Abstract

Curcumin is a polyphenol derived from turmeric with recognized antioxidant properties. Hexavalent chromium is an environmental toxic and carcinogen compound that induces oxidative stress. The objective of this study was to evaluate the potential protective effect of curcumin on the hepatic damage generated by potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) in rats. Animals were pretreated daily by 9-10 days with curcumin (400 mg/kg b.w.) before the injection of a single intraperitoneal of K2Cr2O7 (15 mg/kg b.w.). Groups of animals were sacrificed 24 and 48 h later. K2Cr2O7-induced damage to the liver was evident by histological alterations and increase in the liver weight and in the activity of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, and alkaline phosphatase in plasma. In addition, K2Cr2O7 induced oxidative damage in liver and isolated mitochondria, which was evident by the increase in the content of malondialdehyde and protein carbonyl and decrease in the glutathione content and in the activity of several antioxidant enzymes. Moreover, K2Cr2O7 induced decrease in mitochondrial oxygen consumption, in the activity of respiratory complex I, and permeability transition pore opening. All the above-mentioned alterations were prevented by curcumin pretreatment. The beneficial effects of curcumin against K2Cr2O7-induced liver oxidative damage were associated with prevention of mitochondrial dysfunction.

1. Introduction

Curcumin or diferuloylmethane (1,7-bis[4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl]-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione) is a hydrophobic polyphenol derived from turmeric: the rhizome of the herb Curcuma longa [1]. Traditionally, turmeric has been used in therapeutic preparations for various ailments in different parts of the world [2]. At present, turmeric is used as a dietary spice, by the food industry as additive, flavouring, preservative and as colouring agent in foods and textiles [3, 4]. Curcumin is a major component of turmeric and it has been shown to exhibit antioxidant [5], antimicrobial [6], anti-inflammatory [7], and anticarcinogenic [8] activities.

The antihepatotoxic effects of curcumin against chemically induced hepatic damage are well documented, and they have been attributed to its intrinsic antioxidant properties [9]. Thus, curcumin has shown to protect liver against hepatic injury and fibrogenesis by suppressing hepatic inflammation [10], attenuating hepatic oxidative stress [11, 12], increasing expression of the xenobiotic detoxifying enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutathione-S-transferase (GST), glutathione reductase (GR), and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase [5, 13, 14], inhibiting hepatic stellate cells activation [15–17], and supporting the mitochondrial function [18].

On the other hand, chromium exists in several oxidation states, being hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] and trivalent chromium [Cr(III)] the most stable forms. Cr(III) is predominantly present in the environment and in salts used as micronutrients and dietary supplements [19]. Cr(VI) salts such as potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) or chromic acid are widely used in leather, chrome-plating, and dye-producing industries [20, 21]. Occupational and environmental exposure to Cr(VI)-containing compounds is known to be toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic to human beings and diverse animals [22–24], leading to serious damage to the kidneys [25, 26], liver [27, 28], lungs [29, 30], skin [31], and other vital organs [32–34].

Cr(VI) is generally considered to be the toxic form, which can efficiently penetrate anionic channels in cellular membranes [35]. Inside cells, Cr(VI) is reduced through reactive intermediates Cr(V), Cr(IV), and to the more stable Cr(III) by cellular reductants such as glutathione, cysteine, ascorbic acid, and riboflavin and NADPH-dependent flavoenzymes [36]. In fact, the redox couples Cr(VI)/(V), Cr(V)/(IV), and Cr(III)/(II) have been shown to serve as cyclical electron donors in a Fenton-like reaction, which generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to genomic DNA damage and oxidative deterioration of lipids and proteins [37].

Liver is an organ capable of being injured by Cr(VI), and it has been demonstrated that the exposition to K2Cr2O7 induces hepatotoxicity associated to increased ROS levels [38], lipid peroxidation [39, 40], inhibition of antioxidant enzymes [41, 42], structural tissue injury [43, 44], and mitochondrial damage [45] including impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics [46, 47]. Natural and synthetic antioxidants have been reported to ameliorate or prevent K2Cr2O7-induced hepatotoxicity [42, 48, 49]. In this context, Molina-Jijón et al. [50] have recently shown that curcumin pretreatment has a protective role in K2Cr2O7-induced nephrotoxicity, and Chandra et al. [51] demonstrated protective effects of curcumin against K2Cr2O7 in male reproductive system. However, to our knowledge, the potential antihepatotoxic protective effect of curcumin on K2Cr2O7-induced hepatotoxicity has not been explored. The purpose of this study was to explore the potential protective effect of curcumin pretreatment against the K2Cr2O7-induced hepatotoxicity, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Antibodies

Curcumin, K2Cr2O7, bovine serum albumin, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), 1-methyl-2-phenylindole, tetramethoxypropane, streptomycin sulfate, guanidine hydrochloride, 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH), xanthine, xanthine oxidase, nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), glutathione reduced form (GSH), glutathione oxidized form (GSSG), GR, GST, 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced form (NADPH), N-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), potassium succinate, rotenone, sodium glutamate, sodium malate, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), decylubiquinone, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced form (NADH), ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), potassium cyanide (KCN), antimycin A, safranin O, sucrose, and paraformaldehyde were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Commercial kits to measure alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) were from ELITechGroup (Sées, France). Monochlorobimane was purchased from Fluka (Schnelldorf, Germany). Potassium phosphate monobasic (KH2PO4), sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4), trichloroacetic acid (TCA), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), methanol, high-performance liquid chromatography- (HPLC-) grade acetonitrile, and ethyl acetate were acquired from J. T. Baker (Xalostoc, Edo. Mex, México). Tris, acrylamide and bis N,N′ methylene bis acrylamide were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA). Lauryl sulfate sodium salt (SDS) and calcium chloride were acquired from Research Organics, Inc. (Cleveland, OH, USA). Arsenazo III was purchased from ICN Biomedicals Inc. (Aurora, OH, USA). Aminoacetic acid was obtained from Química Meyer (Mexico, DF, Mexico). Cyclosporine A (CsA) was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY, USA). Anti-cytochrome c [7H8.2C12] (ab13575) antibody was acquired from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT) 1/2 (N-19) (sc-9299) and rabbit anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP, sc-358914) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). All other reagents and chemicals used were of the highest grade of purity commercially available.

2.2. Experimental Design

Male Wistar rats weighing 150–200 g were used along the study. Curcumin was suspended in 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose and was given by oral gavage a dose of 400 mg/kg [50], and K2Cr2O7 was dissolved in saline solution and given via intraperitoneal (i.p.) at a dose of 15 mg/kg [52]. Six groups of rats were studied (n = 8/group). (1) Control, injected via i.p. with isotonic saline solution. (2) Curcumin was given daily for 10 days. (3) K2Cr2O7 (24 h), rats received a single injection of K2Cr2O7 on day 10 and they were sacrificed 24 h later. (4) CUR-K2Cr2O7 (24 h), curcumin was given daily for 10 days and K2Cr2O7 was injected on day 10; rats were sacrificed 24 h later. (5) K2Cr2O7 (48 h), rats were injected with a single injection of K2Cr2O7 on day 9 and they were sacrificed 48 h later. (6) CUR-K2Cr2O7 (48 h), curcumin was administered for 10 days and K2Cr2O7 was injected on day 9; rats were sacrificed 48 h later. Animals were anesthetized and blood was obtained via abdominal aorta at room temperature on day 11. Blood plasma was separated and stored at 4°C until the activity of ALT, AST, LDH, and ALP was measured using commercial kits. Livers were dissected out, cleaned, and weighted, obtaining samples for histological analyses and for measurement of oxidative stress markers and activity of the antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT, GPx, GR, and GST. Liver samples were removed to isolate mitochondria in order to determine oxidative stress markers, activity of antioxidant enzymes, oxygen consumption and the activity of NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (respiratory complex I), mitochondrial permeability transition, and cytochrome (cyt c) release. All procedures were made to minimize animal suffering and were approved by the Local Ethical Committee (FQ/CICUAL/036/12). Experimental protocols followed the guidelines of Norma Oficial Mexicana for the use and care of laboratory animals (NOM-062-ZOO-1999) and for disposal of biological residues (NOM-087-SEMARNAT-SSA1-2002).

2.3. Histological Studies

Liver slices of 0.5 cm width were fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Thin sections of 3 μm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and were examined under light microscope Leica (Cambridge, UK) [53]. The histological profiles of seven fields 100X randomly selected per rat (3-4 rats per group) were recorded, the number of necrotic hepatocytes (shrinking cells with condensed acidophilic cytoplasm and pyknotic or fragmented nucleus), was counted (n = 500–800 hepatocytes), and the percentage of damaged cells was obtained.

2.4. Markers of Oxidative Damage and Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes in Liver Homogenates

Liver was homogenized in a Brinkmann Polytron Model PT 2000 (Westbury, NY, USA) in cold potassium phosphate buffer. The homogenates were centrifuged and the supernatant was separated to measure oxidative stress markers and the activity of antioxidant enzymes. Protein concentration was measured according to the method described by Lowry et al. [54]. The content of malondialdehyde (MDA), an important toxic byproduct of lipid peroxidation, was measured by the reaction with 1-methyl-2-phenylindole, according to Chirino et al. [55]. Protein carbonyl content, a relatively stable marker of protein oxidation by ROS, was measured by their reactivity with DNPH to form protein hydrazones, as previously described by Maldonado et al. [56]. GSH content was evaluated by following the formation of a fluorescent adduct between GSH and monochlorobimane in a reaction catalyzed by GST [57]. CAT activity was assayed by a method based on the decomposition of H2O2 by CAT contained in the samples [58]. SOD activity was assayed by measuring the inhibition of NBT reduction to formazan at 560 nm [59]. GPx activity was assayed spectrophotometrically at 340 nm in a mixture assay containing GSH, H2O2, GR, and NADPH [60]. GR activity was assayed by using GSSG as substrate and measuring the disappearance of NADPH at 340 nm [61]. GST activity was assayed in a mixture containing GSH and CDNB [62].

