Abstract

Dizygotic (DZ) twinning has a genetic component and is common among sub-Saharan Africans; in The Gambia its frequency is up to 3% of live births. Variation in Pentraxin 3 (PTX3), a soluble pattern recognition receptor that plays an important role both in humoral innate immunity and in female fertility, has been associated with resistance to M. tuberculosis infection and to P. aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis patients. We tested whether PTX3 variants in Gambian women associate with DZ twinning, by genotyping five PTX3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 130 sister pairs (96 full sibs and 34 half sibs) who had DZ twins. We found that two, three and five SNP haplotypes differed in frequency between twinning mothers and those without a history of twinning (from p = 0.006 to 3.03e-06 for two SNP and three SNP haplotypes, respectively). Twinning mothers and West African tuberculosis-controls from a previous study shared several frequent haplotypes. Most importantly, our data are consistent with the previously reported association of PTX3 and female fertility in a West African sample from Ghana. Taken together, these results indicate that selective pressure on PTX3 variants that affect the innate immune response to infectious agents, could also produce the observed high incidence of DZ twinning in Gambians.

Keywords: dizygotic twinning, fertility, innate immunity, Pentraxin 3, The Gambia, Africa

INTRODUCTION

It has been known for a long time that “with mankind a tendency to produce twins runs in families” (Darwin, 1871, citing Sedgwick, 1863) and there is evidence that familial dizygotic (DZ) twinning is at least, in part, genetically determined (Hoekstra et al., 2008; Parisi et al., 1983; Schmidt et al., 1983). Although the fundamental biological phenomenon in di- and multizygotic pregnancies is multiple ovulations, the underlying molecular basis of the trait is not understood.

In some areas of West Africa, the twinning frequency is three to four times the rate seen in Europeans, most notably in the Yoruba population of South-Western Nigeria. At 45.1 twin pairs per 1,000 births, the reported twinning rate in Yoruba is four times that of women in Europe and America (10/1,000) and more than nine times the twinning rate (5/1,000) of some Asian countries (Bowman, 1990; Hoekstra et al., 2008; Nylander, 1978). Trizygotic triplet pregnancies (1.6/1,000) are 16 times more common in the Yoruba than European or Asian populations (Nylander, 1978; Nylander, 1969; Nylander, 1971; Pison, 1992; Vogel & Motulsky, 1997). A recent report has supported the notion that twinning is more common throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa than the rest of the world. However, the actual rates are somewhat lower than previous reports, and Benin, not Nigeria, is argued to have the highest frequency (Smits & Monden, 2011). It is not known why DZ twinning is so common in Africa, although some have suggested that the high frequency of twinning/multiple ovulation in West Africans has been the result of a selective reproductive advantage for twinning mothers compared to mothers of singletons (Sear et al., 2001). Whether twinning confers a selective advantage in human populations, however, may also be related to the level of resources in a given location and time (Helle et al., 2004; Lummaa et al., 1998); in resource limited environments twinning is associated with an overall decrease in reproductive fitness (Helle et al., 2004; Lummaa et al., 1998). Additionally, in some West-African countries (e.g. Guinea-Bissau) it has been shown that twins are breastfed 6 months longer than singletons, potentially limiting the number of pregnancies (P. Aaby, personal communication). More importantly, the risk of maternal mortality is 3 to 5 times higher in twin pregnancies and infant mortality is higher in twins than singletons (Hoj et al., 2002), so it is far from obvious that twinning itself represents a reproductive or fitness advantage in sub-Saharan Africa, where resources are often limited.

In order to identify a DZ twinning predisposing locus, we recruited sisters who had DZ twins from the Gambia, hence enriching for putative genetic factors. The Gambia is a unique country for studying the genetics of dizygotic twinning in West Africa because of a very high twinning rate ranging from ~ 1.5 % to ~ 3% of which more than 75% are DZ twins (Jaffar et al., 1998; Sear et al., 2000; Sirugo et al., in preparation). Moreover, there is no reported significant use of fertility drugs or consumption of phytoestrogen-containing foods, minimizing the effects of known environmental agents that increase twinning frequency (Newman & Luke, 2000).

