Abstract

Objective

To develop and evaluate a short self-report tool to predict low pharmacy refill adherence by using pharmacy refill data in older patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of survey and administrative data data from the Cohort Study of Medication Adherence among Older Adults (CoSMO).

Participants

Three hundred ninety-four adults with uncontrolled blood pressure; mean ± SD age was 76.6 ± 5.6 years, 33.0% were black, 66.0% were women, and 23.4% had a low medication possession ratio (MPR).

Measurements and Main Results

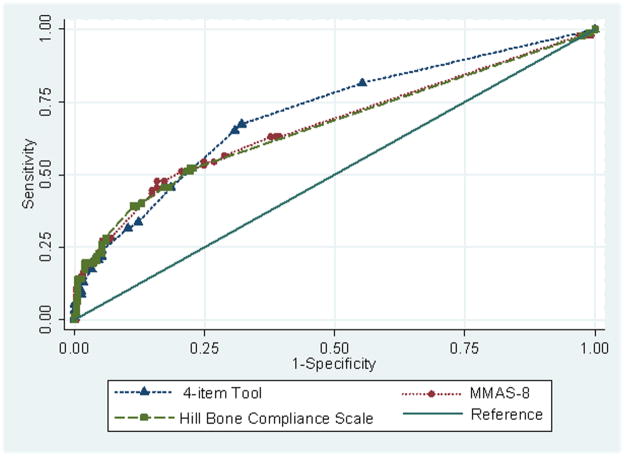

We considered 164 self-reported candidate items for development of a prediction rule for low (< 0.8) vs. high (≥ 0.8) MPR from pharmacy refill data. Risk prediction models were evaluated by using best subsets analyses, and the final model was chosen based on clinical relevance and model parsimony. Bootstrap simulations assessed internal validity. The performance of the final 4-item model was compared to the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) and the 9-item Hill-Bone Compliance Scale. The 4-item self-report tool for predicting pharmacy refill adherence showed moderate discrimination (C statistic 0.704, 95% CI 0.683–0.714) and good model fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 = 1.238, p=0.743). Sensitivity and specificity were 67.4% and 67.8%, respectively. The C statistics for MMAS-8 and the Hill-Bone Compliance Scale were lower at 0.665 (95% CI 0.632–0.683) and 0.660 (95% CI 0.622–0.674), respectively.

Conclusion

A 4-item self-report tool moderately discriminated low from high pharmacy refill adherers, and its test performance was comparable to existing 8- and 9-item adherence scales. Parsimonious self-report tools predicting low pharmacy refill in patients with uncontrolled blood pressure could facilitate hypertension management in the elderly.

Keywords: hypertension, medication adherence, pharmacy refill, uncontrolled blood pressure, risk prediction

Hypertension persists as a major public health and clinical challenge; data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2008 indicate that 33.5% of US adults (76,400,000 individuals) have hypertension 1–3. Uncontrolled blood pressure is a major risk factor for coronary heart disease, stroke, renal failure, all-cause mortality, and shortened life expectancy 4. Effective medical therapies exist; yet, only 69% of US adults treated for hypertension have controlled blood pressure 2. Given that medication adherence rates are estimated at 50% for long-term medications 5, low adherence to prescribed medications has been implicated as one of the key contributors to uncontrolled blood pressure 6–8. In a meta-analysis, the odds ratio (OR) for hypertension control among patients adherent versus those not adherent to antihypertensive medications was 3.44 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.60–7.37) 6.

The commonly used self-report antihypertensive medication adherence tools were developed to identify barriers to adherence and predict blood pressure control in predominantly middle-aged adult populations receiving outpatient care for hypertension 9–11. Yet, their performance in different populations has varied 12. Given the high prevalence of hypertension and the challenge of low adherence in the elderly, combined with limited resources in clinical practice, there is a need to accurately identify low adherers among older adults with uncontrolled blood pressure so they can be triaged for intervention. Use of antihypertensive medication refills is an objective adherence measure associated with blood pressure control and good clinical outcomes 13–15; however, refill data are not accessible in most clinical practices. Thus, there is a need for a simple tool that can predict the occurrence of low pharmacy refills in high-risk older patients with uncontrolled hypertension to facilitate hypertensive management in clinical settings.

Results from prior research suggest that a risk prediction model based on healthcare administrative data alone cannot accurately predict whether patients are adherent to antihypertensive medications by using pharmacy refill data16. It is possible that administrative data models have been unsuccessful in predicting adherence because they fail to include major barriers that are typically collected through patient self-report (e.g. medication-taking self-efficacy and quality of life). We previously described a conceptual model outlining multiple risk factors and barriers associated with poor adherence and uncontrolled hypertension 17. However, few datasets are available that include comprehensive assessment of risk factors and barriers in addition to pharmacy refill data.

We hypothesized that more extensive assessment of risk factors and barriers to medication adherence collected by using validated patient self-report tools may yield a risk prediction tool for pharmacy refills with better discrimination than that reported by using administrative databases alone. In addition, we hypothesized that the tool would perform as well as the longer existing self-report adherence tools. To test these hypotheses, we developed a self-report tool for predicting low adherence in refilling antihypertensive medications from patients enrolled in the Cohort Study of Medication Adherence among Older Adults (CoSMO)8 who had uncontrolled blood pressure and compared its performance to the existing self-report Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) and the Hill-Bone Compliance Scale.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of survey and administrative data from participants enrolled in the CoSMO study, a prospective cohort study assessing barriers to and determinants of medication adherence in older adults.8 The CoSMO study design, recruitment flowchart, response rates, and baseline characteristics of participants have been previously described 8. The CoSMO study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the privacy board of the managed care organization. In brief, community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older with established and treated essential hypertension were randomly selected by using a random number generator from the roster of a large managed care organization in southeastern Louisiana; blacks and men were oversampled to ensure adequate enrollment in the study population. Between August 2006 and September 2007, 2194 individuals completed a baseline survey. Participants were resurveyed one and two years later. The recapture rate was 93.6% for the follow-up surveys. All data for study measures included in this analysis (i.e., candidate items for risk prediction models and pharmacy fill) came from the first follow-up survey (which included a broader data collection for risk factors) and administrative database downloads. In an effort to identify patients with established hypertension who should be assessed for adherence problems in the outpatient setting, the study sample was limited to 394 participants with uncontrolled blood pressure, using an established definition of systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg 1. The prevalence of uncontrolled blood pressure among treated adults with hypertension in the CoSMO population was 33.7% 8, a rate that is comparable to the US estimate of 31% for uncontrolled hypertension among treated adults 2. Seated systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements taken at the clinic visit occurring prior to the survey date were abstracted from medical records by trained research staff by using standardized forms. Blood pressure levels were averaged when more than one measurement was taken at the clinic visit (mean number of measurements per visit was 1.25 [range 1–4]). Of note, the sample for the current analysis was comparable to the CoSMO population on key characteristics. There were no significant differences in age, race, education, or duration of hypertension (p>0.10 for all comparisons) between those included versus those not included in the analytic sample. Participants included in the analytic sample of uncontrolled blood pressure versus those not included were more likely to be women (66.0% versus 57.3%, p<0.01).

