Abstract

Stress has many biological effects on human daily life. In the present study, dietary protein intake was correlated with the investigated stress levels of nurses and housewives of the targeted urban population. Age group ranged from 30 to 45 years and both the groups belonged to middle socioeconomic status. After calculations of environmental, psychological and physiological stresses, it was observed that the levels of stress in housewives were significantly higher than those of nurses. Recommended dietary allowances, RDA and actual protein intakes, API were also compared in both the groups. The found protein intake was less in housewives as compared to that of nurses.

Keywords: Protein, Stress, Nurses, Housewives

1. Introduction

Stress, for many years, has been recognized as a source of physical and mental health impairment (Cooper and Payne, 1988; Karasek and Theorell, 1990; Memon et al., 2003). There are evidences in the literature that stress may reduce the effectiveness of human immune system and increase the risk of infections and diseases (Dhabhar et al., 1996). Stressors, even the short-term, can produce demonstrable physiological changes in heart rate, blood pressure and activation of the neutrophils (Ellard et al., 2001). The activated neutrophils release many mediators, which can potentially damage healthy tissues and organs. The neutrophils, when activated, release many biologically active compounds, such as cationic proteins, myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, acid hydrolases, lactoferrin (an iron binding protein), B12-binding protein, cytochrome b and collagenase (Abramson and Wheeler, 1993).

Epidemiological studies have provided data to support the idea that those individuals who are more stressed are prone to opportunistic infections (David and Andrew, 2000). Stress associated with family dysfunction has been reported to be significantly associated with increased incidence of upper respiratory tract infection and influenza. Accumulation of stress has been associated with chronic immunosuppression (Emma et al., 1997). Acute stressors have also been reported to increase the number of circulating leukocytes which significantly affect erythron variables such as hematocrit (Hct), mean cell Hb content and the number of red blood cells (Dhabhar et al., 1996). It is also reported that maturation of the central nervous system and consequent behavior depend on several major factors such as, heredity, i.e., genetic directives, complexity and degree of environmental stimulation and availability of adequate and balanced diet (Van Gelder, 1990; Morgane et al., 1993).

Malnutrition, one of the primary non-genetic factors affecting the developing brain, has long been thought to adversely alter the organism’s ability to interact and cope with its environment (Howe, 1981; Memon and Memon, 1999). Proteins, the most abundant compounds in serum, have their involvement in enzymes, hormones, antibodies, osmotic pressure balance, maintaining acid-base balance and as a reserve source of nutrition for the body’s tissues and muscles. Decreased levels of proteins may be due to poor nutrition, liver disease, malabsorption, diarrhea, or severe burns. Increased levels have been seen in lupus, liver disease, chronic infections, alcoholism, leukemia and tuberculosis patients (Smith et al., 1995; Offringa, 1998).

Stress in Pakistani population is quite different from other population of the world because of differences in their life style, socioeconomic status, environment and culture. However, to our knowledge, there is no published study on the significance of protein intake and stress in the female Pakistani population. The objective of this study is to examine the correlation of protein intake and stress levels in Pakistani female population and for this, nurses and housewives were selected as targeted model population.

2. Material and methods

The present study was performed at the Institute of Biochemistry, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan. Ethical Committee of the institute approved the study plan. Informed consent was taken from all the participants included in this study. This study was conducted during the year 2004–2005.

2.1. General considerations

2.1.1. Evaluation of stress

A questionnaire was designed to measure the environmental, psychological and physiological stresses (Ansari, 1980; Feroza, 2006). The method of scoring was based on eight-point likert scale. The authors filled in these questionnaires for 80 nurses and 80 housewives of the same area. Age group of both the classes ranged between 30 and 45 years and both the classes belonged to middle socioeconomic status.

2.1.2. Nutritional assessment

In order to access the effect of different nutrients on stress, a separate questionnaire (Memon et al., 2002; Feroza, 2006) was used. No subject was found to have diabetes. This questionnaire was filled in for each individual in both the groups, in which age, height, weight, marital status, socioeconomic status and diet patterns were recorded. For recommended dietary allowance, RDA formula (Howe, 1981) was used for the calculation of energy giving nutrients in food of both the groups. Actual protein intake, API, was calculated from the table of nutritive values of food (Mahan and Escott-Stump, 2008).

2.1.3. Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measurements were conducted using the standard methods (Stensland and Margolis, 1990; Wattoo et al., 2010). Weight with minimum clothing was recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg, using a portable digital scale (Tanita model 1597; Tanita, Tokyo, Japan). For height, the subject stood straight for measurement to the nearest 1 mm. The body mass index, BMI, was calculated as weight divided by the square of height (kg/m2).

