Abstract

The bio-efficacy of Aloe vera leaf extract and bacterial insecticide, Bacillus sphaericus larvicidal activity was assessed against the first to fourth instars larvae of Aedes aegypti, under the laboratory conditions. The plant material was shade dried at room temperature and powdered coarsely. A. vera and B. sphaericus show varied degrees of larvicidal activity against various instars larvae of A. aegypti. The LC50 of A. vera against the first to fourth instars larvae were 162.74, 201.43, 253.30 and 300.05 ppm and the LC90 442.98, 518.86, 563.18 and 612.96 ppm, respectively. B. sphaericus against the first to fourth instars larvae the LC50 values were 68.21, 79.13, 93.48, and 107.05 ppm and the LC90 values 149.15, 164.67, 183.84, and 201.09 ppm, respectively. However, the combined treatment of A. vera + B. sphaericus (1:2) material shows highest larvicidal activity of the LC50 values 54.80, 63.11, 74.66 and 95.10 ppm; The LC90 values of 145.29, 160.14, 179.74 and 209.98 ppm, against A. aegypti in all the tested concentrations than the individuals and clearly established that there is a substantial amount of synergist act. The present investigation clearly exhibits that both A. vera and B. sphaericus materials could serve as a potential larvicidal agent. Since, A. aegypti is a container breeder vector mosquito this user and eco-friendly and low-cost vector control strategy could be a viable solution to the existing dengue disease burden. Therefore, this study provides first report on the mosquito larvicidal activity the combined effect of A. vera leaf extract and B. sphaericus against as target species of A. aegypti.

Keywords: Aloe vera, Bacillus sphaericus, Aedes aegypti, Dengue vector, Larvicidal activity

1. Introduction

A recent estimate shows that more than 50 million people are at risk of dengue virus exposure worldwide. Annually, there are 2 million infections, 500,000 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever, and 12,000 deaths (Guha-Sapir and Schimme, 2005). Aedes aegypti is generally known as a vector for an arbo-virus responsible for dengue fever, which is endemic to Southeast Asia, the Pacific island area, Africa, and the Americas. This mosquito also acts as a vector of yellow fever in Central and South America and West Africa. However, Dengue fever has become an important public health problem as the number of reported cases continues to increase, especially with more severe forms of the disease, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome, or with unusual manifestations such as central nervous system involvement (Pancharoen et al., 2002).

A. aegypti is a cosmotropical species that proliferates in water containers in and around houses. Secondary vectors include Aedes albopictus, an important vector in Southeast Asia and that has spread to the Americas, western Africa and the Mediterranean rim, Aedes mediovittatus in the Caribbean, and Aedes polynesiensis and Aedes scutellaris in the western Pacific region. A. aegypti breeds in many types of household containers, such as water storage jars, drums, tanks, and plant or flower containers (Muir and Kay, 1998; Honorio et al., 2003; Harrington et al., 2005; Murugan et al., 2011).

Mosquito control, in view of their medical importance, assumes global importance. In the context of ever increasing trend to use more powerful synthetic insecticides to achieve immediate results in the control of mosquitoes, an alarming increase of physiological resistance in the vectors, its increased toxicity to non-target organism and high costs are noteworthy (WHO, 1975). Most of synthetic chemicals are expensive and destructive to the environment and also toxic to humans, animals and other non-target organisms. Besides, they are non-selective and harmful to other beneficial organisms. Some of the insecticides act as carcinogenic agents and are even carried through food chain which in turn affects the non-target organism. Therefore alternative vector control strategies, especially effective and low cost are extremely imperative (Piyarat et al., 1974; Kalyanasundaram and Das, 1985).

The use of different parts of locally available plants and their various products in the control of mosquitoes has been well established globally by numerous researchers. The larvicidal properties of indigenous plants have also been documented in many parts of India along with the repellent and anti-juvenile hormones activities (Singh and Bansal, 2003). Almost all tropical regions of the world are experiencing the resurgence and reoccurrence of one of the world’s most deadly diseases, i.e., malaria, filariasis, dengue, and Chikungunya in world and India is no exception. Traditionally, plants and their derivatives were used to kill mosquitoes and other household and agricultural pests. In all probability, these plants used to control insects contained insecticidal phytochemicals that were predominantly secondary compounds produced by plants to protect themselves against herbivorous insects (Shaalan et al., 2005; Preeti Sharma et al., 2009).

