Abstract

Translation is regulated predominantly at the initiation phase by several signal transduction pathways that are often usurped in human cancers, including the PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis. mTOR exerts unique administration over translation by regulating assembly of eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 4F, a heterotrimeric complex responsible for recruiting 40S ribosomes (and associated factors) to mRNA 5′ cap structures. Hence, there is much interest in targeted therapies that block eIF4F activity to assess the consequences on tumor cell growth and chemotherapy response. We report here that hippuristanol (Hipp), a translation initiation inhibitor that selectively inhibits the eIF4F RNA helicase subunit, eIF4A, resensitizes Eμ-Myc lymphomas to DNA damaging agents, including those that overexpress eIF4E—a modifier of rapamycin responsiveness. As Mcl-1 levels are significantly affected by Hipp, combining its use with the Bcl-2 family inhibitor, ABT-737, leads to a potent synergistic response in triggering cell death in mouse and human lymphoma and leukemia cells. Suppression of eIF4AI using RNA interference also synergized with ABT-737 in murine lymphomas, highlighting eIF4AI as a therapeutic target for modulating tumor cell response to chemotherapy.

Keywords: hippuristanol, eIF4A, Eμ-Myc, lymphoma, ABT-737, Mcl-1

Introduction

Evasion of apoptosis is a characteristic feature of tumor cells and a major cause of chemotherapy treatment failure. Chemoresistance can be attributed to an abundance shift in favor of the pro-survival proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Bcl-W, Mcl-1 and Bfl-1 (all defined by sequence conservation in 4 α-helical Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains).1 The activity of these proteins is restrained by a group of BH3-containing proteins, among which are Puma, Noxa, Bim, Bid, Bad and Bik.1 Anticancer therapies that target DNA integrity or replication indirectly trigger cell death in tumors. Consequently, tumors with elevated levels of Bcl-2, Mcl-1 or Bcl-XL tend to be refractory to chemo- and radiotherapy.1 Therefore, inhibiting the function or production of pro-survival family members represents a promising strategy for designing novel anticancer drugs to overcome these resistance mechanisms. With this in mind, ABT-737 was developed as a BH3 mimetic to selectively bind to Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and Bcl-W. This compound is effective at inducing tumor regression,2 but unfortunately, resistance arises as a consequence of elevated Mcl-1 and Bfl-1 expression—both of which are poorly targeted by this drug.1

We have previously demonstrated that Mcl-1 expression is translationally regulated by the PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway and contributes to mTOR-dependent pro-survival signaling.3 The PI3K/mTOR pathway selectively regulates protein synthesis through coordinated assembly of the rate-limiting translation initiation factor, eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 4F—a heterotrimeric complex comprising a cap-binding protein (eIF4E), a DEAD-box RNA helicase (eIF4A) and a large scaffolding protein (eIF4G).4 Increased signaling flux through the PI3K/mTOR pathway releases both eIF4E and eIF4A from their respective negative regulatory partners, 4E-BPs and PDCD4 (a tumor suppressor gene product), allowing these to assemble into the eIF4F complex.4 Both eIF4A and eIF4F are required for efficient ribosome recruitment to mRNA templates and different mRNA transcripts show variable dependencies on eIF4F/eIF4A for ribosome recruitment—a feature attributed to accessibility of the mRNA 5′ cap and local secondary structure.4 In this manner, mTOR control of eIF4F assembly is thought to act as a critical node for cell survival and proliferation.3, 5, 6 Altered flux through the PI3K/mTOR pathway is one of the most common lesions present in human cancers and is thought to lead to selective translational effects.7, 8 The production of Mcl-1 is particularly sensitive to perturbations affecting mTOR3 and eIF4E6 activity, eIF4A function9 and eIF4F integrity.10 As Mcl-1 has a short intrinsic protein half-life (t½=1–2 h),11, 12, 13 blocking Mcl-1 mRNA translation leads to its rapid depletion.

Translation initiation is an emerging chemotherapeutic target that remains to be fully explored. Several compounds that block translation initiation, either by interfering with eIF4E:eIF4G interaction or with eIF4A activity have been identified.14 In particular, interfering with eIF4A activity, using small molecules that act as chemical inducers of dimerization (that is, rocaglamides), exerts anti-neoplastic activity in vitro and in vivo.9, 15, 16 However, the indirect mechanism of the action of rocaglamides whereby they engage eIF4A to bind RNA in a sequence-independent manner9, 15 and the reported ability of rocaglamides to inhibit the Raf-MEK-ERK-S6K/eIF4B signaling pathway (which could indirectly have an impact on eIF4A's activity)17 have made it difficult to attribute antitumor activity of this class of inhibitors to a direct inhibition of eIF4A or eIF4F activity. In addition, rocaglamides are substrates for the multidrug resistance transporter, Pgp-1, imposing a significant challenge to their clinical development.18

We have recently described the biological properties of hippuristanol (Hipp), a natural product isolated from the coral Isis hippuris.19, 20 Hipp blocks translation initiation by binding to the C-terminal domain of eIF4A and antagonizing its interaction with RNA, a feature that can be rescued by eIF4A mutants engineered to be recalcitrant to Hipp binding.19, 20 Hipp does not inhibit other RNA helicases outside of the eIF4A family, an observation consistent with the lack of conservation of the Hipp binding site among these.19 Hipp's in vivo activity has not been significantly studied due to its limited availability, a shortcoming recently overcome by the elucidation of synthetic routes to its production.21, 22 Herein, we show that Hipp is capable of reversing drug resistance in tumors engineered to be dependent on PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. These studies were extended to demonstrate that suppressing eIF4A activity sensitizes human lymphoma cells to Bcl-2 targeted therapies. Our study identifies eIF4A as a therapeutic target for modulating tumor cell response to chemotherapy.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, cell culture and retroviral vectors

The generation of Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc, Pten+/– Eμ-Myc, Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2, Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1 and Eμ-Myc/eIF4E lymphomas has been described.3, 5 Mino, Ri-1, Namalwa, Sc-1, EoL-1 and MOLT-3 cell lines were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin. For culturing of hMB cells, RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin and 55 μℳ β-mercaptoethanol were used. Jeko-1 was cultured in RPMI supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin. Granta 519 and MV-4-11 were culture in DMEM and IMDM, respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin.

