Abstract

Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) variants H3 and H310A1 differ by a single nonconserved amino acid in the VP2 capsid region. C57Bl/6 mice infected with the H3 virus develop myocarditis correlating with activation of T cells expressing the Vγ4 T cell receptor chain. Infecting mice with H310A1 activates natural killer T (NKT; mCD1d-tetramer+ TCRβ+) cells, but not Vγ4 T cells, and fails to induce myocarditis. H310A1 infection preferentially activates M2 alternatively activated macrophage and CD4+FoxP3 (T regulatory) cells, whereas CD4+Th1 (IFN-γ+) cells are suppressed. By contrast, H3 virus infection activates M1 proinflammatory and CD4+Th1 cells, but not T regulatory cells. The M1 macrophage show significantly increased CD1d expression compared to M2 macrophage. The ability of NKT cells to suppress myocarditis was shown by adoptive transfer of purified NKT cells into H3-infected NKT knockout (Jα18 knockout) mice, which inhibited cardiac inflammation and increased T regulatory cell response. Cardiac virus titers were equivalent in all mouse strains indicating that neither Vγ4 nor NKT cells participate in control of virus infection. These data show that NKT and Vγ4 cells cross-regulate T regulatory cell responses during CVB3 infections and are the primary factor determining viral pathogenesis in this mouse model.

Enteroviruses and adenoviruses cause approximately 80% of clinical viral myocarditis in all age groups.1 Cardiac injury results from direct viral injury to infected myocytes and also from host immune responses triggered by the infection.2 Host responses include: i) induction of proinflammatory cytokines [IL-6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)] that suppress myocardial cell contractility3; ii) lysis of infected cardiocytes4; and iii) humoral or cellular autoimmunity to heart antigens, leading to cardiocyte death or dysfunction.5–7 T-cell depletion of mice infected with coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) dramatically reduces animal mortality and cardiac inflammation,8 and heart-specific, autoimmune CD8+ T cells isolated from CVB3-infected mice9 transfer myocarditis into uninfected recipients. Furthermore, immunizing mice with cardiac myosin in adjuvant causes cardiac inflammation closely resembling the virus-induced disease.7,10–12 Several studies demonstrate that induction of autoimmunity in myocarditis corresponds to a decrease in T regulatory cells,13,14 and T regulatory 1 (Tr1) cells making IL-10 are the probable suppressive effectors causing myocarditis resistance in both myosin- and CVB3-induced disease.12,15,16 Recently, studies have shown that γδ T cells activated during pathological CVB3 infections are primarily responsible for preventing T regulatory cell responses and directly kill differentiated CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T regulatory cells through Fas-dependent mechanisms.2,17

Not all CVB3 variants cause myocarditis. Two CVB3 variants, H3 and H310A1, have been cloned and characterized. The H310A1 virus was isolated from the parental H3 virus using a monoclonal antibody to the viral receptor and has a single nonconserved mutation in the VP2 capsid protein in a puff region known for decay accelerating factor (DAF) binding.18 Unlike the highly myocarditic H3 virus, the H310A1 virus is amyocarditic and preferentially activates T regulatory cells16 due to an inability to stimulate γδ T cells during H310A1 virus infections.19 As shown here, although the γδ T cell response is defective in H310A1-infected mice, substantial numbers of natural killer T (NKT) cells are present in the hearts of H310A1-infected, but not H3-infected, animals. This raises the question whether NKT cells promote the generation of T regulatory cells in the myocarditis-resistant animals. This idea is supported by recent studies in which CVB3-infected mice given the NKT ligand, α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer), develop significantly less myocarditis than untreated animals.20 This study found alterations in cytokine environment in the α-GalCer–treated mice but did not investigate the role of T regulatory cells in causing the anti-inflammatory cytokine response.

Although somewhat controversial, various reports indicate that NKT cells suppress autoimmunity or promote tolerance by their effect on T regulatory cell response. Interaction of antigen-presenting cells and NKT cells through CD1d during oral tolerance to nickel results in secretion of IL-4 and IL-10, and activation of T regulatory cells.21–23 Similarly, systemic tolerance could not be established in a mouse model of anterior chamber–associated immune deviation in CD1d knockout (KO) mice unless the animals were transfused with NKT cells and CD1d+ antigen-presenting cells.24 Other studies show that αGalCer, a well-known and specific NKT CD1d-restricted ligand, increases T regulatory cell numbers in vivo25 and can suppress autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice.26–28 Cytokines, such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and IL-10, can be produced by NKT cells,29,30 which could affect dendritic cell cytokine (IL-10) and accessory molecule (CD40, CD80, and/or CD86) expression,31–33 leading to T regulatory cell responses.27,34 Here, studies show that NKT cells activated during H310A1 infection cause the increased T regulatory cell response seen in this model. These experiments show that the nature of the innate immune response following enterovirus infection is crucial in determining autoimmunity induction.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57Bl/6 and C57Bl/6 δ knockout (γδ KO) male mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor ME. C57Bl/6 Jα18 knockout (NKT KO) mice have been described previously35 and were maintained as a breeding colony at the University of Vermont. Male mice were used at 5 to 8 weeks of age. All experiments were reviewed and approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee.

Virus Infection and Titration

The H3 and H310A1 variants of CVB3 have been previously described.18 Adult mice were infected by i.p. injection with 102 plaque-forming units (PFU) of H3 or 104 PFU H310A1 virus in PBS. Animals were sacrificed 7 days after infection. Hearts were removed and then titered using a plaque forming assay.18

Antibodies

Antibodies used in flow cytometry were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). The following antibodies were used: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti–T cell receptor β (TCRβ) (clone H57-597); Pe-Cy5.5 and Alexa 647 anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5); FITC anti-CD8a (clone 53-6.7), PE anti-interferon (IFN)-γ (clone XMG1.2); FITC anti-Vγ4 (clone UC3); PE anti-FoxP3 (clone FJK-16s; eBiosciences, San Diego, CA); PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD69 (clone H1.2F3); FITC or PE anti-CD1d (clone 1B1); Alexa 647 anti-CD11b (clone M1/70); FITC anti–IL-10 (clone JES5-16E3); PE anti–IL-12 (clone C17.8); biotin anti-Ly6C (clone AL-21); PE-Cy7 streptavidin; purified Fc Block (anti-CD16/CD32, clone 2.4G2); Pe-Cy5.5 and Alexa 647 ratIgG2b; APC-Cy7 and PE rat IgG2a (clone R35-95); FITC mouse IgG2a; and FITC and PerCP-Cy5.5 hamster IgG (clone G235-2356). PE mCD1d/PBS57 was supplied by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility at Emory University (Atlanta, GA).

