Abstract

Migraine cannot be cured and the aim, shared with the patient, is to minimise the impact of the illness on the patient’s life and lifestyle. The aim of prophylaxis is to reduce the number of migraine attacks. Prophylaxis should be considered when appropriately used acute management gives inadequate control of symptoms. The efficacy and safety of topiramate 50 mg/d and thioctic acid (α-lipoic acid) 300 mg/d either as monotherapy or in combination were investigated as migraine prophylactic agents. Forty secondary school migraineur girls were enrolled in the study. The study was conducted in two phases, a prospective baseline phase and 1-month treatment phase. Combined topiramate/thioctic acid therapy was more effective than either topiramate or thioctic acid monotherapy as a migraine-preventive treatment. Combined topiramate/thioctic acid therapy decreased the mean monthly migraine frequency from 5.86 ± 1.2 to 2.6 ± 0.98 (p ⩽ 0.05), topiramate (50 mg/d) from 5.71 ± 1.4 to 4.75 ± 1.5 and thioctic acid (300 mg/d) from 5.68 ± 1.6 to 5.22 ± 1.8. Reduction in mean monthly migraine days was also significantly greater in the group receiving combined topiramate/thioctic acid (from 12.32 ± 1.85 to 5.74 ± 1.1) compared to those receiving either topiramate 50 mg/d (from 12.7 ± 1.34 to 11.85 ± 1.35) or thioctic acid 300 mg/d (from 12.5 ± 1.72 to 11.65 ± 1.44). The responder rate (% of patients showing ⩾50% reduction in monthly migraine frequency) was 85% in patients receiving combined topiramate/thioctic acid therapy compared to 30% and 20% in patients receiving either topiramate or thioctic acid, respectively. The incidence of adverse events was higher in patients receiving topiramate (50 mg/d) monotherapy. The most common adverse events were nausea, fatigue, paraesthesia and taste perversion. We conclude that combined topiramate/thioctic acid therapy is more effective and better tolerated than topiramate monotherapy. The combination has lower monthly medication costs compared to the traditionally used topiramate 100 mg monotherapy.

Keywords: Topiramate, Thioctic acid, Migraine

1. Introduction

Migraine is a recurrent headache disorder with intense pain that may be unilateral and accompanied by nausea or vomiting as well as photosensitivity and phonosensitivity. The incidence of migraine headache is claimed to be 25% in women and 8% in men. Migraine also affects about 5–10% of children and adolescents (Carolyn et al., 2009). Approximately 53% of patients with severe migraine report that their attacks require bed rest or are a source of severe impairment (Lipton et al., 2001). The cost of missed workdays and impaired performance because of migraine is estimated at $18 billions (Silberstein et al., 2002) in the USA.

The exact cause of migraine headache is still unknown. Current research suggests that inflammation in the blood vessels of the brain causes them to swell and press on nearby nerves, causing pain (Salomone et al., 2009). This inflammation may arise in or be stimulated by signals from the trigeminal nerve, the main sensory nerve of the face (Debruyne and Herroelen, 2009). The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of migraine was supported by the findings of various studies. A significant increase in plasma levels of thiobarbituric acid reacting substances (TBARS) has been reported in migraineurs (Tozzi-Ciancarelli et al., 1997; Tuncel et al., 2008). Changes in platelet superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity have been reported in patients having migraine with aura (Shimomura et al., 1994). One study has reported a significant increase in urinary nitric oxide metabolites and lipid peroxidation by-products in migraineurs (Cinancarelli et al., 2003). Significant reductions in erythrocytic glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) and SOD activities have been reported in migraineurs with and without aura (Bolayir et al., 2004).