Pharmacy Refill Outcome Measure: Medication Possession Ratio

Data for the primary outcome measure, pharmacy refills, came from the data warehouse system of the managed care organization in which all CoSMO patients were enrolled. Pharmacy refill data included a listing of all prescriptions filled, the date filled, generic and brand names of the drugs, and number of pills dispensed at each pharmacy fill. From these data, the medication possession ratio (MPR) for antihypertensive medications was calculated as the sum of the days’ supply obtained between the first pharmacy fill and the last fill (the supply obtained in the last fill was excluded), divided by the total number of days over the one year interval. For participants filling more than one class of antihypertensive medication, the MPR was calculated for each class, and the data were averaged across all classes to assign a single MPR for each participant. If a participant filled a combination medication with 2 or more classes, the fill data were used to calculate each class-specific MPR and then averaged across all classes as described above 18;19. In accordance with previous studies, a cut point of less than 0.8 was used to define low MPR 20.

Candidate Items for Explanatory Variables

We considered 164 candidate items for development of a prediction rule for low MPR. All candidate items were selected based on an established conceptual model 17 and came from a telephone survey that included validated questionnaires administered by trained interviewers 8. The questionnaires included in this tool development were publically available without copyright restrictions. An outline of the constructs and data sources used to select candidate items is presented in Table 1. Survey questions included assessment of sociodemographics (age, sex, race, education, and marital status) and patient risk factors including clinical characteristics, smoking status, alcohol use, and use of the health care system. Questions assessing presence of depressive symptoms, social support, quality of life, and perceived stress came from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale 21, the RAND Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey 22, the RAND Medical Outcomes Study 36-item tool 23;24, and the Perceived Stress Scale 25, respectively. Questions assessing patients’ medication adherence self-efficacy were assessed by using the Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale 26. Questions assessing the use of lifestyle modifications (weight control, salt reduction, fruit and vegetable consumption) to lower blood pressure came from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 27. Questions assessing complementary and alternative therapies (including general use, health food and herbal supplements, and relaxation techniques) to help control blood pressure came from a modified Complementary and Alternative Therapies Survey 28;29. Finally, items assessing patients’ medication-taking behavior were measured by using the 9-item medication-taking subscale from the Hill-Bone Compliance Scale9.

Table 1.

Constructs and Data Sources for Developing an Adherence Risk Prediction Tool

| Construct | Source | Description of Candidate Items |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics and other risk factors | CoSMO survey 8 | 13 questions assessing sociodemographics (age, sex, race, education, and marital status) and patient risk factors including clinical characteristics, smoking status, alcohol use, and use of the health care system. |

| Social Support | RAND Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey 22 | 19 questions assessing various functional dimensions of social support including emotional/informational, tangible, affectionate, and positive interaction. |

| Functional Status and Quality of Life | RAND Medical Outcomes Study 36-item (MOS SF-36) 23 | 36 questions assessing eight health concepts: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, role limitations due to mental health problems, bodily pain, general health perception, vitality, social |

| Lifestyle Modifications | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 27. | 4 questions assessing specific actions patients take to lower their blood pressure such as weight control, salt reduction, and fruit and vegetable consumption. |

| Patients’ use of complementary and alternative therapies | Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapies Survey 29 | 4 multipart questions assessing the use of complementary or alternative therapies including general use, health food and herbal supplements, and relaxation techniques to help control blood pressure. |

| Depressive symptoms | National Institute of Mental Health Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) 21 | 20 questions assessing depressive affect, somatic symptoms, positive affect, and interpersonal relations. |

| Perceived stress | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) 25 | 4 questions assessing how often patients have felt psychological stress in the last month. |

| Medication adherence self-efficacy | Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale 26 | 12 questions for patients to rate how sure they are that they can take their blood pressure medication all of the time in certain situations. |

| Self-reported adherence behavior | Hill-Bone Compliance Scale 9 | 9 questions assessing patients’ medication-taking behavior for high blood pressure therapy. |

Existing Medication Adherence Scales

Data from two previously published medication adherence scales were collected as part of the first follow-up survey in the CoSMO study: the MMAS-8 and the Hill-Bone Compliance Scale. The 8-item MMAS-8 was designed to facilitate the identification of barriers to and behaviors associated with adherence to long-term medications and has been determined to be significantly associated with blood pressure control (p<0.05) in cross-sectional studies 10. The MMAS-8 score can range from 0–8, with higher scores reflecting better adherence. The 9-item Hill-Bone Compliance scale was designed as a simple tool for clinicians to evaluate patients’ self-reported adherence. Each item has a 4-point Likert response format, and total score can range from 9–36, with lower scores reflecting better adherence 9;30.