2.2. Biochemical measurements

2.2.1. Sample collection

Blood samples were collected in the morning by disposable syringes through vein puncture and a maximum of 5 ml blood was taken for the analysis of total protein and albumin levels. Serum samples were immediately transferred to diagnostic laboratory, Institute of Biochemistry, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, which took about 1 h after collection. All blood samples were analyzed using ‘Merck-lab 200’ instrument, Germany, by using the prescribed standard procedures/methods given in the instrument operational manual of the company.

2.2.2. Biochemical methods

Total protein levels were measured by Biuret method (Gornall et al., 1949). Albumin levels were measured by BCG method (Rodkey, 1965; Lynch, 1969).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Means of two groups were compared by using Student’s t-test or analysis of variance. The results were considered statistically significant and the p value was less than 0.001. Data in this study were analyzed by the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

Demographic and professional characteristics of responding nurses and housewives are given in Table 1. 33% of nurses are <30 years of age, 55.5% are in between 30 and 40 years, and 11.5% are of 40 years. 10% of housewives are <30 years, 76.9% are 30–40 years and 13.1% females of this group are above 40 years of age. The mean BMI in kg/m2 of nurses is 25 ± 3.9, while the mean BMI of housewives is 24.2 ± 2.0. There is no female with a BMI greater than 30.0.

Table 1.

Demographic and professional characteristics of responding nurses and housewives.

| Variables | Nurses | Housewives | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | n = 80 | n = 80 | |

| Socioeconomic condition (SEC) | Middle socioeconomic | ||

| Age (years) | ⩽30 | 33% | 10% |

| 30–40 | 55.5% | 76.9% | |

| ⩾45 | 11.5% | 13.1% | |

| Weight (kg) | 51.7 ± 4.9 | 53.8 ± 4.9 | |

| Height (cm) | 145.4 ± 8.1 | 149 ± 2.9 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25 ± 3.9 | 24.2 ± 2.0 | |

| BMI > 25 (kg/m2) | 32.5% | 37.4% | |

| BMI < 25 (kg/m2) | 67.5% | 62.5% | |

Data was shown as mean ± SD, Percentage of subjects with BMI > 25 (kg/m2) and BMI < 25 (kg/m2), respectively.

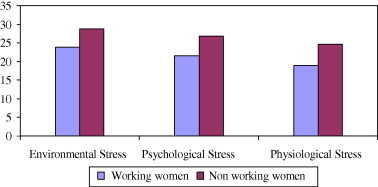

Results of the statistical analysis (Table 2) have revealed the mean difference between the three types of stresses, i.e., environmental stress (t = 7.2), psychological stress (t = 8.5) and physiological stress (t = 4.5). The probability is 0.001, which indicates that there is a significant difference between the level of stress of nurses and housewives. The mean levels of three different stresses are also shown graphically in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Statistical comparison of stress in nurses and housewives.

| Stress | Nurses n = 80 mean ± SD | Housewives n = 80 mean ± SD | t-test | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | 23.8 ± 3.9 | 28.8 ± 4.8 | 7.2 | 0.001 |

| Psychological | 21.6 ± 2.9 | 26.7 ± 4.5 | 8.5 | 0.001 |

| Physiological | 19 ± 3.7 | 24.8 ± 4.5 | 4.5 | 0.001 |

Figure 1.

Comparison of environmental, psychological and physiological stress in nurses (working women) and housewives (non-working women).

Recommended dietary allowance, RDA and actual protein intake of nurses and housewives are shown in Table 3. Mean values of RDA for nurses are in the range from 203 to 270 kcal, while the actual protein intake is from 127 to 192 kcal. In housewives the mean RDA values of protein are 202–275 kcal and the actual intake of protein is in the range between 90 and 165 kcal. The actual protein intake by both the groups is very low compared to their RDA values. The results show that overall housewives have low protein intake than the nurses.

Table 3.

