Abstract

Three field populations of Cx. pipiens (L.) mosquitoes were collected from three different localities in Riyadh city. They were tested for developing resistance against commonly used insecticides to control mosquitoes in Riyadh. Two populations from Wadi Namar (WN1 and WN2) were highly resistant to deltamethrin (187.1- and 161.4-folds respectively). The field population from AL-Wadi district (AL-W) showed low resistance to lambda-cyhalothrin (3.8-folds) and moderate resistance to beta-cyfluthrin and bifenthrin (14- and 38.4-folds respectively). No resistance to fenitrothion was observed in WN1 population. Fenitrothion concentrations required to inhibit 50% of Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in both WN1 population and the laboratory susceptible strain (S-LAB) were 0.073 and 0.078 ppm respectively. Piperonyl butoxide suppressed resistance to pyrethroid insecticides (>90%) in field populations indicating that oxidases and/or esterases play an important role in the reduction of pyrethroids toxicity. These results should be considered in the current mosquitoes control programs in Riyadh.

Keywords: Resistance, Cx. pipiens, Pyrethroids, Synergism, Piperonyl butoxide, Saudi Arabia

1. Introduction

The mosquito acts as one of the most important vectors of some human diseases. The major vectors are members of the Culex, Aedes and Anopheles genera. All these genera are found in Saudi Arabia (Büttiker, 1981; Hemingway et al., 1990; Abdullah and Merdan, 1995; Jupp et al., 2002; El-Khereji, 2005; Al-Ghamdi et al. 2008). Cx. pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) populations are found worldwide and they transmit many serious pathogens (i.e. filariasis, West Nile virus and others) to man and his domestic animals (Eldridge et al., 2000; Vingradova, 2000; Turell et al., 2001; CDC, 2002; Cui et al., 2006; Kasai et al., 2008). In Saudi Arabia, Cx. pipiens is abundant in Riyadh region (Alahmed and Kheir, 2005; El-Khereji, 2005; Alahmed et al., 2007; El-Khereji et al., 2007), and it was found to be potential vector of bancroftian filariasis (Omer, 1996).

Pyrethroid and organophosphate insecticides are used extensively to control disease vectors (Berman, 2001; Al-Sarar et al., 2005; Hardstone et al., 2006; Daaboub et al., 2008). However, mosquitoes developed resistance to all insecticide classes (Hemingway et al., 1990; Peiris and Hemingway, 1990; Bissat et al., 1997; Xu et al., 2005). Insecticide resistance is the main cause for the failure of control programs aiming to eradicate disease vectors (WHO, 1976). The appearance of Rift Valley fever in 2000 (Jupp et al., 2002) and Dengue fever in 2004 (Ayyub et al., 2006) in Saudi Arabia led to extensive application of insecticides to combat all mosquito species. This action initiates insect resistance and accelerates the level of developed resistance. Therefore, this work was conducted to detect insecticide resistance in Cx. pipiens field populations in Riyadh City, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mosquitoes

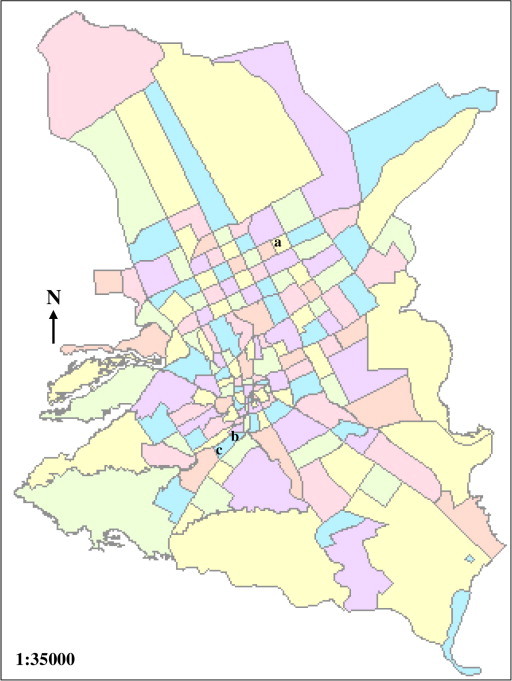

Laboratory strain of Cx. pipiens (S-LAB) was obtained from the High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt and maintained in our laboratory for more than seven years. Field populations of Cx. pipiens complex were collected, as egg-rafts, from one location (a) at the north in AL-Wadi district (AL-W strain) and from 2 locations (b and c) in Wadi Namar south of Riyadh for WN1 and WN2 strains, respectively as shown in Fig. 1. Collected eggs were allowed to hatch under laboratory conditions and the hatched larvae were fed on mouse feed until they reached the late 3rd and early 4th larval instars.