2.5. Studies in Isolated Mitochondria

Liver was removed from rats, washed, and minced in isolation buffer before being homogenized. Mitochondria were obtained by differential centrifugation, and the protein content was measured [63]. Markers of oxidative damage and activity of antioxidant enzymes were measured as previously described in Section 2.4. Oxygen consumption was measured using a Clark type oxygen electrode (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH, USA). State 4 respiration was evaluated in the presence of succinate plus rotenone or with sodium glutamate and sodium malate. State 3 respiration was stimulated by the addition of ADP. Respiratory control index (RCI) was calculated as the ratio state 3/state 4. Uncoupled respiration was measured by adding CCCP; phosphorylation efficiency (ADP/O ratio) was calculated from the added amount of ADP and total amount of oxygen consumed during state 3 [64]. The activity of the respiratory complex I was measured by following the decrease in absorbance due to oxidation of NADH to NAD+ at 340 nm in an assay mixture containing decylubiquinone antimycin A, KCN, and of mitochondrial protein [65]. Permeability transition pore (PTP) opening was evaluated by measuring swelling which was assessed by changes in absorbance of the suspension at 540 nm, after the addition of 50 μM Ca2+ [66]. Membrane potential dissipation was evaluated by safranin O absorbance changes at 525–575 nm; the reaction was initiated by adding 50 μM Ca2+ [67]. Ca2+ retention was determined by the arsenazo III absorbance changes at 675–685 nm, after the addition of 50 μM Ca2+ [68]. These assays were effectuated in the presence or absence of CsA. To assess cytochrome c (cyt c) release, mitochondria were incubated with 50 μM Ca2+ with or without CsA for 10 min and pelleted by centrifugation. Released cyt c in the supernatant fractions and retained cyt c in pellets were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-cyt c (1 : 2,500) as described by Zazueta et al. [69]. Adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT, 1 : 1,000) content was determined as the loading marker. Cyt c and ANT levels were determined by densitometric analysis using the Image Lite Version 3.1.4 software from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE, USA).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparisons test using Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

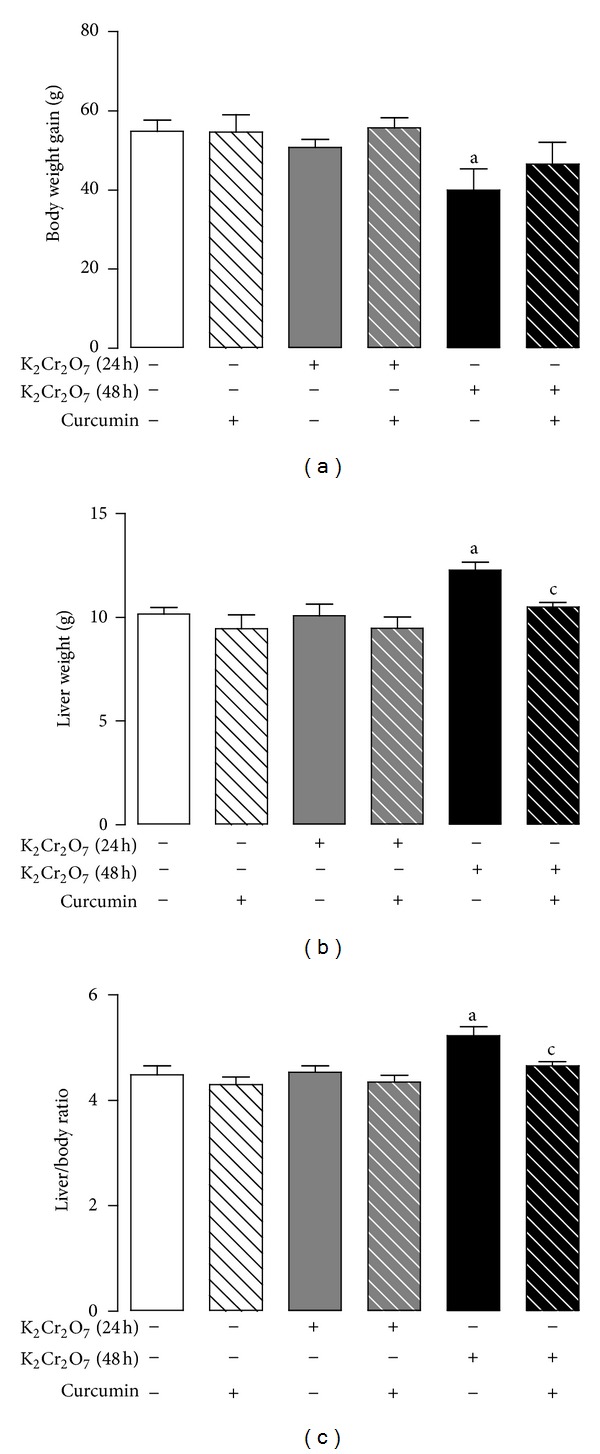

3.1. Curcumin Prevents K2Cr2O7-Induced Decrease in Body Weight Gain and Increase of Liver Weight and Liver/Body Ratio

Treatment with K2Cr2O7 resulted in a significant decrease in body weight gain and a significant increase in liver weight and liver/body ratio at 48 h (Figure 1). Pretreatment with curcumin significantly prevented these effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of curcumin on body and liver weight of rats treated with K2Cr2O7. (a) Body weight gain, (b) liver weight, and (c) liver/body ratio. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 7-8. a P < 0.05 versus control; c P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (48 h).

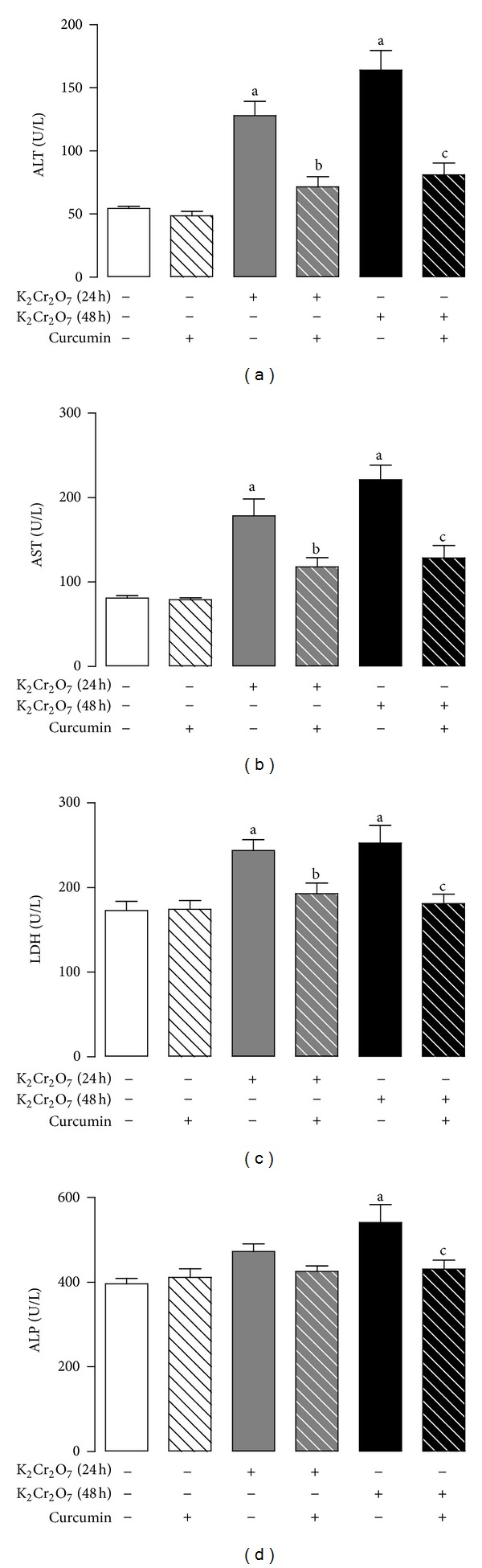

3.2. Curcumin Prevents the K2Cr2O7-Induced Increase in the Plasma Activity of ALT, AST, LDH, and ALP

Rats treated with K2Cr2O7 exhibited a significant increase in plasma AST, ALT, and LDH activities at 24 and 48 h compared to control (Figure 2). Curcumin pretreatment significantly prevented the increase in the activity of AST, ALT, and LDH (Figure 2). The K2Cr2O7-induced increase in the activity of ALP at 48 h was prevented by curcumin (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of curcumin on the activity of (a) alanine aminotransferase (ALT), (b) aspartate aminotransferase (AST), (c) lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and (d) alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in plasma of rats treated with K2Cr2O7. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 5–8. a P < 0.05 versus control; b P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (24 h);c P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (48 h).

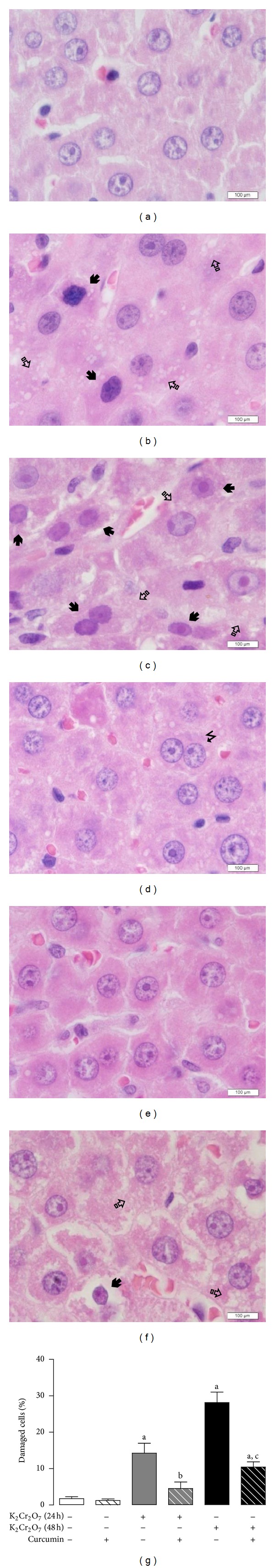

3.3. Curcumin Prevents the K2Cr2O7-Induced Histological Damage

Control and curcumin-treated groups presented normal hepatic structure, characterized by polygonal-shape hepatocytes with well-defined boundaries, slight staining acidophilic cytoplasm with large and centrally located nucleus with dispersed chromatin; some binucleated cells were also observed (Figures 3(a) and 3(d)). Treatment with K2Cr2O7 generated focal centrolobular hepatocytes death 24 h and 48 h, in a time-dependent fashion (Figures 3(b) and 3(c)); these cells showed extensive cytoplasmic vacuolation with pyknotic nucleus. In contrast, curcumin-pretreated groups showed almost normal histology; only the CUR-K2Cr2O7 group at 48 h presented occasional injured hepatocytes (Figures 3(e) and 3(f)). These features were confirmed by the quantification of damaged hepatocytes, which revealed that curcumin pretreatment prevented the K2Cr2O7-induced significant increase in hepatocytes damage at 24 and 48 h of about 15% and 30%, respectively (Figure 3(g)).

Figure 3.