Statistical Analysis

The distribution of responses for each candidate item was examined, and variables were either coded as linear terms or indicator variables. Bivariate associations between low MPR and the 164 individual items from these survey tools were examined, and 61 candidate items associated with an MPR < 0.8 at the p ≤ 0.25 level were considered in the development of candidate multivariable logistic regression models (Appendix 1). We used a best subset logistic regression approach in developing the self-report tool to avoid having an excessive number of predictors in any model. 31–33. To avoid overfitting our model, we restricted the subset sizes to 9 or fewer independent variables (i.e., <1 per every 10 participants with low MPR) in an a priori fashion. Among models with similar fit statistics and concordance measures, a final model was chosen based on clinical relevance of the items and model parsimony. Using previously established methods 34, we developed a risk prediction scoring system from the intercept and beta coefficients of the 4-item logistic regression model. To determine the points associated with each of the categories of the risk factors, each beta coefficient was divided by a constant value, which was the log of the lowest OR from the 4-item model (OR 1.23). One point was assigned for response options reflecting less than perfect medication-taking behavior or limitations in health, yielding a possible range of 0 (highest adherence) to 4 (lowest adherence) points. Other scoring systems using alternate constant values were considered; however, because the simplified (0–4-point range) scoring system was comparable to alternate systems, we chose to present the simplified scoring results for ease of use 34. We then calculated the sensitivity and specificity of the 4-item tool for predicting pharmacy refill adherence via MPR by using multiple cut points. Optimal sensitivity and specificity were attained with the cut point of <1 (i.e. high adherence) vs ≥1 (i.e., low adherence). The concordance statistic (C statistic) was used to assess the model’s discrimination of low versus not low adherers. Ranging from 0.5 to 1.0, higher values of the C statistic correspond to better discrimination of low adherers from not low adherers. The 95% confidence interval of the C statistic was calculated from bootstrap simulations (using 10,000 replications) including a deflation factor for performance optimism to assess internal validation of the predictive model 35. Goodness of fit of the model was assessed with the Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 statistic.

Comparison with Existing Adherence Tools

The prediction of low pharmacy refills using MPR was also determined by using the MMAS-8 and the Hill-Bone Compliance Scale. The C statistics of these models were compared to those of the 4-item tool predicting pharmacy refill adherence we developed in the overall population and stratified by age, sex, race, and comorbidity. We assessed whether the discriminatory properties of the 4-item tool were comparable to existing medication adherence tools for prediction of low pharmacy refill using MPR by using area under the curve (AUC) tests 36. Finally, by using previously published cut points (8 for “high adherence” vs < 8 for “not high adherence” in the MMAS-810 and 9 for “perfect adherence” vs > 9 for “imperfect adherence in the Hill-Bone Compliance Scale37), we calculated the sensitivity and specificity of each existing self-reported adherence tool and compared the results with the 4-item tool predicting pharmacy refill adherence by using MPR. All analyses were conducted by using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The mean ± SD age of the 394 participants included in the sample was 76.6 ± 5.6 years, 33.0% were black, 66.0% were women, 48.0% were married, 64.5% had hypertension duration ≥10 years, and 45.7% filled three or more classes of antihypertensive medications in the prior year (Table 2). An MPR of <0.8 was present in 23.4% of participants. Black patients and patients with higher comorbidity scores had a statistically significantly higher prevalence of MPR <0.8 compared to white patients and those with lower comorbidity scores (Table 2). Additionally, each candidate item selected for the final model (i.e., medication-taking behavior, medication-taking self-efficacy, and physical function) was significantly associated with MPR <0.8.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Participants with Uncontrolled Blood Pressure Overall, and % with Low and Not Low Pharmacy Refill Adherence

| Characteristic | Overall (n=394)a | % with Low Pharmacy Refill Adherence Using MPR (n=92) | % with Not Low Pharmacy Refill Adherence Using MPR (n=302) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (yrs) | |||

| < 75 | 41.2 | 24.1 | 75.9 |

| ≥ 75 | 58.8 | 22.8 | 77.2 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 66.0 | 25.0 | 75.0 |

| Male | 34.0 | 20.1 | 79.9 |

| Race-ethnicity | |||

| Black | 33.0 | 32.3 | 67.7* |

| Nonblack | 67.0 | 18.9 | 81.1 |

| Education | |||

| < High school education | 23.1 | 28.6 | 71.4 |

| ≥ High school education | 76.9 | 21.8 | 78.2 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 48.0 | 22.2 | 77.8 |

| Not married | 52.0 | 24.4 | 75.6 |

| Hypertension duration at baseline (yrs) | |||

| <10 | 35.5 | 20.7 | 79.3 |

| ≥ 10 | 64.5 | 24.8 | 75.2 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | |||

| < 2 | 43.2 | 17.1 | 82.9 |

| ≥ 2 | 56.9 | 28.1 | 71.9* |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)b | |||

| < 30 | 63.9 | 23.3 | 76.7 |

| ≥ 30 | 36.2 | 24.1 | 75.9 |

| No. of antihypertensive drug classes | |||

| < 3 | 54.3 | 20.6 | 79.4 |

| ≥ 3 | 45.7 | 26.7 | 73.3 |

|

| |||

| Select Candidate Itemsc | |||

|

| |||

| How often do you forget to take your high BP medicine? 9 | |||

| None | 79.4 | 17.9 | 82.1** |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 20.6 | 44.4 | 55.6 |

| How often do you miss taking your high BP pills when you feel better? 9 | |||

| None | 95.4 | 21.3 | 78.7** |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 4.6 | 66.7 | 33.3 |

| How sure are you that you can take your blood pressure medication all of the time when you worry about taking them for the rest of your life? 26 | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 92.9 | 21.6 | 78.4** |

| Somewhat/not at all sure | 7.1 | 46.4 | 53.6 |

| Does your health now limit you in moderate activities, such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf? 23 | |||

| Not limit you at all | 51.0 | 18.9 | 81.1* |

| Limit you a little | 31.5 | 24.2 | 75.8 |

| Limit you a lot | 17.5 | 34.8 | 65.2 |

Data are percentages of participants. Low pharmacy refill adherence = medication possession ratio (MPR) <0.80; not low pharmacy refill adherence = MPR ≥0.80.

P<0.05,

P<0.01.

To be eligible for inclusion in the derivation sample, participants must have completed the first follow-up of the Cohort Study of Medication Adherence among Older Adults (CoSMO) survey and had uncontrolled blood pressure (mean systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90) in the year prior to the follow-up survey and had no missing data on all MMAS-8 and Hill-Bone Compliance Scale questions.