Aloe vera is a perennial plant belonging to the family of Liliaceae, of which there are about 360 species (Klein and Penneys, 1988). Taxonomists now refer to Aloe barbadensis as A. vera (Coats and Ahola, 1979). Aloe is one of the few medicinal plants that maintain its popularity for a long period of time. The plant has stiff, graygreen lance-shaped leaves containing clear gel in a central mucilaginous pulp. A. vera gel has hypoglycemic (Rajasekaran et al., 2004), wound healing (Pandarinathan et al., 1998) and anti-inflammatory effects (Davis et al., 1991). The A. vera (L.) Burm. f., plant (synonym = Aloe barbadensis Miller) is commonly referred to as A. vera and belongs to the lily family (family: Liliaceae, tribe Aloinae). This species is one of the approximately 420 species of aloe (Burdock, 1997).

Since, 1986 A. vera has been used as a traditional medicine and as an ingredient in many cosmetic products; it has gained high importance for its diverse therapeutic properties. The plant, being succulent, contains 99.5% water and the remaining solid material contains over 75 different ingredients including vitamins, minerals, enzymes, sugars, anthraquinones or phenolic compounds, lignin, tannic acids, polysaccharide, glycoproteins, saponins, sterols, amino acids, and salicylic (Reynolds and Dweck, 1999). A. vera provides nutrition, shows anti-inflammatory action and has a wide range of antimicrobial activity (Reynolds and Dweck, 1999).

Bacillus sphaericus is a naturally occurring soil bacterium that can effectively kill mosquito larvae present in water. B. sphaericus has the unique property of being able to control mosquito larvae in water that is rich in organic matter. B. sphaericus is effective against Culex spp. but is less effective against some other mosquito species. Commercially available formulations of B. sphaericus are sold under the trade name Vectolex. When community mosquito control is needed to reduce mosquito-borne disease, the Department of Health favors the use of larvicide applications targeted to the breeding source of mosquitoes (Meisch, 1990).

Bacterial larvicides have been used for the control of nuisance and vector mosquitoes for more than two decades. The discovery of bacterium like B. sphaericus, which is highly toxic to dipteran larvae, has opened the possibility of its use as a potential biolarvicide in mosquito eradication program worldwide (Kalfon et al., 1984). The mosquitocidal activity of the highly active strain of B. sphaericus resulted in their development as commercial larvicides. This is now used in many countries in various parts of the world to control vector and nuisance mosquito species (Wirth et al., 2001).

Indeed, source reduction is one of the key components in the malaria vector control program since the target is exceptionally specific unlike adult control. Innovative vector control strategy like use of phytochemicals as alternative sources of insecticidal/larvicidal agents in the fight against the vector-borne diseases has become inevitable. Above and beyond, in recent epoch, around the globe phytochemicals have gained massive attention by various researchers because of their bio-degradable and eco-friendly values (Karunamoorthi and Ilango, 2010). In this context, the purpose of the present investigation is to explore the larvicidal properties of A. vera leaf extract and bacterial insecticide, B. sphaericus against Chikungunya vector, A. aegypti, under the laboratory conditions. Therefore, this study provides first report on the mosquito larvicidal activity combined effect of A. vera leaf extract and B. sphaericus against A. aegypti as target species.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Collection of eggs and maintenance of larvae

The eggs of A. aegypti were collected from National Centre for Disease Control field station of Mettupalayam, Tamil Nadu, India, using an “O”-type brush. These eggs were brought to the laboratory and transferred to 18 × 13 × 4-cm enamel trays containing 500 mL of water for hatching. The mosquito larvae were fed pedigree dog biscuits and yeast at 3:1 ratio. The feeding was continued until the larvae transformed into the pupal stage.

2.2. Maintenance of pupae and adults

The pupae were collected from the culture trays and transferred to plastic containers (12 × 12 cm) containing 500-mL of water with the help of a dipper. The plastic jars were kept in a 90 × 90 × 90-cm mosquito cage for adult emergence. Mosquito larvae were maintained at 27 ± 2 °C, 75–85% relative humidity, under a photoperiod of 14:10 (light/dark). A 10% sugar solution was provided for a period of 3 days before blood feeding.

2.3. Blood feeding of adult A. aegypti

The adult female mosquitoes were allowed to feed on the blood of a rabbit (a rabbit per day, exposed on the dorsal side) for 2 days, to ensure adequate blood feeding for 5 days. After blood feeding, enamel trays with water from the culture trays were placed in the cage as oviposition substrates.

