Abstract

One of the major problems associated with the chemotherapy of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) that selectively kills tumor cells is decreased drug resistance. This warranted the development of safe novel pharmacological agents that could sensitize the tumor cells to TRAIL. Here in, we examined the role of aldose reductase (AR) in sensitizing cancer cells to TRAIL and potentiating TRAIL-induced apoptosis of human colon cancer cells. We demonstrate that AR inhibition potentiates TRAIL-induced cytotoxicity in cancer cells by upregulation of both death receptor (DR)-5 and DR4. Knockdown of DR5 and DR4 significantly (>85%) reduced the sensitizing effect of AR inhibitor. fidarestat, on TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Further, AR inhibition also down-regulates cell survival proteins (Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, survivin, XIAP, and FLIP) and up-regulates the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax and alters mitochondrial membrane potential leading to cytochrome-C release, caspases-3 activation and PARP cleavage. We found that AR inhibition regulates AKT/PI3K-dependent activation of forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a. Knockdown of FOXO3a significantly (>80%) abolished AR inhibition-induced upregulation of DR5 and DR4 and apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Overall, our results show that fidarestat, potentiates TRAIL-induced apoptosis through down-regulation of cell survival proteins and upregulation of death receptors via activation of AKT/FOXO3a pathway.

Keywords: Colon cancer, TRAIL, Aldose reductase, Death receptors, apoptosis

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States [1] and [2]. Recent studies have shown that the cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), a member of the tumor necrosis factor gene superfamily, is one of the most-promising experimental cancer therapeutic drugs which selectively kill tumor cells through activation of death receptors [3]. Binding of TRAIL to death receptors DR5 (TRAIL-R2) and DR4 (TRAIL-R1) triggers apoptosis [4]. The death receptors contain a death domain in their cytoplasmic region [5]. Interestingly, the non cancerous cells express mainly decoy receptors DcR1 (TRAIL-R3) and DcR2 (TRAIL-R4) which do not transmit cell death signal [6] and [7]. TRAIL-induced apoptosis pathway, present in cancer cells, involves the recruitment of the adapter protein Fas-associated death domain (FADD) to the DR5 and DR4 and the subsequent recruitment of procaspase-8 forming a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) [8] and [9]. Formation of DISC leads to caspase-8 cleavage and activation of two signaling pathways [10] and [11]. Most cancer cells become less sensitive to TRAIL-induced apoptosis due to modulation or altered expression of death receptors [12] and increased intracellular anti-apoptotic molecules which are involved in blocking the apoptotic signaling pathways, such as cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) [13]. Blocking apoptosis signaling pathway inhibits recruitment of caspase-8 to FADD which inhibits the formation of DISC and or several other anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl2, surviving, XIAP, cIAP-1 and cIAP-2, inhibit active caspases [14]. TRAIL has been shown to be a promising chemotherapeutic drug mainly due to its ability to selectively induce apoptosis of cancer cells without affecting normal cells [15]. Interestingly, the action of TRAIL can be improved by pretreatment with chemotherapeutic drugs or chemopreventive drugs leading to a synergistic apoptotic response in many cancer cells.

Our recent studies indicate that polyol pathway enzyme; aldose reductase (AR, AKR1B1), plays a critical role in mediation of ROS-induced carcinogenic signals. We have shown that the pharmacological AR inhibitors (ARIs), or antisense/siRNA ablation of AR, prevent growth factors-induced proliferation of various colon cancer cells via PLC/PKC/IKK/MAPK/NF-kB/AP-1 [16–18]. Our studies also indicate that the inhibition of AR prevents tumor growth in nude mice xenografts and in azoxymethane (AOM)-treated mice [19]. Thus, our results suggest that ARIs could be useful therapeutically to prevent colon cancer, however, the mechanism by which AR inhibition causes apoptosis in CRC cells is not clearly understood. In this study we have investigated the molecular mechanisms by which AR inhibition sensitizes TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human CRC cells. Our results indicate that AR inhibition using pharmacological inhibitor, fidarestat or AR-siRNA sensitizes HT-29 and HCT-116 colon cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via mitochondrial pathway by increasing cytochrome c release, caspase activation and up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 receptors. Thus, our data suggest that ARIs in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs such as TRAIL could sensitize tumor cells to apoptosis and thus could be a promising approach in preventing CRC growth.

2.0 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Soluble recombinant human TRAIL was purchased from ProSpec-Tany TechnoGene Ltd. McCoys media, PBS, penicillin/streptomycin, trypsin, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Antibodies against DR5, DR4, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, FLIP, cIAP-1, cIAP-2, Bid, Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), caspases, cytochrome c, phospho and total PI3K, Akt, FOXO3a and GAPDH were obtained from Cell Signaling Inc. (Beverly, MA) and Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Fidarestat was obtained as a gift from Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co. Ltd., (Nagoya, Japan). All other reagents used were of analytical grade.

2.2 Cell cultures and cytotoxicity assays

Human colon cancer HT-29, SW-480 and HCT-116 cells were obtained from ATCC and grown in McCoy’s 5A, supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, respectively. For cytotoxicity and apoptosis assay cells were plated in a 96-well plate at 2,500 per well. Cells were growth-arrested in 0.1% FBS with or without ARI, fidarestat (10µM) or transfected with AR-siRNA or scrambled-siRNA using RNAiFect reagent (Qiagen) for 24 h, followed by treatment with TRAIL (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cells incubated with transfection reagent alone served as control. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay and cytotoxicity was measured by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)-cytotoxicity assay kit as per manufacturer’s instructions (BioVision Inc; Milpitas, CA).

2.3. Reverse transcription-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated by using RNeasy® Mini Kit from Qiagen. Equal amount of RNA was used for RT-PCR using Qiagen® one step RT-PCR kit. The gene specific primer (purchased from sigma; Sigma Genosys, USA) sequences were as DR5 sense 5’-AAGACCCTTGTGCTCGTTGTC-3’, DR5 antisense 5’-GACACATTCGATGTCACTCCA-3’, DR4 sense 5’-CTGAGCAACGCAGACTCGCTGTCCAC-3’, DR4 antisense 5’-TCCAAGGACACGGCAGAGCCTGTGCCAT-3’, glyceraldehyde- 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) sense, 5’-GTCTTCACCACCATGGAG-3’ and GAPDH antisense 5’CCACCCTGTTGCTGT AGC-3’. The PCR reaction was carried out in a GeneAmp 2700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, CA) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min; 35 cycles of 94°C 15 s each, 50°C for 30 s, 72°C for 50 s, and then 72°C 10 min for final extension. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis using 1% agarose-1XTAE gels containing 0.5 µg/ml ethidium-bromide. The band intensities were analyzed using Kodak image station densitometry software.

2.4 RNA interference ablation of AR, DR4, DR5 and FOXO3a in colon cancer cells

AR ablation was performed using AR specific siRNA as described earlier [18]. For DR4 and DR5 ablation, briefly, 0.2×106 HT-29 and HCT-116 cells were plated in each well in 6-well plates and allowed to adhere for 24 h. Next day, 50 nmol/liter siRNA (Qiagen) was diluted in 100µl of culture medium in which 12 µl of Hiperfect transfection reagent (Qiagen) was added, mixed by vortexing and incubated for 15 minutes at RT. After 24 h of transfection cells were treated with and without fidarestat followed by stimulation with TRAIL for 24 h. Whole cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting.

2.5 Immunofluorescence microscopy for DR4 and DR5 expression

HT-29 and HCT-116 (0.1× 106 cells/ chamber) were seeded in a chamber slide. Cancer cells were growth-arrested in 0.1 % FBS with or without fidarestat (10µM) overnight. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to TRAIL (100ng/ml) for 24 h. Rabbit anti-DR4 and DR5 antibodies and FITC-labeled secondary antibodies were used to determine the expression of DR4 and DR5.

