Abstract

Objectives

We evaluated the implementation of three commericially available neuraminidase inhibition assays in a public health laboratory (PHL) setting. We also described the drug susceptibility patterns of human influenza A and B circulating in Maryland during the 2011–2012 influenza season.

Methods

From January to May 2012, 169 influenza virus isolates were tested for phenotypic susceptibility to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir using NA-FluorTM, NA-Star®, and NA-XTDTM concurrently. A 50% neuraminidase inhibitory concentration (IC50) value was calculated to determine drug susceptibility. We used the standard deviation based on the median absolute deviation of the median analysis to determine the potential for reduced drug susceptibility. We evaluated each assay for the use of resources in high- and low-volume testing scenarios.

Results

One of the 25 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic isolates tested was resistant to oseltamivir and peramivir, and sensitive to zanamivir, on all three platforms. Eighty-two influenza A (H3N2) and 62 B isolates were sensitive to all three drugs in all three assays. For a low-volume scenario, NA-Star and NA-XTD took 120 minutes to complete, while NA-Fluor required 300 minutes to complete. The lowest relative cost favored NA-Star. In a high-volume scenario, NA-Fluor had the highest throughput. Reagent use was most efficient when maximizing throughput. Cost efficiency from low- to high-volume testing improved the most for NA-Star.

Conclusions

Our evaluation showed that both chemiluminescent and fluorescent neuraminidase inhibition assays can be successfully implemented in a PHL setting to screen circulating influenza strains for neuraminidase inhibitor resistance. For improved PHL influenza surveillance, it may be essential to develop guidelines for phenotypic drug-resistance testing that take into consideration a PHL's workload and available resources.

This article contributes to the understanding of influenza drug resistance by describing the phenotypic susceptibility of human influenza A and B viruses to two commonly used neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs), oseltamivir (Tamiflu®, Genentech, San Francisco, California) and zanamivir (RelenzaTM, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina), and one investigational NAI, peramivir (BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, Durham, North Carolina), as observed during the 2011–2012 influenza season. We evaluated the implementation of three neuraminidase inhibition (NI) assays (NA-FluorTM Influenza Neuraminidase Assay Kit, NA-Star® Influenza Neuraminidase Inhibitor Resistance Detection Kit, and NA-XTDTM Influenza Neuraminidase Assay Kit [Life Technologies Corp., Carlsbad, California]) for the detection of phenotypic influenza antiviral drug resistance in a public health laboratory (PHL) setting.

Currently, two classes of antiviral drugs for chemoprophylaxis and treatment of human influenza viruses are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Adamantanes were the first to be developed and include amantidine and a methyl derivative, rimantidine. Widespread resistance of circulating influenza viral strains to the adamantane drug compounds has paved the way for reliance on a class of drugs called NAIs, which target the envelope glycoprotein neuraminidase (NA) required for viral replication and successful establishment of infection. The FDA-approved NAIs include oseltamivir, which is administered orally, and zanamivir, which is administered through inhalation directly to the site of the viral replication.2,3 Additionally, the FDA-investigational NAI, peramivir, which is administered intravenously, is available under the Emergency Use Act for treatment of severe cases of influenza during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic (hereafter, influenza A [H1N1]pdm09).4

Due to differing chemical structures, oseltamivir requires NA to undergo a conformational change that effectively inhibits NA, whereas zanamivir does not. NA mutations that alter the oseltamivir binding domain may affect the virus's ability to adjust the required conformational changes, which translate as oseltamivir resistance. The differences in the mode of action have been attributed to the higher probability of oseltamivir encountering resistance.5 This vulnerability became apparent during the 2007–2008 influenza season in the United States, when an H275Y mutation characterized in the NA gene of the seasonal influenza A (H1N1) virus displayed patterns of near-universal oseltamivir resistance.6 However, during the influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 in the U.S., drug resistance to oseltamivir was detected in <1% of tested influenza A (H1N1) strains.6 Resistance was correlated with hospitalized and immunocompromised individuals with prior exposure to oseltamivir.7–9

There have only been isolated and sporadic incidences of influenza A (H1N1), influenza A (H3N2), and influenza B viruses' resistance to zanamivir. Additionally, peramivir is still in clinical trials in the U.S., and resistance patterns have not been fully established. However, in vitro cross-resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir has been reported in influenza A (H1N1) strains with the H275Y mutation.10 To date, seasonal influenza strains remain largely susceptible to both oseltamivir and zanamivir.11

METHODS

Viruses, cells, and reagents

During the 2011–2012 influenza season,12 at the State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (MD DHMH) Laboratories Administration Division of Virology and Immunology, available seasonal influenza virus isolates (n=169) were propagated in primary rhesus monkey kidney cell lines (Diagnostic Hybrids, Athens, Ohio) and were stored at ≤–70°C for use in NAI susceptibility testing. The 169 isolates were previously identified as influenza A (H3N2) (n=82), influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 (n=25), and influenza B (n=62) by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) at the MD DHMH Laboratories Administration Division of Molecular Biology. Each influenza virus isolate was tested for NAI susceptibility using one fluorescent-based NI assay (NA-Fluor) and two chemiluminescent-based NI assays (NA-Star and NA-XTD) against three NAIs. The NAIs were oseltamivir as the active metabolite oseltamivir carboxylate (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), and peramivir. The 96-well assay plates were read using the VictorTM X4 Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Shelton, Connecticut). The measurements were reported as the concentration of NAIs required to inhibit 50% of the NA activity, called an inhibitory concentration (IC50) value. An influenza virus isolate reference panel including the IC50 values was kindly provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Table 1). The MD DHMH Laboratories Administration Division of Virology and Immunology reconfirmed the established range of IC50 values for each NAI in the reference panel listed in Table 1 with the three NI assays (Table 2).

