Abstract

Background:

Nursing education is both formal and informal. Formal education represents only a small part of all the learning involved; and many students learn more effectively through informal processes. There is little information about nursing student informal education and how it affects their character and practice.

Materials and Methods:

This qualitative study explores undergraduate nursing student perceptions of informal learning during nursing studies. Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews with a sample of undergraduate nursing students (n = 14). Strauss and Corbin’s constant comparison analysis approach was used for data analysis.

Results:

The categories that emerged included personal maturity and emotional development, social development, closeness to God, alterations in value systems, and ethical and professional commitment.

Conclusion:

Findings reveal that nursing education could take advantage of informal learning opportunities to develop students’ nontechnical skills and produce more competent students. Implications for nursing education are discussed.

Keywords: Informal learning, personal growth, qualitative study, undergraduate nursing education

INTRODUCTION

In modern nursing, nurses are expected to deliver holistic care, taking into account patients’ biological, psychosocial, and spiritual needs.[1,2] However, formal nursing programs in Iran follow a biomedical approach that focuses mainly on medical problems.[3–5] These formal education programs focus on the transfer of knowledge and the mastery of techniques related to patient physical care; however, students also learn informally through hidden curricula of nursing education.

Nursing students learn through both the formal and informal aspects of nursing education. Direct observation of situations, such as birth, death, loss, and suffering results in emotional learning.[6,7] Additionally, students gain experience through interactions with each other, teachers, and senior professionals,[8] known as peer learning,[9] which studies have found can have life-long effects on students.[10] The impact of these learning experiences have seldom been recognized and explored. The limited scope of formal nursing education in Iran may result in informal learning experience for nursing students that differs from those of other countries. If nursing education recognizes this informal learning and its achievements may be able to take advantages of these opportunities to improve students’ competency. Informal or indirect learning can occur as a function of observing, retaining, and replicating behaviors during educational experiences. The aim of this qualitative study was to explore the perceived informal learning achievements in undergraduate nursing programs from the Iranian student perspective.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study question and design

This study was designed to answer the question: what are undergraduate nursing student perceptions of the informal learning that occurs during nursing studies? This study was conducted over a 2-year period (2009-2010) using a qualitative content analysis. The aim of the study was to develop a deep understanding of participants’ perceptions.

Participants

The participants were 14 nursing students in their fourth year of study at “X” university who were recruited through a purposeful sampling method. They were at their final stage of clinical apprenticeship so had passed major part of their education and could share their achievements of learning experiences, including informal ones. Sampling was done according to the maximum variant approach in terms of gender, age, marital status, geographical location (local or not local), student work experience, and level of academic achievement (e.g., good, average, or superior). All of the participants were Muslim.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected through face-to-face individual interviews. The interviews were semi-structured and conducted using an interview guide. Each interview began with the open question: “Apart from the theoretical and practical knowledge you gained during four years of nursing study, what other changes do you think you have experienced during your study?” Answers were explored more deeply with relevant probing statements or questions, such as: “Please tell me more about that,” “How did that make you feel?” or “Please describe an actual experience you have had that will help me understand what it meant to you.” The interviews lasted an average of 70 min, usually in a single session. Data gathering was stopped when duplication of previously obtained data occurred.

Each interview was transcribed verbatim, and then converted to Rich Text Format for use in MAXqda software, which facilitated data management. Data were analyzed through a constant comparison analysis method using Strauss and Corbin coding techniques[11,12] to develop the categories. Data were analyzed initially by the main author, then the emerging codes were revised independently by 2 other members of the research team. Throughout coding and category development, the analysis process and the accuracy of codes and categories were discussed and checked in regular sessions; discrepancies were resolved through continuing discussion and analysis.

