Abstract

The metabolic syndrome is a clustering of cardiovascular risk factors, including insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, and is associated with other comorbidities such as a proinflammatory state and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Its prevalence is high, especially among developed countries, and mainly reflects overnutrition and sedentary lifestyle. Moreover, the developing countries are not spared, as obesity and its related problems such as the metabolic syndrome are increasing quickly. We review the potential primary role of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in the pathophysiology of the metabolic syndrome, showing that in lean, young, insulin-resistant individuals, impaired muscle glucose transport and glycogen synthesis redirect energy derived from carbohydrate into hepatic de novo lipogenesis, promoting the development of atherogenic dyslipidemia and NAFLD. The demonstration of a link between skeletal muscle insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome offers opportunities in targeting early defects in muscle insulin action in order to counteract the development of the disease and its related complications.

Keywords: intramyocellular lipids, muscle glycogen synthesis, hepatic de novo lipogenesis, mitochondrial dysfunction, physical activity

INTRODUCTION

The metabolic syndrome is the close association of several cardiovascular risk factors including insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, hypertension, hyperuricemia, a prothrombotic state, and a proinflammatory state (28). The exact criteria for the metabolic syndrome vary depending on the issuing organization. For example, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) (4) has much lower cutoffs for key measures compared to the World Health Organization (WHO) (5), the European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR) (8), and the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) (1) (Table 1). In contrast, the WHO criteria are the only ones to list microalbuminuria. The IDF has recently joined several other large organizations in issuing a consensus statement in an attempt to unify criteria defining the metabolic syndrome (3). More than 50 million Americans are already classified as having the metabolic syndrome, and about half of all Americans are predisposed to it (35). The metabolic syndrome is also reaching developing countries. Indeed, the WHO estimates that more than 115 million people are suffering from obesity-related problems (53) in the developing world.

Table 1.

Definitions of the metabolic syndrome

| WHO | EGIR | IDF | NCEP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Presence of DM, IFG, IGT, or insulin resistance and two of the following: | Insulin resistance and two of the following: | Central obesity (ethnicity specific) and two of the following: | Three of the following: |

| Anthropometric data | WHR >0.9 (men) or >0.85 (women) and/or BMI >30 kg/m2 | Waist circumference ≥94 cm (men) or 80 cm (women) | Waist circumference >102 cm (men) or 88 cm (women) | |

| Lipids | TG ≥1.7 mmol/l and/or HDL-C <0.9 mmol/l (men) or <1.0 mmol/l (women) | TG ≥2.0 mmol/l and/or HDL-C <1.0 mmol/l | TG ≥1.7 mmol/l and/or HDL-C <1.0 mmol/l (men) or 1.3 mmol/l (women) | TG ≥1.7 mmol/l and/or HDL-C ≤1.03 mmol/l (men) or 1.29 mmol/l (women) |

| Blood pressure | ≥140/90 mm Hg | ≥140/90 mm Hg | ≥130/85 mm Hg | ≥130/85 mm Hg |

| Blood glucose | FPG ≥6.1 mmol/l | FPG ≥5.6 mmol/l or previously diagnosed DM type 2 | FPG ≥6.1 mg/dl | |

| Others | Urinary albumin excretion ratio ≥20 mg/min or albumin:creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g |

BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; EGIR, European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IDF, International Diabetes Federation; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; NCEP, National Cholesterol Education Program; TG, triglycerides; WHO, World Health Organization; WHR, waist-hip ratio.

Abdominal obesity and insulin resistance have both been hypothesized to be the primary factors underlying the metabolic syndrome. However, the exact mechanisms linking these and other risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome are not fully understood. This review of recent findings demonstrates that insulin resistance in skeletal muscle diverts ingested carbohydrate away from muscle glycogen storage into hepatic de novo lipogenesis, secondarily leading to hypertriglyceridemia and decreased plasma high-density lipoprotein concentrations, thus promoting the atherogenic dyslipidemia associated with the metabolic syndrome.

MUSCLE INSULIN RESISTANCE

How Do Healthy Individuals Dispose of Glucose Loads?

Ingested carbohydrates are either oxidized or stored as glycogen in liver and muscles and, to a lesser extent, converted to fat in the liver via de novo lipogenesis. This storage represents nonoxidative glucose disposal. The liver normally contains 75 to 100 g of glycogen but can store up to 120 g, which represents 8% of its weight as glycogen. In comparison, skeletal muscle only stores 1% to 2% of its weight in glycogen. However, because of the greater total mass, skeletal muscle has the largest store of glycogen in the body (300 g to 400 g). Using indirect calorimetry in combination with femoral vein catheterization and the euglycemic-insulin clamp technique, DeFronzo et al. (21) found that nonoxidative glucose metabolism is the major pathway for glucose disposal in healthy subjects when glucose is administered intravenously. Sequential liver and skeletal muscle biopsies performed in healthy individuals under euinsulinemic-hyperglycemic (20 mM) conditions suggested that about 60% of an intravenous infusion of glucose was stored as glycogen (11, 58). Since glycogen can rapidly hydrolyze in biopsy samples, these studies may have underestimated glycogen synthesis. In contrast, muscle glycogen synthesis can be measured noninvasively using 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). Investigators using this approach found that muscle glycogen synthesis accounts for the vast majority of the nonoxidative glucose metabolism in healthy subjects during hyperglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp studies (85).

Oral carbohydrate administration, which represents the most physiological route, was also assessed using similar in vivo 13C MRS methods. Taylor et al. (90) calculated from total muscle mass measurements and estimation of carbohydrate absorption rates that, at peak, muscle glycogen concentrations accounted for about 26% to 35% of the absorbed carbohydrate. Using the same methods, Taylor et al. (89) demonstrated that net hepatic glycogen synthesis was 19% of the carbohydrate content of a mixed meal.

Insulin Signaling and Glucose Uptake in Skeletal Muscle of Healthy Individuals

Insulin stimulates glucose uptake by the cell. Glucose itself is the stimulus for insulin secretion by the β cells in the endocrine pancreas. The signal cascade begins with binding of insulin to the insulin receptor (IR). IR is an α2 β2 heterodimeric transmembrane protein that possesses intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity. Insulin binding to the extracellular domain of the α. subunit induces conformational changes of the receptor, resulting in autophosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domain of the β subunit. This in turn stimulates the catalytic activity of receptor tyrosine kinase and creates recruitment sites for insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1). IRS-1 then activates phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which phosphorylates phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-biphosphate to phosphatidyl inositol 3,4,5-triphosphate, leading to the activation of AKT2 (also known as protein kinase B) as well as the atypical protein kinase C (PKC) isozymes PKCζ and PKCλ. (6). Both AKT2 and the atypical PKCs are involved in the translocation of the glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) from the cytosol to the plasma membrane, which then allows glucose to enter the cell. Glucose is then phosphorylated by the enzyme hexokinase. The resulting glucose-6-phosphate is then either utilized in the glycolytic pathway or incorporated into glycogen by glycogen synthase.

Skeletal Muscle Insulin Resistance and Glucose Metabolism

In type 2 diabetic patients, baseline glycogen concentrations were shown to be ~30% lower than in matched controls (14, 85). Moreover, the rate of glycogen synthesis in skeletal muscle was ~50% lower in type 2 diabetics than in healthy individuals during hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps (85). Post-prandial increments in skeletal muscle glycogen were also significantly lower than those in healthy subjects (14). First-degree relatives of type 2 diabetic patients have a ~40% risk of developing diabetes, and insulin resistance is thought to play an important role in its potential occurrence (47). In these individuals, baseline glycogen concentrations were similar to those of healthy individuals, but insulin-stimulated rates of skeletal muscle glycogen synthesis were reduced by 63% (62).