Flow Cytometry

Hearts were perfused with 10 mL of PBS and removed, minced finely, and then digested with 0.4% collagenase II (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as described previously.36 The cells were centrifuged on Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich) for 25 minutes at 325 × g and the lymphocytes removed, washed with PBS, and then resuspended in PBS–1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich) containing Fc Block (dilution 1:100) and the relevant fluorochrome-labeled antibodies as indicated in the text. After incubation on ice for 30 minutes, the cells were washed in PBS-BSA and then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for flow cytometry. Cells were analyzed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) with a single excitation wavelength (488 nm) and band filters for FITC (525 nm), PerCP-Cy5.5 (695/40 nm), and PE (575 nm). The excitation wavelength for Alexa 647 is 643 nm and a band filter of 660/20 nm. The cell population was classified for cell size (forward scatter) and complexity (side scatter). At least 10,000 cells were evaluated. Positive staining was determined relative to isotype controls. To determine the number of individual cell populations, the total number of viable cells was determined by trypan blue exclusion. Following flow cytometry, the percentage of a subpopulation staining with a specific antibody was multiplied by the total number of cells.

Intracellular Cytokine Staining

Details for intracellular cytokine staining have been published previously.37 Spleen cells (1 × 105) were cultured for 4 hours in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, antibiotics, 10 μg/mL of Brefeldin A (BFA) (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 ng/mL phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich), and 500 ng/mL ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were washed in PBS-BSA containing BFA, incubated on ice for 30 minutes in PBS-BSA-BFA containing Fc Block (dilution 1:100) and antibodies to CD11b and Ly6C, CD8, or CD4. The cells were washed once with PBS-BSA-BFA, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes, and then resuspended in PBS-BSA containing 0.5% saponin, Fc Block, and antibodies (dilution 1:100) to either IFN-γ, IL-10, or IL-12, as indicated in the text, for 30 minutes on ice. For FoxP3 staining, cells were labeled with anti-CD4 in PBS–1% BSA containing Fc Block, washed, fixed, and permeabilized with the FoxP3 fixative/permeability buffer set (eBiosciences), then incubated with anti-FoxP3 and Fc Block for 45 minutes at 4°C. The cells were washed and then resuspended in 2% paraformaldehyde.

Isolation of NKT and Vγ4+ Cells

The basic protocol for isolation of innate cells from inflammatory cells infiltrating the hearts of CVB3-infected mice has been published previously.2 Basically, for isolation of Vγ4+ cells, C57Bl/6 mice were infected with H3 virus, and for isolation of NKT cells, C57Bl/6 mice were infected with H310A1 virus. After 7 days, hearts were perfused with 10 mL of PBS, removed, minced finely, and then pressed through increasingly fine mesh screens. The large cellular debris was allowed to settle, and the cell suspension containing the inflammatory cells was layered on Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich) and centrifuged at 300 × g for 25 minutes. The cells at the interface were retrieved, washed in PBS–2% fetal bovine serum, and stained with PE mCD1d-tetramer and FITC anti-TCRβ for NKT cells or with PE anti-Vγ4 and FITC anti-CD69 for Vγ4+ cells. The double-positive cell populations were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting sterile sorting. Cells were either resuspended in PBS, and 0.2 mL containing 0.5 × 104 cells was injected through the tail vein of anesthetized mice, or were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 50 ng/mL PMA, and 500 ng/mL ionomycin for 4 hours at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator to produce supernatant for analysis of cytokine. Some mice also were injected i.p. with 200 μg of monoclonal anti-mouse IL-4 (BD Biosciences) in 0.5 mL of PBS on the same day as injection of virus and NKT cells.

ELISA for Cytokines

Cytokine concentrations in tissue culture supernatants were determined for IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for these mouse cytokines according to the manufacturer's directions (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

Histology

The apical half of the heart was fixed in 10% buffered formalin, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Sections were captured using a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope and Nikon ACT-1 software version 2.65 (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). Images were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop CS5 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) for the percentage of the myocardium inflamed.

Statistics

The nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn's post test was performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.01 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). This statistical analysis was used because the data lacked Gaussian distribution.

Results

Differential Activation of NKT and Vγ4 Cells in H3- and H310A1-Infected C57Bl/6 Mice

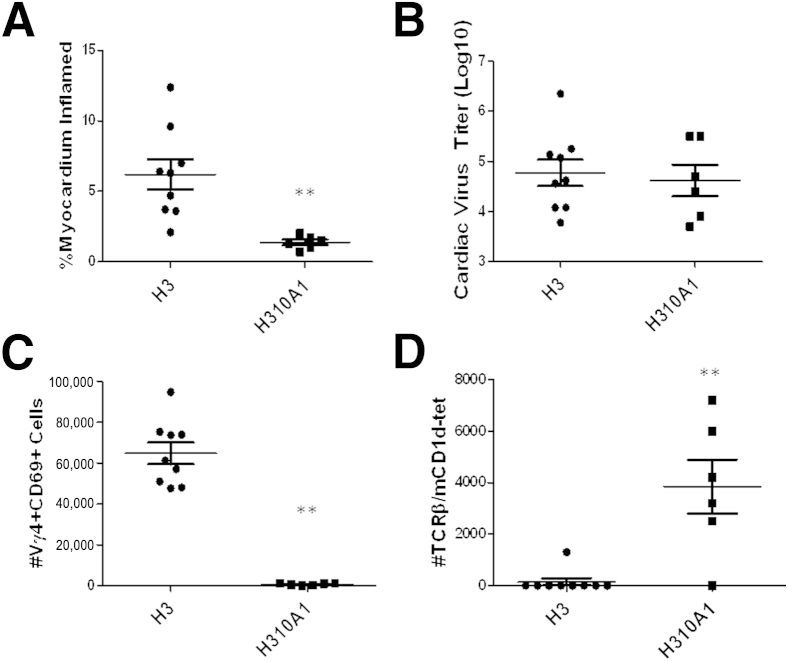

Hearts from uninfected C57Bl/6 mice show no cardiac inflammation or virus by plaque forming assay (data not shown). C57Bl/6 mice were infected with either H3 or H310A1 virus and sacrificed 7 days later. Hearts from individual mice were evaluated for cardiac inflammation (Figure 1A) and cardiac virus titers (Figure 1B). To determine myocarditis, hearts were formalin fixed, paraffin embedded, sectioned, stained with H&E, and evaluated by image analysis as published previously.18 Additional mice were infected, the hearts removed, and the mononuclear cell population retrieved for analysis of T cells expressing TCR Vγ4 and CD69 (early activation marker) (Figure 1C) or were labeled with anti-TCRβ chain and mCD1d-tetramer as indicative of invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells (Figure 1D). There was no significant difference in cardiac virus titers between the groups; however, myocarditis was significantly more severe in H3- than in H310A1-infected mice. As shown previously,38 increased myocarditis in H3-infected animals correlated to substantial numbers of Vγ4+ T cells infiltrating the heart, whereas these cells were absent in H310A1-infected animals. Evaluation of iNKT cell response in CVB3 infection had not been done previously, but the current data show that iNKT cells only infiltrate the heart in H310A1-infected, but not in H3-infected, mice.