Rigor

Lincoln and Guba (1985) criteria were used to address trustworthiness (p.296). Dependability was gained by precise documentation of data, methods, and decisions about the research. Credibility was established through participant confirmation of our understanding, prolonged engagements with participants, a peer check, and an external check. Throughout the study, data were managed by MAXqda and all analysis precisely documented to maintain an audit trail.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the university ethics review board. Student participation was voluntary. Written information about the purpose of the study and confidentiality management was delivered to all participants and written consent was obtained for the study, including permission for recording the entire interview for transcribing.

Findings

The 14 participants consisted of 3 male and 11 female nursing students, age 21-23 years, in the last semester of their studies.

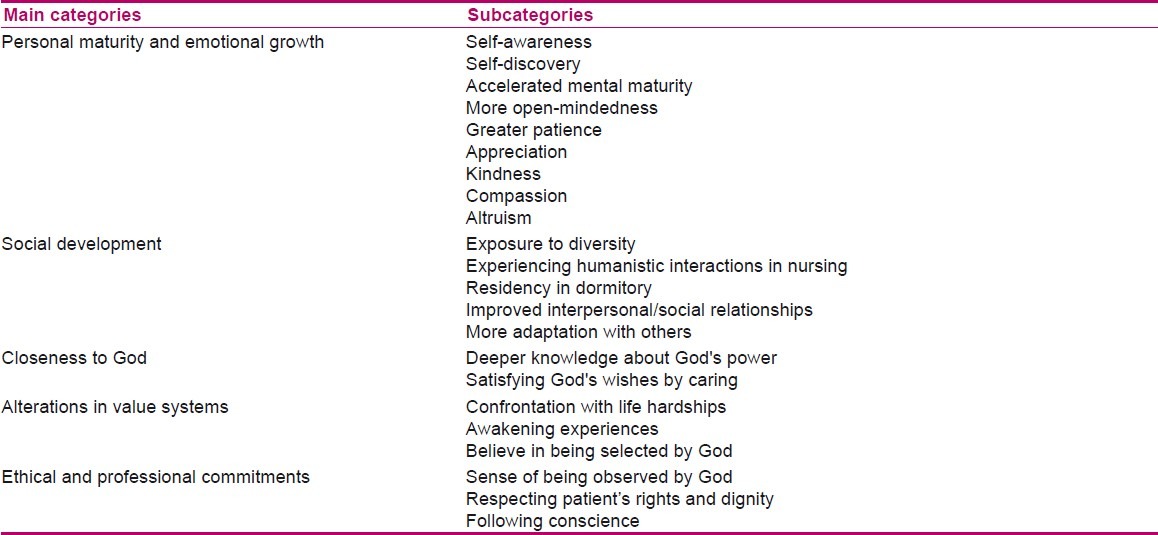

Based on students’ experiences, 5 categories were extracted: personal maturity and emotional growth, social development, closeness to God, alterations in value systems, and ethical and professional commitments [Table 1]. Although some participants described the process leading to their internal changes as challenging and difficult, almost all of them stated that it facilitated their growth as a whole person.

Table 1.

Students’ achievements of informal learning during nursing study

Personal maturity and emotional growth

This category consisted of 2 subcategories: personal maturity (consisting of self-awareness and self-discovery, accelerated mental maturity, and more open-mindedness) and emotional growth (consisting of greater patience, appreciation, kindness, and compassion, and altruism).

The participants viewed their 4 years in nursing school as an opportunity for gaining a deeper self-awareness and self-knowledge. They believed that the duties of nursing practice, such as frequent personal interactions and development of relationships, have great influence on deep reflection about humanity as well as their personal beliefs. In contrast, the importance of rigorous assessment throughout nursing studies resulted in regular self-assessment in their daily lives. These helped them obtain more realistic knowledge about their personal strengths, weaknesses, and talents. Some participants described this awareness as self-discovery by saying:

“I learned about myself based on what they taught us about humans in the program. I understood myself, in the university setting, through the eyes of my friends, who criticized me. I read books and analyzed and evaluated many of my behaviors. Now I understand myself better.”

