | 56 (371) | 4 (15) | 20 (133) | 3 (19) | 8 (51) | 11 (74) | 3 (18) | 2 (13) | Liesgang and Forster 36 |

| Los Angeles | 227 | All ages (0–95) | 82 (186) | 33 (62) | 11 (20) | NR | 22 (41) | 19 (35) | 15 (27) | 9 (17) | Ormerod et al. 38 |

| India | |||||||||||

| Hyderabad | 113 | Children (0–16) | 57 (64) | 18 (18) | 10 (11) | 23 (15) | 20 (13) | 9 (6) | 19 (2) | NR | Kunimoto et al. 11 |

| New Delhi | 3528 | All ages | 55 (1931) | NR | 24 (857) | NR | 5 (98) | 16 (312) | 1 (13) | NR | Stapathy and Vishalakashi 23 |

| India | 50 | Children (0–16) | 35 (70) | NR | 5 (14) | 21 (60) | 3 (8) | 7 (14) | 0 | 0 | Vajpayee et al. 12 |

| India | 310 | Children (0–16) | 97(31.2) | 4(4.1) | 37 (38.1) | 16 (15.8) | 7(6.9) | 18 (17.8) | 6 (5.9) | NR | Singh et al. 14 |

| Sweden | |||||||||||

| Göteborg | 48 | All ages (5–89) | 63 (30) | 7 (2) | 0 | 23 (7) | 30 (9) | 10 (9) | 13 (4) | NR | |

| Taiwan | 81 | Children (0–16) | 47 (58) | 2 (4.2) | 3 (6.4) | 1 (2.1) | 9 (19.1) | 21 (44.7) | 5 (10.6) | 1 (2.1) | Hsiao et al. 15 |

| China | 80 | Children (0–16) | 39 (48.8) | 1(2.6) | 19 (48.7) | 14 (35.9) | 1(2.6) | 1 (2.6) | NR | NR | Song et al. 13 |

NR = not reported.

Fungi

Fungal microbial keratitis in children has been reported in several studies.9,10,12–14 A significant incidence of filamentous fungi in childhood microbial keratitis in Southern cities of the United States, China, and India has been reported. This can be attributed to the relation between fungal infection and tropical climate. Keratomycosis tends to increase in humid environment. Regardless of the geographical location, the major predisposing factor for fungal keratitis is trauma in the agricultural environment.13,14 The agricultural environment is rich in bacteria and fungi. Upon trauma caused by plants or vegetable materials, micro-organisms penetrate the cornea leading to keratitis.37

Several studies from different parts of the world show variable incidence of fungal keratitis. Cruz et al.9 reported an incidence rate of 18% of fungal microbial keratitis in children in the United States. Song et al.13 reported that 48.7% of the cases of childhood microbial keratitis in China is caused by fungal micro-organisms. A large (213 children) retrospective analysis of mycotic keratitis in India showed that Aspergillus, followed by Fusarium species, were the major causative fungi in childhood keratomycosis.21

Diagnosis of microbial keratitis in children

Clinical examination

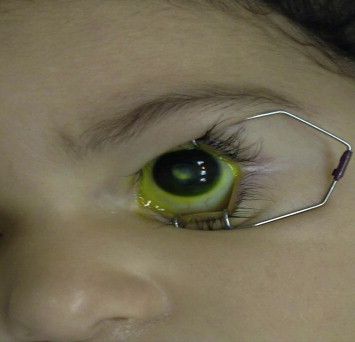

A complete medical history and thorough eye examination focusing on characteristic clinical features are essential for an etiological diagnosis.22,23 Despite the fact that it is not always easy to obtain a detailed history and to perform a thorough clinical exam on younger children, these measures should not be compromised. Full eye examination and scraping of the infected cornea are required under sedation or general anesthesia when dealing with children who are suspected to have microbial keratitis (Fig. 1). However, Thomas et al.26 in a study investigating a possible correlation between clinical examination and the specific infecting agent in microbial keratitis, concluded that the clinical features of microbial keratitis may vary significantly and that no clinical feature can be considered absolutely pathognomonic of a particular type of infectious agent. Similar results were observed in another study.25 Both studies concluded that clinical examination alone cannot be taken as a basis for deciding the therapeutic regimen that should be followed for a specific microbial organism.24,25

Figure 1.