2.4. Collection of plant and preparation of extract

A. vera was collected in and around Bharathiar University Campus, Coimbatore, India. The voucher specimen has been deposited and kept in our research laboratory for further reference. A. vera plant was washed with tap water and shade dried at room temperature. An electrical blender powdered the dried plant materials (leaves). From the powder, 300 g of the plant materials was extracted with 1 L of organic solvents of petroleum ether for 8 h using a Soxhlet apparatus (Vogel, 1978). The extracts were filtered through a Buchner funnel with Whatman number 1 filter paper. The crude plant extracts were evaporated to dryness in a rotary vacuum evaporator. One gram of the plant residue was dissolved in 100 mL of acetone (stock solution) and considered as 1% stock solution. From this stock solution, different concentrations were prepared ranging from 80, 160, 240, 320 and 400 ppm, respectively.

2.5. Microbial bioassay

B. sphaericus was obtained from T. Stanes & Company Limited, Research and Development Centre, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India. The organism was grown in a liquid medium containing (in grams per liter of distilled water): FeSO4·7H2O, 0.01; MnSO4, 0.1; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.2; CaCl2, 0.08; K2HPO4, 0.025; yeast extract, 2; peptone, 4; and d-glucose, 1 and casein, 5. Solutions of yeast extract, peptone casein, d-glucose, K2HPO4 and CaCl2 were separately prepared, sterilized, and added before inoculation. The pH of the medium was adjusted to 7.1 before sterilization. The required quantity of B. sphaericus was thoroughly mixed with distilled water and prepared at various concentrations ranging from 25, 50, 75, 100 and 125 ppm, respectively.

2.6. Larval toxicity test

A laboratory reared colony of A. aegypti larvae was used for the larvicidal activity. Twenty-five individuals of first, second, third, and fourth instars larvae were kept in a 500 mL glass beaker containing 249 mL of dechlorinated water and 1-mL of desired concentration of A. vera leaf extracts and B. sphaericus were added. Larval food was given for the test larvae. At each tested concentration, two to five trials were made and each trial consists of five replicates. The control was setup by mixing 1 mL of acetone with 249 mL of dechlorinated water. The larvae exposed to decholorinated water without acetone served as control. The control mortalities were corrected by using Abbott’s formula (Abbott, 1925).

The LC50 and LC90 were calculated from toxicity data by using probit analysis (Finney, 1971).

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data were subjected to analysis of variance; the means were separated using Duncan’s multiple range tests by Alder and Rossler (1977). The average larval mortality data were subjected to probit analysis, for calculating LC50 and LC90, values were calculated by using the Finney (1971) method. SPSS (Statistical software package) 9.0 version was used. Results with P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

Larval mortality of A. aegypti after the treatment of petroleum ether A. vera was observed. Table 1 provides the results of larval mortality of A. aegypti (I–IV instars) after the treatment of A. aegypti at different concentrations (80–400 ppm). Thirty-four percent mortality was noted at I instar larvae by the treatment of A. vera at 80 ppm, whereas it has been increased to 89% at 400 ppm of A. vera leaf extract treatment. Similar trend has been noted for all the instars of A. aegypti at different concentrations of A. vera treatment. The LC50 and LC90 values were represented as follows; LC50 value of I instar was 162.74 ppm, II instar was 201.43 ppm, III instar was 253.30 ppm, and IV instar was 300.05 ppm, respectively. The LC90 value of I instar was 442.98 ppm, II instar was 518.86 ppm, III instar was 563.18 ppm and IV instar was 612.96 ppm, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Larvicidal activity of A. vera leaf extract against A. aegypti.

| Mosquito larval instars | % of larval mortality | LC50 (LC90) | 95% confidence limit |

χ2 (df = 4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration of AVLE (ppm) |

LFL | UFL | |||||||

| 80 | 160 | 240 | 320 | 400 | LC50 (LC90) | LC50 (LC90) | |||

| I | 34a | 53a | 64a | 71a | 89a | 162.74 (442.98) | 128.19 (395.17) | 189.79 (516.81) | 2.87⁎ |

| II | 29ab | 48b | 56b | 64b | 81b | 201.43 (518.86) | 168.33 (455.12) | 229.81 (623.39) | 2.27⁎ |

| III | 24bc | 36c | 47c | 58c | 75c | 253.30 (563.18) | 225.36 (493.94) | 282.81 (675.91) | 0.66⁎ |

| IV | 19c | 28d | 41d | 50d | 68d | 300.059 (612.96) | 271.32 (534.46) | 336.01 (742.76) | 0.67⁎ |

Control – nil mortality, LFL – lower fiducidal limit, UFL – upper fiducidal limit, χ2 – Chi-square value, df – degrees of freedom.

Within a column means followed by the same letter(s) are not significantly different at 5% level by DMRT. Each value is five replicates.

Significant at P < 0.05 level.

Figure 1.

Larvicidal activity of A. vera leaf extract against A. aegypti expressed as LC50 and LC90.