Another significant change reported by students was an increasing maturity of mind that resulted in more rational behavior. The frequent exposure to life-and-death situations in nursing helped promote maturity. One student said:

“My personality developed at this school. At first, I behaved very childishly. There were a series of realities of which I was wholly ignorant; I acquired them here in the school.”

They also attributed this increase in maturity to multiple factors, including interactions with instructors, senior students, and people with various personalities, as well as engagement in difficult situations. One participant said:

“This maturity has been partly influenced by interactions with professional instructors and encounters with classmates as well as senior students… I improved little by little through experiencing critical situations, seeing the darker side of life, the troubles and pains of other people, all of which I was unaware of in my previous relaxed lifestyle.”

The other significant experience reported by participants was increasing open-mindedness. With respect to the principles of fundamental nursing classes, they learned to focus on a patient as a human being, regardless of nationality, ethnicity, religious beliefs, or financial or sociocultural status. These principles made them receptive to diversity and differences. As a result, students reported that they were able to accept people by adopting a nonjudgmental manner. One student, who was caring for people with various religious beliefs, described her primary concern about encountering clients with different beliefs as a challenging experience and explained how she successfully overcame those conflicts by overlooking religious prejudices. She said:

“At first I thought I had treated them differently; well, one patient was Muslim, the other held another belief. However, after a while, I realized that they are ultimately human, and my job was not to judge the belief system of people. Then the differences were no longer serious or problematic and I found myself adapting easily by getting closer to them. I am very grateful to be able to communicate well with various religious minorities despite so many differences.”

Almost all of the participants indicated that increasing patience was their most significant change. Some of them said that they learned patience from patients who were suffering from chronic illnesses. When they saw how these patients worked to manage the disease and its disabling consequences, they realized the triviality of their own problems. One of them talked about learning from patients by saying:

“I saw many patients during this period. I had patients who underwent dialysis every day, yet were quite happy, spoke with joy, laughed, and induced others to be in a good mood. In comparison with them, how could I concern myself with minor issues while I was in good health physically and emotionally? I felt embarrassed when I saw them struggle steadfastly with such pain, illness, and deprivation.”

Other participants believed that the patience resulting from the nature of discipline made them stronger to handle difficulties. Continuous engagements with people who need support helped them to be calm and strong. They behaved in a way expected of nurses. One participant stated:

“Nowadays the problems do not exhaust my spirit. Since in nursing practice you see the pains and troubles of other people, a series of problems are no longer considered problems, or perhaps your experiences and abilities have improved. You should be more patient, in order to help those people who need you and have their hope invested in you.”

Another achievement mentioned by the participants was being appreciative. They said seeing patients suffer made them realize the importance of the gifts they took for granted, especially the gift of health:

“I was very unthankful and ignorant of what I had. Now I see patients with their problems and realize the gifts I have in my life, which I didn’t appreciate before. Now I always give thanks to God for all of them.”

They also explained that nursing made them similar to mothers-kind and ready to help and show compassion. Now they feel a stronger sense of love and concern for humankind as well as the ability to love and care for others. One of them indicated:

“Studying in the nursing field gives you the sense of being a mother. Mothering makes you clear and kind... I feel that I must show sympathy to all. They teach us that we must be able to establish good communication, and understand others and support them. Well, you internalize it when you constantly hear it for several years. Automatically you become always ready for listening and assisting others.”

Some participants indicated that nursing strengthened their altruism. One participant stated:

“Generally, my morale and personality is such that I really like people. This sense was much enhanced and established in me through nursing. It seems that these traits were developed for inner satisfaction and for the affection you can induce in others.”

Social development

The second category derived from the interviews was related to becoming more social and expert in interpersonal relationships. Some of the participants, especially those who had limited communication skills before entering the program, acknowledged nursing studies as a turning point that improved their social relationships. They asserted that gaining communication skills with patients in clinical settings as fundamental to improving their interpersonal proficiency by saying:

“Nursing improved my communication with others. I, who had a habit of building fences around me, was forced out of that closed space. During this period, my communication skills got much stronger, since they are required and necessary skills in nursing.”

