Abstract

The plasma protein properdin is the only known positive regulator of complement activation. Although regarded as an initiator of the alternative pathway of complement activation at the time of its discovery more than a half century ago, the role and mechanism of action of properdin in the complement cascade has undergone significant conceptual evolution since then. Despite the long history of research on properdin, however, new insight and unexpected findings on the role of properdin in complement activation, pathogen infection and host tissue injury are still being revealed by ongoing investigations. In this article, we provide a brief review on recent studies that shed new light on properdin biology, focusing on the following three topics: 1) its role as a pattern recognition molecule to direct and trigger complement activation, 2) its context-dependent requirement in complement activation on foreign and host cell surfaces, and 3) its involvement in alternative pathway complement-mediated immune disorders and considerations of properdin as a potential therapeutic target in human diseases.

Introduction

Properdin (P) is a plasma glycoprotein of the complement system. It is the only known positive regulator of the complement cascade, with a history of discovery dating back to when the precise activation pathways of the complement system were still being elucidated (Lachmann, 2009; Maves and Weiler, 1993; Pillemer et al., 1954). Complement is a crucial branch of the innate immune system responsible for the recognition and removal of pathogens and cellular debris from the host organism. Over 30 proteins in circulation and on the cell surface work together in a delicate balance to drive complement activation on pathogens and cellular debris while protecting the host tissue from bystander injury. Complement activation is triggered by three main pathways-classical, lectin and alternative. While the classical and lectin pathways are initiated in response to recognition of specific markers on pathogens and susceptible surfaces (antigen-antibody complexes and pathogen-associated carbohydrates, respectively), the alternative pathway (AP) is constitutively active at a low level in circulation (Dunkelberger and Song, 2010; Lachmann, 2009). This phenomenon, referred to as the tick-over mechanism, is triggered by spontaneous hydrolysis of C3 to C3 (H2O) which, like the activated C3 fragment C3b, can bind to factor B (fB) and allow factor D to cleave fB (Lachmann, 2009; Pangburn and Muller-Eberhard, 1983). This enzymatic complex C3 (H2O) Bb acts as a C3 convertase to cleave C3 into C3a and C3b to opsonize targets and propagate further complement activation through the formal AP C3 convertase C3bBb (Lachmann, 2009). Newly formed C3bBb complex is rather labile and undergoes rapid spontaneous decay (Medicus et al., 1976a; Pangburn and Muller-Eberhard, 1986). However, it is stabilized by P. Binding of P increases the half-life of C3bBb five to ten-fold (Fearon and Austen, 1975). On the other hand, several fluid phase and membrane-bound complement regulators, including factor H (fH) and decay-accelerating factor (DAF), work to promote the decay and inactivation of C3bBb and thus help protect host cells from complement injury (Dunkelberger and Song, 2010; Liszewski et al., 1996).

While this mechanism of spontaneous complement activation and turnover- via the AP and involving opposing actions of P and the negative regulators on C3bBb- has been well established over the years, recently renewed interest in P has stimulated a re-examination of its mode of action and highlighted several unresolved questions regarding its biology. Among them, the concept of P acting as a pattern recognition molecule to direct and trigger AP complement activation in addition to its well established role in stabilizing the AP C3 convertase C3bBb has gained new attention. In vitro and in vivo complement assays have also shown that P is indispensible under some but not all settings of AP complement activation. It even appears to contribute, in some cases critically, to the classical and lectin pathways of complement activation. Additionally, while several studies in mice implicated P in the pathogenesis of complement-mediated tissue injury and demonstrated a beneficial effect of its inhibition, recent experiments in mouse models of C3 glomerulopathy have revealed an unexpected protective effect of P. Thus, complete understanding of the role of P in complement activation and disease pathogenesis remains a goal to be achieved.

Properdin as a pattern recognition molecule to direct AP complement activation?

While the role of P as a stabilizer of the AP C3 convertase C3bBb is well established, the hypothesis that P may also work as a pattern recognition molecule to direct and trigger AP complement activation has recently gained new consideration, largely stimulated by the insightful biochemical studies of Hourcade and colleagues (Hourcade, 2006; Spitzer et al., 2007). The concept that P initiates AP complement activation harks back to the discovery of the AP itself, which was once referred to as the “properdin pathway” (Pillemer et al., 1954). However, while the existence of AP was subsequently established and the “tick-over” mechanism of activation became universally accepted, the concept of P functioning as an initiator of the pathway fell to the wayside, being replaced by the now well known activity of P as a stabilizer of preformed C3bBb (Maves and Weiler, 1993). By conjugating purified P to Biacore sensor chips, Hourcade demonstrated that P could help assemble C3bBb complexesde novo on a surface (Hourcade, 2006). These experiments thus unequivocally showed that surface-bound P can indeed initiate AP complement activation by providing a platform for new C3bBb formation. The investigators further demonstrated that purified P was able to bind to a variety of AP complement-susceptible particle and cell surfaces, including zymosan, rabbit erythrocytes and Neisseria gonorrhoeae(Spitzer et al., 2007). Significantly, P-opsonized zymosan, bacteria and erythrocytes activated AP complement in the absence of additional serum P (Spitzer et al., 2007). Subsequent studies by the same group and others extended these initial observations, demonstrating that P was also able to bind to early apoptotic T cells (Kemper et al., 2008), late apoptotic and necrotic T cells (Xu et al., 2008), plate-immobilized LPS and LOS (Kimura et al., 2008), E. coli of the DH5α strain (Stover et al., 2008) and kidney proximal tubule epithelial cells (Gaarkeuken et al., 2008). In further studies, the P-binding ligand on several types of target cells was identified as glycosaminoglycans such as heparan sulfate proteoglycan (Kemper et al., 2008; Zaferani et al., 2011).

Despite these suggestive observations, however, one problem in envisioning P as a pattern recognition molecule to direct and trigger AP complement activation on specific surfaces was the inability to demonstrate direct binding of serum P in the absence of C3 (Kimura et al., 2008; Spitzer et al., 2007). Indeed, while purified human P bound to zymosan, P from C3-depleted human serum failed to do so (Spitzer et al., 2007). Likewise, in a functional assay, plate-bound LPS activated AP complement in P knockout (P−/−) mouse serum after incubating with purified P but not after incubation with C3-depleted human or C3 knockout (C3−/−) mouse serum (as a source of P) (Kimura et al., 2008). Other studies detected P binding on E. coli and zymosan after incubation with human serum but binding was abolished in the presence of EDTA or the complement inhibitor Compstatin (Harboe et al., 2012; Stover et al., 2008). The only published study of C3-independent P binding to susceptible cells is a report in which serum P from normal or C3-deficient serum was found to bind similarly to necrotic cells, although the binding was relatively weak (Xu et al., 2008). Thus, existing evidence overwhelmingly supports the conclusion that serum P does not bind to AP activators in the absence of surface-bound C3b.