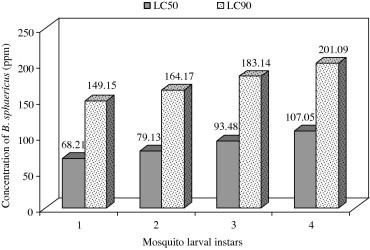

Table 2 shows the results of larval mortality of A. aegypti (I–IV instars) after the treatment of B. sphaericus at different concentrations (25–125 ppm). Twenty-seven percent mortality was noted at I instar larvae by the treatment of B. sphaericus at 25 ppm, whereas it has been increased to 85% at 125 ppm of B. sphaericus treatment and 12% mortality was noted at pupae by the treatment of B. sphaericus at 25 ppm and it has been increased to 60% at 125 ppm. Similar trend has been noted for all the instars of A. aegypti at different concentrations of B. sphaericus treatment. The LC50 and LC90 values were represented as follows: LC50 value of I instar was 68.21 ppm, II instar was 79.13 ppm, III instar was 93.48 ppm, and IV instar was 107.05812 ppm, respectively. The LC90 value of I instar was 149.15 ppm, II instar was 164.67 ppm, III instar was 183.84 ppm, and IV instar was 201.09 ppm, respectively (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Larvicidal activity of bacterial insecticide, B. sphaericus against A. aegypti.

| Mosquito larval instars | % of larval mortality | LC50 (LC90) | 95% confidence limit |

χ2 (df = 4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration of B. sphaericus (ppm) |

LFL | UFL | |||||||

| 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 125 | LC50 (LC90) | LC50 (LC90) | |||

| I | 27a | 39a | 50a | 67a | 85a | 68.21 (149.2) |

60.35 (134) |

75.58 (171.8) |

2.05⁎ |

| II | 21ab | 35b | 46a | 59b | 78b | 79.13 (164.7) |

71.36 (146.8) |

87.28 (192.2) |

1.07⁎ |

| III | 16bc | 28c | 41ab | 50c | 69c | 93.48 (183.8) |

85.12 (162.1) |

103.71 (218.6) |

0.84⁎ |

| IV | 12c | 23d | 35b | 44d | 60d | 107.05 (201.1) |

97.36 (175.3) |

120.48 (243.7) |

0.55⁎ |

Control-Nil mortality, LFL – lower fiducidal limit, UFL – upper fiducidal limit, x2 – Chi-square value, df – degrees of freedom.

Within a column means followed by the same letter(s) are not significantly different at 5% level by DMRT. Each value is five replicates.

Significant at P < 0.05 level.

Figure 2.

Larvicidal activity of B. sphaericus against A. aegypti expressed as LC50 and LC90.

The considerable larval mortality after the combined effect of B. sphaericus and A. vera extract against all the larval instars in A. aegypti is provided in (Table 3 and Fig. 3). The concentration at 20 + 10 ppm combined treatment of B. sphaericus and A. vera for I instar larval mortality was 41%. The LC50 and LC90 values were represented as follows: LC50 value of I instar was 54.80 ppm, II instar was 63.11 ppm, III instar was 74.66 ppm and IV instar was 95.10 ppm. The LC90 value of I instar was 145.29 ppm, II instar was 160.14, III instar was 179.74 ppm and IV instar was 209.98 ppm, respectively.

Table 3.

Combined treatment of larvicidal activity of A. vera leaf extract and bacterial insecticide, B. sphaericus against A. aegypti.

| Mosquito larval instars | % of larval mortality | LC50 (LC90) | 95% confidence limit |

χ2 (df = 4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration of AVLE (ppm) + B. sphaericus (ppm) |

LFL | UFL | |||||||

| 20 + 10 | 40 + 20 | 60 + 30 | 80 + 40 | 100 + 50 | LC50 (LC90) | LC50 (LC90) | |||

| I | 41a | 56a | 69a | 82a | 94a | 54.80 (145.29) | 41.63 (131.78) | 64.65 (165.23) | 4.73⁎ |

| II | 38a | 52a | 61b | 79ab | 90a | 63.11 (160.14) | 50.52 (144.29) | 72.79 (184.28) | 4.11⁎ |

| III | 33b | 45b | 57b | 74b | 83b | 74.66 (179.74) | 62.93 (160.35) | 84.30 (210.42) | 3.48⁎ |

| IV | 27c | 36c | 48c | 62c | 75c | 95.10 (209.98) | 84.57 (184.25) | 105.73 (252.87) | 3.16⁎ |

Control – nil mortality, LFL – lower fiducidal limit, UFL – upper fiducidal limit, χ2 – Chi-square value, df – degrees of freedom.