Figure 1.

Map of Riyadh, locations of Cx. pipiens field populations collection: (a) Al-Wadi and (b and c) Wadi Namar.

2.2. Insecticides

Fenvalerate (Etenax 20% EC; APCO Co. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). deltamethrin (K-Othrine EC15; BAYER Environmental Science SAS. France), lambda-cyhalothrin (Icon 2.5 EC; BAYER Environmental Science SAS. France). beta-cyfluthrin (Scidco-Beta 25% EC; SCIDCO Co. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) and bifenthrin (Bifentor 2.5% EC; APCO Co. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), fenitrothion (Scidco Residual 50% EC; SCIDCO Co. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). All insecticides were obtained from Riyadh municipality, department of health protection. Piperonyl butoxide (PBO) was a gift from SCIDCO Co., Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

2.3. Larval bioassay

The efficacy of the selected insecticides against tested mosquito strains was tested according to Al-Sarar et al. (2005). Twenty mosquito larvae were placed in 200 ml glass beaker containing 100 ml of distilled water. A serial of test concentrations, dissolved in ethanol, were added to give the aimed final concentrations and stirred quietly with a glass rod. Each concentration was triplicated. Three beakers served as control received only the solvent. One ppm of PBO was added to all synergized treatments. Dead larvae were counted 24 and 48 h after treatment; larvae that did not move when touched with a thin needle were considered dead.

2.4. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity

AChE activity in whole larvae was estimated according to the procedure described by Ellman et al. (1961). Field strain was treated with different concentrations of fenitrothion for 150 min, control larvae were treated with solvent only. Control and treated larvae were homogenized with cold phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 8). The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was decanted, kept on ice and used as the crude enzyme preparation. In 10 ml glass test tubes 100 μl of the crude enzyme was added to 2.8 ml of phosphate buffer (pH 8) and 100 μl DTNB (0.01 M in phosphate buffer, pH 7) was added; the reaction was initiated with the addition of 30 μl of ATChI (75 mM). Absorbance was recorded at 412 nm after 10 min using a Shimadzu UV-1201 spectrophotometer. Blank contained the same components except the substrate. AChE activity was estimated, using the extinction coefficient of 13,600 M−1 cm−1 for the 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate anion. Each treatment was replicated 2×. Protein content was determined in whole larval homogenate by the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

2.5. Data analysis

Mortality percentages were determined and corrected using Abbott’s formula (1925). Data were analyzed using Ldp line program based on Finney (1971). Values of LC50, LC95, confidence limits at 95% and slopes were computed. Resistance ratio at LC50 (RR50 = LC50 of field population/LC50 of S-LAB) and synergism ratio at LC50 (SR50 = LC50 in absence of PBO/LC50 in presence of PBO) were calculated. The percent of resistance suppression by PBO was calculated according to the equation of Thomas et al. (1991) which is: resistance suppression (%) = [1 − (LC50 in presence of PBO/LC50 in absence of PBO)] * 100.