Figure 1.

C57Bl/6 male mice infected with either H3 or H310A1 virus. Percentage myocardium inflammation and cardiac virus titer in mice infected with either H3 or H310A1 virus (A and B). Lymphoid cells labeled with antibodies to Vγ4 TCR chain and CD69 early activation marker (C) or with mCD1d-tetramer and antibody to TCRβ for NKT cells (D). Values are given as data from individual mice with means ± SEM indicated for each group. ∗∗P < 0.01 H310A1-infected mice versus H3-infected mice.

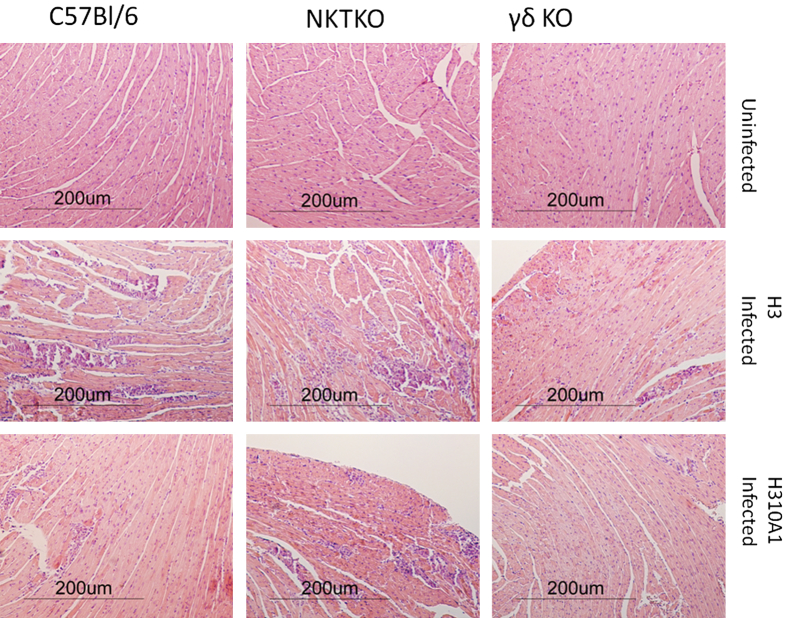

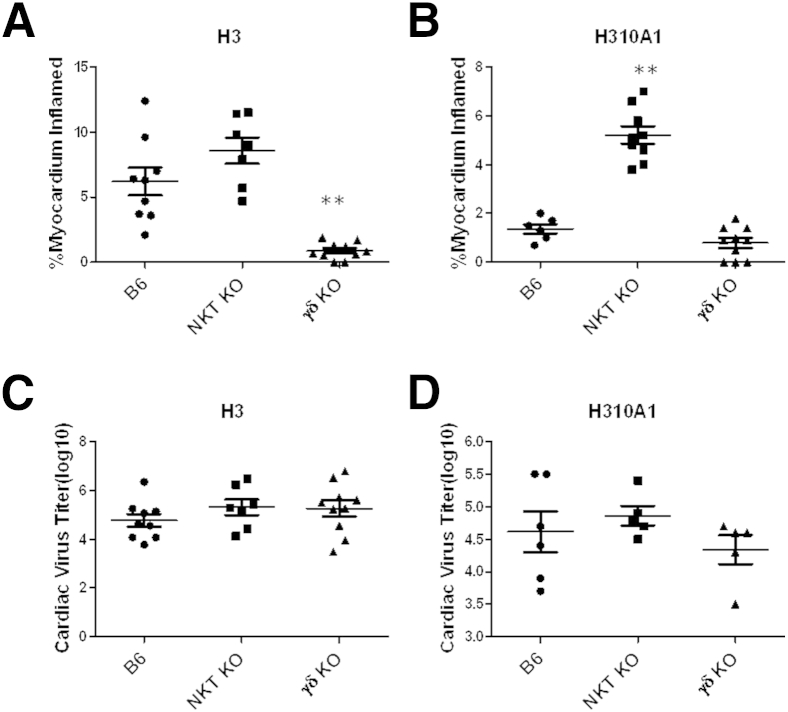

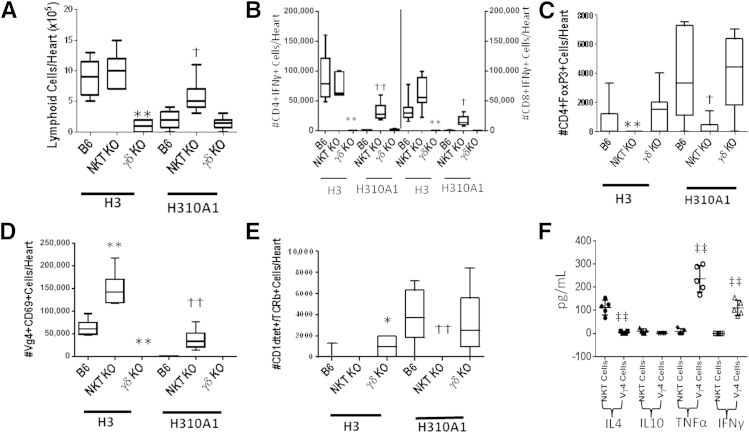

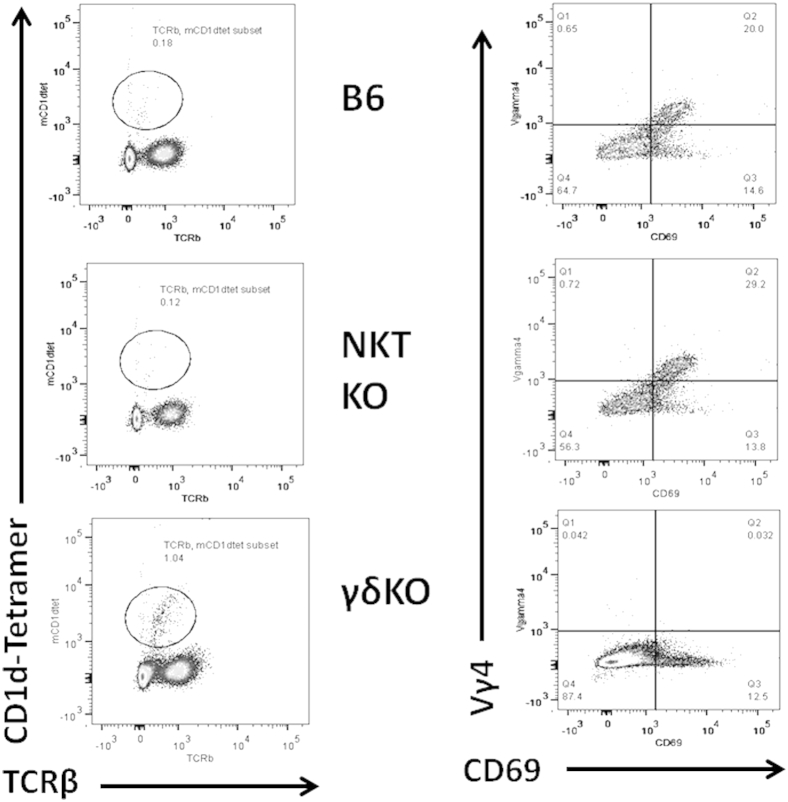

The results shown in Figure 1 give circumstantial evidence that iNKT and Vγ4 cells have distinct roles in myocarditis, with iNKT cells protecting and Vγ4 cells promoting disease. To further confirm the divergent roles for these two innate effector T cells, mice deficient in either cell population (NKT KO or γδ KO) were infected with either H3 or H310A1 virus (Figures 2 and 3). Figure 2 shows the representative histology of hearts from C57Bl/6, NKT KO, and γδ KO mice infected 7 days earlier with either 102 PFU H3 or 104 PFU H310A1 virus. Figure 3A shows the percentage of the myocardium inflamed for all mice in each group and shows that H3 virus induced substantial cardiac inflammation in wild-type and iNKT KO mice, but not in mice lacking γδ T cells, despite statistically equivalent cardiac virus titers in all three groups of mice (Figure 3C). Neither wild-type nor γδ KO mice infected with H310A1 virus showed substantial myocarditis (Figure 3B). However, H310A1 virus infection of iNKT KO mice induced similar levels of cardiac inflammation as observed in H3-infected wild-type mice. Figure 4 shows the various lymphoid cell populations found in the hearts of H3- and H310A1-infected C57Bl/6, NKT KO, and γδ KO mice. In mice developing myocarditis (H3-infected C57Bl/6, H3-infected NKT KO, and H310A1-infected NKT KO mice), increased numbers of total infiltrating lymphoid cells (Figure 4A), CD4+IFN-γ+, and CD8+IFN-γ+ (Figure 4B) and reduced numbers of T regulatory cells (CD4+FoxP3+) (Figure 4C) were found, whereas mice resistant to myocarditis (H3-infected γδ KO, H310A1-infected C57Bl/6, and γδ KO) had reduced T helper 1 (Th1) cells and T regulatory cells. Figure 4, D and E, confirms the absence of Vγ4 and NKT cells in respective γδ KO and iNKT KO mice. One question remained as to what cytokines are expressed by NKT and γδ T cells subsequent to CVB3 infection and whether these cytokines might impact T regulatory cell activation. To address this question, NKT and Vγ4 T cells were isolated by sterile sorting based on CD1d-tetramer/TCRβ double-positive staining (Figure 5) or Vγ4/CD69 double-positive staining and cultured for 4 hours in medium containing PMA/ionomycin but without BFA. The supernatants were isolated and analyzed by ELISA for IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α as these were considered to be the best candidate cytokines mediating positive or negative effects on proinflammatory responses. Figure 4F shows that NKT cells produced significant amounts of IL-4 (105 ± 33 μg/mL), but no other cytokine tested. Vγ4 T cells produced negligible amounts of IL-10 and IL-4 but produced significant amounts of IFN-γ and TNF-α. Representative flow histograms are shown in Figure 5 for Vγ4+ and NKT cell populations.

