Abstract

Mitochondrial complex I inhibition has been implicated in the degeneration of midbrain dopaminergic (DA) neurons in Parkinson’s disease. However, the mechanisms and pathways that determine the cellular fate of DA neurons downstream of the mitochondrial dysfunction have not been fully identified. We conducted cell-type specific gene array experiments with nigral DA neurons from rats treated with the complex I inhibitor, rotenone, at a dose that does not induce cell death. The genome wide screen identified transcriptional changes in multiple cell death related pathways that are indicative of a simultaneous activation of both degenerative and protective mechanisms. Quantitative PCR analyses of a subset of these genes in different neuronal populations of the basal ganglia revealed that some of the changes are specific for DA neurons, suggesting that these neurons are highly sensitive to rotenone. Our data provide insight into potentially defensive strategies of DA neurons against disease relevant insults.

Introduction

Although many neuronal populations are affected in Parkinson disease (PD), dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNC) are among the most severely affected and their death leads to major neurological disability (Hirsch et al., 1988; Fearnley and Lees, 1991). With the exception of rare hereditary forms of the disease, the causes of PD are not known. Deletions of mitochondrial DNA (Bender et al., 2006) and a decreased activity of complex I of the respiratory chain (Schapira et al., 1989; Schapira et al., 1990; Mann et al., 1992; Swerdlow et al., 1996) have implicated mitochondrial dysfunction in the degenerative process occurring in sporadic PD. This hypothesis is further supported by evidence that two ion channels that are expressed by SNC-DA neurons render these neurons more susceptible to oxidative stress (Liss et al., 2005, Chan et al., 2007). Despite increasing knowledge about the mechanisms responsible for the vulnerability of DA neurons to oxidative stress, the downstream molecular responses to the insult are not well understood.

To identify cellular pathways and mechanisms that are activated at an early stage of mitochondrial dysfunction in SNC-DA neurons we performed transcriptional analysis of these neurons in rats treated with low doses of the mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone (Sherer et al., 2003a). Rotenone has been shown to reproduce key features of PD, including motor deficits and a variable loss of DA neurons and terminals (Betarbet et al., 2000; Alam and Schmidt, 2002; Sherer et al., 2003b, Fleming et al., 2004). However, the vulnerability of SNC-DA neurons to rotenone, and the selectivity of the insult highly depend on experimental conditions and vary in individual animals (Höglinger et al, 2003; Zhu et al., 2004).

For the present study, our goal was to produce a low level insult that possibly affected DA neurons without inducing rapid cell loss. Our previous studies have shown that after administration of 2.0 mg/kg/day s.c for 3 weeks, a high percentage of surviving animals have normal cell counts of DA neurons in the SNC and normal TH protein expression levels in the striatum despite their clearly detectable motor impairment (Fleming et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2004). To further reduce the risk of inducing a structural deficit, we reduced the exposure time to one week. We then selected a subset of animals with both weight loss and behavioral impairment but without a loss of tyrosine hydroxylase- (TH) positive fibers in the striatum, and performed transcriptome analyses of laser-capture microdissected DA neurons (Bonaventure et al., 2002; Kamme et al., 2004). The gene array experiments identified large scale transcriptional alterations in SNC-DA neurons with genes involved in the regulation of cell death comprising one of the most prominent functional categories. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses of a subset of these genes in GABAergic neurons of the substantia nigra (SN) and striatum revealed that the transcriptional activation is specific for SNC-DA neurons, indicating selectivity in the molecular response elicited by low cumulative doses of rotenone in this neuronal population.

Materials and Methods

In vivo rotenone administration

Adult male Lewis rats (Charles River Labs, Michigan), which have previously been shown to develop consistent rotenone induced lesions (Betarbet et al., 2000), were used in the current study. All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of California, Los Angeles and the US Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL)-Brooks Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. 34 animals received a continuous subcutaneous infusion of rotenone (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at 2mg/kg/d s.c. for one week via Alzet minipumps (Durect Corp., Cupertino, CA). The drug was dissolved in equal amounts of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and polyethyleneglycol (PEG). Control animals (n = 20) received vehicle infusions at the same flow rate. All animals were monitored daily for weight loss and signs of general distress such as apathy, irritability, and responsiveness to external stimuli. Treatment related behavioral deficits were assessed by quantifying rearing activity for 5 minutes on day 6 of the infusion period (Fleming et al., 2004). At the end of the treatment animals were decapitated and the brains were immediately frozen at −70°C. Optical density measurements of TH immunoreactivity in the striatum were used to determine rotenone effects on the abundance of TH-positive nigrostriatal terminals. In brief, 20 μm sections were cut from fresh frozen tissue, mounted on plain glass slides, air dried for 1 hour and stored at −80°C until further processing. Prior to immunostaining sections were brought to room temperature and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. The subsequent TH immunostaining and optical density measurements were performed as described previously (Fleming et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2004).

Gene array analyses of dopaminergic neurons

To determine the severity of the rotenone effect in vivo and to reduce the risk of including treatment failures in the rotenone group, selection criteria for inclusion of the rotenone-treated animals in the cell-type specific transcriptome analyses consisted of a weight loss over the duration of the treatment period and decreased rearing activity. Three rotenone-treated animals meeting these criteria, as well as three vehicle-treated rats, were used for DNA microarray analyses. Included animals were also required to have a lack of histologically detectable deficits in the nigrostriatal system, which was determined by immunohistochemical quantification of striatal TH abundance as described earlier. Differences between the treatment groups were evaluated by Student’s t-tests in Microsoft Excel.

For laser-capture microdissection (LCM) of DA neurons, the midbrain area containing the substantia nigra was cut in 10 μm serial sections. Sections were mounted on plain glass slides and stored at −80°C until further usage. DA cells were identified by immunohistochemical labeling of tyrosine hydroxylase. Following a brief ethanol fixation (Bonaventure et al., 2002), sections were incubated with a polyclonal primary and a biotinylated secondary antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) for five minutes each. The Vectastain Elite ABC Kit and the DAB Substrate Kit (both Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), which were applied to the sections for three minutes each were used for chromogenic detection of antibody binding. Sections were rinsed in 1x phosphate buffered saline between each incubation step. For visualization of TH negative neurons sections were counterstained with cresylviolet for one minute. This step increases the selectivity of the laser-capture microdissection as it decreases the probability of contaminating the TH-positive samples with TH-negative cells. The entire procedure was carried out under RNase-free conditions. Duplicate samples of 200 TH-positive neurons were collected from each animal. RNA extraction and the first round of T7-based mRNA amplification were performed as described previously (Kamme et al., 2004). For the second round of amplification the Affymetrix IVT labeling kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) was used in order to generate biotinylated RNA samples that are suitable for hybridization to Affymetrix oligonucleotide microarrays. All samples were hybridized to the rat whole genome array 230 2.0 according to the manufacturer’s instructions in the UCLA microarray core unit. The array contains approximately 28,700 unique features (Affymetrix).

Statistical analyses of microarray data

The scanned microarray image files were imported into the R statistical software package (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, www.r-project.org). Within R (version 2.2.1) the Bioconductor package (version 1.6) was used to perform GCRMA background correction and quantile normalization of the data. Computation of the expression indices was based on the GCRMA method (Wu et al., 2003). The gene expression values for the duplicate samples of each animal were averaged to one sample value. Differentially expressed genes were identified based on two criteria: a present - absent call ratio larger than 1 (>50% present), and a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) model with gene expression as the outcome and group, treatment, and group-by-treatment interaction as the terms of the model. To assess the significance of the effects in the ANOVA model we computed the false discovery rate (FDR) based on the empirical bayes methodology discussed in Efron and Tibshirani (2002). Briefly, the empirical bayes method estimates the FDR by comparing the empirical distribution of the test statistics (in this case the F-statistics for each model effect) with the theoretical probability distribution of the F-statistics across the set of genes. The primary inference was for the rotenone treatment effect. Genes were considered to be differentially expressed with FDR< 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R.