Within a column means followed by the same letter(s) are not significantly different at 5% level by DMRT. Each value is five replicates.

Significant at P < 0.05 level.

Figure 3.

Combined treatment of larval mortality of A. vera leaf extract and B. sphaericus against A. aegypti at 24 h.

4. Discussion

Mosquitoes in the larval stage are attractive targets for pesticides because mosquitoes breed in water, which makes it easy to deal with them in this habitat. The use of conventional pesticides in the water sources, however, introduces many risks to people and the environment. Natural pesticides, especially those derived from plants, are more promising in this aspect. Aromatic plants and their essential oils are very important sources of many compounds that are used in different respects (Amer and Mehlhorn, 2006a).

Recent studies on the larval and pupal mortality of Anopheles stephensi after the treatment of methanol extract of Clerodendron inerme leaf extract showed 22% mortality at I instar larvae as a result of treatment at 20 ppm; in contrast, it was increased to 81% at 100 ppm of C. inerme leaf extract of larval and pupal mortality of A. stephensi (I–IV instars) after the treatment of methanol extract of Acanthus ilicifolius at different concentrations (20–100 ppm). A 23% mortality was noted at I instar larvae by the treatment of A. ilicifolius at 20 ppm, whereas it was increased to 89% at 100 ppm of A. ilicifolius leaf extract treatment (Kovendan and Murugan, 2011).

The isolated compound saponin from ethyl acetate extract of Achyranthes aspera was effective against the larvae of A. aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus with LC50 value of 18.20 and 27.24 ppm, respectively (Bagavan et al., 2008). The neem formulation, Neem Azal, produced an overall mortality or inhibition of emergence of 90% (EI90, when third-instar larvae were treated) at 0.046, 0.208, and 0.866 ppm in A. stephensi, C. quinquefasciatus, and A. aegypti, respectively (Gunasekaran et al., 2009). Fraction A1 of ethanol from Sterculia guttata seed extract was found to be most promising; its LC50 was 21.552 and 35.520 ppm against C. quinquefasciatus and A. aegypti, respectively (Katade et al., 2006a,b). With A. barbadensis the larvicidal activity increases with increase in the exposure period from 24 to 48 h with decrease in LC50 values from 15.31 to 11.01 ppm (carbon tetrachloride extract), 25.97 to 16.60 ppm (petroleum ether extract) and 144.44 to 108.38 ppm (methanol extract). Similar trend was also observed in case of Cannabis sativa with LC50 values 88.51 to 68.69 ppm (carbon tetrachloride extract), 294.42 to 73.32 ppm (petroleum ether extract) and 160.78 to 71.71 ppm (methanol extract) on increase in the exposure period. Further, Barnard and Rui De (2004) observed the repellent activity of A. vera against A. albopictus and Culex nigripalpus.

The leaf extract of Acalypha alnifolia with different solvents – hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, acetone, and methanol – were tested for larvicidal activity against three important mosquitoes such as malarial vector, A. stephensi, dengue vector, A. aegypti and Bancroftian filariasis vector, C. quinquefasciatus and highest larval and pupal mortality were found in the leaf extract of methanol Carica papaya against the first to fourth instar larvae and pupae of values LC50 = 51.76, 61.87, 74.07, 82.18 and 440.65 ppm, respectively (Kovendan et al., 2012b,c). In the present results, the LC50 and LC90 values of A. vera against first to fourth instars larvae were 162.74, 201.43, 253.30 and 300.05 ppm; the LC90 values of 442.98, 518.86, 563.18 and 612.96 ppm, respectively.

However, in our case, early detection of resistance against B. sphaericus could be better for the management of resistance development. Experts of resistance management have been involved in resistance detection with generations of mosquitoes. Moreover, the detection of resistance in an early stage could be a better approach to control mosquitoes. Laboratory- and field-collected C. quinquefasciatus exposed to B. sphaericus strain 2362 for 35 generations in the laboratory showed a level of resistance 43- and 12-fold than that of potential generation, respectively (Rodeharoen and Mulla, 1991). B. sphaericus, a spore-forming, entamopathogenic bacterium, has been shown to possess potent larvicidal activity against several species of mosquito larvae (Davidson, 1983; Yousten and Wallis, 1987). A flowable concentrate of B. sphaericus (Neide) strain 2362 was applied against Anopheles gambiae Giles s.l. mosquito larvae in small plot field trials in Bobo-Dioulasso area, Burkina-Faso. Third and fourth instar larvae were controlled for 10–15 days with a dosage of 10 g/m2, 3–10 days with 1 or 0.1 mg/m2, and 2 days with 0.01 g/m2 (Nicolas et al., 1987).