Representative histopathology in rats treated with curcumin, K2Cr2O7—or both. (a) Control animal that received only the vehicle show normal hepatic architecture. (b) Rat liver section after one day or two days (c) of K2Cr2O7 administration; there are injured hepatocytes with nuclear condensation (pyknosis) and cytoplasmic vacuolization (arrows), as well as regenerative binucleated hepatocytes. (d) In contrast, administration of curcumin alone did not produce histological damage. (e) Rat treated with curcumin after one day of K2Cr2O7 administration shows normal liver histology. (f) Liver section after two days of K2Cr2O7 administration in animal pretreated with curcumin exhibited mild cytoplasmic vacuolation without pyknosis and binucleated regenerative hepatocytes (all micrographs H/E, magnification 1000X). (g) Quantitative morphometry shows significant liver protection in groups pretreated with curcumin. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 3-4. a P < 0.05 versus control; b P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (24 h); c P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (48 h).

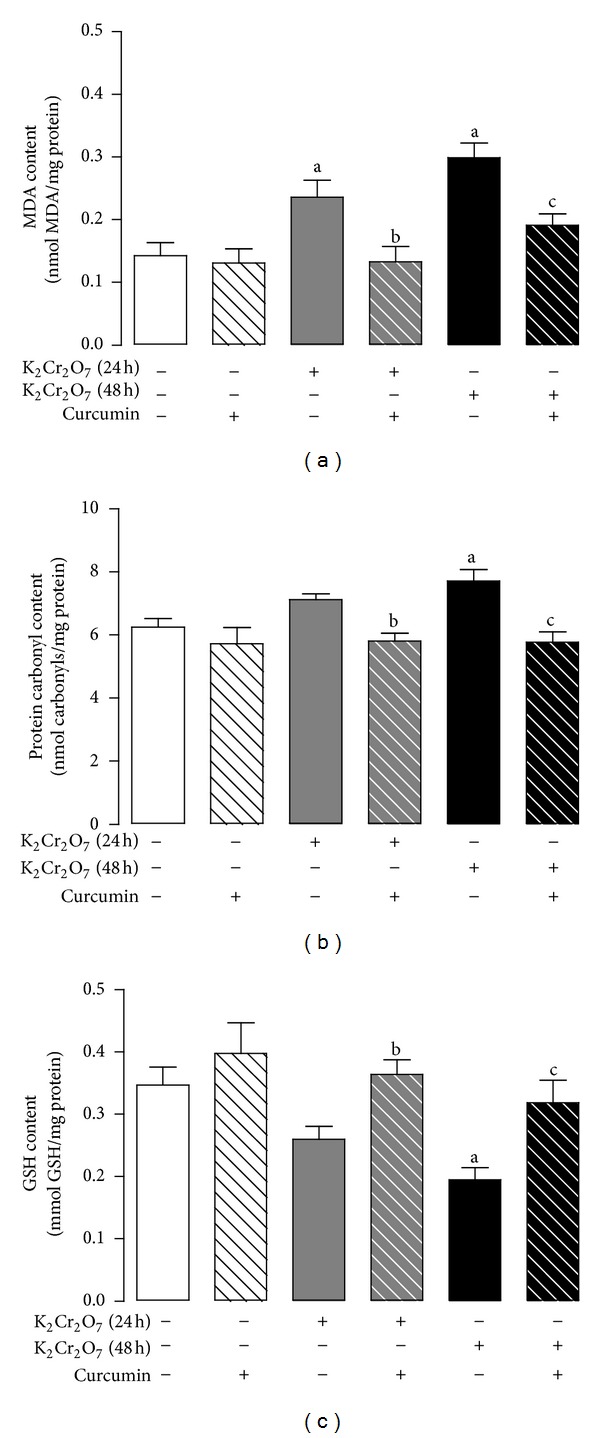

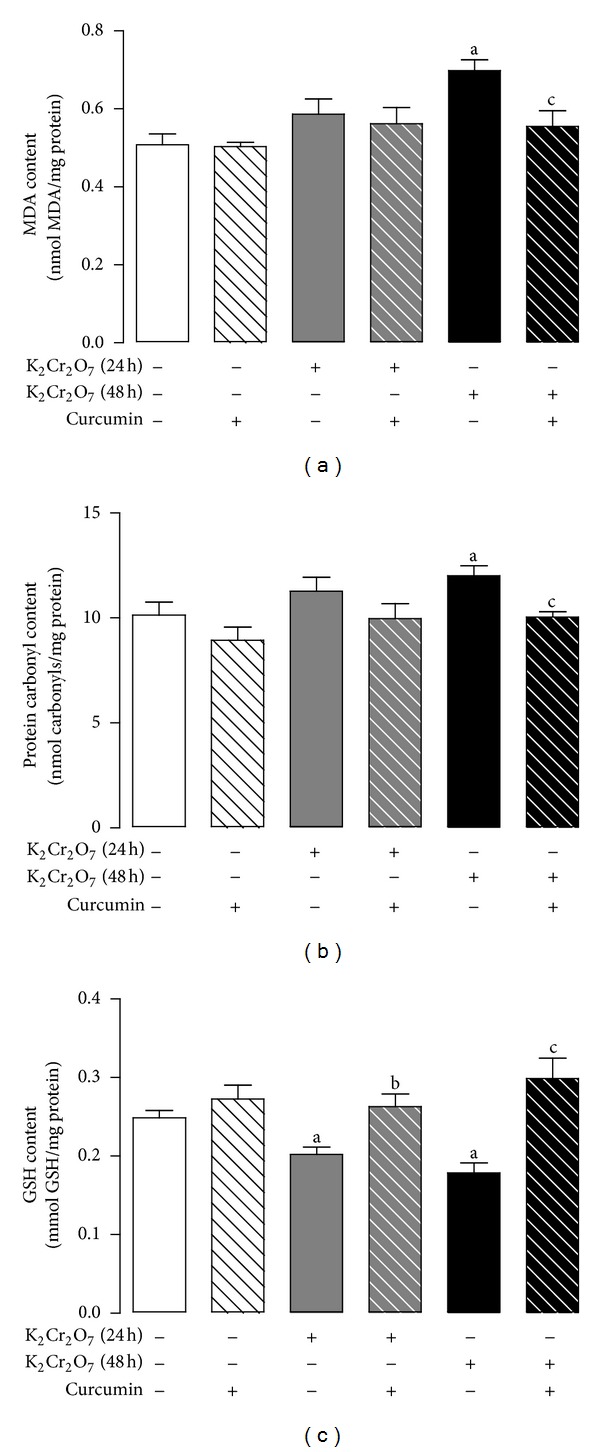

3.4. Curcumin Ameliorates K2Cr2O7-Induced Liver Oxidative Damage

Curcumin pretreatment prevents the K2Cr2O7-induced oxidative damage, which was made evident by the increase in the levels of MDA and protein carbonyl and a decrease in the levels of GSH at 48 h (Figure 4). In addition, K2Cr2O7 induced an increase of MDA levels at 24 h that was prevented by curcumin pretreatment (Figure 4). The K2Cr2O7-induced increase in protein carbonyl content and the decrease in GSH content at 24 h did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of curcumin on the liver content of oxidative stress markers of rats treated with K2Cr2O7. (a) MDA content, (b) protein carbonyl content, and (c) GSH content. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 5-6. a P < 0.05 versus control; b P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (24 h); c P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (48 h).

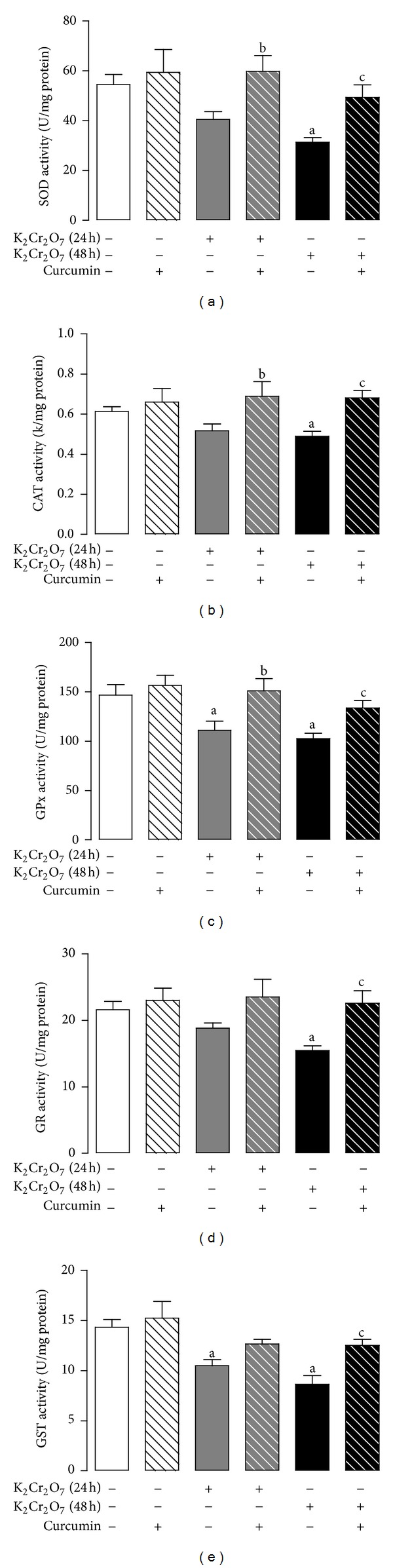

3.5. Curcumin Prevents the K2Cr2O7-Induced Decrease in the Activity of Hepatic Antioxidant Enzymes

K2Cr2O7 reduced significantly the activity of the antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT, GPx, GR, and GST at 48 h and that of GPx at 24 h that was prevented by curcumin (Figure 5). The K2Cr2O7-induced decrease in the activity of CAT and GST on 24 h was not prevented by curcumin pretreatment (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of curcumin on liver activity of antioxidant enzymes activity of rats treated with K2Cr2O7. (a) Superoxide dismutase (SOD), (b) catalase (CAT), (c) glutathione peroxidase (GPx), (d) glutathione reductase (GR), and (e) glutathione-S-transferase (GST). Values are mean ± SEM, n = 5-6. a P < 0.05 versus control; b P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (24 h); c P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (48 h).