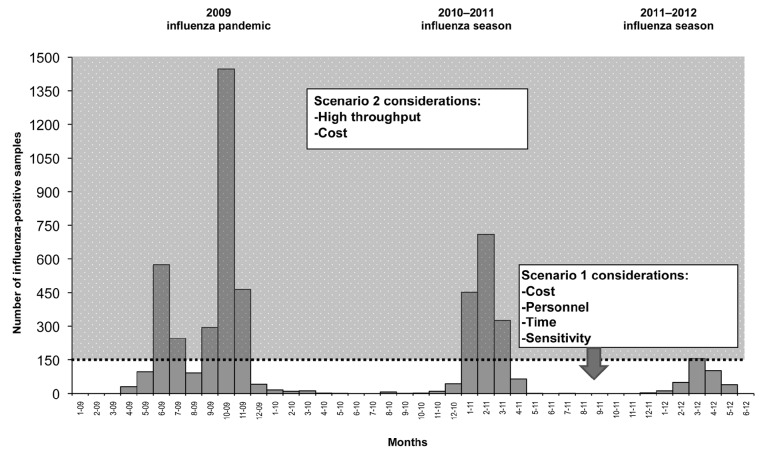

Table 1.

Expected IC50 values (nM) for reference strains using fluorescent and chemiluminescent neuraminidase inhibition assays against oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir as provided by CDC to MD DHMH Laboratories Administration in 2011, unless otherwise noteda

aIC50 values from Okomo-Adhiambo M, Sleeman K, Ballenger K, Nguyen HT, Mishin VP, Sheu TG, et al. Neuraminidase inhibitor susceptibility testing in human influenza viruses: a laboratory surveillance perspective. Viruses 2010;2:2269-89.

IC50 = 50% inhibitory concentration

nM = nanomolar

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

MD DHMH = State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

pdm09 = 2009 pandemic

NA = not available

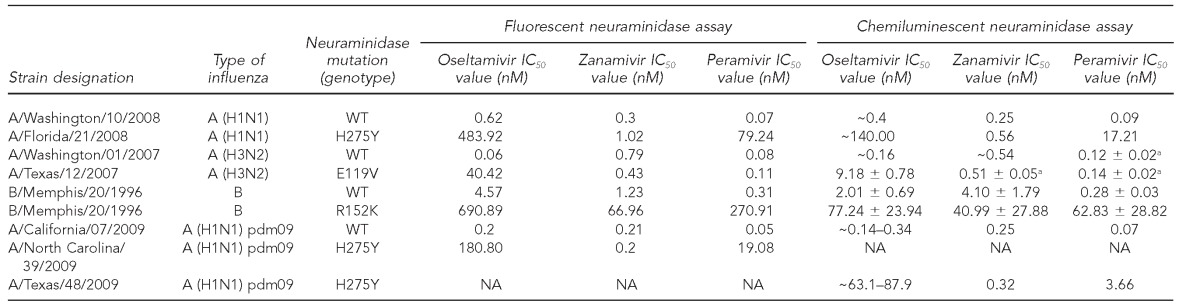

Table 2.

Observed IC50 values (nM)a for reference strains obtained from CDC tested using three commercially available neuraminidase inhibition assays against oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir at the MD DHMH Laboratories Administration in 2011

aIC50 values are the mean of three independent assays.

IC50 = 50% inhibitory concentration

nM = nanomolar

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

MD DHMH = State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

NA = neuraminidase

pdm09 = 2009 pandemic

NI assays

The fluorescent NI assay, NA-Fluor, and the chemiluminescent NI assays, NA-Star and NA-XTD, are used to monitor phenotypic influenza NA susceptibility. The manufacturers' protocols were followed for NA-Fluor, NA-Star, and NA-XTD.13–15 These assays provide a quantitative measurement of how well an NAI inhibits the activity of the viral NA as a means of assessing an isolates' relative susceptibility. Variables that affect the IC50 value ranges for each NAI include influenza subtype, associated NA mutations, and NI assay.16–18

Both NA-Star and NA-XTD use a 1,2 dioxetane derivative of sialic acid as a substrate. The NA-XTD substrate provides about 12 times more signal stability than NA-Star. Moreover, the sensitivity of these two chemiluminescent substrates is five- to 50-fold higher by the signal-to-noise ratio than the fluorescent-based assay.13,14 NA-Fluor uses the fluorogenic reagent 2'-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-a-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid substrate with a 240-minute signal stability at room temperature.15 NA-Fluor required the generation of a 4-Methylumbelliferone sodium salt (4-MU [SS]) standard curve to determine the linear range of substrate turnover detection of the Victor X4 Multilabel Plate Reader. The raw data were plotted on a scatter-plot graph as relative fluorescent units (RFUs) vs. 4-MU (SS) concentration using Microsoft® Excel. The NA activity/RFU range corresponding to 10 micromolar 4-MU (~200,000 RFU) was determined as the set point for the optimal viral dilution factor obtained from the following pretitration step.

