Abstract

Exogenous and endogenous stages of Eimeria perforans naturally infected rabbits in Saudi Arabia were described. The prevalence of infection was 75%. Oocysts were ovoid to elliptical and measured 16 × 10 μm. The four dizoic sporocysts were ovoid and measured 7 × 5 μm. Endogenous stages were restricted to the duodenum. Meronts, microgamonts, macrogamonts and young oocysts were recorded and described.

Keywords: Eimeria perforans, Rabbit, Endogenous stages, Saudi Arabia

1. Introduction

The coccidia of the genus Eimeria are the most common parasites of the rabbit and are responsible for major pathogenicity in their host (Coudert, 1989; Licois and Coudert, 1982; Ceré et al., 1996). Fourteen of the 15 species described are known to infect the intestine of this animal (Li and Ooi, 2009). The rabbit intestinal coccidia parasitize distinct parts of the intestine and in different depths of the mucosa (Pakandl, 2009). According to the site of development, Eimeria perforans was known to develop in duodenum and classified as slightly pathogenic species (Pakandl, 2009). The endogenous stages of this parasite were studied for the first time by Scholtyseck et al. (1966). To date, three parasitological and epidemiological studies have been conducted to identify different Eimeria species in domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Saudi Arabia. These studies are those of Kasim and Al-Shawa (1987), Toula and Ramadan (1998) and Bashtar et al. (2003). There were only two studies carried out on the endogenous stages of Eimeria magana infecting rabbits in Saudi Arabia. These studies were conduct by Shazly et al. (2005) and Al-Ghamdy et al. (2005). Due to the scarce knowledge on the endogenous stage of Eimeria infecting rabbits in Saudi Arabia, the present study was suggested. The purpose of the present study is to investigate the prevalence, exogenous and endogenous stages of E. perforans naturally infecting domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Saudi Arabia.

2. Materials and methods

A total of 20 domestic rabbits were collected from rabbit markets in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. At necropsy, duodenum was removed and their continents were subjected to examination for Eimeria infection. Positive samples were subjected to floatation technique (Long et al., 1976) to collect and concentrate the oocysts. The collected oocysts were transferred into 2.5% aqueous potassium dichromate solution (w/v) and incubated at 25–28 °C to allow the oocysts to sporulate and examined periodically to determine the sporulation time. The morphological features of sporulated oocysts including shape, shape index, size, inner and outer wall, micropyle and residuum were recorded. To study the endogenous stages, duodenums of the infected animals were then fixed in 10% neutral puffer formalin. Histological sections of tissues embedded in paraffin wax were cut at 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Stained sections were examined and photographed using photo research Olympus microscope equipped by a DP 25 digital camera. All measurements of oocysts and endogenous stages were given in micrometers (μm) and represent mean values of at least 30 measurements.

3. Results

Twenty rabbits were examined; fifteen of them were found infected. Initially, the oocysts were non-sporulated, while 90% sporulated by 24 h at 25 ± 3 °C.