Type 2 diabetic patients have a blunted increment in intramyocellular glucose-6-phosphate concentrations in comparison with age-weight matched control subjects following a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp (77), which suggests that glucose transport and/or phosphorylation is the rate-controlling step in insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in skeletal muscle. Similar findings were made in lean insulin-resistant offspring of type 2 diabetic patients (76) and nondiabetic obese women (67), which suggests that this defect precedes the development of type 2 diabetes.

To determine whether glucose transport or glucose phosphorylation (through hexokinase) was the rate-controlling step leading to decreased glycogen synthesis in type 2 diabetic patients, Cline et al. (20) used a novel 13C MRS method to measure intracellular free glucose concentrations in muscle during a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp. They found that intracellular glucose concentrations in skeletal muscle of type 2 diabetics were ~4% of what they would have been if hexokinase were the primary rate-controlling enzyme, which suggests that glucose transport was the rate-controlling step for insulin-stimulated skeletal muscle glycogen synthesis in type 2 diabetic patients (20).

Linking Insulin Resistance and Intramyocellular Lipids

Randle et al. (72) first suggested that elevations in plasma fatty acid concentrations would impair insulin-stimulated muscle glucose utilization, primarily by inhibiting glycolysis at several key enzymes. Lipid infusions combined with heparin to activate lipoprotein lipase, acutely increase plasma fatty acid concentrations, and impair both intravenous glucose tolerance (82) and insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in normal humans (12, 26, 69, 74). However, the development of insulin resistance during lipid infusion studies is temporally associated with the accumulation of intramyocellular lipids (7).

Proton (1H) MRS methods have been developed to noninvasively measure hepatic and muscle triglyceride (TG) in humans, which is a clear advantage over invasive biopsies. One challenging problem is to distinguish between intramyocellular lipid and extramyocellular lipid content. This can be accomplished by 1H spectra analysis. 1H peaks correspond to lipids, namely methylene and methyl protons of TG acyl chains within muscle. These peaks are shifted in frequency from each other by 0.2 ppm and represent two distinct compartments, an extramyocellular pool and intramyocellular TG. The 1H MRS technique has been well validated against biochemical TG measurements (34, 88). 1H MRS measurements of intramyocellular lipids in humans correlate even more closely with insulin resistance than do classic anthropometric data such as body mass index (BMI), waist-hip ratio, or total body fat (49). This technique can also be used in dynamic conditions to assess the change in intramyocellular lipids following a specific intervention (42).

Krssak et al. (49) found that in normal healthy, nondiabetic, nonobese subjects, intramyocellular lipids measured by 1H MRS were a good indicator of whole-body insulin sensitivity, the latter assessed by the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp technique. To examine the mechanism by which plasma fatty acids induce insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle, Roden et al. (74) measured glycogen and glucose-6-phosphate, while Dresner et al. (26) also measured intracellular glucose concentrations using 13C and 31P MRS in healthy subjects before and after a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp following a lipid infusion. Rates of insulin-stimulated whole-body glucose uptake, glucose oxidation, and muscle glycogen synthesis were 50% to 60% lower following the lipid infusion and were associated with an approximately 90% decrease in the increment in intramuscular glucose-6-phosphate concentration, implying diminished glucose transport or phosphorylation activity. To distinguish between these two possibilities, intracellular glucose concentration was measured and found to be significantly lower in the lipid infusion studies, implying that glucose transport is the rate-controlling step under these conditions (26). These results shifted the paradigm regarding the mechanism by which fatty acids induce insulin resistance by demonstrating that fatty acids directly impair insulin-stimulated glucose transport activity in contrast to Randle’s prediction of fatty acid-induced inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase and glycolysis (26, 74).

Obesity is clearly associated with skeletal muscle insulin resistance (29). In rodents, the development of skeletal muscle insulin resistance after a few weeks of high-fat diet is associated with the accumulation of TG in skeletal muscle (23, 86).

Although many studies show a correlation between intramyocellular lipids and insulin resistance, there are some exceptions. Endurance-trained athletes have increased intramyocellular lipids while remaining markedly insulin sensitive (70), hence the name athlete paradox. Indeed, elite endurance-trained athletes are among the most insulin-sensitive individuals although their intramyocellular lipid concentration is extremely high (32).

A rodent model of the athlete paradox provides interesting molecular explanations of this phenomenon. Indeed, skeletal muscle-specific transgenic overexpression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1)inmice decreases diacylglycerol (DAG) and ceramide but augments TG synthesis in skeletal muscle, leading to an increase in intramyocellular lipids. However, these mice are protected against fat-induced insulin resistance because of a decrease in DAG and a decrease in the activity of PKCθ (50), confirming a link between DAG, PKC activation, and insulin resistance.

In nonathletes, TG and DAG are also correlated with insulin resistance in most situations, but not all. Therefore, MRS measurement of intramyocellular lipids is a good marker of insulin resistance in sedentary individuals.

Although ectopic lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle and liver is typically observed in most obese individuals, it is also encountered when fat tissue is absent, as in the lipodystro-phies. These conditions may be congenital or acquired and are characterized by partial or complete loss of adipose tissue. Without fat tissue, the low plasma leptin concentrations promote hyperphagia, and without adipose tissue as a suitable storage depot, fat accumulates ectopically (45). In A-ZIP/F-1 (“fatless”) mice, this ectopic lipid deposition could be reversed by transplanting adipose tissue from wild-type mice (30). Moreover, transplantation of wild-type fat reversed the hyperglycemia, dramatically lowered insulin levels, and improved muscle insulin sensitivity (45). It is also interesting to note that humans and mice treated by leptin, an anorexigenic adipokine, had improved insulin-stimulated liver and muscle glucose metabolism as well as decreased hepatic and muscle TG stores (60, 68).

Intramyocellular Lipids and Insulin Resistance: Finding the Culprit

An important but as yet unanswered element linking intramyocellular lipids and insulin resistance is the precise lipid moiety responsible for fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. Although TG accumulation in skeletal muscle (and liver) clearly correlates with insulin resistance, TGs are generally considered metabolically inert associates of more active candidates, including long-chain acylcoenzyme A (LCCoAs), DAG (93), and ceramide (2). These lipid candidates have been evaluated in genetic mouse models with defects at different steps of the lipogenic pathway.

Transgenic mice overexpressing lipoprotein lipase in skeletal muscle were insulin resistant when studied during a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp. These mice had a threefold increase in muscle TG content and were insulin resistant because of decreases in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and insulin activation of IRS-1-associated PI3K activity. These defects in insulin action and signaling were associated with significant increases in intramyocellular lipids, such as LCCoAs, DAG, and ceramide, suggesting a direct and causative relationship between the accumulation of intramyocellular lipid metabolites and insulin resistance (44). Kim et al. (44) found a twofold increase in liver TG content when overexpressing lipoprotein lipase in the liver. These transgenic mice were insulin resistant because of an impaired ability of insulin to suppress endogenous glucose production, which was associated with defects in insulin activation of insulin IRS-2-associated PI3K activity. These defects in insulin action and signaling were associated with increases in intracellular LCCoAs. These data provide a model of hepatic fat accumulation and insulin resistance in the absence of skeletal muscle resistance (44).

DAGs clearly are good candidates to link intramyocellular lipid accumulation and insulin resistance because they activate novel isoforms of PKCs, a family of serine/threonine kinases that has been associated with insulin resistance. In rodents, Griffin et al. (33) showed that lipid infusions lead to the accumulation of intramyocellular DAG and activation of PKCθ.