The United States Headache Consortium recommends preventive treatment when the following occurs: (a) migraine significantly interferes with daily routine, despite acute treatment; (b) acute medications fail, are contraindicated or lead to troublesome adverse events; (c) acute medications are overused; (d) there are circumstances, such as hemiplegic migraine or risk of permanent neurologic injury; (e) the patient experiences frequent headache attacks (>2 per week); or (f) the patient prefers preventive treatment (Silberstein, 2000). Effective preventive migraine treatments include antiepileptic drugs (Vikelis and Rapoport, 2010), antidepressants (Nagata, 2009; Koch and Jürgens, 2009), β-adrenoceptor blockers (Evers et al., 2006, 2009), calcium channel blockers (Negoro, 2009), botulinum toxin (Taylor, 2008; Mathew and Jaffri, 2009) and surgery (Guyuron et al., 2009). The antiepileptic drug “topiramate” is approved for the prophylaxis of migraine headache in adults. Topiramate, at doses of 100 and 200 mg/d (but not 50 mg/d), had been reported to be effective as a migraine-preventive therapy (Silberstein et al., 2004). Thioctic (α-lipoic) acid is both water- and fat-soluble antioxidant that is directly (by removing reactive species) and indirectly (by chelating transition metal ions) involved in the protection of biological components from the damage of oxidative stress (Haenen and Bast, 1991; Coon et al., 2003; Packer et al., 1996; Cronan et al., 2005). The use of thioctic acid in migraine prevention has been reported by some investigators (Sun-Edelstein and Mauskop, 2009). This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of topiramate 50 mg/d, thioctic acid 300 mg/d or a combination of both in migraine prophylaxis. The Egyptian MOH registration number for Topamax® is 21628. The MOH registration number for Thiotacid is 20943. Topamax® is indicated for migraine prophylaxis and as initial monotherapy in patients 10 years of age and older with partial onset or primary generalized tonic–clonic seizures. Thiotacid is indicated for the treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy, neuritis, poly-neuritis, optic neuritis and encephalopathies.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

The study subjects were entered into a prospective 1-month baseline phase and headache records were reviewed. Baseline phase completers who met the study criteria were randomized to either topiramate 50 mg/d, thioctic acid 300 mg/d or a combination of both. Topiramate dose was titrated by 25 mg/week to the assigned dose. During the maintenance period, topiramate 50 mg was given in two divided doses (morning and evening), while thioctic acid 300 mg was given on a once daily basis in the morning. All treatments were continued for 1 month.

During the treatment period, school clinic visits were planned weekly. Headache, medication and adverse reaction records were collected and analyzed and new records were dispensed. To ensure better compliance, the study medications were refilled freely every week (7 doses per regimen). Subjects were allowed to take acute migraine mediations (including aspirin, paracetamol, NSAIDs, triptans and ergot derivatives) recording the name and amount of the medication used.

2.1.1. Patients

Forty secondary school girls with ⩾3-month International Headache Society (IHS) migraine history were enrolled in this randomized open-label efficacy study. Patients were randomized to either topiramate 50 mg/d, thioctic acid 300 mg/d or a combination of both. All drug regimens were continued for 1 month.

2.1.2. Setting

Out-patient treatment at secondary school Health Insurance Clinics, Cairo, Egypt.

2.1.3. Inclusion criteria

Secondary school girl migraineurs aged 16–20 years experienced 5–11 migraines and 10–14 migraine days during the prospective 1-month baseline phase. All patients should fulfil the IHS diagnostic criteria for migraine headache (International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee, 2000).

2.1.4. Exclusion criteria

Patients with headaches other than migraine, previous treatment with any migraine prophylactic agent in the preceding 3 months, daily use of NSAIDs or corticosteroids and previous treatment with any of the test drugs in the preceding 3 months.

2.1.5. Study drugs

Topiramate (Topamax®), Janssen-Cilag, thioctic acid (Thiotacid), EvaPharma, Egypt.

2.2. Efficacy measures

Reduction in mean monthly migraine frequency and mean monthly migraine days from baseline was determined for the study groups. Patients were directed to record the start and end of migraine attacks. Migraine frequency was assessed by counting migraine headache that started, terminated or reappeared within 24 h. If the attack is continued for longer than 24 h, it was counted as a new migraine attack. The responder rate (⩾50% reduction in monthly migraine frequency) or percentage of migraineurs responding to treatment was also determined.

2.3. Safety measures

Safety was assessed by the incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and clinical examination. Clinical examination and ADRs were evaluated at weekly intervals.