All retroviral packaging was performed using ecotropic Phoenix cells according to established protocols (http://www.stanford.edu/group/nolan/retroviral_systems/retsys.html). All murine lymphomas used in this study were maintained in B-cell media (45% DMEM, 45% IMDM, 55 μℳ β-mercaptoethanol and 10% fetal bovine serum) on γ-irradiated Arf−/− MEF feeder layers. Feeder layers comprised ∼25% confluent irradiated Arf−/− MEFs pre-incubated with B-cell Media for 3 days prior to the addition of lymphoma cells. Lymphomas were routinely split 1:3 every 2–3 days.

To generate Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shBim or Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shNoxa lymphomas, Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc lymphomas were infected with MLS retrovirus expressing the appropriate shRNA, followed by cell sorting on a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) to obtain the GFP+ population. Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2, Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1, p53−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 and p53−/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1 lymphomas were generated by infecting Arf−/−Eμ-Myc or p53−/−Eμ-Myc cells with MSCV-Bcl-2/EMCV/tRFP or MSCV-hMcl-1/EMCV/GFP followed by cell sorting on a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences).

Please see the Supplemental Methods and Materials for additional information.

Results

Targeting eIF4A chemosensitizes Myc-driven tumors to DNA damaging agents

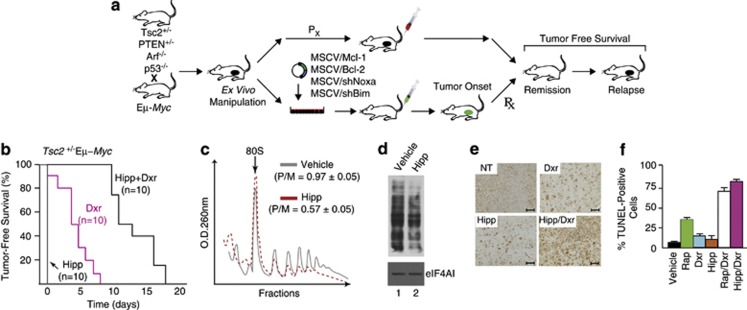

We took advantage of the Eμ-Myc model to assess the in vivo chemosensitization potential of Hipp using the approach outlined in Figure 1a. This model has been used to identify and characterize novel oncogenes and tumor suppressor pathways23 for testing the contribution of effector pathways to tumor initiation24 and maintenance,5 and for assessing response to chemotherapy.5, 24 We took advantage of engineered Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc and Pten+/−Eμ-Myc tumors as these are dependent on Mcl-1 for their survival,3 exhibit deregulated mTORC1 activity—a central regulator of translation initiation, and are genes for which mutations have been documented in human Burkitt's lymphoma.25 Treatment of mice bearing Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc lymphomas with Hipp did not induce any remissions at the doses tested, whereas doxorubicin (Dxr) or rapamycin (Rap) induce short-lived remissions (Figure 1b and Supplementary Figure S1A).3 Hipp however synergized with Dxr in vivo to extend tumor-free survival up to 17 days (Figure 1b; P<0.001 for Hipp+Dxr versus Dxr). Treatment of mice with Hipp lead to an in vivo reduction in protein synthesis in tumor cells, as assessed by a reduction in polysome/monosome ratio in tumor cells isolated from Hipp-treated mice (Figure 1c) and in vivo monitoring of protein synthesis in Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc tumor cells using SUnSET (Figure 1d).26 Likewise, exposing Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells to 50 nℳ Hipp led to a similar reduction in protein synthesis (Supplementary Figure S1B)—an effect that was not due to loss of cell viability (Supplementary Figure S1C). We observed an increase in apoptosis associated with Hipp's ability to alter the Dxr-response in Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc tumors, as judged by TUNEL staining of tumor tissue (Figures 1e and f, and Supplementary Figure S1D). No apparent difference in Ki-67 staining was detected among samples from Hipp-, Dxr- or Hipp+Dxr-treated mice (Supplementary Figure S1E).

Figure 1.

Hipp alters chemoresistance to DNA damaging agents in Eμ-Myc lymphomas. (a) Schematic illustrating generation of Eμ-Myc tumors of defined genotypes. Indicated are the ex vivo and in vivo manipulations used in this study to assess tumor growth and drug response. (b) Kaplan–Meier plot demonstrating response of Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc tumor-bearing mice to Hipp, Dxr, and Hipp+Dxr treatment. P<0.001 for Hipp+Dxr versus Dxr. (c) Hipp inhibits translation in Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc tumors in vivo. Mice bearing Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc tumors were treated with vehicle or Hipp (10 mg/kg) and 4 h later, tumors were excised, cytoplasmic extracts prepared and polysomes resolved. The position of 80S ribosomes is indicated and the polysome/monosome (P/M) ratios from three independent experiments denoted. (d) Hipp inhibits translation in vivo. Mice bearing Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc tumors were treated with vehicle or Hipp (10 mg/kg) and 4 h later were injected with 100 mg/kg puromycin. One hour later, tumors were excised, cytoplasmic extracts prepared, proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P by western blotting. Blots were probed with an anti-puromycin (upper panel) or an anti-eIF4AI (lower panel; loading control) antibody. (e) Representative micrographs of Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc lymphoma sections stained by TUNEL assay; bars represent 50 μm. C57BL/6 mice bearing well-palpable tumors were administered vehicle or Hipp. Twenty-four hours later, mice received Hipp, Dxr, or a combination of Hipp+Dxr. Six hours after treatment, tumors were extracted and stained. (f) Quantification of tumor cells positive for TUNEL staining following treatments described in Panel E and Suppl Figure 1. The cell count was obtained from two different fields taken from two sections (n=4). Results are expressed as the percent mean±s.d.