Due to missing data on 4 patients, 390 had data to calculate BMI

A full list of candidate items is included in Appendix 1.

The associations between each of the 61 candidate items and low MPR are shown in Appendix 1. The multivariable-adjusted odds ratios for low pharmacy refill adherence using MPR in the final predictive model are shown in Table 3. This final model includes 2 items assessing medication nonadherence from the Hill-Bone Compliance Scale,9 one item assessing concerns about medication-taking behavior from the Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale,26 and one item on functional status/quality of life from the RAND Medical Outcomes Study 36-item tool.23 The 2 items with the strongest association with low MPR are from the Hill-Bone Compliance Scale: missing taking medications when patient feels better (OR 5.06, 95% CI 1.71–15.03) and forgetting to take medications (OR 3.18, 95% CI 1.81–5.61). The other 2 items, health limiting moderate activities a lot (OR 2.81, 95% CI 1.47–5.35) and unsure about taking medications all of the time when patient is worried about taking them the rest of his or her life (OR 2.62, 95% CI 1.11–6.20) were also significantly associated with low MPR. The final model showed moderate discrimination and had good model fit (Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit χ2 = 1.238, p=0.743). In the overall population, the 4-item tool had a C statistic of 0.704 (95% CI 0.683–0.714) compared to 0.665 (95% CI 0.632–0.683) and 0.660 (95% CI 0.622–0.674) for the MMAS-8 and the Hill-Bone Scale, respectively.

Table 3.

Multivariable-Adjusted Odds Ratios for Low Pharmacy Refill Adherence in the Final Predictive Model for the 394 Participants

| Variable | No. (%) of Participants with Low Pharmacy Refill Adherence Using MPR | Adjusted Odds Ratioa (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you forget to take your high BP medicine? 9 | |||

| None (n=313) | 56 (17.9) | 1 (reference) | |

| Some, most, or all of the time (n=81) | 36 (44.4) | 3.18 (1.81–5.61) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| How often do you miss taking your high BP pills when you feel better? 9 | |||

| None (n=376) | 80 (21.3) | 1 (reference) | |

| Some, most, or all of the time (n=18) | 12 (66.7) | 5.06 (1.71–15.03) | 0.003 |

|

| |||

| How sure are you that you can take your blood pressure medication all of the time when you worry about taking them for the rest of your life? 26 | |||

| Very sure or not applicable (n=366) | 79 (21.6) | 1 (reference) | |

| Somewhat or not at all sure (n=28) | 13 (46.4) | 2.62 (1.11–6.20) | 0.027 |

|

| |||

| Does your health now limit you in moderate activities, such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf? 23 | |||

| Not limit you at all (n=201) | 38 (18.9) | 1 (reference) | |

| Limit you a little (n=124) | 30 (24.2) | 1.23 (0.69–2.21) | 0.277 |

| Limit you a lot (n=69) | 24 (34.8) | 2.81 (1.47–5.35) | 0.002 |

Low pharmacy refill adherence = medication possession ratio (MPR) <0.80.

Each odds ratio is adjusted for all other variables shown in this table.

The 4-item tool showed comparable discrimination when compared with existing longer tools (p=0.110 for the difference in AUC of the Hill-Bone Compliance Scale vs the 4-item tool, and p=0.201 for the difference in AUC of the MMAS-8 vs the 4 item tool; Figure 1). In the stratified analyses, the C statistics were similar by sex, but differences were identified for age, comorbidity, and race. The difference in C statistic by race was notable for the 4-item tool; the C statistic was 0.760 (95% CI 0.687–0.832) for nonblacks and 0.663 (95% CI 0.558–0.768) for blacks. The differences in the C statistics by race for the MMAS-8 and the Hill-Bone were not as large (Table 4), although the C statistics were less than 0.7 for each of these scales for both blacks and nonblacks.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve comparison of the 4-item tool, the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8), and the 9-item Hill-Bone Compliance Scale.

Table 4.

C statistics for the 4-Item Tool, the 8-Item MMAS-8, and the 9-Item Hill-Bone Compliance Scale

| C Statistic (95% confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Characteristic | 4-Item Tool Predicting Pharmacy Refill Adherence | 8-Item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) | 9-Item Hill-Bone Compliance Scale |

| Age (yrs) | |||

| ≥ 75 (n=232) | 0.684 (0.593–0.775) | 0.663 (0.577–0.750) | 0.710 (0.633–0.786) |

| <75 (n=162) | 0.742 (0.649–0.834) | 0.706 (0.608–0.803) | 0.640 (0.548–0.733) |

| Sex | |||

| Male (n=134) | 0.716 (0.606–0.827) | 0.642 (0.514–0.770) | 0.623 (0.505–0.741) |

| Female (n=260) | 0.719 (0.642–0.795) | 0.698 (0.621–0.776) | 0.690 (0.618–0.761) |

| Race-ethnicity | |||

| Black (n=130) | 0.663 (0.558–0.768) | 0.673 (0.590–0.774) | 0.684 (0.590–0.778) |

| Nonblack (n=264) | 0.760 (0.687–0.832) | 0.652 (0.562–0.742) | 0.655 (0.573–0.737) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | |||

| ≥ 2 (n=224) | 0.698 (0.622–0.774) | 0.660 (0.579–0.741) | 0.655 (0.577–0.733) |

| < 2 (n=170) | 0.742 (0.637–0.846) | 0.746 (0.649–0.843) | 0.685 (0.579–0.792) |

Using a cut point of ≥1 to identify low adherers (versus <1 for high adherers), the sensitivity and specificity of the 4-item tool was 67.4% and 67.8%, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity were also calculated for the MMAS-8 (sensitivity and specificity of 65.2% and 57.6% for a score < 8 [not high adherence] versus a score of 8 [high adherence], respectively) and the Hill-Bone Compliance Scale (sensitivity and specificity of 54.3% and 74.8% for a score <9 [imperfect adherence] versus a score of 9 [perfect adherence], respectively).