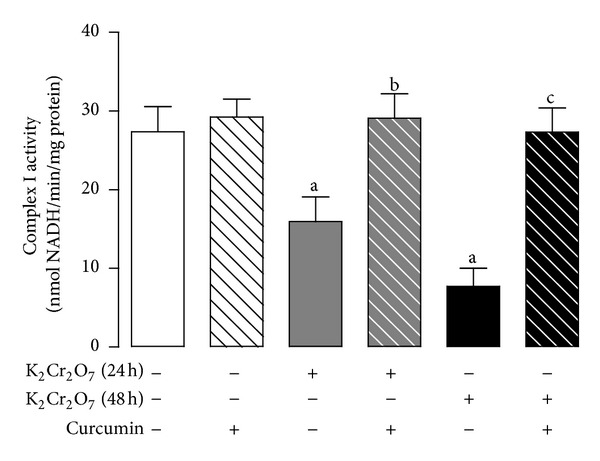

3.6. Curcumin Prevents K2Cr2O7-Induced Oxidative Damage and Decrease in the Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes in Isolated Hepatic Mitochondria

Curcumin prevented the significant increase in K2Cr2O7-induced lipid peroxidation and protein carbonyl content in hepatic mitochondria at 48 h. Besides, K2Cr2O7 produced a significant decrease of GSH content at 24 and 48 h. These changes were effectively prevented by curcumin pretreatment (Figure 6). In addition, curcumin pretreatment prevented the K2Cr2O7-induced decrease in the activity of GPx and GST at 24 h and that of SOD, CAT, GPx, GR, and GST at 48 h (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Effect of curcumin on the content of oxidative stress markers in hepatic mitochondria isolated from rats treated with K2Cr2O7. (a) MDA, (b) protein carbonyl, and (c) GSH. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 5-6. a P < 0.05 versus control; b P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (24 h); c P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (48 h).

Figure 7.

Effect of curcumin on the activity of antioxidant enzymes activity in hepatic mitochondria isolated from rats exposed to K2Cr2O7. (a) Superoxide dismutase (SOD), (b) catalase (CAT), (c) glutathione peroxidase (GPx), (d) glutathione reductase (GR), and (e) glutathione-S-transferase (GST). Values are mean ± SEM, n = 5-6. a P < 0.05 versus control; b P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (24 h); c P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (48 h).

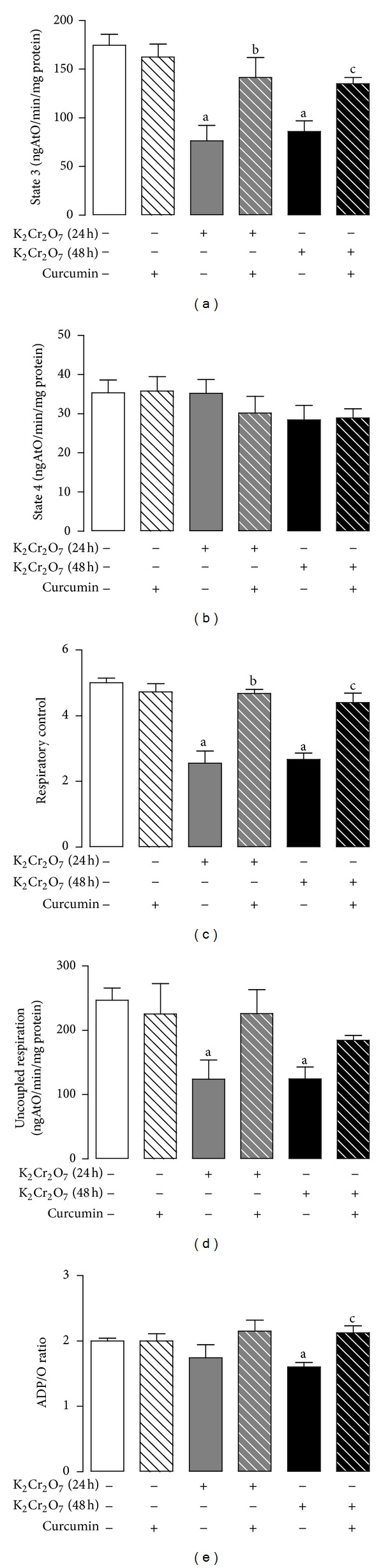

3.7. Curcumin Protects against Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induced by K2Cr2O7

Curcumin prevented the K2Cr2O7-induced decrease in mitochondrial respiration evaluated by state 3 and respiratory control index at 24 h and 48 h using malate/glutamate as substrate (Figure 8). State 4 of respiration remained unchanged in all the studied groups (Figure 8). Curcumin also prevented the K2Cr2O7-induced decrease in the ADP/O ratio at 48 h (Figure 8). The prevention by curcumin of K2Cr2O7-induced decrease in uncoupled respiration was not significative (Figure 8). The changes observed using succinate as substrate were less marked. No changes were observed at 24 h; at 48 h it was found that K2Cr2O7 induced a decrease in state 3 and in uncoupled respiration, which were not significantly prevented by curcumin (Table 1). No changes were observed in respiratory control index, ADP/O ratio, and in state 4 (Table 1). All these data led us to analyze the activity of respiratory complex I.

Figure 8.

Curcumin prevents K2Cr2O7-induced alterations in mitochondrial oxygen consumption using malate/glutamate as substrate. CUR: curcumin; RCI: respiratory control index. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 4-5. a P < 0.05 versus control; b P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (24 h); c P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (48 h).

Table 1.

Effect of curcumin pretreatment on K2Cr2O7-induced alterations in mitochondrial oxygen consumption using succinate as substrate.

| Control | CUR | K2Cr2O7 (24 h) | CUR-K2Cr2O7 (24 h) | K2Cr2O7 (48 h) | CUR-K2Cr2O7 (48 h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Succinate | ||||||

| State 3 (ngAtO/min/mg protein) | 243 ± 24 | 192 ± 9 | 169 ± 24 | 170 ± 36 | 156 ± 13a | 180 ± 27 |

| State 4 (ngAtO/min/mg protein) | 59 ± 5 | 48 ± 2 | 51 ± 7 | 40 ± 10 | 49 ± 4 | 51 ± 5 |

| RCI | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.4 |

| Uncoupled respiration (ngAtO/min/mg protein) | 396 ± 34 | 363 ± 21 | 284 ± 39 | 269 ± 63 | 245 ± 34a | 269 ± 18 |

| ADP/O | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

Values are mean ± SEM, n = 4-5. CUR: curcumin; RCI: respiratory control index. a P < 0.05 versus control.

3.8. Curcumin Prevents the K2Cr2O7-Induced Decrease in the Respiratory Complex I Activity

K2Cr2O7 induced a significative decrease in the activity of respiratory complex I at 24 h and 48 h that was effectively prevented by curcumin pretreatment (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Curcumin prevents the K2Cr2O7-induced decrease in the activity of mitochondrial complex I. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 6-7. a P < 0.05 versus control; b P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (24 h); c P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (48 h).

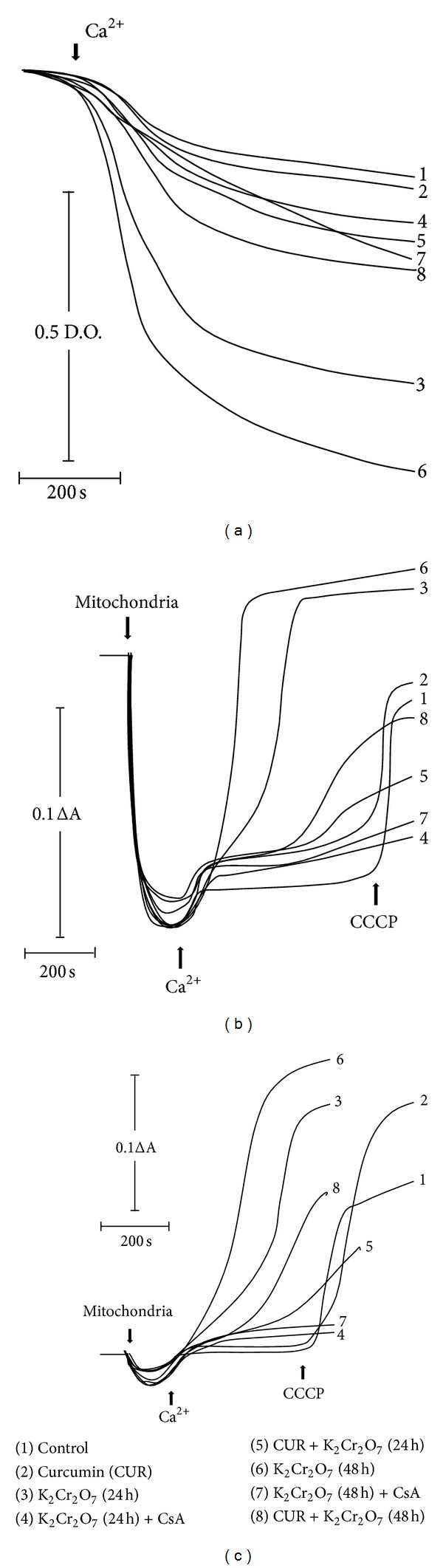

3.9. Curcumin Ameliorates the K2Cr2O7-Induced Membrane PTP Opening

Curcumin reduced the K2Cr2O7-induced mitochondrial permeability transition determined by matrix swelling, membrane potential changes, and Ca2+ retention at 24 and 48 h. Isolated mitochondria from K2Cr2O7-treated rats presented a fast and considerable swelling after adding 50 μM Ca2+ at 24 and 48 h. Curcumin pretreatment clearly avoided the K2Cr2O7-induced mitochondrial swelling (Figure 10(a)). In a similar way, K2Cr2O7 treatment sensitizes mitochondria to lose the membrane potential and the capacity of management Ca2+ by inducing PTP opening. On the contrary, curcumin pretreatment notably attenuates the K2Cr2O7-induced membrane potential collapse and Ca2+ release (Figures 10(b) and 10(c)). K2Cr2O7-induced PTP opening was prevented by CsA. Mitochondria from control or curcumin-treated rats did not present PTP opening even under conditions of Ca2+ overload until the protonophore CCCP was added.

Figure 10.

Effect of curcumin on the mitochondrial permeability transition pore-openining from rats exposed to K2Cr2O7. (a) Mitochondrial swelling, (b) mitochondrial membrane potential dissipation, and (c) mitochondrial Ca2+ retention. Tracings are representative of three different experiments. Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) was added in control and curcumin groups to induce loss of membrane potential and Ca2+ release. CUR: curcumin; CsA: cyclosporine A.