3. Results

Toxicity of fenvalerate and deltamethrin to laboratory and field populations of Cx. pipiens, synergistic effect of PBO and resistance level of field populations are presented in Table 1. LC50 values of fenvalerate against S-LAB, WN1 and WN2 populations were 0.0049, 0.015 and 0.019 ppm respectively. Field populations WN1 and WN2 exhibited tolerance to fenvalerate with low RR50 of 3.06 and 3.9 folds. The addition of PBO increased the toxicity by 19.7-folds for WN1 (LC50 = 0.00076 ppm) and 10.5 times for WN2 (LC50 = 0.0018 ppm). Consequently, resistance status in field populations were reduced and RR50 values were 0.15 and 0.37 for WN1 and WN2, respectively, with suppression of resistance by 95% and 91%, respectively. Deltamethrin was more toxic than fenvalerate to S-LAB (LC50 = 0.0007 ppm); however, it was less toxic to both WN1 and WN2 with LC50 values of 0.131 and 0.113 ppm. High level of resistance was recorded for WN1 (187.1-folds) and for WN2 (161.4-folds). Resistance level was reduced to 14.3- and 4.3-folds for WN1 and WN2 when PBO was added, with resistance suppression of 93% and 98% respectively. PBO synergized deltamethrin toxicity against WN1 and WN2 populations (Table 1) by 13.1 and 37.7 times, respectively.

Table 1.

Toxicity of fenvalerate and deltamethrin to Cx. pipiens and synergistic effect of piperonyl butoxide.

| Insecticide | Strain | LC50 ppm (95% CL) | LC95 ppm (95% CL) | Slope ± SE | RR50 | SR50 | RS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fenvalerate | S-LAB | 0.0049 (0.0035–0.0062) | 0.046 (0.028–0.119) | 1.689 ± 0.287 | |||

| WN1 | 0.015 (0.014–0.017) | 0.042 (0.033–0.05) | 3.96 ± 0.213 | 3.06 | |||

| WN2 | 0.019 (0.016–0.023) | 0.16 (0.11–0.24) | 1.8 ± 0.034 | 3.9 | |||

| Fenvalerate + PBO | WN1 | 0.00076 (0.00065–0.0009) | 0.004 (0.003–0.005) | 2.28 ± 0.047 | 0.15 | 19.7 | 95 |

| WN2 | 0.0018 (0.0015–0.0021) | 0.011 (0.0075–0.016) | 2.1 ± 0.05 | 0.37 | 10.5 | 91 | |

| Deltamethrin | S-LAB | 0.0007 (0.0005–0.0009) | 0.0066 (0.004–0.019) | 1.683 ± 0.302 | |||

| WN1 | 0.131 (0.121–0.142) | 0.262 (0.226–0.304) | 5.44 ± 0.245 | 187.1 | |||

| WN2 | 0.113 (0.096–0.133) | 0.63 (0.39–1.04) | 2.21 ± 0.103 | 161.4 | |||

| Deltamethrin + PBO | WN1 | 0.01 (0.009–0.011) | 0.032 (0.024–0.043) | 3.2 ± 0.193 | 14.3 | 13.1 | 93 |

| WN2 | 0.003 (0.0024–0.0048) | 0.049 (0.025–0.098) | 1.35 ± 0.03 | 4.3 | 37.7 | 98 |

RR50, resistance ratio at LC50 (RR50 = LC50 of field population/LC50 of S-LAB); SR50, synergism ratio (SR50 = LC50 in absence of PBO/LC50 in presence of PBO); RS (%), resistance suppression % (RS (%) = [1 − (LC50 in presence of PBO/LC50 in absence of PBO)] * 100).

LC50 values of beta-cyfluthrin against S-LAB and AL-W strains 24 h post-treatment were 0.0053 and 0.074 ppm, respectively, with RR50 equal to 14 folds (Table 2). PBO reduced the LC50 of beta-cyfluthrin to 0.0049 ppm (RR50 = 0.92). Lambda-cyhalothrin was the most toxic insecticide to both S-LAB and AL-W strains with LC50 values of 0.0017 and 0.0065 ppm, respectively. AL-W strain was tolerant to lambda-cyhalothrin with RR50 equal to 3.8. Addition of PBO increased the toxicity by 16.2-folds (LC50 = 0.0004 ppm, RR50 = 0.23). PBO suppressed the resistance to both beta-cyfluthrin and lambda-cyhalothrin by 94%. Bifenthrin LC50 values were 0.0087 ppm for S-LAB and 0.334 ppm for AL-W strains. The highest resistance status of AL-W strain was to bifenthrin (RR50 = 38.4). PBO increased the toxicity of bifenthrin by 45.7-folds (LC50 = 0.0073 ppm, RR50 = 0.84 and RS = 98%).

Table 2.