4. Oocyst description

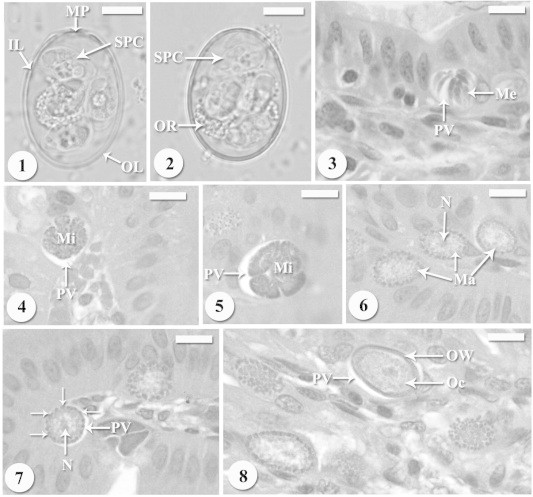

The oocysts are transparent and ovoid to ellipsoidal in shape (Figs. 1 and 2). Measuring 16 ± 2.0 (13–18) μm × 10 ± 1.6 (8–12) μm with shape index of 1.5 (1.3–1.8) μm. Oocyst wall was thin smooth and yellowish green in color with conspicuous micropyle (Fig. 1). This wall is composed of two layers: an outer, very fine membrane and a thicker inner one (Fig. 1). Oocysts have a prominent oocyst residuum (Fig. 2). Each oocyst contained four dizoic sporocysts (Figs. 1 and 2). They were ovoid in shape and surrounded with smooth single-layer sporocyst wall (Fig. 1). These sporocysts measured 7 ± 0.6 (6–9) μm × 5 ± 0.4 (4–7) μm with shape index 1.4 (1.3–1.6) μm.

Figures 1–8.

(1, 2) Light micrographs of freshly shed sporulated oocysts of Eimeria perforans collected from naturally infecting domestic rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus. Oocyst has four sporocysts (SPC), oocyst residuum (OR), micropyle (MP) and surrounded by two membrane layers; outer layer (OL) and inner layer (IL). Scale-bar = 5 μm. (3) Mature meronts with mature merozoites (Me) in the parasitophorous vacuole (PV). Scale-bar = 10 μm. (4, 5) Developing microgamonts in bright parasitophorous vacuole (PV). Scale-bar = 10 μm. (6) Young macrogamonts with prominent nucleus and located in parasitophorous vacuole (PV). Scale-bar = 10 μm. (7) Developing macrogamonts with peripherally arranged wall-forming bodies (arrows) and prominent nucleus and located in parasitophorous vacuole (PV). Scale-bar = 10 μm. (8) Young oocyst (Oc) surrounded by the oocyst wall (OW) and located in parasitophorous vacuole (PV). Scale-bar = 10 μm.

5. Endogenous stages

Examinations of the stained duodenum sections showed presences of all developmental stages in the villi. Each developmental stage was observed within a bright parasitophorous vacuole. Mature meronts were nearly rounded and located within bright parasitophorous vacuole (Fig. 3). They measured 14 (12–16) μm in diameter estimated to produce 7–15 elongated merozoites. Mature microgamonts measured approximately 20 (18–21) × 16 (15–18) μm and were estimated to produce over 50 microgametes (Figs. 4 and 5). Young macrogamonts are ovoid to spherical, with a prominent nucleus (Fig. 6) and measuring 12 (10–14) × 9 (8–11) μm. With growth, a peripherally disposed ring of small wall-forming bodies was observed (Fig. 7). Young oocysts with differentiated zygotes were detected (Fig. 8).

6. Discussion

Coccidiosis is considered to be a major problem in rabbits as mortality rate may go high particularly during and after rainy season (Singla et al., 2000). Up to now, 15 eimerian species are known to infect rabbits (Li and Ooi, 2009). Many of them are highly pathogenic to their hosts causing great economic losses among the infected animals (Pakandl, 2009). Infections with a single Eimeria species are rare (Mehlhorn, 2006). For species diagnosis the oocyst is used as the most easily accessible stage in many coccidians (Mehlhorn, 2006; Bashtar et al., 2010). The available information on coccidian species infecting rabbits in Saudi Arabia is scarce and only nine species of Eimeria were identified (Kasim and Al-Shawa, 1987). The identification of these species was solely based on the exogenous stages regardless of the endogenous stage. In the present study, the exogenous and endogenous stages of E. perforans were recognized and described in naturally infected rabbits. This species could be differentiated easily based on size, shape, color, the presence of an oocyst residuum and micropyle and sporulation time. The morphology and measurements of E. perforans recorded in the present study are similar to those described by Kasim and Al-Shawa (1987) and Bashtar et al. (2003). In addition, our descriptions of the sporulated oocysts of E. perforans vary slightly in size and other minor characteristics from previous descriptions (Francalancia and Manfredini, 1967; Cheissin, 1968; Pellérdy, 1974; Norton et al., 1979; Hobss and Twigg, 1998; Razavi et al., 2010).