Discussion

Low adherence to antihypertensive medications is a barrier to controlled blood pressure in elderly patients. Pharmacy refill is an objective and important measure of adherence. However, pharmacy refill data are not routinely available in most outpatient medical practices. Using comprehensive data collected from the CoSMO study, we developed and internally validated a simple tool to identify individuals with uncontrolled blood pressure who have a high likelihood of low pharmacy refill adherence. The responses to the items composing the tool (i.e., missing taking medications when feeling better, forgetting to take medications, unsure about taking medications all of the time when worried about taking them for the rest of their life, and health limiting moderate activities a lot) may provide important insights into known barriers to medication-taking in clinical settings. The 4-item tool had moderate discrimination, indicated by a C statistic of 0.704 in the CoSMO study. The performance of the 4-item tool in terms of C statistics, sensitivity, and specificity were comparable with the existing 8-item MMAS and the 9-item Hill-Bone Scale. As hypothesized, the 4-item tool based on self-reported items performed better (C statistic 0.704, multivariable odds ratios >2.5 for each item) than a previously published tool that used sociodemographic and clinical characteristics from administrative datasets to predict refill adherence in patients with hypertension (C statistic 0.606, multivariable odds ratios ≤ 1.7 for each item)16.

Despite the performance of the 4-item tool, there is still opportunity for improvement in predicting pharmacy refill adherence using self-reported items. The 4-item model performed comparably to the MMAS-8 and Hill-Bone scales in the overall population. Some differences were observed among the scales when stratified by age, race, and comorbidity. Of particular interest is the analysis stratified by race where the difference in the C statistic (0.760 in nonblacks and 0.663 in blacks) revealed suboptimal performance in blacks compared to nonblacks. Although the C statistics stratified by race for the MMAS-8 and Hill-Bone revealed slightly better performance in blacks than nonblacks, they were still <0.7 in both groups for each scale. It is important to note that the sample size for blacks in the current study was small and the finding of lower performance in blacks could be a chance finding. Thus, further evaluation of the 4-item scale developed in the current study, especially in blacks, is warranted. We used a structured approach and data from a comprehensive database to produce a parsimonious and clinically relevant model of 4 items. Each of these items was identified from constructs (medication-taking behavior, self-efficacy, and physical functioning) that have been previously reported to be associated with low pharmacy refill adherence 8;18;24;38. The present study extends prior reports by grouping a small number of items into a screening tool that could be used to identify elderly patients with low pharmacy refill adherence among those with uncontrolled hypertension. This may be particularly useful in clinical practice when attempting to distinguish patients who have resistant hypertension from those who are poor adherers to prescribed antihypertensive medications. Tools such as these could also be used to identify elderly patients for follow-up with their physician, other healthcare provider, health coach, or pharmacist for interventions to improve medication adherence. Improved adherence may result in better disease control, improved outcomes, and lower healthcare costs in these high-risk adults 39–41. Given that the 4-item tool presented here had moderate discrimination and sensitivity and specificity metrics, future studies should venture to identify screening tools with improved test characteristics.

Limitations and Strengths

The items for the 4-item tool predicting pharmacy refill adherence were based on self-report tools that are available in the public domain. It is possible that inclusion of other variables, such as social determinants, financial barriers, access to care, and specific adverse effects of medications, or use of copyrighted tools may result in a model with different and perhaps better performance metrics. This study considered a large number of potential predictors selected on the basis of established associations with medication adherence and a previously published conceptual model among 394 individuals with uncontrolled hypertension of whom 92 had poor adherence. We used a best subset logistic regression approach in developing the self-report tool to avoid having an excessive number of predictors and over fitting the models. However, given the limited sample size, this 4-item tool should be validated in other larger studies. Of note, there is no gold standard for measuring medication adherence, and each method has limitations 42;43. Although pharmacy fill data are becoming increasingly available, less than 30% of US adults receive care in settings where pharmacy fill data are readily available 44. The patients included with uncontrolled hypertension were identified by using blood pressure data abstracted from medical records and not measured using a study protocol. The current study was limited to English-speaking adults aged 65 years and older with health insurance in one region of the US, and generalizability may be limited. However, almost all US citizens ≥ 65 years of age have health insurance and pharmacy benefits through Medicare 45. The 4-item tool has not yet been validated using an external dataset. Despite these limitations, strengths of this study include a diverse population of community-dwelling older adults with uncontrolled blood pressure, extensive collection of data regarding risk factors and barriers to medication adherence, availability of pharmacy refill data, and availability of 2 existing self-report scales (MMAS-8 and Hill- Bone Compliance Scale) for comparison with the 4-item tool. The restriction of our sample to older adults in a managed care setting minimizes the confounding effects of health insurance, access to medical care, and employment status in older adults.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Poor adherence to medications is a concern because of increasing evidence that it is prevalent and associated with adverse events and higher medical costs 46. In addition, the use of performance measures that reward quality based on the attainment of blood pressure control reinforces the importance of continuous medication adherence 47. Nevertheless, medication adherence is not routinely assessed during outpatient visits, 48 possibly because providers may not think of low adherence as the reason for uncontrolled blood pressure or they are uncertain about how to feasibly measure adherence in clinical practice. Our study results indicate that self-reported adherence tools may be able to identify older adults with uncontrolled blood pressure who have low pharmacy fill rates. Although existing 8- and 9-item scales appear to be useful in research settings and take 5–10 minutes to complete, these may be too long for use in busy clinical practices. The simple 4-item tool developed in the current study may be more practical and acceptable to clinicians seeking to identify high-risk older adults for adherence interventions. This tool provides similar information to existing tools, reflects pharmacy refill behavior, and takes less than 5 minutes to complete. Further research is warranted to explore the added value and cost implications of collecting self-report adherence in clinical practice.

Conclusion

Low adherence to antihypertensive medications is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease, mortality, and high healthcare costs. Despite the importance of medication adherence to effective management of hypertension, it is not routinely assessed in clinical practice. The 4-item self-report tool developed in the current study has moderate discrimination in detecting low pharmacy refill adherence in elderly patients and performs similarly to existing 8- and 9-item tools. Opportunities exist to improve screening tools for antihypertensive medication adherence assessment. The availability of short screening tools with strong test characteristics can increase awareness and detection of and counseling for low antihypertensive medication adherence in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Permission to use the MMAS-8 is required from Donald E. Morisky, Sc.D., UCLA School of Public Health, Los Angeles, California.