Toxicity of some pyrethroid insecticides to Cx. pipiens after 24 h of exposure.

| Insecticide | Strain | LC50 ppm (95%CL) | LC95 ppm (95%CL) | Slope ± SE | RR50 | SR50 | RS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-cyfluthrin | S-LAB | 0.0053 (0.0039–0.0072) | 0.936 (0.331–4.903) | 0.731 ± 0.088 | |||

| AL-W | 0.074 (0.059–0.098) | 0.293 (0.233–0.5) | 7.763 ± 0181 | 14 | |||

| Beta-cyfluthrin + PBO | AL-W | 0.0049 (0.0035–0.007) | 1.626 (0.471–12.988) | 0.653 ± 0.086 | 0.92 | 15.1 | 94 |

| Lambda-cyhalothrin | S-LAB | 0.0017 (0.0014–0.002) | 0.021 (0.014–0.039) | 1.483 ± 0.135 | |||

| AL-W | 0.0065 (0.0057–0.0075) | 0.034 (0.025–0.052) | 2.309 ± 0.224 | 3.8 | |||

| Lambda-cyhalothrin + PBO | AL-W | 0.0004 (0.0003–0.0004) | 0.0025 (0.0018–0.0039) | 1.985 ± 0.18 | 0.23 | 16.2 | 94 |

| Bifenthrin | S-LAB | 0.0087 (0.0072–0.011) | 0.115 (0.072–0.22) | 1.466 ± 0.129 | |||

| AL-W | 0.334 (0.223–0.532) | 1.89 (1.305–4.737) | 2.186 ± 0.149 | 38.4 | |||

| Bifenthrin + PBO | AL-W | 0.0073 (0.0015–0.015) | 1.184 (0.489–8.651) | 0.744 ± 0.152 | 0.84 | 45.7 | 98 |

RR50, resistance ratio at LC50 (RR50 = LC50 of field population/LC50 of S-LAB); SR50, synergism ratio (SR50 = LC50 in absence of PBO/LC50 in presence of PBO); RS (%), resistance suppression % (RS (%) = [1 − (LC50 in presence of PBO/LC50 in absence of PBO)] * 100).

The same parameters reported in Table 2 are shown in Table 3 with values obtained 48 h post-treatment. LC50 values of beta-cyfluthrin against S-LAB and AL-W strains were 0.0028 and 0.069 ppm, respectively exhibiting lower values than that estimated after 24 h of treatment (RR50 = 24.6). PBO reduced RR50 to 1 and LC50 to 0.0028 ppm. Lambda-cyhalothrin was the most toxic one with LC50 values 0.0011 and 0.0045 ppm against S-LAB and AL-W populations, respectively. AL-W strain was tolerant to lambda-cyhalothrin (RR50 = 4.09). PBO reduced RR50 to 0.18 and increased the toxicity by 22.5-folds (LC50 = 0.002 ppm). PBO suppressed the resistance to both beta-cyfluthrin and lambda-cyhalothrin by 96%. LC50 values of bifenthrin decreased, compared to those of 24 h post treatment, that were 0.0039 and 0.225 ppm for S-LAB and AL-W strains respectively. In contrast, the resistance of AL-W strain increased to bifenthrin (RR50 = 57.7). Remarkable increase in bifenthrin toxicity was observed (LC50 = 0.0003 ppm) as a result of PBO addition (SR50 = 750) and a dramatic resistance suppression (99.87%) was observed.

Table 3.

Toxicity of some pyrethroid insecticides to Cx. pipiens after 48 h of exposure.

| Insecticide | Strain | LC50 ppm (95% CL) | LC95 ppm (95% CL) | Slope ± SE | RR50 | SR50 | RS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-cyfluthrin | S-LAB | 0.0028 (0.0019–0.004) | 0.954 (0.304–6.454) | 0.651 ± 0.086 | |||

| AL-W | 0.069 (0.054–0.09) | 0.252 (0.204–0.428) | 2.918 ± 0.193 | 24.6 | |||

| Beta-cyfluthrin + PBO | AL-W | 0.0028 (0.0019–0.004) | 0.955 (0.304–6.471) | 0.651 ± 0.086 | 1 | 24.6 | 96 |

