Abstract

Nerve growth factor (NGF) and most neurotrophic factors support the proliferation and survival of particular types of neurons. Besidesthe pivotal role of NGF in the development of neuronal cells, it also has important functions on non-neuronal cells. The amnion surrounds the embryo, providing an aqueous environment for the embryo. A wide range of proteins has been identified in human amniotic fluid (AF). In this study, total protein concentration (TPC) and NGF level in AF samples from chick embryos were measured using a Bio-Rad protein assay, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot. TPC increased from days E10 to day E18. There was a rapid increase in AF TPC on day E15 when compared to day E16. No significant changes in NGF levels have been seen from day E10 to day E14. There was a rapid increase in NGF content on days E15 and E16, and thereafter the levels decreased from day E16 to day E18. Since, NGF is important in brain development and changes in AF NGF levels have been seen in some CNS malformations, changes in the TPC and NGF levels in AF during chick embryonic development may be correlated with cerebral cortical development. It is also concluded that NGF is a constant component of the AF during chick embryogenesis.

Keywords: Amniotic fluid, Chick, Concentration, ELISA, Nerve growth factor, Western blotting

1. Introduction

Nerve growth factor (NGF), originally identified as a neurite-promoting factor in peripheral sensory and sympathetic neurons, has been shown to function in the central nervous system (Spranger et al., 1990; Chiaretti et al., 2008). NGF, discovered almost half a century ago, is the founding and best-characterized member of neurotrophin family (Levi-Montalcini, 1987; Chao, 1992). The biological function of NGF is the maintenance and survival of the nervous system. Besides the pivotal role of NGF in the development of neuronal cells, it also has important functions on non-neuronal cells. For example, it is an autocrine survival factor for memory B lymphocytes (Torcia et al., 1996).

The neurotrophins represent a family of structurally and functionally related, homodimeric proteins, including NGF, brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), NT-4, NT-4/5 and NT-6 (Götz et al., 1994). NGF exerts its differentiating and proliferation effects on the CNS during embryonic development. Some non-neuronal cell types can release NGF in a paracrine/autocrine fashion (Jiang et al., 1997).

Biological actions of NGF are mediated by two distinct receptors, the high-affinity trkANGFR receptor and the low-affinity p75NTR receptor (Yano and Chao, 2000). It has been shown that NGF exerts indirect pro-angio-genetic effects mediated by specific angiogenic factors in the developing CNS (Calza et al., 2001) and that it induces increased expression of inflammatory markers in skin vessels (Raychaudhuri et al., 2001).

The amnion, which is the inner membrane, surrounds the embryo, forming the amniotic cavity, providing an aqueous environment for the embryo. The amnion contains a fluid to protect the embryo from infection, mechanical injury, and adhesion. The chick begins imbibing the amniotic fluid (AF) around day 13 of incubation and continues until day 19 of incubation. Hence, the embryo is exposed to and swallows the fluid containing proteins, minerals, water, hormones and any other nutrients needed for growth and development (Karcher et al., 2005).

AF is crucial to fetal health because it forms a protective sac around the infant that prevents mechanical and thermal shock, possesses antimicrobial activity, assists in acid/base balance, and contains nutritional factors. A wide range of proteins has been identified in human AF (Burdett et al., 1982). In human, these proteins can enter the amniotic fluid from the maternal uterine tissues, umbilical cord, amniotic fluid cells, fetal urine, meconium, and other fetal secretions that include transudation through fetal skin (Jauniaux et al., 1998). There is also a dynamic temporal pattern, with AF total protein concentrations rising from 7 to 20 weeks gestation (Benzie et al., 1974).

In this study, the total protein concentration (TPC) in chick amniotic fluid was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay based on the Bradford dye-binding procedure. The presence and level of NGF in chick amniotic fluid was measured by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blot.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Amniotic fluid samples

Fertile white Leghorn eggs were incubated at 38 °C in a humidified atmosphere to obtain chick embryos at different stages of development. The amniotic fluid was carefully aspirated using a pulled tip glass microcapillary pipette (Drummond Scientific Company, 20 μL) from incubated chick embryos from day 10 to day 18 (E10–E18).