2.6 Flow cytometry analysis

To analyze the cell-surface expression of DR4 and DR5, phycoerythrin-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-human DR4 and DR5 antibodies were used, which bind to the cells expressing DR4 and DR5, respectively. The cells were washed and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis.

2.7 Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of proteins were loaded to 12% SDS-PAGE followed by transfer of proteins to nitrocellulose filters and probing with the indicated antibodies. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies against DR4, DR5, FADD, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, Bax, cytochrome c, caspase-3 and caspase-8, PI3K, AKT, and FOXO3a. Bands were identified based on their molecular weights. The membranes were stripped using restore plus western blot stripping buffer and re-probed with antibodies against β-Actin/GAPDH to monitor equal protein loading. Antibody binding was detected by enhanced picochemiluminescence (Pierce). Fold changes were calculated by densitometry analysis after normalizing with the respective loading controls.

2.8 Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and active caspase-3

The lipophilic cationic dye JC-1 was used to measure the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). JC-1 exists both, as a green fluorescent monomer in apoptotic or unhealthy cells and a red fluorescent in healthy cells. JC-1 exhibits its membrane potential-dependent accumulation in mitochondria, as indicated by the fluorescence emission shift from 540 to 590 nm. After cells were treated with TRAIL (100 ng/ml) for 24 h in the presence or absence of fidarestat (10µM), 100 µl/ ml JC-1 (1:10) was loaded and was incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and the cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope. For determining of caspase-3 activation, HT-29 and HCT-116 without or with fidarestat (10µM) as well as AR ablated cells were stimulated with TRAIL (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. The level of active caspase-3 was measured using the colorimetric caspase-3 assay kit (Genscript).

2.9 Nude mouse xenografts

The effect of ARI on tumor growth of human colon cancer cells (SW480) in nude mouse xenografts was investigated as described earlier [41]. Briefly, 5- to 6-wk-old athymic nude nu/nu mice (Charles River) were injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 SW480 human colon adenocarcinoma cells in 100 µL of PBS. Animals were treated with fidarestat (50 mg/kg body weight/d), in drinking water when the tumor surface area exceeded approximately 30 mm2 (day 21). All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.10 Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software. For multiple comparisons, ANOVA was performed with post-hoc testing for the desired pair-wise comparisons. For individual pair-wise comparisons the Student’s t test was performed. P< 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3.0 Results

3.1 AR inhibition synergistically increases TRAIL-induced apoptosis of human colon cancer Cells

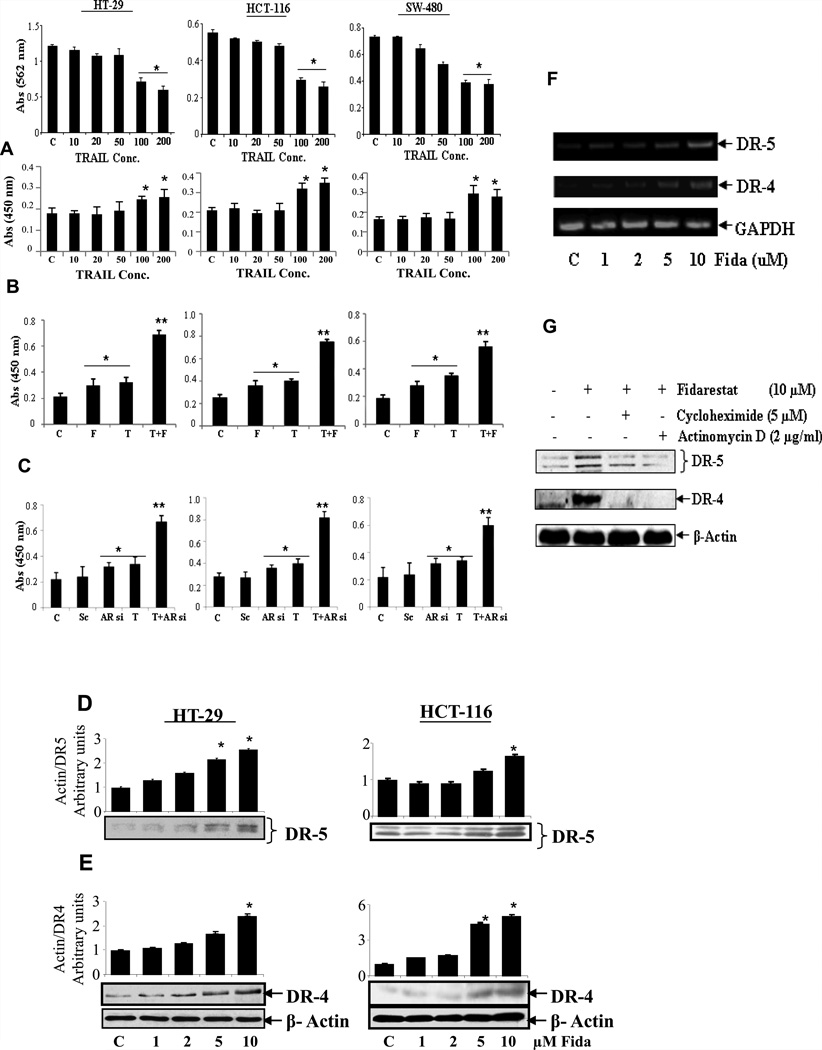

First, we examined the sensitivity of various colon cancer cell lines to TRAIL. Three colon cancer cell lines, HT-29, HCT-116 and SW-480 were treated for 24 h with different concentrations of TRAIL and then assessed for cell viability and death. As shown in Fig.1A, cells were treated with varying concentrations of TRAIL (10–200ng/ml), 100 and 200ng/ml of TRAIL caused decrease in cell viability as measured by MTT assay (50–90%) in all three cell lines. However, cytotoxicity as measured by LDH assay shown that TRAIL is more cytotoxic in HCT116 and SW480 as compared to HT-29 cells. In all our studies, 100ng/ml TRAIL concentration was opted as it caused significant cell death. We next examined the ability of fidarestat (10µM) in sensitizing colon cancer cells to TRAIL-induced cytotoxicity as measured by LDH assay. Our results indicate that fidarestat significantly (>2 fold) increased TRAIL-induced cell death in all three cell lines as compared to fidarestat- or TRAIL alone (Figure 1B). Similarly, AR-siRNA transfected cells TRAIL-induced cytotoxicity of all three cell lines was augmented (Figure 1C). To examine the effect of AR inhibitor fidarestat on TRAIL treatment on non-cancer cells, we incubated HUVEC cells 100 ng/ml without or with 10 uM of fidarestat. Our results shown in the supplementary Fig.1 indicate that TRAIL causes moderate cell death in (~20%) HUVEC and fidarestat prevents TRAIL induced apoptosis. Further to examine synergistic and additive effects of AR inhibitor on TRAIL induced cytotoxicity, we have performed concentration dependent studies. The data shown in the supplementary Fig. 2A indicates increasing concentrations of fidarestat synergistically caused HT-29 cells death in the presence of constant concentration of 100 ng/ml TRAIL. Similarly, increasing concentrations of TRAIL caused HT-29 cells death in the presence of constant concentration of fidarestat 10 uM in HT-29 cells (Supp Fig. 2B). These data indicate that fidarestat and TRAIL are synergistic in causing HT-29 cells death. We next examined, if AR inhibition prevents TRAIL-induced NF-kB activation in colon cancer cells. Our results shown in the Supplementary Fig. 3 indicate that TRAIL caused activation of NF-kB and inhibition of AR by fidarestat prevents it.