In rats, Yu et al. (93) demonstrated that insulin resistance following lipid infusions was associated with accumulation of intramyocellular DAG and LCCoAs but without any changes in intramyocellular TG or ceramide, effectively excluding these lipid species as triggers for fat-induced skeletal muscle insulin resistance. An additional clue regarding the specific lipid metabolite that triggers insulin resistance came from mice lacking the mitochondrial isoform of glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (GPAT). GPAT is mostly expressed in liver, and the proportion of this enzyme in skeletal muscle accounts for only a small portion of total GPAT activity. These mice had markedly lower hepatic TG and DAG concentrations in comparison with wild-type mice and were protected from fat-induced hepatic insulin resistance (57) despite an almost twofold increase in LCCoAs, a finding that excludes LCCoAs as mediators of fat-induced insulin resistance.

DGAT exists in two isoforms, DGAT1 and DGAT2 (16, 17). DGAT1 is ubiquitously expressed in human and mouse tissues, with the highest expression levels in the small intestine and white adipose tissue. DGAT2 is primarily expressed in liver and white adipose tissue. As expected, mice lacking DGAT1 displayed reduced liver TG levels, but the concentration of DAG, the substrate of the DGAT reaction, was surprisingly significantly lower in liver and tended to be lower in skeletal muscle (18). These mice were also protected from fat-induced obesity and displayed an increased glucose tolerance. These observations do not support the expectations that based on the function of DGAT1, DAG level would be increased, which would in turn decrease insulin sensitivity. One possible explanation for these findings is that the activity of acyl-CoA:monoacylglycerol acyltransferase is lost, suggesting that DGAT1 also catalyzes this reaction. Thus, loss of DGAT1 may decrease DAG accumulation in skeletal muscle. Intramyocellular lipid concentrations can also be lowered by promoting fatty acid oxidation. One example of this is by genetically modifying carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1. It has been shown that L6E9 muscle cells overexpressing carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 incubated with palmitate were protected against fatty acid-induced insulin resistance by inhibiting both the accumulation of lipid metabolites such as DAG and ceramide and inhibiting the activation of PKCθ and PKCζ (83).

Mice lacking stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD-1) were resistant to diet-induced obesity and showed an increase in glucose tolerance (59) associated with a significant decrease in skeletal muscle TG and ceramide content and (although not measured) presumably because of a decrease in DAG content (24). Also, SCD-1-deficient mice had an increase in insulin-signaling components in muscle (71). Conversely, elevated SCD-1 expression in human skeletal muscle contributed to abnormal lipid metabolism and progression of obesity (39).

Uncoupling proteins are inner mitochondrial membrane transporters that dissipate the mitochondrial proton gradient, thus uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation. Overexpression of uncoupling protein 3 in skeletal muscle protected mice from insulin resistance when fed a high-fat diet. This was associated with a decrease in muscle DAG and an increase in LCCoAs and ceramide, without change in muscle TG. This decrease in DAG was subsequently associated with a decrease in PKCθ activation (19). This study demonstrates that LCCoAs, ceramide, and triglyceride are not the triggers for fat-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle in this mouse model.

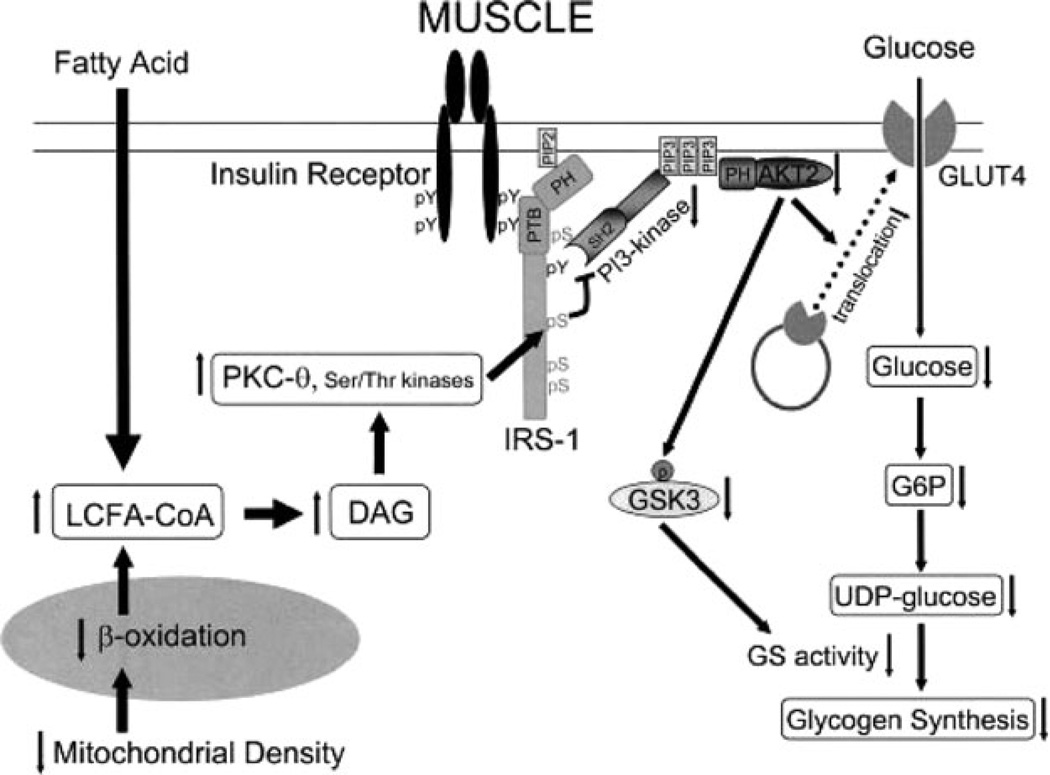

In summary, the accumulation of DAG, but not LCCoAs, TG, or ceramide, provides a unifying explanation for the development of muscle (and liver) insulin resistance (81, 84). This accumulation of intramyocellular lipids results from an imbalance between fatty acid delivery and/or decreased mitochondrial/peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation and/or storage as triglyceride, triggering a serine/threonine kinase cascade initiated by novel PKCs. This results in serine/threonine phosphorylation of critical IRS-1 sites in muscle, thereby inhibiting IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of PI3K, leading to reduced insulin-stimulated muscle glucose transport (mediated by GLUT4) and subsequent reduction in muscle glycogen synthesis (56, 81). The role of the different novel PKC isoforms in fat-induced insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle remains to be further evaluated. The molecular mechanisms of lipid-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Molecular mechanisms of skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Increases in intramyocellular fatty acyl CoAs and diacylglycerol due to increased delivery from plasma and/or reduced oxidation due to mitochondrial dysfunction trigger a serine/threonine kinases cascade initiated by novel protein kinase C. This ultimately leads to activation of serine residues on IRS-1 and inhibits insulin-induced PI3-kinase activity, resulting in reduced insulin-stimulated muscle glucose transport and reduced muscle glycogen synthesis. DAG, diacylglycerol; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase-3; PH, pleckstrin homology domain; PI3, phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase; PTB, phosphotyrosine binding domain. Copyright 2006 American Diabetes Association. From Reference 56, with permission from The American Diabetes Association.