The above findings led to the hypothesis that some serum factors may compete or inhibit P binding to cell surfaces, perhaps as a protective mechanism to prevent constitutive AP complement activation (Kemper et al., 2010; Kemper et al., 2008). Given that properdin is largely made and released from leukocytes, the idea was tested that freshly secreted properdin in the local microenvironment may escape sequestration of serum inhibitory factors and be able to bind and opsonize target cells. In one study, it was shown that while P from C3-depleted human serum failed to bind to early apoptotic T cells, both purified P and freshly released P from activated neutrophils were able to bind to these cells (Kemper et al., 2008). This mechanism, however, may not operate in other settings of AP complement activation, as other investigators found freshly released P from activated neutrophils to be incapable of binding to zymosan or E. coli(Harboe et al., 2012). It is interesting that P opsonization of apoptotic T cells facilitated their phagocytosis through a complement-independent mechanism, raising the possibility that recognition and binding of certain target cells by neutrophil-derived P represents a physiological function of P unrelated to AP complement activation (Kemper et al., 2008).

The biological relevance of binding of purified P to the tested AP complement activators was also called into question by the demonstration of Ferreira and colleagues who showed that polymeric forms of properdin- artifactsin purified properdinon prolonged storage- may have accounted for much of the observed binding (Ferreira et al., 2010). Under physiological conditions, P exists in the plasma as cyclic dimers, trimers and tetramers (P2, P3 and P4) in a fixed ratio (Pangburn, 1989). Repeated freezing and thawing of purified P during storage may cause the oligomeric P to aggregate and form polymers of undefined sizes (Pn) (Farries et al., 1987; Pangburn, 1989). Historically, Pnwas referred to as “activated P” because unlike the native P2-P4 it caused AP complement activation and C3 consumption when added to normal serum (Farries et al., 1987). Using freshly separated P, it was demonstrated that P2-P4 could bind specifically to zymosan, necrotic Raji and Jurkat cells and Chlamydia pneumoniae, but not to rabbit erythrocytes or live cells (Cortes et al., 2011; Ferreira et al., 2010). In contrast, Pnor unfractionated P bound to almost all AP activating cells or surfaces tested (Ferreira et al., 2010). Notably, even though purified native P2-P4 was able to bind Chlamydia pneumonia, no P binding could be detected using human serum in the presence of EDTA (Cortes et al., 2011). Similarly, Agarwal et al found that while serum P played a critical role in AP complement activation and killing of diverse strains of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, purified native P2-P4did not bind to any of the strains. However, unfractionated P and purified Pn did bind to these bacteria (Agarwal et al., 2010).

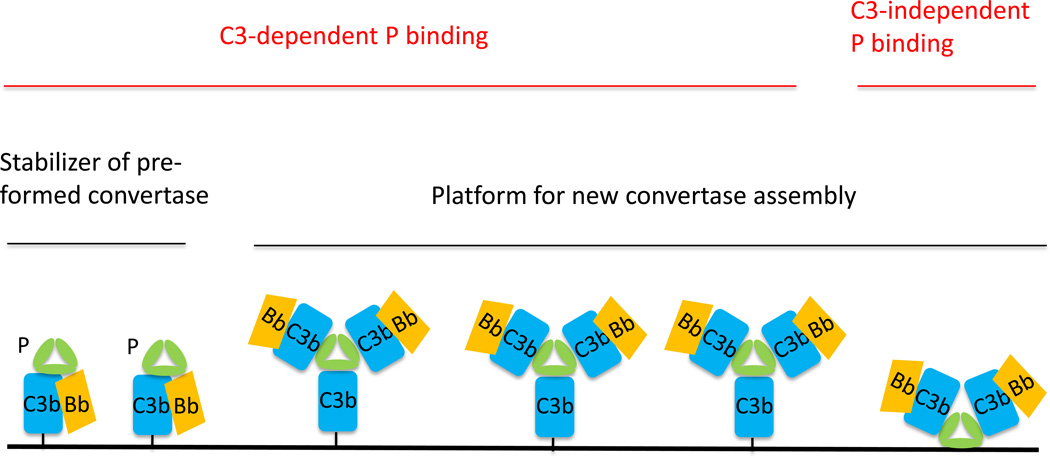

Taken together all available evidence, it seems clear that in most settings P does not work independently of C3 as a pattern recognition molecule to direct and initiate AP complement activation. Thus, for a given target cell or pathogen, susceptibility to AP complement attack is unlikely to be determined by its affinity for C3-independent P binding. It should be pointed out that even if serum P initially binds to a target surface in a C3-independent manner, subsequent de novo assembly of C3bBb would still require the tick-over mechanism to provide C3b molecules as P itself, whether in solution or surface bound, does not possess protease activity. Therefore, the question of whether P can bind target cells independently of C3 or not is perhaps of little relevance to complement activation under typical conditions in vivo, because the presence of P and C3 tick-over in plasma and other biological fluids means that iterative interaction between P and C3b on target cells is a default outcome. How should these findings and considerations shape our understanding of P function in AP complement activation? We envision that for most target cells the C3 tick-over mechanism provides the initial surface ligand (C3b) for P binding. In some settings, cell surface glycosaminoglycans may also serve as P liagnds (Kemper et al., 2008; Zaferani et al., 2011). Once surface-bound, the oligomeric P can then serve as a platform for de novo C3bBb convertase assembly (Figure 1). This mechanism is presumably more efficient in capturing solution C3b than relying on tick-over generated C3b to randomly cross-link to surface NH2 or hydroxyl groups via covalent bonding. Thus, the role of P in AP complement activation can be viewed as twofold, stabilizing preformed C3bBb (covalently bonded to the surface) and assembling new C3bBb (non-covalently bonded, attached to P). Importantly, both functions of P are dependent on the C3 tick-over mechanism (Figure 1).

Fig 1. Model of P function on the cell surface.

P promotes AP complement activation on the cell surface by two mechanisms, as a stabilizer of pre-formed C3 convertase C3bBb and as a platform to recruit solution C3b and assemble new C3bBb convertase. Both mechanisms require fluid phase C3 tick over to provide C3b molecules. Binding of P to AP activators is primarily through surface-deposited C3b, but under some circumstances (e.g. in local tissue microenvironment) P may also bind to cells directly using glycosaminoglycans as ligands.

Context-dependent requirement of properdin in complement activation

Apart from the mechanism of action of P as discussed above, another intriguing question related to P function is why it is indispensible in some settings of AP complement activation but not others. Indeed, P-deficient individuals can be identified by the LPS-based ELISA AP assay but not by the traditional AP-based hemolytic assay (Kimura et al., 2008), suggesting that P is required in the former but not the latter AP assay. Clinically, it is observed that P deficiency confers a special risk of Neisseria meningitides infection, but the mechanism of this selective pathogen susceptibility is not well understood (Fijen et al., 1999). One interpretation is that the clearance of meningitides bacteria is principally mediated by P-dependent AP complement, whereas there are redundant complement activation pathways and/or innate immune effectors in the elimination of other bacterial and viral pathogens. In an experiment conducted with the mouse complement system, lipooligosaccharide (LOS), an outer membrane component of meningitides bacteria, was found to be a poor activator of the classical and lectin pathways of complement, whereas lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from other common Gram-negative bacteria activated complement efficiently through both P-dependent and -independent pathways (Kimura et al., 2008).