| Lambda-cyhalothrin | S-LAB | 0.0011 (0.0009–0.0013) | 0.016 (0.011–0.026) | 1.432 ± 0.125 | |||

| AL-W | 0.0045 (0.0038–0.0052) | 0.03 (0.022–0.05) | 1.983 ± 0.218 | 4.09 | |||

| Lambda-cyhalothrin + PBO | AL-W | 0.0002 (0.0002–0.0002) | 0.0011 (0.0008–0.0017) | 2.290 ± 0.248 | 0.18 | 22.5 | 96 |

| Bifenthrin | S-LAB | 0.0039 (0.0016–0.0081) | 0.044 (0.044–0.501) | 1.567 ± 0.129 | |||

| AL-W | 0.225 (0.19–0.269) | 1.195 (0.855–1.886) | 2.258 ± 0.193 | 57.7 | |||

| Bifenthrin + PBO | AL-W | 0.0003 (0.0000048–0.0026) | 0.236 (0.12–2.013) | 0.572 ± 0.18 | 0.08 | 750 | 99.87 |

RR50, resistance ratio at LC50 (RR50 = LC50 of field population/LC50 of S-LAB); SR50, synergism ratio (SR50 = LC50 in absence of PBO/LC50 in presence of PBO); RS (%), resistance suppression % (RS (%) = [1 − (LC50 in presence of PBO/LC50 in absence of PBO)] * 100).

Data in Table 4 shows the toxicity of fenitrothion against S-LAB and WN1 populations as well as the inhibitory effect on AChE activity. The LC50 values of fenitrothion against Cx. pipiens S-LAB and WN1 populations were 0.116 and 0.198 ppm, respectively, and the RR50 was 1.7. The determined I50 values were very close (0.078 and 0.073 ppm for S-LAB and WN1 respectively).

Table 4.

Toxicity of fenitrothion to Cx. pipiens and its inhibition effect on AChE activity.

| Insecticide | Strain | LC50 ppm (95%CL) | Slope ± SE | RR50 | I50 ppm (95%CL) | Slope ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fenitrothion | S-LAB | 0.116 (0.101–0.131) | 2.62 ± 0.04 | 0.078 (0.053–0.113) | 1.16 ± 0.024 | |

| WN1 | 0.198 (0.175–0.224) | 2.32 ± 0.037 | 1.7 | 0.073 (0.05–0.09) | 1.43 ± 0.027 |

RR50, resistance ratio at LC50 (RR = LC50 of field population/LC50 of S-LAB).

4. Discussion

The present study revealed low resistance levels of Cx. pipiens WN1 and WN2 populations to fenvalerate and high resistance levels (187.1- and 161.4-folds) to deltamethrin. Four years earlier, resistance ratios of 10- and 8.5-folds of Cx. pipiens populations from Irqa and EL-Nafl localities in Riyadh city, were recorded to deltamethrin (Al-Sarar et al., 2005). In agreement with the present results, high resistance levels of Cx. pipiens pipiens (233 and 453 fold) to deltamethrin were reported in Tunisia (Daaboub et al., 2008). The field population AL-W displayed low level of resistance to lambda-cyhalothrin and moderate levels to beta-cyfluthrin and bifenthrin. Low resistance level was also reported in Cx. quinqefasciatus field strain from Brazil (González et al., 1999) and Malaysia (Nazni et al., 2005) against lambda-cyhalothrin. The AL-W population was susceptible to fenitrothion. This might be contributed to that the municipality of Riyadh does not use this compound regularly. The I50 values of AChE, the target site of fenitrothion, revealed that susceptibilities of S-LAB and WN1 populations were very close. In Sri Lanka, AChE was also found to be sensitive to organophosphate insecticides in Kurunegala and Trincomalee An. culicifacies field populations (Perera et al., 2008).