Linking Skeletal Muscle Insulin Resistance and the Metabolic Syndrome

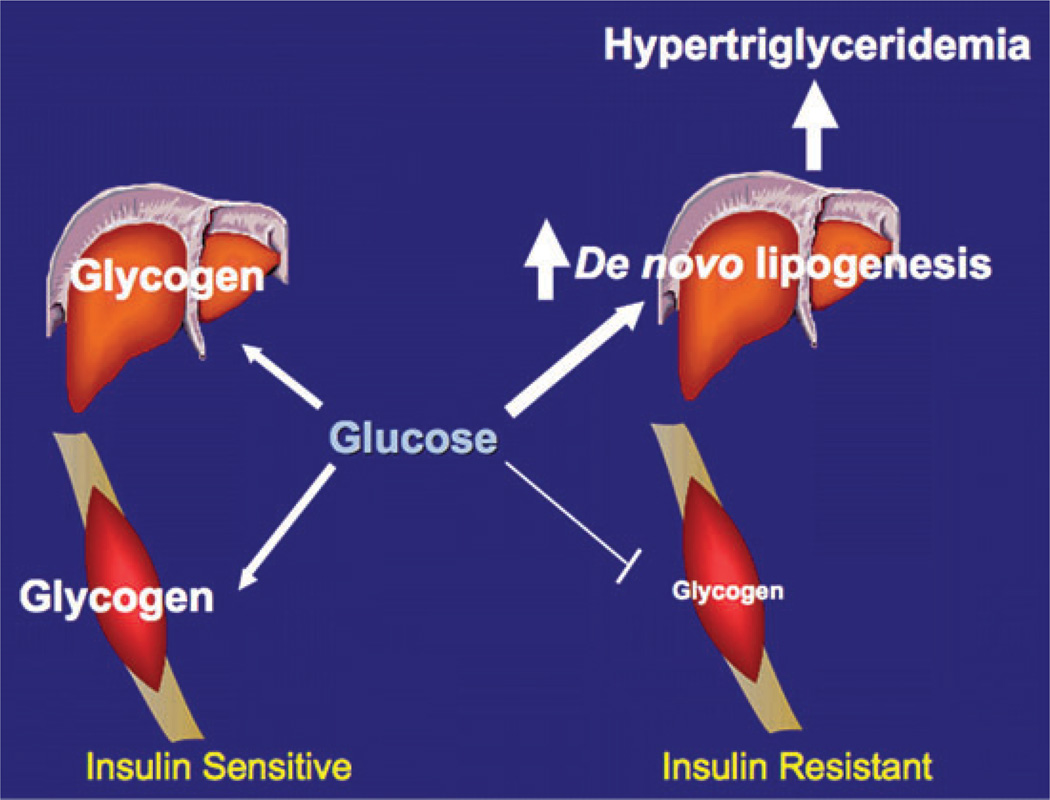

Can skeletal muscle insulin resistance promote the development of atherogenic dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) associated with the metabolic syndrome? Petersen et al. (66) hypothesized that insulin resistance in skeletal muscle decreases nonoxidative storage of ingested carbohydrates, which are then diverted to become substrates for hepatic de novo lipogenesis, resulting in hypertriglyceridemia and reduction in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol concentrations. To address this hypothesis, liver and muscle TG synthesis were assessed by 1H MRS, and liver and muscle glycogen synthesis were assessed by 13C MRS, after the ingestion of two high-carbohydrate mixed meals in young, lean, healthy, insulin-resistant subjects and compared to a group of insulin-sensitive subjects matched for age, weight, body mass index, and activity. Hepatic de novo lipogenesis was assessed at the same time by measuring the incorporation of deuterium from deuteriumlabeled water into plasma triglycerides (22).

The role of skeletal muscle resistance in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome could thus be examined at its earliest stages. After screening 400 subjects at respectively lowest and highest quartile of insulin sensitivity, 12 insulin-resistant and 12 insulin-sensitive individuals were identified. Importantly, great care was taken in closely matching these two groups, not only for age and body mass index, but also for lean body mass, fat mass, monitored physical activity, and blood pressure.

After the two high-carbohydrate mixed meals, postprandial plasma glucose concentrations were similar in the two groups, but postprandial plasma insulin was markedly increased in the insulin-resistant subjects.

Net muscle glycogen synthesis was approximately 60% lower in the insulin-resistant subjects after the mixed meals. Net hepatic TG synthesis was about 2.5-fold greater in the insulin-resistant subjects than the insulin-sensitive subjects after the high-carbohydrate mixed meals. Finally, postprandial fractional hepatic de novo lipogenesis, assessed by the incorporation of deuterated water into plasma TG, was increased by 2.2-fold in the insulin-resistant subjects compared to the insulin-sensitive subjects, with a high level of significance.

This increase in hepatic de novo lipogenesis was associated with an 80% increase in fasting plasma TG concentrations and a 20% reduction in plasma HDL concentrations as well as increased postprandial plasma triglyceride concentrations in the insulin-resistant subjects.

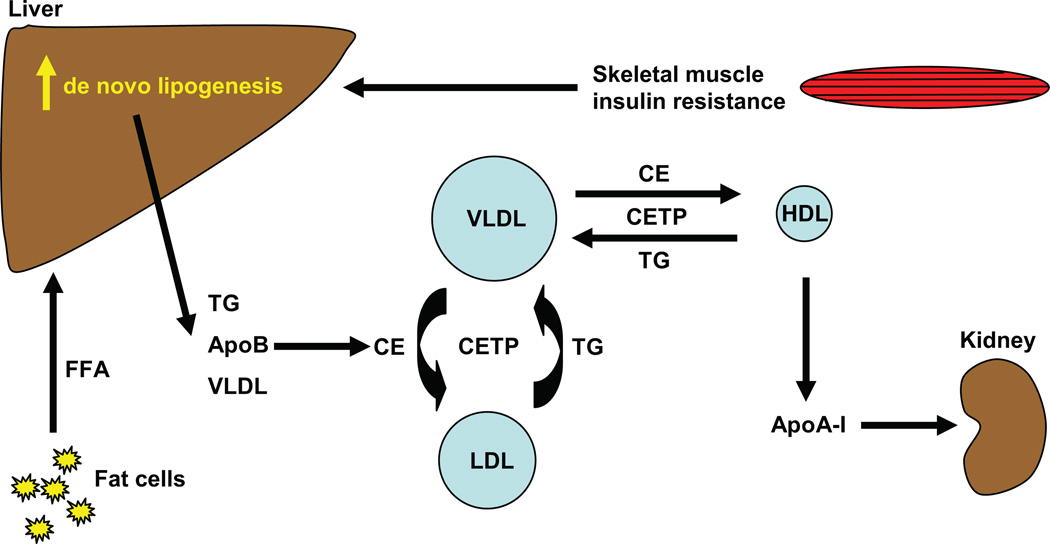

Thus, this young, lean group of insulin-resistant subjects, representing 25% of the population, already had the underpinnings for developing atherogenic dyslipidemia, i.e., increased plasma TG and lower plasma HDL, both associated with the metabolic syndrome. The lower level of plasma HDL in the insulin-resistant subjects could be explained by the following mechanism: Very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) TG can be exchanged for HDL cholesterol in the presence of increased plasma VLDL concentrations and normal activity of cholesteryl ester transfer protein, where a VLDL particle donates a molecule of TG to an HDL particle in return for one of the cholesteryl ester molecules from HDL. This process leads to a cholesterol-rich VLDL remnant particle that is atherogenic and a TG-rich, cholesterol-depleted HDL particle (48). The TG-rich HDL particle can undergo further modification, including hydrolysis of its TG, leading to dissociation of the apoA-1 protein. The free apoA-1 is cleared more rapidly in plasma than the apoA-1 bound to HDL particles, resulting in reduced circulating apoA-1, HDL cholesterol, and the number of HDL particles (31). These modifications in cholesterol metabolism induced by hepatic de novo lipogenesis are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Cholesterol metabolism induced by hepatic de novo lipogenesis. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance increases hepatic de novo lipogenesis, which leads to increased hepatic triglycerides (TGs). TGs can be exchanged for high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol in the presence of increased plasma very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) concentrations and normal activity of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), where a VLDL particle donates a molecule of TG to an HDL particle in return for one of the cholesteryl ester (CE) molecules from HDL. The TG-rich HDL particle can be hydrolyzed of its TG, leading to dissociation of the apolipoprotein A-1 (apoA-1) protein. The free apoA-1 is cleared more rapidly in plasma than the apoA-1 bound to HDL particles, resulting in reduced circulating apoA-1, HDL cholesterol, and the number of HDL particles. FFA, free fatty acid.