B. sphaericus showed a good control over A. stephensi which may be due to the presence of Bin and mosquitocidal toxins (Mtxs). As a consequence of the specific toxicity to mosquito larvae of Bin and Mtxs produced during the sporulation and vegetative stages, respectively, some toxic strains have been widely used for many years as bio-pesticides in the field of mosquito control programs (Bei et al., 2006). The soil bacterium showed varied mortality rate related to the larval stages and concentrations. The younger larval stages were much susceptible than the later ones. Active strains of B. sphaericus are known to produce considerable quantities of at least two sets of proteinaceous mosquito larvicidal factors at the onset of stationary phase (Souza et al., 1988; Baumann et al., 1991; Porter et al., 1993). Larvicidal activity was observed in all strains of B. sphaericus from Amazonia in differentiated toxicity levels (Eleiza de et al., 2008). In the present study, B. sphaericus treatment reduced the larvicidal properties of microbial insecticides development of growth control.

Singh and Prakash (2009) have reported that six different concentrations were used in laboratory bioassays (05, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg/l) for A. stephensi. Similarly, in the case of C. quinquefasciatus, six statistically significant different concentrations were used (0.01, 0.04, 0.05, 0.10, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/l) of B. sphaericus. It was recorded after exposure of 24 h. The percentages of mortalities were different for the different instars of C. quinquefasciatus and were used in laboratory bioassays (05, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg/l) for A. stephensi. Similarly, in the case of C. quinquefasciatus, six statistically significant different concentrations were used (0.01, 0.04, 0.05, 0.10, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/l) of B. sphaericus. It was recorded after exposure of 24 h. The percentages of mortalities were different for the different instars of C. quinquefasciatus and A. stephensi. Bioassay studies of B. sphaericus have been carried out in different parts of the world, including India, on mosquitoes in laboratories and fields (Rodrigues et al. 1998). B. sphaericus against the first to fourth instar larvae and pupae had the following values: I instar was 0.051%, II instar was 0.057%, III instar was 0.062%, IV instar was 0.066%, and for the pupae was 0.073%, respectively. B. sphaericus, an obligate aerobe bacterium, showed that it has good and effective mosquito control properties and also can act as an eco-friendly, biopesticide for further vector control programs. In a previous study, B. sphaericus, the bacterial pesticide was isolated from the soil samples and used to control the malarial vector, A. stephensi (Kovendan et al., 2012a). In the present results, the LC50 and LC90 values of B. sphearicus were 68.21, 79.13, 93.48, and 107.05 ppm; The LC90 values of 149.15 164.67, 183.84 and 201.09 ppm, respectively.

Vector control is one of the most powerful weapons in the process of managing vector populations to reduce/interrupt the transmission of disease. As a result, vector control remains considered to be a cornerstone in the vector-borne disease control program due to lack of reliable vaccine, drug resistance parasites and insecticide resistance of insect vectors disease (Karunamoorthi, 2011). In previous study, B. sphaericus and Leucas aspera first to fourth instars larvae and pupae against A. stephensi the LC50 and LC90 values were represented as follows: LC50 values of 2.03%, 2.04%, 2.05%, 2.05% and 2.07%; the LC90 values of 2.10%, 2.11%, 2.12%, 2.13% and 2.16%, respectively (Kovendan et al., 2012a). In the present results, the LC50 and LC90 values of A. vera leaf extract and B. sphaericus against first to fourth instars larvae were 54.80, 63.11, 74.66 and 95.10 ppm; the LC90 values of 145.29, 160.14, 179.74 and 209.98 ppm, respectively.

5. Conclusion

This result clearly reveals that both the leaf extract of A. vera and bio-control agent B. sphaericus could serve as a potential larvicidal agents against the dengue vector A. aegypti and they have demonstrated a synergist act too. This approach could not only improve the bio-efficacy of B. sphaericus but also substantially reduce the possibilities of physiological resistance development in mosquito population. Therefore, the present strategy should be promoted in the dengue vector control program. The mode of action and larvicidal efficiency of the A. vera extract under the field conditions should be scrutinized and determined. Besides, further investigation regarding the effect on non-target organism is extremely important and imperative in the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. K. Sasikala, Professor and Head, Department of Zoology, Bharathiar University for the laboratory facilities providing for this experiment. The authors are grateful to Mr. N. Muthukrishnan, Technician and Mr. A. Anbarasan, Lab Assistant, National Centre for Diseases Control (NCDC), Mettupalayam, Tamil Nadu for the helping mosquito sample collection and identified mosquito species of samples provided for the experiment work.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abbott W.S. A method of computing the effectiveness of insecticides. J. Ecol. Entomol. 1925;18:265–267. [Google Scholar]