Overrepresentation of gene families and clusters of biological and molecular functions in the differentially expressed genes was assessed in the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, www.david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) and the Protein Analysis Through Evolutionary Relationships (Panther, www.pantherdb.org) classification system. The DAVID database was also used to verify and up-date gene annotations provided by Affymetrix. In addition to these database analyses extensive literature searches were conducted for all 453 differentially regulated genes. This effort to up-date the database annotations was particularly geared towards identifying more cell death related genes.

Quantitative real-time PCR analyses of cell death related gene expression in select neuronal populations

Differentially regulated genes that were identified in the array screening experiments were validated by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analyses. In order to increase the sample size in each of the two treatment groups and thus increase the probability of detecting differential gene expression, qPCR experiments were performed with an extended group of animals (n = 6 for both control and rotenone treated groups). In accordance with the criteria used for selecting animals for the array experiments, the three additional rotenone treated animals were chosen from the subgroup that exhibited both weight loss and reduced rearing activity. The relevance of these selection criteria and their potential impact on gene expression changes was tested by qPCR analyses in a set of rotenone treated animals that did not show a toxin induced weight loss or a reduction in rearing activity (n = 6 for both control and rotenone treated groups). Differences in weight and behavior between the treatment groups in both sets of animals were evaluated by Student’s t-tests in Microsoft Excel.

In order to exclude that the array data are an artifact of the T7-based RNA amplification, non-amplified RNA samples from laser-dissected DA neurons served as template in the qPCR experiments. On average 150 cells were used for each gene and cell type. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed as described in the T7 amplification protocol above. Negative controls were generated by omitting the reverse transcriptase in the cDNA synthesis step. qPCR experiments were carried out in an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (ABI, Foster City, CA) or a Roche LightCycler 480 using the Roche LightCycler FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I mix (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). All samples including serial plasmid dilutions for generating standard curves were run in triplicates. Primers were added at a final concentration of 400 nM. Aldo-keto reductase 1a1 (aldehyde reductase) and peptidylprolyl isomerase A (cyclophilin A) were used for normalization of RNA content. These genes were chosen because they are abundantly expressed and the results of the prior array analysis demonstrated a lack of treatment dependent changes in expression levels. Average mRNA quantities of both genes were calculated for each sample and the combined values served as normalization factors. For each gene standard curves were generated from 10-fold serial dilutions of plasmid clones. Calculation of absolute quantities was performed on ABI Prism 7900HT or LightCycler 480 software. In addition to the melting curve analysis, an agarose gel electrophoresis was performed for each gene to ensure that the amplification resulted in a single product of the correct size. Statistical significance of group differences was determined by the Student’s t-test statistics (Microsoft Excel) with p-values < 0.05 considered to be significant.

Phenotypic characterization of neuronal populations used in qPCR experiments

In addition to DA neurons, TH-negative GABAergic neurons of the SN were collected from the same sections. GABAergic neurons were identified as large cresylviolet-positive and TH-negative cells in the reticular part of the SN. For both cell types samples of 5 individually dissected neurons were generated as described above. TH and glutamic acid decarboxylase 1 (Gad1) were chosen as markers for DA and GABAergic neurons, respectively. In addition, medium sized neurons (GABAergic) were captured from the central portion of the striatum just rostral of the anterior commissure. The striatal sections were briefly stained with cresylviolet (Kamme et al., 2004). All of these validation experiments were carried out with duplicate samples. Primer sequences for the PCR experiments were as follows: TH forward: TGAAGTTTGACCCGTACACACTGG, TH reverse: GGTCCAAGAGGAGCCCATCAAAGG, Gad1 forward: CCAGCAATTACTAAGAGGCTAACC, Gad1 reverse: CTTCCTGCCATCCATCATCCATCC. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed as described above. Negative controls for each cell type consisted of samples, in which the reverse transcriptase had been omitted in the cDNA synthesis step. PCR experiments were conducted in a Roche Light Cycler I system using the LightCycler FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I mix (Roche Diagnostics). Primers were added at a final concentration of 400 nM. Annealing temperatures for all primer pairs were 60°C and amplifications were carried out for 40 cycles. All PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Results

Animals selected for the transcriptome analyses showed a mild weight loss and decreased exploratory motor behavior

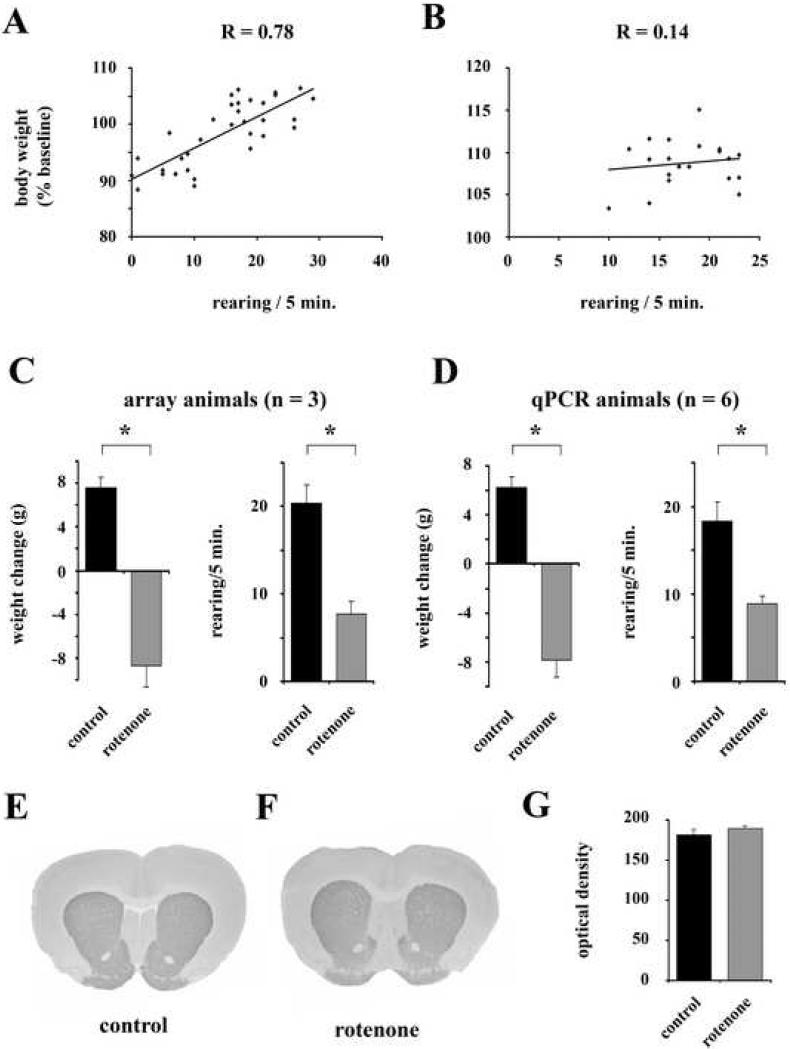

In the present study 34 male Lewis rats received continuous subcutaneous rotenone infusions of 2mg/kg/day for one week. This dose had only mild toxic effects as indicated by the high survival rate (33 out of 34 animals), and previously demonstrated absence of DA neuron loss in the SNC (Fleming et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2004). Except for the animal that died on day four of the treatment period, there were no signs of general distress, such as irritability or reduced responsiveness to external stimuli. To avoid including treatment failures, we required that each animal displayed a weight loss and previously described rotenone-induced reduction in rearing activity (Fleming et al., 2004). Even though both parameters showed considerable variability within the rotenone group, which is in agreement with a wide range of individual susceptibility and responsiveness to the toxin (Höglinger et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2004) there was a significant positive correlation between the reduction in body weight and the number of rearings at the end of the seven day infusion period (Fig. 1A, B). For the initial array experiments (n = 3 in each group) as well as the subsequent qPCR validation of the array data (n = 6 in each group) rotenone treated animals were chosen from the subgroup that exhibited weight loss and decreased rearing during the treatment. Statistical analyses revealed that in both cohorts the rotenone treated animals were significantly different from control animals for change in weight and number of rearings (Fig. 1C, D). The lack of histologically detectable abnormalities in the nigrostriatal system was confirmed by densitometric measurements of TH immunoreactivity in the striatum. Animals selected for the array and qPCR experiments did not show a decrease in TH staining intensity (Fig. 1E - G). In order to test the relevance of these criteria for potential gene expression changes we composed an additional set of rotenone treated animals (n = 6 in each group) that did not experience a reduction in weight over the course of treatment (weight gain: control: 12.0 % from baseline ± 0.7 (mean ± SEM), rotenone: 6.1 ± 0.7). Both groups did not differ in rearing activity (control: 18.6 ± 1.6 rearings/5min (mean ± SEM), rotenone: 21.6 ± 1.8), confirming the correlation between weight loss and behavioaral deficits. There was also no difference in TH immunoreactivity in the striatum (Fig. 1G).