Fig. 1. Inhibition or ablation of AR sensitizes colon cancer cells to TRAIL-induced cytotoxicity and up-regulates expression of DR5 and DR4 by increasing transcription and protein stability.

Growth-arrested (A) HT-29, HCT-116 and SW-480 cells were incubated with different concentration (10–200ng/ml) of TRAIL and cell viability was determined by MTT assay (Top) and cytotoxicity was determined by LDH assay (Bottom). (B) untransfected (C) AR-siRNA or scrambled AR-siRNA transfected colon cancer cells were preincubated with and without fidarestat (10µM) overnight followed by stimulation with TRAIL (100ng/ml) for 24 h and cytotoxicity was determined by LDH release. The values given are the mean ± S.D. (n=4). *p < 0.001 Vs control and **p < 0.001 Vs TRAIL and fidarestat alone. (D), HT-29 and (E) HCT-116 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of fidarestat for 24 h and analyzed for expression of DR5 and DR4 by western blotting. (F) HT-29 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of fidarestat for 24 h, and total RNA was extracted and examined for DR5 and DR4 transcripts by RT-PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal control. (G) HCT-116 cells were pretreated with 2µg/ml actinomycin-D or 5µM cycloheximide for 30 min followed by incubation with 10µM fidarestat for 24 h and whole-cell extracts were subjected to western blots using anti-DR5 and anti-DR4 antibodies. A representative blots was shown (n=3 independent experiments). C: Control; F: Fidarestat; T: TRAIL; Sc: Scrambled; AR-si and Si: Aldose reductase-siRNA.

3.2. AR inhibition up-regulates the expression of death receptors in colon cancer cells

Since up-regulation of death receptors such as DR5 and DR4 has been shown to induce apoptosis of colon cancer cells by chemotherapeutic agents including TRAIL, we next examined the effect of AR inhibition on the up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 in human colon cancer cells. As shown in Figure 1D and E, pretreatment of HT-29 and HCT-116 cells with fidarestat up-regulated the expression of DR5 and DR4 in a dose-dependent manner. Further, fidarestat enhanced DR5 and DR4 mRNA levels in HT-29 cells in a dose-dependent manner indicating that ARI affects the transcriptional activation of these receptors (Figure 1F). To determine whether ARI-induced increase in death receptor expression requires de novo protein synthesis or transcriptional activation, we pre-incubated HCT-116 cells with inhibitors of protein synthesis (cycloheximide) and transcription (actinomycin D). Cells were incubated with these inhibitors for 60 min prior to the incubation with ARI for 24 h and the levels of DR5 and DR4 were measured in whole cell lysates. Our results shown in the Figure 1G indicate that pretreatment of cancer cells with the cycloheximide or actinomycin D significantly inhibited fidarestat-induced DR5 and DR4 expression indicating that ARI regulates DR5 and DR4 expression.

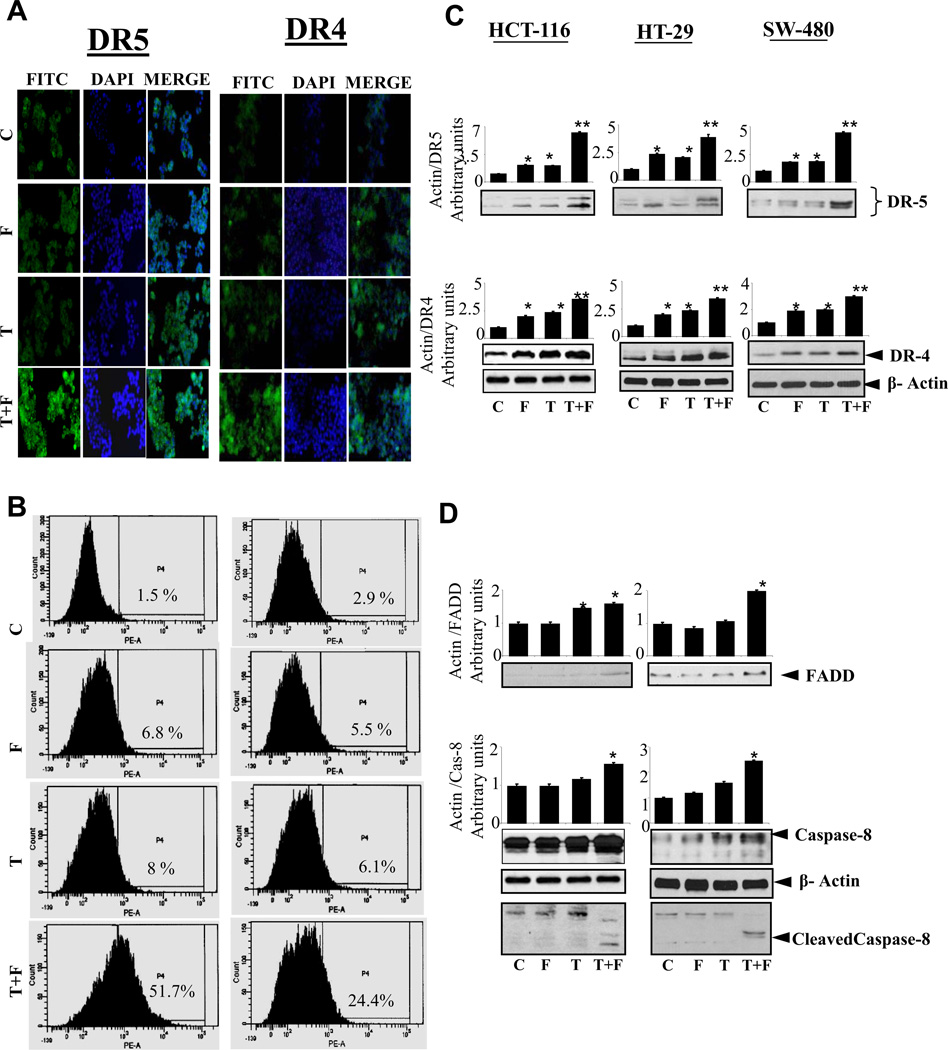

3.3 AR inhibition augments TRAIL-induced death receptors expression and DISC formation

Since chemotherapeutic drugs and various antioxidants have been shown to synergistically enhance TRAIL-induced upregulation of death receptors [20–22], we next examined if AR inhibition works in synergy with TRAIL in induction of death receptors in cancer cells. Our results shown in Figure 2A–B, indicate that pre-incubation of colon cancer cells with ARI significantly enhanced the TRAIL-induced expression of DR5 and DR4 receptors in these cells. Our results indicate that fidarestat in combination with TRAIL significantly increased the cell-surface expression of DR5 and DR4 in HT-29 cells. We next examined if AR inhibition could facilitate the formation of the DISC complex in response to TRAIL stimulation in colon cancer cells. Our results shown in Figure 2C–D indicate that pre-incubation of colon cancer cells with ARI enhanced the TRAIL-induced expression of DR5, 3.5 to 6.3 fold, DR4, 1.4 to 2 fold in HCT-116, HT-29 and SW-480 cells and FADD, 1.6 to 2 fold and caspase-8, 1.5 to 2.4 fold in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. These results suggest that the AR inhibition promotes TRAIL-induced DISC complex in colon cancer cells.

Fig. 2. AR inhibition up-regulates TRAIL-induced cell surface expression of DR5, DR4 and enhances the expression of proteins involved in DISC formation.