Funding Source: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (grant no. R01 AG022536; principal investigator: M. Krousel-Wood). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix 1. Association Between the 61 Candidate Items and Low Pharmacy Refill Adherence

| Candidate Item | Overall (n=394)a | % with Low Pharmacy Refill Adherence Using MPR | % with Not Low Pharmacy Refill Adherence Using MPR |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 9-item Hill-Bone Compliance Scale9 | |||

| How often do you… | |||

| …forget to take your high BP medicine? | |||

| None | 79.4 | 17.9 | 82.1** |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 20.6 | 44.4 | 55.6 |

| …decide not to take your high BP medicine? | |||

| None | 95.2 | 21.9 | 78.1** |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 4.8 | 52.6 | 47.4 |

| …run out of high BP pills? | |||

| None | 91.1 | 21.2 | 78.8** |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 8.9 | 45.7 | 54.3 |

| …skip your high BP medicine before you go to the doctor? | |||

| None | 91.9 | 20.4 | 79.6** |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 8.1 | 56.3 | 43.8 |

| …miss taking your high BP pills when you feel better? | |||

| None | 95.4 | 21.3 | 78.7** |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 4.6 | 66.7 | 33.3 |

| …miss taking your high BP pills when you feel sick? | |||

| None | 97.2 | 22.2 | 77.8** |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 2.8 | 63.6 | 36.4 |

| … miss taking your high blood pressure pills when you are careless? | |||

| None | 88.1 | 21.0 | 79.0** |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 11.9 | 40.4 | 59.6 |

| … miss scheduled appointments? | |||

| None | 85.3 | 21.1 | 78.9* |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 14.7 | 36.2 | 63.8 |

| … forget to get prescriptions filled? | |||

| None | 95.4 | 22.6 | 77.4 |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 4.6 | 38.9 | 61.1 |

| …eat fast food? | |||

| None | 31.0 | 17.2 | 82.8* |

| Some, most, or all of the time | 69.0 | 26.1 | 73.9 |

|

| |||

| Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale | |||

| How sure are you that you can take your blood pressure medication all of the time… | |||

| … when the time to take them is between your meals? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 94.4 | 22.6 | 77.4 |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 5.6 | 36.4 | 63.6 |

| … when you are busy at home? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 93.4 | 21.5 | 78.5** |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 6.6 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| … when you are at work? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 99.0 | 23.1 | 76.9 |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 1.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| …when you are afraid of becoming dependent on them? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 89.6 | 22.4 | 77.6 |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 10.4 | 31.7 | 68.3 |

| … if they sometimes make you feel dizzy? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 91.6 | 21.9 | 78.1* |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 8.4 | 39.4 | 60.6 |

| … when you feel well? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 94.2 | 21.6 | 78.4** |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 5.8 | 52.2 | 47.8 |

| …if they sometimes make you tired? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 92.9 | 21.3 | 78.7** |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 7.1 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| … when you take them more than once a day? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 95.2 | 21.9 | 78.1** |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 4.8 | 52.6 | 47.4 |

| … when you feel you do not need them? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 91.6 | 21.3 | 78.7** |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 8.4 | 45.5 | 54.6 |

| … when you do not have any symptoms? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 93.7 | 22.2 | 77.8* |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 6.3 | 40.0 | 60.0 |

| … when you have other medications to take? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 94.9 | 22.2 | 77.8* |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 5.1 | 45.0 | 55.0 |

| … when there is no one to remind you? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 92.6 | 21.6 | 78.4** |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 7.4 | 44.8 | 55.2 |

| … when you are afraid they may affect your sexual performance? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 92.9 | 21.6 | 78.4** |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 7.1 | 46.4 | 53.6 |

| … when they cause some side effects? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 88.6 | 22.4 | 77.7 |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 11.4 | 31.1 | 68.9 |

| … when you are traveling? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 95.4 | 22.3 | 77.7* |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 5.6 | 44.4 | 55.6 |

| … when you are with family? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 94.7 | 22.5 | 77.5 |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 5.3 | 38.1 | 61.9 |

| … when they make you urinate while away from home? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 88.6 | 22.1 | 77.9 |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 11.4 | 33.3 | 66.7 |

| … take your blood pressure medications for the rest of your life? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 92.9 | 21.6 | 78.4** |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 7.1 | 46.4 | 53.6 |

| How sure are you that you can… | |||

| … make taking your medications part of your routine? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 96.5 | 22.4 | 77.6* |

| Somewhat/not at all sure | 3.5 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| … fill your prescriptions whatever they cost? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 74.4 | 21.8 | 78.2 |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 25.6 | 27.7 | 72.3 |

| … always remember to take your blood pressure medications? | |||

| Very sure or not applicable | 89.3 | 22.2 | 77.8 |

| Somewhat or not at all sure | 10.7 | 33.3 | 66.7 |

|

| |||

| Smoking Status8 | |||

| Have you smoked 100 or more cigarettes in your life? | |||

| Yes | 51.9 | 19.3 | 80.8* |

| No | 48.1 | 27.7 | 72.3 |

|

| |||

| Medication Adherence and Cost | |||

| In the last year, have you ended up taking less high blood pressure medication than was prescribed for you because of the cost? | |||