Figure 2.

Histology of C57Bl/6, NKT KO, or γδ KO 5- to 8-week-old male mice either uninfected or infected 7 days earlier with either 102 PFU H3 or 104 PFU H310A1 virus i.p. Hearts were removed, perfused with PBS, formalin fixed, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and then stained with H&E. Representative examples of histology from each group are provided from the animals reported in Figure 3A.

Figure 3.

C57Bl/6 (B6), NKT KO, and γδ KO mice were infected i.p. with either 102 PFU H3 (A and C) or 104 PFU H310A1 (B and D) virus and sacrificed 7 days later. Hearts were evaluated for myocarditis by image analysis (A and B) and cardiac virus titers by the plaque forming assay (C and D). Values represent individual mice with means ± SEM of each group indicated. ∗∗P < 0.01 infected NKT KO or γδ KO mice versus B6 mice.

Figure 4.

Characterization of infiltrating lymphoid cells in H3- and H310A1-infected mice. Lymphocytes were isolated from hearts of C57Bl/6, NKT KO, or γδ KO mice infected i.p. 7 days earlier with either 102 PFU H3 or 104 PFU H310A1. A: The total infiltrating lymphoid cells isolated from the heart of each individual mouse were determined by trypan blue exclusion. Lymphoid cells from the hearts (105 cells) were stimulated with ionomycin, PMA, and BFA for 4 hours, labeled with either anti-CD4 or anti-CD8, fixed, permeabilized, and then labeled with anti–IFN-γ to demonstrate Th1 cells (B); labeled with anti-CD4, fixed, permeabilized, and labeled with anti-FoxP3 to demonstrate T regulatory cells (C); labeled with anti-Vγ4 and anti-CD69 (D); or labeled with mCD1d-tetramer and anti-TCRβ to demonstrate NKT cells (E). F: Lymphocytes were obtained from hearts of C57Bl/6 mice infected 7 days earlier with either 102 PFU H3 (for Vγ4 cell isolation) or 104 PFU H310A1 (for NKT cell isolation) and labeled with either CD1d-tetramer and antibody to TCRβ (for NKT cells), or with antibody to Vγ4 and CD69 (for Vγ4 cells), and were then subjected to sterile sorting. The indicated cytokine evaluation was performed using commercial kits according to the manufacturer's directions. Values represent the number of the specific cells in the heart-derived lymphoid cell population and were determined by multiplying the percentage of positive cells as determined by flow cytometry multiplied by the number of lymphoid cells isolated from each heart. Values represent means ± SEM of 3 to 8 mice/group. ∗∗P < 0.01 H3-infected NKT KO or γδ KO mice versus H3-infected B6 mice. †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 H310A1-infected NKT KO or γδ KO mice versus H310A1-infected B6 mice. ‡‡P < 0.01 cytokine values for Vγ4 cells versus NKT cells.

Figure 5.

Representative flow histograms of NKT cells as indicated by labeling with mCD1d-tetramer and anti-TCRβ and Vγ4+CD69+ cells in B6, NKT KO, and γδ KO mice infected with H3 virus 7 days earlier.