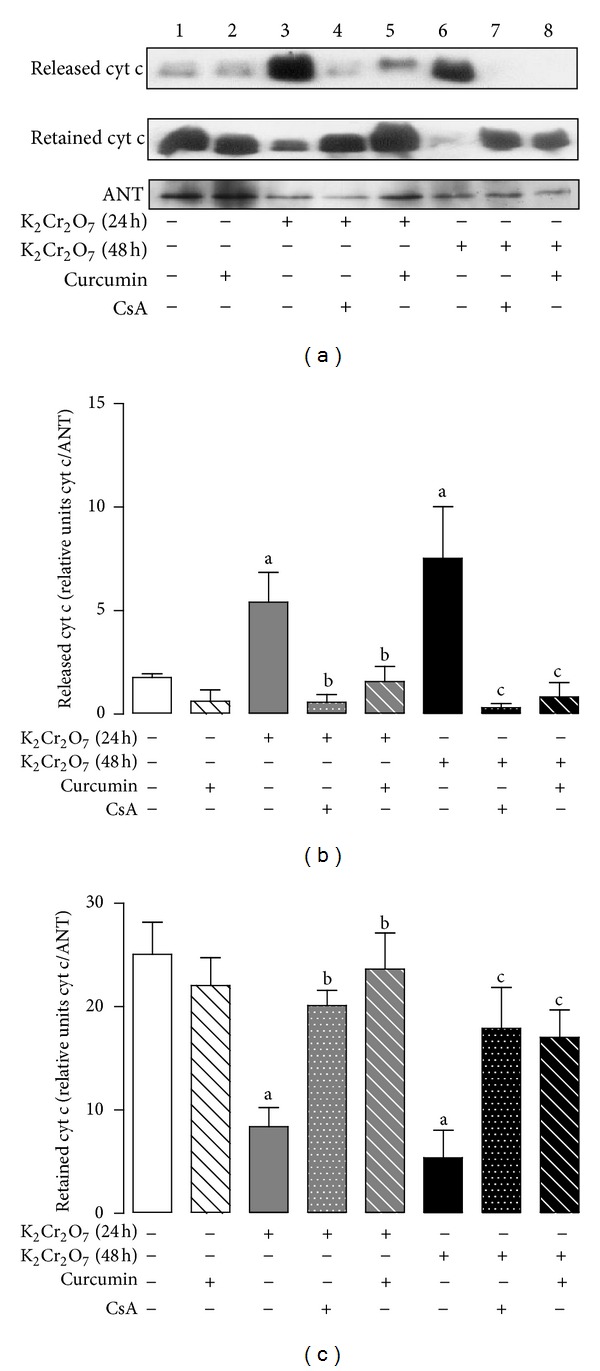

3.10. Curcumin Prevents the K2Cr2O7-Induced Cyt C Release

K2Cr2O7-induced PTP opening resulted in the release of proapoptotic factor cyt c to the cytosol at both 24 and 48 h (Figure 11(a), lanes 3 and 6). CsA abolished the K2Cr2O7-induced cyt c release (Figure 11(a), lanes 4 and 7). Interestingly, curcumin pretreatment prevents effectively the mitochondrial cyt c release that was induced by the treatment with K2Cr2O7 under conditions of Ca2+ overload (Figure 11(a), lanes 5 and 8). No effects were observed in control and curcumin groups (Figure 11(a), lanes 1 and 2). Densitometric analysis showed that released cyt c was significantly increased in mitochondria from K2Cr2O7-treated rats at 24 and 48 h. Curcumin and CsA prevented the cyt c release from mitochondria (Figure 11(b)). In contrast, retained cyt c in mitochondrial pellets from K2Cr2O7-treated rats was significantly diminished at both times while curcumin pretreatment and CsA maintained cyt c levels similar to control (Figure 11(c)). Together, these results indicate that K2Cr2O7 lowers the calcium-induced threshold for PTP opening induction and cytochrome c release.

Figure 11.

Effect of curcumin on cytochrome c (cyt c) release induced by the treatment with K2Cr2O7. Liver mitochondria were incubated for 10 min with 50 μM Ca2+, in the presence or the absence of CsA. (a) Mitochondrial cyt c released and cyt c retained by Western blot analysis, (b) cyt c released/ANT ratio, and (c) cyt c retained/ANT ratio. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 3. a P < 0.05 versus control; b P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (24 h); c P < 0.05 versus K2Cr2O7 (48 h). ANT: adenine nucleotide translocator; CsA: cyclosporine A.

4. Discussion

Experimental models of toxic liver injury are utilized to evaluate the biochemical processes involved in many forms of liver disease and to evaluate the possible pharmacological effects of candidate hepatoprotectants like curcumin [4].

Our data clearly show that curcumin pretreatment effectively prevented K2Cr2O7-induced hepatotoxicity. This protective effect was associated to the prevention of K2Cr2O7-induced oxidative damage, decrease in the activity of antioxidant enzymes in both liver homogenates and isolated mitochondria, and impairment in mitochondrial oxygen consumption, respiratory complex I inhibition, and PTP opening. The K2Cr2O7-induced hepatotoxicity was evident by the decrease in body weight gain, liver weight, and liver/body ratio, the increase in the plasma activity of ALT, AST, LDH, and ALP, and by the histopathological alterations. Kumar and Roy [70] also found that chromium induced a decrease in body weight gain, liver weight, and liver/body ratio. Increased plasma activity of ALT, AST, and ALP is indicative of hepatocellular damage since the disruption of the plasma membrane leak intracellular enzymes into the bloodstream [71, 72]. Treatment with K2Cr2O7 significantly augmented the activity of these enzymes in a time-dependent fashion. LDH in plasma is a presumptive marker of necrotic lesions in the hepatocytes [73]. Pretreatment with curcumin prevented the increase in the above-mentioned alterations, demonstrating the hepatoprotective effect of curcumin against the K2Cr2O7-induced damage. These findings are compatible with the results of other studies using curcumin against iron-induced hepatic toxicity [74] or thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis [75]. Histopathological abnormalities were observed in liver of rats treated with K2Cr2O7 in a time-dependent fashion that correspond with the increase in the activity of plasma enzymes. The redox alterations caused by oxidative agents like Cr(VI) compounds have been shown to induce apoptosis and necrosis in hepatocytes and other cells [76]. In this way, the antioxidant curcumin prevented the K2Cr2O7-induced structural injury, preserving the normal architecture in liver tissue and saving hepatocytes from ROS. Previous studies have shown that curcumin protects against liver histological changes induced by toxins as carbon tetrachloride [17], acetaminophen [77], or cypermethrin [78]. Liver, the primary organ involved in the xenobiotic metabolism, is particularly susceptible to injury, and many reports suggest that chromium is a hepatotoxin [79–82]. Chromium induced-hepatotoxicity may be attenuated by several compounds [83–85]. The antihepatotoxic effects of curcumin against liver injury are well recognized and attributed to its intrinsic antioxidant properties [86–88].

Cr(VI) induces oxidative stress through enhanced ROS production leading to genomic DNA damage and oxidative deterioration of lipids and proteins. ROS include superoxide anion radical O2 •−, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (•OH) [20]. Lipid peroxidation generates a wide variety of end products, including MDA, which is used as a marker of oxidative damage. MDA may damage membrane proteins and lipids [89]. However, the formation of oxidized proteins is one of the highlights of oxidative stress, and the carbonyl groups (aldehydes and ketones) are produced on protein side chains when they are oxidized [90]. The results obtained show clearly that K2Cr2O7 increased lipid peroxidation and oxidized proteins reflecting hepatic oxidative damage. Curcumin pretreatment could prevent K2Cr2O7-induced oxidative damage because it is considered a bifunctional antioxidant exerting direct effects by scavenging •OH, O2 •−, and peroxyl radicals [91] and indirect effects inducing the expression of antioxidant enzymes [92].

GSH is a tripeptide (L-γ-glutamyl-L-cysteinylglycine) responsible for protection against ROS and other reactive species and detoxification of endogenous and exogenous toxins of an electrophilic nature [93]. Depletion of GSH decreases the antioxidant capacity and leads to oxidative stress [94, 95]. Rats treated with K2Cr2O7 presented low GSH levels in comparison with control, probably due to the oxidative stress induced for the K2Cr2O7 exposition. Soudani et al. [42] stated that this reduction in GSH levels might be due to its consumption in the scavenging of free radicals generated by K2Cr2O7. Curcumin pretreatment restored GSH levels, in a similar way to previous reports demonstrating the effectiveness curcumin in the reestablishment of the GSH content in the liver of rats exposed to paracetamol [14] or aflatoxin [96].

Antioxidant enzymes are important protective mechanisms against ROS. SOD catalyses the dismutation of O2 •− to O2 and to the less reactive species H2O2. Peroxides can be degraded by CAT or GPx [97]. GR converts GSSG to GSH by using NADPH whereas GST catalyzes the conjugation of electrophilic species with GSH [98]. In this study, K2Cr2O7 decreased the activity of SOD, CAT, GPx, GR, and GST mainly 48 h after treatment. This effect may be secondary to decreased enzyme levels (secondary to changes in synthesis or degradation of enzymes) or decreased activity (e.g., by oxidative damage) without changes in enzymes levels [95]. In this context, Kalayarasan et al. [73] postulated that K2Cr2O7 produces high levels of O2 •− which override enzymatic activity in liver tissues. Pretreatment with curcumin reestablished the activity of antioxidant enzymes to normal in animals exposed to K2Cr2O7, as has been shown in different curcumin hepatoprotection studies against sodium arsenite [99], acrylonitrile [100], chloroquine [101], or arsenic trioxide [102] toxicity. Besides, Iqbal et al. [5] revealed that curcumin administration increases several cytoprotective enzymes, especially in the liver.

Hepatocytes are normally rich in mitochondria, and each hepatocyte contains about 800 mitochondria occupying about 18% of the entire liver cell volume [103]. Mitochondria are targets of metal toxicity, and in many cases is related with oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction [104–107]. Mitochondria are the main intracellular source of ROS as byproducts of the consumption of molecular oxygen in the electron transport chain and themselves are susceptible to oxidation; however, they possess a very effective antioxidant system [108, 109]. The experimental results in hepatic mitochondria isolated from rats treated with K2Cr2O7 demonstrate an increase in mitochondrial lipids and oxidized proteins, GSH depletion and reduction in the activity of antioxidant enzymes being this effect more consistent after 48 h of exposition. These results are in relation with previous studies [110, 111]. Moreover, curcumin successfully prevents mitochondrial oxidative damage and the alterations in the antioxidant enzyme activities caused by K2Cr2O7. Curcumin can protect rat liver mitochondria from ROS-induced lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation by donating H-atoms from its phenolic and methylenic groups of the β-diketone moiety [86, 112], augmenting levels of GSH [113, 114] or increasing the cytoprotective defenses, in a similar way with other experimental models [115, 116].