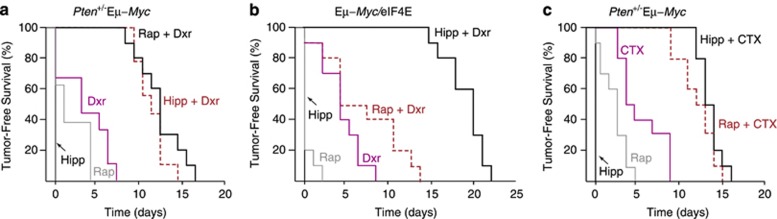

We then sought to determine whether the results described above for the Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc setting could be extended to different tumor genotypes and chemotherapeutic agents. We found that Hipp and Dxr also synergized in animals bearing Pten+/−Eμ-Myc (Figure 2a) or Eμ-Myc/eIF4E tumors (Figure 2b). The latter result is particularly noteworthy, as eIF4E is a genetic modifier of the Rap-response5 and elevated eIF4E levels lead to resistance to Rap+Dxr combination treatment (Figure 2b). These experiments extend the utility of Hipp in chemosensitizing cells to include tumors with lesions upstream of Tsc1/2 and downstream of mTOR. Hipp also synergized with cyclophosphamide (CTX), a standard-of-care chemotherapeutic used in the treatment of lymphomas (Figure 2c). These results indicate that Hipp is effective at resensitizing Myc-driven lymphomas to DNA damaging agents in vivo.

Figure 2.

Hipp chemosensitizes across tumor genotypes and to cyclophosphamide in Eμ-Myc lymphomas. (a) Kaplan–Meier plot illustrating the response of Pten+/−Eμ-Myc tumor-bearing mice to Dxr, Rap, Hipp, or a combination of these. n=10 mice per cohort. P<0.001 for Hipp+Dxr versus Dxr. (b) Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating response of Eμ-Myc/eIF4E tumor-bearing mice to Dxr, Rap or Hipp or a combination of these. n=10 mice per cohort. P<0.001 for Hipp+Dxr versus Dxr. (c) Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating response of Pten+/−Eμ-Myc tumor-bearing mice to cyclophosphamide (CTX), Rap, Hipp or a combination of these. n=10 mice per cohort. P<0.001 for Hipp+CTX versus CTX.

To address concerns regarding toxicity in vivo, we administered Hipp to mice at the effective doses and monitored body weight and liver function (Supplementary Figures S2A, B). Treated animals neither suffered from weight loss (Supplementary Figure S2A) nor showed any signs of liver cell damage as assessed by ALT and AST levels (Supplementary Figure S2B). Among the hematological parameters that we measured, there was little difference in B220+ (B-cell), Ly-6G+ (granulocytes), CD11b+ (monocyte/macrophages, granulocytes) and CD4+ (T cell) populations when comparing vehicle to Hipp-treated mice (Supplementary Figure S2C). These results are similar to what has been reported for silvestrol, a potent rocaglamide that interferes with eIF4A activity.9 Taken together, they indicate that transient inhibition of eIF4A is well tolerated at the organismal level. We also tested whether Hipp was a substrate for Pgp-1 (MDR1), a major drug efflux protein implicated in chemoresistance.27 A significant increase in IC50 of Dxr or silvestrol was noted in cells expressing high levels of Pgp-1 (Supplementary Figures S2D, E), consistent with these being substrates for Pgp-1.18 This phenomenon was not observed with Hipp indicating that it is not a Pgp-1 substrate (Supplementary Figure S2F).

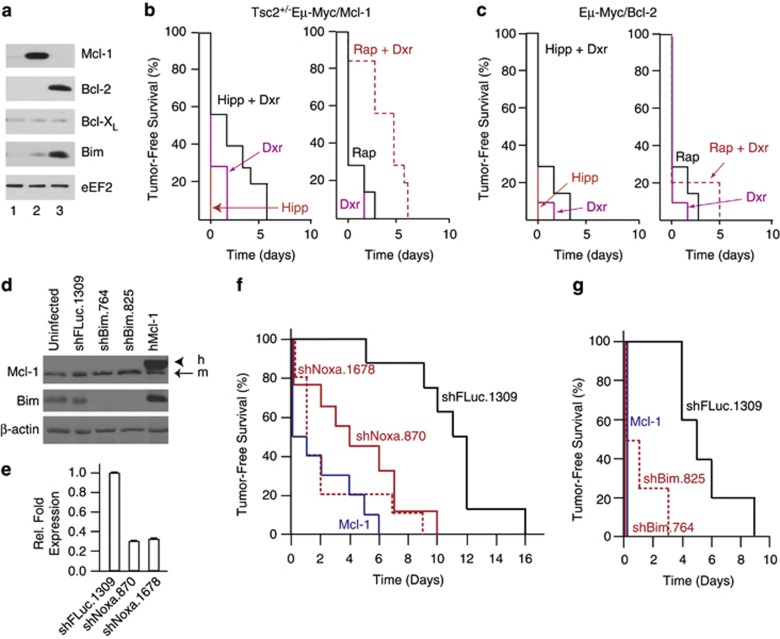

Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 are genetic modifiers of the Hipp+Dxr synergy response in Eμ-Myc lymphomas

Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 are known modifiers of drug sensitivity. To determine if altering Mcl-1 or Bcl-2 levels could affect the Hipp+Dxr synergy response, we generated Eμ-Myc lymphomas overexpressing these anti-apoptotic proteins (Figure 3a, lanes 2 and 3). Mice bearing these lymphomas displayed a poor response to Hipp+Dxr and Rap+Dxr combination treatments (Figures 3b and c). To extend these results, we tested whether the pro-apoptotic ‘BH3-only' family members, Bim (which interacts with Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Bcl-W, and Mcl-1) and Noxa (which interacts with Mcl-1) could also modulate the tumor response to Hipp/Dxr. Two shRNAs for each target were developed and caused a greater than four-fold reduction in Bim protein (Figure 3d) and Noxa mRNA (Figure 3e) levels. (Note that we could not probe for NOXA protein levels due to poor reactivity of available antibodies.) Infection of Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc tumor cells with either Bim or Noxa shRNAs significantly dampened the in vivo ability of Hipp and Dxr to synergize (Figures 3f and g). To determine if these effects were due to altered sensitivity to Hipp and/or Dxr, Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc lymphomas were exposed ex vivo to single agents and cell viability was assessed. A nearly two- and five- fold increase in the resistance to Hipp and Dxr, respectively, was observed upon ectopic overexpression of Mcl-1 (Supplementary Figures S3A, B). A smaller but reproducible increase in the resistance to Hipp and Dxr was noted upon Bim and Noxa suppression in Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc lymphomas (Supplementary Figures S3C–F). (These experiments could not be performed with Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 tumor cells since we are unable to propagate these ex vivo.) Although these results do not rule out a contribution from tumor cell extrinsic responses to the Hipp+Dxr-response in vivo, they do indicate that components of the intrinsic cell death pathway are major modifiers of the Hipp+Dxr synergy response in vivo and do so at least in part by affecting cell sensitivity to Hipp and Dxr.