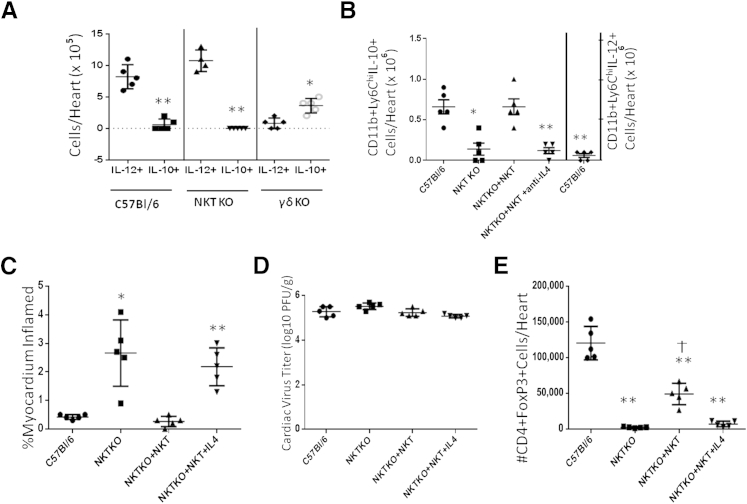

Besides T cells, the other predominant lymphoid cell population found in the heart is the macrophage/monocyte. Analysis of classically activated (inflammatory; M1) and alternatively activated (M2) macrophages was performed by gating on CD11b+Ly6Chi cells and evaluating IL-12 and IL-10 expression by intracellular cytokine staining (Figure 6). When infected with H3 virus, both C57Bl/6 and NKT KO mice showed a polarization toward the M1 macrophage phenotype (CD11b+Ly6ChiIL-12+), whereas γδ KO mice showed polarization toward alternatively activated M2 macrophage (CD11b+Ly6ChiIL-10+) (Figure 6A). When C57Bl/6 mice were infected with H310A1 virus, the number of CD11b+LyChiIL-10+ cells increased (Figure 6B), whereas the number of CD11b+LyChiIL-12+ cells was significantly reduced (Figure 6B). CD11b+LyChiIL-10+ cells in NKT KO mice were also reduced. To confirm that NKT cells are determining M2 macrophage phenotype, NKT cells were isolated by sorting from hearts of H310A1-infected C57Bl/6 mice, and 0.5 × 104 cells were injected i.v. through the tail vein into NKT KO recipients that were infected with H310A1 virus on the same day as cell transfer. An additional group of NKT KO mice given NKT cells was also given 200 μg of monoclonal anti–IL-4 on the same day as NKT cell transfer because this has been shown to reverse the ability of NKT cells to polarize macrophage to the M2 phenotype.39 As shown in Figure 6B, reconstitution of mice with NKT cells increased M2 macrophage infiltrating the heart, but treatment of mice with anti–IL-4 in addition to administration of NKT cells abrogated this effect.

Figure 6.

Macrophage phenotype and innate effector cells. A: C57Bl/6, NKT KO, and γδ KO mice were infected i.p. with 102 PFU H3 virus 7 days earlier, and the lymphoid cells infiltrating the hearts of individual mice were retrieved and evaluated for M1 or M2 macrophage phenotype. The cells were labeled with antibody to CD11b and Ly6C, fixed, permeabilized, and then labeled with antibodies to IL-10 (M2) or IL-12 (M1). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 IL-10+ macrophage versus IL-12+ macrophage. B: C57Bl/6 and NKT KO mice were infected with 104 PFU H310A1 i.p. Groups of infected NKT KO mice also received 0.5 × 104 purified NKT cells i.v. through the tail vein. The NKT cells were isolated by flow sorting of doubly labeled mCD1d-tetramer/anti-TCRβ+ lymphoid cells infiltrating the hearts of C57Bl/6 mice infected 7 days earlier with 104 PFU H310A1 as described in Figure 4 and in Materials and Methods. One group of NKT KO mice given NKT cells also was injected i.p. with 200 μg of monoclonal anti–IL-4. NKT cells and anti–IL-4 were injected on the same day as virus. All mice were sacrificed 7 days later, and lymphoid cells infiltrating the hearts were retrieved and evaluated for CD11b, Ly6Chi, and IL-10 (M2 macrophage) or IL-12 (M1 macrophage, C57Bl/6 only). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus C57Bl/6 IL-10+ cells. Replicate groups of H310A1-infected mice with or without NKT cells and anti–IL-4 as represented in B were evaluated for percent myocardium inflamed (C), cardiac virus titers (D), and number of CD4+FoxP3+ cells/heart (E). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus C57Bl/6 mice. †P < 0.05 versus NKT KO and NKT KO + NKT cells + anti–IL-4 groups. Values represent number of cells in the lymphoid cells from individual mice with the means ± SEM for each group indicated.

Figure 6C shows that C57Bl/6 mice infected with H310A1 virus develop minimal myocarditis, whereas similarly infected NKT KO mice develop increased myocarditis as also shown in Figure 3. Providing NKT KO mice NKT cells abrogated the increase in myocarditis, confirming the protective effect of this population in myocarditis. However, administration of anti–IL-4 in addition to NKT cells again resulted in increased myocarditis. No differences in cardiac virus titers were observed between any of the groups (Figure 6D). The number of CD4+FoxP3+ T regulatory cells isolated from the hearts of the mice generally correlated with myocarditis, because numbers of these immunoregulatory cells were increased in H310A1-infected C57Bl/6 mice and NKT KO mice reconstituted with NKT cells, but not in NKT KO mice or NKT KO + NKT cell–reconstituted animals given anti–IL-4 (Figure 6E). There were significantly fewer T regulatory cells in the latter group than in C57Bl/6 mice despite the fact that both of these groups show minimal myocarditis.

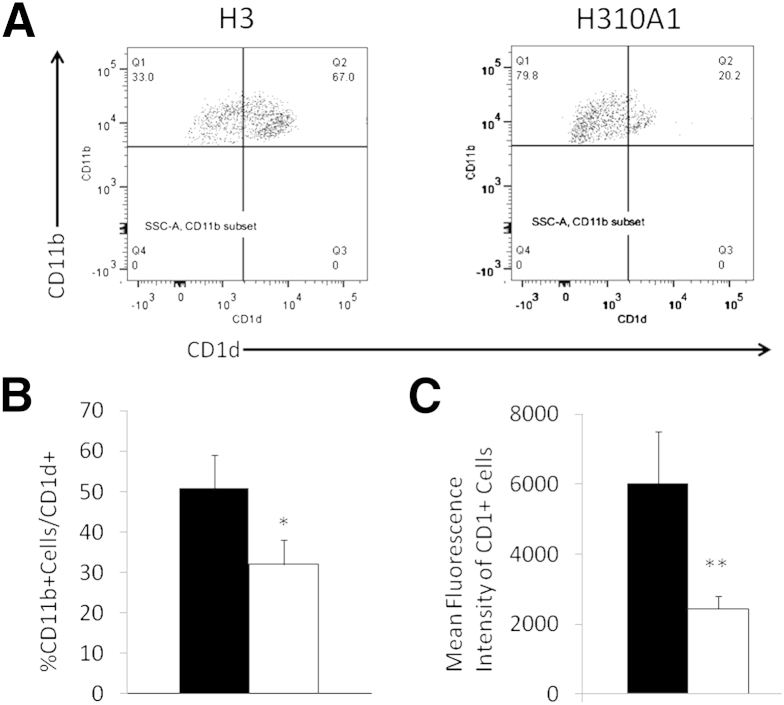

Role of CD1d Expression Levels in NKT and Vγ4+ Cell Activation

Previous studies have shown that H3 infection up-regulates CD1d expression on cardiac myocytes and endothelial cells to a greater extent than H310A1 virus.38 To evaluate the effect of H3 and H310A1 infection on CD1d expression on monocytes, lymphoid cells infiltrating the hearts of H3- and H310A1-infected C57Bl/6 mice were isolated, gated on the CD3-CD11b+ subpopulation, and evaluated for CD1d expression (Figure 7A). Both the percent CD1d+ CD11b+ cells (Figure 7B) and mean fluorescence intensity of CD1d on the CD11b+ cells (Figure 7C) were significantly increased with H3 compared to H310A1 infection.