In our study we tested for association between SNPs in the Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) gene and DZ twinning. The PTX3 gene maps on chromosome 3q25 (MIM ID 602492) and belongs to the Pentraxin superfamily that is highly evolutionarily conserved. The superfamily members are divided into Long and Short Pentraxins, where C-Reactive Protein (CRP) and serum amyloid (SAP) are Short Pentraxins produced in the liver and PTX3 is an example of a Long Pentraxin. Pentraxin 3, as other Long Pentraxins (PTX4, NP1, NP2 and NPR) is characterized by a 174 amino acid-long amino-terminal domain and it is expressed on dendritic cells as well as macrophages, following Toll-Like Receptor activation and inflammatory cytokine production (e.g. IL-1, TNF-α). The receptor directly binds a number of infectious organisms, ranging from fungi to bacteria, activates complement, and facilitates phagocytes, making PTX3 an important mediator of the innate immunity response (for a comprehensive review see: Bottazzi et al., 2009; Garlanda et al., 2005; Mantovani et al., 2008). Of significance to our study, PTX3 also has an important role in female fertility, i.e. in the delivery of the cumulus oophorus-oocyte complex to the oviduct as well as in determining successful fertilization (Varani et al., 2002). Because of its dual role PTX3 is an excellent candidate gene for DZ twinning in a West African setting, where there exists a high prevalence of morbidity and mortality due to infection (e.g. malaria, tuberculosis, pneumococcal disease). We hypothesize that variations in PTX3 could have been under positive selection for protection from infectious diseases (Chiarini et al., 2010; Olesen et al., 2007) but SNPs or haplotypes that confer a selective advantage due to protection from infection could also have a pleiotropic effect on fertility, partially contributing to the unusually high frequency of DZ twinning in The Gambia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this report, we present information on a sample of 130 affected sister pairs each of whom had DZ twins and 95 healthy Gambian control women with no evidence of twin deliveries. With the exception of 5 sets of twins who were of the same sex and for which we determined zygosity by genotyping SNPs from unrelated autosomal loci, all the twin sets in the sample were of different sex. In total, we recruited 195 women from 92 families for a total of 130 sibpairs, 96 of whom were full sisters and 34 were half-sisters. The pairs were recruited from across The Gambia and their age, family relationships, parity, food consumption habits and ethnicity (traced back to the grandparents) were assessed using a specific study questionnaire. Unrelated controls were recruited from the same sites and matched for ethnicity. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The study was approved by the combined Gambia Government/MRC National Ethics Committee of The Gambia.

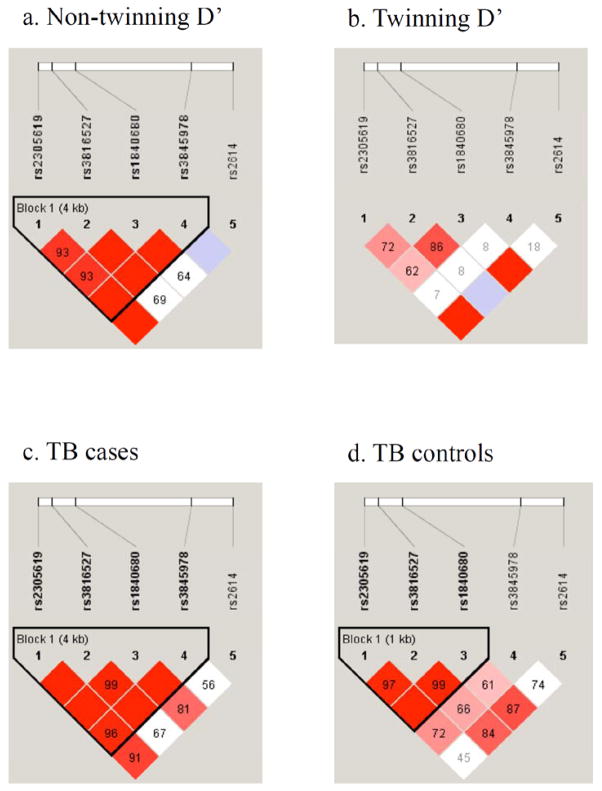

PTX3 genotypes for 5 intragenic SNPs (TaqMan assay, ABI) were determined in genomic DNA samples, obtained with standard salting out method. SNPs were the same as reported in Olesen et al., (2007). Marker positions, heterozygosities and allele frequencies are shown in Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1. PTX3 gene structure.

Gene map with 3′ UTR region, exons and introns. SNPs position and inter-marker distances are indicated.

Table 1.

Gene and SNP information

| Gene and Chromosome | SNP | Position | Role | Amino Acid Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pentraxin 3 Chromosome 3 |

rs2305619 | 158637555 | Intron 1 (boundary) | - |

| rs3816527 | 158638008 | Coding exon 2 | A/D | |

| rs1840680 | 158638723 | Intron 2 | - | |

| rs3845978 | 158642388 | Intron 2 | - | |

| rs2614 | 158643693 | 3′ UTR | - |

Table 2.