As a result of the substrate differences, the IC50 values of fluorescent vs. chemiluminescent NI assays were comparable only in their interpretations of drug susceptibility; thus, no absolute and comprehensive measure of resistance has been established.19 However, elevated IC50 values were indicative of reduced susceptibility.

Data analysis

The IC50 values were calculated using JASPR version 1.2 according to the equation V=Vmax* (1-([I]/(Ki + I))), and a best-fit dose-response curve was generated.19,20 An observed IC50 value greater than the cutoff of threefold above the expected wild-type IC50 value (Table 1) was established as one criteria for interpreting isolates as having reduced susceptibility to a given drug compound (i.e., resistant).20 If a sample's IC50 concentrations were greater than threefold higher than the subtype-specific reference range, the sample was retested to confirm the result. If data points did not fall along the best-fit curve in the IC50 graph, the sample was retested.

An additional criterion for determining the relevance of IC50 values that differ quantitatively from the wild-type reference strains is to identify cutoff values for mild outliers and outliers based on seasonal observations, as an indication of the potential for resistance to a given NAI. The cutoff values for each influenza strain type were calculated using a standard deviation (SD) based on the median absolute deviation of the median (SMAD) analysis of the common logarithm (log10) transformed NAI-specific IC50 values for each assay. SMAD analysis was performed using all data from the influenza isolates considered susceptible according to the first criterion of an IC50 value within threefold of the expected wild-type strains. Log transformation was necessary because IC50 values were not considered normally distributed. The SMAD-determined cutoff for mild outliers was set at median +1.65SD and outliers as median +3SD. Results were back-transformed and the SD was presented. Influenza isolates with IC50 values greater than tenfold were excluded from SMAD analysis as well as calculations of the mean and median. The second criterion for resistance was defined as an IC50 value that was both 3SD and ≥tenfold above the seasonal strain-specific median.21

Assay evaluation

Each NI assay was evaluated for its impact on resources (i.e., time, reagents, cost, supplies, and personnel) based on two testing scenarios and workflow. Both scenarios assumed testing against three NAIs, one plate per NAI, and eight samples per plate (including one NAI-sensitive and one NAI-resistant control per day), performed by one technologist. Scenario 1 evaluated the three assays for a period of low volume of influenza virus isolates for testing, where testing was limited to a maximum daily throughput of six specimens including two controls. Scenario 2 was evaluated for a period of high volume of influenza virus isolates, in which the total assay time and the hands-on technologist time were considered to be equal. Lastly, we evaluated the relative cost per isolate. Possible implementation guidelines for a PHL setting were applied to influenza A (H1N1) pdm09, the 2010–2011 influenza season, and the 2011–2012 influenza season as examples.