Comparison of RDA and actual protein intake between nurses and housewives.

| Subjects | Statistical results | Caloric requirement according to RDA (kcal) | Actual caloric intake (kcal) | Difference between RDA and caloric intake (kcal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses | Mean ± SD | 239 ± 27.6 | 160 ± 23.5 | 79 ± 4.1 |

| Range | 203–270 | 127–192 | 76–88 | |

| Housewives | Mean ± SD | 232 ± 28.5 | 123 ± 24.5 | 109 ± 4 |

| Range | 202–75 | 90–165 | 112–110 |

Total protein, albumin and A/G ratio in nurses and housewives are shown in Table 4. Mean value of total protein in nurses is in the range of 5.1–8.1 g/dl with the mean of 6.9 ± 0.8 g/dl and in housewives the range is 5.1–8.0 g/dl with the mean of 6.0 ± 0.6 g/dl. The mean value of albumin is 3.1 ± 0.3 g/dl in nurses where as in housewives it is 2.8 ± 0.2 g/dl. In nurses the range of A/G ratio is 2.6–4.2 g/dl with the mean of 3.8 ± 0.5 g/dl while the mean A/G ratio in housewives is 3.2 ± 0.4 and the range is 2.6–4.1 g/dl. Observed values of t-test and probability are not significant. In both the groups, albumin and A/G ratio are in the normal range.

Table 4.

Comparison of total protein, albumin and A/G ratio in nurses and housewives.

| Subjects | Statistical results | Total protein (g/dl) | Albumin (g/dl) | A/G ratio (g/dl) | t-test | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses n = 80 | Mean ± SD | 6.9 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Range | 5.1–8.1 | 2.5–3.9 | 2.6–4.2 | |||

| Housewives n = 80 | Mean ± SD | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | ||

| Range | 5.1–8 | 2.5–3.9 | 2.6–4.1 |

4. Discussion

Workingwomen group (nurses) are capable of raising children, doing household work, entertaining the guests and at the same time-sharing their husband’s financial responsibilities. The feeling in turn tends to enhance their satisfaction and may be due to this that she suffers less depression, as compared to housewives who become a victim of boredom and monotony (Booth, 1979). Mitchell and Oakley (1976) reported that the housework is considered to be of low status and isolating, and full time housewives tend to be less happy with their lives and in turn more depressed than working women. They also reported that work is often good for us; it allows us to develop new skills, enhance self-esteem, increasing our feelings for competence and self-efficiency. There are also a good number of studies that indicate the positive impact of women’s employment on marriage (Philip, 2002).

Malnutrition is a major health problem in Pakistan that affects women’s health. The role of education is an important theme in many intervention strategies to modify dietary habits. Smith et al. (1995) reported that nutrition education is recommended to provide guidance for choosing healthy diets. Housewives do not take required food due to shortage of time and remain unaware as compared to the working women, who are aware of all information about their food.

Although these results (Table 4) reveal no significant differences between both the groups; however, housewives have low total protein levels in comparison to the nurses. This perhaps might be due to their low protein intake. In stress conditions the requirements of nutrients are increased. Under severe physical stress, such as burns, trauma fever or surgeries, the requirement of calories is increased by 50% or more (Emma et al., 1997; Wattoo et al., 2007).

In response to stressors, the hypothalamus signals the release of the catabolic hormones, glucocorticoids, catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) and glucagon. These hormones cause increased protein catabolism, gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis and lipolysis, with a resulting loss of adipose and lean body tissues. If the stress is of brief duration, the changes in stress hormone levels are short lived and unlikely to produce a catabolic response. On the other hand, if the stressor is intense and prolonged, a catabolic state with the loss of nitrogen occurs (Feroza, 2006; Wattoo et al., 2008).

Protein catabolism is a normal response to stress and cannot be prevented, although an adequate intake can help to replenish the lost protein. Nitrogen losses usually peak five to ten days after the stress. Serotonin inhibits stress, eating by controlling the alarm hormone serotonin and can be increased choosing tryptophan rich food. Protein supplies the body with the important amino acids needed for mental health (Emma et al., 1997; Wattoo et al., 2007).

5. Conclusion

In the current conducted study, housewives are under more stress compared to nurses. Nutritional assessment of both the groups revealed that protein intake is generally lower than the RDA and is approximately half of their recommended values. Protein level is also less in housewives as compared to the nurses. The observed levels of albumin and A/G ratio are in the normal range in both the groups. This study may be helpful for policy measures to educate the general public who are mostly considering that working counterparts are more stressful than the non-working individuals.

Acknowledgments

This study is the part of project titled ‘Effect of stress and nutrition on biochemical constituents of working and non-working females in different ethnic groups of Hyderabad district’. Authors are thankful to Director, Institute of Biochemistry, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan, for providing funds and essential laboratory facilities for this project.