Oxidative stress leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, decrease in oxygen consumption and ATP production, alterations in calcium homeostasis, oxidation of DNA, proteins, and lipids, PTP opening, modifying of the expression of antioxidant enzymes and enhancing expression, and/or DNA binding of numerous transcription factors [117–119]. Our results showed that liver mitochondria isolated from rats exposed to K2Cr2O7 presented alterations in oxygen consumption by decreasing state 3 respiration, RCI, uncoupled respiration and ADP/O ratio using malate/glutamate. Negative effects using succinate were less evident, affecting state 3 and uncoupled respiration. These results indicate that K2Cr2O7 could damage biomolecules from the electron transport chain, especially complex I. In agreement, Cr(VI) has shown noxious effects on liver mitochondrial bioenergetics, as a consequence of its oxidizing activity which shunts electrons from electron donors coupled to ATP production, and to the ability of Cr(III), derived from Cr(VI) reduction, to form stable complexes with ATP precursors and enzymes involved in the ATP synthesis [46]. Noticeably, pretreatment with curcumin restored oxygen consumption supporting state 3 respiration, RCI, uncoupled respiration, and ADP/O ratio, suggesting well-coupled mitochondria. Curcumin prevents mitochondrial dysfunction by maintaining redox homeostasis or by protecting the mitochondrial respiratory complex [120, 121].

The mitochondrial respiratory chain is one of the major sources of damaging free radicals in human organism, and unpaired electrons escaping from the respiratory complexes (mainly from complexes I and III) can lead to the formation of O2 •− by the interaction with O2 [122]. Mitochondrial complex I is a large enzyme complex of over 40 subunits embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane and has a central role in energy production by the mitochondrial respiratory chain, providing about 40% of the proton-motive force required for the synthesis of ATP [123]. Complex I dysfunction is the most common mitochondrial defect leading to cell death and disease [124]. The present findings show that K2Cr2O7 inhibited complex I activity in a time-dependent mode. Fernandes et al. [47] showed that in rat liver mitochondria complex I was more sensitive to Cr(VI) than complex II, and the activity of cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) was not affected. Instead, curcumin pretreatment preserved the complex I activity possibly because curcumin scavenges ROS or reduces ROS production in complex I. Recently, it has been reported that curcumin attenuates the inhibition of mitochondrial complex I in K2Cr2O7-induced nephrotoxicity [50], peroxynitrite-induced neurotoxicity [125], or catecholamine-induced cardiotoxicity [126].

The transfer of electrons along the respiratory chain generates an electrochemical gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane comprising both a membrane potential and H+ gradient [127]. In order to maintain those gradients, it is essential that the inner membrane of mitochondria remains impermeable or selectively permeable to metabolites and ions under normal aerobic conditions. However, in response to stress, the permeability of the mitochondrial membrane may increase, with the formation of a voltage-dependent nonspecific pore in the inner membrane known as the mitochondrial PTP [128]. PTP opening causes massive swelling of mitochondria, membrane depolarization, calcium release, rupture of the outer membrane, and release of intermembrane components that induce apoptosis [129]. Thus, the results confirmed that mitochondria from livers of K2Cr2O7-treated rats presented PTP opening and cyt c release, as previously described by Xiao et al. [130]. in L-02 hepatocyte and Pritchard et al. [131] in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Curcumin pretreatment ameliorates the mitochondrial PTP opening from K2Cr2O7-treated rats protecting them from the noxious effects generated from Cr(VI). Besides, curcumin presents antihepatotoxic effects against ethanol-induced cytochrome c translocation in cultures of isolated rat hepatocytes [132], induces protective effects against catecholamine-induced cardiotoxicity by preserving mitochondrial function [126], and prevents mitochondrial dysfunction in an aging model [133].

Antihepatotoxic effects of curcumin were able to inhibit the PTP opening, and this outcome was related to its antioxidant properties by suppressing both O2 •− production and lipid peroxidation [134]. In contrast, antihepatocarcinogenic effects of curcumin induces the apoptosis of tumor cells through mitochondria-dependant pathways, including the release of cyt c, changes in electron transport, and loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential as has been described in human hepatocellular carcinoma J5 cells [135, 136], and HepG2 cells [137, 138], by its potent antioxidant as well as anti-inflammatory properties [139]. Thus, curcumin has a dual effect inducing PTP opening.

In summary, acute K2Cr2O7-exposure enhances the oxidative stress both by mitochondrial dysfunction as well as due to the failure in the ROS removal system that in turn causes liver injury. Curcumin pretreatment successfully attenuated hepatic damage and prevented oxidative stress and the decrease in the activity of antioxidant enzymes in both liver homogenates and isolated mitochondria. Also, curcumin ameliorated respiratory complex I activity and avoided PTP opening. All these beneficial effects of curcumin protected liver from K2Cr2O7-induced hepatotoxicity associated with mitochondrial dysfunction.

Conflict of Interests

The authors do not have any conflict of interests with the content of the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PAPIIT (Grants nos. IN201910 and IN210713) and CONACYT (Grants nos. 167949, 177527, 129838, and 204474).