Encouraging and developing communication with patients required students to exploit strategies, such as developing cultural and ideological common ground, respecting others’ interests and wishes, and adapting themselves to others. Gradually they noticed they were applying these advanced communication skills in their personal life.

“The limitations I had set for myself faded away in the nursing program. Now, I can look at the subject from his/her point of view. I take the initiative and try to begin from a point that is welcomed by the other party. This all happened because of the nursing program. I moved away from a partial and limited understanding of others and I feel that I am growing in regards to social relations in general.”

Another factor that contributed to students’ social development was existing in a social environment larger than that of high school, which involved interaction with a heterogeneous population from various towns, ethnic groups, and cultures, which was regarded as expanding “the friends circle” by participants:

“I tried to experience all group types. Currently my friends vary in all aspects and types. I don’t limit myself to making friends with people of my own type; I always search for new thoughts and new ideas with their own experiences. Every friend opened a new window to a different world.”

Nonlocal participants, who resided in the student dormitory during their studies, explained the significant influence of living in the dormitory on their social growth and development as:

“When you become a college student and live in the dormitory with other students coming from different places and cultures with various upbringings, you are obliged to encounter them, and automatically learn how to adapt yourself and in fact be flexible. You must submit yourself to the group and adapt yourself in return.”

Closeness to God

Since all participants were Muslim, a belief in God was one fundamental characteristic. However, most of them stated that they experienced a different type of connection with God during their nursing studies. They described it as a new form of understanding of and feeling toward God. Some of them attributed this new belief to gaining a deeper knowledge about the intricacies of the human body and about human beings in general during the nursing program:

“I sense that my understanding of God is enhanced. I understood the complexities of this perfect system (the human body), how accurately it has been designed, and how many problems are caused by a small deviation. I came across various diseases that were scarce and deadly. We were told that the patients don’t respond to any treatment, but they did and I saw with my own eyes the effect of the prayers that the person accompanying the patient offered from the depths of the heart, and how it worked. I touched God’s power and presence.”

Others stated they felt closer to God through nursing practice because they were satisfying God’s wishes by caring for the most vulnerable. This caused them to be more hopeful in their relationship with God. This optimism significantly improved the quality of their prayers and replaced traditional ceremonies with enthusiastic worship and inner dialog with God. This type of close connection with God led to a pleasant feeling of dependency, which made them calmer when confronting difficulties:

“Now I feel that God is looking at me, for my interest in caring for his people. Prayers provide me with a good feeling. I tell myself since I serve God’s people sincerely; certainly He would also pay attention to me... I have noticed that whenever I have troubles, they are resolved at once. I sense some resolution and interpret it as God’s promise that, if you help someone, God will help you in return.”

Alteration in value systems and beliefs

Participants believed that confrontation with the light as well as the dark side of life in nursing expanded their world view through a change in focus from living a superficial life to a life more concerned with serious and substantive matters beyond their calendar age. One participant explained:

“In nursing, you see the beginning of life… and the termination of it. … You are faced with certain facts that make other issues trivial and insignificant in life while they are still important for your peers. It makes you feel older than what you really are.”

These challenging confrontations acted as awakening experiences, allowing students to obtain a new perspective about life and death that stimulated changes in their value systems. As a result, their values differed from what they were originally. They described these alterations as achieving a deeper and more realistic point of view of life:

“Now my objectives for the future have changed in principle. Whenever I see patients who have only a few days to live, I no longer waste my time. …Before, I had a child-like view of life as a bowl of cherries with no worries, but now I know that life has its own hardships, which are considered a part of life. So, I try to adapt myself. Now I place little value on material things that are simply doomed... I seek deep relaxation and self-esteem as my purpose in life. I would like to have the competency that is apparent in spiritual people.”