Figure 3.

Components of the intrinsic cell death pathway are genetic modifiers of Hipp-mediated chemosensitivity. (a) Western blot analysis of Mcl-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Bim in Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc tumors. Extracts were derived from: Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc (lane 1); Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1 (lane 2); and Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 (lane 3) cells. (b) Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating response of Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1 tumor-bearing mice to Hipp, Dxr, Rap or a combination of treatments. n=10 mice per cohort, P=0.157 for Hipp+Dxr versus Dxr. (c) Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating response of Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 tumor-bearing mice to Hipp, Dxr, Rap or a combination of treatments. n=10 mice per cohort, P=0.118 for Hipp+Dxr versus Dxr. (d) Western blot analysis of Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc lymphomas expressing the indicated shRNAs or Mcl-1 cDNA (lane 5) and probed with antibodies to the proteins denoted to the left of the panels. h, human; m, mouse. (e) Quantitation of Noxa RNA levels by RT-qPCR from total RNA isolated from Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc lymphomas expressing the indicated shRNAs. The values were normalized to β-actin mRNA. (f) Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating response of Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc tumor-bearing mice expressing the indicated shRNAs, or overexpressing Mcl-1, to Hipp+Dxr combination treatment. n=8 (Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shFLuc.1309), n=9 (Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shNoxa.870), n=10 (Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shNoxa.1678), n=10 (Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1); P<0.001 for Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shFLuc.1309 compared to Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shNoxa.870. (g) Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating response of Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc tumor-bearing mice expressing the indicated shRNAs or overexpressing Mcl-1 to Hipp+Dxr combination treatment. n=5 (Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shFLuc.1309), n=4 (Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shBim.764), n=4 (Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shBim.825), n=5 (Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1); P<0.001 for (Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shFLuc.1309 compared to Tsc2+/–Eμ-Myc/shBim.825). (Note that the shFluc.1309 cohort in this experiment was independently derived from the one present in panel 2F and shows a slightly shortened tumor-free survival period.).

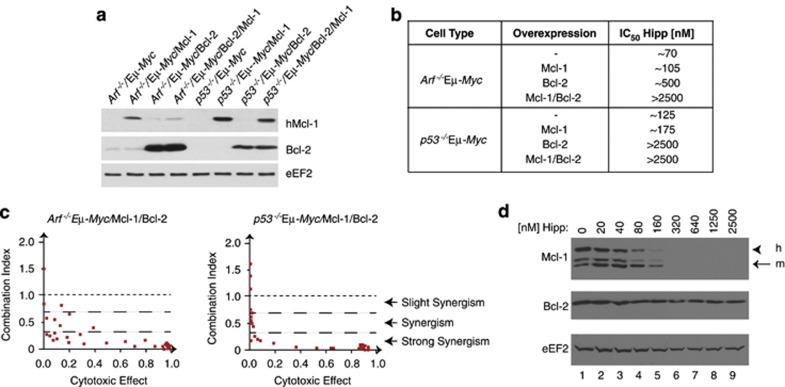

Hipp sensitizes Myc-driven tumors to Bcl-2-targeted therapeutics

The effectiveness of Hipp in reducing Mcl-1 levels (see below) and the role that Bcl-2 family members have in mediating resistance to Hipp's chemosensitizing properties (Figure 3) suggested that a combination of Hipp and Bcl-2 targeted therapy might be an appropriate strategy to curtail chemoresistance arising from the activation of the intrinsic cell death pathway. To test this, we generated a series of isogenic lines ectopically expressing Mcl-1, Bcl-2 or both, using Arf−/−Eμ-Myc and p53−/−Eμ-Myc cells (Figure 4a, Supplementary Figures S4–S6). Ectopic expression of Mcl-1 or Bcl-2 in Arf−/−Eμ-Myc or p53−/−Eμ-Myc cells produced lines that displayed an increase in the Hipp IC50, with Bcl-2 expressing cells demonstrating a more significant shift than cells expressing Mcl-1 (Figure 4b and Supplementary Figure S4). Expression of Bcl-2 in Arf−/−Eμ-Myc or p53−/−Eμ-Myc cells sensitized these to ABT-737 (Supplementary Figure S4)—an expected phenomenon that is thought to be the consequence of elevated BH3 protein levels predisposing to Bcl-2 dependence and response to ABT-737.28 No synergy was observed between Hipp and ABT-737 in Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1 or p53−/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1 cells (Supplementary Figures S5A and S5C). Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 and p53−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 showed synergy at concentrations of Hipp >160 nℳ (Supplementary Figures S5B, S5D–S5F). Although there was little synergy between Hipp and ABT-737 in either Arf−/−Eμ-Myc or p53−/−Eμ-Myc parental cell lines, ectopic expression of Bcl-2 and Mcl-1 led to a strong synergistic relationship between Hipp and ABT-737 (Figure 4c and Supplementary Figure S6). Mcl-1 levels in Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1/Bcl-2 cells are significantly depleted upon exposure of cells to Hipp (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Hipp and ABT-737 synergize in Myc-driven lymphomas. (a) Western blot analysis of Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 in the indicated tumor genotypes. hMcl-1 was detected using the human-specific antibody, AHP2138 (AbD Serotec). (b) Table showing the IC50s of the indicated cell lines when exposed to Hipp for 18 hrs. (c) Combination index (CI) plot displaying the synergistic effect for Hipp and ABT-737 in Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1/Bcl-2 and p53−/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1/Bcl-2 cells. The primary data were taken from Supplementary Figures S6B and S6D, respectively. Each dot represents the CI value of a specific Hipp+ABT-737 drug combination. (d) Western blot illustrating sensitivity of Mcl-1 production to Hipp in Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Mcl-1/Bcl-2 cells. Cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of Hipp for 18 h, at which point cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by western blotting with antibodies recognizing the proteins indicated to the left of the panels. h, human; m, murine. Both human and mouse Mcl-1 proteins were detected using the AHP-1249 antibody from AbD Serotec.