The activator-specific requirement of P in AP complement activation was first clearly demonstrated experimentally using P−/− mouse serum. Given the known role of P as a stabilizer of C3bBb, it was surprising to find that P deficiency in the mouse serum completely abrogated LPS-induced AP complement activation (Kimura et al., 2008), even when high serum concentration (e.g. 50%) was used for the assay (Y. Kimura and W.-C. Song, unpublished data). Equally unexpected was the contrasting observation that P deficiency only minimally impaired zymosan-induced AP complement activation in the mouse serum (Kimura et al., 2008). However, the latter result was in discordance with studies of the human complement system where P was found to be essential for zymosan to activate the AP (Agarwal et al., 2011; Ferreira et al., 2010; Spitzer et al., 2007). Thus, whether P plays a critical role in AP complement activation depends on the nature of the activator and varies with the species of origin of the complement being studied. The reason for the differential requirement of P in these settings is unknown, but as discussed above, it is unlikely to be related to the affinity of C3-indepenent P binding. It is possible that the degree of interaction with negative regulators such as fH and factor I (fI) by an activating surface determines its reliance on P. This would agree with the finding that P appears to be invariably required for AP complement activation on autologous cells where multiple negative regulatory mechanisms exist (Dimitrova et al., 2012; Dimitrova et al., 2010; Kimura et al., 2008; Kimura et al., 2010; Lesher et al., 2013; Miwa et al., 2012; Zaferani et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2012). Thus, a P-dependent AP complement activator such as LPS may have a better interaction with mouse fH/fI than a P-independent mouse AP complement activator such as zymosan.

Because AP is usually activated and plays a key role in amplifying the CP and LP, the issue of whether P is required for full CP and LP activation has also received attention and study. The answer to this question, however, is not straightforward and may depend on what assays or readouts are used to assess CP and LP activation. Serum dilution factors may also affect experimental results as AP activity is more sensitive than CP activity to serum dilution. Some in vitrostudies with anti-P antibodies and heparin-protamine or immune complexes and mannan have indicated a significant role of P in the AP amplification loop of CP and LP of human complement (Gupta-Bansal et al., 2000; Harboe et al., 2009). In these experiments, CP and LP complement activation was monitored by measuring fluid phase C3a and terminal complement complex (TCC) levels, as well as solid phase TCC deposition (Gupta-Bansal et al., 2000; Harboe et al., 2009). Interestingly, blocking P binding caused a significant reduction in fluid phase C3a or TCC release but only had a minor effect on solid phase TCC deposition (Gupta-Bansal et al., 2000; Harboe et al., 2009). In a separate study, the effect of P deficiency on immune complex-mediated CP activation was assessed by ELISA using WT, fB−/− and P−/− mouse serum with solid phase C3 deposition as the primary readout (Kimura et al., 2008). This experiment showed that while fB deficiency significantly reduced C3 deposition, suggesting the existence of an AP amplification loop, P deficiency did not affect C3 deposition on the ELISA plate (Kimura et al., 2008). Lack of an effect of P inhibition on CP and LP complement activation has also been reported by others recently in an experiment with human complement (Heinen et al., 2013). Thus, available data from in vitro experiments on this topic are mixed.

A fascinating example of context-specific requirement of P in CP complement-mediated bacterial killing is provided by the study of Gulati et al (Gulati et al., 2012). Previous work demonstrated that N. gonorrhoeae could be killed by complement attack, primarily by the CP, but resistance is emerging as strains acquire various mechanisms to avoid complement attack, such as the ability to recruit fH and C4 binding protein (C4bp) (Ingwer et al., 1978; Ram et al., 2001; Ram et al., 1998). A potent antibody (2C7) against gonococcal LOS has previously been developed and characterized as a potential vaccine (Yamasaki et al., 1999) but its effectiveness for inducing complement activation varied among different strains (Gulati et al., 2012). While CP activation was known to be critical for bactericidal activity in all strains, inhibition of the AP with an anti-fB mAb significantly diminished complement killing in a number of strains (Gulati et al., 2012). Inhibition of P activity with an anti-P mAb produced similar results to those seen with the anti-fB mAb. Interestingly, Gulati and colleagues found that strains which were sensitive to AP attack also had significant C4bp binding, suggesting that AP activation, and in particular P, was important for complement attack when CP activity was inhibited (i.e. by recruiting C4bp) (Gulati et al., 2012). Importantly, the requirement of P and AP amplification extended beyond the 2C7 mAb and was found to be true under more general conditions with serum from a mouse immunized with a gonococcal bacterial membrane preparation that did not react strongly with LOS (Gulati et al., 2012). Thus, P was not required for CP complement-mediated killing of gonococcal bacteria unless the initiating activity of CP was attenuated by C4bp. This study has demonstrated that the role of P in AP complement amplification is context specific and depends on the strength of the initial complement activation trigger, whether the trigger is provided by the C3 tick-over mechanism or by the CP or LP pathway.

Role of properdin in complement-mediated tissue injury

Given the above considerations and the fact that host cells are naturally resistant to complement activation, it is perhaps not surprising that P has been invariably found to be critical for AP complement activation on autologous cells. A number of complement-dependent autoimmune disorders are now recognized to be primarily mediated by the AP (Holers, 2008), however, the relevance of P in these disease settings was not addressed until relatively recently. Indeed, apart from increased risk of N. meningitides infection in P-deficient individuals, our knowledge on the role of P in human health and disease had been essentially blank. The first indication that P may play a critical role in AP complement-mediated tissue injury, and thus may represent a promising therapeutic target, came from the study of P−/− mice in an extravascular hemolysis disease model (Kimura et al., 2008). The membrane-bound protein Crry is a critical AP complement regulator in mice and its deficiency caused embryonic lethality (Xu et al., 2000). Deficiency of Crry from the mouse erythrocytes also rendered them susceptible to AP complement-mediated extravascular hemolysis (Miwa et al., 2002). Using an erythrocyte transfusion protocol, it was demonstrated that P played a critical role in this process (Kimura et al., 2008). Crry-deficient mouse erythrocytes were rapidly eliminated when transfused into WT mice but such cells survived when transfused into P−/− mice (Kimura et al., 2008). Subsequently, it was also shown that P deficiency, like fB deficiency, was able to rescue Crry-deficient mice from embryonic lethality (Kimura et al., 2010). Thus, in the Crry knockout mouse model, P played a critical role in enabling AP complement-mediated attack of developing fetuses and mature red blood cells (Kimura et al., 2008; Kimura et al., 2010).