Fig. 1.

Selection criteria for animals included in the array screening and qPCR experiments. A, B. Scatter plots of change in body weight (baseline = 100) and number or rearings during a 5 minute observation period for all rotenone treated (n = 33) (A) and control (n = 20) (B) animals. Data for the behavioral parameter were collected on day six and data for calculation of weight change were collected on day seven of the treatment period. C. Comparisons of weight change (baseline = 0) and rearing activity for the group of animals used in the microarray experiments (n = 3 in both control and rotenone treated groups). D. Same comparisons for the animals that were used in the qPCR validation experiments (n = 6 in both control and rotenone treated groups). E, F. TH immunohistochemical staining of the striatum just rostral of the anterior commissure. 20 μm coronal sections. G. Optical density (OD) measurements of TH-stained striatal sections. The data include all animals used for transcriptional profiling experiments in this study. All error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). * indicates p < 0.05.

Low-dose rotenone treatment causes multiple transcriptional alterations in DA neurons

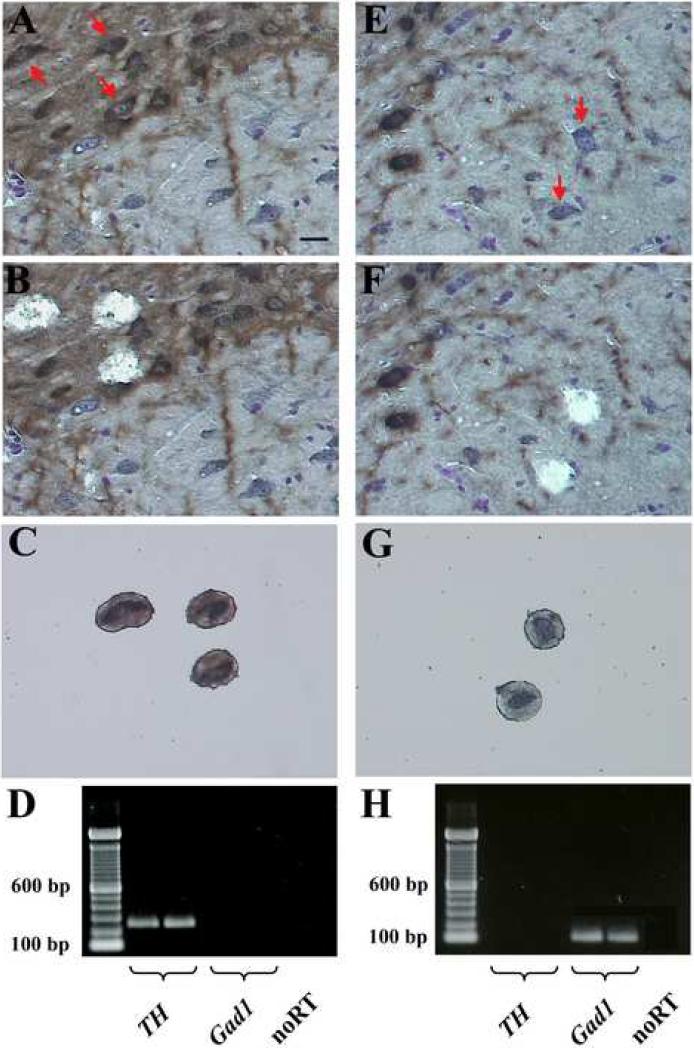

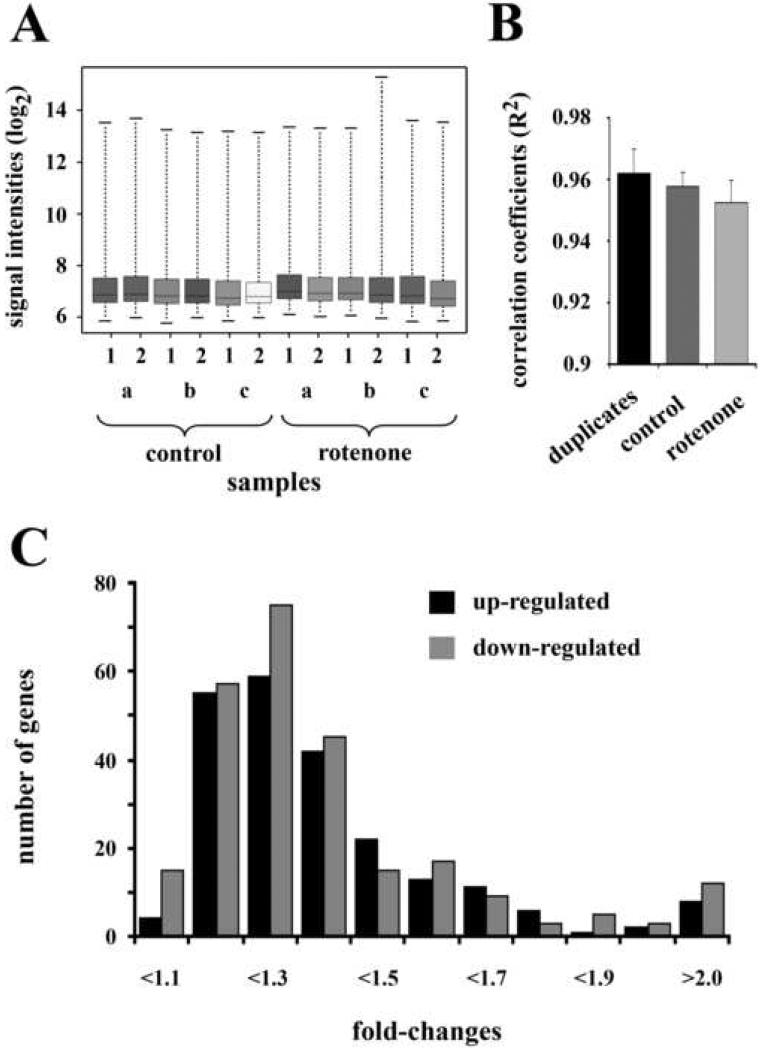

Cell-type specific transcriptome analyses were conducted with laser-capture microdissected DA neurons from the SNC. Duplicate samples of 200 TH immunoreactive neurons (Fig. 2A – C) were generated from each animal (n = 3 in each group) and the two-round amplified RNA was hybridized to Affymetrix rat whole genome microarrays. Prior to identifying differentially regulated genes, we assessed the quality and reproducibility of the array data within the control and rotenone treated groups. At the technical level background hybridization signals (control 71.5 ± 1.13, rotenone 73.8 ± 2.29 (mean ± SEM)), percentage of expressed genes (control 57.6 ± 0.32, rotenone 57.9 ± 0.41 (mean ± SEM)), and the overall distribution of signal intensities (Fig. 3A) were highly similar for all arrays. The average correlation coefficients (R2) of all array samples, which provide a combined estimate of the technical and biological variability, were almost identical in both treatment groups. In addition, these values did not differ from the average correlation coefficient of the duplicate samples generated from each animal (Fig. 3B). Together these data demonstrate a high degree of reproducibility and ensure the comparability of the array results from control and rotenone treated animals.

Fig. 2.