The sporulation time recorded in the present study was 24 h which is less than those mentioned by (Kvicerová et al., 2008). Decrease in the sporulation time may be due to crowdedness of oocysts or depends on contamination (Bashtar et al., 2010). This may also support the opinion that different sporulation times may be related to different experimental factors or laboratory techniques or to the lack of adequate oxygen (Long et al., 1976; Koudela and Vitovec, 1998; Abd Al-Aal, 2000; Bashtar et al., 2010). The natural prevalence of the infection recorded in the present study was 75% which is similar to those reported by Kasim and Al-Shawa (1987). Regarding the endogenous stages, it is not possible to determine the number of merogenic generations through natural infection. In general, the exact number of merogenic generations among the genus Eimeria is not fixed (Dai et al., 2005). After a specific number of merogonic generations, the merozoites develop into either microgamonts and/or macrogamonts (Hammond, 1973). Microgamonts with varying sizes and varying numbers of produced microgametes were reported for many species of Eimeria (Teixeira et al., 2004; Dai et al., 2005; Bashtar et al., 2010). Macrogamonts reported in this study characterized by the peripherally arranged wall-forming bodies. These results are in accordance with those reported for many other Eimeria species (Abdel-Ghaffar et al., 1991; Dai et al., 2005; Mehlhorn, 2006; Bashtar et al., 2010). After fertilization the wall-forming bodies fused together to form the double oocyst wall. Similar observations were reported by Mehlhorn (2006), Bashtar et al. (2010).

Acknowledgment

This work was gratefully supported by the Center of Excellence for Biodiversity Research, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

- Abd Al-Aal Z. Sexual stages and oocyst formation of Eimeria fayomensis Al-Hoot et al., 1988 (Apicomplexa, Eimeriidae): a light and transmission electron microscopic study. Egypt. J. Zool. 2000;35:373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Ghaffar, F.A., Bashtar, A.R., Mustafa, A.M., El Touky, A., 1991. Eimeria arvicanthi Van Den Berghe & Chardome, 1956 and E. mehlhorni nov. sp. infecting field rat Arvicanthus niloticus niloticus in Egypt. Arch Protistenkd. 140, 185-190.

- Al-Ghamdy A.A., Shazly M., AL-Rasheid K.A.S., Muborak M., Bashtar A. Light and electron microscopy of Eimeria magna Pérard, 1925 infecting the house rabbit, oryctolagus cuniculus from Saudi Arabia. II. gamogony and oocyst wall formation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2005;12:114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bashtar A., AL-Rasheid K.A.S., Mobarak M., Al-Ghamdy A.A. Coccidiosis in rabbits from Saudi Arabia. 1- Exogenous stages of different Eimeria spp. J. Egypt. Ger. Soc. Zool. 2003;42D:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bashtar A., Abdel-Ghaffar F., AL-Rasheid K.A.S., Mehlhorn H., Al Nasr I. Light microscopic study on Eimeria species infecting Japanese quails reared in Saudi Arabian farms. Parasitol. Res. 2010;107:409–416. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1881-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceré N., Humbert J.F., Licois D., Corvione M., Afanassieff M., Chanteloup N. A new approach for the identification and the diagnosis of Eimeria media parasite of the rabbit. Exp. Parasitol. 1996;82:132–138. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheissin E.M. On the distinctness of the species Eimeria neoleporis Carvalho, 1942 from the cottontail rabbit Sylvilagus floridanus mearnsii and Eimeria coecicola Cheissin, 1947 from 396 the tame rabbit. Acta Protozool. 1968;6:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Coudert, P., 1989. Some peculiarities of rabbit coccidiosis. In: Yvore, P. (Ed.), Coccidia and Intestinal Coccidiomorphs, Proceedings of the fifth International Coccidiosis Conference, Tours, France, October 17–20.