Studies from several laboratories have established a role of P in other settings of AP complement-mediated tissue injury. In both the adoptive K/BxN mouse serum transfer and zymosan-induced models of arthritis, P deficiency was shown to be protective (Dimitrova et al., 2010; Kimura et al., 2010). Furthermore, blocking P function by a neutralizing antibody ameliorated arthritis development in the K/BxN model (Kimura et al., 2010). Conversely, reconstitution of P, mice with exogenous P restored sensitivity to arthritis induction by the pathogenic K/BxN mouse serum (Kimura et al., 2010). The latter experiment provided important mechanistic insight in that it showed systemic rather than locally released P contributed to tissue injury in the joint. Thus, targeting systemic P therapeutically in AP complement-mediated diseases may be effective and feasible. A critical role of P in elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), another murine model of AP complement-mediated pathology has also been established recently (Zhou et al., 2012). In this model, IgG autoantibodies against natural antigens exposed on injured aorta are thought to trigger AP complement activation, which is facilitated by P. Like the arthritis model, AAA was ameliorated in P-deficient mice and in WT mice treated by an anti-P antibody (Zhou et al., 2012). Most recently, a role of P in renal ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) was demonstratedin a mouse model (Miwa et al., 2012). Brief bilateral pedicle clamping followed by 24 hrs reperfusion in DAF−/−/CD59−/− mice caused severe AP complement-dependent tubular injury (Miwa et al., 2012). Compared with WT mice, P−/− mice incurred significantly reduced injury and blocking P with systemic administration of a mAb before IR surgery had a similar ameliorating effect (Miwa et al., 2012).

There is indirect evidence that P may be implicated in the pathogenesis of human anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-mediated glomerulonephritis. A recent clinical study found increased plasma levels of activated complement products (C3a, C5a, C5b-9 and Bb) but decreased P levels in ANCA patients with active disease, suggesting P may be consumed during complement activation in disease flares (Gou et al., 2013). Earlier studies in a murine model of ANCA induced by anti-MPO antibodies have established the requirement of AP complement (Xiao et al., 2007). It was postulated that binding of ANCA to their cognate antigens on the surface of neutrophils causes them to degranulate and release P to trigger and amplify AP complement activation in the kidney, resulting in glomerular injury (Xiao et al., 2007). This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that neutrophils are a rich source of P production (Schwaeble and Reid, 1999; Wirthmueller et al., 1997)-in a recent study, tissue-specific deletion of the P gene from myeloid lineage cells in Pflox/flox-lysozyme-Cre mice resulted in more than 95% reduction of plasma P (Miwa et al., 2012). It is also supported by the observation of Camous et al who found that P released from neutrophils could bind to activated neutrophils to initiate AP activation on the cell surface and promote additional neutrophil activation in a potential positive feedback loop (Camous et al., 2011). Whether P contributes to the pathogenesis of ANCA glomerulonephritis and can be targeted therapeutically in this disease remains to be tested experimentally.

While the studies described above pointed to a detrimental role of P in AP complement-mediated tissue injury, a pair of recent studies in murine models of C3 glomerulopathy surprisingly revealed a protective role of P and suggested that therapeutic targeting of P may not always be desirable (Daha, 2013; Lesher et al., 2013; Ruseva et al., 2013). The fluid phase complement regulator fH plays a key role in preventing AP complement activation in the fluid phase and on the cell surface (Pangburn, 2000; Thompson and Winterborn, 1981). As a plasma protein, fH exerts its regulatory function on the cell surface by preferentially interacting with host cell-specific constituents such as glycosaminoglycans, as well as surface deposited C3b/C3d, through its C-terminal domain, mainly short consensus repeat (SCR) 19 and 20 (Schmidt et al., 2008). Mutations in fH that lead to impaired cell surface binding have been associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), whereas mutations that impair its complement-regulating activity or reduce its expression level are more commonly found in C3 glomerulopathy patients (de Cordoba and de Jorge, 2008; Fakhouri et al., 2010). Two forms of C3 glomerulopathy, dense deposit disease (DDD, previously called membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis [MPGN] type II) and C3 glomerulonephritis (C3 GN), fall within this recent pathological classification. Both are characterized by uncontrolled plasma AP complement activation with C3, fB and in some cases C5 consumption, and glomerular C3 deposition in the absence of significant IgG staining (Fakhouri et al., 2010; Sethi et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012). C3 glomerulopathy can also be caused by mutations in C3 and fB genes that result in aberrant C3 convertases resistant to regulation by fH/fI and membrane complement inhibitors (Martinez-Barricarte et al., 2010; Strobel et al., 2010) or by C3 nephritic factors (C3NeF)- IgG antibodies that bind and stabilize the AP C3 convertase complex C3bBb or C3bBbP (Fakhouri et al., 2010; Servais et al., 2007; Servais et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2011). Historically, some C3NeFs are known to cause both C3 and C5 consumption and their activity is dependent on P (P-dependent C3NeF), while other C3NeFs are independent of P and cause only C3 consumption (P-independent C3NeF) (Clardy et al., 1989; Mollnes et al., 1986; Tanuma et al., 1990; Varade et al., 1990). P-dependent C3 NeFs are usually found in MPGN type I and III patients (C3 GN in the new classification), whereas P-independent C3NeFs are more frequently associated with MPGN type II (or DDD), the clinically more severe form of C3 glomerulopathy (Clardy et al., 1989; Varade et al., 1990).

Mice genetically engineered to be totally deficient in fH (fH−/−) or carry a C-terminal truncation mutation leading to markedly reduced fH expression (fHm/m) were found to have uncontrolled plasma AP complement activation and extensive C3/C5 consumption (Lesher et al., 2013; Pickering et al., 2002; Ruseva et al., 2013). These mice developed C3 glomerulopathy with characteristic C3 deposition in the glomeruli (Lesher et al., 2013; Pickering et al., 2002; Ruseva et al., 2013). In studies aimed at determining the role of P in C3 glomerulopathy caused by fH deficiency or insufficiency, two groups independently found that P deficiency, either by gene deletion or antibody blocking, unexpectedly exacerbated the kidney disease (Lesher et al., 2013; Ruseva et al., 2013). Inhibiting P had an especially striking effect in fHm/m mice. While fHm/m mice developed a relatively mild and slow-progressing C3 GN with mortality being observed only by 8–10 month of age, fHm/m/P−/− mice or fHm/m mice treated with an anti-P antibody developed high proteinuria by as early as 6–8 weeks of age and the majority died from crescentic GN before reaching 3 month old (Lesher et al., 2013). Likewise, significantly worsened pathology and more abundant C3 deposition were observed in fH−/−/P−/− mouse kidneys than in fH−/− mouse kidneys (Ruseva et al., 2013). Given the previously demonstrated detrimental role of P in other models of AP complement-mediated injury, these results showing an apparently protective role of P in C3 GN were rather surprising and counterintuitive.

