Abstract

Animal behaviour studies have begun to incorporate the influence of the social environment, providing new opportunities for studying signal strategies and evolution. We examined how the presence and sex of an audience influenced aggression and victory display behaviour in field-captured and laboratory-reared field crickets (Gryllus veletis). Audience type, rearing environment and their interaction were important predictors in all model sets. Thus, audience type may impose different costs and benefits for competing males depending on whether they are socially experienced or not. Our results suggest that field-captured winners, in particular, dynamically adjust their contest behaviour to potentially gain a reproductive benefit via female eavesdropping and may deter future aggression from rivals by advertising their aggressiveness and victories.

Keywords: aggression, audience effect, victory display

1. Introduction

The social environment plays an important role in the evolution of behaviour [1,2]. Many animals engage in signalling contests for territories, resources and mates, and contests often occur within communication networks with several signallers and receivers within range of one another [3]. The communication network model, which highlights the importance of the social environment in which most animals live, expands the scope of studies of contest behaviours, including audience effects [4] and victory displays [5]. Eavesdropping (gaining information from interactions between others [6]) allows audiences to modify their behaviour towards participants and may reduce the costs of mate choice and conflict (injury risk, energy expenditures and lost opportunities [7]). However, an audience may introduce extra costs or benefits to signallers [8]. For example, eavesdropping fish are more likely to initiate aggressive interactions with a loser than a winner [9], imposing immediate costs to the loser. The evolution of traits, such as aggression, whose expression is influenced by interactions with other individuals can be enhanced or inhibited depending on the nature of the social environment [10]. Because contests occur in a social context, our understanding of behavioural strategies and the costs and benefits of conflict will be enhanced if we consider the potential effects of audiences. Audiences may be important not only in influencing individual signallers in interactions, but also as an evolutionary force acting on the form and content of signals [4]. Studies investigating the influence of social environments on behaviour have found audience effects in several contexts [11] but have primarily focused on vertebrates, so the ubiquity of audience effects is not yet known.

Here, we investigate audience effects on aggression and victory display behaviour in an invertebrate, the spring field cricket (Gryllus veletis). Male crickets frequently engage in aggressive contests over resources [12–14]. Winning a contest increases a male's mating success through male–male competition by providing access to mate attraction territories [12] or through female choice for dominant males [15]. Contest winners advertise their success via victory displays using aggressive songs and body jerks [12,14,16–18]. Whether such displays serve to reinforce winner dominance (browbeating) or to communicate victory to mates or rivals (advertising; [5,19]) is unknown. Given that cricket densities can be high [12,20], and mate attraction and contests occur in close proximity [21], contests are likely to occur with female and male audiences nearby. We therefore investigated whether winners' behaviour during and after contests is influenced by the presence and sex of an audience.

The importance of social experience on behaviour has been highlighted in several recent studies [22]. We therefore investigated aggression intensity and victory display behaviour in field-captured and laboratory-reared males to explore the effect of rearing environment on these behaviours. Experience in aggressive contests often influences behaviour during later contests [23]. We predicted that males with social experience would change their aggressive and victory display behaviour depending on the social context, whereas inexperienced laboratory-reared males would be less likely to respond to the presence of an audience.

2. Material and methods

This study was conducted on G. veletis captured in Ottawa, Canada (45°19′ N, 75°40′ W) in spring 2008. We used field-captured and first-generation laboratory-reared adult offspring to investigate the effect of social experience on behaviour. Field-captured males were considered to be socially experienced (although exact levels were unknown) and laboratory-reared crickets lacked social experience. Detailed methods are provided in the electronic supplementary material.

Males participated in one trial per day for 3 consecutive days (one trial per audience type (none, male and female), each with a different opponent). A single audience member was separated from subjects by a transparent wall with small holes to allow transmission of visual and auditory information. Subject males were pre-exposed to the audience individual for 2 min [24], and then a removable opaque partition separating subject opponents was removed.