- Alder H.L., Rossler E.B. Freeman; San Francisco: 1977. Introduction to Probability and Statistics. pp. 246. [Google Scholar]

- Amer A., Mehlhorn H. Larvicidal effects of various essential oils against Aedes, Anopheles, and Culex larvae (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol. Res. 2006;99:466–472. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagavan A., Rahuman A.A., Kamaraj C., Geetha K. Larvicidal activity of saponin from Achyranthes aspera against Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol. Res. 2008;103:223–229. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-0962-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard D.R., Rui De Xue. Laboratory evaluation of mosquito repellent against Aedes albopictus, Culex nigripalpus and Ochlerotatus triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) J. Med. Entomol. 2004;41:726–730. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P., Clark M.A., Baumann L., Broadwell A.H. Bacillus sphaericus as a mosquito pathogen: properties of the organism and its toxins. Microbiol. Rev. 1991;55:425–436. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.425-436.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bei H., Haizhou L., Xiaomin H., Zhiming Y. Preliminary characterization of a thermostable DNA polymerase I from a mesophilic Bacillus sphaericus strain C3–41. Arch. Microbiol. 2006;186:203–209. doi: 10.1007/s00203-006-0135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdock G.A. Encyclopedia of Food and Color Additives. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1997. Aloe, extract (Aloe spp.) pp. 105–106. (vol. I). [Google Scholar]

- Coats, Ahola R. Garland; Dallas: 1979. A Modern Study of Aloe vera. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E.W. Alkaline extraction of toxin from spores of the mosquito pathogen Bacillus sphaericus strain 1593. Can. J. Microbiol. 1983;29:271–275. doi: 10.1139/m83-044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H., Parker L., Samson T. The isolation of an active inhibitory system from an extract of Aloe vera. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 1991;81:258–261. doi: 10.7547/87507315-81-5-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleiza de C., Litaiff E., Wanderli P.T., Jorge I., Porto Ila R., De M., Aguiar O. Analysis of toxicity on Bacillus sphaericus from amazonian soils to Anopheles darlingi and Culex quinquefasciatus larvae. Acta Amaz. 2008;38(2):255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Finney D.J. Cambridge University Press; London: 1971. Probit Analysis. pp. 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Guha-Sapir D., Schimme B. Dengue fever: new paradigms for a changing epidemiology. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2005;12:13. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekaran K., Vijayakumar T., Kalyanasundaram M. Larvicidal and emergence inhibitory activities of NeemAzal T/S 1.2 per cent EC against vectors of malaria, filariasis and dengue. Indian J. Med. Res. 2009;130:138–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington L.C., Scott T.W., Lerdthusnee K., Coleman R.C., Costero A., Clark G.G., Jones J.J., Kitthawee S., Kittayapong P., Sithiprasasna R., Edman J.D. Dispersal of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti within and between rural communities, part 1. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005;72:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honorio N.A., Silva W.C., Leite P.J., Gonc alves J.M., Lounibosn L.P., Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Dispersal of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in an urban endemic dengue area in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:191–198. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalfon A., Charles J.F., Bourgouin C., de Barjac H. Sporulation of Bacillus sphaericus 2297: an electron microscope study of crystal like inclusion, biogenesis and toxicity to mosquito larvae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1984;130:893–900. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-4-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyanasundaram M., Das P.K. Larvicidal and synergistic activity of plant extracts for mosquito control. Indian J. Med. Res. 1985;82:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunamoorthi K. Vector control: a cornerstone in the malaria elimination campaign. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011;17:1608–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunamoorthi K., Ilango K. Larvicidal activity of Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf. and Croton macrostachyus Del. against Anopheles arabiensis Patton (Diptera: Culicidae), the principal malaria vector. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2010;14:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katade S.R., Pawar P.V., Wakharkar R.D., Deshpande N.R. Sterculia guttata seeds extractives—an effective mosquito larvicide. Ind. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;44:662–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katade S.R., Pawar P.V., Tungikar V.B., Tambe A.S., Kalal K.M., Wakharkar R.D., Deshpande N.R. Larvicidal activity of bis(2-ethyl-hexyl) benzene-1,2-dicarboxylate from Sterculia guttata seeds against two mosquito species. Chem. Biodiversity. 2006;3:49–53. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200690006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D., Penneys N. Aloe vera. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1988;18:714–720. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovendan K., Murugan K. Effect of medicinal plants on the mosquito vectors from the different agro-climatic regions of Tamil Nadu, India. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2011;5:335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Kovendan K., Murugan K., Vincent S., Barnard D.R. Studies on larvicidal and pupicidal activity of Leucas aspera Willd. (Lamiaceae) and bacterial insecticide, Bacillus sphaericus against malarial vector, Anopheles stephensi Liston. (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol. Res. 2012;110:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovendan K., Murugan K., Vincent S. Evaluation of larvicidal activity of Acalypha alnifolia Klein ex Willd. (Euphorbiaceae) leaf extract against the malarial vector, Anopheles stephensi, dengue vector, Aedes aegypti and Bancroftian filariasis vector, Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol. Res. 2012;110:571–581. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2525-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovendan K., Murugan K., Naresh Kumar A., Vincent S., Hwang J.S. Bio-efficacy of larvicidal and pupicidal properties of Carica papaya (Caricaceae) leaf extract and bacterial insecticide, spinosad against Chikungunya vector, Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol. Res. 2012;110:669–678. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2540-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisch M.V. Evaluation of Bacillus sphaericus against Culex quinquefasciatus in septic ditches. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1990;6:496–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir L.E., Kay B.H. Aedes aegypti survival and dispersal estimated by mark-release-recapture in northern Australia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1998;58:277–282. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan K., Hwang J.S., Kovendan K., Prasanna Kumar K., Vasugi C., Naresh Kumar A. Use of plant products and copepods for control of the dengue vector, Aedes aegypti. Hydrobiologia. 2011;666:331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas L., Darriet F., Hougard J.M. Efficacy of Bacillus sphaericus 2362 against larvae of Anopheles gambiae under laboratory and field conditions in West Africa. Med. Vet. Entomol. 1987;1(2):157–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1987.tb00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancharoen C., Kulwichit W., Tantawichien T., Thisyakorn U., Thisyakorn C. Dengue infection: a global concern. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2002;85:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandarinathan C.B., Sajithlal G.B., Gowri C. Influence of Aloe vera on collagen turn over in healing of dermal wounds in rats. Ind. J. Exp. Biol. 1998;36:896–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piyarat S.W.K., Freed M., Roy S. Biologically active plant extract for the control of mosquito larvae. Mosq. News. 1974;34:398. [Google Scholar]