Additionally, in this study (66), plasma adipokines, namely adiponectin, interleukin-6, resistin, retinol binding protein-4, and tumor necrosis factor α, were similar between the two groups. The fact that plasma adipokines were similar between the two groups in this study (66) suggests that adipokines are not responsible for causing the insulin resistance in these individuals.

This study also demonstrates that skeletal muscle insulin resistance can precede hepatic insulin resistance and that hepatic TG synthesis is increased after carbohydrate meals via de novo lipogenesis in insulin-resistant subjects, putting them at risk of developing NAFLD later in life. This hypothesis is supported by gene knockout mice studies where mice with muscle-specific insulin receptor inactivation were found to have increased plasma TG concentrations and increased obesity as a result of specific skeletal muscle insulin resistance (46).

ETHNIC DIFFERENCES IN THE PREVALENCE OF NONALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER DISEASE

Of importance, there are likely important ethnic differences in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Notably, Asian Indian males have a marked increase in the prevalence of hepatic steatosis, which is associated with marked insulin resistance (64), despite having a normal BMI. Also, genetic susceptibility exists regarding the development of NAFLD. Indeed, an allele of the enzyme patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3, which is encoded by the PNPLA3 gene, is strongly associated with NAFLD. This variant allele is mostly found in Hispanics but also in some African American and European American individuals (75). This variant is not associated with insulin resistance, suggesting that these carriers present a disassociation between NAFLD and insulin resistance (43). This leads to the hypothesis that hepatic DAG content may be decreased in these individuals.

Very recently, Petersen et al. (65) showed that carriers of ApoC3 polymorphisms (T482/C455) are at risk of developing NAFLD and insulin resistance. Therefore, this study demonstrates an important role of genetic susceptibility in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and insulin resistance. Furthermore, they found that the NAFLD and insulin resistance were reversed with modest weight reduction. Taken together, these data suggest a geneenvironment interaction in which carriers of the ApoC3 gene variants (T482/C455) are predisposed to NAFLD and insulin resistance at a lower BMI than that of noncarriers.

For most populations, NAFLD is strongly linked to hepatic insulin resistance and is a risk for the development of impaired fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes (57, 78, 80). Liver TG can arise from re-esterification of fatty acids released from adipose tissue or absorbed after a meal or from de novo lipogenesis. Donnelly et al. (25) measured the relative contributions of these pathways in subjects with NAFLD. Though re-esterification of TG released from adipose accounted for the largest portion of liver TG synthesis, the most striking finding was the increase in de novo lipogenesis in patients with NAFLD. They found that de novo lipogenesis accounted for 26% of liver TG. Moreover, they found that in patients with NAFLD, de novo lipogenesis was consistently elevated, without the normal rise and fall seen under fed and fasted conditions in control subjects (36). Taken together, these data suggest that the insulin resistance increases de novo lipogenesis both prior to and after the development of NAFLD.

ROLE OF VISCERAL FAT IN CAUSING INSULIN RESISTANCE

Visceral obesity is thought to play a role in causing the metabolic syndrome (15). Indeed, insulin-resistant individuals may be predisposed to abdominal (visceral) obesity because of an increased export of TG from the liver to the peripheral adipose tissue in the form of VLDL (27). However, the atherogenic dyslipidemia seen in the study by Petersen et al. (66) happened in the absence of other variables that have been associated with the metabolic syndrome. First, intraabdominal fat content, assessed by magnetic resonance imaging (67), was also similar between the two groups. Although this has been thought to have a role in the development of the metabolic syndrome (15), here the feature of the metabolic syndrome developed without it. These findings suggests that abdominal obesity likely develops later in the course of the metabolic syndrome, along with NAFLD, and that it is a consequence (and a marker) for hepatic steatosis rather than a cause of skeletal muscle insulin resistance, at least in this subset of subjects, i.e., in young, lean, insulin-resistant individuals (66). This hypothesis is supported by the previously discussed studies of lipodystrophic humans (68) and lipodystrophic mouse models (45) that have disassociated intraabdominal adiposity from insulin resistance and instead have implicated hepatic steatosis in causing the hepatic insulin resistance associated with the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes (79).

In summary, the study detailed above (66) supports the hypothesis that skeletal muscle insulin resistance, due to decreased muscle glycogen synthesis, promotes atherogenic dyslipidemia by diverting energy derived from ingested carbohydrates away from muscle glycogen synthesis and into increased hepatic de novo lipogenesis. The mechanism for this increased de novo lipogenesis may result from upregulation of sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), a master transcriptional regulator of lipogenic enzymes activated by portal vein hyperinsulinemia through the nuclear liver X receptor (38). Indeed, insulin increases transcription, posttranslational processing, and nuclear translocation of SREBP-1c.

These observations provide important information regarding the mechanisms linking skeletal muscle insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome as well as NAFLD, type 2 diabetes, and the associated cardiovascular disease. These data also suggest that reversing defects in insulin-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle to reverse insulin resistance in this organ might be the best way to prevent the development of the atherogenic dyslipidemia associated with the metabolic syndrome. The fate of ingested carbohydrates in insulin-resistant and insulin-sensitive subjects is summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Fate of ingested carbohydrates in insulin-resistant and insulin-sensitive subjects. Copyright 2007 from Reference 66, National Academy of Sciences, USA.

MITOCHONDRIAL DYSFUNCTION AND SKELETAL MUSCLE INSULIN RESISTANCE

Recent findings suggest impaired mitochondrial oxidative metabolism as a potential mechanism linking intramyocellular lipids with impaired glucose metabolism and insulin signaling observed in insulin-resistant subjects. The mitochondrion is the major site of fuel oxidation. Mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate production in skeletal muscle was found to be decreased by approximately 30% in a cohort of healthy, lean, insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes (63). In this study, the insulin-stimulated rate of glucose uptake by muscle was approximately 60% lower in the insulin-resistant subjects compared to matched insulin-sensitive subjects and was associated with an increase of approximately 80% in the intramyocellular lipid content. These observations suggest that the decline in mitochondrial function may predispose to muscle lipid accumulation. In a subsequent study, muscle mitochondrial density was 38% lower in a similar cohort of young, lean, normoglycemic, insulin-resistant offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes (55), and these changes were associated with a 50% increase in IRS-1 Ser312 and IRS-1 Ser636 phosphorylation and an approximately 60% reduction in insulin-stimulated AKT2 activation. The expression of cytochrome c oxidase I, which is encoded by the mitochondrial genome, was decreased by 50% in the insulin-resistant subjects. In the same study (55), several key regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis were assessed by skeletal muscle biopsies. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1α) and 1beta (PGC-1β), among many other factors, are transcriptional cofactors that regulate mitochondrial biogenesis, the expression of which has been shown to be reduced in skeletal muscle of type 2 diabetic patients (54) and overweight nondiabetic subjects with a history of diabetes (61). However, the expression of PGC-1α and PGC-1β was similar between insulin-resistant offspring and insulin-sensitive subjects. Therefore, other factors may be responsible for the decreased mitochondrial content in the insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that reductions in mitochondrial content are responsible, at least in part, for the reduced mitochondrial activity that has previously been described in the insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. These changes are independent of alterations in the expression levels of PGC-1α and PGC-1β as well as other factors involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, such as nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (NRF-1 and NRF-2), suggesting that other factors that are as yet unknown are responsible for the reduced mitochondrial content in these insulin-resistant individuals. Whether the reductions in mitochondrial function are primary or secondary in nature is currently not known and remains a critical question that needs to be addressed in future studies. However, given the key role of DAGs in mediating insulin resistance and the strong genetic evidence demonstrating that alterations in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation can alter intracellular DAG content and insulin resistance, these reductions in mitochondrial activity represent an important contributing factor to insulin resistance.