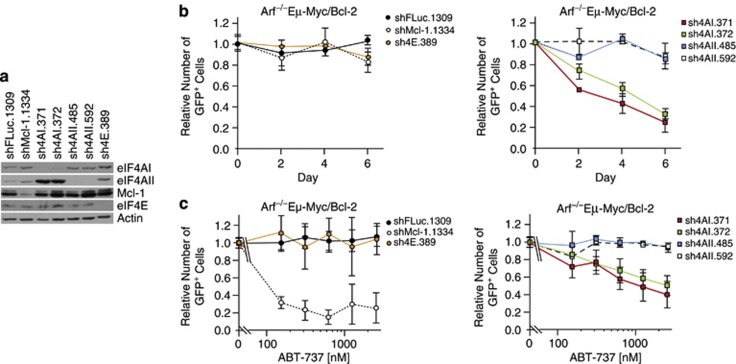

Suppression of eIF4AI is sufficient to chemosensitize Myc-driven tumors to Bcl-2 targeted therapeutics

Mammalian cells encode for two eIF4A isoforms, eIF4AI and eIF4AII, that share 90% similarity at the protein level and have non-redundant but overlapping activities.29, 30 As Hipp inhibits both isoforms, we sought to determine if RNAi-mediated suppression of either or both isoform could phenocopy the ABT-737 sensitization. Long-term (6 days) suppression of eIF4AI, but not eIF4AII, was lethal (Figures 5a and b), with little change in the percentage of viable uninfected cells (Supplementary Figure S7A). This effect was p53-dependent, as it was significantly blunted in p53−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 cells (Supplementary Figure S7B). Suppression of eIF4AII, eIF4E or Mcl-1, as well as expression of a neutral shRNA targeting Firefly luciferase (shFLuc) had a minor impact on the GFP+ cell population (∼20% change) (Figure 5b, Supplementary Figure S7B). These results indicate that long-term suppression of eIF4AI in Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 cells is lethal.

Figure 5.

Suppression of eIF4AI, but not eIF4AII, sensitizes to ABT-737 in Myc-driven lymphomas. (a) Western blot analysis of eIF4AI and eIF4AII levels in p53−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 cells infected with retrovirus expressing the indicated shRNAs. (b) Competition assay of Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 lymphomas infected with retroviruses expressing the indicated shRNAs. Flow cytometry was used to determine the %GFP+ population during a 6-day time course following the last infection. Data from cells infected with shRNAs to FLuc, Mcl-1 and eIF4E are grouped in the left panel, while those targeting eIF4AI/II are grouped in the right panel for clarity. Error bars indicate SEM; n=3. (c) Synergy between eIF4AI suppression and ABT-737 in Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 lymphomas. Following the last infection, cells were exposed to vehicle or the indicated concentrations of ABT-737 for 18 h at which time flow cytometry was used to determine the %GFP+ cells. Data from cells infected with shRNAs to FLuc, Mcl-1 and eIF4E are grouped in the left panel, whereas those targeting eIF4AI/II are grouped in the right panel for clarity. Error bars indicate s.e.m.; n=3.

To assess if suppression of eIF4AI and/or eIF4AII would synergize with ABT-737 on a shorter time scale, we infected Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 and p53−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 cells with retroviruses expressing shRNAs and exposed the cells to either vehicle or ABT-737 for a short-term pulse (that is, 18 hours) (Figure 5c, Supplementary Figure S7C). We then monitored the fitness of shRNA-expressing cells (GFP+) relative to uninfected cells (GFP−) in a competition assay to detect altered sensitivity to ABT-737. The results demonstrate that ABT-737 had little effect on the viability of Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 expressing shFLuc.1309, whereas loss of viability was apparent upon Mcl-1 suppression (Figure 5c, left panel; see shMcl-1.1334). Suppression of eIF4AI, but not eIF4AII, led to a dose-dependent loss in Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 cell viability in the presence of ABT-737 (Figure 5c, right panel), which was significantly blunted upon loss of p53 (Supplementary Figure S7C, right panel). These results indicate that suppression of eIF4AI in Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 cells is sufficient to synergize with ABT-737.

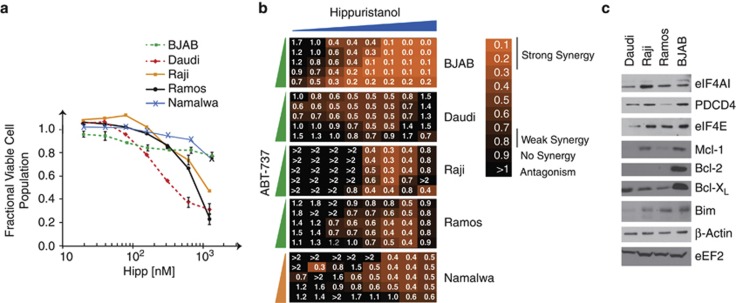

Hipp and ABT-737 synergize in human lymphoma and leukemia tumor cells

To extend our results to the human setting, we tested the sensitivity of a number of lymphoma and leukemic tumor cells to Hipp (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure S8). Viability of the Burkitt's lymphoma lines, Daudi, Ramos and Raji was reduced by Hipp (with IC50s ranging from 300 nℳ to 1.25 μℳ), whereas BJAB and Namalwa were relatively resistant with 80% of cells surviving at concentrations as high as 1.25 μℳ (Figure 6a). In addition, many other lymphoma/leukemic lines tested appeared relatively resistant to Hipp, with MV-4-11 and Mino being the more sensitive ones. Lines hMB, Granta 519 and Sc-1 showed less than a 10% reduction in viability when exposed to concentrations as high as 1250 nℳ (Supplementary Figure S8A). However, despite this, we found synergy between Hipp and ABT-737 in all Burkitt's (Figure 6b) and lymphoma/leukemia lines (Supplementary Figure S8B) tested, although the extent varied among cell lines. In contrast, no synergy was observed between Hipp (5–625nℳ) and ABT-737 (156 nℳ–2.5 μℳ) in immortalized hTert-BJ cells (R Cencic, unpublished data), hinting that such activity may not extend to the non-transformed setting. No correlation was apparent between Hipp sensitivity (Figure 6a and Supplementary Figure S8A) and expression levels of eIF4A or PDCD4 (a repressor of eIF4A) (Figure 6c and Supplementary Figure S8C) in the cell lines tested. As well, Hipp+ABT-737 synergy appeared independent of p53 mutation status and levels of Bcl-2, Mcl-1, Bcl-XL or Bim (Figure 6c and Supplementary Figure S8C). These results indicate that ABT-737 and Hipp synergize in the majority of transformed lymphoma/leukemia lines tested.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity of Burkitt's lymphoma cells to Hipp. (a) Dose response curves assessing sensitivity of Burkitt's lymphoma cells to Hipp. Cells were exposed to the indicated drug concentrations for 18 h after which time the fraction of viable cell population was determined by flow cytometry. The data are representative of three different experiments with the s.d. presented. (b) Heat maps illustrating the combination index (CI) displaying the synergistic effect for the combination of and ABT-737 in Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Synergy is defined as 0.25<CI<0.75 whereas strong synergy is CI<0.25. Concentrations of ABT-737 ranged from 2.5 μℳ to 156 nℳ (green dose line) or from 10 μℳ to 0.625 μℳ (orange dose line) with two-fold step dilutions. Hipp dilutions ranged from 2.5 μℳ to 20 nℳ with 2-step dilutions. (c) Western blot analysis of extracts prepared from the indicated tumor cell lines. The proteins detected by immunoblotting are indicated to the right.