Laser-capture microdissection of DA and GABA expressing neurons in the SN. 10 μm TH-stained sections. A – C. TH-positive neurons before (A) and after (B) laser microdissection. C. Captured neurons. E – G. GABAergic neurons before (E) and after (F) laser microdissection. G. Captured neurons. D, H. PCR verification of marker gene expression (TH for DA neurons and Gad1 for GABAergic neurons) confirm the correct phenotype and the purity of the DA (D) and GABA (H) samples. Red arrows (A, E) indicate dissected neurons. Scale bar: 20 μm.

Fig. 3.

Expression profiling of laser dissected DA neurons from control (n = 3) and rotenone treated (n = 3) animals. A. Box plots of the signal intensity distribution (log2) of all arrays before normalization. B. Correlation coefficients of hybridization intensities (after normalization) for duplicate samples of each animal, and all samples within the control and rotenone treated groups. The latter two do not contain comparisons of duplicate samples. Error bars represent SEM. C. Fold-change distribution of all genes with significant (p < 0.05) mRNA expression changes.

Statistical analyses revealed that a total number of 453 genes were differentially expressed in the rotenone treated group (p < 0.05). This amounts to 1.58% of all genes represented on the array or 2.75% of the genes found to be expressed in DA neurons. 214 of these genes showed an increased expression, whereas for 239 the mRNA levels were decreased. For both up- and down-regulated genes the vast majority of the changes were smaller than 2-fold (Fig. 3C). Annotations were available for 332 of the 453 differentially regulated genes. The complete list of genes is available in Supplemental Table S1. Database searches for pathways and biological processes (DAVID and Panther) that are overrepresented in the list of differentially regulated genes indicated that the low dose rotenone treatment induced changes in several Gene Ontology (GO) categories (Table 1). However, these terms and categories are very general and do not reveal any detailed information about more specific pathways. In particular the analyses were not informative with regard to cell death and survival related genes. One of the potential reasons for this failure to detect correlated changes in gene expression by database searches is that the functional annotations are either incomplete or not entirely up to date. We therefore performed extensive literature analyses of all differentially regulated genes. A compilation of the most prominent functional categories revealed that rotenone treatment altered the transcription signature of a broad range of cellular processes and compartments (Table 2). In particular, the large number of transcription factors and regulators of transcription supports the notion of a shift in functional profiles. Although transcription factors undoubtedly constitute critical components of the adaptive response to the toxin, we chose to focus on cell death related genes for further analyses because these are likely to be most relevant for determining the fate of dopaminergic neurons in response to low dose rotenone, and by extension, chronic alterations in mitochondrial function, which may play a role in Parkinson’s disease.

Table 1.

GO categories overrepresented in differentially regulated genes

| GO category | GO ID | number of genes |

p-value (Benjamini) |

|---|---|---|---|

| intracellular | GO:0005622 | 151 | 0.0004 |

| biological regulation | GO:0065007 | 100 | 0.002 |

| binding | GO:0005488 | 193 | 0.004 |

| regulation of biological process | GO:0050789 | 88 | 0.0092 |

| intracellular part | GO:0044424 | 135 | 0.022 |

| regulation of cellular process | GO:0050784 | 78 | 0.034 |

Table 2.

Differentially regulated gene families

| gene category | number of genes changing |

|---|---|

| transcriptional regulation | 36 |

| regulation of cell death/apoptosis | 24 |

| mitochondrial function | 12 |

| ubiquitination/proteasome function | 10 |

| nucleotide related signaling | 7 |

| cell adhesion | 7 |

| calcium binding | 6 |

| neurotransmitter synthesis and release | 4 |

| microtubule associated genes | 3 |

| ion channels | 3 |

| peroxisomal functions | 2 |

The under-representation of certain functional categories in public databases is particularly evident in cell death and survival related genes. The Affymetrix annotations, which were confirmed by analyses in DAVID revealed only 8 genes within the apoptosis or cell death categories, and 4 genes with a ‘cell proliferation’ or ‘cell growth’ annotation (Table 3). Among the remaining 441 differentially expressed genes, our literature analysis identified 12 additional genes with a clear association to either cell death or cell survival. Representative references are given in Table 3. These data demonstrate that although useful as initial screening tools database searches might return a considerable number of false negative results.

Table 3.

Cell death and survival associated genes. GO annotation and literature references

| Entrez Gene ID |

type of change |

GO annotation | references |

|---|---|---|---|

| cell death inhibitors | |||

| Aven | up | 0006916: anti-apoptosis | |

| Opa1 | up | 0006915: anti-apoptosis | |

| Polb | up | 0006916: anti-apoptosis | |

| Flt1 | up | 0008284: cell proliferation | |

| Nmt2 | up | no cell death association |

Selvakumar et al., 2006

Selvakumar et al., 2007a,b; Ducker et al., 2005; |

| Rrm2 | up | no cell death association |

Duxbury et al., 2004; Xue et al.,2003 |

| Hspb6 | up | no cell death association | Fan et al., 2004 |

| Cirbp | up | no cell death association | Sakurai et al., 2006 |

| Cfdp1 | down | 0006916: anti-apoptosis | |

| Spdya | down | 0008284: cell proliferation | |

| Zfp259 | down | no cell death association | Doran et al., 2006 |

| Tmem132a | down | no cell death association | Oh-hashi et al., 2003 |

| cell death inducers | |||

| Caspase 11 | up | 0006917: apoptosis | |

| Ing1 | up | 0030308: cell growth | |

| Txnip | up | no cell death association |

Junn et al., 2000; Minn et al., 2005 |

| Aifm2 | down | 0006915: apoptosis | |

| Gadd45g | down | 0006915: apoptosis | |

| Cradd | down | 0008625: apoptosis | |

| Ing2 | down | 0001558: cell growth | |

| Adcyap1 | down | no cell death association | Li et al., 2005 |

| Enc1 | down | no cell death association |

Polyak et al., 1997; Hammarsund et al., 2004; Katayama et al., 2003 |

| Npdc1 | down | no cell death association | Galiana et al., 1995 |

| Taok3 | down | no cell death association | Wakabayashiet al., 2005 |

| Spint2 | down | no cell death association | Morris et al., 2005 |

According to previously published functional profiles all of these genes can be classified as either promoting or inhibiting cell death. One of the important factors that will determine the biological consequences of the altered expression is the type of change, i.e. increased or decreased mRNA levels. Inclusion of these data into the table revealed that both up- and down-regulation of expression occur in either category. However, most of the cell death inhibiting genes showed an increased expression, whereas the cell death promoting genes had mainly decreased mRNA levels (Table 3). These data indicate that low dose rotenone treatment for one week causes a simultaneous induction of degenerative and protective mechanisms with a clear emphasis on protective events.

Low dose of rotenone alters the transcription of distinct cell death-related genes

The validation of microarray data by qPCR focused on genes that represent a range of presumed function based on our extensive literature analysis. In particular we chose examples where changes were observed for only one member of a large gene family and that had not been previously associated with cell death or survival in DA neurons. In addition, we wanted to determine whether these effects were specific for nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons or represent general changes that also occur in the other populations of basal ganglia neurons. qPCR validation experiments were carried out with non-amplified RNA samples from re-captured DA neurons to exclude the possibility that the differences in expression levels are an artifact of cell sampling or the T7 RNA amplification procedure. The correct phenotype of the neurons, in particular the distinction from GABAergic neurons within the SN was verified by PCR analyses of the marker genes TH and GAD1 (Fig. 2D).