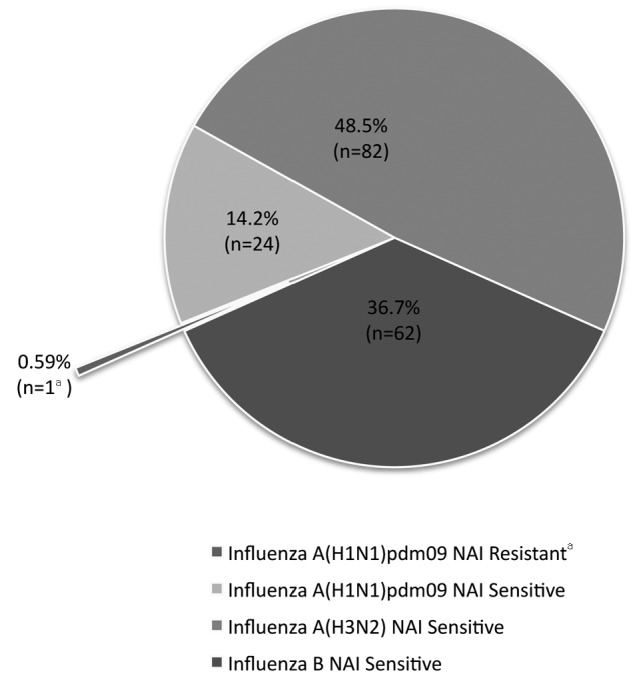

RESULTS

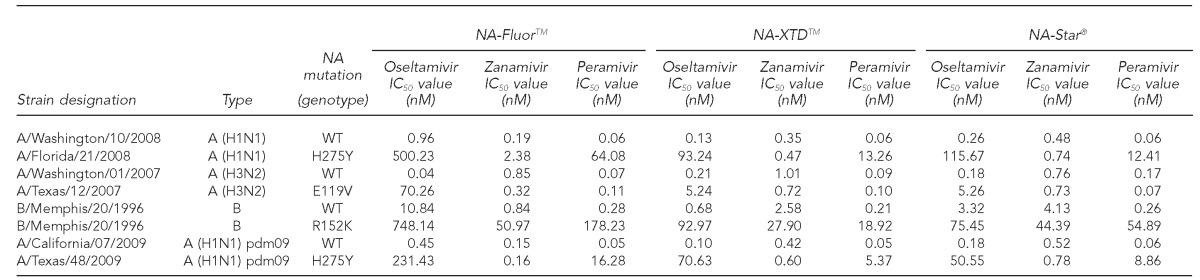

A total of 169 influenza virus isolates identified during the 2011–2012 influenza season were tested against the NAIs oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir for NAI susceptibility using the NA-Fluor, NA-Star, and NA-XTD NI assays. Of the 25 influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 isolates tested, one isolate was resistant to oseltamivir and -peramivir and sensitive to zanamivir in all three NI assays. All of the 82 influenza A (H3N2), 62 influenza B, and the remaining 24 influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 isolates were sensitive to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir in all three NI assays (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of influenza virus isolates (n=169) tested for NAI susceptibility to oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir on three neuraminidase inhibition assays (NA-XTDTM, NA-Star®, and NA-FluorTM): 2011–2012 influenza season, MD DHMH Laboratories

aInfluenza A (H1N1) pdm09 was resistant to oseltamivir and peramivir and sensitive to zanamivir in all three neuraminidase inhibition assays.