Discussion

Mutations leading to constitutive activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling axis are among the most common found in human tumors.31 There is thus intensive effort to develop inhibitors of this pathway, such as rapalogs, TOR-kinase inhibitors (KI) and dual-specificity PI3K/TOR inhibitors. The presence of a TOR-S6K-IRS1 negative feedback loop,32 the ability of elevated eIF4E levels to impart resistance to Rap33 and PI3K/TOR KIs,34 and the association of TSC1 loss with everolimus resistance in the clinic35 highlight the barriers facing clinical development of PI3K/TOR inhibitors. By targeting downstream of the mTOR/eIF4F axis, all of these potential resistance mechanisms are bypassed. Here, we explored the ability of Hipp, a selective and potent inhibitor of the DEAD-box RNA helicases eIF4AI and eIF4AII19, 20 to sensitize Myc-driven lymphomas to both standard-of-care and molecular-targeted chemotherapies. We find that Hipp can synergize with DNA damaging agents in Eμ-Myc lymphomas harboring lesions upstream or downstream of mTOR to overcome chemoresistance. Most notably, Hipp resensitizes eIF4E-overexpressing Eμ-Myc lymphomas to Dxr indicating that eIF4E-induced chemoresistance in these tumors can be overcome by inhibiting the eIF4A downstream helicase. In addition, the ability to manipulate the intrinsic apoptotic effectors in the Eμ-Myc model enabled us to identify Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 as genetic modifiers of the Hipp response (Figure 3). This in turn suggested a strategy by which acquired Mcl-1 or Bcl-2 resistance could be targeted—through combining Hipp with the Bcl-2 family inhibitor, ABT-737.2

Although ABT-737 is efficacious as a single agent in several clinically relevant settings, many cancers are refractory to ABT-737 treatment.36, 37, 38 As ABT-737 only binds weakly to Mcl-1, cells engineered to overexpress Mcl-1 are universally resistant to ABT-737 treatment.39 Indeed, human lymphomas derived from parental lines initially sensitive to ABT-737 treatment acquire resistance primarily through upregulation of Mcl-1 (and A1/Bfl-1).40, 41 Mcl-1 is 1 of the top 10 amplified genes in human tumors, making it likely to be a major contributor to ABT-737 (and to its orally bioavailable version, ABT-263) resistance in the clinic.42 Methods to limit Mcl-1 expression (such as targeting translation by Hipp) can have a significant impact on the anticancer arsenal as these, in principle, should resensitize resistant cells to ABT-737 intervention.39

Although Hipp is able to synergize with ABT-737 in both Arf−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 and p53−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 cells (at concentrations >160 nℳ) (Supplementary Figures S5E, S5F), p53−/−Eμ-Myc/Bcl-2 cells were recalcitrant to RNAi-mediated suppression of eIF4AI and high concentrations of ABT-737 (Supplementary Figure S7C). We attribute these unequal responses to incomplete eIF4AI inhibition obtained by RNAi compared to complete inhibition of RNA binding achievable with Hipp in cells. The ability of Hipp and ABT-737 to synergize in Bcl-2-overexpressed (as well as Bcl-2/Mcl-1 doubly overexpressed) derived cell lines (Supplementary Figures S5E, S5F, and Figure 4) but not in the parental Arf−/−Eμ-Myc and p53−/−Eμ-Myc lines (Supplementary Figure S6) can be rationalized by the accompanying stabilization and increase in Bim levels seen upon overexpression of Bcl-2 in Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells (Figure 3a). This excess in Bim protein content binds to and inhibits all anti-apoptotic Bcl-2-like proteins, effectively ‘priming' the mitochondrion for the intrinsic cell death pathway—this explains how cells with high Bcl-2 levels can nevertheless be sensitive to treatment with ABT-737.43, 44

However, there may be situations where extraordinarily high levels of Bcl-2 and/or Mcl-1 impair the ability of translation initiation inhibitors to reduce these to levels sufficient to trigger an apoptotic response. The strategy described in this study may not be effective in such situations. As well, in ABT-737/Hipp synergy experiments, we utilized engineered murine lymphomas where the manipulated anti-apoptotic family members had been introduced into mature tumors. Tumors arising from situations where deregulated expression of the anti-apoptotic drivers directly contribute to initiation or maintenance may respond differently to ABT-737/Hipp combination treatments.

Mutations in eIF4AI are not prevalent in human tumors and ectopic expression of eIF4AI in the Eμ-Myc model is not transforming (unlike eIF4E) (J Pelletier, data not shown). However, eIF4AI is one of the more abundant translation initiation factors, present at nearly three copies per ribosome.30 This contrasts to the rate-limiting levels of the eIF4E subunit of eIF4F—estimated at ∼0.3 copies/ribosome.30 It would thus be difficult to rationalize what translational consequences, and hence selective advantage, increasing eIF4AI levels would have when not limiting for translation initiation. Indeed, we found no correlation in vitro between eIF4AI levels and Hipp sensitivity among the lymphoma/leukemia cells tested (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure S8). However, what might be more important in some settings are the levels of PDCD4—a tumor suppressor gene product that sequesters eIF4AI and affects translation of selective mRNAs. Interestingly, loss of PDCD4 leads to spontaneous lymphoma development in null mice45 and is an unfavorable prognostic indicator.46, 47 However, in the human lymphomas and leukemias that we analyzed, neither Hipp sensitivity nor Hipp+ABT-737 synergy correlated with differences in PDCD4 levels (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure S8). Other eIF4A-interacting partners, such as BC-148 or eIF4G2 (p97/DAP5),49 may have a role in affecting eIF4A availability for eIF4F-dependent translation, and their role in molding the cancer cell proteome remains to be explored.