REVERSIBILITY OF SKELETAL MUSCLE INSULIN RESISTANCE

Numerous factors have been related to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, including age, obesity, distribution of skeletal muscle fiber type, and physical activity. Modulation of these factors can also influence mitochondrial function.

Physical activity has been shown to positively influence type 2 diabetes by increasing insulin sensitivity and inducing weight loss. Perseghin et al. (62) showed that six weeks of exercise increased insulin sensitivity in both normal subjects and insulin-resistant offspring of type 2 diabetic parents because of a twofold increase in insulin-stimulated muscle glycogen synthesis. This was due to an increase in insulin-stimulated glucose transport and phosphorylation. A further study reported that muscular adaptations in relation to increased physical fitness include an increased muscle and lipid oxidative capacity mainly caused by an increased mitochondrial volume (37). It has also been demonstrated that a combined intervention of physical activity and weight loss improves insulin sensitivity and increases mitochondrial content (92), but the latter seems to be mainly attributed to an increase in physical activity because weight loss alone does not increase mitochondrial content (91). More recently, Befroy et al. (9) demonstrated that basal mitochondrial substrate oxidation is increased in the muscle of endurance-trained individuals although energy production is unaltered, leading to an uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation at rest. Therefore, increased mitochondrial uncoupling may represent another mechanism by which exercise training enhances muscle insulin sensitivity via increased fatty acid oxidation and intracellular energy dissipation, resulting in decreased intramyocellular DAG content in the resting state (9).

Recent studies suggest that pharmacological treatment may be added to physical activity and weight loss to achieve the goals of normal mitochondrial function and insulin sensitivity. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a major regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis that regulates intracellular energy metabolism in response to acute energy crises. β-guanadinopropionic acid (β-GPA) is a creatine analog acting as a chronic pharmacological activator of AMPK, thus mimicking exercise training and leading to reductions in the intramuscular adenosine triphosphate/adenosine monophosphate ratio as well as phosphocreatine concentrations, subsequently activating skeletal muscle AMPK. Rats fed with β-GPA in their chow for eight weeks had chronic skeletal muscle AMPK activation, resulting in increases in mitochondrial content, thus demonstrating that AMPK activation promotes mitochondrial biogenesis (10). Recently, Reznick et al. (73) examined AMPK activity in young and old rats and found that the acute stimulation of AMPK-α2 activity by the AMPK agonist 5′-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside and exercise was blunted in the skeletal muscle of old rats. Furthermore, mitochondrial biogenesis was diminished in these old rats after the chronic activation of AMPK with β-GPA (73). These findings suggest that AMPK activity is reduced with aging and that it may be an important contributing factor in mitochondrial dysfunction and dysregulated intramyocellular lipid metabolism.

Thiazolidinediones such as pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists frequently used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Troglitazone is another of these molecules, now withdrawn from the market owing to reported issues related to hepatic failure. Troglitazone was shown to decrease fasting and postprandial glucose levels in patients with type 2 diabetes by decreasing basal hepatic glucose production and increasing insulin-stimulated glucose disposal (51). A further study in type 2 diabetic patients revealed that troglitazone mostly acts through an estimated 54% increase in the rate of peripheral glucose disposal (41). Pioglitazone has been shown to induce mitochondrial biogenesis by the activation of the PCG-1α pathway in human subcutaneous adipose tissue (13). Rosiglitazone treatment for eight weeks also increased the expression of PCG-1α and the activity of oxidative enzymes in the skeletal muscle of patients with type 2 diabetes (52). Finally, in A-ZIP/F-1 (“fatless”) mice, three weeks of rosiglitazone treatment normalized the decrease in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and IRS-1 associated PI3K activity in skeletal muscle. These findings suggested that rosiglitazone treatment enhanced insulin action in skeletal muscle by its ability to divert fat away from skeletal muscle (45). Similarly, Mayerson et al. (51a) showed that three months of rosiglitazone treatment improves insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetics by redistributing fat from liver into adipocytes. Metformin, another frequently used drug in the treatment of type 2 diabetes, has also been shown to increase skeletal muscle content of PCG-1α in rats, which suggests increased mitochondrial biogenesis (87). These effects seem to be mediated, at least in part, by an increase in AMPK phosphorylation. In patients with type 2 diabetes, metformin has been shown to act primarily by decreasing endogenous glucose production via inhibition of gluconeogenesis (40, 41).

CONCLUSION

The metabolic syndrome is increasing at a high rate worldwide and is clearly associated with an increased cardiovascular risk. Although its pathophysiological mechanisms remain unclear, recent studies point to a central role of skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Indeed, studies in young, lean, insulin-resistant subjects suggest that a defect in mitochondrial function promotes muscle DAG accumulation activation of PKCθ with downstream impaired insulin signaling. As a result, following a carbohydrate meal, there is a decrease in muscle glucose uptake and muscle glycogen synthesis. Instead, carbohydrate becomes a substrate for hepatic de novo lipogenesis. This in turn increases plasma TG concentration and is associated with a reduction in plasma HDL concentration, contributing to the atherogenic dyslipidemia. Intraabdominal obesity and adipose tissue inflammation, the latter leading to alterations in adipokines concentrations, do not seem to play a primary role in causing insulin resistance in the early stages of the metabolic syndrome and likely play a contributing role later in the course of the disease.

Taken together, these findings suggest that targeting defects in insulin-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle to reverse insulin resistance in this organ might be a promising way to prevent the development of the atherogenic dyslipidemia and NAFLD associated with the metabolic syndrome at its earliest stages.

SUMMARY POINTS.

The metabolic syndrome is a clustering of components reflecting overnutrition and sedentary lifestyle that lead to increased cardiovascular risk.

Skeletal muscle insulin resistance may play a central role in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome.

Studies in young, lean, insulin-resistant subjects suggest that this skeletal insulin resistance is due to decreased muscle glycogen synthesis, resulting in the diversion of ingested carbohydrates away from muscle glycogen synthesis and to hepatic de novo lipogenesis.

These findings provide important implications for understanding not only the pathophysiology of the metabolic syndrome, but also that of NAFLD, type 2 diabetes, and the associated cardiovascular disease.

Reversing skeletal muscle insulin resistance might be the best way to prevent the development of the atherogenic dyslipidemia and NAFLD associated with the metabolic syndrome at its earliest stages.

FUTURE ISSUES.

Further research is needed on:

Identifying the causes of defects in mitochondrial biogenesis and defining the role of heredity in this process.

Defining new pharmacological targets aimed at improving skeletal muscle glucose uptake.