NAI = neuraminidase inhibitor

MD DHMH = State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

pdm09 = 2009 pandemic

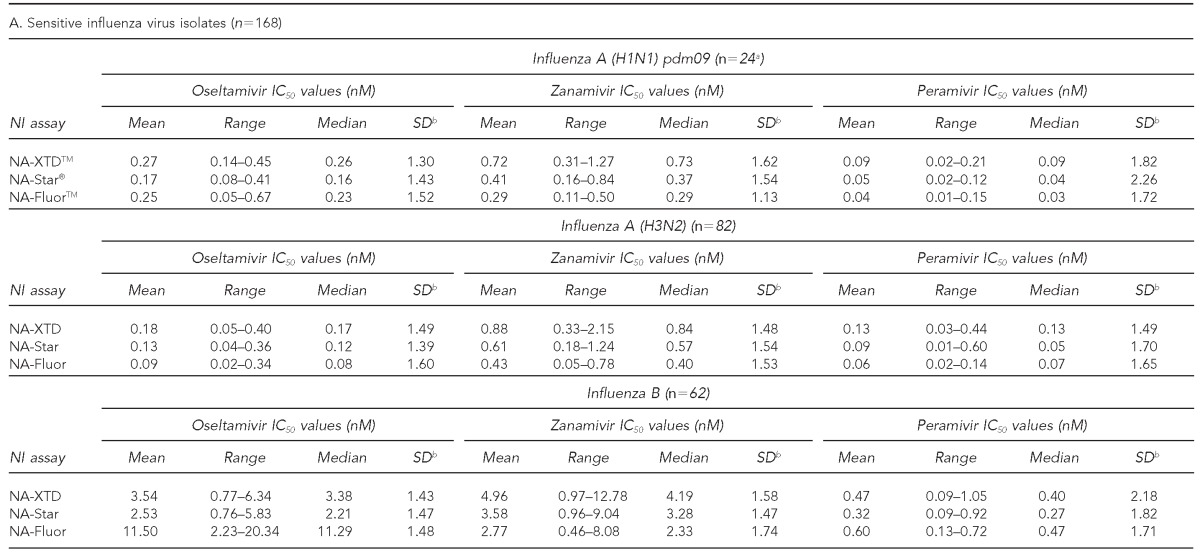

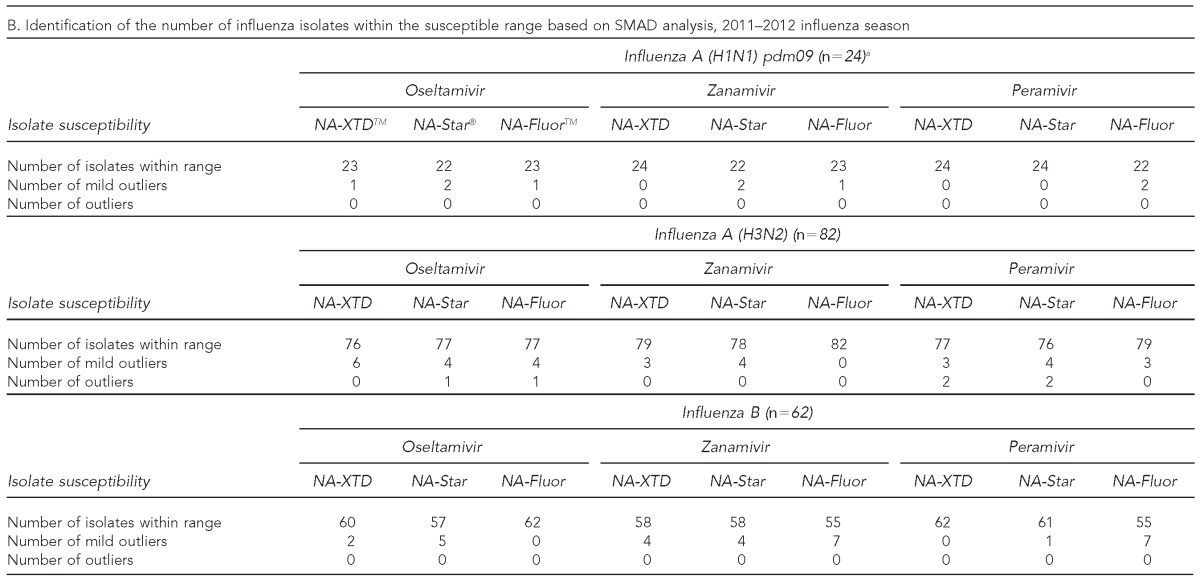

The observed IC50 values of sensitive influenza viruses relative to the three NAIs for each of the NI assays were summarized according to the influenza virus type isolated during the 2011–2012 influenza season in Table 3A. The highest mean and median IC50 values for all strain types across each NI assay were observed with zanamivir followed by oseltamivir, while the lowest mean and median IC50 values were observed with peramivir (Table 3A). Through SMAD analysis, isolates identified as mild outliers (from IC50 median +1.65SD and IC50 median + 3SD) and outliers (≥IC50 median + 3SD) were observed in the dataset and summarized in Table 3B. However, none of the isolates consistently met the key criteria of a mild outlier or an outlier in all three assays for a given NAI. Furthermore, each of these isolates identified as outliers were within threefold of the corresponding wild-type reference viruses.

Table 3.

Characterization of phenotypic susceptibility and IC50 values for influenza virus isolates tested using three commercially available neuraminidase inhibition assays against oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir: 2011–2012 influenza season, MD DHMH Laboratories Administration

aThe IC50 value was excluded for the identified resistant influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 strain.

bRobust estimates of the log-10 transformed SD calculations were performed using SMAD analysis on log10 transformed data, and results presented were back-transformed.

cResistant to oseltamivir and peramivir and sensitive to zanamivir

dFold change refers to the ratio of isolates' observed IC50 value to the observed mean A (H1N1) pdm09 IC50 value.

IC50 = 50% inhibitory concentration

MD DHMH = State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

pdm09 = 2009 pandemic

nM = nanomolar

NI = neuraminidase inhibition

SD = standard deviation

NA = neuraminidase

SMAD = standard deviation based on the median absolute deviation of the median

NAI = neuraminidase inhibitor

One influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus isolated during the 2011–2012 influenza season was determined to be resistant to oseltamivir and peramivir but sensitive to zanamivir based on an IC50 value greater than tenfold higher than the wild-type reference strain. As a result, it was excluded from SMAD analysis. However, resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir was further established in comparison with the mean IC50 values of the other 24 influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 isolates tested. This isolate had an oseltamivir IC50 concentration that was 357-fold greater than the mean in NA-XTD, 561-fold greater than the mean in NA-Star, and 807-fold greater than the mean in NA-Fluor. The IC50 values for peramivir were 124-, 70-, and 438-fold higher than the influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 means for NA-XTD, NA-Star, and NA-Fluor, respectively (Table 3C).