PBO is a pesticide synergist and acts as a potent inhibitor to cytochrome P450 and non-specific esterase (Moores et al., 2009). The present data showed a dramatic suppression of resistance (>90%) when PBO was combined with all tested Pyrethroid insecticides, suggesting that P450 monooxygenase- and non-specific esterase-mediated detoxification contributes to pyrethroids resistance in WN1, WN2 and AL-W field populations. McAbee et al. (2003) reported that pyrethroid resistance developed in Cx. pipiens from California, was almost completely suppressed by PBO, suggesting the involvement of cytochrome P450- and carboxylesterase-mediated detoxification in resistance. Using the same synergist, Penilla et al. (2007) demonstrated that monooxygenases were responsible for nearly 80% of deltamethrin resistance in Anopheles albimanus. Moores et al. (2009) demonstrated that PBO not only inhibits microsomal oxidases but also resistance-associated esterases. The ability to inhibit both major metabolic resistance enzymes makes PBO an ideal synergist to enhance insecticides.

In summary, the present results indicate that PBO is an effective synergist to pyrethroid insecticides and it enhances their toxicity against Cx. pipiens resistant populations. Mixing PBO with pyrethroids minimizes the amount of applied insecticides and leads to economic and environmental benefits. The results of the present study should be considered in the current control programs to combat mosquitoes in Saudi Arabia.

References

- Abbott W.S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 1925;18:265–267. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah M.A., Merdan A.I. Distribution and ecology of the mosquito fauna in the southwestern Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 1995;25(3):815–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alahmed A.M., Kheir S.M. Seasonal activity of some haematophagous insects in the Riyadh Region, Saudi Arabia. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2005;4(2):95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Alahmed A.M., El-Khereji M.A., Kheir S.M. Distribution and habitats of mosquito larvae (Diptera: Culicidae) in Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia. J. King Saud Univ. Agric. Sci. 2007;19(2):39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghamdi K., Alikhan M., Mahyoub J., Afifi Z.I. Studies on identification and population dynamics of anopheline mosquitoes from Jeddah province of Saudi Arabia. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Commun. 2008;1:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sarar A.S., Hussein H.I., Al-Rajhi D., Al-Mohaimeed S. Susceptibility of Cx. pipiens from different locations in Riyadh city to insecticides used to control mosquitoes in Saudi Arabia. J. Pest Cont. Environ. Sci. 2005;13:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ayyub M., Khazendar A.M., Lubbad E.H., Barlas S., Alfi A.Y., Al-Ukayli S. Characteristics of dengue fever in a large public hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2006;18(2):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman J.G. The ears of the hippopotamus: manifestation, determinants and estimates of the malaria burden. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2001;64:1–11. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissat J., Rodrigues M., Soca A., Pasteur N., Raymond M. Cross-resistance to pyrethroid and organophosphorous insecticides in the southern house mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) from Cuba. J. Med. Entomol. 1997;34(2):244–246. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttiker W. Fauna of Saudi Arabia: observations on urban mosquitoes in Saudi Arabia. Fauna Saudi Arabia. 1981;3:472–479. [Google Scholar]

- CDC Provisional surveillance summary of the West Nile Virus epidemic – US, Morb. Mort. Weekly Rep. 2002;51:1129–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui F., Lin L.F., Qiao C.L., Xu U., Marquine M., Weill M., Raymond M. Insecticide resistance in Chinese populations of the Cx. pipiens complex through esterase overproduction. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2006;120:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Daaboub J., Ben Cheikh R., Lamari A., Ben J.I., Feriani M., Boubaker C., Ben Cheikh H. Resistance to pyrethroid insecticides in Cx. pipiens pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) from Tunisia. Acta Trop. 2008;107:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge B.F., Scott T.W., Day J.F., Tabachnick W.J. Arbovirus diseases. In: Eldridge B.F., Edman J.D., editors. Medical Entomology, a Textbook on Public Health and Veterinary Problems Caused by Arthropods. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht: 2000. pp. 415–460. [Google Scholar]

- El-Khereji, M.A., 2005. Survey and Distribution of Mosquito species (Diptera: Culicidae) and Description of Its Habitat in Riyadh District, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. M.Sc. Thesis King Saud University. College of Food and Agricultural Science, 120pp.