Amniotic fluid for each analysis was collected from 28 chick embryos. The amount of 0.5 ml amniotic fluid was collected from each embryo. To minimize protein degradation, amniotic fluid samples were kept at 4 °C during collection. Amniotic fluid samples were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min to remove any contaminating cells. The samples that we used for analysis had no visible sign of contaminating red blood cells that we could detect under the microscope. The supernatant was frozen immediately and stored at −70 °C until future analysis. Twenty eight samples from each time point were used for analysis of total protein and NGF concentration.

2.2. Total protein and NGF analysis

The total protein concentration of proteins in the amniotic fluid was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay based on the Bradford dye procedure. NGF in amniotic fluid was measured using the sensitive two-site ELISA and antiserum against chick NGF. Microtiter plates (Dynatech, Canada) were first coated with 80 ng primary anti-NGF antibody (Abcam) per well in 0.1 M Tris buffer. After overnight incubation, the plates were blocked with EIA buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 0.3 M NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% BSA and 1% gelatin). The samples and standards were placed in triplicate wells and incubated overnight at room temperature. After washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) a biotinylated secondary antibody (8 ng/mL) was added to each well and incubation was carried out overnight at room temperature. β-Galactosidase coupled to avidin was then added for 2 h followed by washing. Finally, 200 μM 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-galactoside (Sigma–Aldrich, Poole, UK) in 50 mM sodium phosphate were added as well as 10 mM MgCl2 buffer and the amount of fluorescence was measured after 50 min incubation at 37 °C using a fluorimeter (Dynatech, Canada).

For Western Blot analysis, aliquots of amniotic fluid from the embryos were mixed with a sample buffer containing 3.2% SDS, 15% glycerol, 2.8 M β-mercaptoeyhanol and 0.0015% bromophenol blue. Samples were applied to a 5–20% gradient SDS–PAGE gel (Bio-Rad) according to Lamely and the proteins obtained were transferred to nitrocellulose sheets, pore size 0.45 μm (Bio-Rad). After incubation for 2 h at room temperature in the blocking solution (PBS containing 5% skimmed milk), the nitrocellulose sheets were exposed overnight, at 4 °C, to anti-NGF monoclonal antibody and identified with a peroxidase-labeled mouse IgM PK 4010 Vectastain Avidin Biotin complex kit (Vectorlab.). The peroxidase activity was revealed with diaminobenzidine (0.5 mg/ml in PBS with 0.02% hydrogen peroxide).

All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the Animals Act, 1986. All values were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). In all experiments, a minimum of 28 measurements were made in order to calculate a mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test and only values with P ⩽ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Total protein concentration

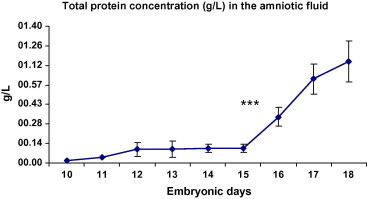

The total protein concentration in AF in embryos aged E10–E18 was determined by Bio-Rad protein assay. The total protein concentration increased from day E10 to day E18. There was a rapid increase in AF TPC on day E16 when compared to day E15 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Total protein concentration in the amniotic fluid samples from days E10 to E18 (g/l). Significant increase in AF total protein concentration has been seen in E16 when compared with E15 (P < 0.001). ∗∗∗P < 0.001 (n = 28 at each time point).