- Dai Y., Liu X., Lju M., Tao J. The life cycle and pathogenicity of coccidium Eimeria nocens (Kotlan, 1933) in domestic goslings. J. Parasitol. 2005;91:1122–1125. doi: 10.1645/GE-476R1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francalancia G., Manfredini L. Diagnosis of species of the rabbit coccidiosis (Eimeria) Vet. Ital. 1967;18:304–310. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D.M. Life cycles and development of Eimeria, Isos pora, Toxoplasma and related genera. In: Long P.L., editor. University Park Press; Baltimore: 1973. pp. 45–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hobss R.P., Twigg L.E. Coccidia (Eimeria spp.) of wild rabbits in southwestern Australia. Aust. Vet. J. 1998;76:209–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1998.tb10131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasim A.A., Al-Shawa Y.R. Coccidia in rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Parasitol. 1987;17:941–944. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(87)90012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koudela B., Vitovec J. Biology and pathogenicity of Eimeria neodebliecki Vetterling, 1965 in experimentally infected pigs. Parasitol. Inter. 1998;47:249–256. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(92)90014-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvičerová J., Pakandl M., Hypša V. Phylogenetic relationships among Eimeria spp. (Apicomplexa, Eimeriidae) infecting rabbits: evolutionary significance of biological and morphological features. Parasitology. 2008;135:443–452. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007004106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Ooi H. Fecal occult blood manifestation of intestinal Eimeria spp. infection in rabbit. Vet. Parasitol. 2009;161:327–329. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licois D., Coudert P. Coccidioses et diarrhées du lapin a‘ l’engraissement. Bull. GTV. 1982;5:109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Long P.L., Joyner L.P., Millard B.J., Norton C. A guide to laboratory techniques used in the study and diagnosis of avian coccidiosis. FoliaVet. 1976;6:201–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlhorn H. Morphology. In: Mehlhorn H., editor. Parasitology in Focus, Facts and Trends. third ed. Springer; Berlin: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Norton C.C., Catchpole J., Joyner L.P. Redescriptions of Eimeria irresidua Kessel and Jankiewicz 1931 and Eimeria flavescens Marotel and Guilhon 1941 from the domestic rabbit. Parasitology. 1979;79:231–248. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000053312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakandl M. Coccidia of rabbit: a review. Folia Parasitol. 2009;56:153–166. doi: 10.14411/fp.2009.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellérdy, L., 1974. Coccidia and Coccidiosis, second ed. Paul Parey, Berlin and Hamburg, Germany, p. 959.

- Razavi S.M., Oryan A., Rakhshandehroo E., Moshiri A., Mootabi Alavi A. Eimeria species in wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Fars province. Iran Trop. Biomed. 2010;27:470–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtyseck E., Hammond D.M., Ernst J.V. Fine structure of the macrogametes of Eimeria perforans, E. stiedae, E. bovis, and E. auburnensis. J. Parasitol. 1966;52:975–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shazly M., Muborak M., AL-Rasheid K.A.S., Al-Ghamdy A.A., Bashtar A. Light and electron microscopy of eimeria magna infecting the house rabbit, oryctolagus cuniculus from Saudi Arabia. I. Asexual developmental cycles. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2005;12:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Singla L.D., Juyal P.D., Sandhu B.S. Pathology and therapy in naturally Eimeria stiedae-infected rabbits. J. Protozool. Res. 2000;10:185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira M., Teixeira F.W.L., Lopes C.W.G. Coccidiosis in Japanese quails (Coturnix japonica): characterization of a naturally occurring infection in a commercial rearing farm. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Avic. 2004;6:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Toula F.H., Ramadan H.H. Studies on coccidian species of Genus Eimeria from domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus domesticus L.) in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 1998;28:691–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]