Case-control single locus association based on case resampling

| SNP | Allele | Allele Freq. | HWE p-value | Case v Control p-value Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mean (SD) Case | Control | Mean (SD) Case | Control | Allele | Genotype | ||

| rs2305619 | C | 0.45(0.02) | 0.44 | 0.70 (0.25) | 0.53 | 0.79 (0.18) | 0.72 (0.19) |

| rs3816527 | C | 0.25(0.02) | 0.28 | 0.67 (0.28) | 1.00 | 0.57 (0.22) | 0.71 (0.19) |

| rs1840680 | T | 0.30(0.02) | 0.29 | 0.56 (0.30) | 0.46 | 0.78 (0.18) | 0.50 (0.22) |

| rs3845978 | T | 0.25(0.02) | 0.24 | 0.53 (0.30) | 0.39 | 0.72 (0.21) | 0.81 (0.16) |

| rs2614 | T | 0.12(0.01) | 0.11 | 0.72 (0.28) | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.19) | 0.78 (0.21) |

We performed a case-control analysis by selecting one twinning sister from each family as a case (92 total cases per analysis). To insure that our results were not biased by the “case” selection process we repeated this random selection 1,000 times. The 1,000 case datasets were compared to the same controls, and all analyses were repeated 1,000 times. Single site allele frequency, genotype frequency, and Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) analyses were performed using PLINK and the means and standard deviations for the results are presented (Purcell et al., 2007). Statistical significance was determined using chi square tests. An alternative analysis, GEE (Generalized Estimating Equations), that had the capacity to adjust for relatedness was also performed in which we included all twinning mothers from a family in order to test whether our sampling biased the association findings (Hancock et al., 2007). STATA 11.0 statistical software (College Station, TX) was used for this analysis.

Haplotype analyses to test for linkage disequilibrium and to determine haplotype frequencies were performed using Powermarker on the 100 randomly selected case sets and controls (Liu & Muse, 2005). The Powermarker haplotype trend analysis was performed. Powermarker uses an EM algorithm to determine haplotype frequency distributions when phase is unknown. This was run both using a sliding window of 2–3 SNPs, as well as the complete set of 5 SNPs. This analysis is a regression approach to test haplotype-trait association for a dichotomous or continuous trait. The test for association then uses an F test for a specialized additive model.

An alternative haplotype analysis method CCREL version 3.0 (Browning et al., 2005) was also employed because CCREL is optimized for haplotype association testing in study designs containing related cases and unrelated controls with haplotype phase unknown. Therefore, CCREL was able to be run using the full dataset (n = 195 cases, 95 controls). CCREL was used to perform 2–3 locus sliding window haplotype analysis as well as single locus genotypic association tests; 4–5 SNP haplotypes were not assessed because of potentially increased Type 1 error beyond 3 SNP haplotypes. CCREL accounts for the correlations between related case individuals due to IBD sharing by calculating an optimal “weight” for each individual based on their unique IBD sharing probability. These “weights” are then utilized to construct a composite likelihood which is then maximized iteratively to form likelihood ratio tests for haplotype and single-marker association testing. The likelihood ratio test is asymptotically equivalent to a chi-square test of association using the aforementioned “weighted” counts of each haplotype/allele in cases and controls. To reduce the degrees of freedom of the likelihood ratio tests, and to optimize the overall efficiency of the test, rare haplotypes defined as having ten or fewer expected observations were pooled together with the next larger haplotype group by using the combined threshold = 10 option. Previous studies, on both actual and simulated data, show that CCREL is more powerful than currently employed methods that employ chi-square testing after selecting one member of each pedigree (Browning et al 2005). We also used CCREL to assess single SNP associations in our data.

Pairwise LD was characterized and standard summary statistics D′ were calculated using HaploView statistical software (Barrett et al., 2005; Devlin & Risch, 1995).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

No single SNP associations were found between DZ and PTX3, and results across analytical methods were highly consistent (Tables 2 and 3),. However, both the sliding window haplotype and the entire 5 SNPs-haplotype analyses demonstrated significant association with PTX3 using the resampling analyses (Table 4). Of note, the analyses using related cases provided significant evidence for a haplotype effect with the same 3 SNP haplotype (rs3816527-rs1840680-rs3845978) as the resampling method with p at the 10−6 level (Table 4). The two SNP haplotype, rs3816527-rs1840680, was also significant using CCREL (p = 0.012) and almost significant using our resampling method (p= 0.07).