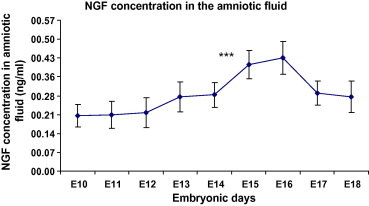

3.2. NGF concentration

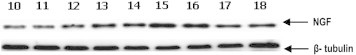

The presence of NGF in the AF samples was shown using Western blot (Figs. 2 and 3). Using ELISA, we have also analyzed NGF concentrations in the AF samples from the chick embryos aged E10–E18. No significant changes in NGF levels have been seen from days E10 to day E14. There was a peak in NGF concentration on days E15 and E16, after that NGF levels decreased from days E16 to day E18 (Fig. 4). The mean NGF concentration in the AF from day 14 was 0.40 ± 0.03 ng/ml, which was significantly higher than the 0.43 ± 0.03 ng/ml of the AF from day 15 (P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of NGF expression in the AF from days E10 to E18. β-Tubulin (50-kDa) expression was determined as a protein loading control (n = 28 at each time point).

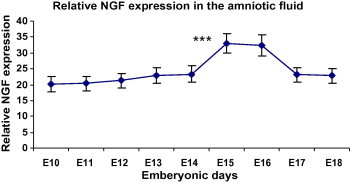

Figure 3.

Signal intensities from the anti-NGF-1 immunoblotting experiments were determined by densitometric analysis. Results shown are mean ± standard error of the mean. Significant increase in AF NGF level has been seen in E15 when compared with E14 (P < 0.001). ∗∗∗P < 0.001 (n = 28 at each time point).

Figure 4.

Nerve growth factor concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid samples from days E10 to E21 (pg/ml). Significant increase in AF NGF level has been seen in E15 when compared with E14 (P < 0.001). ∗∗∗P < 0.001 (n = 28 at each time point).

4. Discussion

We have previously shown that NGF is an important growth factor in cerebral cortical development by stimulating neuronal precursor cell proliferation (Mashayekhi and Salehi, 2007). Using anti-NGF antibody we have demonstrated that NGF has an important role in neuronal cell death in the developing cerebral cortex (Mashayekhi, 2008. It has also been demonstrated that NGF induces eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) in brain tissue (Salehi and Mashayekhi, 2007).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the concentrations of NGF in the chick amniotic fluid. We investigated NGF as it is the first discovered and one of the most important neurotrophins (Shooter, 2001). Neurotrophins are important for the development and maintenance of the nervous system. NGF, the best characterized member of the neurotrophin family, sends its survival signals through activation of TrkA. NGF promotes survival events even at low concentrations of NGF if TrkA is co-expressed on the cell surface (Yano and Chao, 2000).

AF is important to fetal health because it forms a protective sac around the embryo that contains nutritional and growth factors (Stewart et al., 2001). A wide range of proteins has been identified in human AF. In humans, there are dynamic temporal patterns with AF total protein concentrations rising from 7 to 20 weeks of gestation (Tisi et al., 2004). Fetal swallowing represents the principle mechanism of clearance of AF protein, which is thought to have a half-life of 1–2 days in monkeys; however, before keratinization of fetal skin at 24 weeks, diffusion of the lower-molecular weight proteins across unkeratinized fetal skin may occur (Dale et al., 1985). Fetal swallowing of AF begins early in development (Ross and Brace, 2001), where it is shown that proteins can be absorbed from AF by the developing fetuses of rats and monkeys (Lev and Orlic, 1972).

In this study we have shown that total protein concentration in AF increases from days E10 to day E18. We have also shown that there is no significant change in NGF levels in AF from days E10 to day E14. There was a peak in AF NGF levels on days E15 and E16, after that NGF levels decrease from days E16 to E18.

5. Conclusions

Since NGF is important in brain development and changes in AF NGF levels has been seen in some CNS malformations, changes in the total protein concentration and NGF levels during chick embryonic development may be correlated with cerebral cortical development. It is also concluded that NGF is a constant component of the AF during chick embryogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the University of Guilan and University of Mohagegh Ardabili. The authors thank Professor A. Ghanadzadeh, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences, Guilan University for his technical support.