Moreover, most of them asserted that they feel they were chosen by God for this profession and they appreciated it as an opportunity for growth and transcendence. One of the participants expressed her emotions about being selected:

“I sensed that I was invited by God to take a right path that changed my destiny forever. I began taking steps on a road that I was supposed to begin with and I interpreted this as special attention to me on God’s part... I believe that we were summoned by God. Nurses were invited for their kind heart, for their sympathy, and for their ability to provide relaxation to patients. If you knew this from the beginning and you appreciated being invited, any experience along the way would become important and valuable to you.”

Ethical and professional commitment

Most participants admitted that they feel a strong commitment to their work and try to be conscientious in the care of their patients. They believed that this inner commitment had a stronger influence than any rules or external controls. Some of them attributed this inner commitment to their increased closeness to God and consequent sense of being observed constantly by God. They were delighted by this connection and attention so they tried to sustain this perceived attention by working ethically and conscientiously. One of them stated:

“Many nurses deliver conscientious care despite the problems they face financially. At least I am that way. Even though I can work unsterile and the patient may not know it, I notice what I do and God does, too. However, your ethical commitment forces you to work better. To me, respecting the patient’s rights is more important than anything else. I always tell myself to imagine that the patient is one of your dear siblings. I always try to hold that thought and work according to such feelings to do my best.”

In addition, participants attributed this commitment to other reasons, such as respecting patient’s rights and dignity to enjoy humanistic and proper care as a human being, responding their inner desire to do their best as a nurse, and trying to improve nursing image in society. One participant related her sense of ethical and professional commitment to satisfaction of her inner philanthropic desire:

“To me, it does not matter whether someone see or appreciate my efforts or ethically working. Doing my best firstly as a human, secondly as a nurse satisfies me, so it is enough to follow my inner voice and desire to work as well as I can to help a needy patient to make him/her condition better.”

DISCUSSION

Since students who felt more personal growth were more eager to participate in the study, it is possible that other students’ experiences have been ignored unintentionally by the researchers.

According to the results of this study, the undergraduate nursing students achieved knowledge and insights that were not provided by the formal, biomedical-centered, nursing program. These included the following: personal maturity and emotional development, social development, greater closeness to God, an alteration in value systems, and ethical and professional commitment. These are nontechnical professional competencies that are important to the goals of the nursing curriculum. Although these are not included in a specific lesson, they are beyond theoretical knowledge and the technical skills and could be considered as the soul of nursing education. The results indicate that nursing students develop important qualities through a “hidden curriculum” that help fulfill the mission of nursing education in creating ethical, spiritual, legal, and professional values.

In this study, one of the most important categories was personal growth, which included self-awareness, self-knowledge, and self-discovery due to frequent interactions with patients and other people and reflection on the experiences of these relationships. The meaning of this category was compatible with that of a previous study,[13] indicating a self-awareness theme related to experiences of being and presence. Participants in the previous study also experienced nurse-patient interactions that resulted in self-awareness. The participants who increased self-awareness did so through reflection, and found meaning in being a nurse. Even registered nurses found the means for personal growth. According to Lee,[14] Chiu[15] the outcome of university courses are not limited to professional development; they also promoted the personal growth of nurses.

Being a nurse requires compassion, respect, and humanity. In the present study, participants described nursing as an opportunity to gain empathy and other humanistic feelings. They appreciated the characteristics, such as patience, thankfulness, kindness, compassion, and concern about humankind, that could help them achieve emotional growth.