Corneal scar after microbial keratitis.

Microbiology workup

Corneal scrapings in children require sedation or general anesthesia, especially if they are less than 2 years of age.12 Corneal scraping smears are inoculated in blood, chocolate, Sabouraud agar, Lowenstein–Jensen agar, and thioglycolate broth. Cultures for Acanthamoeba are performed if indicated by clinical appearance or history. In general, corneal scrapings and microbiological examination yield positive cultures in only 52–65% of cases.38–41 Microscopic slides are used for stained smears with Gram, Giemsa, and acid-fast staining/acridine orange/calcofluor white (if fungi or Acanthamoeba are suspected).41

Treatment

Antibacterial

Current therapeutic strategies to treating microbial keratitis aim at eradicating the microbial agent and moderating the host immune response with corticosteroids to reduce the scarring while minimizing potential visual impairments. Topical application of the antimicrobial agents will lead to high concentration of the drug at the infection site. Treatment of microbial keratitis needs aggressive and frequent administration of the antimicrobial agents, which can be difficult when treating children. At present, the standard treatment consists of either fortified antibiotics – in the form of concentrated aminoglycoside and cefazolin (e.g., tobramycin 1.3% and cefazolin 5%) – or monotherapy with second-generation fluoroquinolone eye drops.26–29 In a 2003 review published in the British Journal of Ophthalmology, about 75% of the corneal ulcers were treated with fluoroquinolone monotherapy.57 The fourth-generation ophthalmic fluoroquinolones include moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin are being used for the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Both antibiotics have better in vitro activity against Gram-positive bacteria than ciprofloxacin or ofloxacin. Moxifloxacin penetrates better into ocular tissues than gatifloxacin against gram-negative bacteria is similar to that of older fluoroquinolones.63,64

These findings suggest that, moxifloxacin or gatifloxacin may ba a preferred alternative to ciprofloxacin as the first-line monotherapy in bacterial keratitis. A more recent study33 did not show any difference in the efficacy of monotherapy with fourth-generation fluoroquinolones in the treatment of bacterial corneal ulcers when compared with combination therapy of fortified antibiotics, which could reduce the frequency of application of antimicrobial drugs in uncooperative children.

In crying uncooperative children, regular topical administration of the topical antibiotics is not feasible, which has led some investigators to advocate repeated subconjuctival injection under sedation and papoose restraint.8,31

Antifungal

Unlike antibiotics for bacteria, the spectrum of antifungal medications is limited and more often associated with poor corneal penetration and less antifungal activity against infecting fungi, which make mycotic keratitis more prone to corneal perforation and ocular complications, such as endophthalmitis, in comparison to bacterial keratitis.30 Nonetheless, topical natamycin (5%), fluconazole (0.5%), and amphotericin B (0.25%) are known to be effective antifungal drugs in treating childhood microbial keratitis.10,11,13

Corticosteroids

The action of corticosteroids is known to slow down the host inflammatory response and may hinder the eradication of invading micro-organisms.53 The role of corticosteroid remains controversial; however, when they are used, close follow-up and strict guidelines are mandatory to ensure the best outcome for these patients. In general, corticosteroids are recommended for less severe cases of corneal ulceration that are small in size and peripheral in location.38 They should not be used until specific antimicrobial therapy has controlled microbial proliferation, and clear clinical improvement is evident.54

Outcome

Most ulcers, including those occurring in children below the age of 3 years, are successfully treated with topical therapy alone.9–11

The rate of surgical intervention (in the form of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty and conjunctival flaps, therapeutic lamellar keratoplasty, and debridement, alone or in combination with amniotic membrane transplantation) is less than 20% in treated children with microbial keratitis in most of the reports8–15 (Table 1).