2.4. Data analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. A paired student t-test was used to determine the difference between means of the same group at baseline and after drug therapy. The level of significance was set at p ⩽ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Efficacy measures

The mean change from baseline in monthly migraine frequency (Table 1 and Fig. 1) was significantly greater for patients receiving combined topiramate/thioctic acid therapy (group 3) but not for those receiving either topiramate 50 mg/d or thioctic acid 300 mg/d monotherapies (groups 1 and 2, respectively). Combined topiramate/thioctic acid therapy decreased the mean monthly migraine frequency from 5.86 ± 1.2 to 2.6 ± 0.98 (p ⩽ 0.05), topiramate (50 mg/d) from 5.71 ± 1.4 to 4.75 ± 1.5 and thioctic acid (300 mg/d) from 5.68 ± 1.6 to 5.22 ± 1.8.

Table 1.

Demographic, baseline, and post-treatment data.a

| Groups | Age (years) | BMI (kg/m2) | Mean monthly migraine frequency |

Mean monthly migraine days |

Responder rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-treatment | Baseline | Post-treatment | ||||

| 1 (n = 10) | 17.6 ± 1.5 | 22.36 ± 0.66 | 5.71 ± 1.4 | 4.75 ± 1.5 | 12.7 ± 1.34 | 11.85 ± 1.35 | 30 |

| 2 (n = 10) | 17.8 ± 1.4 | 23.14 ± 0.45 | 5.68 ± 1.6 | 5.22 ± 1.8 | 12.5 ± 1.72 | 11.65 ± 1.44 | 20 |

| 3 (n = 20) | 17.4 ± 1.7 | 23 ± 0.73 | 5.86 ± 1.2 | 2.6 ± 0.98 | 12.32 ± 1.85 | 5.74 ± 1.25 | 85 |

Data are given as mean ± SD following 2-month therapy.

Figure 1.

Mean monthly migraine frequency in migraineur school girls treated with either topiramate (50 mg/d) or thioctic acid (300 mg/d) or a combination of both. ∗Significantly different from baseline at p ⩽ 0.05, paired student t-test.

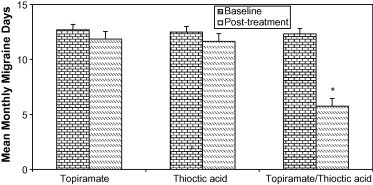

The mean change from baseline in monthly migraine days (Table 1 and Fig. 2) was significantly greater for patients receiving combined topiramate/thioctic acid therapy but not for those receiving either topiramate 50 mg/d or thioctic acid 300 mg/d monotherapies. Combined topiramate/thioctic acid therapy decreased the mean monthly migraine days from 12.32 ± 1.85 to 5.74 ± 1.25 (p ⩽ 0.05), topiramate (50 mg/d) from 12.7 ± 1.34 to 11.85 ± 1.35 and thioctic acid (300 mg/d) from 12.5 ± 1.72 to 11.65 ± 1.44.

Figure 2.

Mean monthly migraine days in migraineur school girls treated with either to piramate (50 mg/d), thioctic acid (300 mg/d) or a combination of both. ∗Significantly different from baseline at p ⩽ 0.05, paired student t-test.

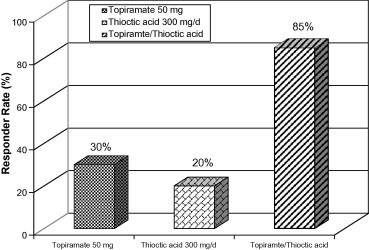

The responder rates (Table 1 and Fig. 3) were 30%, 20% and 85% for groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The responder rate is the percentage of patients showing ⩾50% reduction in monthly migraine frequency in each group.

Figure 3.

Responder rate (% of patients showing ⩾50% reduction in monthly migraine frequency) in migraineur school girls treated with either topiramate (50 mg/d), thioctic acid (300 mg/d) or a combination of both.

3.2. Safety measures

The most common ADRs observed are listed in Table 2. Higher incidence of ADRs mainly nausea (20%), fatigue (20%) paraesthesia (10%) and taste perversion (10%) was noted in patients receiving topiramate (50 mg/d) monotherapy.

Table 2.