Table 3.

Analyses of twinning mothers including related cases using GGE and CCREL

| SNP | 95% CI | P-value1 | P-value2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | Lower | Upper | |||

| rs2305619 | 1.02 | 0.69 | 1.49 | 0.930 | 0.970 |

| rs3816527 | 0.85 | 0.55 | 1.31 | 0.465 | 0.478 |

| rs1840680 | 1.06 | 0.71 | 1.59 | 0.770 | 0.746 |

| rs3845978 | 1.11 | 0.74 | 1.68 | 0.608 | 0.608 |

| rs2614 | 1.09 | 0.58 | 2.02 | 0.795 | 0.708 |

P-values from single marker genotypic test of association using GEE

P-values from single marker genotypic test of association in CCREL v 3.0

Table 4.

Haplotype sliding window association

| Haplotype | Mean p-value (SD)1 | LR p-value2 |

|---|---|---|

| rs2305619-rs3816527 | 0.69 (0.17) | 0.577 |

| rs3816527-rs1840680 | 0.07 (0.07) | 0.012 |

| rs1840680-rs3845978 | 0.22 (0.14) | 0.006 |

| rs3845978-rs2614 | 0.76 (0.16) | 0.53 |

| rs2305619-rs3816527-rs1840680 | 0.20 (0.14) | 2.42e-03 |

| rs3816527-rs1840680-rs3845978 | 0.04 (0.04) | 3.03e-06 |

| rs1840680-rs3845978-rs2614 | 0.23 (0.13) | 7.12e-04 |

| rs2305619-rs3816527-rs1840680-rs3845978-rs2614 | 0.05 (0.06) | N/A |

In bold are statistically significant p values (p≤0.05)

P-values based on 1000 random samples from the case families. Standard deviation of p values are in parantheses

P-values are from CCREL weighted likelihood ratio haplotype tests, combined threshold = 10; N/A: not applicable due to method instability (see main text)

Our study provides strong evidence indicating that PTX3 variation has a significant association with DZ twinning in The Gambia. It is well known that PTX3 is a physiological downstream target of GDF9 (Varani et al., 2002) and GDF9 mutations have been associated with both DZ twinning and increased ovulation rate (Montgomery et al., 2004; Palmer et al., 2006). PTX3 expression and secretion in the peri-ovulatory cumulus oophorus has a key function in the assembly of the hyaluronic-rich extra-cellular matrix, known to facilitate fertilization (Russell & Salustri, 2006). However in our sample twinning associates with PTX3 genetic variation per se, that is regardless of any trans-acting control, such as GDF9, that could also contribute to the twinning phenotype. Overall, our results support the conclusion that PTX3 haplotypes associate with DZ twinning. The strength of our conclusion is based not only on our own findings as reported here, but on prior observations previously published, associating PTX3 variants with protection from pulmonary TB in Guinea-Bissau (Olesen et al., 2007). This report and our current study taken together provide statistical and biological evidence that this gene and in particular specific haplotypes affect both traits, providing a more compelling biological explanation for both data sets.

Further biological evidence of the role of PTX3 in reproduction is supported by a mouse model, where matrix-embedded PTX3 can direct and facilitate entrapment of spermatozoa and hence the fertilization of eggs (Salustri et al., 2004). The interplay between innate immunity and fertility could result in PTX3 variants simultaneously playing a role in resistance against pathogens as well as in self/non self discrimination editing (Rovere et al., 2000; van Rossum et al., 2004). The PTX3 role in twinning could be indirect, via elimination of cellular debris from luteal cells apoptosis, consequently altering steroidogenesis and ovulation (Pate & Landis, 2001) or in abating inflammatory responses generated by dead and dying luteal cells and preserving ovarian tissues from damage. Activated innate immunity pathways modulate tissue wasting and preservation of integrity by sterile inflammation; in the ovary tissue damage and remodelling take place in a controlled fashion and innate immunity seems to play a key role in modulating the overall process (Spanel-Borowski, 2011). In this light, ovulation can be thought as an inflammation-like process in which PTX3 (produced by cumulus oophorus cells and localized within the cumulus matrix) is a main player (Moalli et al., 2011), a concept supported by the finding that Ptx3−/− mice, generated by homologous recombination, are severely sub-fertile (Moalli et al., 2011; Varani et al., 2002). Thus variation in the PTX3 gene may operate at the level of ovulation and fertilization to influence the risk of DZ twinning.