One study from China13 reported high incidence of surgical intervention (74%). This figure is probably attributed to the fact that majority of the patients lived in rural areas in China and were exposed to agricultural activities, leading to a high fungal infection rate (48.7%).

Severe protein-energy malnutrition and bilateral keratitis cases have been associated with a higher rate of surgical intervention. In general, patients without protein-energy malnutrition were 36% less likely to have a poor outcome.16 On the other hand, the visual prognosis for fungal keratitis in children has been associated with poor outcome.32–35

Parmar et al. compared microbial keratitis in three different groups: a pediatric group, an elderly group, and a control group between 17 and 64 years of age. They found that microbial keratitis in children was more likely to be associated with bacterial infection, non severe ulcers, and more likely to resolve with medical therapy alone when compared with microbial keratitis in adults.36 A study published by Hsiao et al.15 concluded that poor vision outcome was associated with polymicrobial infection, fungal infection, systemic disease, and ocular disease.

Summary

Pediatric microbial keratitis is an uncommon but potentially serious condition. The causative micro-organisms of (non-viral) microbial keratitis in children are predominantly bacteria and to a lesser extent, fungi. Of the bacteria pathogens, Staphylococcus sp., S. pneumonia, and P. aeruginosa are the most common. The risk factors for microbial keratitis in children include trauma, severe systemic and ocular disease, and contact lens wear. Treatment for pediatric microbial keratitis usually starts with application of fortified topical antimicrobial drugs, followed by anti-inflammatory agents. Children suffering from microbial keratitis are at risk of amblyopia.15 Thus, early diagnosis and treatment is necessary to minimize any vision-threatening complications.