- El-Khereji M.A., Alahmed A.M., Kheir S.M. Survey and seasonal activity of adult mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Food Sci. Agric. Res. Centre Res. Bull. 2007;152:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ellman G.L., Courtney K.D., Andres V., Jr., Featherstone R.M. A new rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharm. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney D.N. third ed. Cambridge Univ. Press; London: 1971. Probit Analysis. pp. 318. [Google Scholar]

- González T., Bisset J.A., Díaz C., Rodríguez M.M., Brandolini M.B. Insecticide resistance in a C. quinquefasciatus strain from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro. 1999;94(1):121–122. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000100023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardstone M.C., Baker S.A., Ewer J., Scott J.G. Deletion of Cyp6d4 does not alter toxicity of insecticides to Drosophila melanogaster. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2006;84:236–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hemingway J., Callaghan A., Amin A.M. Mechanisms of organophosphate and carbamate resistance in C. quinquefasciatus from Saudi Arabia. Med. Veter. Entomol. 1990;41:275–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1990.tb00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupp P.G., Kemp A., Grobbelaar A., Leman P., Burt F.J., Al Ahmed A.M., Almujalli D., Alkhamees M., Swanepoel R. The 2000 epidemic of Rift Valley fever in Saudi Arabia: mosquito vector study. Med. Veter. Entomol. 2002;16:245–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2002.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai S., Komagata O., Tomita T., Sawabe K., Tsuda Y., Kurahashi H., Ishikawa T., Motoki M., Takahashi T., Tanikawa T., Yoshida M., Shinjo G., Hashimoto T., Higa Y., Kobayashi M. PCR-based identification of Cx. pipiens complex collected in Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;61:184–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry O.H., Rosebrough N.J., Farr A.L., Randall R.J. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAbee R.D., Kang K.D., Stanich M.A., Christiansen J.A., Wheelock C.E., Inman A.D., Hammock B.D., Cornel A.J. Pyrethroid resistance in Cx. pipiens var molestus from Marin Country. Calif. Pest Manag. Sci. 2003;60:359–368. doi: 10.1002/ps.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moores G.D., Philippou D., Borzatta V., Trincia P., Jewess P., Gunning R., Bingham G. An analogue of piperonyl butoxide facilitates the characterisation of metabolic resistance. Pest Manag. Sci. 2009;65:150–154. doi: 10.1002/ps.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazni W.A., Lee H.L., Azahari A.H. Adult and larval insecticide susceptibility status of C. quinquefasciatus (Say) mosquitoes in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. Trop. Biomed. 2005;22:63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omer M.S. A survey of bancroftian filariasis among South-East Asian expatriate workers in Saudi Arabia. Trop. Med. Inter. Health. 1996;1:155–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.1996.tb00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris H.T.R., Hemingway J. Mechanism of insecticide resistance in a temephos selected C. quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) strain from Sri Lanka. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1990;80(4):453–457. [Google Scholar]

- Penilla R.P., Rodríguez A.D., Hemingway J., Terjo A., López A.D., Rodríguez M.H. Cytochrome P450-based resistance mechanism and pyrethroid resistance in the field Anopheles albimanus resistance management trial. Pesic. Biochem. Physiol. 2007;89:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Perera M.D.B., Hemingway J., Karunaratne S.H.P. Multiple insecticide resistance mechanisms involving metabolic changes and insensitive target sites selected in anopheline vectors of malaria in Sri Lanka. Malaria J. 2008;7:168–178. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A., Kumar S., Pillai M.K.K. Piperonyl butoxide as a counter measure for deltamethrin-resistance in C. quinquefasciatus. Say. Entomon. 1991;18:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Turell M.J., O’Guinn M.L., Dohm D.J., Jones J.W. Vector competence of North American mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidar) for West Nile Virus. J. Med. Entomol. 2001;38:130–134. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingradova E.B. Pensoft Publishers; Sofia, Bulgaria: 2000. Cx. pipiens pipiens Mosquitoes: Taxonomy, Distribution, Ecology, Physiology, Genetics, Applied Importance and Control. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 1976. 22nd Report by the Expert Committee on Insecticides, p. 77.

- Xu Q., Liu H., Zhang L., Liu N. Resistance in the mosquito, C. quinquefasciatus, and possible mechanisms for resistance. Pest Manag. Sci. 2005;61:1096–1102. doi: 10.1002/ps.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]