Emotional growth means the increasing capacity to recognize one’s own emotions and allow them to mature.[16] Wilson,[17] stated that nursing students develop emotional competence by critical reflection through classroom sessions and clinical experiences. The participants in the present study also indicated that reflection occurred outside formal sessions in the classroom. Because nursing is a profession involving difficult situations, nursing students need preparation to mature enough to successfully handle their professional role, especially during a crisis. Studies reveal that nurses younger than 30 years experience greater burnout than their older counterparts.[18] Such findings support the idea that emotional issues should be addressed in nursing curricula to nurture a healthier and more competent nursing workforce.[19]

The participants in the present study also emphasized improvement in interpersonal and communication skills as a result of their nursing studies. They believed that nursing taught them to put themselves in the patient’s place and see through their eyes, which increased the awareness of patients’ feelings, perceptions, and needs. These critical abilities are referred to as social growth qualities, gained through interactions with professors, classmates, roommates, and patients while out of the classroom. Rahimaghaee et al[20] reported similar improvements in communication as an indicator of professional growth.

Although our participants were Muslims, who must maintain a respectful distance from members of the opposite sex that can interfere with some nursing tasks, findings indicated that even the strongly religious female participants did not have problems caring for male patients.

Another aspect of nursing training that affected students in this study was their relationship with God. From an Islamic perspective, care is seen as a service to God.[21] Additionally, nursing is considered a divine profession in Iran.[5] In this ideologic context, almost all of the study participants appreciated nursing as a call from God toward transcendence. Ravari et al.[22] also reported that the perception of nursing as an opportunity to worship God is a common belief among Iranian nurses, which provided their career a transcendental meaning.

The study participants reported changes in their value systems, such as finding a deeper meaning beyond the superficial activities of everyday life and more lasting goals and values. University studies provided an awakening experience, and inspired students to re-evaluate and redefine their personal values. Since universities are expected to help students achieve a broader perspective, nursing education should help promote student receptivity of human values compatible with their professional mission. Such changes in the students’ value systems have been reported. Lemonidou et al.[23] indicated that empathizing with patients and caring about their feelings initiates an ethical reflection process in nursing students that may eventually lead to the development of a set of personal values.

The last category revealed that, although the participants were just starting their career, they gained a sense of professional and ethical commitment. In a similar study by Rahimaghaee et al,[20] participant views about commitment went beyond work commitment to include an inner commitment related to a belief in God’s supervision of their lives, including their careers. Additionally, Le Duc and Kotzer,[24] found that even novice nurses can hold professional values, indicating that nursing education can initiate a sense of professional commitment in students.

CONCLUSION

According to some nursing theorists, including Watson, nursing schools should acknowledge the “hidden learning” that occurs outside the classroom can foster and facilitate development of students as whole human beings, not just professional nurses. According to Watson,[25] curriculum development should combine and integrate the cognitive with education about beauty, art, ethics, intuition, esthetics, and spirituality of human-to-human interactions within nursing. The nursing discipline needs to incorporate this type of curriculum to improve nursing student’s personal development. During their education, nursing students have very close interactions with patients compared with those from other disciplines. They observe different types of patient experiences and are affected by these experiences. This aspect of nursing was reported by Paterson and Zedrad (2007) in their humanistic nursing theory.[26]

The findings of this study revealed that nursing education, especially clinical training with its patient-student interactions, provides an excellent opportunity for student personal growth that is less likely in other majors. Through their studies, nursing students do not gain expertise in theoretical and technical matters alone, but also fulfill their potential as a whole person. Nursing education can prepare students to deliver holistic care only if they consider all aspects of the students as humans. The ability to provide holistic care of patients requires treating each nursing student as a whole person through both formal and informal education.