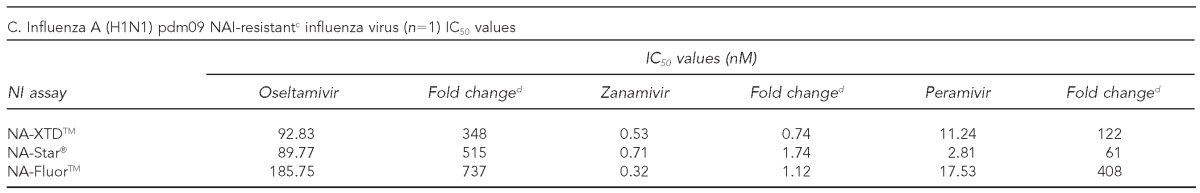

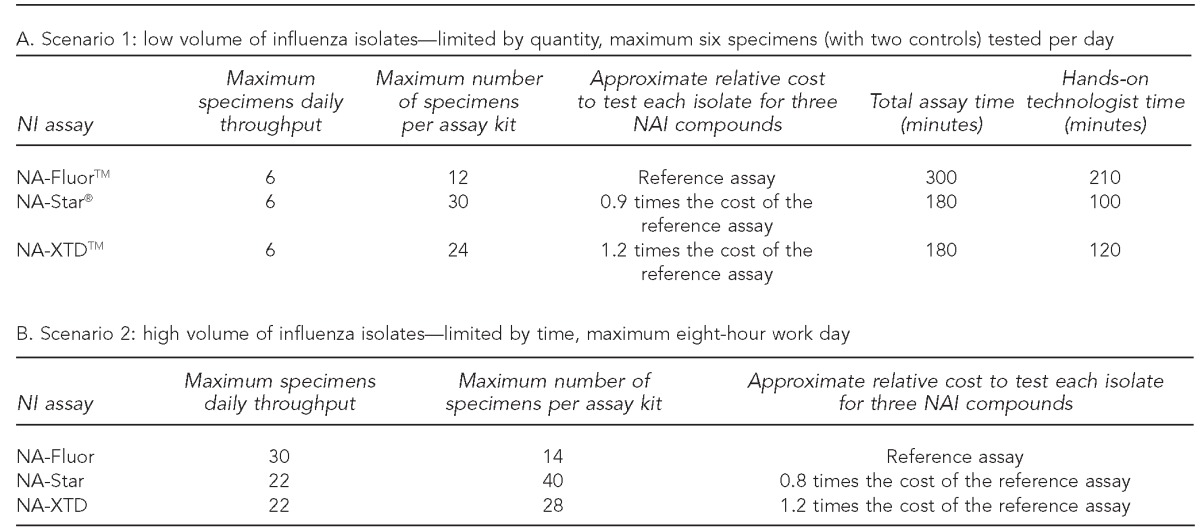

The evaluation of the three commercially available NI assays on parameters of workflow and use of resources were summarized in two testing scenarios with NA-Fluor as the reference assay. In Scenario 1 (Table 4A), the time to prepare reagents, perform the assay, analyze, and interpret the results of six specimens and one sensitive and one resistant reference virus against all three drugs using NA-Star® and NA-XTDTM assays was approximately 180 minutes for each assay, with 100 minutes of hands-on technologist time for NA-Star and 120 minutes of hands-on technologist time for NA-XTD. The NA-Fluor assay was completed in approximately 300 minutes, with 210 minutes of hands-on technologist time. Also, the NA-Fluor assay kit contained reagents to test a maximum of 12 specimens against three NAIs, compared with 30 specimens for the NA-Star assay kit and 24 specimens for the NA-XTD assay kit. The relative cost per specimen for NA-Star was lower than for NA-Fluor, while NA-XTD had a higher relative cost per specimen than NA-Fluor.

Table 4.

Evaluation of three commercially available NI assays using three NAIs for low-volume (Scenario 1) and high-volume (Scenario 2) testing situations: 2011–2012 influenza season, MD DHMH Laboratories Administration

NI = neuraminidase inhibition

NAI = neuraminidase inhibitor

MD DHMH = State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

In Scenario 2 (Table 4B), the highest maximum daily throughput using the NA-Fluor assay was 30 specimens. The NA-XTD and NA-Star assays both had a maximum daily throughput of 22 specimens. The maximum number of specimens tested per assay kit for all three assays was higher in Scenario 2, with 14 specimens for NA-Fluor, 28 specimens for NA-XTD, and 40 specimens for NA-Star. While the overall cost per specimen was lower for each assay compared with Scenario 1, the relative cost remained the same for NA-XTD but decreased for NA-Star compared with the NA-Fluor assay.

DISCUSSION

Our purpose was to evaluate and provide guidance on the use of NI assays in a PHL setting during the influenza season. The aforementioned results represent screening for NAI susceptibility of influenza A and B viruses circulating in Maryland during the 2011–2012 influenza season as identified by the MD DHMH Laboratories Administration. Through the implementation of the three NI assays—NA-Fluor, NA-Star, and NA-XTD enzyme inhibition assays—we have presented multiple references for baseline IC50 values (and, thus, phenotypic characterization) of seasonally circulating influenza viruses in Maryland. Generating these data will further enable the characterization of IC50 values for future influenza seasons to monitor changes in NAI susceptibility over time.

Due to the variability and inherent differences in the chemistry of fluorescent and chemiluminescent assays, the IC50 values for a given isolate have been different for each assay. The MD DHMH Laboratories Administration tested a panel of reference viruses with recognized NA mutations and documented IC50 values provided by CDC to verify each assay. If the decision is made to use a combination of different assays, it is necessary to verify the ability to detect accurately and consistently the susceptibility of a variety of virus strain types to all NAIs for each assay. Verification ensures that the interpretation of the results remains reliable.

We suggest that it may be worth the return on investment to consider implementing fluorescent and chemiluminescent NI assays to accommodate influenza seasonal needs. Improved preparedness may be manifested by an efficient response, with a high throughput assay for high-volume scenarios or a faster turnaround time for low-volume scenarios that may contribute to reducing both economic and personnel resources. Additionally, this strategy provides the ability to compare and better characterize inconclusive results through additional testing. We have indicated the advantages of implementing multiple assays and considered the challenges presented in performing statistical analysis. While the results of the two chemiluminescent assays may be more closely comparable, thus presenting less of a challenge for combined analysis, the established differences in IC50 values between the chemiluminescent and fluorescent assays suggest that they cannot be directly compared. While quantitative differences in the results may not be an issue for gross screening, it may present challenges for deeper analysis.

We recognize that the availability of PHL resources may require using a single NI assay. The use of a single assay involves less time for training and maintaining competencies of the technologists, which may provide logistical and resource benefits. For long-term statistical analysis, the results from a single assay will make it easier to detect a significant elevation in IC50 values.