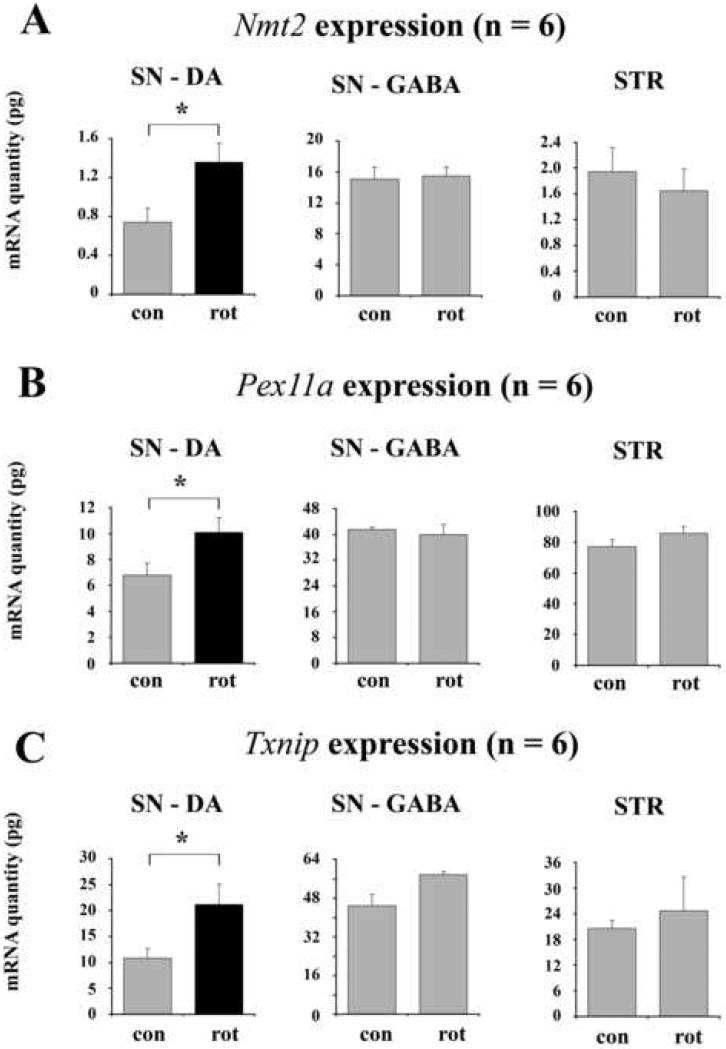

Within the groups of cell death and oxidative stress related genes, the qPCR analyses confirmed the array results for N-myristoyl transferase 2 (Nmt2), peroxisomal biogenesis factor 11a (Pex11a), and thioredoxin-interacting protein (Txnip) (Fig. 4A, B, C). In all 3 cases the expression levels were up regulated. Nmt2, a negative regulator of apoptosis (Ducker et al., 2005), catalyzes the transfer of myristic acid to N-terminal glycine residues of signal transduction proteins. The reaction is part of the post-translational maturation process (Selvakumar and Sharma, 2007). Although both currently known N-myristoyl transferases were found to be expressed in the array data, only Nmt2 showed a significant change of its mRNA level (Table 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4 qPCR analysis of cell death related gene expression. A – C. The mRNA levels of Nmt2 (A), Pex11a (B), and Txnip (C) were assessed in DA and GABAergic neurons of the SN, as well as in the population of striatal projection neurons. Con and rot indicate samples from control (n = 6) and rotenone treated (n = 6) animals. All error bars represent SEM. * indicates p < 0.05.

Table 4.

Expression levels (array data) of index gene families. Index genes are highlighted in gray.

| Affymetrix ID |

Entrez Gene symbol |

fold- change |

p-value | hybridization signal intensity (log2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean control |

mean lesion |

background | ||||

| 1391256_at | Nmt2 | 1.505 | 0.0089 | 6.06 | 6.65 | |

| 1375522_at | Nmt1 | −1.148 | 0.0515 | 9.22 | 9.02 | |

| 1371131_a_at | Txnip | 2.657 | 0.0134 | 8.05 | 9.46 | |

| 1398839_at | Txn1 | −1.086 | 0.3577 | 13.01 | 12.89 | |

| 1398844_at | Txn2 | 1.021 | 0.9107 | 8.39 | 8.42 | |

| 1398791_at | Txnrd1 | 1.042 | 0.6253 | 9.19 | 9.25 | |

| 1368309_at | Txnrd2 | −1.021 | 0.7956 | 6.1 | 6.07 | |

| 1373274_at | Txnrd3 | 1.057 | 0.5577 | 6.79 | 6.87 | |

| 1379361_at | Pex11a | 1.356 | 0.0078 | 6.56 | 7 | |

| 1370833_at | Pex2 | −1.035 | 0.7252 | 9.37 | 9.32 | 6.18 |

| 1368526_at | Pex3 | 1.064 | 0.6354 | 8.35 | 8.44 | |

| 1371431_at | Pex5 | −1.028 | 0.5551 | 9.18 | 9.14 | |

| 1368264_at | Pex6 | 1.028 | 0.6671 | 5.51 | 5.55 | |

| 1379784_at | Pex7 | −1.148 | 0.6144 | 6.08 | 5.88 | |

| 1372923_at | Pex11b | 1.006 | 0.9481 | 7.76 | 7.77 | |

| 1393668_at | Pex11c | 1.394 | 0.0135 | 3.28 | 3.76 | |

| 1369070_at | Pex12 | 1.265 | 0.0687 | 7.32 | 7.66 | |

| 1374638_at | Pex13 | 1.006 | 0.9523 | 8.79 | 8.8 | |

| 1370306_at | Pex14 | 1.021 | 0.7084 | 5.85 | 5.88 | |

| 1383960_at | Pex16 | 1.141 | 0.4267 | 6.1 | 6.29 | |

| 1388350_at | Pex19 | 1.071 | 0.6303 | 7.46 | 7.56 | |

The second gene with an increased expression in the array experiments that was selected for qPCR validation was Pex11a. The gene has previously been shown to regulate peroxisomal abundance (Schrader and Fahimi, 2006) and therefore might play a role in the response to oxidative stress. The peroxisomal biogenesis factors form a large family of genes. With the exception of Pex11c, which has an expression level significantly below background, all of the family members represented on the array were found to be expressed in DA neurons of the SNC. However, none of these genes showed any significant alterations of transcriptional activity (Table 4). The up-regulation of Pex11c (Table 4) could not be validated by qPCR (data not shown), which could be due to the low expression levels or might represent a false positive result of the array technology.

In contrast to Nmt2 and Pex11a, Txnip has been shown to act as a positive regulator of cell death, e.g. in response to oxidative stress (Chung et al., 2006). The gene is a member of the thioredoxin oxidoreductase system and its protein product has been shown to bind to and inhibit thioredoxin activity (Nishiyama et al., 1999). A search for related genes in the entire array data set revealed that all members of the thioredoxin- and thioredoxin reductase families are expressed in DA neurons but that they do not change their expression levels in response to rotenone treatment (Table 4). Thus the transcriptional regulation of the thioredoxin system is restricted to Txnip. In addition, none of the genes in the glutathione – glutaredoxin or superoxide dismutase systems was regulated at the transcriptional level (data not shown). These data demonstrate that the transcriptional alterations are targeted specifically towards individual members of larger gene families, all or almost all of which are expressed under physiologic conditions.

In order to test whether the initial criteria for animal selection, i.e. weight loss and a reduced rearing activity, bear any relevance for the changes in gene expression, we analyzed an additional group of rotenone treated animals (n = 6 in both groups) that did not exhibit a weight loss or differ from the control group in rearing activity. qPCR analyses of Nmt2 (control: 9.2 ng ± 1.6 (mean ± SEM), rotenone: 7.7 ng ± 1.9) and Txnip (control: 33.7 ng ± 7.1, rotenone: 41.7 ± 4.4) revealed similar expression levels for both genes in control and rotenone treated animals. These data indicate that there is a threshold effect for changes in gene expression that correlates with weight loss and decreased number of rearing movements.