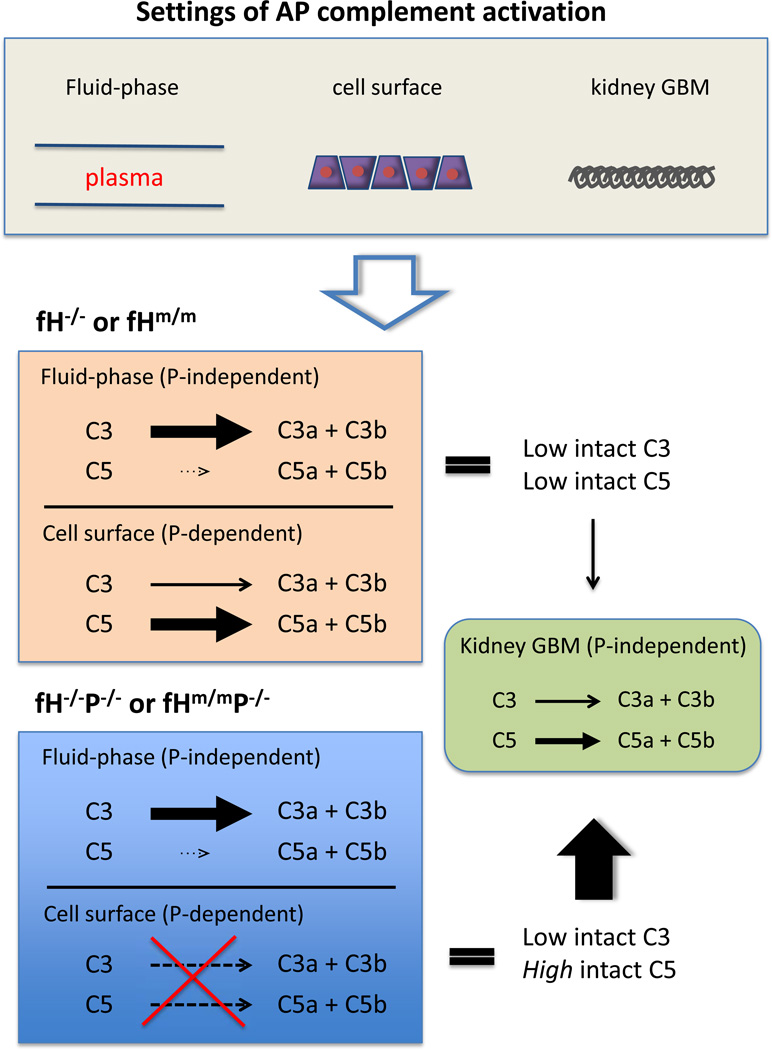

Characterization of the plasma complement profiles of fHm/m/P−/− and fH−/−/P−/− mice revealed a slight reduction in C3 consumption but a marked decrease in C5 consumption compared with their P-sufficient littermates (Lesher et al., 2013; Ruseva et al., 2013) Lesher and Song, unpublished observations). Thus, in fH−/− and fHm/m mice, C5 consumption was largely dependent on P whereas C3 consumption was not. These findings are reminiscent of the effects of P-dependent and P-independent C3NeFs discussed above, with fH−/− and fHm/m mice displaying a complement profile analogous to that caused by P-dependent C3NeFs and fH−/−/P−/− and fHm/m/P−/− mice that of C3-independent C3NeFs (Daha, 2013; Lesher et al., 2013; Ruseva et al., 2013). They also suggested that C3 GN exacerbation in the fH/P double mutant mouse strains may be caused by a change in plasma complement, especially C5 levels. This hypothesis was also supported by the fact that fHm/m/P−/− mice had higher plasma C3 and C5 levels than fH−/−/P−/− mice and they developed lethal C3 GN, all dying prematurely before 3 month old, whereas no early mortality was seen with fH−/−/P−/− mice (Lesher et al., 2013; Ruseva et al., 2013;Lesher and Song, unpublished observations).

The question then is how to explain this seemingly paradoxical effect of P deficiency in fH−/− and fHm/m mice. Based on our experimental data and the known properties of fluid-phase and surface-bound P, C3 and C5 convertases, we propose a model as depicted in Figure 2 to interpret the fHm/m/P−/− and fH−/−/P−/− mouse phenotype. The key hypothesis of this model is that P-independent C3 and C5 activation on the kidney glomerular basement membrane (GBM) contributes to tissue injury, and together with fluid phase generated C3b fragments, causes severe C3 GN. As lethal C3 GN developed in fHm/m/P−/− mice, kidney injury in the double mutant mice must be P-independent. We postulate that since the a cellular GBM lacks plasma membrane-associated complement regulators such as DAF and Crry, fH usually plays an indispensible role in controlling AP complement activation at this site. In the absence of fH, the GBM would be completely unprotected and susceptible to spontaneous, P-independent complement attack. However, AP complement injury of the GBM could have been limited in fH−/− and fHm/m mice due to exhaustive consumption of C3 (mainly in plasma) and C5 (mainly on surface of cells throughout the body) (Figure 2) (Lesher et al., 2013; Ruseva et al., 2013). In fHm/m/P−/− and fH−/−/P−/− mice, consumption of C5 and to some extent C3 on the cell surface was prevented, leading to a moderate increase in plasma C3 and marked increase and availability of C5 to be activated in the GBM, greatly exacerbating renal injury (Figure 2) (Lesher et al., 2013; Ruseva et al., 2013; Lesher and Song, unpublished observations).

Fig 2. Proposed mechanism of C3 GN exacerbation in fHm/m/P−/− and fH−/−/P−/− mice.

In the absence of fH, AP complement is activated in the plasma, on cellular surfaces of multiple tissues and on the kidney glomerular basement membrane (GBM). In fHm/m and fH−/− mice, both C3 and C5 are consumed, primarily in the plasma and on cells of extra-renal tissues, respectively, leaving little C5 activity to cause damage in the renal GBM. C3 turnover in the plasma of fHm/m and fH−/− mice is P-independent, whereas C5 consumption on extra-renal cells is P-dependent. In fHm/m/P−/− and fH−/−/P−/− mice, lack of P activity on the cell surface has a modest effect on C3 consumption but largely prevents C5 consumption, making more C5 available for activation. Increased C5 activation on the GBM, a P-independent process, would account for the exacerbation of C3 GN, presumably due to facile complement activation in the absence of fH and lack of membrane complement inhibitors on the acellular GBM.