- Porter A.G., Davidson E.W., Liu J.W. Mosquitocidal toxins of bacilli and their genetic manipulation for effective biological control of mosquitoes. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;57:838–861. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.838-861.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran S., Sivagnanam K., Ravi K., Subramanian S. Hypoglycemic effect of Aloe vera gel on streptozotocin-induced diabetes in experimental rats. J. Med. Food. 2004;7:61–66. doi: 10.1089/109662004322984725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds T., Dweck A.C. Aloe vera leaf gel: a review update. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999;68:3–37. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodeharoen J., Mulla M.S. University of California Riverside; 1991. Resistance in Culex quinquefasciatus to Bacillus sphaericus: An Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues I.B., Tadei W.P., Dias J.M.C.S. Studies on the Bacillus sphaericus larvicidal activity against malaria vector species in Amazonia. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 1998;93:441–444. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761998000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaalan E., Canyon D., Faried M.W., Abdel-Wahab H., Mansour A. A review of botanical phytochemicals with mosquitocidal potential. Environ. Int. 2005;31:1149–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P., Mohan L., Srivastava C.N. Amaranthus oleracea and Euphorbia hirta: natural potential larvicidal agents against the urban Indian malaria vector, Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol Res. 2009;106:171–176. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1644-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G., Prakash S. Efficacy of Bacillus sphaericus against larvae of malaria and filarial vectors: an analysis of early resistance detection. Parasitol. Res. 2009;104:763–766. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K.V., Bansal S.K. Larvicidal properties of a perennial herb Solanum xanthocarpum against vectors of malaria and dengue/DHF. Curr. Sci. 2003;84:749–751. [Google Scholar]

- Souza A.E., Rajan V., Jayaraman K. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of two DNA fragments from Bacillus sphaericus encoding mosquito-larvicidal activity. J. Biotechnol. 1988;7:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel A.I. The English Language Book Society and Longman; London: 1978. Textbook of Practical Organic Chemistry. pp. 1368. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, M.C., Yang, Y., Walton, W.E., Federici, B.A., 2001. Evaluation of alternative resistance management strategies for Bacillus sphaericus. Mosquito Control Research, Annual Report. Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California.

- World Health Organization, 1975. Manual on Practical Entomology in Malaria Part I. Who division of malaria and other parasitic diseases, pp. 160.

- Yousten A.A., Wallis D.A. Batch and continuous culture production of the mosquito larval toxin of Bacillus sphaericus 2362. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1987;2:277–283. [Google Scholar]