This idea agrees with theories of student development that consider college education as involving the whole person and as a process involving interaction between intellectual development and interpersonal competence. Therefore, recognizing and encouraging covert aspects of nursing education as well as overt ones provide more opportunities for student development, not only in cognitive and technical domains but also in affective ones. This can help bring nursing education closer to the ideal of comprehensiveness that enables nurses to care holistically for patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This article was part of PhD thesis supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The authors are grateful to all participants who helped in conducting the present study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: None

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rankin EA, Delushmut MB. Finding spirituality and nursing presence: The student’s challenge. J Holist Nurs. 2006;24:282–8. doi: 10.1177/0898010106294423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson S. Factors impacting on nurses’ transference of theoretical knowledge of holistic care in to clinical practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 2002;2:224–50. doi: 10.1016/s1471-5953(02)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khomeiran RT, Deans C. Nursing education in Iran: Past, present, and Future. Nurse Educ Today. 2007;27:708–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tavakol M, Rahemei-Madeseh M, Torabi S, Goode J. Opposite gender doctor- patient interactions in Iran. Teach Learn Med. 2006;18:320–5. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1804_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikbakht Nasrabadi AN, Emami A. Perceptions of nursing practice in Iran. Nurs Outlook. 2006;54:320–7. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christiansen B, Jensen K. Emotional learning within the framework of nursing education. Nurse Educ Pract. 2008;8:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher JE. Fear and learning in mental health settings. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2002;11:128–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0979.2002.t01-1-00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sartorio NA, Zoboli EL. Images of a ’good nurse’ presented by teaching staff. Nurs Ethics. 2010;17:687–94. doi: 10.1177/0969733010378930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boad D, Cohen R, Sampson J. Learning from and with each other. London: Kogan Page; 2001. Peer learning in higher education. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvin RE. Research on cooperative learning: Consensus and controversy. Educ Leadersh. 1990;47:52–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babamohamadi H, Negarandeh R, Dehghan-Nayeri N. Barriers to and facilitators of coping with spinal cord injury for Iranian patients: A qualitative study. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13:207–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. 3th Ed. London: Sage publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Idczak SE. Nursing students’ experiences of being and presence: A Hermeneutic approach [Ph.D thesis] The University of Toledo; May, [Last accessed on 2005]. Available from: http://www.rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=toledo1115122643 . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chui LH. Malaysian Registered Nurses’ Professional Learning. Int J Nurs Educ Sch. 2006;3:art 16. doi: 10.2202/1548-923X.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy G. Professional progress through personal growth. Am J Nurs. 1954;54:1464–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson CS. Master thesis. New Zealand: Massy university; A qualitative exploration of emotional competence and its relevance to nursing relationships. Available from: http://mro.Massey.ac.nz/handle/10179/263 . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erickson R, Grove W. Why Emotions Matter: age, agitation, and burnout among registered nurses. Online J Issues Nurs. 2007;13 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loukidou E, Ioannidi V, Kalokerinou A. Special educational strategies for nursing staff. Sport MInt J. 2010;6:29–42. D.O.I: http:dx.doi.org/10.4127/ch.2010.0043 . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahimaghaee F, Nayeri ND, Mohammadi E. Iranian Nurses’ perceptions of their professional growth and development. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;16:10. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01PPT01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rassool GH. The crescent and Islam: Healing, nursing and the spiritual dimension. Some considerations towards an understanding of the Islamic perspectives on caring. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1476–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravari A, Vanaki Z, Houmann H, Kazemnejad A. Spiritual job satisfaction in an Iranian nursing context. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16:19–30. doi: 10.1177/0969733008097987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemonidou C, Papathanassoglou E, Giannakopoulou M, Patiraki E, Papadatou D. Moral Professional Personhood: Ethical reflections during initial clinical encounters in nursing education. Nurs Ethics. 2004;11:122–37. doi: 10.1191/0969733004ne678oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeDuc K, Kotzer AM. Bridging the gap: A comparison of the professional nursing values of students, new graduates, and seasoned professionals. [Last accessed on 2011 Dec 04];Nurs Educ Perspect. 2009 30:279–84. Available from: http://www.thechildrenshospital.org/pdf/Pub_List_2005-09 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson J. Nursing Human science and Human Care. London: Jones and Bartlett; 1989. p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meleis AI. Theoretical nursing development and progress. 4 ed. New York: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkines; 2007. p. 359. [Google Scholar]