Understanding the genetic factors that predispose individuals to muscle and liver insulin resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work by the authors was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants R01 DK-49230 (GIS), R01 DK-40936 (GIS), and U24 DK-076169 (GIS, VTS) and a VA Merit Award (VTS).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams JM, 2nd, Pratipanawatr T, Berria R, Wang E, DeFronzo RA, et al. Ceramide content is increased in skeletal muscle from obese insulin-resistant humans. Diabetes. 2004;53:25–31. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome—a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005;366:1059–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1:diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet. Med. 1998;15:539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alessi DR, Cohen P. Mechanism of activation and function of protein kinase B. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1998;8:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachmann OP, Dahl DB, Brechtel K, Machann J, Haap M, et al. Effects of intravenous and dietary lipid challenge on intramyocellular lipid content and the relation with insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes. 2001;50:2579–2584. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balkau B, Charles MA. Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR) Diabet. Med. 1999;16:442–443. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Befroy DE, Petersen KF, Dufour S, Mason GF, Rothman DL, Shulman GI. Increased substrate oxidation and mitochondrial uncoupling in skeletal muscle of endurance-trained individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:16701–16706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808889105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergeron R, Ren JM, Cadman KS, Moore IK, Perret P, et al. Chronic activation of AMP kinase results in NRF-1 activation and mitochondrial biogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;281:E1340–E1346. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.6.E1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergstrom J, Hultman E. Synthesis of muscle glycogen in man after glucose and fructose infusion. Acta Med. Scand. 1967;182:93–107. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1967.tb11503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boden G, Lebed B, Schatz M, Homko C, Lemieux S. Effects of acute changes of plasma free fatty acids on intramyocellular fat content and insulin resistance in healthy subjects. Diabetes. 2001;50:1612–1617. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.7.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogacka I, Xie H, Bray GA, Smith SR. Pioglitazone induces mitochondrial biogenesis in human subcutaneous adipose tissue in vivo. Diabetes. 2005;54:1392–1399. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey PE, Halliday J, Snaar JE, Morris PG, Taylor R. Direct assessment of muscle glycogen storage after mixed meals in normal and type 2 diabetic subjects. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;284:E688–E694. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00471.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL, Kodama K, Retzlaff BM, et al. Intra-abdominal fat is a major determinant of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria for the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2004;53:2087–2094. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cases S, Smith SJ, Zheng YW, Myers HM, Lear SR, et al. Identification of a gene encoding an acyl CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase, a key enzyme in triacylglycerol synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:13018–13023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cases S, Stone SJ, Zhou P, Yen E, Tow B, et al. Cloning of DGAT2, a second mammalian diacylglycerol acyltransferase, and related family members. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:38870–38876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen HC, Smith SJ, Ladha Z, Jensen DR, Ferreira LD, et al. Increased insulin and leptin sensitivity in mice lacking acyl CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:1049–1055. doi: 10.1172/JCI14672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi CS, Fillmore JJ, Kim JK, Liu ZX, Kim S, et al. Overexpression of uncoupling protein 3 in skeletal muscle protects against fat-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1995–2003. doi: 10.1172/JCI13579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cline GW, Petersen KF, Krssak M, Shen J, Hundal RS, et al. Impaired glucose transport as a cause of decreased insulin-stimulated muscle glycogen synthesis in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:240–246. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeFronzo RA, Jacot E, Jequier E, Maeder E, Wahren J, Felber JP. The effect of insulin on the disposal of intravenous glucose. Results from indirect calorimetry and hepatic and femoral venous catheterization. Diabetes. 1981;30:1000–1007. doi: 10.2337/diab.30.12.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diraison F, Pachiaudi C, Beylot M. Measuring lipogenesis and cholesterol synthesis in humans with deuterated water: use of simple gas chromatographic/mass spectrometric techniques. J. Mass Spectrom. 1997;32:81–86. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199701)32:1<81::AID-JMS454>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobbins RL, Szczepaniak LS, Bentley B, Esser V, Myhill J, McGarry JD. Prolonged inhibition of muscle carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 promotes intramyocellular lipid accumulation and insulin resistance in rats. Diabetes. 2001;50:123–130. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobrzyn A, Dobrzyn P, Lee SH, Miyazaki M, Cohen P, et al. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 deficiency reduces ceramide synthesis by downregulating serine palmitoyltransferase and increasing beta-oxidation in skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;288:E599–E607. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00439.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donnelly KL, Smith CI, Schwarzenberg SJ, Jessurun J, Boldt MD, Parks EJ. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1343–1351. doi: 10.1172/JCI23621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dresner A, Laurent D, Marcucci M, Griffin ME, Dufour S, et al. Effects of free fatty acids on glucose transport and IRS-1-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:253–259. doi: 10.1172/JCI5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eckel RH, Hernandez TL, Bell ML, Weil KM, Shepard TY, et al. Carbohydrate balance predicts weight and fat gain in adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;83:803–808. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ford ES. Risks for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes associated with the metabolic syndrome: a summary of the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1769–1778. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furler SM, Poynten AM, Kriketos AD, Lowy AJ, Ellis BA, et al. Independent influences of central fat and skeletal muscle lipids on insulin sensitivity. Obes. Res. 2001;9:535–543. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gavrilova O, Marcus-Samuels B, Graham D, Kim JK, Shulman GI, et al. Surgical implantation of adipose tissue reverses diabetes in lipoatrophic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:271–278. doi: 10.1172/JCI7901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginsberg HN. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:453–458. doi: 10.1172/JCI10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodpaster BH, He J, Watkins S, Kelley DE. Skeletal muscle lipid content and insulin resistance: evidence for a paradox in endurance-trained athletes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:5755–5761. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffin ME, Marcucci MJ, Cline GW, Bell K, Barucci N, et al. Free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance is associated with activation of protein kinase C theta and alterations in the insulin signaling cascade. Diabetes. 1999;48:1270–1274. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.6.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruetter R. Automatic, localized in vivo adjustment of all first- and second-order shim coils. Magn. Reson. Med. 1993;29:804–811. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hellerstein MK, Christiansen M, Kaempfer S, Kletke C, Wu K, et al. Measurement of de novo hepatic lipogenesis in humans using stable isotopes. J. Clin. Invest. 1991;87:1841–1852. doi: 10.1172/JCI115206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hood DA, Irrcher I, Ljubicic V, Joseph AM. Coordination of metabolic plasticity in skeletal muscle. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;209:2265–2275. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hulver MW, Berggren JR, Carper MJ, Miyazaki M, Ntambi JM, et al. Elevated stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 expression in skeletal muscle contributes to abnormal fatty acid partitioning in obese humans. Cell Metab. 2005;2:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hundal RS, Krssak M, Dufour S, Laurent D, Lebon V, et al. Mechanism by which metformin reduces glucose production in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2000;49:2063–2069. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inzucchi SE, Maggs DG, Spollett GR, Page SL, Rife FS, et al. Efficacy and metabolic effects of metformin and troglitazone in type II diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;338:867–872. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jucker BM, Schaeffer TR, Haimbach RE, Mayer ME, Ohlstein DH, et al. Reduction of intramyocellular lipid following short-term rosiglitazone treatment in Zucker fatty rats: an in vivo nuclear magnetic resonance study. Metabolism. 2003;52:218–225. doi: 10.1053/meta.2003.50040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kantartzis K, Peter A, Machicao F, Machann J, Wagner S, et al. Dissociation between fatty liver and insulin resistance in humans carrying a variant of the patatin-like phospholipase 3 gene. Diabetes. 2009;58:2616–2623. doi: 10.2337/db09-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim JK, Fillmore JJ, Chen Y, Yu C, Moore IK, et al. Tissue-specific overexpression of lipoprotein lipase causes tissue-specific insulin resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7522–7527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121164498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JK, Gavrilova O, Chen Y, Reitman ML, Shulman GI. Mechanism of insulin resistance in A-ZIP/F-1 fatless mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:8456–8460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim JK, Michael MD, Previs SF, Peroni OD, Mauvais-Jarvis F, et al. Redistribution of substrates to adipose tissue promotes obesity in mice with selective insulin resistance in muscle. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:1791–1797. doi: 10.1172/JCI8305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobberling J. Studies on the genetic heterogeneity of diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1971;7:46–49. doi: 10.1007/BF02346253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krauss RM, Siri PW. Metabolic abnormalities: triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2004;33:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krssak M, Falk Petersen K, Dresner A, DiPietro L, Vogel SM, et al. Intramyocellular lipid concentrations are correlated with insulin sensitivity in humans: a 1H NMR spectroscopy study. Diabetologia. 