Growth-arrested human HT-29 cells were preincubated with and without fidarestat (10µM) overnight followed by stimulation with TRAIL (100ng/ml) for 24 h, cell-surface expression expression of DR5 and DR4 was observed by immunohistochemistry (A) and by flow cytometry (B) using phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated DR5 and DR4 antibodies, magnification 400×. (C-D) Growth-arrested colon cancer cells were preincubated with and without fidarestat (10µM) overnight followed by stimulation with TRAIL (100ng/ml) for 24 h. Western blot analysis was performed using antibodies against anti-DR4, DR5, FADD, caspase-8 and cleaved caspase-8. A representative blots was shown (n=3 independent experiments *P<0.05 and **P<0.001). C: Control; F: Fidarestat; T: TRAIL.

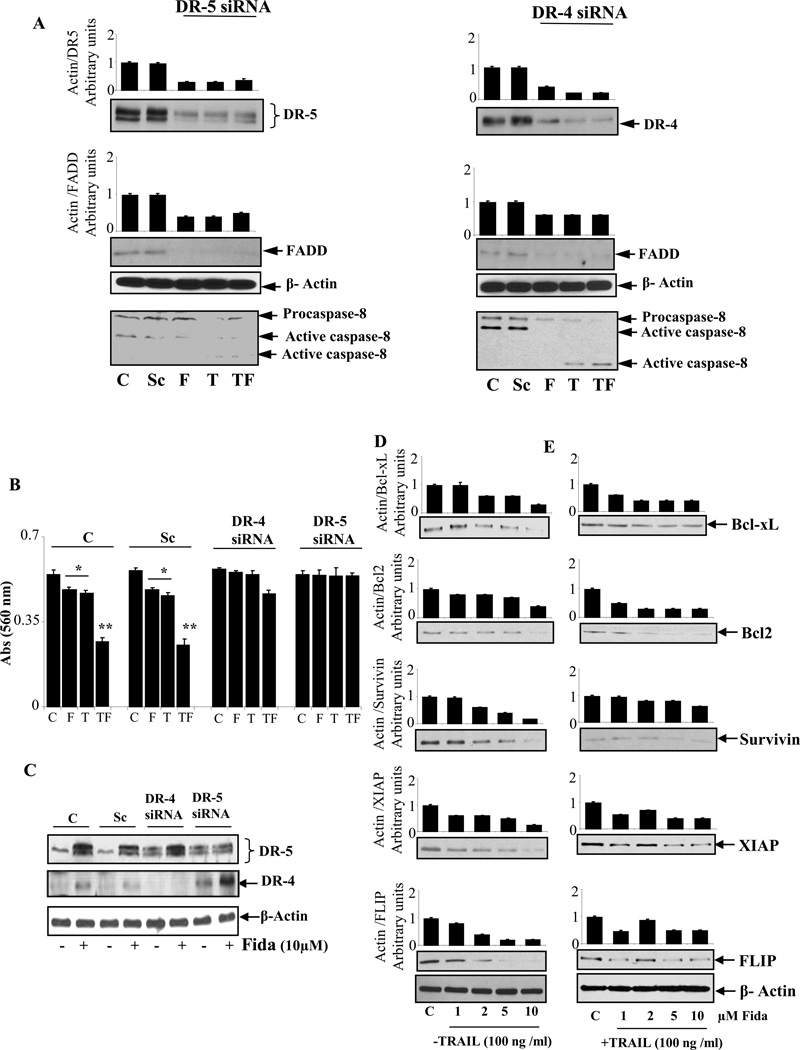

3.4. Knockdown of death receptors abolished the effect of AR inhibition on TRAIL

To evaluate whether the up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 by AR inhibition is essential to sensitize tumor cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis; we ablated DR5 and DR4 in HT-29 cells by using their specific siRNAs. As shown in Fig. 3A, left panel, transfection of cells with DR5 siRNA but not with control siRNA or transfection reagent only control significantly (~70) reduced the fidarestat -induced DR5 up-regulation. Similarly, transfection of cells with DR4 siRNA reduced (~60–80%) the fidarestat -induced DR4 expression (Figure 3A, right panel). We next examined how siRNA-mediated knockdown of DR5 and DR4 affects the AR inhibition-augmented TRAIL-induced DISC formation. As shown in Figure 3A, ablation of DR5 and DR4 in HT-29 cells significantly blocked the fidarestat- or TRAIL –induced expression of FADD and procaspase-8. These results indicate that formation of DISC complex by AR inhibition requires DR5 and DR4. We next examined whether the knockdown of DR5 or DR4 by siRNA could abolish the sensitizing effects of ARI on TRAIL-induced apoptosis of HT-29 colon cancer cells (Fig. 3B–C). The results shown in the Figure 3B indicate that fidarestat significantly augmented the TRAIL-induced apoptosis in control cells and in cells transfected with scrambled siRNA but not in cells transfected with either DR5 or DR4 siRNA.

Fig. 3. AR inhibition abrogates TRAIL-induced apoptosis by ablation of DR5 and DR4 and modulates anti-apoptotic protein expression.

(A) HT-29 cells were transfected with DR5 and DR4 siRNA or scrambled siRNA for 24h or transfection reagent alone (control). Subsequently, cells were treated with and without fidarestat (10µM) followed by stimulation with TRAIL (100ng/ml) for 24 h and analyzed by western blotting using antibodies against anti-DR5, DR4, FADD and procaspase-8. (B) Cell viability was measured by MTT assay *p<0.001 Vs control and **p<0.001 Vs fidarestat and TRAIL alone. (C) Cells were transfected with DR5 and DR4 siRNA or scrambled siRNA 24h, and treated with and without fidarestat (10µM) for another 24 h and analyzed by western blotting using anti-DR5 and anti-DR4 antibodies. (D–E) Growth-arrested HT-29 cells were treated with TRAIL (100 ng/ml) in the absence and presence of different concentrations of fidarestat (0–10µM) for 24 h and analyzed by western blotting using relevant antibodies against Bcl-xl, Bcl2, survivin, XIAP and FLIP. A representative blots was shown (n=3 independent experiments). C: Transfection reagent Control; F and Fida: C+Fidarestat; T: TRAIL, Sc: Scrambled.

3.5 AR inhibition down-regulates the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins linked to TRAIL resistance

We next examined how AR inhibition enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. The intrinsic pathway is controlled by members of the Bcl-2 family associated with the mitochondrial outer membrane and stabilizes mitochondrial integrity and anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, survivin, XIAP and FLIP responsible for TRAIL-resistance in cancer cells [23]. Therefore, we examined whether AR inhibition can modulate the expression of these proteins. Our results showed that fidarestat efficiently down-regulated the expression of Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, survivin, XIAP and FLIP in a concentration-dependent manner in HT-29 cells in the absence and presence of TRAIL (Figure 3D–E).