Thirty-six field-caught males were paired in 54 trials, and 32 laboratory-reared males were paired in 48 trials. For each male, the durations of all agonistic behaviours were tallied and then weighted by aggression level: antennal fencing = one; kick = two; mandible spread, chase, mandible engagement, bite = three and grapple = four [14,18,25]. Trials were terminated when dominance was established, defined as two consecutive retreats by one male [18,25]. We quantified aggression intensity as the sum of aggression scores divided by contest duration for the winner of each trial. Contest winners typically produce victory displays after contests (aggressive stridulation and body jerks, scored as three and one, respectively; [14,17,18]). We calculated victory display scores as the sum of weighted victory display behaviours [25]. See [25] for further details of contest definitions and scoring methods.

We used generalized linear mixed models with male identity and opponent identity as random effects to examine the factors influencing aggression intensity during contests and victory displays after contests. Explanatory variables were audience type, rearing environment, weight difference between opponents and the interaction audience type × rearing environment (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1). We used gamma error structure and log link function because aggression data were right-skewed. We fit models with all combinations of explanatory variables and measured the fit of each model to aggression data with Akaike's information criterion (AIC) scores. We determined the models of best fit and calculated evidence ratios to produce results with intuitive interpretation ([26]; see the electronic supplementary material, methods for details). We performed analyses in SPSS Statistics v. 20.0.0 (IBM, Armonk, USA). Data deposited in the Dryad repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.38n1m [27].

3. Results

Males were aggressive in 78% of trials, and winners performed victory displays after 98% of aggressive contests. Both model sets (aggression intensity and victory displays of winners) shared the same best AIC model (see the electronic supplementary material, tables S2 and S3). Rearing environment and audience type had the highest estimated predictor weights (see the electronic supplementary material, table S4). Model selection revealed that the data were best explained by models that included audience type, rearing environment and the interaction audience × rearing environment (aggression intensity AIC = 217.4, n = 80; victory displays AIC = 203.1, n = 78; electronic supplementary material, tables S5 and S6), although the confidence set for aggression intensity also included the model without the interaction term. Field-captured winners were more aggressive than laboratory-reared winners in the presence of an audience (male or female) but similar in the no audience condition (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Audience type and rearing environment were important predictors of aggression intensity for contest winners (means ± s.e.). Filled bars, field; open bars, laboratory.

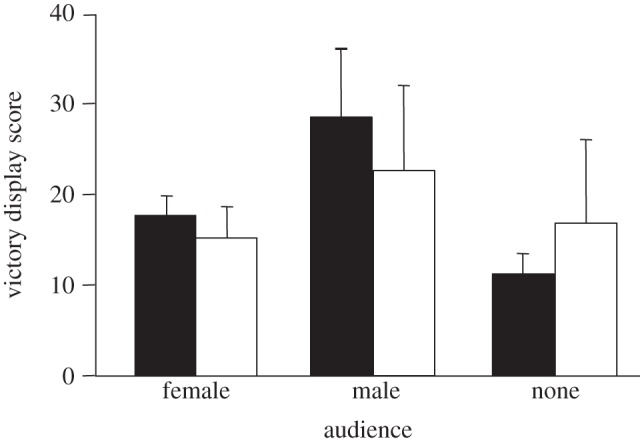

Field-captured winners produced more victory displays in the presence of a male audience compared with no audience, whereas the victory display behaviour of laboratory-reared males was similar across audiences and highly variable among males within audience conditions (figure 2). Field-captured and laboratory-reared males had similar patterns of display within audience conditions. Weight difference between opponents was not heavily weighted in any of the model sets (see the electronic supplementary material, table S4).

Figure 2.

Audience type and rearing environment were important predictors of victory display scores. Filled bars, field; open bars, laboratory.