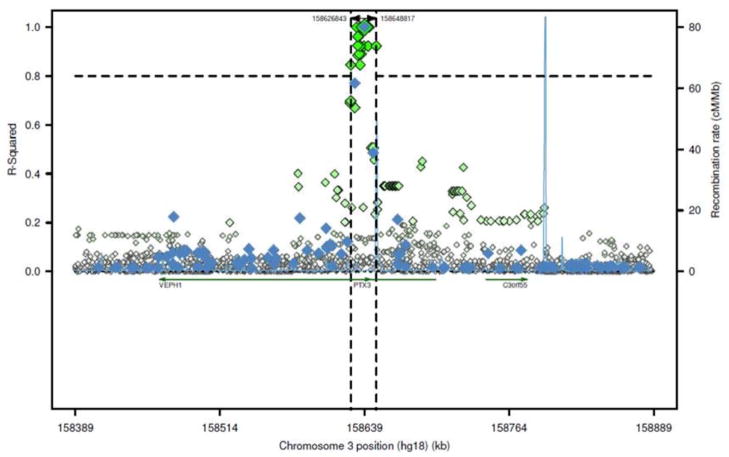

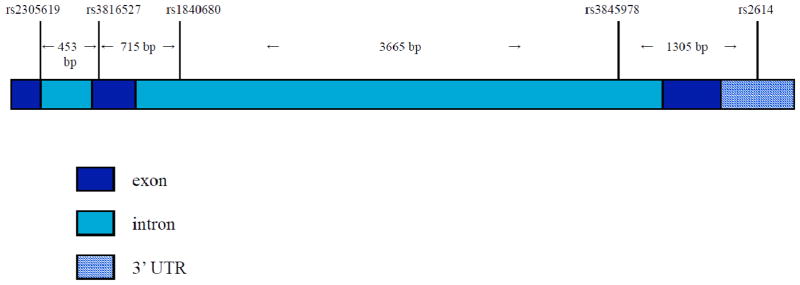

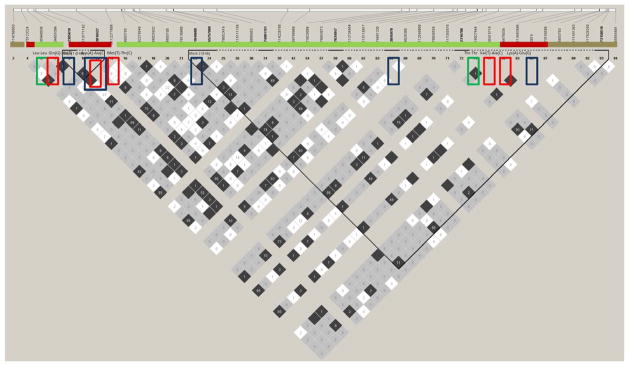

A direct, independent effect of the same PTX3 mutations, on both immune responses to pathogens and multiple ovulations can be postulated, that is a pleiotropy model where DZ twinning would occur in parallel with and independently from immunological pathways because of the PTX3 function on both innate defenses and on fertility. Specifically, the haplotypes that are more common in Bissau TB cases showed a trend to be more common in Gambian non twinning mothers (e.g., A-C-A-C-C, 0.24 in TB cases and 0.25 in non twinning mothers compared to 0.18 in TB controls and 0.19 in twinning cases) and those more common in TB controls are also more common in DZ twinning mothers compared to TB cases and non-twinning mothers (e.g., G-A-G-C-C, 0.22 in TB controls and 0.28 twinning cases compared to 0.17 and 0.24 in TB cases and non-twinning mothers) (Table 5). Interestingly, the very similar “protective” PTX3 haplotypes, observed in Bissau TB controls and in Gambian twinning mothers suggests that the effect is common across West Africans that belong to different ethnic groups. Further strengthening this argument is the observed LD pattern in the TB cases, which is almost identical to that in our non-twinning mothers (Figure 2a–d), indicating that they are tagging a variant(s) common to both populations that affect both phenotypes or act pleiotropically. Additional support for this conclusion comes from a study investigating the effect of PTX3 genetic variants on fertility in a female Ghanaian population sample that identified an association in the gene region encompassing SNPs rs2305619-rs3816527-rs1840680, corroborating the notion that PTX3 affects reproductive characteristics in West Africans (May et al., 2010). Finally, this hypothesis is further reinforced by another study in which the same haplotype that associates with protection from TB in Bissau has been shown to associate with protection from P. aeruginosa airway infection in European patients with CF (Chiarini et al., 2010). We would argue that it is highly unlikely to have observed this recurrent haplotype pattern associating with different, but innate immune-response related, phenotypes by chance alone because combining the probabilities from these independent studies yields an overwhelmingly significant result (≪ 0.05). LD analyses (Figure 3) of rs1840680 and adjacent SNPs data from a GWAS of tuberculosis in Gambians (data of the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, www.wtccc.org.uk, Thye et al., 2010) and from the 1,000 genomes project study of Yoruba trios from Nigeria, show significant LD encompassing PTX3 and extending on both sides of the gene (up to 125kb at 3′ end of the gene). This pattern is consistent with neutral variants hitchhiking with one or more beneficial PTX3 mutations on limited length haplotypes resulting from a combination of selection pressure and recombination rate, i.e. a selective sweep across PTX3. Lastly, the region encompassed by the SNPs we genotyped includes five previously defined missense mutations (Figure 4). One of these was genotyped by us (rs3816527), but it is not in LD with any of the other four SNPs in the Yoruba HapMap samples. Although PolyPhen-2 predicts that this is a benign mutation with respect to protein structure and function (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/; Adzhubei et al., 2010), we cannot rule out the possibility that there is another effect such as mRNA stability differences, which is captured by the haplotype that associates with twinning.