| Yes | 3.3 | 46.2 | 53.9 |

| No | 96.7 | 22.4 | 77.6 |

|

| |||

| Depression Questionnaire21 | |||

| I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor | |||

| Rarely or none of the time | 84.5 | 22.9 | 77.1 |

| Some, a little, or most of the time | 6.4 | 40.0 | 60.0 |

| I felt that people disliked me | |||

| Rarely or none of the time | 93.6 | 22.4 | 77.6 |

| Some, a little, or most of the time | 6.4 | 40.0 | 60.0 |

| I felt that everything I did was an effort | |||

| Rarely or none of the time | 76.4 | 21.3 | 78.7 |

| Some, a little, or most of the time | 23.6 | 30.1 | 69.9 |

| I enjoyed life | |||

| Rarely or none of the time | 87.8 | 21.1 | 78.9* |

| Some, a little, or most of the time | 12.2 | 37.5 | 62.5 |

| I felt fearful | |||

| Rarely or none of the time | 86.7 | 23.2 | 76.8 |

| Some, a little, or most of the time | 13.3 | 23.1 | 72.9 |

| I felt lonely | |||

| Rarely or none of the time | 79.3 | 21.5 | 78.5* |

| Some, a little, or most of the time | 20.7 | 30.9 | 69.1 |

| I was happy | |||

| Rarely or none of the time | 80.5 | 22.7 | 77.3 |

| Some, a little, or most of the time | 19.5 | 26.0 | 74.0 |

|

| |||

| RAND Medical Outcomes Study 36-item tool 23 | |||

| During the past 4 weeks have you had any of the following problems with your work as a result of your physical health: | |||

| Have you accomplished less than you would like? | |||

| Yes | 47.6 | 26.7 | 73.3 |

| No | 52.4 | 20.4 | 79.6 |

| Have you cut down the amount of time you spent on work or other activities? | |||

| Yes | 32.8 | 29.5 | 70.5* |

| No | 67.2 | 20.4 | 79.6 |

| During the past 4 weeks have you had any of the following problems with your work as a result of any emotional problems (such as feeling anxious or depressed) … | |||

| Have you accomplished less than you would like? | |||

| Yes | 22.7 | 30.3 | 69.7 |

| No | 77.3 | 21.5 | 78.6 |

| Have you cut down the amount of time you spent on work or other activities? | |||

| Yes | 16.1 | 30.2 | 69.8 |

| No | 83.9 | 21.7 | 78.4 |

| Have you had difficulty performing the work or other activities (for example, it took extra effort)? | |||

| Yes | 47.4 | 26.9 | 73.1 |

| No | 52.6 | 20.0 | 80.0 |

| During the past 4 weeks, how much of the time has your physical health or emotion problems interfered with your social activities (like visiting with friends, relatives, etc.)? | |||

| All, most, or some of the time | 13.2 | 40.4 | 59.6* |

| A little of the time | 23.7 | 23.7 | 76.3 |

| None of the time | 63.1 | 19.8 | 80.2 |

| Does your health now limit you in moderate activities, such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf? | |||

| Not limit you at all | 51.2 | 18.9 | 81.1* |

| Limit you a little | 31.5 | 24.2 | 75.8 |

| Limit you a lot | 17.5 | 34.8 | 65.2 |

| Does your health now limit you in bathing or dressing yourself? | |||

| Not limit you at all | 86.8 | 21.4 | 78.7* |

| Limit you a little | 10.7 | 40.5 | 59.5 |

| Limit you a lot | 2.5 | 20.0 | 80.0 |

| Does your health now limit you in climbing one flight of stairs? | |||

| Not limit you at all | 55.0 | 18.2 | 81.8* |

| Limit you a little | 28.8 | 25.9 | 74.1 |

| Limit you a lot | 16.2 | 34.9 | 65.1 |

| Does your health now limit you in climbing several flights of stairs? | |||

| Not limit you at all | 27.6 | 15.9 | 84.1 |

| Limit you a little | 35.6 | 22.5 | 77.5 |

| Limit you a lot | 36.9 | 28.7 | 71.3 |

| Does your health now limit you in lifting or carrying groceries? | |||

| Not limit you at all | 56.5 | 18.0 | 82.0* |

| Limit you a little | 29.8 | 30.8 | 69.2 |

| Limit you a lot | 13.7 | 29.6 | 70.4 |

| Does your health now limit you in walking more than a mile? | |||

| Not limit you at all | 33.6 | 20.0 | 80.0 |

| Limit you a little | 27.1 | 19.1 | 80.9 |

| Limit you a lot | 39.5 | 29.6 | 70.4 |

| Does your health now limit you in walking one blocks? | |||

| Not limit you at all | 67.2 | 18.9 | 81.1* |

| Limit you a little | 21.9 | 33.7 | 66.3 |

| Limit you a lot | 10.9 | 30.2 | 69.8 |

| Does your health now limit you in walking several blocks? | |||

| Not limit you at all | 46.8 | 18.0 | 82.0 |

| Limit you a little | 25.1 | 24.5 | 75.5 |

| Limit you a lot | 28.1 | 30.9 | 69.1 |

| How much bodily pain have you had during the past 4 weeks? | |||

| None | 22.4 | 25.0 | 75.0 |

| Very mild | 20.9 | 17.1 | 82.9 |

| Mild | 23.2 | 20.9 | 79.1 |

| Moderate | 21.4 | 22.6 | 77.4 |

| Severe or very severe | 12.2 | 37.5 | 62.5 |

| In the past 4 weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work (including both work outside the home and housework)? | |||

| Not at all | 44.8 | 20.5 | 79.6 |

| A little bit | 28.2 | 23.4 | 76.6 |

| Moderately | 15.3 | 20.0 | 80.0 |

| Quite a bit or extremely | 11.7 | 39.1 | 60.9 |

| How much of the time during the past 4 weeks have you been a very nervous person? | |||

| A good bit, most, or all of the time | 4.1 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| Some of the time | 10.2 | 22.5 | 77.5 |

| A little of the time | 23.4 | 19.6 | 80.4 |

| None of the time | 62.3 | 22.9 | 77.1 |

| How much of the time during the past 4 weeks have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up? | |||

| Some, a good bit, most, or all of the time | 7.4 | 24.1 | 75.9 |

| A little of the time | 16.0 | 31.8 | 68.3 |

| None of the time | 76.7 | 21.5 | 78.5 |

| How much of the time during the past 4 weeks did you feel worn out? | |||

| A good bit, most, or all of the time | 15.7 | 30.0 | 70.0 |

| Some of the time | 31.7 | 26.4 | 73.6 |

| A little of the time | 24.6 | 16.5 | 83.5 |

| None of the time | 27.9 | 22.7 | 77.3 |

| How much of the time during the past 4 weeks did you feel tired? | |||

| A good bit, most, or all of the time | 20.7 | 28.4 | 71.6 |

| Some of the time | 35.2 | 23.2 | 76.8 |

| A little of the time | 30.9 | 22.3 | 77.7 |

| None of the time | 13.3 | 19.2 | 80.8 |

| How true is this statement for you: I seem to get sick a little easier than other people. | |||