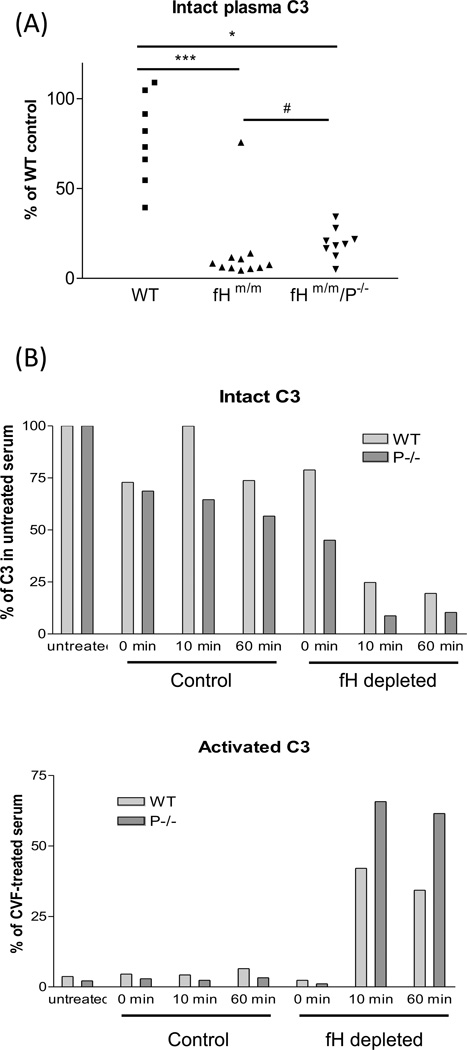

Our proposed model shown in Figure 2 is consistent with data obtained from recent studies of fHm/m/P−/− and fH−/−/P−/− mice and with previously characterized properties of fluid phase and surface-bound P, C3 and C5 convertases. As alluded to above, blocking P function in fHm/m and fH−/− mice only slightly increased plasma intact C3 levels (Lesher et al., 2013; Ruseva et al., 2013) (Figure 3A), suggesting that P is largely dispensable for plasma C3 turnover in the absence of adequate fH control. This conclusion was confirmed by anin vitro experiment showing that depletion of fH by affinity column chromatography from WT and P−/− mouse serum caused a similar degree of C3 consumption (Lesher et al., 2013) (Figure 3B). It is also consistent with findings from earlier biochemical studies by Farries et al who demonstrated high affinity of P to surface-bound C3b and iC3b (C3b > iC3b) but weak or undetectable P binding to fluid phase C3b, iC3b or C3c (Farries et al., 1988). These earlier studies led Farries et al to conclude that P was essentially a stabilizer of surface-bound C3bBb only with minimal regulatory activity on fluid phase C3 convertase (Farries et al., 1988). A second tenet of our model is that consumption of C5 in fHm/m and fH−/− mice by the C5 convertase was P-dependent and primarily occurred on the cell surface (Figure 2). It was well established by previous biochemical studies that fluid-phase C3bBb is primarily a C3 convertase enzyme with very poor activity towards C5 (Rawal and Pangburn, 2001a; Rawal and Pangburn, 1998; Rawal and Pangburn, 2000; Rawal and Pangburn, 2001b). P-dependent C5 activation on the cell surface is also consistent with P being primarily a stabilizer acting on surface-bound C3bBb as discussed above, and presumably on the putative C5 convertase (C3b)2Bb (Gotze and Muller-Eberhard, 1974; Medicus et al., 1976a; Medicus et al., 1976b; Pangburn and Rawal, 2002; Rawal and Pangburn, 1998; Rawal and Pangburn, 2001b). Finally, we assume in our model that extensive cell surface activation of C5 leading to its consumption in fHm/m and fH−/− mice did not result in extra-renal injury because potentially injurious effect of C5 activation was dissipated among all the tissues, whereas in fHm/m/P−/− and fH−/−/P−/− mice there was increased C3 and C5 availability and their activation was concentrated on the kidney GBM (Figure 2).

Fig 3. P is not required for fluid-phase C3 turnover in the absence of adequate fH control of AP complement activation.

(A). Compared with wild-type (WT) mice, fHm/m mice had very low plasma levels of intact C3 (***p<0.001). Gene deletion of P from fHm/m mice did not prevent C3 turnover as fHm/m/P−/− mice also had very low plasma levels of intact C3 (*p<0.05, comparing with WT mice). However, plasma levels of intact C3 in fHm/m/P−/− mice were slightly raised (#p=0.023, Mann-Whitney test comparing with fHm/m mice), possibly reflecting abrogation of surface C3bBb activity. (B)C3 activation in fH-depleted mouse serum is properdin-independent. WT (light gray bars) and P−/− (dark gray bars) mouse serum incurred similar time-dependent C3 activation after passing through an anti-fH mAb column to deplete fH (fH depleted) but not after passing through a control mAb column (control). Values for activated C3 were normalized to a reference serum sample activated by cobra venom factor (CVF), and intact C3 was normalized to C3 in the original serum before affinity column processing. Data are taken from Lesher et al., 2013 with permission.

Summary and conclusions

Almost six decades after its discovery, the mechanism of action of P in complement activation and its relevance to human health and disease still intrigues us. Based on recent studies, the role of P in AP complement activation should be viewed as a stabilizer of preformed C3bBb convertase on the cell surface, as well as a platform to recruit and assemble new C3bBb complexes. Binding of P to the cell surface to serve as a platform for new C3 convertase formation is primarily through surface deposited C3b, although C3-independent binding, e.g. via glycosaminoglycans, may also be possible. Given its oligomeric nature, the two roles of P are likely to be closely intertwined, i.e. a single P oligomer may stabilize one C3bBb and simultaneously recruit and assembly another C3bBb complex. A distinguishing feature of this model of P function is that it conceptualizes that C3bBb can be recruited and attached to the cell surface via non-covalent interaction with P, rather than through covalent bonding of C3b with surface NH2 or hydroxyl groups.