Table 5.

Haplotype frequencies and association for five marker haplotypes and comparison to tuberculosis study haplotype distributions

| Haplotype rs2305619-rs3816527-rs1840680-rs3845978-rs2614 |

Haplotype Freq. | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case Mean (SD) | Controls | P-value | |

| A-C-A-T-C | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.01 | 0.03 (0.03) |

| A-A-G-C-T | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.10 | 0.70 (0.21) |

| G-A-G-T-C | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.21 | 0.11 (0.08) |

| A-A-G-C-C | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.17 | 0.68 (0.21) |

| A-C-A-C-C | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.25 | 0.15 (0.12) |

| G-A-G-C-C | 0.28 (0.02) | 0.24 | 0.32 (0.21) |

| Haplotype rs2305619-rs3816527-rs1840680-rs3845978-rs2614 |

Haplotype Freq. | Haplotype Freq TB study | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Mean (SD) | Controls | Controls | Cases | |

| A-C-A-T-C | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.01 | NA | NA |

| A-A-G-C-T | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| G-A-G-T-C | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| A-A-G-C-C | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.26 |

| A-C-A-C-C | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.24 |

| G-A-G-C-C | 0.28 (0.02) | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.17 |

In bold are statistically significant p values (p≤0.05)

Figure 2. DZ twinning and non-twinning PTX3 LD structures.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) structures for pairwise D′ between markers characterizing haplotype blocks in PTX3 in non-twinning (Figure 2a), twinning (Figure 2b), TB cases (Figure 2c), and TB controls (Figure 2d). All figures are oriented 5′ to 3′, left to right. D′ values are indicated in percentages within squares in the LD plot. Strong LD is indicated by dark red, while light pink and white indicate uninformative and low confidence values, respectively. LD Blocks were created with the default algorithm in HaploView program (version 4.1) that creates 95% confidence bounds on D′ considered being in strong LD where 95% of the comparisons made are informative.

Figure 3. PTX3 linkage disequilibrium in African populations.

The advent of large scale genetic variant analysis allows for the fine scale calculation of r2 in multiple populations. This figure shows a) in blue the r2 relationship between rs1840680 and adjacent variants within the genome-wide association study of tuberculosis within Gambians as part of the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (www.wtccc.org.uk). In addition, b) in green, all variants found within the 1,000 genomes project study of Yoruba trios from Nigeria and the r2 relationship with rs1840680, with the dotted vertical lines representing the core region of LD with variants of r2 > 0.80. Plot provided with the assistance of code from Paul de Bakker (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap/).

Figure 4. PTX3 region LD structure of the Yoruba HapMap samples.

Linkage disequilibrium structure for pairwise r2 between markers characterizing haplotype blocks in PTX3 region encompassed by the SNPs we genotyped (in the blue boxes). The figure is oriented 5′ to 3′, left to right. Strong LD is indicated by dark gray, while light gray and white indicate uninformative and low confidence values, respectively; r2 (shades of black) is indicated in percentages within squares in the LD plots, with solid blocks without numbers indicating r2 = 1. Green and red boxes around markers indicate synonymous and missense mutations respectively. LD blocks were created with the default algorithm in HaploView program, version 4.1.