Treatment-associated adverse reactions.

| Groups | Nausea | Fatigue | Paraesthesia | Taste perversion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 10) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 (n = 10) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 (n = 20) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

4. Discussion

Many antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are increasingly recommended for migraine prophylaxis because of many placebo-controlled double-blind trials that prove them effective (Silberstein, 2000). Other controlled clinical studies (Mathew et al., 1995; Klapper, 1997; Freitag et al., 2002) had examined the efficacy of AEDs in migraine prophylaxis. Divalproex sodium had a responder rate of 48% (Mathew et al., 1995), 44% (Klapper, 1997), and 41% (Freitag et al., 2002) in three placebo-controlled trials. Gabapentin had a responder rate of 36% compared with 14% with placebo (Mathew et al., 1999). These studies support the clinical value of AEDs for migraine prevention.

A number of clinical studies had also proven the efficacy of TCAs (Couch and Hassanein, 1979) and beta-adrenoceptor blockers (Tfelt-Hansen et al., 1984) in migraine prophylaxis.

The efficacy and safety of topiramate therapy as a migraine-preventive agent had been proved in many placebo-controlled double-blind trials (Diener et al., 2007; Silberstein et al., 2004, 2009). In a large, controlled trial (MIGR-001Study), topiramate at doses of 100 and 200 mg/d significantly reduced monthly migraine frequency and monthly migraine days but not topiramate 50 mg/d (Silberstein et al., 2004). The same trial concluded that topiramate 100 and 200 mg/d had responder rates of 54% and 52.3%, respectively, compared for placebo (Silberstein et al., 2004). The efficacy of topiramate in the prevention of migraine headache may be related to restoring the balance between the excitatory glutamate-mediated transmission and inhibitory GABA-mediated transmission in cerebral tissues, mainly in specific brain areas (Hamada, 2009).

One randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial (Magis et al., 2007) supports the clinical utility of thioctic acid (600 mg/d) for migraine prevention. Impaired mitochondrial phosphorylation potential had been implicated in migraine pathogenesis (Magis et al., 2007). The migraine-preventive effect of thioctic acid may be related to its antioxidant (Cronan et al., 2005) and mitochondrial bioenergetic (Magis et al., 2007) properties. Thioctic acid had been used clinically over many years with a good tolerability and safety record (Cremer et al., 2006).

5. Conclusion

In this randomized open-label study, combined topiramate (50 mg/d) and thioctic acid (300 mg/d) therapy was more effective in reducing monthly migraine frequency and migraine days with better responder rate compared with topiramate (50 mg/d) or thioctic acid (300 mg/d) monotherapies. In addition to significantly reducing mean monthly migraine frequency and migraine headache days, treatment with this combination was well tolerated and not associated with serious adverse events. The most common adverse reactions were nausea, fatigue and dysgeusia. Being more effective and better tolerated than topiramate monotherapy, we recommend the use of this combination in migraine prophylaxis. In addition, this combination has lower monthly medication costs compared to the traditionally used topiramate 100 mg monotherapy.