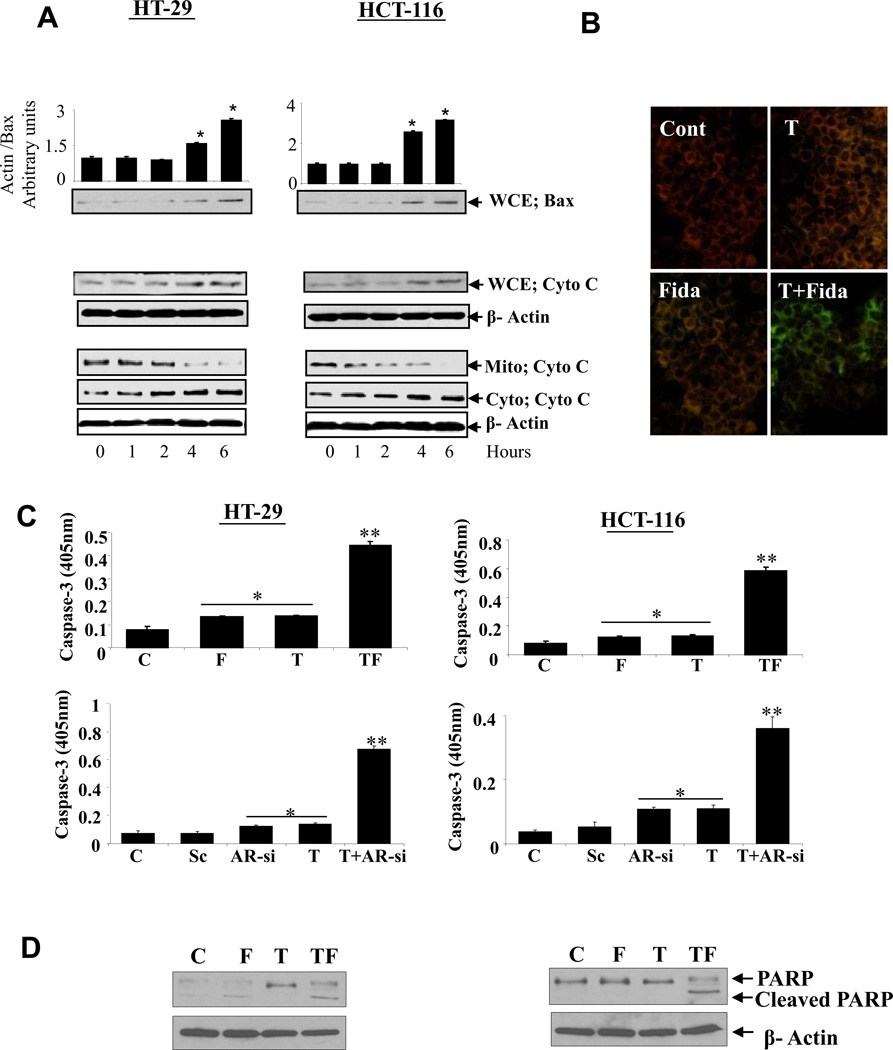

3.6 AR inhibition up-regulates the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax and alter mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) leading to cytochrome c release, caspases-3 activation and PARP cleavage

Upon activation of caspase-8 at the DISC, Bid is cleaved resulting in the generation of its truncated form, t-Bid, which then translocates to the mitochondria and activates Bax leading to the release of cytochrome c [24]. Therefore, we next examined whether AR inhibition can modulate the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins. Indeed, fidarestat increased the expression of Bax up to 3 fold in a time-dependent manner in both HT-29 and HCT-116 cells (Figure 4A, top panel). Treatment of HT-29 cells with fidarestat and TRAIL alone did not cause much chance in ΔΨm. However, decreased ΔΨm was observed when fidarestat and TRAIL were used in combination, as shown by the increase in green fluorescence in Figure 4B. TRAIL caused a marked increase in JC1 fluorescence (green) compared to that of control (red). Since it is well known that the disruption of ΔΨm can cause the release of cytochrome c into the cytosol [25], we next measured cytochrome c in whole cell lysates as well as mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions. As shown in Figure 4A (lower panel), incubation of HT-29 and HCT-116 cells with fidarestat induced the release of cytochrome c in to cytosol from mitochondria in a time-dependent manner. We have also noticed that fidarestat increases the expression of cytochrome c at 4 and 6 h of incubation time in colon cancer cells. Since TRAIL induces apoptosis through the activation of caspases, we next examined the effect of AR inhibition or ablation on the activation of caspase-3 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage in colon cancer cells. As shown in Figure 4C–D, pretreatment of HT-29 and HCT-116 cells with fidarestat or AR-siRNA followed by stimulation with TRAIL increased the caspase-3 activation as compared to control or scrambled siRNA-treated cells. Similarly, the expression of the 89-kDa cleaved fragment of PARP was increased when the cells were treated with ARI in combination with TRAIL as compared to the control cells (Figure 4D). Most importantly, ARI or TRAIL alone had a minimal effect on the activation of caspase-3 and on cleavage of PARP, but the combination of the two was significantly effective in the activation of caspase-3 as well as consequent cleavage of PARP.

Fig. 4. AR inhibition alters mitochondrial membrane potential and increased proapoptotic protein expression activation of caspase-3 and PARP cleavage.

Growth-arrested (A) HT-29 and HCT-116 cells were treated with fidarestat (10µM) for 6h, whole cell extracts, mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were analyzed by western blots using antibodies against Bax and cytochrome c. (B), HT-29 cells were preincubated with and without fidarestat (10uM) overnight followed by stimulation with TRAIL (100ng/ml) for 24h. The lipophilic cationic dye JC-1 was used to measure the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). (C) HT-29 and HCT-116 cells were preincubated with and without fidarestat (10µM) overnight or were transfected with AR-siRNA or scrambled-siRNA for 40 h followed by stimulation with TRAIL (100ng/ml) for another 6h. Caspase-3 activation was measured by using caspase-3 specific ELISA detection kit form Genscript. Bars represent mean ± S.E. (n = 4); *p<0.001 Vs control and **p<0.001 Vs fidarestat or AR-siRNA and TRAIL alone. (D) Cells treated with and without fidarestat and in combination with TRAIL were processed for western blot analysis of the 116-kDa poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and its 89-kDa cleaved fragment. A representative blots was shown (n=3 independent experiments). C: Transfection reagent Control; F: C+ Fidarestat; T: TRAIL, Sc: Scrambled; Mito:mitochondrial fraction; Cyto:cytosolic fraction and WCE: whole cell extract.