A subset of the transcriptional changes induced by rotenone is specific for DA neurons

The question, whether the differential mRNA regulation of Nmt2, Pex11a, and Txnip is specific for DA neurons or represents a rather general response that occurs in different neuronal phenotypes throughout the brain, was addressed by qPCR analyses in GABAergic projection neurons of the substantia nigra pars reticulata and the striatum. In particular, striatal neurons have previously been shown to be sensitive to higher cumulative doses of rotenone (Höglinger et al., 2003; Lapointe et al., 2004, Zhu et al., 2004). GABAergic neurons in the SN that were identified as large Nissl stained TH-negative cells in the reticular part of the nucleus, were captured from the same TH-labeled sections that were used for collecting DA neurons (Fig. 2E – G). Again, the correct phenotype of the cells and the purity of the samples were verified by PCR analyses of the marker genes Gad1 and TH (Fig. 2H). Striatal neurons, which predominantly consist of medium spiny projection neurons were identified by their medium size in cresylviolet stained sections. The qPCR results revealed that Nmt2, Pex11a, and Txnip did not change their transcriptional levels in GABAergic neurons of the SN or striatum (Fig. 4 A, B, C).

Discussion

The main goal of our experiments was to study the transcriptional response of DA neurons in the SNC to mild rotenone-induced cellular stress. Therefore, dose and duration of treatment were designed to minimize histologically detectable structural defects of the nigrostriatal system. Our goal was to avoid the relatively acute cell death induced by higher doses of the toxin (Betarbet et al., 2000; Scherer et al., 2003, Hoeglinger et al., 2003), which would likely bias the analysis towards late stage degenerative processes. The behavioral criteria together with the weight loss were used to select animals that have a clear effect of rotenone compared to vehicle treated controls. We have previously demonstrated an association of multiple behavioral deficits with a similar low dose rotenone treatment (Fleming et al., 2004). However, the mechanisms of these anomalies and their potential relation to the gene expression changes in the nigrostriatal system remain unclear and were not further investigated in this study.

Our data demonstrate that at this low level of rotenone exposure DA neurons change their transcriptional profiles in a broad range of cellular functions. For several of the affected functions and pathways the altered expression selectively affects single members of a larger family of genes, suggesting that these might represent transcriptional control points. Within the group of cell death related genes the pattern of regulation indicates a simultaneous activation of protective and degenerative mechanisms. Both cell survival and cell death promoting genes were found to be up- and down-regulated. These data are in agreement with reports about stress responses in cell culture experiments that describe a concomitant activation of multiple antagonistic pathways (Ryu et al., 2004; Yew et al., 2005). Under the conditions chosen in our experiment the vast majority of survival promoting genes was up-regulated whereas most of the pro-apoptotic genes were down-regulated. The regulation of survival and death related genes in opposite directions most likely reflects a biological mechanism in the adaptive response to rotenone and does not represent an artifact of the array technology. If the overrepresentation of the up-regulated mRNA levels were merely due to a technical bias towards increased expression, then the overrepresentation of down-regulated pro-apoptotic genes would not be expected. The fact that there are very similar numbers of up- and down-regulated genes in the entire dataset also argues against the presence of a technical bias. With regard to their potential biological significance, these results suggest that cellular decisions about survival and apoptosis are made on a genomic scale and depend on the functional balance of a large number of antagonistic pathways.

In order to confirm this simultaneous activation of protective and degenerative pathways we selected genes for qPCR validation that are representative for both types of changes, and that had not been previously associated with molecular responses of DA neurons to cellular stress. Nmt2, which catalyzes the N-terminal myristoylation of signal transduction proteins (Selvakumar and Sharma, 2007) has multiple links to apoptosis. In human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells, siRNA mediated suppression of Nmt2 expression resulted in a 19-fold increase in apoptosis (Ducker et al., 2005). In addition, the gene has been shown to be inducible by various types of carcinogens such as dioxin (Kolluri et al., 2001) and elevated levels of Nmt2 expression have been described in multiple tumor tissues (Lu et al., 2005; Selvakumar and Sharma, 2007). These data, albeit all generated in malignant cells and tissues, suggest an anti-apoptotic function of the up-regulated expression.

Equivalent to Nmt2 the up-regulation of Pex11a expression most likely has a protective effect. The gene increases the abundance of peroxisomes in response to external stimuli (Schrader et al., 1998; Li et al., 2002). In HepG2 cell cultures increased Pex11a mRNA levels were mediated through stimulation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPAR) (Schrader et al., 1998). Besides apparent biochemical effects such as increased peroxisomal lipid beta-oxidation and catalase mediated H2O2 degradation, stimulation of PPARs has been shown to induce malignant tumors in the liver of rodents (Roberts, 1996). Recent experiments in various models of central nervous system diseases including the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) mouse model of PD have confirmed protective and anti-apoptotic effects of PPAR agonists in neurons (Breidert et al. 2002; Qi et al., 2004; Fuenzalida et al., 2007). These experiments also established a functional relationship between peroxisomes and mitochondria as cells expressing mutant PPARs were highly sensitive to oxidative stress (Fuenzalida et al., 2007). Together these data demonstrate that Pex11a regulates peroxisome abundance, which most likely results in a protective effect against cellular stress.

In contrast to Nmt2 and Pex11a, Txnip causes an induction of apoptosis (Yoshida et al., 2005). The cell death promoting effects are most likely due to an inhibition of the thioredoxin oxidoreductase system (Yoshida et al., 2005) that occurs both at the protein and mRNA levels (Nishiyama et al. 1999). In agreement with these data overexpression of Txnip increases oxidative stress (Schulze et al., 2004) and sensitizes HeLa cells to paraquat (Joguchi et al., 2002). Evidence for a similar function of Txnip in vivo originates from expression analyses in pancreatic islet cells of insulin resistant diabetic mice. The elevated Txnip mRNA levels are thought to contribute to the progressive loss of these cells (Minn et al., 2005). Pro-apoptotic effects of Txnip have also been deduced from expression analyses in various tumor cells that generally showed a significant down-regulation or loss of expression (Nishinaka et al., 2004; Ohata et al., 2005). These data suggest that the rotenone induced increase in Txnip transcription might have a detrimental effect on the survival of DA midbrain neurons.

Our experiments identified transcriptional activation of several different cell death related genes that have previously not been associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in DA neurons of the SNC in vivo. Array experiments in mouse models that used the mitochondrial complex I inhibitor MPTP did not detect differential regulation in any of the three genes described above (Grünblatt et al., 2001; Gu et al., 2003, Miller et al., 2004). Besides different mechanisms of action of the two toxins the presence of cell death, which indicates a higher level of severity of the cellular insult might account for the differences in transcriptional responses.

One motivation for identifying specific patterns of gene regulation in response to cellular stress in DA neurons of the SNC is the particular vulnerability of these neurons in PD. Although it is not known whether rotenone-induced cellular effects are similar to those occurring in PD, the ability of this toxin to selectively kill or alter DA neurons of the SNC under certain experimental conditions has led to its use as a model of PD (Betarbet et al., 2000; Scherer et al., 2003b). However, the transcriptome changes discovered in this study were different from those previously reported in post-mortem human PD brains (Grünblatt et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2006), even when laser capture microdissection of DA neurons was used (Cantuti et al., 2006). This discrepancy is not surprising as post-mortem analyses reflect a long term disease process with substantial neuronal loss and years of pharmacological treatment, conditions that are very different from those produced by our experimental procedure, which focused on early responses of DA neurons to a moderate cellular stress. The recent recognition that incidental Lewy Body disease may represent an early, pre-clinical, stage of PD may offer the possibility to examine the transcripts we have identified in human DA neurons at risk of developing the disease (Braak et al. 2003).