4. Discussion

We found audience effects on cricket aggressive behaviour that varied across rearing environment (field/laboratory) and behaviour (contest aggression/victory displays). The behaviour of field-captured males was more responsive to the social environment than that of laboratory-reared males; field-captured contest winners were more aggressive in the presence of an audience and produced more victory display behaviour with a male audience than in the no audience treatment. The relative lack of response to audience treatments for laboratory-reared males may reflect a lack of social experience. These findings suggest that experiments on naive laboratory-reared individuals may not accurately reflect the behaviour of wild animals in nature and add to evidence that social experience is important in shaping the development of dynamic behaviours [22]. Field-captured males may be better able to adjust their dynamic behaviours to different social environments after experiencing both their own aggressive encounters and observing interactions between other males. A promising avenue for future research is to carefully control the social experience of laboratory-reared males and examine their aggressive and mating behaviour to better assess the influence of social experience on social behaviours.

Female mating decisions and male fighting decisions may be influenced by information communicated during contests [28], and females may represent a valuable resource for the winner [29], providing selective advantages to elevated aggression by winners during fights. Indeed, we found that contest winners elevate aggression in the presence of a female audience compared with no audience. Contest winners may be selected to produce more aggression and victory displays with male audiences because these displays reduce the likelihood of future contests [19]; victory displays may also advertise additional energy that could be used against potential rivals. It is unknown whether cricket audiences gain information through eavesdropping, but our results suggest potential pay-offs for both victorious males and eavesdroppers.

Our study provides evidence that invertebrates modify aggressive behaviour in the presence of an audience. The ability to perceive an audience and adjust behaviour accordingly is thus not restricted to vertebrates and may be more common across animal taxa than previously recognized. Audiences may also influence signal evolution, potentially driving the evolution of separate signals for public and private information transfer [30] and favouring flexible behavioural strategies (plasticity or bet hedging). For example, aggressive songs used in victory displays may be expected to be louder and lower-pitched than signals used during contests to increase sound transmission and thereby facilitate eavesdropping by nearby individuals [30]. To form biologically relevant models of behaviour and study the evolution of signals and strategies, we must explicitly consider the social environment and incorporate costs and benefits of audiences [31].

Acknowledgements

We thank V. Rook and P. Khazzaka for experimental help and J. Fitzsimmons, R. Gorelick, T. Sherratt, J.-G. Godin, A. Wilson, N. Morehouse and D. Mennill for discussions. NSERC, P.E.O., CFI and Carleton University provided financial support.