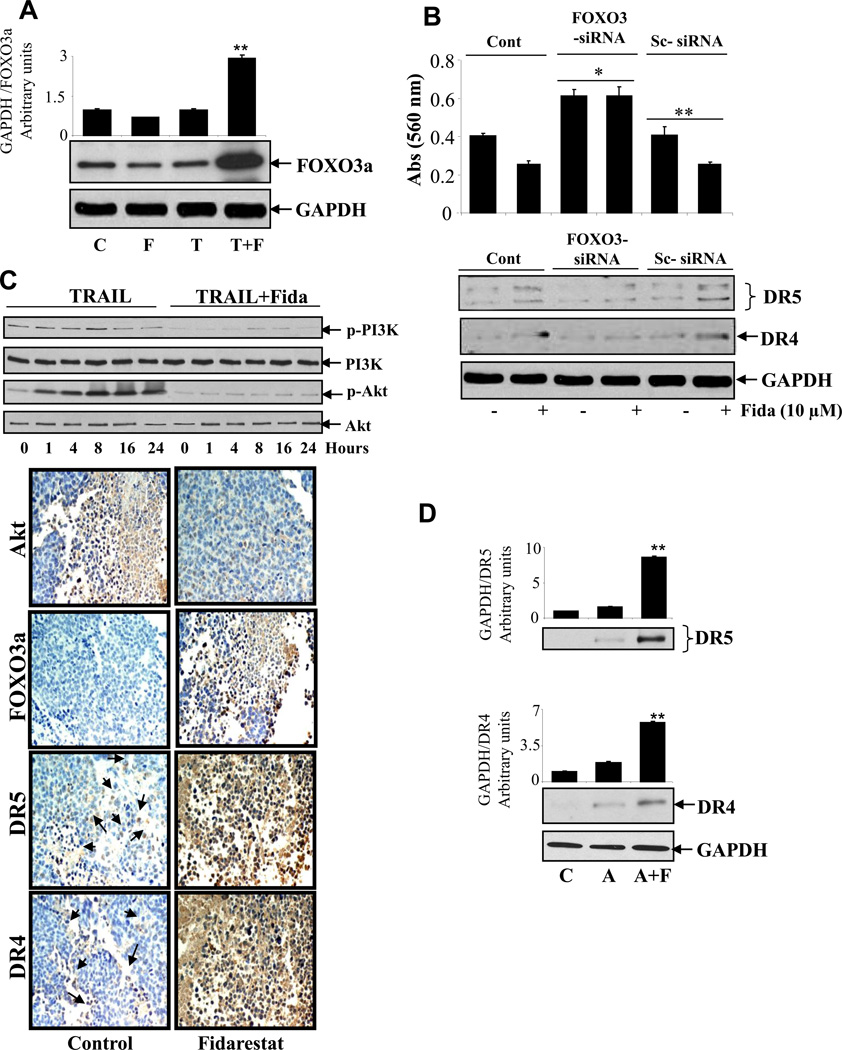

3.7 Effect of AR Inhibition is PI3K/AKT- and FOXO3a-dependent and is required for the execution of apoptosis

Since recent studies indicate that forkhead, FOXO3a transcription factor regulates TRAIL-induced apoptosis [26]; therefore we next examined how AR inhibition affects TRAIL-induced FOXO3a in colon cancer cells. As shown in Figure 5A, pretreatment of HT-29 cells with and without fidarestat followed by stimulation with TRAIL significantly (~3 fold) increased the expression of FOXO3a as compared to cells treated with fidarestat and TRAIL alone. To confirm whether activation of transcription factor FOXO3a plays a crucial role in TRAIL-induced DR5 and DR4 up-regulation as well as apoptosis, we next ablated FOXO3a in HT-29 cells using specific siRNA. As shown in Figure 5B, transfection of cells with FOXO3a siRNA but not with control siRNA transfected cells or transfection reagent only treated cells significantly (>60%) reduced the fidarestat-induced DR5 and DR4 upregulation. Similarly, AR inhibition up regulates the expression of DR5 and DR4 through activation of FOXO3a transcription factor in tumor sections of SW480 nude mice xenografts (Figure 5C, lower panel). Since AKT has been shown to regulate the activation of FOXO3a, we next examined the effect of ARI on TRAIL-induced phosphorylation of PI3K/AKT in colon cancer cells. As shown in Figure 5C, upper panel, treatment with ARI significantly decreased the phosphorylation of PI3K and AKT in colon cancer cells. Similar results were observed in xenograft tumor sections. As described by us recently [19], we have examined the expression of death receptors in the normal as well as azoxymethane (AOM)-induced colon carcinoma. Our results shown that as compared to colon tissues from normal and AOM treated mice, the colon tissues from ARI+AOM treated mice showed a significant increased expression of DR4 and DR5 (Figure 5D). These results thus suggest that AR inhibition via PI3K/AKT could regulate the activation of FOXO3a transcription factor which plays a key role in sensitizing tumor cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by up regulating DR5 and DR4.

Fig. 5. Up-regulation of DR4 and DR5 by AR inhibition is mediated through the PI3K/AKT pathway.

Growth-arrested (A) HT-29 cells were preincubated with and without fidarestat (10uM) followed by stimulation with TRAIL (100ng/ml) for 24h, and whole-cell extracts were analyzed by western blotting using antibodies against FOXO3a. (B), Ablation of FOXO3a abrogated AR inhibition-induced expression of DR5 and DR4. HT-29 cells were transfected with FOXO3a siRNA and scrambled siRNA for 24h followed by treatment with and without fidarestat (10uM) for another 24h. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay and whole-cell extracts were analyzed by western blotting using anti-DR5, DR4 and GAPDH antibodies. (C) HT-29 cells were preincubated with and without fidarestat (10uM) followed by stimulation with TRAIL (100ng/ml) from 0–24h. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed by western blotting using antibodies against phospho and total PI3K and AKT. Cross sections of xenograft tumors were stained with anti-AKT, anti-FOXO3a, anti-DR5, and anti-DR4. Dark brown stain is evident of immunoreactivity, whereas non-reactive areas display only the background color. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (blue). Original magnification, 400×. Photomicrographs of the stained sections were acquired using an EPI-800 microscope (bright-field) connected to a Nikon camera. (D) Normal, AOM and AOM+fidarestat treated mice colons were processed to analyze the expression of the death receptors by Western blot analysis using anti-DR4 and DR-5 antibodies.

4.0 Discussion

The main criterion of chemotherapy in cancer is based upon the higher susceptibility of the cancerous cells to apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs compared to normal cells. However, the biochemical mechanisms for increased susceptibility of cancerous cells to apoptosis are not clearly understood. We have recently shown that inhibition of AR prevents proliferation of cancer cells in culture as well as in nude mice xenografts indicating that the ARIs could be chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic [27] and [28]. In the present study, we for the first time report the novel role of AR in 1) sensitizing human colon cancer cells to apoptosis and 2) enhancing the chemotherapy potential of TRAIL. We demonstrate that the inhibition of AR significantly enhanced the TRAIL-induced apoptosis by up-regulating the expression of both the TRAIL receptors, DR4 and DR5. Further, we show that the AR inhibition enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells through a variety of mechanisms that include formation of disc complex, down-regulation of Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, survivin, FLIP, and XIAP; induction of bax and cytochrome c release; down-regulation of PI3K/AKT and up-regulation of FOXO3a. These studies indicate that AR inhibition in combination with TRAIL -increases apoptosis of colon cancer cells.

We have shown earlier that AR inhibition prevents cancer cell growth by inducing apoptosis of human colon cancer cells [28]. However, the intracellular pathways by which AR inhibition causes apoptosis remain unknown. In this study we found that the inhibition of AR can induce colon cancer cell apoptosis by up-regulating pro-apoptotic protein, Bax which results in the translocation of cytochrome c from the mitochondria to the cytosol by altering mitochondrial permeability transition and upregulation of caspase-9. Thus, our results indicate that AR inhibition causes apoptosis in colon cancer cells by mitochondrial- mediated apoptosis pathway. Further, our studies also indicate that AR inhibition alone or in combination with TRAIL activates caspase-8 indicating that AR inhibition also triggers death receptor -mediated apoptotic pathway. Thus, our studies indicate a novel role of AR in regulating both death receptor-mediated pathway and mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis in cancer cells. Recent studies indicate that several antioxidants cause apoptosis of cancer cells by either mitochondrial or death receptor – mediated pathways [29] and [30]. Several studies also report some chemotherapeutic agents such as nimbolide, and celastrol could activate both the pathways [31] and [32]. A recent study suggests that low concentrations of chemotherapeutic drug, cisplatin activate the death receptor-mediated pathway, whereas moderate concentrations activate the mitochondrial pathway [33]. Even though, we have shown that AR down regulates anti-apoptotic survival proteins in non cancerous cells [34], the mechanism by which these survival proteins are down-regulated by AR inhibition is not clear. Since the expressions of most of the anti-apoptotic proteins is regulated by redox sensitive transcription factor, NF-κB, and a number of NF-kB inhibitors have been found to down-regulate the expression of cell survival proteins [35], AR inhibition could cause down-regulation of survival proteins by inhibiting the NF-kB transcriptional activity in colon cancer cells. Indeed, we have already shown that AR inhibition suppresses NF-κB activation in colon cancer as well as in other cells [36]. Therefore, it is possible that down-regulation of expression of these proteins by AR inhibition could be through the down-regulation of NF-κB. Further, over expression of Bax causes apoptosis in cancer cells [37]. We have found that AR inhibition significantly upregulated the expression of Bax which has been shown to be a critical protein involved in the TRAIL-induced apoptosis.