Figure 7.

CD1d expression on CD11b+ cells isolated from the heart. C57Bl/6 mice were infected 7 days earlier with either H3 or H310A1 virus. Lymphoid cells infiltrating the heart were labeled with antibodies to CD3, CD11b, and CD1d. A: Representative histograms of flow analysis of CD3-CD11b+ cells for CD1d expression. B: Percent CD11b+ cells that are also CD1d+. C: Mean fluorescence intensity of CD1d on CD11b+ cells. Data represent means ± SEM of 4 to 6 mice/group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 H310A1-infected (white bars) mice versus H3-infected (black bars) mice.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate a reciprocal activation pattern between γδ and NKT cells subsequent to infection with two CVB3 variants that differ by a single nonconserved amino acid in a region of the VP2 capsid protein known to bind DAF, one of the two cellular molecules capable of acting as virus receptors.18,40 Although prior studies have shown that the H3 and H310A1 variants of CVB3 are myocarditic and amyocarditic in mice, respectively, and that the poor pathogenicity of the H310A1 variant results from the inability of the virus to activate a subpopulation of γδ T cells expressing the Vγ4 chain,19,38 these studies had not investigated NKT cell responses or the role of these effectors in T regulatory cell activation. A prior publication20 had demonstrated that α-GalCer treatment of CVB3-infected mice protects against myocarditis; causes increases in IFN-γ and IL-4, but decreases in TNF-α, IL-6, MIP2, and MCP-1 expression; and decreased virus replication. Because α-GalCer is accepted as a specific iNKT cell agonist, this study indicated that activation of these innate effectors are potentially protective in myocarditis. However, α-GalCer, derived from sea sponge, is both a highly potent and somewhat artificial activator of NKT cells, and therefore, the study does not prove that NKT cells activated during a specific viral infection would be equally protective. The significance of our findings is that they show that NKT cell activation in the course of a natural CVB3 infection is sufficient to prevent myocarditis; that there is an inverse relationship between activation of two CD1d-specific innate effector cells (NKT and Vγ4+ cells)38,41; that NKT cell response is correlated to activation of the M2 alternatively activated macrophage, whereas Vγ4+ cells correspond to activation of the proinflammatory M1 macrophage; and that NKT cells promote T regulatory cell response, whereas Vγ4+ cells prevent T regulatory cell response. Furthermore, in this model of CVB3 myocarditis, neither Vγ4+ nor NKT cells have a discernible role in controlling virus replication, because cardiac virus titers are equivalent both in NKT KO and γδ KO compared to B6 mice.

A major question raised by these results is why is there such a dramatic difference in γδ and NKT cell responses between H3- and H310A1-infected mice. Despite only a single nonconserved amino acid difference between the two viruses,18 H3 virus basically fails to promote a strong NKT cell response, whereas H310A1 virus does. By contrast, H310A1 infection causes a pronounced NKT cell response even though cardiac virus titers are equivalent to those produced by the H3 virus. The mutated amino acid occurred in a VP2 capsid protein puff region implicated in virus binding to DAF40 and binding avidity of H310A1 to cells is significantly reduced compared to H3 virus using competitive binding assays. DAF is a GPI (glycosylphosphatidylinisotol)-anchored membrane protein and is known to affect T cell activation42,43 although signaling through this molecule is likely to have multiple other effects as well. Many cells in the immune system express DAF, making them all potential targets for virus-induced signaling through this molecule. In fact, because lymphoid cells lack coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR), the other known CVB3 receptor, DAF is the most likely method for infection of most (non–B cell) lymphoid cell populations.44 Antibody cross-linking of DAF on T cells activates protein tyrosine kinases p56lck and p59fyn, early factors in the CD3-TCR pathway.45,46 However, the effect of DAF signaling in antigen-presenting cells may be more relevant because studies indicate that signaling through this molecule alters programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) and CD40 expression,43 and both molecules are known to affect myocarditis susceptibility.47,48 Furthermore, we show that H3 up-regulates CD1d expression on CD11b+ cells much more than H310A1 virus does (Figure 7). CD1d is the target antigen recognized by both NKT and Vγ4 T cells.38,49–52

The effect on CD1d expression on lymphoid cells is consistent with previous studies showing that H3 induces greater CD1d expression in cardiac myocytes and endothelial cells than H310A1.38 These previous studies showed that CVB3 binding to DAF caused rapid calcium flux and activation of nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT), an important transcription factor in inflammation.53 Interestingly, only the H3 or myocarditic variant of CVB3 induced calcium flux or activated NFAT, whereas H310A1, the nonmyocarditic CVB3 variant, failed to stimulate both calcium flux and NFAT translocation. The virus effect and NFAT activation were clearly mediated through DAF because DAF−/− cells failed to respond to H3 virus or activate NFAT although the virus was capable of infecting DAF−/− cells. The demonstration that CVB3 could infect DAF−/− cells was unexpected because, presumably, CAR, the other major CVB3 receptor, is not expressed by lymphoid cells. This observation was not followed up but indicates that CAR is in fact expressed on these cells or that other virus receptors exist on lymphoid cells. Nonetheless, up-regulation of CD1d depended on calcium signaling and NFAT translocation, and this specific aspect of DAF signaling is undoubtedly responsible for modulation of CD1d expression subsequent to H3 infection.

Because alterations in costimulatory molecule expression on dendritic cells have been shown to promote tolerance,54,55 it is highly likely that differences in H3 and H310A1 binding avidity to DAF alters both costimulatory molecule and CD1d expression in antigen-presenting cells, leading to the difference in T regulatory cell activation. The relative expression levels of CD1d may also be important. Although both NKT and Vγ4 T cells recognize CD1d, there is no evidence that these two innate effectors are activated by the same threshold of CD1d expression. One potential explanation for the difference in innate response between H3 and H310A1 infections would be that NKT cells can be activated at lower CD1d expression levels than Vγ4 cells. In this case, the lower CD1d expression observed during H310A1 infections would be adequate to activate NKT cells but would be insufficient to activate Vγ4 cells. Only infections resulting in quite high CD1d expression patterns would stimulate the Vγ4 effectors and once activated, these effectors might down-regulate or otherwise negate the immunomodulatory effects of the NKT cells. Whether this hypothesis is relevant will require further investigation. One surprising observation was that the number of T regulatory cells recoverable from the hearts of NKT KO mice given NKT cells was significantly less than that from C57Bl/6 mice (Figure 6E) despite the fact that myocarditis in both groups was equivalent (Figure 6C). The two likely explanations for this finding are that a minimal number of T regulatory cells are needed to inhibit cardiac inflammation, and once that threshold number is reached, any more T regulatory cells will not further suppress inflammation; or there are other immunoregulatory factors in H310A1-infected NKT KO + NKT cell–treated mice besides T regulatory cells, which suppress myocarditis.