Due to the innate variability between the NI assays and between day-to-day testing, it is necessary to create several criteria to define reduced susceptibility and to identify isolates that may warrant further investigation. Our results show that, overall, the three assays are comparable in terms of their ability to identify an isolate as “resistant” or “sensitive.” The differences in interpreting NAI susceptibility are most apparent when defining outliers. There was a discrepancy in the interpretation of outliers and minor outliers among assays; however, none of them also met the first criteria for resistance when comparing IC50 values with the reference panel. Although there is little evidence for any immediate implications of outliers and minor outliers, these data may be valuable for future trend analysis of identifying the emergence of novel resistance markers.

Additionally, we have observed that in vitro cross-resistance exists for oseltamivir and peramivir in an influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 strain. Such information continues to be vital to public health treatment decisions, including implications for treatment with the investigational NAIs, such as peramivir, in high-risk patients having influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 infections. Hence, an important aspect of NAI susceptibility testing is to include a broad panel of NAIs. The value of performing NAI susceptibility testing on investigational NAIs may be underscored by the effort and expense involved in developing, testing, and approving new drugs. In the future, it may be beneficial to establish panels to include other investigational NAIs.

Whether or not to screen all the samples is a multifaceted decision that may be based on the PHL's available resources and surveillance needs. In this study, we did not limit the quantity of virus isolates tested. Virus culture was attempted on all available samples. The quantity of viral isolates available for NAI susceptibility testing was generally limited by which samples propagated in cell culture produced sufficient viral titers.

Primarily, our data suggest a general comparability of the NI assays, allowing the PHL to use the most appropriate NI assay regardless of the seasonal burden. These experiences may provide valuable information toward the development of general guidelines for phenotypic drug-resistance testing that consider a PHL's workload and available resources.

Considering Scenario 1, when the number of influenza-positive samples is low and early detection is crucial (Figure 2), total time, sensitivity, and costs are the highest priority. For this reason, NA-Star is highly recommended because it takes less technologist time, costs less per sample than NA-XTD and NA-Fluor, and is more sensitive than NA-Fluor. The higher sensitivity of NA-XTD compared with NA-Star and NA-Fluor may be advantageous for detecting NA activity in virus isolates that have low titers or possible decreased viral fitness resulting from resistance-inducing mutations.17,18 In a situation such as the 2011–2012 influenza season, in which the average number of viruses isolated was fewer than eight per day, NA-Star could be used as the sole NI assay throughout the season (Figure 2). NA-Star is also recommended during the beginning stages of a pandemic, similar to that of the 2009 influenza pandemic, in which it is essential to characterize the phenotypic NAI susceptibility early using a cost-effective, high-sensitivity assay (Figure 2). It is important to note that CDC's guidance must be followed before a PHL can propagate a novel influenza virus in cell culture, which may delay the ability to conduct early, targeted testing in an efficient manner.

Figure 2.

Considerations for the use of three NI assays using the 2009 influenza pandemic and the 2010–2011 and 2011–2012 influenza seasonsa as examples

aAs identified by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction at the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Laboratories Administration Division of Molecular Biology

NI = neuraminidase inhibition

The optimal virus dilution required for the NA-Star assay was comparable with the NA-XTD platform. However, the low stability of the NA-Star substrate signals in each well necessitates reading the plates immediately by a luminometer equipped with an injector. With a substrate incubation period of 30 minutes, there can be a queue of no more than three plates (10 minutes to read each plate). The longer stability of NA-XTD allows more plates to be read, and wait time in the queue can be increased from 30 minutes to two hours without affecting signal strength.

Considering Scenario 2, when the number of influenza-positive virus isolates available for NI assays is in high volume (e.g., at the peak of an influenza season or in the middle of a pandemic) (Figure 2), the limiting factor is considered to be the normal eight-hour workday. NA-Fluor is highly recommended because it has the advantage of maximizing throughput. This higher throughput of NA-Fluor is mainly the result of productivity that occurs during the one-hour incubation period after the addition of the substrate, which provides enough time to set up additional specimens for testing without the overlap of time-sensitive, manually intensive steps. Furthermore, the signal stability improves the workflow to accommodate larger batches of specimens in each set of tests. For each additional set of eight samples tested in a given day, there is a gain of two samples (as only one set of controls is needed per day), which results in a faster turnaround time and larger datasets for timely and robust PHL surveillance. If early resistance to one or more of the NAIs is detected as seen in Scenario 1 by using one of the NI assays, targeted screening of subpopulations with similar subtypes, regional distributions, or from an outbreak cluster may be necessary. Switching to a fluorescent-based assay, such as NA-Fluor, may allow for a relatively cost-effective, high-throughput screening of additional influenza isolates.

Overall, the higher throughput of Scenario 2 offers more cost savings than Scenario 1. The most dramatic increase was seen in the case of NA-Star, where 2 milliliters of NA-Star Accelerator (limiting reagent) were saved per eight samples because there was no need for injector priming, resulting in a total gain of 10 tested samples per assay kit. During periods of high-volume testing and limited available resources, maximizing throughput with NA-Star may offer the most cost-effective method of drug-resistance screening.