We have previously used inhibitors of translation elongation50 or initiation10, 15 to overcome chemoresistance in the Eμ-Myc model. However, in general the use of translation elongation inhibitors as chemotherapeutics show significant toxicity and a poor therapeutic window. One exception appears to be homoharringtonine (omacetaxine mepesuccinate), which has been approved for use against chronic myelogenous leukemia. Among initiation inhibitors tested in the Eμ-Myc model, rocaglamides15 have a complex mechanism of action making it difficult to ascribe any physiological effects to direct inhibition of eIF4F/eIF4A activity14 (see Introduction). As well, both rocaglamides (that is, silvestrol) and homoharringtonine are Pgp-1 substrates.18 Hipp on the other hand is not a Pgp-1 substrate (Supplementary Figure S2F) and has a straightforward mechanism of action on translation that leads to inhibition of eIF4A RNA binding.19, 20 One caveat to the interpretation of our data is that we do not know if Hipp (or ABT-737) accumulates to the same levels in the different cell lines used. We do know however that the IC50 for translation inhibition by Hipp among many different cell lines tested does not vary significantly (data not shown), arguing against large variations in intracellular concentrations.

We note that the effects reported here for Hipp are likely an underestimation of what is achievable with this compound in vivo. We have not optimized dosing regiments in our in vivo experiments due to limitations in compound availability, have not yet determined a maximum-tolerated dose due to solubility issues at concentrations >20 mg/ml, and have not developed strategies to prevent epimerization that leads to compound inactivation.20 Dose-limiting bioavailability could be the reason why viability of Tsc2+/−Eμ-Myc cells is inhibited in vitro (Supplementary Figure S3) yet little effect on tumor burden is apparent in vivo in cohorts treated with only Hipp (Figure 1b). Nonetheless, the concentrations we used in vivo were sufficient to obtain significant reversal of chemoresistance, while showing little toxicity towards the host (Figures 1, 2 and Supplementary Figure S2). In some xenograft models, Hipp has shown single-agent activity,51, 52 suggesting that some tumors may be quite susceptible to the inhibition of translation initiation in vivo. In summary, our results highlight the potential of curtailing translation initiation by targeting eIF4A activity to reverse drug resistance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Elias George (McGill University) for the kind gift of Pgp-1-expressing HeLa cells. Gabriela Galicia-Vázquez is a recipient of a Cole Foundation Fellowship and was also supported by a CIHR Strategic Training Initiative in Chemical Biology. This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-106530 to JP).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Blood Cancer Journal website (http://www.nature.com/bcj)