References

- Benzie R.J., Doran T.A., Harkins J.L., Owen V.M., Porter C.J. Composition of the amniotic fluid and maternal serum in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1974;119:798–810. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(74)90093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdett P., Lizana J., Eneroth P., Bremme K. Proteins of human amniotic fluid. II. Mapping by two-dimensional electrophoresis. Clin. Chem. 1982;28:935–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calza L., Giardino L., Giuliani A., Aloe L., Levi-Montalcini R. Nerve growth factor control of neuronal expression of angiogenetic and vasoactive factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;27:4160–4165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051626998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao M.V. Neurotrophin receptors: a window into neuronal differentiation. Neuron. 1992;9:583–593. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaretti A., Antonelli A., Mastrangelo A., Pezzotti P., Tortorolo L., Tosi F., Genovese O. Interleukin-6 and nerve growth factor upregulation correlates with improved outcome in children with severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2008;25:225–234. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale B.A., Holbrook K.A., Kimball J.R., Hoff M., Sun T.T. Expression of epidermal keratins and filaggrin during human fetal skin development. J. Cell Biol. 1985;101:1257–1269. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz R., Köster R., Winkler C., Raulf F., Lottspeich F., Schartl M., Thoenen H. Neurotrophin-6 is a new member of the nerve growth factor family. Nature. 1994;17:266–269. doi: 10.1038/372266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauniaux E., Gulbis B., Hyett J., Nicolaides K.H. Biochemical analyses of mesenchymal fluid in early pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998;178:765–769. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Ulme D.S., Dickens G., Chabuk A., Lavarreda M., Lazarovici P., Guroff G. Both p140(trk) and p75(NGFR) nerve growth factor receptors mediate nerve growth factor-stimulated calcium uptake. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;14:6835–6837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.6835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karcher D.M., McMurtry J.P., Applegate T.J. Developmental changes in amniotic and allantoic fluid insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and -II concentrations of avian embryos. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2005;142:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev R., Orlic D. Protein absorption by the intestine of the fetal rat in utero. Science. 1972;177:522–524. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4048.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Montalcini R. The nerve growth factor 35 years later. Science. 1987;4:1154–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.3306916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashayekhi F. Neural cell death is induced by neutralizing antibody to nerve growth factor: an in vivo study. Brain Dev. 2008;30:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashayekhi F., Salehi Z. Infusion of anti-nerve growth factor into the cisternum magnum of chick embryo leads to decrease cell production in the cerebral cortical germinal epithelium. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007;14:181–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raychaudhuri S.K., Raychaudhuri S.P., Weltman H., Farber E.M. Effect of nerve growth factor on endothelial cell biology: proliferation and adherence molecule expression on human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2001;293:291–295. doi: 10.1007/s004030100224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M.G., Brace R.A. National institute of child health and development conference summary: amniotic fluid biology – basic and clinical aspects. J. Matern. Fetal Med. 2001;10:2–19. doi: 10.1080/714904292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi Z., Mashayekhi F. Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) expression in the brain tissue is induced by infusion of nerve growth factor into the mouse cisterna magnum: an in vivo study. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2007;304:249–253. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shooter E.M. Early days of the nerve growth factor proteins. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:601–629. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spranger M., Lindholm D., Bandtlow C., Heumann R., Gnahn H., Näher-Noé M., Thoenen H. Regulation of nerve growth factor (NGF) synthesis in the rat central nervous system: comparison between the effects of interleukin-1 and various growth factors in astrocyte cultures and in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1990;2:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1990.tb00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C.J., Iles R.K., Perrett D. The analysis of human amniotic fluid using capillary electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:1136–1142. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683()22:6<1136::AID-ELPS1136>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisi D.K., Emard J.J., Koski K.G. Total protein concentration in human amniotic fluid is negatively associated with infant birth weight. J. Nutr. 2004;134:1754–1758. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.7.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torcia M., Bracci-Laudiero L., Lucibello M., Nencioni L., Labardi D., Rubartelli A., Cozzolino F., Aloe L., Garaci E. Nerve growth factor is an autocrine survival factor for memory B lymphocytes. Cell. 1996;3:345–356. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano H., Chao M.V. Neurotrophin receptor structure and interactions. Pharm. Acta Helv. 2000;74:253–260. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6865(99)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]