The role of P in the pathogenesis of AP complement-mediated human disorders and the feasibility, efficacy and safety of therapeutic targeting of in these diseases requires further study. The context-dependent requirement of P in AP complement activation on pathogens and autologous cells provides both opportunities and challenges. The fact that not all microbial activation of AP complement requires P suggests that therapeutic targeting of P may produce less side effects in comprising host defense than the inhibition of other components of the AP. On the other hand, the finding that P does not regulate AP complement activation in the fluid phase and may be required on some but not all cellular or tissue surfaces demands that therapeutic targeting of P be carefully evaluated to achieve efficacy and avoid untoward effect such as seen in the fHm/m and fH−/− murine C3 glomerulopathy models.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agarwal S, Ferreira VP, Cortes C, Pangburn MK, Rice PA, Ram S. An evaluation of the role of properdin in alternative pathway activation on Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Immunol. 2010;185:507–516. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S, Specht CA, Haibin H, Ostroff GR, Ram S, Rice PA, Levitz SM. Linkage specificity and role of properdin in activation of the alternative complement pathway by fungal glycans. mBio. 2011:2. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00178-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camous L, Roumenina L, Bigot S, Brachemi S, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Lesavre P, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. Complement alternative pathway acts as a positive feedback amplification of neutrophil activation. Blood. 2011;117:1340–1349. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-283564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clardy CW, Forristal J, Strife CF, West CD. A properdin dependent nephritic factor slowly activating C3, C5, and C9 in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, types I and III. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1989;50:333–347. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(89)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes C, Ferreira VP, Pangburn MK. Native properdin binds to Chlamydia pneumoniae and promotes complement activation. Infect Immun. 2011;79:724–731. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00980-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daha MR. Unexpected role for properdin in complement C3 glomerulopathies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:5–7. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cordoba SR, de Jorge EG. Translational mini-review series on complement factor H: genetics and disease associations of human complement factor H. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;151:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova P, Ivanovska N, Belenska L, Milanova V, Schwaeble W, Stover C. Abrogated RANKL expression in properdin-deficient mice is associated with better outcome from collagen-antibody-induced arthritis. Arthritis research & therapy. 2012;14:R173. doi: 10.1186/ar3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova P, Ivanovska N, Schwaeble W, Gyurkovska V, Stover C. The role of properdin in murine zymosan-induced arthritis. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:1458–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkelberger JR, Song WC. Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Res. 2010;20:34–50. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhouri F, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Noel LH, Cook HT, Pickering MC. C3 glomerulopathy: a new classification. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6:494–499. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farries TC, Finch JT, Lachmann PJ, Harrison RA. Resolution and analysis of 'native' and 'activated' properdin. Biochem J. 1987;243:507–517. doi: 10.1042/bj2430507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farries TC, Lachmann PJ, Harrison RA. Analysis of the interactions between properdin, the third component of complement (C3), and its physiological activation products. Biochem J. 1988;252:47–54. doi: 10.1042/bj2520047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon DT, Austen KF. Properdin: binding to C3b and stabilization of the C3b-dependent C3 convertase. J Exp Med. 1975;142:856–863. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.4.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira VP, Cortes C, Pangburn MK. Native polymeric forms of properdin selectively bind to targets and promote activation of the alternative pathway of complement. Immunobiology. 2010;215:932–940. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fijen CAP, van den Bogaard R, Schipper M, Mannens M, Schlesinger M, Nordin FG, Dankert J, Daha MR, Sjöholm AG, Truedsson L, Kuijper EJ. Properdin deficiency: molecular basis and disease association. Mol Immunol. 1999;36:863–867. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaarkeuken H, Siezenga MA, Zuidwijk K, van Kooten C, Rabelink TJ, Daha MR, Berger SP. Complement activation by tubular cells is mediated by properdin binding. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1397–E1403. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90313.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotze O, Muller-Eberhard HJ. The role of properdin in the alternate pathway of complement activation. J Exp Med. 1974;139:44–57. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou SJ, Yuan J, Chen M, Yu F, Zhao MH. Circulating complement activation in patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Kidney Int. 2013;83:129–137. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati S, Agarwal S, Vasudhev S, Rice PA, Ram S. Properdin is critical for antibody-dependent bactericidal activity against Neisseria gonorrhoeae that recruit C4b-binding protein. J Immunol. 2012;188:3416–3425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta-Bansal R, Parent JB, Brunden KR. Inhibition of complement alternative pathway function with anti-properdin monoclonal antibodies. Mol Immunol. 2000;37:191–201. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(00)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harboe M, Garred P, Karlstrom E, Lindstad JK, Stahl GL, Mollnes TE. The down-stream effects of mannan-induced lectin complement pathway activation depend quantitatively on alternative pathway amplification. Mol Immunol. 2009;47:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harboe M, Garred P, Lindstad JK, Pharo A, Muller F, Stahl GL, Lambris JD, Mollnes TE. The role of properdin in zymosan- and Escherichia coli-induced complement activation. J Immunol. 2012;189:2606–2613. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinen S, Pluthero FG, van Eimeren VF, Quaggin SE, Licht C. Monitoring and modeling treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Mol Immunol. 2013;54:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holers VM. The spectrum of complement alternative pathway-mediated diseases. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:300–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourcade DE. The role of properdin in the assembly of the alternative pathway C3 convertases of complement. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2128–2132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingwer I, Petersen BH, Brooks G. Serum bactericidal action and activation of the classic and alternate complement pathways by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 1978;92:211–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper C, Atkinson JP, Hourcade DE. Properdin: emerging roles of a pattern-recognition molecule. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:131–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper C, Mitchell LM, Zhang L, Hourcade DE. The complement protein properdin binds apoptotic T cells and promotes complement activation and phagocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9023–9028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801015105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y, Miwa T, Zhou L, Song WC. Activator-specific requirement of properdin in the initiation and amplification of the alternative pathway complement. Blood. 2008;111:732–740. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y, Zhou L, Miwa T, Song WC. Genetic and therapeutic targeting of properdin in mice prevents complement-mediated tissue injury. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3545–3554. doi: 10.1172/JCI41782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann PJ. The Amplification Loop of the Complement Pathways. Vol. 104. Academic Press; 2009. pp. 115–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesher AM, Zhou L, Kimura Y, Sato S, Gullipalli D, Herbert AP, Barlow PN, Eberhart HU, Skerka C, Zipfel PF, Hamano T, Miwa T, Tung KS, WC S. Combination of factor H mutation and properdin deficiency causes severe C3 glomerulopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:53–65. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012060570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liszewski MK, Farries TC, Lubun DM, Rooney IA, Atkinson JP, Frank JD. Control of the Complement System. Vol. Volume 61. Academic Press; 1996. pp. 201–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Barricarte R, Heurich M, Valdes-Canedo F, Vazquez-Martul E, Torreira E, Montes T, Tortajada A, Pinto S, Lopez-Trascasa M, Morgan BP, Llorca O, Harris CL, Rodiguez de Cordoba S. Human C3 mutation reveals a mechanism of dense deposit disease pathogenesis and provides insights into complement activation and regulation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3702–3712. doi: 10.1172/JCI43343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maves KK, Weiler JM. Properdin: approaching four decades of research. Immunologic research. 1993;12:233–243. doi: 10.1007/BF02918255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicus RG, Gotze O, Muller-Eberhard HJ. Alternative pathway of complement: recruitment of precursor properdin by the labile C3/C5 convertase and the potentiation of the pathway. J Exp Med. 1976a;144:1076–1093. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.4.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicus RG, Götze O, Müller-Eberhard HJ. Activation of Properdin (P) and Assembly and Regulation of the Alternative Pathway C5 Convertase. J Immunol. 1976b;116:1741–1742. [Google Scholar]