References

- Abramson J.S., Wheeler J.G. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1993. The Neutrophil: Natural Immune System. pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari Z.A. Study habits and attitudes of students: development and validation of questionnaire measures. Quaid-i-Azam Univ; Islamabad, Pakistan: 1980. (Nat. Inst. Psychol). [Google Scholar]

- Booth A. Does wives’ employment cause stress for husbands? Fam. Coordinator. 1979;28:445–449. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C., Payne R., editors. Causes Coping and Consequences of Stress at Work. John Wiley and Sons, NY; Chichester: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- David A.S.R., Andrew W.T. Assessing the role of nutritional stress in the decline of wild populations: a steller case of scientific sleuthing. Proc. Comp. Nutr. Soc. 2000:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar F.S., Miller A.H., McEven B.S., Spencer R.L. Stress induced changes in blood leukocyte distribution. J. Immunol. 1996;157:1638–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellard D.R., Castle P.C., Mian R. Effect of a short term mental stressor on neutrophil activation. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2001;41:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emma S.W., Donna H.M., Corinne H.R. eighth ed. Prentice Hall; NY: 1997. Robinson’s Basic Nutrition and Diet Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Feroza, 2006, Effect of stress and nutrition on biochemical constituents of working and non-working females in different ethnic groups of Hyderabad district, Ph.D. thesis, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan.

- Gornall A.G., Bardawell C.J.V., David M.M. Determination of serum proteins by means of the biuret reaction. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1949;177:751–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe P.S. seventh ed. W.B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia, London: 1981. Basic Nutrition in Health and Disease. pp. 406–459. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R., Theorell T. Basic Books; New York: 1990. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity and The Reconstruction of Working Life. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M.J. second ed. W.B. Saunders Co; Philedelphia: 1969. Medical Laboratory Technology and Clinical Pathology. p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- Mahan L.K., Escott-Stump S. 12th ed. W.B. Saunders Co.; Philadelphia: 2008. Krause’s Food and Nutrition Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, F., Memon, M.S., 1999. Comparison of emotional status of health and nutrition of working and non-working females in Sindh, Pakistan. In: Proceedings of the 10th National Chemistry Conference Country Coordination Centre for Chemical Sciences, Quaid-i-Azam Univ., Islamabad, Pakistan, pp. 111–114.

- Memon F., Memon M.S., Memon A.N. Study of stress in working and non-working women in Sindh, Pakistan. Pak. J. Anal. Chem. 2002;3:85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Memon F., Memon M.S., Memon A.N., Wattoo M.H.S., Khand F.D. Correlation of stress and blood glucose level in working women and housewives in Sindh, Pakistan. Pak. J. Med. Res. 2003;42:82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J., Oakley A., editors. The Rights and Wrongs of Women. Penguin London and Pantheon Books; USA: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Morgane P.J., Austin-LaFrance R.J., Bronzino J.D., Tonkiss J., Diaz-Cintra S., Cintra L., Kemper T., Galler J.R. Prenatal malnutrition and development of the brain. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1993;17:91–128. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offringa M. Excess mortality after human albumin administration in critically ill patients. Clinical and pathophysiological evidence suggests albumin is harmful. BMJ. 1998;317:223–224. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7153.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip T. Impact of women’s employment on family and marriage: a survey of literature. Soc. Change. 2002;32:46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rodkey F.L. Direct spectrophotometric determination of albumin in human serum. Clin. Chem. 1965;11:478–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A.M., Baghurst K.I., Owen N. Dietary behaviours of volunteers for a nutrition education program, compared with a population sample. Aust. J. Public Health. 1995;19:64–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1995.tb00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensland S.H., Margolis S. Simplifying the calculation of body mass index for quick reference. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 1990;90:856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gelder N.M. Neuronal discharge hypersynchrony and the intracranial water balance in relation to glutamic acid and taurine redistribution: migraine and epilepsy. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1990;351:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattoo F.H., Memon M.S., Memon A.N., Wattoo M.H.S., Ghanghro A.B., Yaquib M., Tirmizi S.A. Effect of stress on serum cholesterol levels in nurses and housewives of Hyderabad, Pakistan. Pak. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;43:50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wattoo F.H., Memon M.S., Memon A.N., Wattoo M.H.S., Tirmizi S.A., Iqbal J. Quantitative analysis of stress and cholesterol levels in university teachers and housewives in Hyderabad, Pakistan. Pak. J. Med. Res. 2007;46:42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattoo F.H., Memon M.S., Memon A.N., Wattoo M.H.S., Tirmizi S.A., Iqbal J. Estimation and correlation of stress and cholesterol level in college teachers and housewives in Hyderabad, Pakistan. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2008;58:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]