These results, taken together, support the hypothesis that PTX3 variants confer resistance to infections. In The Gambia this protective effect could partly explain the unusual frequency of DZ twinning, via an indirect selection mechanism. That is, whatever the biological mechanism involved, in Gambians (and possibly West Africans at large) DZ twinning could simply be a by-product of gene-variants (in this case PTX3 alleles) selected primarily for protection from infectious diseases. This model, in which DZ twinning is a simple consequence of selection on another complex trait (“susceptibility to infection”), might, if confirmed, represent a paradigm for the relationships between immunity-related genes that can be under intense selective pressure in the human genome and multiple other seemingly unrelated phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the participation of the many Gambian families who made this study possible. We would like to thank Dr Luca Lavra at Ospedale San Pietro FBF (Rome, Italy) for his helpful assistance during editing. Grant support: IP was supported by NIH grant 2T32HL007751-16A2; the twinning study in The Gambia was supported by the Medical Research Council (UK) award G0000690 to GS.

References

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottazzi B, Garlanda C, Cotena A, Moalli F, Jaillon S, Deban L, Mantovani A. The long pentraxin PTX3 as a prototypic humoral pattern recognition receptor: interplay with cellular innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman JE. Genetic variation and disorders in peoples of African origin. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Browning SR, Briley JD, Briley LP, Chandra G, Charnecki JH, Ehm MG, Johansson KA, Jones BJ, Karter AJ, Yarnall DP, Wagner MJ. Case-control single-marker and haplotypic association analysis of pedigree data. Genetic Epidemiology. 2005;28:110–122. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini M, Sabelli C, Melotti P, Garlanda C, Savoldi G, Mazza C, Padoan R, Plebani A, Mantovani A, Notarangelo LD, Assael BM, Badolato R. PTX3 genetic variations affect the risk of Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway colonization in cystic fibrosis patients. Genes Immun. 2010;11:665–670. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin CR. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. 1. Vol. 1. London: J. Murray; 1871. ( http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?viewtype=side&itemID=F955&pageseq=68) [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B, Risch N. A comparison of linkage disequilibrium measures for fine-scale mapping. Genomics. 1995;29:311–322. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlanda C, Bottazzi B, Bastone A, Mantovani A. Pentraxins at the crossroads between innate immunity, inflammation, matrix deposition, and female fertility. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:337–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock DB, Martin ER, Li YJ, Scott WK. Methods for interaction analyses using family-based case-control data: conditional logistic regression versus generalized estimating equations. Genet Epidemiol. 2007;31:883–893. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helle S, Lummaa V, Jokela J. Selection for increased brood size in historical human populations. Evolution. 2004;58:430–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra C, Zhao ZZ, Lambalk CB, Willemsen G, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, Montgomery GW. Dizygotic twinning. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:37–47. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoj L, da Silva D, Hedegaard K, Sandstrom A, Aaby P. Factors associated with maternal mortality in rural Guinea-Bissau. A longitudinal population-based study. BJOG. 2002;109:792–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffar S, Jepson A, Leach A, Greenwood A, Whittle H, Greenwood B. Causes of mortality in twins in a rural region of The Gambia, West Africa. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1998;18:231–238. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1998.11747952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Muse SV. PowerMarker: an integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2128–2129. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lummaa V, Haukioja E, Lemmetyinen R, Pikkola M. Natural selection on human twinning. Nature. 1998;394:533–534. doi: 10.1038/28977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Garlanda C, Doni A, Bottazzi B. Pentraxins in innate immunity: from C-reactive protein to the long pentraxin PTX3. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May L, Kuningas M, van Bodegom D, Meij HJ, Frolich M, Slagboom PE, Mantovani A, Westendorp RG. Genetic variation in pentraxin (PTX) 3 gene associates with PTX3 production and fertility in women. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:299–304. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.079111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moalli F, Jaillon S, Inforzato A, Sironi M, Bottazzi B, Mantovani A, Garlanda C. Pathogen Recognition by the Long Pentraxin PTX3. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:830421. doi: 10.1155/2011/830421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GW, Zhao ZZ, Marsh AJ, Mayne R, Treloar SA, James M, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, Duffy DL. A deletion mutation in GDF9 in sisters with spontaneous DZ twins. Twin Res. 2004;7:548–555. doi: 10.1375/1369052042663823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman RB, Luke B. Multifetal Pregancy, A handbook for care of the pregnant patient. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nylander PP. Causes of high twinning frequencies in Nigeria. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1978;24(Pt B):35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylander PP. The frequency of twinning in a rural community in Western Nigeria. Ann Hum Genet. 1969;33:41–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1969.tb01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylander PP. Ethnic differences in twinning rates in Nigeria. J Biosoc Sci. 1971;3:151–157. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000007896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen R, Wejse C, Vele DR, Bisseye C, Sodemann M, Aaby P, Rabna P, Worwui A, Chapman H, Diatta M, Adegbola RA, Hill PC, Ostergaard L, Williams SM, Sirugo G. DC-SIGN (CD209), pentraxin 3 and vitamin D receptor gene variants associate with pulmonary tuberculosis risk in West Africans. Genes Immun. 2007;8:456–467. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JS, Zhao ZZ, Hoekstra C, Hayward NK, Webb PM, Whiteman DC, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, Duffy DL, Montgomery GW. Novel variants in growth differentiation factor 9 in mothers of dizygotic twins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4713–4716. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi P, Gatti M, Prinzi G, Caperna G. Familial incidence of twinning. Nature. 1983;304:626–628. doi: 10.1038/304626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate JL, Landis KP. Immune cells in the corpus luteum: friends or foes? Reproduction. 2001;122:665–676. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pison G. Mortality and society in sub-Saharan Africa. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1992. Twins in sub-Saharan Africa: frequency, social status and mortality. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovere P, Peri G, Fazzini F, Bottazzi B, Doni A, Bondanza A, Zimmermann VS, Garlanda C, Fascio U, Sabbadini MG, Rugarli C, Mantovani A, Manfredi AA. The long pentraxin PTX3 binds to apoptotic cells and regulates their clearance by antigen-presenting dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;96:4300–4306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DL, Salustri A. Extracellular matrix of the cumulus-oocyte complex. Semin Reprod Med. 2006;24:217–227. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-948551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salustri A, Garlanda C, Hirsch E, De Acetis M, Maccagno A, Bottazzi B, Doni A, Bastone A, Mantovani G, Beck PP, Salvatori G, Mahoney DJ, Day AJ, Siracusa G, Romani L, Mantovani A. PTX3 plays a key role in the organization of the cumulus oophorus extracellular matrix and in in vivo fertilization. Development. 2004;131:1577–1586. doi: 10.1242/dev.01056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HD, Rosing FW, Schmidt DE. Causes of an extremely high local twinning rate. Ann Hum Biol. 1983;10:371–379. doi: 10.1080/03014468300006541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sear R, Mace R, McGregor IA. Maternal grandmothers improve nutritional status and survival of children in rural Gambia. Proc Biol Sci. 2000;267:1641–1647. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sear R, Shanley D, McGregor IA, Mace R. The fitness of twin mothers: evidence from rural Gambia. J Evol Biol. 2001;14:433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick A. British and Foreing Medico-Chirurg. Review. 1863 Jul;:170. [Google Scholar]