| Definitely true | 2.8 | 36.4 | 63.6 |

| Mostly true | 7.4 | 27.6 | 72.4 |

| Don’t know | 10.9 | 34.9 | 65.1 |

| Mostly false | 37.2 | 20.6 | 79.5 |

| Definitely false | 41.7 | 21.3 | 78.7 |

Data are percentages of participants. Low pharmacy refill adherence = medication possession ratio (MPR) <0.80; not low pharmacy refill adherence = MPR ≥0.80.

P<0.05,

P<0.01.

To be eligible for inclusion in the derivation sample, participants must have completed the first follow-up of the Cohort Study of Medication Adherence among Older Adults (CoSMO) survey and had uncontrolled blood pressure (mean systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90) in the year prior to the follow-up survey and had no missing data on all MMAS-8 and Hill-Bone Compliance Scale questions.

Reference List

- 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynes RB, McDonald HP, Garg AX. Helping patients follow prescribed treatment: clinical applications. JAMA. 2002;288:2880–2883. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002;40:794–811. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kravitz RL, Melnikow J. Medical adherence research: time for a change in direction? Med Care. 2004;42:197–199. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000115957.44388.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Islam T, Morisky DE, Webber LS. Barriers to and determinants of medication adherence in hypertension management: perspective of the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:753–769. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MT, Hill MN, Bone LR, Levine DM. Development and testing of the Hill-Bone Compliance to High Blood Pressure Therapy Scale. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2000;15:90–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7117.2000.tb00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood MA, Ward H. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10:348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koschack J, Marx G, Schnakenberg J, Kochen MM, Himmel W. Comparison of two self-rating instruments for medication adherence assessment in hypertension revealed insufficient psychometric properties. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey JE, Wan JY, Tang J, Ghani MA, Cushman WC. Antihypertensive medication adherence, ambulatory visits, and risk of stroke and death. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:495–503. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1240-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho PM, Magid DJ, Shetterly SM, et al. Medication nonadherence is associated with a broad range of adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2008;155:772–779. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kettani FZ, Dragomir A, Cote R, et al. Impact of a better adherence to antihypertensive agents on cerebrovascular disease for primary prevention. Stroke. 2009;40:213–220. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.522193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steiner JF, Ho PM, Beaty BL, et al. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are not clinically useful predictors of refill adherence in patients with hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:451–457. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.841635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krousel-Wood M, Thomas S, Muntner P, Morisky D. Medication adherence: a key factor in achieving blood pressure control and good clinical outcomes in hypertensive patients. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:357–362. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000126978.03828.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krousel-Wood M, Islam T, Webber LS, Re RN, Morisky DE, Muntner P. New medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in seniors with hypertension. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizzo JA, Simons WR. Variations in compliance among hypertensive patients by drug class: Implications for health care costs. Clin Ther. 1997;19:1446–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sikka R, Xia F, Aubert RE. Estimating medication persistency using administrative claims data. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:449–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36-item health survey 1. 0. Health Econ. 1993;2:217–227. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holt EW, Muntner P, Joyce CJ, Webber L, Krousel-Wood MA. Health-related quality of life and antihypertensive medication adherence among older adults. Age Ageing. 2010;39:481–487. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogedegbe G, Mancuso CA, Allegrante JP, Charlson ME. Development and evaluation of a medication adherence self-efficacy scale in hypertensive African-American patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:520–529. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Study. Atlanta, GA: NCHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed February 1, 2011]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes2003-2004/BPQ_C.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Joyce CJ, et al. Adverse effects of complementary and alternative medicine on antihypertensive medication adherence: findings from the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lengacher CA, Bennett MP, Kipp KE, Berarducci A, Cox CE. Design and testing of the use of a complementary and alternative therapies survey in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:811–821. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.811-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krousel-Wood M, Muntner P, Jannu A, Desalvo K, Re RN. Reliability of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. Am J Med Sci. 2005;330:128–133. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Petrov BN, Csaki F, editors. Second international symposium on information theory. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado; 1973. pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hosmer DW, Jovanovic B, Lemeshow S. Best subsets logistic regression. Biometrics. 1989;45:1265–1270. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan LM, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RB., Sr Presentation of multivariate data for clinical use: The Framingham Study risk score functions. Stat Med. 2004;23:1631–1660. doi: 10.1002/sim.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE, Jr, Borsboom GJ, Eijkemans MJ, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JD. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:774–781. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krousel-Wood MA, Islam T, Muntner P, et al. Medication adherence in older clinic patients with hypertension after Hurricane Katrina: implications for clinical practice and disaster management. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:99–104. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318180f14f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kressin NR, Wang F, Long J, et al. Hypertensive patients’ race, health beliefs, process of care, and medication adherence. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:768–774. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0165-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burnier M, Santschi V, Favrat B, Brunner HR. Monitoring compliance in resistant hypertension: an important step in patient management. J Hypertens Suppl. 2003;21:S37–S42. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200305002-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43:521–530. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hawkshead J, Krousel-Wood M. Techniques of measuring medication adherence in hypertensive patients in outpatient settings: advantages and limitations. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2007;15:109–18. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morris AB, Li J, Kroenke K, Bruner-England TE, Young JM, Murray MD. Factors associated with drug adherence and blood pressure control in patients with hypertension. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:483–492. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2007 Chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen RA, Martinez ME. [Accessed September 23, 2012];Health Insurance Coverage: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January–March 2012. Available from http://198.246.124.22/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201209.pdf.

- 46.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119:3028–3035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bokhour BG, Berlowitz DR, Long JA, Kressin NR. How do providers assess antihypertensive medication adherence in medical encounters? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:577–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]