References

- 1.Danchin E, Giraldeau L-A, Valone TJ, Wagner RH. 2004. Public information: from nosy neighbors to cultural evolution. Science 305, 487–491 (doi:10.1126/science.1098254) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perrin N, Petit EJ, Menard N. 2012. Social systems: demographics and genetic issues. Mol. Ecol. 21, 443–446 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05404.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGregor PK. 2005. Introduction. In Animal communication networks (ed. McGregor PK.), pp. 1–6 New York, NY: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matos RJ, Schlupp I. 2005. Performing in front of an audience: signalers and the social environment. In Animal communication networks (ed. McGregor PK.), pp. 63–83 New York, NY: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower JL. 2005. The occurrence and function of victory displays within communication networks. In Animal communication networks (ed. McGregor PK.), pp. 114–132 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peake TM. 2005. Eavesdropping in communication networks. In Animal communication networks (ed. McGregor PK.), pp. 13–37 New York, NY: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riechert SE. 1988. The energetic costs of fighting. Am. Zool. 28, 877–884 (doi:10.1093/icb/28.3.877) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zahavi A. 1979. Why shouting? Am. Nat. 113, 155–156 (doi:10.1086/283373) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira RF, McGregor PK, Latruffe C. 1998. Know thine enemy: fighting fish gather information from observing conspecific interactions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 1045–1049 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0397) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore AJ, Brodie ED, Wolf JB. 1997. Interacting phenotypes and the evolutionary process. 1. Direct and indirect genetic effects of social interactions. Evolution 51, 1352–1362 (doi:10.2307/2411187) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plath M, Blum D, Schlupp I, Tiedemann R. 2008. Audience effect alters mating preferences in a livebearing fish, the Atlantic molly, Poecilia mexicana. Anim. Behav. 75, 21–29 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.05.013) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander RD. 1961. Aggressiveness, territoriality, and sexual behavior in field crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllidae). Behaviour 17, 130–223 (doi:10.1163/156853961X00042) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofmann HA, Schildberger K. 2001. Assessment of strength and willingness to fight during aggressive encounters in crickets. Anim. Behav. 62, 337–348 (doi:10.1006/anbe.2001.1746) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang Y, Gerhardt HC, Choe JC. 2008. A comparative study of aggressiveness in eastern North American field cricket species (genus Gryllus). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 62, 1397–1407 (doi:10.1007/s00265-008-0568-6) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simmons LW. 1986. Female choice in the field cricket Gryllus bimaculatus (De Geer). Anim. Behav. 34, 1463–1470 (doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(86)80217-2) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tachon G, Murray AM, Gray DA, Cade WH. 1999. Agonistic displays and the benefits of fighting in the field cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus. J. Insect Behav. 12, 533–543 (doi:10.1023/A:1020970908541) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Logue DM, Abiola I, Raines D, Bailey N, Zuk M, Cade WH. 2010. Does signaling mitigate the cost of agonistic interactions? A test in a cricket that has lost its song. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 2571–2575 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0421) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertram SM, Rook VLM, Fitzsimmons LP. 2010. Strutting their stuff: victory displays in the spring field cricket, Gryllus veletis. Behaviour 147, 1249–1266 (doi:10.1163/000579510X514535) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mesterton-Gibbons M, Sherratt TN. 2006. Victory displays: a game theoretic analysis. Behav. Ecol. 17, 597–605 (doi:10.1093/beheco/ark008) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritz MS, Köhler G. 2007. Male behaviour over the season in a wild population of the field cricket Gryllus campestris L. Ecol. Entomol. 32, 384–392 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2007.00887.x) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodríguez-Muñoz R, Bretman A, Tregenza T. 2011. Guarding males protect females from predation in a wild insect. Curr. Biol. 21, 1716–1719 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.053) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey NW, French N. 2012. Same-sex sexual behaviour and mistaken identity in male field crickets, Teleogryllus oceanicus. Anim. Behav. 84, 1031–1038 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.08.001) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu Y, Earley RL, Wolf LL. 2006. Modulation of aggressive behaviour by fighting experience: mechanisms and contest outcomes. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 81, 33–74 (doi:10.1017/S146479310500686X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matos RJ, McGregor PK. 2002. The effect of the sex of an audience on male–male displays of Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens). Behaviour 139, 1211–1221 (doi:10.1163/15685390260437344) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertram SM, Rook VLM, Fitzsimmons JM, Fitzsimmons LP. 2011. Fine- and broad-scale approaches to understanding the evolution of aggression in crickets. Ethology 117, 1067–1080 (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2011.01970.x) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garamszegi LZ, et al. 2009. Changing philosophies and tools for statistical inferences in behavioral ecology. Behav. Ecol. 20, 1363–1375 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arp137) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzsimmons LP, Bertram SM. 2013. Data from: playing to an audience: the social environment influences aggression and victory displays. Dryad Digital Respository. (doi:10.5061/dryad.38n1m) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mennill DJ, Ratcliffe LM, Boag PT. 2002. Female eavesdropping on male song contests in songbirds. Science 296, 873 (doi:10.1126/science.296.5569.873) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sneddon LU, Huntingford FA, Taylor AC, Clare AS. 2003. Female sex pheromone-mediated effects on behavior and consequences of male competition in the shore crab (Carcinus maenas). J. Chem. Ecol. 29, 55–70 (doi:10.1023/A:1021972412694) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dabelsteen T. 2005. Public, private or anonymous? Facilitating and countering eavesdropping. In Animal communication networks (ed. McGregor PK.), pp. 38–62 New York, NY: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnstone RA. 2001. Eavesdropping and animal conflict. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9177–9180 (doi:10.1073/pnas.161058798). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]