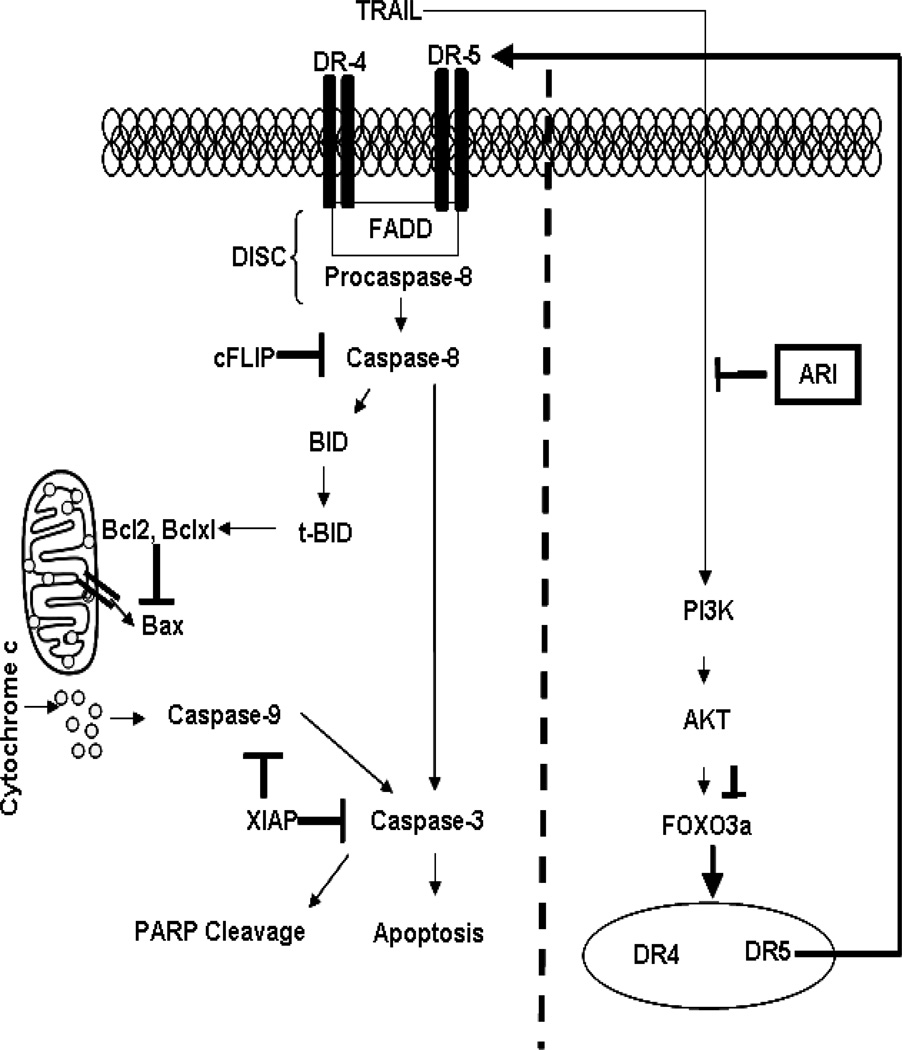

Several studies have demonstrated that FOXO transcription factors are constitutively activated in different human malignancies [38]. Activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway is known to results in inactivation of tumor suppressor’s transcription factors FOXO in the majority of human cancers [39] and [40]. Increased activity of the AKT and ERK kinases leading to increased constitutive FOXO activity has been reported in prostate cancer cells [41]. Activation of FOXO induces apoptosis by regulating the expression of genes such as FasL, TRAIL, DR4, and DR5 [26]. Previous studies have suggested that increased activation of AKT and its upstream regulator PI3K results in increased TRAIL resistance in cancer cells [42]. However, the underlying mechanism is not fully understood. AKT-dependent phosphorylation of FOXO promotes FOXO transport from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [41]. In the present study, we have demonstrated that inhibition of AKT activation by ARI transformed TRAIL-resistant cells to TRAIL-sensitive cells by up-regulating DR4 and DR5 receptors (Figure-6). We also observed that inhibition of AR inhibited AKT activation by inhibiting upstream PI3K in TRAIL-resistant human colon cancer cells. Since PI3K serves as an upstream positive regulator of AKT, our results show that inhibiting AKT activation results in increased activation of FOXO3a transcription factor leading to up-regulation of TRAIL receptors, DR4 and DR5. It is well known that many colon cancer cells including HT-29 are resistant to TRAIL -induced apoptosis. However, our results revealed that AR inhibition renders TRAIL-resistant HT-29 and HCT-116 colon cancer cells sensitive to proapoptotic TRAIL stimulation by up-regulating the TRAIL receptors, DR4 and DR5 via FOXO3a. Similarly, Ghaffari S et al., have reported that resistance of colon cancer cells to TRAIL was abolished by inhibition of AKT-mediated regulation of FOXO3a [43].

Fig. 6. Schematic diagram showing AR inhibition sensitizes human colon cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through both, extrinsic and intrinsic pathway.

Overall, our study shows that ARIs could potentiate the apoptotic effects of TRAIL through activation of multiple pathways including expression of death receptors, up-regulation of pro-apoptotic proteins, and inhibition of anti-apoptotic proteins. Furthermore, AR inhibition inhibits PI3K/AKT activation resulting in the activation of transcription factor FOXO3a involved in transcribing genes for DR4 and DR5. We have also shown that AR inhibition is not effective in the expression of DR4 and DR5 in cells knockdown of FOXO3a using specific siRNA. These results suggest that the AR inhibition causes apoptosis in colon cancer cells by PI3K/AKT/FOXO3a -dependent pathway. These and our previous studies-indicating that AR inhibition prevents colon cancer growth and metastasis [18, 44] strongly suggest that ARIs, which have been thought to prevent diabetic complications, could be potential chemotherapeutic drugs. Since ARIs such as fidarestat which have gone through a 52 weeks Phase-3 clinical studies for the diabetic neuropathy and found to be safe for human use without any major irreversible side effects, the ARIs could be developed as a potential chemotherapeutic drug alone or in combination with TRAIL to prevent colon cancer. Further, ARIs could also be used to enhance potential of chemotherapeutic drugs to TRAIL –resistant colon cancer.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Aldose reductase (AR) inhibitor enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis of colon cancer cells.

AR inhibition increases the death receptors (DR4 and DR5) in colon cancer cells.

AR inhibition down-regulates survival proteins and up-regulates pro-apoptotic proteins.

AR inhibition regulates AKT/PI3K-dependent activation of forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a in colon cancer cells.

AR inhibitors enhances chemotherapeutic efficacy of TRAIL.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

Supported by in parts by NIH grants (CA129383 and DK36118 to S.K.S.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosers: None