- Smits J, Monden C. Twinning across the Developing World. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanel-Borowski K. Ovulation as danger signaling event of innate immunity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;333:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thye T, Vannberg FO, Wong SH, Owusu-Dabo E, Osei I, Gyapong J, Sirugo G, Sisay-Joof F, Enimil A, Chinbuah MA, Floyd S, Warndorff DK, Sichali L, Malema S, Crampin AC, Ngwira B, Teo YY, Small K, Rockett K, Kwiatkowski D, Fine PE, Hill PC, Newport M, Lienhardt C, Adegbola RA, Corrah T, Ziegler A, Morris AP, Meyer CG, Horstmann RD, Hill AV. Genome-wide association analyses identifies a susceptibility locus for tuberculosis on chromosome 18q11.2. Nat Genet. 2010;42:739–741. doi: 10.1038/ng.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rossum AP, Fazzini F, Limburg PC, Manfredi AA, Rovere-Querini P, Mantovani A, Kallenberg CG. The prototypic tissue pentraxin PTX3, in contrast to the short pentraxin serum amyloid P, inhibits phagocytosis of late apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2667–2674. doi: 10.1002/art.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani S, Elvin JA, Yan C, DeMayo J, DeMayo FJ, Horton HF, Byrne MC, Matzuk MM. Knockout of pentraxin 3, a downstream target of growth differentiation factor-9, causes female subfertility. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1154–1167. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.6.0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel P, Motulsky A. Handbook of Human Genetics. Springer-Verlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]