References

- 1.Anand P, Sundaram C, Jhurani S, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin and cancer: an “old-age” disease with an “age-old” solution. Cancer Letters. 2008;267(1):133–164. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chattopadhyay I, Biswas K, Bandyopadhyay U, Banerjee RK. Turmeric and curcumin: biological actions and medicinal applications. Current Science. 2004;87(1):44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aggarwal B, Bhatt I, Ichikawa H, et al. Turmeric: the Genus Curcuma, Medicinal and Aromatic Plants-Industrial Profiles. New York, NY, USA: CRC Press; 2007. Curcumin—biological and medicinal properties; pp. 297–368. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivera-Espinoza Y, Muriel P. Pharmacological actions of curcumin in liver diseases or damage. Liver International. 2009;29(10):1457–1466. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iqbal M, Sharma SD, Okazaki Y, Fujisawa M, Okada S. Dietary supplementation of curcumin enhances antioxidant and phase II metabolizing enzymes in ddY male mice: possible role in protection against chemical carcinogenesis and toxicity. Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2003;92(1):33–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.920106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tajbakhsh S, Mohammadi K, Deilami I, et al. Antibacterial activity of indium curcumin and indium diacetylcurcumin. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2008;7(21):3832–3835. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jurenka JS. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of Curcuma longa: a review of preclinical and clinical research. Alternative Medicine Review. 2009;14(2):141–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggarwal BB, Kumar A, Bharti AC. Anticancer potential of curcumin: preclinical and clinical studies. Anticancer Research. 2003;23(1):363–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farombi EO, Shrotriya S, Na H-K, Kim S-H, Surh Y-J. Curcumin attenuates dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver injury in rats through Nrf2-mediated induction of heme oxygenase-1. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46(4):1279–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nanji AA, Jokelainen K, Tipoe GL, Rahemtulla A, Thomas P, Dannenberg AJ. Curcumin prevents alcohol-induced liver disease in rats by inhibiting the expression of NF-κB-dependent genes. American Journal of Physiology. 2003;284(2):G321–G327. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00230.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathuria N, Verma RJ. Curcumin ameliorates aflatoxin-induced lipid peroxidation in liver, kidney and testis of mice—an in vitro study. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica. 2007;64(5):413–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yousef MI, Omar SAM, El-Guendi MI, Abdelmegid LA. Potential protective effects of quercetin and curcumin on paracetamol-induced histological changes, oxidative stress, impaired liver and kidney functions and haematotoxicity in rat. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2010;48(11):3246–3261. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hemeida RAM, Mohafez OM. Curcumin attenuates methotraxate-induced hepatic oxidative damage in rats. Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute. 2008;20(2):141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farghaly HS, Hussein MA. Protective effect of curcumin against paracetamol-induced liver damage. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 2010;4(9):4266–4274. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng S, Yumei F, Chen A. De novo synthesis of glutathione is a prerequisite for curcumin to inhibit hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2007;43(3):444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Priya S, Sudhakaran PR. Curcumin-induced recovery from hepatic injury involves induction of apoptosis of activated hepatic stellate cells. Indian Journal of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2008;45(5):317–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu Y, Zheng S, Lin J, Ryerse J, Chen A. Curcumin protects the rat liver from CCl4-caused injury and fibrogenesis by attenuating oxidative stress and suppressing inflammation. Molecular Pharmacology. 2008;73(2):399–409. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.039818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subudhi U, Das K, Paital B, Bhanja S, Chainy GBN. Alleviation of enhanced oxidative stress and oxygen consumption of l-thyroxine induced hyperthyroid rat liver mitochondria by vitamin E and curcumin. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2008;173(2):105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pechova A, Pavlata L. Chromium as an essential nutrient: a review. Veterinarni Medicina. 2007;52(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagchi D, Stohs SJ, Downs BW, Bagchi M, Preuss HG. Cytotoxicity and oxidative mechanisms of different forms of chromium. Toxicology. 2002;180(1):5–22. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00378-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He X, Lin GX, Chen MG, Zhang JX, Ma Q. Protection against chromium (VI)-Induced oxidative stress and apoptosis by Nrf2. Recruiting Nrf2 into the nucleus and disrupting the nuclear Nrf2/Keap1 Association. Toxicological Sciences. 2007;98(1):298–309. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armienta MA, Morton O, Rodríguez R, Cruz O, Aguayo A, Ceniceros N. Chromium in a tannery wastewater irrigated area, León Valley, Mexico. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2001;66(2):189–195. doi: 10.1007/s0012800224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pawlikowski M, Szalińska E, Wardas M, Dominik J. Chromium originating from tanneries in river sediments: a preliminary investigation from the upper Dunajec River (Poland) Polish Journal of Environmental Studies. 2006;15(6):885–894. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton-Bermea O, Hernández-Álvarez E, Lozano R, Guzmán-Morales J, Martínez G. Spatial distribution of heavy metals in top soils around the industrial facilities of Cromatos de México, Tultitlan Mexico. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2010;85(5):520–524. doi: 10.1007/s00128-010-0124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedraza-Chaverrí J, Barrera D, Medina-Campos ON, et al. Time course study of oxidative and nitrosative stress and antioxidant enzymes in K2Cr2O7-induced nephrotoxicity. BMC Nephrology. 2005;6, article 4 doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linos A, Petralias A, Christophi CA, et al. Oral ingestion of hexavalent chromium through drinking water and cancer mortality in an industrial area of Greece—an ecological study. Environmental Health. 2011;10(1, article 50) doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stift A, Friedl J, Längle F, Berlakovich G, Steininger R, Mühlbacher F. Successful treatment of a patient suffering from severe acute potassium dichromate poisoning with liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;69(11):2454–2455. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200006150-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rafael AI, Almeida A, Santos P, et al. A role for transforming growth factor-β apoptotic signaling pathway in liver injury induced by ingestion of water contaminated with high levels of Cr(VI) Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2007;224(2):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witmer C, Faria E, Park HS, et al. In vivo effects of chromium. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1994;102(3):169–176. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aw T-C. Clinical and epidemiological data on lung cancer at a chromate plant. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 1997;26(1):S8–S12. doi: 10.1006/rtph.1997.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin C-C, Wu M-L, Yang C-C, Ger J, Tsai W-J, Deng J-F. Acute severe chromium poisoning after dermal exposure to hexavalent chromium. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 2009;72(4):219–221. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shrivastava R, Upreti RK, Seth PK, Chaturvedi UC. Effects of chromium on the immune system. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2002;34(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nudler SI, Quinteros FA, Miler EA, Cabilla JP, Ronchetti SA, Duvilanski BH. Chromium VI administration induces oxidative stress in hypothalamus and anterior pituitary gland from male rats. Toxicology Letters. 2009;185(3):187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gatto NM, Kelsh MA, Mai DH, Suh M, Proctor DM. Occupational exposure to hexavalent chromium and cancers of the gastrointestinal tract: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiology. 2010;34(4):388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henkler F, Brinkmann J, Luch A. The role of oxidative stress in carcinogenesis induced by metals and xenobiotics. Cancers. 2010;2(2):376–396. doi: 10.3390/cancers2020376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ueno S, Kashimoto T, Susa N, et al. Detection of dichromate (VI)-induced DNA strand breaks and formation of paramagnetic chromium in multiple mouse organs. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2001;170(1):56–62. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bagchi D, Bagchi M, Stohs SJ. Chromium (VI)-induced oxidative stress, apoptotic cell death and modulation of p53 tumor suppressor gene. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2001;222(1-2):149–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patlolla AK, Barnes C, Yedjou C, Velma VR, Tchounwou PB. Oxidative stress, DNA damage, and antioxidant enzyme activity induced by hexavalent chromium in sprague-dawley rats. Environmental Toxicology. 2009;24(1):66–73. doi: 10.1002/tox.20395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bagchi D, Hassoun EA, Bagchi M, Muldoon DF, Stohs SJ. Oxidative stress induced by chronic administration of sodium dichromate [Cr(VI)] to rats. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C. 1995;110(3):281–287. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(94)00103-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu KJ, Shi X. In vivo reduction of chromium (VI) and its related free radical generation. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2001;222(1-2):41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ueno S, Susa N, Furukawa Y, Aikawa K, Itagaki I. Cellular injury and lipid peroxidation induced by hexavalent chromium in isolated rat hepatocytes. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi. 1989;51(1):137–145. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.51.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soudani N, Ben Amara I, Sefi M, Boudawara T, Zeghal N. Effects of selenium on chromium (VI)-induced hepatotoxicity in adult rats. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 2011;63(6):541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woźniak F, Borzecki Z, Swies Z. Histopathologic and histochemical examination of rat liver after prolonged experimental application of potassium bichromate. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Sklodowska. Sectio D. 1991;46:65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Acharya S, Mehta K, Krishnan S, Rao CV. A subtoxic interactive toxicity study of ethanol and chromium in male Wistar rats. Alcohol. 2001;23(2):99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pourahmad J, Mihajlovic A, O’Brien PJ. Hepatocyte lysis induced by environmental metal toxins may involve apoptotic death signals initiated by mitochondrial injury. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2001;500:249–252. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0667-6_38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryberg D, Alexander J. Inhibitory action of hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) on the mitochondrial respiration and a possible coupling to the reduction of Cr(VI) Biochemical Pharmacology. 1984;33(15):2461–2466. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90718-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fernandes MAS, Santos MS, Alpoim MC, Madeira VMC, Vicente JAF. Chromium(VI) interaction with plant and animal mitochondrial bioenergetics: a comparative study. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology. 2002;16(2):53–63. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chorvatovicova D, Kovacikova Z, Sandula J, Navarova J. Protective effect of sulfoethylglucan against hexavalent chromium. Mutation Research. 1993;302(4):207–211. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(93)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Susa N, Ueno S, Furukawa Y, Ueda J, Sugiyama M. Potent protective effect of melatonin on chromium(VI)-induced DNA single-strand breaks, cytotoxicity, and lipid peroxidation in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1997;144(2):377–384. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Molina-Jijón E, Tapia E, Zazueta C, et al. Curcumin prevents Cr(VI)-induced renal oxidant damage by a mitochondrial pathway. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2011;51(8):1543–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chandra AK, Chatterjee A, Ghosh R, Sarkar M. Effect of curcumin on chromium-induced oxidative damage in male reproductive system. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2007;24(2):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim E, Na KJ. Nephrotoxicity of sodium dichromate depending on the route of administration. Archives of Toxicology. 1991;65(7):537–541. doi: 10.1007/BF01973713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coballase-Urrutia E, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Cárdenas-Rodríguez N, et al. Hepatoprotective effect of acetonic and methanolic extracts of Heterotheca inuloides against CCl4-induced toxicity in rats. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 2011;63(4):363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1951;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chirino YI, Sánchez-González DJ, Martínez-Martínez CM, Cruz C, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Protective effects of apocynin against cisplatin-induced oxidative stress and nephrotoxicity. Toxicology. 2008;245(1-2):18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maldonado PD, Barrera D, Rivero I, et al. Antioxidant S-allylcysteine prevents gentamicin-induced oxidative stress and renal damage. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2003;35(3):317–324. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chirino Y, Sánchez-Pérez Y, Osornio-Vargas A, et al. PM(10) impairs the antioxidant defense system and exacerbates oxidative stress driven cell death. Toxicology Letters. 2010;193:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barrera D, Maldonado PD, Medina-Campos ON, Hernández-Pando R, Ibarra-Rubio ME, Pedraza-Chaverrí J. Protective effect of SnCl2 on K2Cr2O7-induced nephrotoxicity in rats: the indispensability of HO-1 preinduction and lack of association with some antioxidant enzymes. Life Sciences. 2003;73(23):3027–3041. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pedraza-Chaverrí J, Maldonado PD, Medina-Campos ON, et al. Garlic ameliorates gentamicin nephrotoxicity: relation to antioxidant enzymes. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2000;29(7):602–611. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Orozco-Ibarra M, Medina-Campos O, Sánchez-González D, et al. Evaluation of oxidative stress in D-serine induced nephrotoxicity. Toxicology. 2007;229:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pedraza-Chaverrí J, González-Orozco AE, Maldonado PD, Barrera D, Medina-Campos ON, Hernández-Pando R. Diallyl disulfide ameliorates gentamicin-induced oxidative stress and nephropathy in rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;473(1):71–78. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01948-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pedraza-Chaverri J, Yam-Canul P, Chirino YI, et al. Protective effects of garlic powder against potassium dichromate-induced oxidative stress and nephrotoxicity. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46(2):619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tapia E, Soto V, Ortiz-Vega KM, et al. Curcumin induces Nrf2 nuclear translocation and prevents glomerular hypertension, hyperfiltration, oxidant stress, and the decrease in antioxidant enzymes in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2012;2012:14 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/269039.269039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Correa F, García N, Robles C, Martínez-Abundis E, Zazueta C. Relationship between oxidative stress and mitochondrial function in the post-conditioned heart. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2008;40(6):599–606. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zúñiga-Toalá A, Tapia E, Zazueta C, et al. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid pretreatment prevents ischemia and reperfusion induced renal injury, oxidant stress and mitochondrial alterations. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2012;6:2938–2947. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Correa F, Soto V, Zazueta C. Mitochondrial permeability transition relevance for apoptotic triggering in the post-ischemic heart. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2007;39(4):787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.García N, Zazueta C, Carrillo R, Correa F, Chávez E. Copper sensitizes the mitochondrial permeability transition to carboxytractyloside and oleate. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2000;209(1-2):119–123. doi: 10.1023/a:1007151511817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zazueta C, García N, Martínez-Abundis E, Pavón N, Hernández-Esquivel L, Chávez E. Reduced capacity of Ca2+ retention in liver as compared to kidney mitochondria. ADP requirement. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2010;42(5):381–386. doi: 10.1007/s10863-010-9300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zazueta C, Franco M, Correa F, et al. Hypothyroidism provides resistance to kidney mitochondria against the injury induced by renal ischemia-reperfusion. Life Sciences. 2007;80(14):1252–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar S, Roy S. Effect of chromium on certain aspects of cellular toxicity. Iranian Journal of Toxicology. 2009;2:260–267. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Amacher DE. Serum transaminase elevations as indicators of hepatic injury following the administration of drugs. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 1998;27(2):119–130. doi: 10.1006/rtph.1998.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hassan Z, Elobeid M, Virk P, et al. Bisphenol A induces hepatotoxicity through oxidative stress in rat model. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2012;2012:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/194829.194829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kalayarasan S, Sriram N, Sureshkumar A, Sudhandiran G. Chromium (VI)-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis is reduced by garlic and its derivative S-allylcysteine through the activation of Nrf2 in the hepatocytes of Wistar rats. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2008;28(7):908–919. doi: 10.1002/jat.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reddy ACP, Lokesh BR. Effect of curcumin and eugenol on iron-induced hepatic toxicity in rats. Toxicology. 1996;107(1):39–45. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(95)03199-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang M-E, Chen Y-C, Chen I-S, Hsieh S-C, Chen S-S, Chiu C-H. Curcumin protects against thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis by attenuating the inflammatory response and inducing apoptosis of damaged hepatocytes. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Han D, Hanawa N, Saberi B, Kaplowitz N. Mechanisms of liver injury. III. Role of glutathione redox status in liver injury. American Journal of Physiology. 2006;291(1):G1–G7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00001.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kheradpezhouh E, Panjehshahin M-R, Miri R, et al. Curcumin protects rats against acetaminophen-induced hepatorenal damages and shows synergistic activity with N-acetyl cysteine. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;628(1–3):274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sankar P, Telang AG, Manimaran A. Protective effect of curcumin on cypermethrin-induced oxidative stress in Wistar rats. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 2012;64(5):487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Von Burg R, Liu D. Chromium and hexavalent chromium. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 1993;13(3):225–230. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550130315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Costa M. Toxicity and carcinogenicity of Cr(VI) in animal models and humans. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 1997;27(5):431–442. doi: 10.3109/10408449709078442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anand SS. Protective effect of vitamin B6 in chromium-induced oxidative stress in liver. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2005;25(5):440–443. doi: 10.1002/jat.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rao MV, Parekh SS, Chawla SL. Vitamin-E supplementation ameliorates chromium-and/or nickel induced oxidative stress in vivo. Journal of Health Science. 2006;52(2):142–147. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chorvatovicova D, Ginter E, Kosinova A, Zloch Z. Effect of vitamins C and E on toxicity and mutagenicity of hexavalent chromium in rat and guinea pig. Mutation Research. 1991;262(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(91)90104-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Susa N, Ueno S, Furukawa Y. Protective effects of thiol compounds on chromate-induced toxicity in vitro and in vivo. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1994;102(3):247–250. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boşgelmez II, Söylemezoğlu T, Güvendik G. The protective and antidotal effects of taurine on hexavalent chromium-induced oxidative stress in mice liver tissue. Biological Trace Element Research. 2008;125(1):46–58. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wei Q-Y, Chen W-F, Zhou B, Yang L, Liu Z-L. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation in rat liver mitochondria by curcumin and its analogues. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1760(1):70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alp H, Aytekin I, Hatipoglu N, Alp A, Ogun M. Effects of sulforophane and curcumin on oxidative stress created by acute malathion toxicity in rats. European Review For Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2012;16:144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tokaç M, Taner G, Aydın S, et al. Protective effects of curcumin against oxidative stress parameters and DNA damage in the livers and kidneys of rats with biliary obstruction. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2013;6915:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Adly AAM. Oxidative stress and disease: an updated review. Research Journal of Immunology. 2010;3(2):129–145. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dalle-Donne I, Rossi R, Giustarini D, Milzani A, Colombo R. Protein carbonyl groups as biomarkers of oxidative stress. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2003;329(1-2):23–38. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(03)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ak T, Gülçin I. Antioxidant and radical scavenging properties of curcumin. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2008;174(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P. Direct and indirect antioxidant properties of inducers of cytoprotective proteins. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. 2008;52(1):S128–S138. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lushchak VI. Glutathione homeostasis and functions: potential targets for medical interventions. Journal of Amino Acids. 2012;2012:26 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/736837.736837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gutierrez LLP, Mazzotti NC, Araújo ASR, et al. Peripheral markers of oxidative stress in chronic mercuric chloride intoxication. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2006;39(6):767–772. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2006000600009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Whillier S, Kuchel P, Raftos J. Oxidative stress in type II diabetes mellitus and the role of the endogenous antioxidant glutathione. In: Croniger C, editor. Role of the Adipocyte in Development of Type 2 Diabetes. Croatia: InTech Europe; 2011. pp. 129–252. [Google Scholar]