Declarations: None

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peter ME. Taming TRAIL: the winding path to a novel form of cancer therapy. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2005;12:693–694. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahalingam D, Keane M, Pirianov G, Mehmet H, Samali A, Szegezdi E. Differential activation of JNK1 isoforms by TRAIL receptors modulate apoptosis of colon cancer cell lines. British Journal of Cancer. 2009;100:1415–1424. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker SJ, Reddy EP. Modulation of life and death by the TNF receptor superfamily. Oncogene. 1998;17:3261–3270. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan G, Ni J, Wei YF, Yu G, Gentz R, Dixit VM. An antagonist decoy receptor and a death domain-containing receptor for TRAIL. Science. 1997;277:815–818. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheridan JP, Marsters SA, Pitti RM, Gurney A, Skubatch M, Baldwin D, Ramakrishnan L, Gray CL, Baker K, Wood WI, Goddard AD, Godowski P, Ashkenazi A. Control of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by a family of signaling and decoy receptors. Science. 1997;277:818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scaffidi C, Medema JP, Krammer PH, Peter ME. FLICE is predominantly expressed as two functionally active isoforms, caspase-8/a and caspase-8/b. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26953–26958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodmer JL, Holler N, Reynard S, Vinciguerra P, Schneider P, Juo P, Blenis J, Tschopp J. TRAIL receptor-2 signals apoptosis through FADD and caspase-8. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:241–243. doi: 10.1038/35008667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scaffidi C, Fulda S, Srinivasan A, Friesen C, Li F, Tomaselli KJ, Debatin KM, Krammer PH, Peter ME. Two CD95 (APO-1/Fas) signaling pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:1675–1687. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Zhu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J. Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 1998;94:491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner KW, Punnoose EA, Januario T, Lawrence DA, Pitti RM, Lancaster K, Lee D, von Goetz M, Yee SF, Totpal K, Huw L, Katta V, Cavet G, Hymowitz SG, Amler L, Ashkenazi A. Death-receptor O-glycosylation controls tumor-cell sensitivity to the proapoptotic ligand Apo2L/TRAIL. Nat Med. 2007;9:1070–1077. doi: 10.1038/nm1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irmler M, Thome M, Hahne M, Schneider P, Hofmann K, Steiner V, Bodmer JL, Schröer M, Burns K, Mattmann C, Rimoldi D, French LE, Tschopp J. Inhibition of death receptor signals by cellular FLIP. Nature. 1997;388:190–195. doi: 10.1038/40657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature. 1997;388:300–304. doi: 10.1038/40901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowinsky EK. Targeted induction of apoptosis in cancer management: the emerging role of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor activating agents. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9394–9407. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srivastava SK, Ramana KV, Bhatnagar A. Role of aldose reductase and oxidative damage in diabetes and the consequent potential for therapeutic options. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:380–392. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramana KV, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava S. Mitogenic responses of vascular smooth muscle cells to lipid peroxidation-derived aldehyde 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal (HNE): role of aldose reductase-catalyzed reduction of the HNE-glutathione conjugates in regulating cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17652–17660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tammali R, Ramana KV, Singhal SS, Awasthi S, Srivastava SK. Aldose reductase regulates growth factor-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 production in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;6:9705–9713. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tammali R, Reddy AB, Ramana KV, Petrash JM, Srivastava SK. Aldose reductase deficiency in mice prevents azoxymethane-induced colonic preneoplastic aberrant crypt foci formation. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:799–807. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamat AM, Tharakan ST, Sung B, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin potentiates the antitumor effects of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin against bladder cancer through the downregulation of NF-kappaB and upregulation of TRAIL receptors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8958–8966. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Psahoulia FH, Drosopoulos KG, Doubravska L, Andera L, Pintzas A. Quercetin enhances TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in colon cancer cells by inducing the accumulation of death receptors in lipid rafts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2591–2599. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rushworth SA, Micheau O. Molecular crosstalk between TRAIL and natural antioxidants in the treatment of cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:1186–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prasad S, Yadav VR, Ravindran J, Aggarwal BB. ROS and CHOP are critical for dibenzylideneacetone to sensitize tumor cells to TRAIL through induction of death receptors and downregulation of cell survival proteins. Cancer Res. 2011;71:538–549. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Falschlehner C, Emmerich CH, Gerlach B, Walczak H. TRAIL signalling: decisions between life and death. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1462–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim KH, Seo HS, Choi HS, Choi I, Shin YC, Ko SG. Induction of apoptotic cell death by ursolic acid through mitochondrial death pathway and extrinsic death receptor pathway in MDA-MB-231 cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34:1363–1372. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0817-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Q, Ganapathy S, Singh KP, Shankar S, Srivastava RK. Resveratrol induces growth arrest and apoptosis through activation of FOXO transcription factors in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tammali R, Saxena A, Srivastava SK, Ramana KV. Aldose reductase inhibition prevents hypoxia-induced increase in hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by regulating 26 S proteasome-mediated protein degradation in human colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:24089–24100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramana KV, Tammali R, Srivastava SK. Inhibition of aldose reductase prevents growth factor-induced G1-S phase transition through the AKT/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/E2F-1 pathway in human colon cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:813–824. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh YC, Rao YK, Whang-Peng J, Huang CY, Shyue SK, Hsu SL, Tzeng YM. Antcin B and its ester derivative from Antrodia camphorata induce apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells involves enhancing oxidative stress coincident with activation of intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:10943–10954. doi: 10.1021/jf202771d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeh RD, Chen JC, Lai TY, Yang JS, Yu CS, Chiang JH, Lu CC, Yang ST, Yu CC, Chang SJ, Lin HY, Chung JG. Gallic acid induces G0/G1 phase arrest and apoptosis in human leukemia HL-60 cells through inhibiting cyclin D and E, activating mitochondria-dependent pathway. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:2821–2832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta SC, Reuter S, Phromnoi K, Park B, Hema PS, Nair M, Aggarwal BB. Nimbolide sensitizes human colon cancer cells to TRAIL through reactive oxygen species- and ERK-dependent up-regulation of death receptors, p53, and Bax. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1134–1146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.191379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Sung B, Park B, Yadav VR, Aggarwal BB. Celastrol, a triterpene, enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis through the down-regulation of cell survival proteins and up-regulation of death receptors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11498–11507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Tsuruya K, Tokumoto M, Ninomiya T, Hirakawa M, Masutani K, Taniguchi M, Fukuda K, Kanai H, Hirakata H, Iida M. Antioxidant ameliorates cisplatin-induced renal tubular cell death through inhibition of death receptor-mediated pathways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F208–F218. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00311.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramana KV, Reddy AB, Tammali R, Srivastava SK. Aldose reductase mediates endotoxin-induced production of nitric oxide and cytotoxicity in murine macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1290–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aggarwal S, Ichikawa H, Takada Y, Sandur SK, Shishodia S, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) down-regulates expression of cell proliferation and antiapoptotic and metastatic gene products through suppression of IkappaBalpha kinase and Akt activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:195–206. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoeb M, Yadav UC, Srivastava SK, Ramana KV. Inhibition of aldose reductase prevents endotoxin-induced inflammation by regulating the arachidonic acid pathway in murine macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1686–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin PH, Pan Z, Zheng L, Li N, Danielpour D, Ma JJ. Overexpression of Bax sensitizes prostate cancer cells to TGF-beta induced apoptosis. Cell Res. 2005;15:160–166. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Der Heide LP, Hoekman MF, Smidt MP. The ins and outs of FoxO shuttling: mechanisms of FoxO translocation and transcriptional regulation. Biochem J. 2004;380:297–309. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dansen TB, Burgering BM. Unravelling the tumor-suppressive functions of FOXO proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arcaro A, Guerreiro AS. The Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Pathway in Human Cancer: Genetic Alterations and Therapeutic Implications. Curr Genomics. 2007;5:271–306. doi: 10.2174/138920207782446160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ganapathy S, Chen Q, Singh KP, Shankar S, Srivastava RK. Resveratrol enhances antitumor activity of TRAIL in prostate cancer xenografts through activation of FOXO transcription factor. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15627. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen KF, Yeh PY, Hsu C, Hsu CH, Lu YS, Hsieh HP, Chen PJ, Cheng AL. Bortezomib overcomes tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells in part through the inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11121–11133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806268200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghaffari S, Jagani Z, Kitidis C, Lodish HF, Khosravi-Far R. Cytokines and BCR-ABL mediate suppression of TRAIL-induced apoptosis through inhibition of forkhead FOXO3a transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6523–6528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0731871100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tammali R, Reddy AB, Saxena A, Rychahou PG, Evers BM, Qiu S, Awasthi S, Ramana KV, Srivastava SK. Inhibition of aldose reductase prevents colon cancer metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1259–1267. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.