Our observation that low doses of rotenone induce transcriptional changes selectively in DA neurons suggests that rotenone is a useful tool to identify neuron-specific responses to cellular stress. Indeed, our qPCR data from GABAergic neurons of the substantia nigra and striatum demonstrated that the transcriptional activation of Nmt2, Pex11a, and Txnip is specific for DA neurons in the SNC. Although we did not measure mitochondrial functions in the present study, these data are in agreement with previous reports about an increased susceptibility of DA neurons to rotenone induced complex I inhibition (Betarbet et al., 2000; Sherer et al., 2003b). However, the cumulative doses used by Betarbet and Sherer were substantially higher than the ones used in our experiments and caused highly variable effects between animals. This is reflected in large differences of the nigrostriatal defects in the striatum (Betarbet et al., 2000; Sherer et al., 2003b; Höglinger et al., 2003; Lapointe et al., 2004, Zhu et al., 2004) as well as a lack of cellular specificity in some experiments (Höglinger et al., 2003; Lapointe et al., 2004, Zhu et al., 2004). One potential explanation might be the high level of systemic toxicity, indicated by mortality rates of 50% or more in most of these experiments that could mask the specific effects in the central nervous system. The considerably lower mortality rate in our model, only 1 out of 34 animals died, confirms the milder toxicity of our regimen, which may explain the specificity of the transcriptional responses for DA neurons. It should be stressed, however, that a significant effect of rotenone on both weight loss and behavioral dysfunction was necessary to observe the reported changes in gene expression in DA neurons, indicating a threshold for the transcriptional effects of this mild rotenone treatment.

In summary our data demonstrate that low dose rotenone treatment of rats causes transcriptional alterations in several cell death related pathways that are specific for DA neurons in the SNC. The increasing knowledge about cell-type specific responses to disease relevant perturbations might eventually result in protective therapeutic strategies designed to halt the progression of the degenerative process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Lee Goodglick for providing access to the Arcturus PixCell II laser-capture microscope and Desmond Smith for usage of his ABI 7900HT sequence detection system.

Funding:

The work was supported by US Army MRMC contract DAMD17-94-C-4069 and Public Health Service awards U54 ES12078 and P50 NS38367.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alam M, Schmidt WJ. Rotenone destroys dopaminergic neurons and induces parkinsonian symptoms in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2002;136(1):317–324. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A, Krishnan KJ, Morris CM, Taylor GA, Reeve AK, Perry RH, Jaros E, Hersheson JS, Betts J, Klopstock T, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. High levels of mitochondrial DNA deletions in substantia nigra neurons in aging and Parkinson disease. Nat. Genet. 2006;38(5):515–517. doi: 10.1038/ng1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3(12):1301–1306. doi: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventure P, Guo H, Tian B, Liu X, Bittner A, Roland B, Salunga R, Ma XJ, Kamme F, Meurers B, Bakker M, Jurzak M, Leysen JE, Erlander MG. Nuclei and subnuclei gene expression profiling in mammalian brain. Brain Res. 2002;943(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02504-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Rüb U, Gai WP, Del Tredici K. Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: possible routes by which vulnerable neuronal types may be subject to neuroinvasion by an unknown pathogen. J Neural Transm. 2003;110(5):517–36. doi: 10.1007/s00702-002-0808-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breidert T, Callebert J, Heneka MT, Landreth G, Launay JM, Hirsch EC. Protective action of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist pioglitazone in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2002;2002;82(3):615–624. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri I, Keller-McGandy C, Bouzou B, Asteris G, Clark TW, Frosch MP, Standaert DG. Effects of gender on nigral gene expression and parkinson disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26(3):606–614. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Guzman JN, Ilijic E, Mercer JN, Rick C, Tkatch T, Meredith GE, Surmeier DJ. ‘Rejuvenation’ protects neurons in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2007;447(7148):1081–1086. doi: 10.1038/nature05865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JW, Jeon JH, Yoon SR, Choi I. Vitamin D3 upregulated protein 1 (VDUP1) is a regulator for redox signaling and stress-mediated diseases. J. Dermatol. 2006;33(10):662–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran B, Gherbesi N, Hendricks G, Flavell RA, Davis RJ, Gangwani L. Deficiency of the zinc finger protein ZPR1 causes neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(19):7471–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602057103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducker CE, Upson JJ, French KJ, Smith CD. Two N-myristoyltransferase isozymes play unique roles in protein myristoylation, proliferation, and apoptosis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2005;3(8):463–476. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury MS, Ito H, Zinner MJ, Ashley SW, Whang EE. RNA interference targeting the M2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase enhances pancreatic adenocarcinoma chemosensitivity to gemcitabine. Oncogene. 2004;23(8):1539–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. Empirical bayes methods and false discovery rates for microarrays. Genet. Epidemiol. 2002;23(1):70–86. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan GC, Chu G, Mitton B, Song Q, Yuan Q, Kranias EG. Small heat-shock protein Hsp20 phosphorylation inhibits beta-agonist-induced cardiac apoptosis. Circ Res. 2004;94(11):1474–82. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129179.66631.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114(5):2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming SM, Zhu C, Fernagut PO, Mehta A, DiCarlo CD, Seaman RL, Chesselet MF. Behavioral and immunohistochemical effects of chronic intravenous and subcutaneous infusions of varying doses of rotenone. Exp. Neurol. 2004;187(2):418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuenzalida K, Quintanilla R, Ramos P, Piderit D, Fuentealba RA, Martinez G, Inestrosa NC, Bronfman M. Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor {gamma} Up-regulates the Bcl-2 Anti-apoptotic Protein in Neurons and Induces Mitochondrial Stabilization and Protection against Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282(51):37006–37015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiana E, Vernier P, Dupont E, Evrard C, Rouget P. Identification of a neural-specific cDNA, NPDC-1, able to down-regulate cell proliferation and to suppress transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(5):1560–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünblatt E, Mandel S, Maor G, Youdim MB. Gene expression analysis in N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mice model of Parkinson’s disease using cDNA microarray: effect of R-apomorphine. J. Neurochem. 2001;78(1):1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünblatt E, Mandel S, Jacob-Hirsch J, Zeligson S, Amariglo N, Rechavi G, Li J, Ravid R, Roggendorf W, Riederer P, Youdim MB. Gene expression profiling of parkinsonian substantia nigra pars compacta; alterations in ubiquitin-proteasome, heat shock protein, iron and oxidative stress regulated proteins, cell adhesion/cellular matrix and vesicle trafficking genes. J. Neural Transm. 2004;111(12):1543–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu G, Deutch AY, Franklin J, Levy S, Wallace DC, Zhang J. Profiling genes related to mitochondrial function in mice treated with N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;308(1):197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarsund M, Lerner M, Zhu C, Merup M, Jansson M, Gahrton G, Kluin-Nelemans H, Einhorn S, Grandér D, Sangfelt O, Corcoran M. Disruption of a novel ectodermal neural cortex 1 antisense gene, ENC-1AS and identification of ENC-1 overexpression in hairy cell leukemia. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(23):2925–36. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E, Graybiel AM, Agid YA. Melanized dopaminergic neurons are differentially susceptible to degeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 1988;334(6180):345–348. doi: 10.1038/334345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höglinger GU, Feger J, Prigent A, Michel PP, Parain K, Champy P, Ruberg M, Oertel WH, Hirsch EC. Chronic systemic complex I inhibition induces a hypokinetic multisystem degeneration in rats. J Neurochem. 2003;84(3):491–502. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joguchi A, Otsuka I, Minagawa S, Suzuki T, Fujii M, Ayusawa D. Overexpression of VDUP1 mRNA sensitizes HeLa cells to paraquat. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;293(1):293–297. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junn E, Han SH, Im JY, Yang Y, Cho EW, Um HD, Kim DK, Lee KW, Han PL, Rhee SG, Choi I. Vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1 mediates oxidative stress via suppressing the thioredoxin function. J Immunol. 2000;164(12):6287–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamme F, Zhu J, Luo L, Yu J, Tran DT, Meurers B, Bittner A, Westlund K, Carlton S, Wan J. Single-cell laser-capture microdissection and RNA amplification. Methods Mol. Med. 2004;99:215–23. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-770-X:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama Y, Sakai A, Oue N, Asaoku H, Otsuki T, Shiomomura T, Masuda R, Hino N, Takimoto Y, Imanaka F, Yasui W, Kimura A. A possible role for the loss of CD27-CD70 interaction in myelomagenesis. Br J Haematol. 2003;120(2):223–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolluri SK, Balduf C, Hofmann M, Göttlicher M. Novel target genes of the Ah (dioxin) receptor: transcriptional induction of N-myristoyltransferase 2. Cancer Res. 2001;61(23):8534–8539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe N, St-Hilaire M, Martinoli MG, Blanchet J, Gould P, Rouillard C, Cicchetti F. Rotenone induces non-specific central nervous system and systemic toxicity. FASEB J. 2004;18(6):717–719. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0677fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, David C, Kikuta T, Somogyvari-Vigh A, Arimura A. Signaling cascades involved in neuroprotection by subpicomolar pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide 38. J Mol Neurosci. 2005;27(1):91–105. doi: 10.1385/JMN:27:1:091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Baumgart E, Dong GX, Morrell JC, Jimenez-Sanchez G, Valle D, Smith KD, Gould SJ. PEX11alpha is required for peroxisome proliferation in response to 4-phenylbutyrate but is dispensable for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-mediated peroxisome proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22(23):8226–8240. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.23.8226-8240.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss B, Haeckel O, Wildmann J, Miki T, Seino S, Roeper J. K-ATP channels promote the differential degeneration of dopaminergic midbrain neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8(12):1742–1751. doi: 10.1038/nn1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Selvakumar P, Ali K, Shrivastav A, Bajaj G, Resch L, Griebel R, Fourney D, Meguro K, Sharma RK. Expression of N-myristoyltransferase in human brain tumors. Neurochem. Res. 2005;30(1):9–13. doi: 10.1007/s11064-004-9680-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann VM, Cooper JM, Krige D, Daniel SE, Schapira AH, Marsden CD. Brain, skeletal muscle and platelet homogenate mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1992;115(2):333–342. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RM, Callahan LM, Casaceli C, Chen L, Kiser GL, Chui B, Kaysser-Kranich TM, Sendera TJ, Palaniappan C, Federoff HJ. Dysregulation of gene expression in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-lesioned mouse substantia nigra. J. Neurosci. 2004;24(34):7445–7454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4204-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RM, Kiser GL, Kaysser-Kranich TM, Lockner RJ, Palaniappan C, Federoff HJ. Robust dysregulation of gene expression in substantia nigra and striatum in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006;21(2):305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minn AH, Hafele C, Shalev A. Thioredoxin-interacting protein is stimulated by glucose through a carbohydrate response element and induces beta-cell apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2005;146(5):2397–2405. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MR, Gentle D, Abdulrahman M, Maina EN, Gupta K, Banks RE, Wiesener MS, Kishida T, Yao M, The B, Lati F, Maher ER. Tumor suppressor activity and epigenetic inactivation of hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitor type 2/SPINT2 in papillary and clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65(11):4598–606. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishinaka Y, Nishiyama A, Masutani H, Oka S, Ahsan KM, Nakayama Y, Ishii Y, Nakamura H, Maeda M, Yodoi J. Loss of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1 in human T-cell leukemia virus type I-dependent T-cell transformation: implications for adult T-cell leukemia leukemogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64(4):1287–1292. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama A, Matsui M, Iwata S, Hirota K, Masutani H, Nakamura H, Takagi Y, Sono H, Gon Y, Yodoi J. Identification of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D(3) up-regulated protein 1 as a negative regulator of thioredoxin function and expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274(31):21645–21650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh-hashi K, Naruse Y, Amaya F, Shimosato G, Tanaka M. Cloning and characterization of a novel GRP78-binding protein in the rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(12):10531–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S, Lai EW, Pang AL, Brouwers FM, Chan WY, Eisenhofer G, de Krijger R, Ksinantova L, Breza J, Blazicek P, Kvetnansky R, Wesley RA, Pacak K. Downregulation of metastasis suppressor genes in malignant pheochromocytoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2005;114(1):139–143. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. A model for p53-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1997;389(6648):300–5. doi: 10.1038/38525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Hosoi T, Okuma Y, Kaneko M, Nomura Y. Sodium 4-phenylbutyrate protects against cerebral ischemic injury. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;66(4):899–908. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.001339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RA. Non-genotoxic hepatocarcinogenesis: suppression of apoptosis by peroxisome proliferators. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1996;804:588–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb18647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu EJ, Angelastro JM, Greene LA. Analysis of gene expression changes in a cellular model of Parkinson disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004;18(1):54–74. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Itoh K, Higashitsuji H, Nonoguchi K, Liu Y, Watanabe H, Nakano T, Fukumoto M, Chiba T, Fujita J. Cirp protects against tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis via activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763(3):290–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira AHV, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Jenner P, Clark JB, Marsden CD. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1989;333(8649):1269. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira AH, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Clark JB, Jenner P, Marsden CD. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 1990;54(3):823–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader M, Reuber BE, Morrell JC, Jimenez-Sanchez G, Obie C, Stroh TA, Valle D, Schroer TA, Gould SJ. Expression of PEX11beta mediates peroxisome proliferation in the absence of extracellular stimuli. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273(45):29607–29614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader M, Fahimi HD. Peroxisomes and oxidative stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1763(12):1755–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze PC, Yoshioka J, Takahashi T, He Z, King GL, Lee RT. Hyperglycemia promotes oxidative stress through inhibition of thioredoxin function by thioredoxin-interacting protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(29):30369–30374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvakumar P, Smith-Windsor E, Bonham K, Sharma RK. N-myristoyltransferase 2 expression in human colon cancer: cross-talk between the calpain and caspase system. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(8):2021–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvakumar P, Lakshmikuttyamma A, Charavaryamath C, Singh B, Tuchek J, Sharma RK. Expression of myristoyltransferase and its interacting proteins in epilepsy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;335(4):1132–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvakumar P, Sharma RK. Role of calpain and caspase system in the regulation of N-myristoyltransferase in human colon cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19(5):823–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer TB, Betarbet R, Testa CM, Seo BB, Richardson JR, Kim JH, Miller GW, Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A, Greenamyre JT. Mechanisms of toxicity in rotenone models of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2003a;23(34):10756–10764. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10756.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer TB, Kim JH, Betarbet R, Greenamyre JT. Subcutaneous rotenone exposure causes highly selective dopaminergic degeneration and alpha-synuclein aggregation. Exp. Neurol. 2003b;179(1):9–16. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow RH, Parks JK, Miller SW, Tuttle JB, Trimmer PA, Sheehan JP, Bennett JP, Davis RE, Parker WD., Jr. Origin and functional consequences of the complex I defect in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1996;40(4):663–671. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi T, Kosaka J, Oshika T. JNK inhibitory kinase is up-regulated in retinal ganglion cells after axotomy and enhances BimEL expression level in neuronal cells. J Neurochem. 2005;95(2):526–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Irizarry RA, Gentleman R, Murillo FM, Spencer F. A model based background adjustment for oligonucleotide expression arrays. John Hopkins University, Department of Biostatistics; Baltimore, MD: 2003. Technical Report. Working Papers. [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, Zhou B, Liu X, Qiu W, Jin Z, Yen Y. Wild-type p53 regulates human ribonucleotide reductase by protein-protein interaction with p53R2 as well as hRRM2 subunits. Cancer Res. 2003;63(5):980–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yew EH, Cheung NS, Choy MS, Qi RZ, Lee AY, Peng ZF, Melendez AJ, Manikandan J, Koay ES, Chiu LL, N,g WL, Whiteman M, Kandiah J, Halliwell B. Proteasome inhibition by lactacystin in primary neuronal cells induces both potentially neuroprotective and pro-apoptotic transcriptional responses: a microarray analysis. J. Neurochem. 2005;94(4):943–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Nakamura H, Masutani H, Yodoi J. The involvement of thioredoxin and thioredoxin binding protein-2 on cellular proliferation and aging process. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1055:1–12. doi: 10.1196/annals.1323.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Vourc’h P, Fernagut PO, Fleming SM, Lacan S, Dicarlo CD, Seaman RL, Chesselet MF. Variable effects of chronic subcutaneous administration of rotenone on striatal histology. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;478(4):418–426. doi: 10.1002/cne.20305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.