- 96.El-Agamy DS. Comparative effects of curcumin and resveratrol on aflatoxin B 1-induced liver injury in rats. Archives of Toxicology. 2010;84(5):389–396. doi: 10.1007/s00204-010-0511-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Matés J, Pérez-Gómez C, de Castro IN. Antioxidant enzymes and human diseases. Clinical Biochemistry. 1999;32:595–603. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(99)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Elia AC, Dörr AJM, Mastrangelo C, Prearo M, Abete MC. Glutathione and antioxidant enzymes in the hepatopancreas of crayfish Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) of Lake Trasimeno (Italy) Bulletin Francais de la Peche et de la Protection des Milieux Aquatiques. 2006;(380-381):1351–1361. [Google Scholar]

- 99.El-Demerdash FM, Yousef MI, Radwan FME. Ameliorating effect of curcumin on sodium arsenite-induced oxidative damage and lipid peroxidation in different rat organs. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2009;47(1):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guangwei X, Rongzhu L, Wenrong X, et al. Curcumin pretreatment protects against acute acrylonitrile-induced oxidative damage in rats. Toxicology. 2010;267(1–3):140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Al-Jassabi S, Azirun M, Saad A. Biochemical studies on the role of curcumin in the potection of liver and kidney damage by anti-malaria drug, chloroquine. American-Eurasian Journal of Toxicological Sciences. 2011;3:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mathews V, Binu P, Sauganth-Paul M, Abhilash M, Manju A, Nair R. Hepatoprotective efficacy of curcumin against arsenic trioxide toxicity. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2012;2:S706–S711. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wei Y, Rector RS, Thyfault JP, Ibdah JA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and mitochondrial dysfunction. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14(2):193–199. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Königsberg M, López-Díazguerrero NE, Bucio L, Gutiérrez-Ruiz MC. Uncoupling effect of mercuric chloride on mitochondria isolated from an hepatic cell line. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2001;21(4):323–329. doi: 10.1002/jat.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Vatassery GT, DeMaster EG, Lai JCK, Smith WE, Quach HT. Iron uncouples oxidative phosphorylation in brain mitochondria isolated from vitamin E-deficient rats. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2004;1688(3):265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Andreu GLP, Inada NM, Vercesi AE, Curti C. Uncoupling and oxidative stress in liver mitochondria isolated from rats with acute iron overload. Archives of Toxicology. 2009;83(1):47–53. doi: 10.1007/s00204-008-0322-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Roy DN, Mandal S, Sen G, Biswas T. Superoxide anion mediated mitochondrial dysfunction leads to hepatocyte apoptosis preferentially in the periportal region during copper toxicity in rats. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2009;182(2-3):136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Navarro A, Boveris A. Rat brain and liver mitochondria develop oxidative stress and lose enzymatic activities on aging. American Journal of Physiology. 2004;287(5):R1244–R1249. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00226.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jurczuk M, Moniuszko-Jakoniuk J, Rogalska J. Evaluation of oxidative stress in hepatic mitochondria of rats exposed to cadmium and ethanol. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies. 2006;15(6):853–860. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jasso-Chávez R, Pacheco-Rosales A, Lira-Silva E, Gallardo-Pérez JC, García N, Moreno-Sánchez R. Toxic effects of Cr(VI) and Cr(III) on energy metabolism of heterotrophic Euglena gracilis. Aquatic Toxicology. 2010;100(4):329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rembacz K, Sawicka E, Długosz A. Role of estradiol in chromium-induced oxidative stress. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica. 2012;69:1372–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Priyadarsini KI, Maity DK, Naik GH, et al. Role of phenolic O–H and methylene hydrogen on the free radical reactions and antioxidant activity of curcumin. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2003;35(5):475–484. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhu Y-G, Chen X-C, Chen Z-Z, et al. Curcumin protects mitochondria from oxidative damage and attenuates apoptosis in cortical neurons. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2004;25(12):1606–1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.González-Salazar A, Molina-Jijón E, Correa F, et al. Curcumin protects from cardiac reperfusion damage by attenuation of oxidant stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cardiovascular Toxicology. 2011;11(4):357–364. doi: 10.1007/s12012-011-9128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.He H, Wang G, Gao Y, Ling W, Yu Z, Jin T. Curcumin attenuates Nrf2 signaling defect, oxidative stress in muscle and glucose intolerance in high fat diet-fed mice. World Journal of Diabetes. 2012;3:94–104. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v3.i5.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Waseem M, Kaushik P, Parvez S. Mitochondria-mediated mitigatory role of curcumin in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Cell Biochemistry and Function. 2013 doi: 10.1002/cbf.2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Calabrese V, Lodi R, Tonon C, et al. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular stress response in Friedreich’s ataxia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2005;233(1-2):145–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443(7113):787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Oliveira CPMS, Coelho AMM, Barbeiro HV, et al. Liver mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stess in the pathogenesis of experimental nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2006;39(2):189–194. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2006000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Raza H, John A, Brown EM, Benedict S, Kambal A. Alterations in mitochondrial respiratory functions, redox metabolism and apoptosis by oxidant 4-hydroxynonenal and antioxidants curcumin and melatonin in PC12 cells. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2008;226(2):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sivalingam N, Basivireddy J, Balasubramanian KA, Jacob M. Curcumin attenuates indomethacin-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Archives of Toxicology. 2008;82(7):471–481. doi: 10.1007/s00204-007-0263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sas K, Robotka H, Toldi J, Vécsei L. Mitochondria, metabolic disturbances, oxidative stress and the kynurenine system, with focus on neurodegenerative disorders. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2007;257(1-2):221–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Efremov RG, Baradaran R, Sazanov LA. The architecture of respiratory complex I. Nature. 2010;465(7297):441–445. doi: 10.1038/nature09066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gonzalez-Halphen D, Ghelli A, Iommarini L, Carelli V, Esposti MD. Mitochondrial complex I and cell death: a semi-automatic shotgun model. Cell Death and Disease. 2011;2(10, article e222) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mythri RB, Harish G, Dubey SK, Misra K, Srinivas Bharath MM. Glutamoyl diester of the dietary polyphenol curcumin offers improved protection against peroxynitrite-mediated nitrosative stress and damage of brain mitochondria in vitro: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2011;347(1-2):135–143. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0621-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Izem-Meziane M, Djerdjouri B, Rimbaud S, et al. Catecholamine-induced cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction and mPTP opening: protective effect of curcumin. American Journal of Physiology. 2012;302(3):H665–H674. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00467.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Feldmann G, Haouzi D, Moreau A, et al. Opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore causes matrix expansion and outer membrane rupture in Fas-mediated hepatic apoptosis in mice. Hepatology. 2000;31(3):674–683. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Javadov S, Karmazyn M. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening as an endpoint to initiate cell death and as a putative target for cardioprotection. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2007;20(1–4):1–22. doi: 10.1159/000103747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Halestrap AP, McStay GP, Clarke SJ. The permeability transition pore complex: another view. Biochimie. 2002;84(2-3):153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Xiao J-W, Zhong C-G, Li B. Study of L-02 hepatocyte apoptosis induced by hexavalent chromium associated with mitochondria function damage. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2006;35(4):416–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pritchard DE, Singh J, Carlisle DL, Patierno SR. Cyclosporin A inhibits chromium(VI)-induced apoptosis and mitochondrial cytochrome c release and restores clonogenic survival in CHO cells. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(11):2027–2033. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.11.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ghoneim AI. Effects of curcumin on ethanol-induced hepatocyte necrosis and apoptosis: implication of lipid peroxidation and cytochrome c. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 2009;379(1):47–60. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Eckert G, Schiborr C, Hagl S, et al. Curcumin prevents mitochondrial dysfunction in the brain of the senescence-accelerated mouse-prone 8. Neurochemistry International. 2013;62:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ligeret H, Barthelemy S, Zini R, Tillement J-P, Labidalle S, Morin D. Effects of curcumin and curcumin derivatives on mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2004;36(7):919–929. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cheng C-Y, Lin Y-H, Su C-C. Curcumin inhibits the proliferation of human hepatocellular carcinoma J5 cells by inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2010;26(5):673–678. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wang W, Chiang I, Ding K, et al. Curcumin-induced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma J5 cells: critical role of Ca+2-dependent pathway. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:7 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/512907.512907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Cao J, Liu Y, Jia L, et al. Curcumin induces apoptosis through mitochondrial hyperpolarization and mtDNA damage in human hepatoma G2 cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2007;43(6):968–975. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wang M, Ruan Y, Chen Q, Li S, Wang Q, Cai J. Curcumin induced HepG2 cell apoptosis-associated mitochondrial membrane potential and intracellular free Ca2+ concentration. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;650(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Darvesha AS, Aggarwal BB, Bishayee A. Curcumin and liver cancer: a review. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2012;13(1):218–228. doi: 10.2174/138920112798868791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]