1999;42:113–116. doi: 10.1007/s001250051123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu L, Zhang Y, Chen N, Shi X, Tsang B, Yu YH. Upregulation of myocellular DGAT1 augments triglyceride synthesis in skeletal muscle and protects against fat-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1679–1689. doi: 10.1172/JCI30565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maggs DG, Buchanan TA, Burant CF, Cline G, Gumbiner B, et al. Metabolic effects of troglitazone monotherapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998;128:176–185. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-3-199802010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51a.Mayerson AB, Hundal RS, Dufour S, Lebon V, Befroy D, et al. The effects of rosiglitazone on insulin sensitivity, lipolysis, and hepatic and skeletal muscle triglyceride content in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:797–802. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.3.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mensink M, Hesselink MK, Russell AP, Schaart G, Sels JP, Schrauwen P. Improved skeletal muscle oxidative enzyme activity and restoration of PGC-1 alpha and PPAR beta/delta gene expression upon rosiglitazone treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2007;31:1302–1310. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Misra A, Khurana L. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;93:S9–S30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morino K, Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, Frattini J, et al. Reduced mitochondrial density and increased IRS-1 serine phosphorylation in muscle of insulin-resistant offspring of type 2 diabetic parents. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:3587–3593. doi: 10.1172/JCI25151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morino K, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in humans and their potential links with mitochondrial dysfunction. Diabetes. 2006;55(Suppl. 2):S9–S15. doi: 10.2337/db06-S002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neschen S, Morino K, Hammond LE, Zhang D, Liu ZX, et al. Prevention of hepatic steatosis and hepatic insulin resistance in mitochondrial acyl-CoA:glycerol-sn-3-phosphate acyltransferase 1 knockout mice. Cell Metab. 2005;2:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nilsson LH, Hultman E. Liver and muscle glycogen in man after glucose and fructose infusion. Scand J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 1974;33:5–10. doi: 10.3109/00365517409114190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ntambi JM, Miyazaki M, Stoehr JP, Lan H, Kendziorski CM, et al. Loss of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 function protects mice against adiposity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11482–11486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132384699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oral EA, Simha V, Ruiz E, Andewelt A, Premkumar A, et al. Leptin-replacement therapy for lipodystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:570–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patti ME, Butte AJ, Crunkhorn S, Cusi K, Berria R, et al. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8466–8471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1032913100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perseghin G, Price TB, Petersen KF, Roden M, Cline GW, et al. Increased glucose transport-phosphorylation and muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise training in insulin-resistant subjects. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:1357–1362. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610313351804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, Garcia R, Shulman GI. Impaired mitochondrial activity in the insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:664–671. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Feng J, Befroy D, Dziura J, et al. Increased prevalence of insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Asian-Indian men. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18273–18277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608537103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Nelson-Williams C, Nee Foo J, Zhang XM, et al. Common apolipoprotein C3 gene variants promote non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:1082–1089. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Savage DB, Bilz S, Solomon G, et al. The role of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12587–12594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705408104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Petersen KF, Hendler R, Price T, Perseghin G, Rothman DL, et al. 13C/31P NMR studies on the mechanism of insulin resistance in obesity. Diabetes. 1998;47:381–386. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petersen KF, Oral EA, Dufour S, Befroy D, Ariyan C, et al. Leptin reverses insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in patients with severe lipodystrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:1345–1350. doi: 10.1172/JCI15001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Phillips DI, Caddy S, Ilic V, Fielding BA, Frayn KN, et al. Intramuscular triglyceride and muscle insulin sensitivity: evidence for a relationship in nondiabetic subjects. Metabolism. 1996;45:947–950. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(96)90260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phillips SM, Green HJ, Tarnopolsky MA, Heigenhauser GJ, Grant SM. Progressive effect of endurance training on metabolic adaptations in working skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;270:E265–E272. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.270.2.E265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rahman SM, Dobrzyn A, Dobrzyn P, Lee SH, Miyazaki M, Ntambi JM. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 deficiency elevates insulin-signaling components and down-regulates protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B in muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11110–11115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934571100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Randle PJ, Garland PB, Hales CN, Newsholme EA. The glucose fatty-acid cycle. Its role in insulin sensitivity and the metabolic disturbances of diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1963;1:785–789. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(63)91500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reznick RM, Zong H, Li J, Morino K, Moore IK, et al. Aging-associated reductions in AMP-activated protein kinase activity and mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab. 2007;5:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roden M, Price TB, Perseghin G, Petersen KF, Rothman DL, et al. Mechanism of free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:2859–2865. doi: 10.1172/JCI118742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1461–1465. doi: 10.1038/ng.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rothman DL, Magnusson I, Cline G, Gerard D, Kahn CR, et al. Decreased muscle glucose transport/phosphorylation is an early defect in the pathogenesis of noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:983–987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rothman DL, Shulman RG, Shulman GI. 31P nuclear magnetic resonance measurements of muscle glucose-6-phosphate. Evidence for reduced insulin-dependent muscle glucose transport or phosphorylation activity in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89:1069–1075. doi: 10.1172/JCI115686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Qu X, Elder BD, Bilz S, et al. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32345–32353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Wang A, Beddow SA, Geisler JG, et al. Inhibition of protein kinase C-epsilon prevents hepatic insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:739–745. doi: 10.1172/JCI30400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Savage DB, Choi CS, Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Zhang D, et al. Reversal of diet-induced hepatic steatosis and hepatic insulin resistance by antisense oligonucleotide inhibitors of acetyl-CoA carboxylases 1 and 2. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:817–824. doi: 10.1172/JCI27300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Savage DB, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Disordered lipid metabolism and the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:507–520. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schalch DS, Kipnis DM. Abnormalities in carbohydrate tolerance associated with elevated plasma nonesterified fatty acids. J. Clin. Invest. 1965;44:2010–2020. doi: 10.1172/JCI105308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sebastian D, Herrero L, Serra D, Asins G, Hegardt FG. CPT I overexpression protects L6E9 muscle cells from fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;292:E677–E686. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00360.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shulman GI. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:171–176. doi: 10.1172/JCI10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shulman GI, Rothman DL, Jue T, Stein P, DeFronzo RA, Shulman RG. Quantitation of muscle glycogen synthesis in normal subjects and subjects with noninsulin-dependent diabetes by 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990;322:223–228. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001253220403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Storlien LH, Jenkins AB, Chisholm DJ, Pascoe WS, Khouri S, Kraegen EW. Influence of dietary fat composition on development of insulin resistance in rats. Relationship to muscle triglyceride and omega-3 fatty acids in muscle phospholipid. Diabetes. 1991;40:280–289. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Suwa M, Egashira T, Nakano H, Sasaki H, Kumagai S. Metformin increases the PGC-1alpha protein and oxidative enzyme activities possibly via AMPK phosphorylation in skeletal muscle in vivo. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006;101:1685–1692. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00255.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Szczepaniak LS, Babcock EE, Schick F, Dobbins RL, Garg A, et al. Measurement of intracellular triglyceride stores by H spectroscopy: validation in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:E977–E989. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.5.E977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Taylor R, Magnusson I, Rothman DL, Cline GW, Caumo A, et al. Direct assessment of liver glycogen storage by 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and regulation of glucose homeostasis after a mixed meal in normal subjects. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:126–132. doi: 10.1172/JCI118379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Taylor R, Price TB, Katz LD, Shulman RG, Shulman GI. Direct measurement of change in muscle glycogen concentration after a mixed meal in normal subjects. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:E224–E229. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.265.2.E224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Toledo FG, Menshikova EV, Azuma K, Radikova Z, Kelley CA, et al. Mitochondrial capacity in skeletal muscle is not stimulated by weight loss despite increases in insulin action and decreases in intramyocellular lipid content. Diabetes. 2008;57:987–994. doi: 10.2337/db07-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Toledo FG, Menshikova EV, Ritov VB, Azuma K, Radikova Z, et al. Effects of physical activity and weight loss on skeletal muscle mitochondria and relationship with glucose control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:2142–2147. doi: 10.2337/db07-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yu C, Chen Y, Cline GW, Zhang D, Zong H, et al. Mechanism by which fatty acids inhibit insulin activation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:50230–50236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]