Supplementary Material

References

- Davids MS, Letai A. Targeting the B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 2 family in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3127–3135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, et al. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature. 2005;435:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nature03579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JR, Hippo Y, Robert F, Chen SM, Malina A, Lin CJ, et al. mTORC1 promotes survival through translational control of Mcl-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10853–10858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804821105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel HG, De Stanchina E, Fridman JS, Malina A, Ray S, Kogan S, et al. Survival signalling by Akt and eIF4E in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nature. 2004;428:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature02369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel HG, Silva RL, Malina A, Mills JR, Zhu H, Ueda T, et al. Dissecting eIF4E action in tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3232–3237. doi: 10.1101/gad.1604407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhar VK, Viale A, Socci ND, Wiedmann M, Hu X, Holland EC. Oncogenic Ras and Akt signaling contribute to glioblastoma formation by differential recruitment of existing mRNAs to polysomes. Mol Cell. 2003;12:889–901. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmy K, Halliday J, Fomchenko E, Setty M, Pitter K, Hafemeister C, et al. Identification of global alteration of translational regulation in glioma in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cencic R, Carrier M, Galicia-Vazquez G, Bordeleau ME, Sukarieh R, Bourdeau A, et al. Antitumor activity and mechanism of action of the cyclopenta[b]benzofuran, silvestrol. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cencic R, Hall DR, Robert F, Du Y, Min J, Li L, et al. Reversing chemoresistance by small molecule inhibition of the translation initiation complex eIF4F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1046–1051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011477108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig RW. MCL1 provides a window on the role of the BCL2 family in cell proliferation, differentiation and tumorigenesis. Leukemia. 2002;16:444–454. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuconati A, Mukherjee C, Perez D, White E. DNA damage response and MCL-1 destruction initiate apoptosis in adenovirus-infected cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2922–2932. doi: 10.1101/gad.1156903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhawan D, Fang M, Traer E, Zhong Q, Gao W, Du F, et al. Elimination of Mcl-1 is required for the initiation of apoptosis following ultraviolet irradiation. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1475–1486. doi: 10.1101/gad.1093903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malina A, Mills JR, Pelletier J. Emerging therapeutics targeting mRNA translation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a012377. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordeleau ME, Robert F, Gerard B, Lindqvist L, Chen SM, Wendel HG, et al. Therapeutic suppression of translation initiation modulates chemosensitivity in a mouse lymphoma model. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2651–2660. doi: 10.1172/JCI34753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas DM, Edwards RB, Lozanski G, West DA, Shin JD, Vargo MA, et al. The novel plant-derived agent silvestrol has B-cell selective activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2009;113:4656–4666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-175430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polier G, Neumann J, Thuaud F, Ribeiro N, Gelhaus C, Schmidt H, et al. The natural anticancer compounds rocaglamides inhibit the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway by targeting prohibitin 1 and 2. Chem. Biol. 2012;19:1093–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SV, Sass EJ, Davis ME, Edwards RB, Lozanski G, Heerema NA, et al. Resistance to the translation initiation inhibitor silvestrol is mediated by ABCB1/P-glycoprotein overexpression in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. AAPS J. 2011;13:357–364. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9276-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist L, Oberer M, Reibarkh M, Cencic R, Bordeleau ME, Vogt E, et al. Selective pharmacological targeting of a DEAD box RNA helicase. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordeleau M-E, Mori A, Oberer M, Lindqvist L, Chard LS, Higa T, et al. Functional characterization of IRESes by an inhibitor of the RNA helicase eIF4A. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:213–220. doi: 10.1038/nchembio776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindar K, Reddy MS, Lindqvist L, Pelletier J, Deslongchamps P. Synthesis of the antiproliferative agent hippuristanol and its analogues via suarez cyclizations and hg(ii)-catalyzed spiroketalizations. J Org Chem. 2011;76:1269–1284. doi: 10.1021/jo102054r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Dang Y, Liu JO, Yu B. Expeditious synthesis of hippuristanol and congeners with potent antiproliferative activities. Chemistry. 2009;15:10356–10359. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuoppo C, Miething C, Lindqvist L, Reyes J, Ruse C, Appelmann I, et al. A tumour suppressor network relying on the polyamine-hypusine axis. Nature. 2012;487:244–248. doi: 10.1038/nature11126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CJ, Nasr Z, Premsrirut PK, Porco JA, Jr, Hippo Y, Lowe SW, et al. Targeting synthetic lethal interactions between Myc and the eIF4F complex impedes tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2012;1:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz R, Young RM, Ceribelli M, Jhavar S, Xiao W, Zhang M, et al. Burkitt lymphoma pathogenesis and therapeutic targets from structural and functional genomics. Nature. 2012;490:116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt EK, Clavarino G, Ceppi M, Pierre P. SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:275–277. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer BC, Gillet JP, Patel C, Baer MR, Bates SE, Gottesman MM. Drug resistance: still a daunting challenge to the successful treatment of AML. Drug Resist Updat. 2012;15:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J, Carlson N, Takeyama K, Dal Cin P, Shipp M, Letai A. BH3 profiling identifies three distinct classes of apoptotic blocks to predict response to ABT-737 and conventional chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers GW, Jr., Komar AA, Merrick WC. eIF4A: the godfather of the DEAD box helicases. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2002;72:307–331. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(02)72073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galicia-Vazquez G, Cencic R, Robert F, Agenor AQ, Pelletier J. A cellular response linking eIF4AI activity to eIF4AII transcription. RNA. 2012;18:1373–1384. doi: 10.1261/rna.033209.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan TL, Cantley LC. PI3K pathway alterations in cancer: variations on a theme. Oncogene. 2008;27:5497–5510. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington LS, Findlay GM, Gray A, Tolkacheva T, Wigfield S, Rebholz H, et al. The TSC1-2 tumor suppressor controls insulin-PI3K signaling via regulation of IRS proteins. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:213–223. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel HG, Malina A, Zhao Z, Zender L, Kogan SC, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. Determinants of sensitivity and resistance to rapamycin-chemotherapy drug combinations in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7639–7646. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic N, Utermark T, Widlund HR, Roberts TM. PI3K-targeted therapy can be evaded by gene amplification along the MYC-eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E699–E708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108237108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer G, Hanrahan AJ, Milowsky MI, Al-Ahmadie H, Scott SN, Janakiraman M, et al. Genome sequencing identifies a basis for everolimus sensitivity. Science. 2012;338:221. doi: 10.1126/science.1226344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Sinicrope FA. BH3 mimetic ABT-737 potentiates TRAIL-mediated apoptotic signaling by unsequestering Bim and Bak in human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2944–2951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutuk O, Letai A. Alteration of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is key to acquired paclitaxel resistance and can be reversed by ABT-737. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7985–7994. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witham J, Valenti MR, De-Haven-Brandon AK, Vidot S, Eccles SA, Kaye SB, et al. The Bcl-2/Bcl-XL family inhibitor ABT-737 sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to carboplatin. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7191–7198. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Delft MF, Wei AH, Mason KD, Vandenberg CJ, Chen L, Czabotar PE, et al. The BH3 mimetic ABT-737 targets selective Bcl-2 proteins and efficiently induces apoptosis via Bak/Bax if Mcl-1 is neutralized. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler M, Butterworth M, Majid A, Walewska RJ, Sun XM, Dyer MJ, et al. Concurrent up-regulation of BCL-XL and BCL2A1 induces approximately 1000-fold resistance to ABT-737 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;113:4403–4413. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yecies D, Carlson NE, Deng J, Letai A. Acquired resistance to ABT-737 in lymphoma cells that up-regulate MCL-1 and BFL-1. Blood. 2010;115:3304–3313. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Gaizo Moore V, Brown JR, Certo M, Love TM, Novina CD, Letai A. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia requires BCL2 to sequester prodeath BIM, explaining sensitivity to BCL2 antagonist ABT-737. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:112–121. doi: 10.1172/JCI28281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino D, Khaw SL, Glaser SP, Anderson DJ, Belmont LD, Wong C, et al. Bcl-2, Bcl-x(L), and Bcl-w are not equivalent targets of ABT-737 and navitoclax (ABT-263) in lymphoid and leukemic cells. Blood. 2012;119:5807–5816. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-400929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard A, Hilliard B, Zheng SJ, Sun H, Miwa T, Song W, et al. Translational regulation of autoimmune inflammation and lymphoma genesis by programmed cell death 4. J Immunol. 2006;177:8095–8102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allgayer H. Pdcd4, a colon cancer prognostic that is regulated by a microRNA. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;73:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudduluru G, Medved F, Grobholz R, Jost C, Gruber A, Leupold JH, et al. Loss of programmed cell death 4 expression marks adenoma-carcinoma transition, correlates inversely with phosphorylated protein kinase B, and is an independent prognostic factor in resected colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1697–1707. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Pestova TV, Hellen CU, Tiedge H. Translational control by a small RNA: dendritic BC1 RNA targets eIF4A helicase mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3008–3019. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01800-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imataka H, Olsen HS, Sonenberg N. A new translational regulator with homology to eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G. EMBO J. 1997;16:817–825. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert F, Carrier M, Rawe S, Chen S, Lowe S, Pelletier J. Altering chemosensitivity by modulating translation elongation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higa T, Tanaka J, Tsukitani Y, Kikuchi H. Hippuristanols, cytotoxic polyoxygenated steroids from the gorgonian Isis hippuris. Chem Lett. 1981;10:1647–1650. [Google Scholar]

- Tsumuraya T, Ishikawa C, Machijima Y, Nakachi S, Senba M, Tanaka J, et al. Effects of hippuristanol, an inhibitor of eIF4A, on adult T-cell leukemia. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.