- Miwa T, Sato S, Gullipalli D, Nangaku M, Song WC. Blocking properdin and the alternative pathway complement ameliorates renal ischemia reperfusion injury in decay-accelerating factor and CD59 double knockout mice. J Immunol. 2012;189:5434–5441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa T, Zhou L, Hilliard B, Molina H, Song WC. Crry, but not CD59 and DAF, is indispensable for murine erythrocyte protection in vivo from spontaneous complement attack. Blood. 2002;99:3707–3716. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollnes TE, Ng YC, Peters DK, Lea T, Tschopp J, Harboe M. Effect of nephritic factor on C3 and on the terminal pathway of complement in vivo and in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;65:73–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangburn MK. Analysis of the natural polymeric forms of human properdin and their functions in complement activation. J Immunol. 1989;142:202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangburn MK. Host recognition and target differentiation by factor H, a regulator of the alternative pathway of complement. Immunopharmacology. 2000;49:149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)80300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangburn MK, Muller-Eberhard HJ. Initiation of the alternative complement pathway due to spontaneous hydrolysis of the thioester of C3. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1983;421:291–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1983.tb18116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangburn MK, Muller-Eberhard HJ. The C3 convertase of the alternative pathway of human complement. Enzymic properties of the bimolecular proteinase. Biochem J. 1986;235:723–730. doi: 10.1042/bj2350723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangburn MK, Rawal N. Structure and function of complement C5 convertase enzymes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:1006–1010. doi: 10.1042/bst0301006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MC, Cook HT, Warren J, Bygrave AE, Moss J, Walport MJ, Botto M. Uncontrolled C3 activation causes membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in mice deficient in complement factor H. Nat Genet. 2002;31:424–428. doi: 10.1038/ng912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer L, Blum L, Lepow IH, Ross OA, Todd EW, Wardlaw AC. The properdin system and immunity. I. Demonstration and isolation of a new serum protein, properdin, and its role in immune phenomena. Science. 1954;120:279–285. doi: 10.1126/science.120.3112.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram S, Cullinane M, Blom AM, Gulati S, McQuillen DP, Monks BG, O'Connell C, Boden R, Elkins C, Pangburn MK, Dahlback B, Rice PA. Binding of C4b-binding protein to porin: a molecular mechanism of serum resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Exp Med. 2001;193:281–295. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram S, McQuillen DP, Gulati S, Elkins C, Pangburn MK, Rice PA. Binding of complement factor H to loop 5 of porin protein 1A: a molecular mechanism of serum resistance of nonsialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Exp Med. 1998;188:671–680. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawal N, Pangburn M. Formation of high-affinity C5 convertases of the alternative pathway of complement. J Immunol. 2001a;166:2635–2642. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawal N, Pangburn MK. C5 convertase of the alternative pathway of complement. Kinetic analysis of the free and surface-bound forms of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16828–16835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawal N, Pangburn MK. Functional role of the noncatalytic subunit of complement C5 convertase. J Immunol. 2000;164:1379–1385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawal N, Pangburn MK. Structure/function of C5 convertases of complement. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001b;1:415–422. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(00)00039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruseva MM, Vernon KA, Lesher AM, Schwaeble WJ, Youssif MA, Botto M, Cook HT, Song WC, Stover CM, Pickering MC. Loss of properdin exacerbates C3 glomerulopathy resulting from factor H deficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:43–52. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012060571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt CQ, Herbert AP, Hocking HG, Uhrin D, Barlow PN. Translational mini-review series on complement factor H: structural and functional correlations for factor H. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;151:14–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaeble WJ, Reid KB. Does properdin crosslink the cellular and the humoral immune response? Immunol Today. 1999;20:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01376-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servais A, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Lequintrec M, Salomon R, Blouin J, Knebelmann B, Grunfeld JP, Lesavre P, Noel LH, Fakhouri F. Primary glomerulonephritis with isolated C3 deposits: a new entity which shares common genetic risk factors with haemolytic uraemic syndrome. J Med Genet. 2007;44:193–199. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.045328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servais A, Noel LH, Roumenina LT, Le Quintrec M, Ngo S, Dragon-Durey MA, Macher MA, Zuber J, Karras A, Provot F, Moulin B, Grunfeld JP, Niaudet P, Lesavre P, Fremeaux-Bacchi V. Acquired and genetic complement abnormalities play a critical role in dense deposit disease and other C3 glomerulopathies. Kidney Int. 2012;82:454–464. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC, Zhang Y, Nasr SH, Leung N, Vrana J, Cramer C, Nester CM, Smith RJ. Proliferative glomerulonephritis secondary to dysfunction of the alternative pathway of complement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1009–1017. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07110810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ, Harris CL, Pickering MC. Dense deposit disease. Mol Immunol. 2011;48:1604–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer D, Mitchell LM, Atkinson JP, Hourcade DE. Properdin can initiate complement activation by binding specific target surfaces and providing a platform for de novo convertase assembly. J Immunol. 2007;179:2600–2608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover CM, Luckett JC, Echtenacher B, Dupont A, Figgitt SE, Brown J, Mannel DN, Schwaeble WJ. Properdin plays a protective role in polymicrobial septic peritonitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:3313–3318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel S, Zimmering M, Papp K, Prechl J, Jozsi M. Anti-factor B autoantibody in dense deposit disease. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:1476–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanuma Y, Ohi H, Hatano M. Two types of C3 nephritic factor: properdin-dependent C3NeF and properdin-independent C3NeF. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;56:226–238. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90144-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Winterborn MH. Hypocomplementaemia due to a genetic deficiency of beta 1H globulin. Clin Exp Immunol. 1981;46:110–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varade WS, Forristal J, West CD. Patterns of complement activation in idiopathic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, types I, II, and III. Am J Kidney Dis. 1990;16:196–206. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)81018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirthmueller U, Dewald B, Thelen M, Schafer MK, Stover C, Whaley K, North J, Eggleton P, Reid KB, Schwaeble WJ. Properdin, a positive regulator of complement activation, is released from secondary granules of stimulated peripheral blood neutrophils. J Immunol. 1997;158:4444–4451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Schreiber A, Heeringa P, Falk RJ, Jennette JC. Alternative complement pathway in the pathogenesis of disease mediated by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:52–64. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Mao D, Holers VM, Palanca B, Cheng AM, Molina H. A critical role for murine complement regulator crry in fetomaternal tolerance. Science. 2000;287:498–501. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Berger SP, Trouw LA, de Boer HC, Schlagwein N, Mutsaers C, Daha MR, van Kooten C. Properdin binds to late apoptotic and necrotic cells independently of C3b and regulates alternative pathway complement activation. J Immunol. 2008;180:7613–7621. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki R, Koshino H, Kurono S, Nishinaka Y, McQuillen DP, Kume A, Gulati S, Rice PA. Structural and immunochemical characterization of a Neisseria gonorrhoeae epitope defined by a monoclonal antibody 2C7; the antibody recognizes a conserved epitope on specific lipooligosaccharides in spite of the presence of human carbohydrate epitopes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36550–36558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaferani A, Vives RR, van der Pol P, Hakvoort JJ, Navis GJ, van Goor H, Daha MR, Lortat-Jacob H, Seelen MA, van den Born J. Identification of tubular heparan sulfate as a docking platform for the alternative complement component properdin in proteinuric renal disease. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:5359–5367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaferani A, Vives RR, van der Pol P, Navis GJ, Daha MR, van Kooten C, Lortat-Jacob H, Seelen MA, van den Born J. Factor h and properdin recognize different epitopes on renal tubular epithelial heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:31471–31481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Meyer NC, Wang K, Nishimura C, Frees K, Jones M, Katz LM, Sethi S, Smith RJ. Causes of alternative pathway dysregulation in dense deposit disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:265–274. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07900811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HF, Yan H, Stover CM, Fernandez TM, Rodriguez de Cordoba S, Song WC, Wu XT, R W, Schwaeble WJ, Atkinson JP, Hourcade DE, Pham CT. Antibody directs properdin-dependent complement alternative pathway activation in a mouse model of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E415–E422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]