References

- Bolayir E., Celik K., Kugu N., Yilmaz A., Topaktas S., Bakir S. Intraerythrocyte antioxidant enzyme activities in migraine and tension-type headaches. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2004;67:263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carolyn J.H., Cassio L., Richard M.G. Migraine Headache. JAMA. 2009;301(24):2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.301.24.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinancarelli I., Tozzi-Ciancarelli M.G., Di Massimo C., Marini C., Carolei A. Urinary nitric oxide metabolites and lipid peroxidation by products in migraine. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:39–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon M.J., Sligar S.G., Irwin C. Gunsalus, versatile and creative scientist. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;12:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch J.R., Hassanein R.S. Amitriptyline in migraine prophylaxis. Arch. Neurol. 1979;36:695–699. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1979.00500470065013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer D.R., Rabeler R., Roberts A., Lynch B. Long-term safety of alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) consumption: a 2-year study. Long. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006;46:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan J.E., Fearnley I.M., Walker J.E. Mammalian mitochondria contain a soluble acyl carrier protein. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(21):4892–4896. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debruyne F., Herroelen L. Migraine presenting as chronic facial pain. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2009;109(3):235–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener H.C., Bussone G., Van Oene J.C., Lahaye M., Schwalen S., Goadsby P.J. Topiramate reduces headache days in chronic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(7):814–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers S., Afra J., Frese A., Goadsby P.J., Linde M., May A., Sandor P.S. EFNS guidelines on the drug treatment of migraine – report of an EFNS task force. Eur. J. Neurol. 2006;13(6):560–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers S., Afra J., Frese A., Goadsby P.J., Linde M., May A., Sandor P.S. European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) guidelines on the drug treatment of migraine-revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur. J. Neurol. 2009;16(9):968–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag F.G., Collins S.D., Carlson H.A. A randomized trial of divalproex sodium extended-release tablets in migraine prophylaxis. Neurology. 2002;58:1652–1659. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyuron B., Reed D., Kriegler J.S., Davis J., Pashmini N., Amini S. A placebo-controlled surgical trial of the treatment of migraine headaches. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009;124(2):461–468. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181adcf6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenen G.R.M.M., Bast A. Scavenging of hypochlorous acid by lipoic acid. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1991;42:2244–2246. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90363-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada J. Use of antiepileptic drugs for the preventive treatment of migraine. Brain Nerve. 2009;61(10):1117–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee, 2000 Guidelines for Controlled Trials of Drugs in Migraine, second ed. Cephalgia 20, 765–786. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Klapper J. Divalproex sodium in migraine prophylaxis. A dose-controlled study. Cephalgia. 1997;17:103–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1702103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch H.J., Jürgens T.P. Antidepressants in long-term migraine prevention. Drugs. 2009;1(69):1–19. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton R.B., Stewart W.F., Diamond S., Diamond M.L., Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:646–657. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magis D., Ambrosini A., Sandor P., Jacquy J., Laloux P., Schoenen J. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thioctic acid in migraine prophylaxis. Headache. 2007;47(1):52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew N.T., Jaffri S.F. A double-blind comparison of on a botulinum toxin a (BOTOX) and topiramate (TOPAMAX) for the prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine: a pilot study. Headache. 2009;49(10):1466–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew N.T., Saper J.R., Silberstein S.D. Migraine prophylaxis with divalproex. Arch. Neurol. 1995;52:281–286. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540270077022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew N.T., Magnus-Miller L., Saper J. Migraine prophylaxis with gabapentin. Headache. 1999;39:367. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.111006119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata E. Antidepressants in migraine prophylaxis. Brain Nerve. 2009;61(10):1131–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negoro K. Calcium antagonists in the prophylactic treatment of migraine. Brain Nerve. 2009;61(10):1135–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer L., Witt E.H., Tritscher H.J. Alpha-lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996;19:227–250. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00017-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomone S., Caraci F., Capasso A. Migraine. An overview. Open Neurol. J. 2009;1(3):64–71. doi: 10.2174/1874205X00903010064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura T., Kowa H., Nakano T., Kitano A., Marukawa H., Urakami K., Takahashi K. Platelet superoxide dismutase in migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 1994;14:215–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1994.014003215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein S.D. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55:754–762. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein S.D., Lipton R.B., Godsby P.J. second ed. Martin Dunitz; Oxford, England: 2002. Headache in Clinical Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein S.D., Neto W., Schmitt J., Jacobs D. Topiramate in migraine prevention. Arch. Neurol. 2004;61:490–495. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein S., Lipton R., Dodick D., Freitag F., Mathew N., Brandes J., Bigal M., Ascher S., Morein J., Wright P., Greenberg S., Hulihan J. Topiramate treatment of chronic migraine: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of quality of life and other efficacy measures. Headache. 2009;49(8):1153–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun-Edelstein C., Mauskop A. Foods and supplements in the management of migraine headaches. Clin. J. Pain. 2009;25(5):446–452. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31819a6f65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. Botulinum toxin type-A (BOTOX) in the treatment of occipital neuralgia: a pilot study. Headache. 2008;48:1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tfelt-Hansen P., Standnes B., Kangasneimi P., Hakkarainen H., Olesen J. Timolol vs propranolol vs placebo in common migraine prophylaxis: a double-blind multicenter trial. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1984;69:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1984.tb07772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi-Ciancarelli M.G., De Matteis G., Di Massimo C., Marini C., Ciancarelli I., Carolei A. Oxidative stress and platelet responsiveness in migraine. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:580–584. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1705580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuncel D., Tolun F.I., Gokce M., İmrek S., Ekerbiçer H. Oxidative stress in migraine with and without aura. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2008;126:92–97. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikelis M., Rapoport A.M. Role of antiepileptic drugs as preventive agents for migraine. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(1):21–33. doi: 10.2165/11310970-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]