References

- 1.Whitcher J.P., Srinivasan M., Upadhyay M.P. Corneal blindness: a global perspective. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:214–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitcher J.P., Srinivasan M. Cornel ulceration in the developing world- a silent epidemic. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;8:622–631. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.8.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srinivasan M., Gonzales C.A., George C. Epidemiology and etiological diagnosis of corneal ulceration in Madurai, South India. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:965–971. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.11.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Resnikoff S., Pascolini D., Elya Ale D. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organization. 2004;82:844–855. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzales C.A., Srinivasan M., Whitcher J.P. Incidence of corneal ulceration in Madurai District, South India. Ophthal Epiddemol. 1996;3:159–166. doi: 10.3109/09286589609080122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upadhyay M.P., Karmacharya P.C., Koirala S. The Bhaktapur eye study: ocular trauma and antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of corneal ulceration in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:388–392. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.4.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erie J.C., Nevitt M.P., Hodge D.O. Incidence of corneal ulceration in a defined population from 1950–1988. Arh Ophthalmol. 1991;11:92–99. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ormerod L.D., Murphree A.L., Gomez D.S., Schanzlin D.J., Smith R.E. Microbial Keratitis in children. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:449–455. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz O.A., Sabir S.M., Capo H., Alfonso E.C. Microbial keratitis in childhood. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:192–196. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinch T.E., Plamon F.E., Robinson M.J., Cohen E.J., Barron B.A., Laibson P.R. Microbial keratitis in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kunimoto D.Y., Sharma S., Reddy MK; Mirobial keratitis in children. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:252–257. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(98)92899-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vajpayee R.B., Ray M., Panda A. Risk factors for pediatric presumed microbial keratitis: a case control study. Cornea. 1999;18:565–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song X, Xu L, Sun S, Zhao J, Xie L. Pediatric microbial keratitis: a tertiary hospital study. Eur J Ophthalmol 2011; pii: 5F077621-4EB2-45C9-8D08-0EF9C819AEBB. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2011.8338. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Singh G., Palanisamy M., Madhavan B. Multivariate analysis of childhood microbial keratitis in South India. Ann Acad Med. 2006;35:186–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsiao C.H., Yeung L., Ma D.H. Pediatric microbial keratitis in Taiwanese children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(5):603–609. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jhanji V., Naithani P., Lamoureux E., Agrawal T. Immunization and nutritional profile of cases with atraumatic microbial keratitis in preschool age group. American J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazlett L.D., Kreindler F.B., Berk R.S. Aging alters the phagocytic capability of inflammatory cells induced in the cornea. Curr Eye Res. 1990;20:10–18. doi: 10.3109/02713689008995199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klotz S.A., Au Y.K., Misra R.P. A partial thickness epithelial defect increases the adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30:1069–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishibashi Y. Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmologica. 1997;211(Suppl 1):39–44. doi: 10.1159/000310885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Resnikoff S., Paniagua-Crespo E., Mjjikam J.M. First cases of keratitis caused by free-living amoebas of the genus Acanthamoeba diagnosed in Mali. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1991;84:1016–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perkins R.E., Kundsin R.B., Pratt M.V. Bacteriology of normal and infected conjunctiva. J Clin Microbiol. 1975;1:147–149. doi: 10.1128/jcm.1.2.147-149.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stapleton F., Willcox M.D.P., Fleming C.M. Changes in the ocular biota with time in extended and daily wear disposable contact lens use. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4501–4505. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4501-4505.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stapathy G., Vishalakashi P. Ulcerative keratitis:microbial profile and sensitivity pattern: a five year study. Ann Ophthalmol. 1995;27:301–306. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones D.B. Decision-making in the management of microbial keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1981;88:814–820. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(81)34943-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benson W.H., Lanier J.D. Current diagnosis and treatment of corneal ulcers. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1998;9:45–49. doi: 10.1097/00055735-199808000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas P.A., Leck A.K., Myatt M. Characteristic clinical features as an aid to the diagnosis of suppurative keratitis caused by filamentous fungi. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1554–1558. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.076315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahlgren M.A., Lingappan A., Wilhemus K.R. The clinical diagnosis of microbial keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:940–944. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panda A., Sharma N., Das G. Mycotic keratitis in children: epidemiologic and microbiologic evaluation. Cornea. 1997;16:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isenberg S.J., Apt L., Yoshimori R. Source of the counjuctival bacterial flora at birth and implications for ophthalmia neonatorum prophylaxis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:458–462. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90883-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilhelmus K.R., Hyndiuk R.A., Caldwell D.R. Ciprofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic ointment in the treatment of bacterial keratitis. The Ciprofloxacin Ointment Bacterial Keratitis Study Research Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:1210–1218. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090090062020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parks D.J., Abrams D.A., Sarfarazi F.A. Comparison of topical ciprofloxacin to conventional antibiotic therapy in treatment of ulcerative keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;115:471–477. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74449-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’ Brien T.P., Maguire M.G., Fink N.E. Efficacy of ofloxacin vs cefazolin and tobramycin in the therapy for bacterial keratitis. Report from the Bacterial Keratitis Study Research Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1257–1265. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100100045026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah V.M., Tandon R., Dip N.B., Satapathy G. Randomized clinical study for comparative evaluation of fourth-generation fluoroquinolones with the combination of fortified antibiotics in the treatment of bacterial corneal ulcers. Cornea. 2010;29:751–757. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181ca2ba3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong T.Y., Fong K.S., Tan D.T. Clinical and microbial spectrum of fungal keratitis in Singapore: a 5-year retrospective study. Int Ophthalmol. 1997;21:127–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1026462631716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baum J., Barza M. Topical versus subconjctival treatment of corneal ulcers. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:162. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34583-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liesgang T.J., Forster R.K. Spectrum of microbial keratitis in South Florida. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90:38–47. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asbell P., Stenon S. Ulcerative keratitis: survey of 30 years laboratory experience. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:77–80. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030030079005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ormerod L.D., Hertzmark E., Gomez D.S. Epidemiology of microbial keratitis in southern California: a multivariate analysis. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:1322–1333. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)80019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fong C.F., Tseng C.H., Hu F.R., Wang I.J., Chen W.L., Hou Y.C. Clinical characteristics of microbial keratitis in a university hospital in Taiwan. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parmar P., Salman A., Kalvathy C.M., Kaliamurthy J., Thomas P.A., Jesudasan C.A. Microbial keratitis at extreme age. Cornea. 2006;25:153–158. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000167881.78513.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulshreshtha O.P., Bhargava S., Dube M.K. Keratomycosis: a report of 23 cases. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1973;103:636–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gopinathan U., Sharma S., Garg P. Review of epidemiological features, microbiological diagnosis and treatment outcome of microbial keratitis: experience over a decade. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:273–279. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.53051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Behrens-Baumann W. Topical antimycotics in Ophthalmology. Ophthalmologica. 1997;211:33–38. doi: 10.1159/000310884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen L., Hazlett L.D. Perlecan in the basement membrane of corneal epithelium serves as a site for P. aeruginosa binding. Curr Eye Res. 2000;20:260–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsumoto K., Shams N.B., Hanninen L.A. Proteolytic activation of corneal matrix metalloproteinase by Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase. Curr Eye Res. 1992;11:1105–1109. doi: 10.3109/02713689209015082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tumpey T.M., Cheng H., Cook D.N. Absence of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha prevents the development of blinding herpes stromal keratitis. J Virol. 1998;67:347–356. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3705-3710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thakur A., Willcox M.D.P. Chemotactic activity of tears and bacteria isolated during adverse responses. Exp Eye Res. 1998;66:129–137. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kernacki K.A., Barrett R.P., Hobden J.A. Macrophage inflammatory protein 2 is a mediator of polymorphonuclear neutrophil influx in ocular bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:1037–1045. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hill J.R., Crawford B.D., Lee H., Tawansy K.A. Evaluation of open globe injuries of children in the last 12 years. Retina. 2006;26:S66–S68. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000224668.21622.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen E.J. Management of small corneal infiltrates in contact lens wearers. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:276–277. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stern G.A., Buttros M. Use of corticosteroids in combination with antimicrobial drugs in the treatment of infectious corneal disease. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:847–853. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng K.H., Leung S.L., Hoekman H.W., Beekhuis W.H., Mulder P.G., Geerards A.J., Kijlstra A. Incidence of contact-lens-associated microbial keratitis and its related morbidity. Lancet. Jul 17 1999;354(9174):181–185. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watt K., Swarbrick H.A. Microbial keratitis in overnight orthokeratology: review of the first 50 cases. Eye Contact lens. Sept 2005;31(5):201–208. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000179705.23313.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeng B.H., McLeod S.D. Microbial keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:805–806. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maurin J.F., Renard J.P., Ahmedou O. Corneal blindness in tropical areas. Med Trop (Mars) 1995;55:445–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gudmundsson O.G., Ormerod D.L. Factors influencing predilection and outcome in bacterial Keratitis. Cornea. 1989;8:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohen E.J., Fulton J.C. Trends in contact lens-associated corneal ulcers. Cornea. 1996;15:566–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vajpayee R.B., Dada T. Study of the first contact management profile of cases of infectious keratitis: a hospital-based study. Cornea. 2000;19:52–56. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200001000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Emery P.W., Sanderson P. The effects of dietary restriction on protein synthesis and wound healing after surgery in the rat. Clin Sci. 1995;89(4):383–388. doi: 10.1042/cs0890383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schlech B.A., Alfonso E. Overview of the potency of moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution 0.5% (VIGAMOX) Surv Ophthalmol. Nov 2005;50(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.05.002. S7-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parmar P., Salman A. Comparison of topical gatifloxacin 0.3% and ciprofloxacin 0.3% for the treatment of bacterial Keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. Feb 2006;141(2):282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]