CONCLUSION

Our experience suggests a general comparability of the three NI assays, providing the MD DHMH Laboratories Administration guidelines for using the most appropriate NI assay regardless of the seasonal influenza burden. Generating phenotypic NAI susceptibility data for a broad range of type-specific seasonally circulating influenza strains contributes to robust PHL surveillance through monitoring and characterizing baseline IC50 values and identifying future patterns that may indicate clinically relevant changes in NAI susceptibility. While the results show that a majority of all influenza A (H3N2), influenza A (H1N1) pdm09, and influenza B isolates tested were sensitive, they also suggest that resistant influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 viruses do emerge. For each of the three NI assays, we have shown that the same criteria can be used to identify influenza viruses with reduced NAI susceptibility. Lastly, our results contribute valuable information for PHLs toward the development of general guidelines for phenotypic drug-resistance testing that consider a PHL's workload and available resources.

Footnotes

The authors William Murtaugh, Lalla Mahaman, and Benjamin Healey had equal contributions as first authors on this article. The authors thank the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (MD DHMH) Laboratories Administration Division of Molecular Biology, CDC/Association of Public Health Laboratories Emerging Infectious Diseases Fellowship Program, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH) Office of Public Health Practice and Training, and the JHSPH Public Health Applications for Student Experience Program. The findings in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the MD DHMH, CDC, or Johns Hopkins University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Food and Drug Administration (US) Influenza (flu) antiviral drugs and related information. [cited 2012 Jul 16]. Available from: URL: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/informationbydrugclass/ucm100228.htm#ApprovedDrugs.

- 2.GlaxoSmithKline. RelenzaTM: highlights of prescribing information. Research Triangle Park (NC): GlaxoSmithKline; 2011. [cited 2012 May 7]. Also available from: URL: http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_relenza.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roche Laboratories Inc. Tamiflu® (oseltamivir phosphate) capsules and for oral suspension. Nutley (NJ): Roche Laboratories Inc.; 2008. [cited 2012 May 7]. Also available from: URL: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021087s047,%20021246s033lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorbello A, Jones SC, Carter W, Struble K, Boucher R, Truffa M, et al. Emergency use authorization for intravenous peramivir: evaluation of safety in the treatment of hospitalized patients infected with 2009 H1N1 influenza A virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurt AC, Holien JK, Parker MW, Barr IG. Oseltamivir resistance and the H274Y neuraminidase mutation in seasonal, pandemic, and highly pathogenic influenza viruses. Drugs. 2009;69:2523–31. doi: 10.2165/11531450-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorlund K, Awad T, Boivin G, Thabane L. Systematic review of influenza resistance to the neuraminidase inhibitors. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oseltamivir-resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in two summer campers receiving prophylaxis—North Carolina, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(35):969–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Oseltamivir-resistant novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in two immunosuppressed patients—Seattle, Washington, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(32):893–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le QM, Wertheim H, Tran ND, van Doorn HR, Nguyen TH, Horby P. A community cluster of oseltamivir-resistant cases of 2009 H1N1 influenza. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:86–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0910448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen HT, Fry AM, Gubareva LV. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in influenza viruses and laboratory testing methods. Antivir Ther. 2012;17(1 Pt B):159–73. doi: 10.3851/IMP2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Update: influenza activity—United States, 2011–12 season and composition of the 2012–13 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(22):414–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) 2011–2012 flu season draws to a close. [cited 2012 Jun 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/2011-2012-flu-season-wrapup.htm.

- 13.Life Technologies Corporation. Applied Biosystems® NA-Star® influenza neuraminidase inhibitor resistance detection kit protocol. Foster City (CA): Applied Biosystems; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Life Technologies Corporation. Applied Biosystems NA-XTDTM influenza neuraminidase assay kit protocol. Foster City (CA): Life Technologies Corporation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Life Technologies Corp. Applied Biosystems NA-FluorTM influenza neuraminidase assay kit protocol. Foster City (CA): Life Technologies Corporation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wetherall NT, Trivedi T, Zeller J, Hodges-Savola C, McKimm-Breschkin JL, Zambon M, et al. Evaluation of neuraminidase enzyme assays using different substrates to measure susceptibility of influenza virus clinical isolates to neuraminidase inhibitors: report of the Neuraminidase Inhibitor Susceptibility Network. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:742–50. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.742-750.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheu TG, Deyde VM, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Garten RJ, Xu X, Bright RA, et al. Surveillance for neuraminidase inhibitor resistance among human influenza A and B viruses circulating worldwide from 2004 to 2008. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3284–92. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00555-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okomo-Adhiambo M, Sleeman K, Ballenger K, Nguyen HT, Mishin VP, Sheu TG, et al. Neuraminidase inhibitor susceptibility testing in human influenza viruses: a laboratory surveillance perspective. Viruses. 2010;2:2269–89. doi: 10.3390/v2102269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Society for Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses (Isirv) Antiviral Group. Panel of influenza A and B viruses for assessment of neuraminidase inhibitor susceptibility. 2012. [cited 2012 Jun 18]. Available from: URL: http://www.isirv.org/site/images/stories/avg_documents/Resistance/avg%20leaflet%20nov12.pdf.

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) JASPR: Version 1.2. Atlanta: CDC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Society for Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses (Isirv) Antiviral Group. Analysis of IC50 data. [cited 2012 Jun 18]. Available from: URL: http://isirv.org/site/index.php/methodology/analysis-of-ic50-data.