Acknowledgments

The PE-conjugated mCD1d tetramer was kindly supplied by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility (Yerkes) at Emory University (Atlanta, GA). We also thank Colette Charland and Roxana Del Rio Guerra for help with flow cytometry and Pamela Burton for help in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants HL108371 (S.A.H.), HL093604 (S.A.H.), HL086549 (S.A.H.), AI067897 (J.E.B.), and P20 GM103496-07 (S.A.H. and J.E.B), and the National Science Foundation of China (30800481 to W.L.) from the People's Republic of China.

References

- 1.Bowles N.E., Ni J., Kearney D.L., Pauschinger M., Schultheiss H.P., McCarthy R., Hare J., Bricker J.T., Bowles K.R., Towbin J.A. Detection of viruses in myocardial tissues by polymerase chain reaction. evidence of adenovirus as a common cause of myocarditis in children and adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:466–472. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00648-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huber S. γδ T lymphocytes kill T regulatory cells through CD1d. Immunology. 2010;131:202–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman G., Colston J., Zabalgoitia M., Chandrasekar B. Contractile depression and expression of proinflammatory cytokines and iNOS in viral myocarditis. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H249–H258. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.1.H249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maisch B., Bauer E., Cirsi M., Kocksiek K. Cytolytic cross-reactive antibodies directed against the cardiac membrane and viral proteins in coxsackievirus B3 and B4 myocarditis. Circulation. 1993;87(Suppl IV):49–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairweather D., Kaya Z., Shellam G.R., Lawson C.M., Rose N.R. From infection to autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2001;16:175–186. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2000.0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fairweather D., Frisancho-Kiss S., Rose N.R. Viruses as adjuvants for autoimmunity: evidence from Coxsackievirus-induced myocarditis. Rev Med Virol. 2005;15:17–27. doi: 10.1002/rmv.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y., Heuser J.S., Cunningham L.C., Kosanke S.D., Cunningham M.W. Mimicry and antibody-mediated cell signaling in autoimmune myocarditis. J Immunol. 2006;177:8234–8240. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodruff J., Woodruff J. Involvement of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of coxsackievirus B3 heart disease. J Immunol. 1974;113:1726–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guthrie M., Lodge P.A., Huber S.A. Cardiac injury in myocarditis induced by Coxsackievirus group B, type 3 in Balb/c mice is mediated by Lyt 2 + cytolytic lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 1984;88:558–567. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Afanasyeva M., Georgakopoulos D., Rose N.R. Autoimmune myocarditis: cellular mediators of cardiac dysfunction. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:476–486. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaya Z., Afanasyeva M., Wang Y., Dohmen K.M., Schlichting J., Tretter T., Fairweather D., Holers V.M., Rose N.R. Contribution of the innate immune system to autoimmune myocarditis: a role for complement. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:739–745. doi: 10.1038/90686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaya Z., Dohmen K.M., Wang Y., Schlichting J., Afanasyeva M., Leuschner F., Rose N.R. Cutting edge: a critical role for IL-10 in induction of nasal tolerance in experimental autoimmune myocarditis. J Immunol. 2002;168:1552–1556. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Job L.P., Lyden D.C., Huber S.A. Demonstration of suppressor cells in coxsackievirus group B, type 3 infected female Balb/c mice which prevent myocarditis. Cell Immunol. 1986;98:104–113. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(86)90271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisancho-Kiss S., Davis S.E., Nyland J.F., Frisancho J.A., Cihakova D., Barrett M.A., Rose N.R., Fairweather D. Cutting edge: cross-regulation by TLR4 and T cell Ig mucin-3 determines sex differences in inflammatory heart disease. J Immunol. 2007;178:6710–6714. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S., Liu J., Wang M., Zhang J., Wang Z. Treatment and prevention of experimental autoimmune myocarditis with CD28 superagonists. Cardiology. 2010;115:107–113. doi: 10.1159/000256660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber S.A., Feldman A.M., Sartini D. Coxsackievirus B3 induces T regulatory cells, which inhibit cardiomyopathy in tumor necrosis factor-alpha transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2006;99:1109–1116. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000249405.13536.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber S.A. Depletion of gammadelta+ T cells increases CD4+ FoxP3 (T regulatory) cell response in coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. Immunology. 2009;127:567–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowlton K.U., Jeon E.S., Berkley N., Wessely R., Huber S. A mutation in the puff region of VP2 attenuates the myocarditic phenotype of an infectious cDNA of the Woodruff variant of coxsackievirus B3. J Virol. 1996;70:7811–7818. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7811-7818.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huber S.A., Sartini D., Exley M. Vgamma4(+) T cells promote autoimmune CD8(+) cytolytic T-lymphocyte activation in coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis in mice: role for CD4(+) Th1 cells. J Virol. 2002;76:10785–10790. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10785-10790.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu C.Y., Feng Y., Qian G.C., Wu J.H., Luo J., Wang Y., Chen G.J., Guo X.K., Wang Z.J. alpha-Galactosylceramide protects mice from lethal Coxsackievirus B3 infection and subsequent myocarditis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;162:178–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khovidhunkit W., Kim M.S., Memon R.A., Shigenaga J.K., Moser A.H., Feingold K.R., Grunfeld C. Effects of infection and inflammation on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism: mechanisms and consequences to the host. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1169–1196. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R300019-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roelofs-Haarhuis K., Wu X., Gleichmann E. Oral tolerance to nickel requires CD4+ invariant NKT cells for the infectious spread of tolerance and the induction of specific regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:1043–1050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roelofs-Haarhuis K., Wu X., Nowak M., Fang M., Artik S., Gleichmann E. Infectious nickel tolerance: a reciprocal interplay of tolerogenic APCs and T suppressor cells that is driven by immunization. J Immunol. 2003;171:2863–2872. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sonoda K.H., Exley M., Snapper S., Balk S.P., Stein-Streilein J. CD1-reactive natural killer T cells are required for development of systemic tolerance through an immune-privileged site. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1215–1226. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.9.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.La Cava A., Van Kaer L., Fu-Dong-Shi CD4+CD25+ Tregs and NKT cells: regulators regulating regulators. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monteiro M., Almeida C.F., Caridade M., Ribot J.C., Duarte J., Agua-Doce A., Wollenberg I., Silva-Santos B., Graca L. Identification of regulatory Foxp3+ invariant NKT cells induced by TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2010;185:2157–2163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen G., Han G., Wang J., Wang R., Xu R., Shen B., Qian J., Li Y. Natural killer cells modulate overt autoimmunity to homeostasis in nonobese diabetic mice after anti-CD3 F(ab′)2 antibody treatment through secreting transforming growth factor-beta. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1086–1094. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salio M., Speak A.O., Shepherd D., Polzella P., Illarionov P.A., Veerapen N., Besra G.S., Platt F.M., Cerundolo V. Modulation of human natural killer T cell ligands on TLR-mediated antigen-presenting cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20490–20495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710145104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonoda K.H., Faunce D.E., Taniguchi M., Exley M., Balk S., Stein-Streilein J. NK T cell-derived IL-10 is essential for the differentiation of antigen-specific T regulatory cells in systemic tolerance. J Immunol. 2001;166:42–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein-Streilein J., Sonoda K.H., Faunce D., Zhang-Hoover J. Regulation of adaptive immune responses by innate cells expressing NK markers and antigen-transporting macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:488–494. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuirk P., Mills K.H. Pathogen-specific regulatory T cells provoke a shift in the Th1/Th2 paradigm in immunity to infectious diseases. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:450–455. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumanogoh A., Wang X., Lee I., Watanabe C., Kamanaka M., Shi W., Yoshida K., Sato T., Habu S., Itoh M., Sakaguchi N., Sakaguchi S., Kikutani H. Increased T cell autoreactivity in the absence of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions: a role of CD40 in regulatory T cell development. J Immunol. 2001;166:353–360. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salomon B., Lenschow D.J., Rhee L., Ashourian N., Singh B., Sharpe A., Bluestone J.A. B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 2000;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bach J.F., Bendelac A., Brenner M.B., Cantor H., De Libero G., Kronenberg M., Lanier L.L., Raulet D.H., Shlomchik M.J., von Herrath M.G. The role of innate immunity in autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1527–1531. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui J., Shin T., Kawano T., Sato H., Kondo E., Toura I., Kaneko Y., Koseki H., Kanno M., Taniguchi M. Requirement for Valpha14 NKT cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science. 1997;278:1623–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huber S., Sartini D. T cells expressing the Vgamma1 T-cell receptor enhance virus-neutralizing antibody response during coxsackievirus B3 infection of BALB/c mice: differences in male and female mice. Viral Immunol. 2005;18:730–739. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber S., Graveline D., Born W., O'Brien R. Cytokine production by Vgamma+ T cell subsets is an important factor determining CD4+ Th cell phenotype and susceptibility of BALB/c mice to coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. J Virol. 2001;75:5860–5868. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.5860-5869.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huber S., Sartini D., Exley M. Role of CD1d in coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. J Immunol. 2003;170:3147–3153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denney L., Kok W.L., Cole S.L., Sanderson S., McMichael A.J., Ho L.P. Activation of invariant NKT cells in early phase of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis results in differentiation of Ly6Chi inflammatory monocyte to M2 macrophages and improved outcome. J Immunol. 2012;189:551–557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergelson J.M., Mohanty J.G., Crowell R.L., St John N.F., Lublin D.M., Finberg R.W. Coxsackievirus B3 adapted to growth in RD cells binds to decay-accelerating factor (CD55) J Virol. 1995;69:1903–1906. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1903-1906.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Durante-Mangoni E., Wang R., Shaulov A., He Q., Nasser I., Afdhal N., Koziel M.J., Exley M.A. Hepatic CD1d expression in hepatitis C virus infection and recognition by resident proinflammatory CD1d-reactive T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:2159–2166. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vieyra M., Leisman S., Raedler H., Kwan W.H., Yang M., Strainic M.G., Medof M.E., Heeger P.S. Complement regulates CD4 T-cell help to CD8 T cells required for murine allograft rejection. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:766–774. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fang C., Miwa T., Song W.C. Decay-accelerating factor regulates T-cell immunity in the context of inflammation by influencing costimulatory molecule expression on antigen-presenting cells. Blood. 2011;118:1008–1014. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarasch-Althof N., Wiesener N., Schmidtke M., Wutzler P., Henke A. Antibody-dependent enhancement of coxsackievirus B3 infection of primary CD19+ B lymphocytes. Viral Immunol. 2010;23:369–376. doi: 10.1089/vim.2010.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shenoy-Scaria A.M., Kwong J., Fujita T., Olszowy M.W., Shaw A.S., Lublin D.M. Signal transduction through decay-accelerating factor. Interaction of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchor and protein tyrosine kinases p56lck and p59fyn 1. J Immunol. 1992;149:3535–3541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tosello A.C., Mary F., Amiot M., Bernard A., Mary D. Activation of T cells via CD55: recruitment of early components of the CD3-TCR pathway is required for IL-2 secretion. J Inflamm. 1998;48:13–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seko Y., Yagita H., Okumura K., Azuma M., Nagai R. Roles of programmed death-1 (PD-1)/PD-1 ligands pathway in the development of murine acute myocarditis caused by coxsackievirus B3. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bo H., Zhenhu L., Lijian Z. Blocking the CD40-CD40L interaction by CD40-Ig reduces disease progress in murine myocarditis induced by CVB3. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2010;19:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boyson J.E., Rybalov B., Koopman L.A., Exley M., Balk S.P., Racke F.K., Schatz F., Masch R., Wilson S.B., Strominger J.L. CD1d and invariant NKT cells at the human maternal-fetal interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13741–13746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162491699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Exley M.A., Hou R., Shaulov A., Tonti E., Dellabona P., Casorati G., Akbari O., Akman H.O., Greenfield E.A., Gumperz J.E., Boyson J.E., Balk S.P., Wilson S.B. Selective activation, expansion, and monitoring of human iNKT cells with a monoclonal antibody specific for the TCR alpha-chain CDR3 loop. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1756–1766. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smiley S.T., Lanthier P.A., Couper K.N., Szaba F.M., Boyson J.E., Chen W., Johnson L.L. Exacerbated susceptibility to infection-stimulated immunopathology in CD1d-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2005;174:7904–7911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas S.Y., Hou R., Boyson J.E., Means T.K., Hess C., Olson D.P., Strominger J.L., Brenner M.B., Gumperz J.E., Wilson S.B., Luster A.D. CD1d-restricted NKT cells express a chemokine receptor profile indicative of Th1-type inflammatory homing cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:2571–2580. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huber S.A., Rincon M. Coxsackievirus B3 induction of NFAT: requirement for myocarditis susceptibility. Virology. 2008;381:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu L., Thomson A.W. Manipulation of dendritic cells for tolerance induction in transplantation and autoimmune disease. Transplantation. 2002;73:S19–S22. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200201151-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baev D.V., Caielli S., Ronchi F., Coccia M., Facciotti F., Nichols K.E., Falcone M. Impaired SLAM-SLAM homotypic interaction between invariant NKT cells and dendritic cells affects differentiation of IL-4/IL-10-secreting NKT2 cells in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:869–877. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]